A METHOD BASED ON THE ONTOLOGY OF LANGUAGE TO

SUPPORT CLUSTERS’ INTERPRETATION

Wagner Francisco Castilho

Federal Savings Bank and Catholic University of Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

Gentil José de Lucena Filho

Catholic University of Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

Hércules Antonio do Prado

Embrapa Food Technology and Catholic University of Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

Edilson Ferneda

Catholic University of Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

Keywords: Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Data Mining, Clustering Analysis, Ontology of Language.

Abstract. The clusters’ analysis process comprises two broad activities: generation of a clusters set and extracting

meaning from these clusters. The first one refers to the application of algorithms to estimate high density ar-

eas separated by lower density areas from the observed space. In the second one the analyst goes inside the

clusters trying to figure out some sense from them. The whole activity requires previous knowledge and a

considerable burden of subjectivity. In previous works, some alternatives were proposed to take into ac-

count the background knowledge when creating the clusters. However, the subjectivity of the interpretation

activity continues to be a challenge. Beyond soundness domain knowledge from specialists, a consensual in-

terpretation depends on conversational competences for which no support has been provided. We propose a

method for cluster interpretation based on the categories existing in the Ontology of Language, aiming to

reduce the gap between a cluster configuration and the effective extraction of meaning from them.

1 INTRODUCTION

The clusters' analysis process can be seen as the

search for a model on unlabeled data for which no

class structure is known. To accomplish it, first it is

generated a configuration of clusters on the basis of

the object dimensions, in which high density groups

of objects are separated from other by low density

areas. So, the clusters’ interpretation (CI), a typical

human activity, takes place. Such a subjective activ-

ity is, usually, carried out with no reasoning order to

guide the use of the ontological categories that could

express this subjectivity. Such a mental ordering

could be helpful as a way to make explicit (yet sub-

jective) the rationale that justify the conclusions.

The start point for this work is the acknowledgment

that CI, as any human phenomena, occurs in the

Language domain. Under such a premise, it is

worthwhile the aphorism “Everything said is said by

someone”, by Maturana (1988). In other terms,

“Everything said is said by an observer”. In CI, it

means that it is not possible to talk about interpreta-

tion, nor even about the object of this interpretation

(the clusters), without considering the analyst, or the

subject who performs the analysis (the observer).

This fact has, at least, two immediate consequences.

The first is that, by bringing to the scene the ob-

server as a fundamental player to CI, his/her mental

models are also brought (Senge, 1994; Kofman,

2002). These models represent the way s/he ob-

serves and analyses the world, his/her distinctions,

365

Francisco Castilho W., José de Lucena Filho G., Antonio do Prado H. and Ferneda E. (2006).

A METHOD BASED ON THE ONTOLOGY OF LANGUAGE TO SUPPORT CLUSTERS’ INTERPRETATION.

In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - AIDSS, pages 365-368

DOI: 10.5220/0002470003650368

Copyright

c

SciTePress

positions, narratives, concerns, life experiences, or,

for short, his/her complete self. While sharing a way

of (a human) being with others, s/he is distinguished

from them by the set of characteristics that makes

him/her the particular being that s/he is (Echeverria,

1997, 1999). And this defines how s/he aggregates

semantic value during CI.

The other consequence refers to the necessity to

consider the linguistic dimension, as proposed by the

Ontology of Language (OL). OL considers that

language permeates the whole process, including the

interaction between the analyst and the domain ex-

pert when searching for new knowledge, the data

structure, and the previous domain knowledge. In

this dimension, it can be considered the fundamental

linguistic acts, presented by Echeverria (1997), em-

phasizing the importance of judgments.

To this ontological perspective, it can be added

the epistemological one, also fundamental to aggre-

gate semantic value to CI. In the epistemological

perspective, the focus is shifted not only from the

analysis object (the clusters) and the analysis itself,

but also from the analyst (the observer), coming up

with the domain meta-knowledge.

In this paper, we present briefly a proposal to ap-

ply OL on CI activity, describe a case study, report

some results, and point out some future works.

2 THE METHODOLOGY

For Echeverria (1997), the central assumptions of

the OL may be summarized as follows: (a) Human

beings are linguistics beings. As an assumption, it is

important to understand that this is also an interpre-

tation. According to the main thesis of the OL, [we

don’t know how things are. We only know how we

observe them or how we interpret them to be.] we

live in a world of interpretations (Echeverria,

1997b). So, we can never say how things really are;

we just can say how we assume, interpret or take

them to be; when we say that human beings are

linguistic beings, what we are really saying is that

we interpret human beings to be linguistic beings.

Then, it is the language that makes human beings the

particular kind of beings we are. (b) Language has a

generative nature. Again, what is meant here is that

“we interpret language to be generative”. As such,

language not only describes reality – the way we, in

our community, observe ourselves and the world

around us – but also creates such realities. Language

is action, what makes it able to build future, to gen-

erate identities and the world in which one lives.

Language generates being. (c) Human beings build

themselves in the dynamics of language. To be hu-

man is not, then, to have pre-determined nor perma-

nent ways of being; to be human is, above all, to

create and recreate spaces of possibilities, through

language.

But what are the implications of these assump-

tions on the CI process? The answer has to do with

the way of implementing the space of possibilities.

Obviously, it happens by means of Language and, in

particular, of conversations!

In the conversations there are two classes of ba-

sic linguistic acts (Echeverria, 1997): the assertions

and the declarations. In the class of declarations

there are the assessments, which are central for the

sake of the interpretation method we are introducing

in this work, and the promises (the commitments),

that initiate or derive from petitions or offers (both,

types of declaration) followed by a typical accept

declaration, such as a “yes”, for example.

Assertions are descriptions of the state of the

world through which one describes what observes

according to the distinction that s/he possesses. In

other terms, we say that assertions are statements

intended to be facts. We use to say that the word

follows the world, as if this world already existed.

Declarations change the state of the world. To

declare something is to establish as the world may

become, adjusting itself to what has been said and,

thus, creating new contexts, new spaces of possibili-

ties. In this case, we say, the world follows the word;

after a declaration new choices become possible.

Assessments, like verdicts, are judgments and

inherit from declarations the power to establish

changes in the world, in particular, for all those

actors involved in the assessment: the one who

makes the assessment, the one who/which is as-

sessed and all those who assigns or recognizes au-

thority and acceptance to the assessment. Assess-

ments constitute a new reality, a reality that inhabits

in the intrinsic interpretations which support them.

Besides, assessments live in the person who makes

it, not on the “object” which is being assessed. As-

sessments are formulated almost every moment and

each time we face something new; in these occa-

sions they are formulated almost automatically.

As with all declarations, assessments can be

valid or invalid, depending on the authority of whom

that has formulated them. Moreover, they can be

founded (or not) according to their adherence to a set

of related aspects.

In general, the process of founding assessments

is crucial for people coordination of actions in living

together. This is also true when the living process

has to do with people interactions within the CI

ICEIS 2006 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

366

context as it happens, for example, in the conversa-

tions between the analyst and the domain specialist.

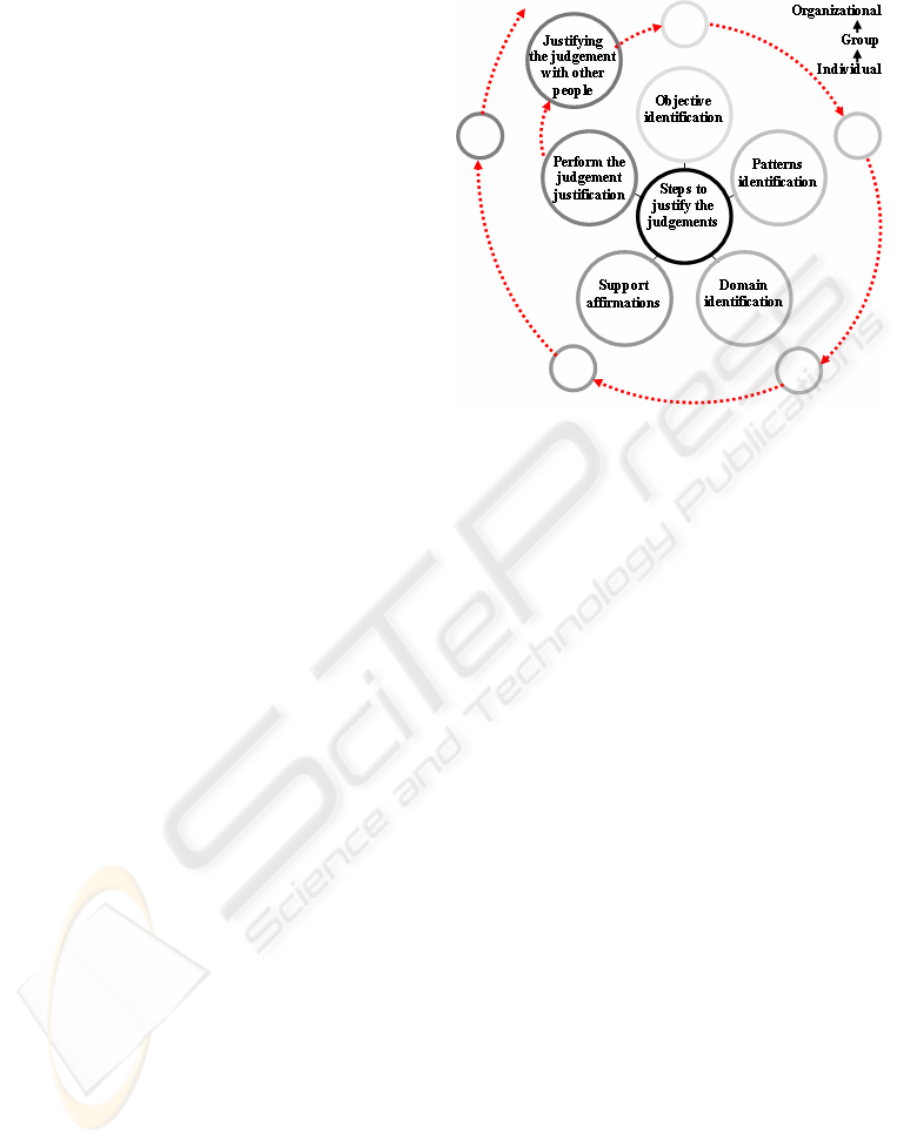

The steps for founding assessments are (Echever-

ria, 1997): (1) Identify the future projected action

(i.e. the purpose) that you have in mind when issu-

ing the assessment. There is always a purpose when

one issues a judgment. (2) Identify the standards

under which the assessment is being made, with

relation to the future projected action. (3) Identify

the particular domain of observation under which the

assessment is being made. (4) Identify the assertions

(facts and events) related to the chosen standards,

that you can offer to support the assessment. (5) As a

counterpoint (refutation), verify that the opposite

assessment cannot be founded.

Actually, there are at least two other good rea-

sons for inclusion of a sixth step in the previous

process for founding assessments. First reason is

derived from the central thesis of the OL stated be-

fore, when we say that “we don’t know how things

are; we only know how we observe them or how we

interpret them to be” (Echeverria, 1997b). So, it

becomes very natural a compelling need for us for

willing to share the founding process with other

people. The other reason has to do with an epistemo-

logical dimension (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995) of

knowledge creation, through which the additional

step contributes to establish an spiral expansion,

from individual to groups and organizational levels,

and thus contributing to expanding the CI process

from mere individual views to a more collective

fashioned way (Castilho et al, 2004). The sixth step

is: (6) To share the founding process with other

people, by opening the previous cycle in an enlarged

spiral whose specific effect (as a byproduct) is an

expanding consensual space of knowledge construc-

tion. Figure 1 presents the founding assessments

procedure, encompassing activities from the indi-

vidual to the group and organizational level.

For Echeverria (1997), assessments that do not

resist to the first five steps can be considered not

founded. To share the founding process with other

people (the step 6), besides contributing to reveal

one’s possible cognitive blindness, serves also to

reinforce the outcome of the founding procedure. It

is interesting to notice that the more collective,

grounded, and sound are the processes of decision

making embedded in it, the more trustful the result

of CI. From the founding procedure, its collective,

ground and sound aspects depend on a disciplined

way of giving and receiving (well founded) assess-

ments and on the schema or protocols for coordinat-

ing actions.

Figure 1: Procedure for justifying judgements: from indi-

vidual to organizational level

.

3 CASE STUDY

The AA process was feed by data extracted from the

Brazilian National System of Sanitation Information

(SNIS). Complementary data regarding to the Eco-

nomic Value Added (EVA) were extracted from the

financial reports issued by each State Company of

Basic Sanitation (CESB). This data set refers to the

CESB performance w.r.t. economic, financial, and

operational results.

The phase of objectives definition was carried

out during the interaction between the expert and the

analyst. The objectives, defined by agreement, are:

(1) create three clusters of CESB using data related

to their economic, financial, and operational per-

formance; (2) verify the effects of different level of

variables weighting on the clusters configuration;

(3) aggregate domain and data structure knowledge.

Three experiments were performed in two stages,

two in the first stage and one in the second. Experi-

ment E

XP

1

took nine performance indexes with no

weighting, while EXP

2

used the same indexes with a

weighting factor. Three clusters were created and the

results compared. In the second stage, E

XP

3

used an

aggregation of performance indexes, including six

economic, financial, and operational performance

and three indexes that compound the EVA. The

results in the third experiment were compared

against the two previous ones. The purpose of E

XP

3

was to serve as a reference to issue a judgment re-

garding to the best cluster configuration. Since the

indexes used in E

XP

3

reflect mathematically the

A METHOD BASED ON THE ONTOLOGY OF LANGUAGE TO SUPPORT CLUSTERS’ INTERPRETATION

367

performance indexes, we consider this result as the

reference for the better configuration.

To generate the clusters it was used the informed

version of K-means that considers an information

matrix. This matrix takes into account the correla-

tion metrics and the graduation of interest and rele-

vance among the attributes. The interest and rele-

vance information was provided by the expert, ac-

cording to the weighting model proposed by Cas-

tilho et al (2003, 2004, 2005). To assure the sensibil-

ity control of the algorithm w.r.t. the initial condi-

tions, the same seeds were used for all experiments.

These seeds were previously defined at random. We

let no limit for data items allocation, allowing the

algorithm to converge to the maximum performance

criterion. To facilitate the results evaluation, a set of

graphical views were provided to the expert.

As in almost all human activity, the knowledge

discovering process is a social construction that

emerges from the interaction among people (Berger

& Luckmann, 2001). By this way, conversation

inside the conceptual frame of OL is vital to carrying

out the CI activity. So, it is important to consider

that the linguistic dimension is where the conversa-

tions take place and the overall knowledge discover-

ing process occurs. The results evaluation is perme-

ated by conversations between the expert and the

analyst and consists of building shared judgements

on the basis of the clustering configuration pre-

sented. In this sense, the expert and the analyst con-

cluded that E

XP

2

were more coherent with the objec-

tives. After some conversations, the judgement justi-

fication process was carried out adopting as refer-

ence the results of Exp

3

. Some support statements

were proposed by the expert and the justification of

the contrary judgments were presented by the ana-

lyst. At first, the best clusters configuration, were

achieved by E

XP

1

. However, after performing a

conversation cycle including a second expert, the

clusters configuration in Exp

2

were taken as the

more adequate for the application objectives.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The main advantage of our methodology is the mod-

elling of the subjective problem of CI, with the con-

scious handling of the ontological categories in-

volved. The domain experts declared satisfied with

the accomplished results and the quality and effec-

tiveness of the conversations and relationships de-

veloped during the CI activity. It is not usual in the

KDD realm to consider explicitly the mental proc-

esses involved when performing cluster analysis.

Rather, some data miners emphasize the importance

of the algorithms to generate the clustering model. It

seems that, once the clustering model is delivered,

their work is finished. They do not devote the neces-

sary importance to CI activity as a social knowledge

creation process. We suggest a coordination of ac-

tion cycle in clusters’ analysis that involves the

analyst and the expert in a creation process, based in

the distinctions of the linguistic acts and the con-

scious handling of the conversation dynamics.

On the application side, our experiments suggest

that management performance keeps in pace with

economic performance, i.e., a good management

aggregates wealth, while a bad one destroy it.

Our next targets are (1) deepen the studies in OL

aiming to improve the evaluation results and

(2) propose alternatives to represent and process

previous knowledge to have more semantic clusters.

REFERENCES

Berger, P.L., Luckmann, T., 1967. The Social Construc-

tion of Reality, Anchor.

Castilho, W.F., Prado, H.A., Ladeira, M., 2003. Introduc-

ing prior knowledge into the clustering process. In 4

th

Int. Conf. on Data Mining. pp. 171-181.

Castilho, W.F., Prado, H.A., Ladeira, M., 2004. Informed

k-means: a clustering process biased by prior knowl-

edge. In ICEIS’04, pp. 469-475.

Castilho, W.F., Prado, H.A., Lucena Filho, G.J., Ferneda,

E., 2005. Informed Clustering: aggregation of seman-

tics to the clustering process. In 2

nd

International Con-

ference on Information Systems and Technology Man-

agement. São Paulo, Brazil. (In Portuguese)

Echeverria, R., 1997. Ontology of Language. Dolmen

Ediciones. Santiago, Chile, 4ª edition. (In Spanish)

Echeverria, R., 1997b. What Is The Ontology Of Lan-

guage? In http://www.newfieldconsulting.com/

publicaciones/the_ontology_of_language.pdf.

Echeverria, R., 1999. The observer and the changing self.

Futures 31, pp. 818-821.

Kofman, F., 2002. Metamanagement –

the new business

awareness. Antakarana Cultura Arte Ciência. São Pau-

lo, Brazil. (In Portuguese)

Maturana, H., 1988. Reality: the search for objectivity or

the quest for a compelling argument. The Irish Journal

of Psychology, vol. 9 (1), pp. 25-82.

Maturana, H., 1992. The Sense of Human. Hachette. Santi-

ago, Chile. (In Spanish)

Nonaka, I, Takeuchi, H., 1995. The Knowledge-Creating

Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dy-

namics of Innovation, Oxford University Press.

Senge, P.M., 1994. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and

Practice of the Learning Organization. Currency.

ICEIS 2006 - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS

368