AN ONTOLOGY FOR A WEB DICTIONARY

OF ITALIAN SIGN LANGUAGE

Rosella Gennari

KRDB, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Piazza Domenicani 3, 39100 Bolzano, Italy

Tania di Mascio

University of L’Aquila, I-67040 Monteluco di Roio, L’Aquila, Italy

Keywords:

Ontology and the semantic web, knowledge management, web-based education.

Abstract:

Sign languages are visual languages used in deaf communities. They are essentially tempo-spatial languages:

signs are made of manual components, e.g., the hand movements, and non-manual components, e.g., facial

expressions. The e-LIS project aims at the creation of the first web bidirectional dictionary for Italian sign

language–verbal Italian. Whereas the lexicographic order is a standard and ‘natural’ way of ordering hence

retrieving words in Italian dictionaries, there is nothing similar for Italian sign language dictionaries. Stokoe-

based notations have been successfully employed for decomposing and ordering signs in paper dictionaries

for Italian sign language; but consulting the dictionaries requires knowing the adopted Stokoe-based notation,

which is not as easy-to-remember and well-known as Italian alphabet is. Users of a web dictionary cannot be

expected to be expert of this. There the role of ontologies comes into play. The ontology presented in this

paper analyses and relates the formational components of a sign; in some sense, the ontology allows us to

‘enrich’ the e-LIS dictionary with expert information concerning classes of sign components and, above all,

their mutual relations. We conclude this paper with several open questions at the intersection of knowledge

representation and reasoning, semantic web, sign and computational linguistics.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sign languages are visual languages used in deaf

communities, mainly. They are essentially tempo-

spatial languages, simultaneously combining shapes,

orientations and movements of the hands, as well as

non-manual components, e.g., facial expressions. A

sign language and the verbal language of the coun-

try of origin are generally different languages. The

creation of an electronic dictionary for Italian sign

language is part of the e-LIS project (E-LIS project,

2004), which is lead by the European Academy of

Bozen-Bolzano. The project commenced at the end of

2004 with the involvement of the ALBA cooperative

from Turin, active in deaf studies. Section 2 outlines

the essential background on Italian sign language and

the e-LIS project’s history.

Initially, the e-LIS dictionary from Italian sign

language to verbal Italian was intended for expert

signers searching for the translation of an Italian sign.

At the start of 2006, when the development of e-LIS

was already in progress, it was realised that potential

users of a web dictionary would also be non-experts

of Italian sign language. Then the idea of an ontol-

ogy and the associated technology for the dictionary

took shape. We explain our ontology in Section 3, and

comment on it in Section 4. Section 5 outlines the ar-

chitecture of the ontology-driven dictionary, and the

role that our ontology plays in it. In Section 6, we

compare our ontology-driven dictionary to other elec-

tronic dictionaries for sign languages. Section 7 con-

cludes this paper with an assessment of our work and

several open questions.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Sign Language and Dictionaries

A sign language (SL) is a visual language based on

body gestures instead of sound to convey meaning.

SLs are commonly developed in deaf communities.

206

Gennari R. and di Mascio T. (2007).

AN ONTOLOGY FOR A WEB DICTIONARY OF ITALIAN SIGN LANGUAGE.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Web Interfaces and Applications, pages 206-213

DOI: 10.5220/0001276302060213

Copyright

c

SciTePress

They can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple

and concrete to the lofty and abstract.

Contrary to popular belief, SL is not universal;

SLs vary from nation to nation; even more, SLs such

as Italian sign language (LIS) have dialects of their

own. LIS is not a visual rendition of Italian verbal

language; LIS has a grammar, syntax and lexicon of

its own, e.g., a word can be translated into more than

one sign and vice versa (see Figure 1).

As highlighted in (Pizzuto et al., 2006), SLs can

be assimilated to verbal languages “with an oral-only

tradition”; their tempo-spatial nature, essentially 4-

dimensional, have made it difficult to develop a writ-

ten form for them. “However” — as stated in (Piz-

zuto et al., 2006) — “Stokoe-based notations can be

successfully employed primarily for notating single,

decontextualized signs”

1

. As such, they are used to

transcribe signs and order them in (Radutzky, 2001),

a paper dictionary of LIS to Italian.

The transcription is based on a decomposition of

signs into so-called ‘formational units’. The fol-

lowing classes correspond to the formational units

adopted in (Radutzky, 2001):

• the handshape class collects the shapes the

hand/hands takes/take while signing; this class

alone counts more than 50 terms in LIS;

• the orientation class gives the the palm orienta-

tions, e.g., palm up;

• the movement of the hand/hands class lists the

movements of the hands in LIS;

• the location of the hand/hands class provides the

articulation places, i.e., the positions of the hands

(e.g., on your forehead, in the air).

Let us see an example entry of (Radutzky, 2001): the

sign for “parlare dietro le spalle” (to gossip behind

one’s back) in Figure 1 is a one-hand sign; the hand-

shape is flat with five stretched fingers; as for the ori-

entation, the palm orientation is forward and towards

the left so that the hand fingers get in touch once with

the location which is the neck; as for the movement of

the hand, this moves to the left only once.

This information is readable in the transcription

in the upper-left corner of Figure 1 (namely, B

⊥<

Π

∗•

). However, figuring out this information from the

transcription requires some expert knowledge of the

adopted transcription system and, above all, of the un-

derlying formational rules of signs.

Before proceeding further, a word on the written

representation of SLs is in order. The representation

of SLs in written form is a difficult issue and a topic

1

They were adopted for transcribing and ordering Amer-

ican signs in (Stoke et al., 1965).

Figure 1: Sign for Italian expression Parlare dietro le spalle,

as in (Radutzky, 2001).

of current research, e.g., see (Garcia, 2006; Pizzuto

et al., 2006). We do not discuss this here for it goes

beyond the scopes of our work which, at present, is of

experimental nature mainly.

2.2 The E-lis Project

The e-LIS dictionary is part of a research project lead

by the European Academy of Bozen-Bolzano (EU-

RAC); e-LIS stands for dizionario Elettronico per la

Lingua Italiana dei Segni (Electronic dictionary for

LIS).

The project was conceived at the end of 2004 at

EURAC (E-LIS project, 2004). The ALBA coopera-

tive from Turin, active in deaf studies, was involved in

the project for the necessary support and feedback on

LIS. As clearly stated in (Vettori et al., 2004), most

sign language dictionaries form a hybrid between a

reference dictionary and a learner’s dictionary. On the

contrary, the e-LIS dictionary is conceived a ‘semi-

bidirectional dictionary’, explaining LIS signs using

LIS as meta-language and vice-versa.

The electronic format is particularly suited to an

SL; for instance, it allows for videos and animations

to be integrated in the dictionary and used to render

the movement of signs in space. Since the dictionary

aims at reaching as many users as possible, it was con-

ceived as a web application.

However the dictionary from LIS to verbal Italian

was initially intended only for expert signers search-

ing for the translation of a sign into verbal Italian.

Only subsequently it was realised that the potential

users of a web dictionary could also be non-experts

of LIS, willing to learn it; we cannot expect that they

become expert of the transcription system outlined in

Subsection 2.1 and, in particular, that they know how

to compose the formational units of signs of that sys-

tem. Then, at the start of 2006, we commenced to

AN ONTOLOGY FOR A WEB DICTIONARY OF ITALIAN SIGN LANGUAGE

207

work on a domain ontology (Guarino, 1998) for the

LIS-to-Italian dictionary of e-LIS in order to repre-

sent and make available to all such a knowledge.

In the following Sections 3 and 4, we focus on the

domain ontology at the core of our ontology-driven

dictionary, whose architecture is outlined in Section 5.

3 THE DOMAIN ONTOLOGY

The domain of our e-LIS ontology is the Stokoe-based

classification outlined in Subsection 2.1 above. The

ontology was constructed in a top-down manner start-

ing from (Radutzky, 2001) with the expert assistance

of linguists and deaf users of the e-LIS project (see

Subsection 2.2). It was designed using the ICOM on-

tology editor (Fillottrani et al., 2006).

Note that our ontology is ‘richer’ than that clas-

sification: the ontology introduces novel classes and

relations among classes, thereby making explicit rel-

evant pieces of information which were implicit and

somehow hidden in that classification and in the ref-

erence paper dictionary. For instance: it makes ex-

plicit that each one hand sign is composed of at least

one handshape by introducing an appropriate relation

among the corresponding classes, One-hand sign and

Handhsape; it groups together all the twelve different

types of cyclic movements of hands in the Movement

in circle class, not present in the paper dictionary.

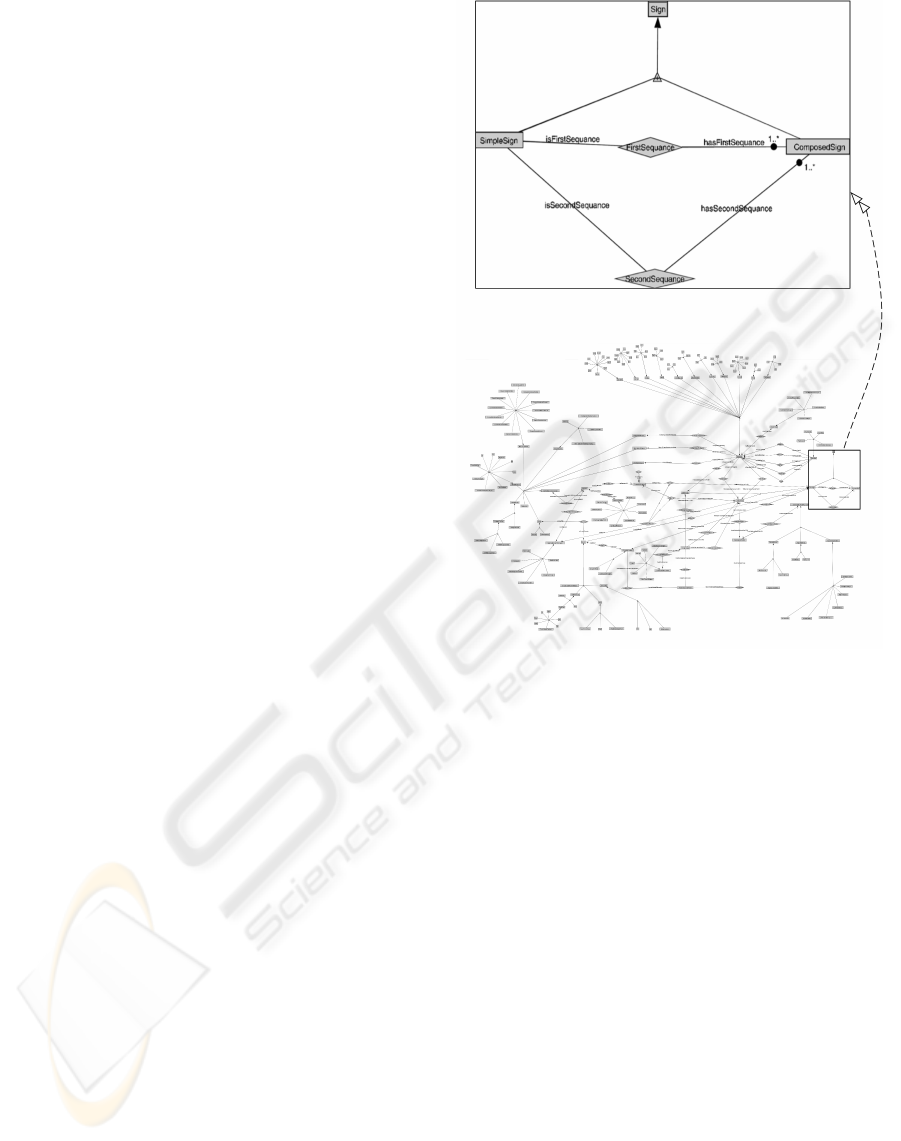

The current domain ontology in diagrammatic for-

mat and a snippet of it are shown in Figure 2 (see also

the high-resolution version (E-LIS ontology, 2006)).

In the remainder, we focus on the main classes and re-

lations of the ontology, explaining their role and our

motivations for their creation. We restrict our expo-

sition to the essential features of the ontology. For

instance, cardinality constraints are missing in our be-

low exposition, because they can be easily understood

from our ontology available online at (E-LIS ontol-

ogy, 2006). However, note that they are integral part

of our domain ontology.

3.1 Composed and Simple Signs

Some LIS signs are ‘composed’ of ‘simpler’ signs; for

instance, a composed sign may specify two locations

for the dominant hand location, that is, the initial lo-

cation and the final location the hand assumes due to

a certain movement. To account for this distinction in

our ontology,

• the Sign class is partitioned into the Composed

sign and Simple sign subclasses (see the top of the

ontology snippet in Figure 2),

Figure 2: At the bottom: the ontology diagram. At the

top: a snippet of the ontology diagram. See also the high-

resolution version (E-LIS ontology, 2006).

• two relations are introduced between the Simple

sign and Composed sign classes, stating that each

composed sign is made precisely of two simple

signs (see First sequence and Second sequence in

the ontology snippet in Figure 2).

The One-hand sign and Two-hand sign classes form

a partition of Simple sign, meaning that each sim-

ple sign is either a one-hand sign or a two-hand sign.

By inspection of (Radutzky, 2001), we abstracted the

rule-based definitions of one-hand sign and two-hand

sign provided in Table 1 in BNF-notation, where: H

stands for handshape; Loc gives the hand location; O

specifies the palm orientation; C stands for the con-

tact location of the hand; R gives the hand relational

position and occurs in two-hand signs only; MovSeq

is a sequence of at most three movements (M). All

can be referred to the dominant hand (DH) or the

non-dominant hand (NDH), except R that can only be

referred to the non-dominant hand — the dominant

hand is the right hand and the non-dominant hand is

the left hand for a right-handed person.

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

208

Table 1: Definitions of One-hand sign and Two-hand sign

as in the e-LIS domain ontology.

MovSeq:

M | M M | M M M

One-hand sign:

H

DH

Loc

DH

MovSeq |

H

DH

O

DH

Loc

DH

MovSeq |

H

DH

C

DH

Loc

DH

MovSeq |

H

DH

O

DH

C

DH

Loc

DH

MovSeq

Two-hand sign:

H

NDH

One-hand sign |

H

NDH

O

NDH

One-hand sign |

H

NDH

R

NDH

One-hand sign |

H

NDH

O

NDH

R

NDH

One-hand sign

For instance, according to this definition, both

one-hand signs and two-hand signs specify the hand-

shape (H) and location (Loc) of the dominant hand

(DH); moreover the two-hand sign also specifies the

handshape of the non-dominant hand (NDH).

Our e-LIS ontology makes explicit these rules for

the One-hand sign and Two-hand sign classes and the

related subclasses; we explain how in the remainder

of this section. In particular, whenever the domi-

nant or the non-dominant hand relate two of these

classes, we have a corresponding relation in the on-

tology. For instance, the ontology has two relations

between Handhsape and Two-hand sign, one concern-

ing the handshape of the dominant hand, and the other

concerning the handshape of the non-dominant hand;

instead, the ontology sets only one relation for the

handshape of one hand (the dominant hand) between

Handhsape and One-hand sign. In this manner, the

implicit semantics of one-hand signs and two-hand

signs is correctly represented.

3.2 Location and Contact with Location

As specified in Table 1, contact with location and lo-

cation are properties of both one-hand signs and two-

hand signs, but they pertain to the dominant hand only

(

∗

). In our ontology, One-hand sign and Two-hand

sign partition Simple sign. Then, to account for (

∗

),

the ontology has a relation named DHContactWith-

Location between the Simple sign and Contact with

location classes, and a relation named DHLocation

between the Simple sign and Location classes.

Location. The Location class is subdivided into

four main subclasses:

• Neutral space in front of the body;

• Arm or its part (divided in Wrist, Arm, Non dom-

inant hand);

• Trunk (divided in Lower trunk and hip, Chest,

Shoulders and upper trunk);

• Neck and above (divided in Neck, Whole face,

Part of face).

In turn, the Part of face subclass of Neck and above is

divided into:

• Cheek;

• Chin;

• Eye;

• Top and sides of the head;

• Mouth;

• Nose;

• Ear.

All the above classes, with the exception of the fol-

lowing abstract concepts

• Arm or its part,

• Trunk,

• Neck and above,

• Part of face,

are also listed as locations in the paper dictionary.

Contact with location. By inspection of (Radutzky,

2001), we can see that there are two possible kinds of

location contacts: the first one is the hand contact and

the other one is the finger contact. Thus in our ontol-

ogy we have the Contact with location class divided

into two subclasses, namely,

• Contact with hand,

• Contact only with fingers.

We have then a relation between the Contact with lo-

cation class and the related Location class to express

the contact of either the hands or the fingers with a

body location. The ontology has also a relation be-

tween the Contact with location class and the Hand

or hands initial position class to express that the con-

tact with location has to be specified for the initial

position of the dominant hand, in two hand signs or

one hand signs.

3.3 Movement

The movement category is the most complex one. The

whole movement is made of one or more sequences,

which are built out of one single movement of the

hand/hands (see Table 1). To account for this be-

haviour, the ontology has the Movement in sequence

class and the Movement class, as well as a relation

between them to express that the Movement in se-

quence class is responsible for building sequences of

movements. Some components of the movement con-

cern the dominant hand while others concern the non-

dominant hand (see 184.2 in (Radutzky, 2001)), but

AN ONTOLOGY FOR A WEB DICTIONARY OF ITALIAN SIGN LANGUAGE

209

‘which is which’ is not made explicit by the classifica-

tion adopted in the paper dictionary (see Table 1); thus

the ontology has two types of relations, one for the

dominant and the other for the non-dominant hand,

and involving the Movement in sequence class.

Furthermore, the movement in sequence property

is common to the One-hand sign and Two-hand sign

classes; the ontology expresses this via a relation be-

tween the Simple sign class and the Movement in se-

quence class.

The Movement attribute class provides attributes

of the Movement class, and is subdivided in:

• Elbow stretch-

ing;

• Slow movement;

• Held movement;

• Stretched move-

ment;

• Continuous movement;

• Finger sequential move-

ment;

• One time repeated;

• Alternating movement.

A movement is built out of two kinds of components:

• one-hand movement component;

• relational movement component.

The ontology expresses this via the related subclasses

of the Movement class, explained below.

One-hand movement. The One-hand movement

class is itself divided into:

• Movement in circle, e.g., convex clockwise

frontal;

• Directed movement, e.g., up and down;

• Finger movement, e.g., crumbling;

• No movement;

• Touch, e.g., with hand;

• Wrist movement, e.g., twisting at the wrist.

The above classes are further partitioned as in the pa-

per dictionary. In the ontology (and not in the paper

dictionary), the Touch subclass has a relation with the

Location class; this relation makes it explicit that the

movement of type “touch” is related to the signer’s

body or the neutral space in front of the body. In

the latter case the sign is a two-hand sign (see 700.1

in (Radutzky, 2001)).

Relational movement. The Relational movement

class characterizes all the movements of a hand with

respect to the other. It is thus divided into:

• Hand insertion;

• Crossing hands;

• Hands away

from each other;

• Hands towards each other;

• Change place of hands;

• Hands interlinking.

The Relational movement class has a relation with

the Two-hand sign class to express that the relational

movement applies to two-hand signs only. To make it

clear that this relation concerns both hands, we made

the relation inherit from

• the relation between the Simple sign and the

Movement in sequence classes, and concerning

the dominant hand,

• the relation between the Two-hand sign and the

Movement in sequence classes, and concerning

the non-dominant hand.

3.4 Handshape

Now we focus on the handshape category, which is

specified for the dominant hand only in one-hand

signs, and for both hands in two-hand signs (see Ta-

ble 1). Therefore our ontology explicitly introduces

a relation between One-hand sign and Handshape,

and two relations between Two-Hand sign and Hand-

shape.

The Handshape class is divided in the eleven sub-

classes of handshapes listed in (Radutzky, 2001):

• Extensions;

• Opening

• Closing;

• Closed;

• Crumblinglike;

• Round shaped;

• Closed fists;

• Rectangular;

• Curved;

• Flat shaped;

• Others.

Each of the above subclasses is further subdivided as

in the paper dictionary, and there is nothing new in

our ontology with respected to this.

Let us turn to something new. By careful in-

spection of the paper dictionary, one sees that the

handshape changes due to the following movements

(a critical feature for the interface design of the e-

LIS dictionary driven by the ontology): closing hand

or fingers; opening hand or fingers; configuration

change. To express this information in the ontology

we have three relations between the Handshape and

the Closing hand or fingers, Opening hand or fingers,

Configuration change classes. Moreover we have five

relations for all the fingers of the hand between the

Handshape and Finger state classes.

Note that the Finger state class is not present

in (Radutzky, 2001). We have it explicitly in our on-

tology to show that the configuration depends on a

given state of the fingers. It is divided into:

• Finger closed;

• Finger

straight;

• Finger bent;

• Finger bent at palm knuckles.

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

210

The Handshape change class is not present in the

paper dictionary, however it is used in it (e.g., see

361.3). Another new class is the Finger contact class.

It is divided into:

• Thumb with middle fin-

ger;

• Thumb with little finger;

• Thumb with index fin-

ger;

• Thumb with ring fin-

ger;

• Index finger with

middle finger.

3.5 Palm Orientation

As in the case of the handshape, the palm orientation

is specified for the dominant hand in the one-hand

sign, for both hands in the two-hand signs. Then the

ontology has a relation between One-hand sign and

Palm orientation for the dominant hand, and two re-

lations between Two-hand sign and Palm orientation,

one for the dominant hand and the other for the non-

dominant hand.

According to the paper dictionary, the palm orien-

tation has to be specified for the initial position of the

hand/hands. To express this, the ontology has a rela-

tion between the Palm orientation class and the Hand

or hands initial position class.

Then the Palm orientation class is subdivided into:

• Palm towards the

signer;

• Palm down;

• Palm up;

• Palm away from the

signer;

• Palm left;

• Palm right.

3.6 Hands Relational Position

The relational position of the hands pertains to two-

hand signs (see Table 1); thus the ontology has a

relation between the Hands relational position and

Two-hand sign classes. The Hands relational posi-

tion class is subdivided into into three main classes:

Right-left contact, e.g., contact with elbow; Right-left

distance, e.g., hands interlinked; Right-left spatial po-

sition, e.g., one hand inside the other. These are fur-

ther partitioned and related as specified in (E-LIS on-

tology, 2006).

4 CONCLUDING REMARKS

Regarding the handshape, location and movement for-

mational components of signs, some observations are

in order. They are not part of the ontology in its cur-

rent form. In the future, after collecting more de-

tailed information of the LIS domain, the observa-

tions could be turned into axioms of the ontology —

e.g., in the form of description logic formulae; they

could be used to improve and shorten up the sign com-

position process. We discuss some of them as follows.

4.1 Handshape and Location

A relevant observation (Volterra, 2004) is that, in

the asymmetric signs, the open-hand and closed-fist

handshapes are very frequent for the non-dominant

hand. Alas, as such this piece of information is still

too vague for us; first, the exceptions to the rule need

to be pin down; then the rule, modulo the exceptions,

can be added to the ontology as an axiom. In this

manner the user who is looking up for an asymmet-

ric sign can only select those handshapes for the non-

dominant hand, modulo the exceptions.

The dominant hand and the non-dominant hand

may have the same location. This is generally true

for the simple two-hand signs. However, an excep-

tion to the above rule is given by signs with non-

dominant hand, arm or wrist as locations — see 108.1

in (Radutzky, 2001). As for the composed signs, we

found some counter-examples where the locations for

the dominant hand and non-dominant hand are differ-

ent (see 197.3 and 184.2 in (Radutzky, 2001)).

4.2 Movement

As stated in Table 1, some components of the

movement can concern the dominant hand while

others concern the non-dominant hand (see 184.2

in (Radutzky, 2001)), but ‘which is which’ is unclear.

However, if the movement is composed of relational

movement components (e.g., hands away from each

other), the movements of the hands are clearly speci-

fied and this information can be turned into axioms.

By careful inspection of (Radutzky, 2001), one

can see that most of the two-hand signs with iden-

tical handshape and palm orientation have symmet-

ric or alternating movements (e.g., see 741.1 or 140.3

in (Radutzky, 2001)). Currently, this cannot be spec-

ified as a general rule; by way of contrast, see 630.2

in (Radutzky, 2001).

5 THE ONTOLOGY-DRIVEN

DICTIONARY

As claimed above, an ontology-driven dictionary al-

low us to develop a intensional navigation of the LIS-

to-Italian dictionary, so that also non-experts can use

the dictionary. But how?

AN ONTOLOGY FOR A WEB DICTIONARY OF ITALIAN SIGN LANGUAGE

211

The first step of the development consisted in the

creation of the domain ontology explained above; this

analyses, makes explicit to all and represents how

signs are decomposed in an unambiguous way. By

revealing implicit information or wrong assumptions,

the domain ontology helped improve the flow of in-

formation within the e-LIS team. As such, it played

an important role in the requirement analysis and

conceptual modelling phase of the e-LIS database

schema. The ontology was developed in ICOM hence

we could use a DIG-enabled DL reasoner to check

that the decomposition rules of the ontology are con-

sistent (Fillottrani et al., 2006).

Moreover, the domain ontology serves as the basis

for the definition of the application ontology which

is tuned to the data present in the e-LIS database.

The application ontology then becomes the input of a

DIG-enabled query tool like (Catarci, T. et al., 2004);

the two main modules of this tool are the Compose

module for assisting the user in effectively compos-

ing a query, and the Query module for directly spec-

ifying the data which should be retrieved from the

data sources. In particular, with input the LIS on-

tology, Compose will propose sign components (on-

tology classes) which are related to the user’s cur-

rent selection, as specified in the ontology; e.g., if the

user selects “one-hand sign” then the query tool will

not show “hands relational position” as next possible

choice to the user, because the ontology does not re-

late these concepts. We refer the reader to (Catarci, T.

et al., 2004) for more on the query tool and its inter-

gration with a database.

The visualisation tool is the other main compo-

nent of the ontology-driven dictionary. The visuali-

sation of the composition, query process and results

should meet the needs of the different users of the

dictionary; for instance, deaf users are ‘visual reason-

ers’ (Sacks, 1989) hence their visual reasoning strate-

gies must be considered as well.

6 RELATED WORK

Electronic dictionaries for SLs offer numerous advan-

tages over conventional paper dictionaries; they can

make use of the multimedia technology, e.g., video

can be employed for rendering the hand movements.

In the remainder, we review available electronic dic-

tionaries from an SL to the verbal language of the

country of origin, which are of interest to our work.

The bilingual Multi-Media Dictionary for Amer-

ican SL (MM-DASL) (Wilcox, 2003) developed a

special user interface, with film-strips or pull-down

menus. This allows users to look up for a sign only

reasoning in terms of its visual formational com-

ponents, that is, the Stokoe ones (handshape, loca-

tion and movement); search for signs is constrained

via linguistic information on the formational compo-

nents. Users are not required to specify all the sign’s

formational components, nevertheless there is a spe-

cific order in which they should construct the query.

Since the domain ontology embodies semantic infor-

mation on the classes and relations of sign compo-

nents for the e-LIS dictionary, the ontology can be

used as the basis for an ontology-driven dictionary

which forbids constraint violations — see Section 5.

Platform independence of the system was a problem

for MM-DALS; this is an issue the e-LIS team is

taking into account, thus the choice of having the

e-LIS dictionary as a web application. The profile

of the expected user was never analyzed, whereas e-

LIS aims at a dictionary non-experts of LIS can use,

as explained in Section 1. Last but not least, the

MM-DALS team experienced communication prob-

lems among linguists and programmers; the domain

ontology described in this paper has been helpful in

this respect, contributing to make explicit relevant in-

formation and correcting assumptions about the sign

decomposition rules for the e-LIS dictionary.

A bidirectional dictionary for Flemish SL, still be-

ing elaborated, is (Flemish Dictionary, 1999). Users

are presented with images of the body parts involved

in the sign formation; by clicking on a body part, the

user is presented the list of all symbols available for

that part. However, non-experts of the adopted rep-

resentation system, namely SignWriting, cannot eas-

ily use this dictionary. Non-experts are not guided

through the composition process, thus it is easy for

them to choose combinations of sign components

leading to meaningless gestures, that is, not corre-

sponding to any Flemish SL sign. Similar remarks

apply to other on-going transcription-based dictionar-

ies, e.g., see (Vettori, 2006); they are mainly suited to

experts of SL and the adopted transcription system.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first on-

tology developed for a sign language dictionary so far.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In the initial phase of the e-LIS project, the web dic-

tionary from LIS to verbal Italian was intended for ex-

pert signers, only. This restriction is no longer valid;

the users of the web dictionary of e-LIS can also be

non-experts of LIS, willing to learn it. These users do

not know how to compose sign components; as made

clear in Section 2, it is not realistic to expect that these

users will master the transcription system for decom-

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

212

posing and retrieving signs from the web dictionary.

The domain ontology presented in this paper

analyses and represents the rules for the decomposi-

tion of signs of LIS as explained in Sections 3 and

4; it was developed in a top-down manner starting

from (Radutzky, 2001), under the guidance of lin-

guists and deaf users of e-LIS (see Section 2).

The domain ontology already brought the fol-

lowing benefits to the e-LIS project (see Section 5):

it made explicit domain assumptions and facilitated

knowledge sharing in the e-LIS team; it helped in

the requirement analysis and conceptual modelling of

the e-LIS database schema; the decomposition rules

behind the ontology were checked to be consistent.

Moreover, an application ontology, tuned to the data

present in the e-LIS database, is being built on top

of the domain ontology presented here; a query tool

like (Catarci, T. et al., 2004) can then be employed

to assist the users in their sign composition. We are

also working on the visualisation of the composition,

query process and results.

The next milestone of the project will be an evalu-

ation of the ontology-driven dictionary with real users

to assess the usability of the dictionary. More linguis-

tic knowledge of the LIS domain should also be gath-

ered so as to enrich the ontology hence better assist

users in their sign composition (see Section 4), and to

devise good ranking criteria of the visualised results.

As remarked in Section 2, the analysis of the rep-

resentations of SLs in written form is a topic of cur-

rent research per se. At present, this goes beyond the

scope of our work, which is mainly of experimental

nature. After this experimental phase, we can turn to

more foundational work with a deeper analysis of the

written representations of SLs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank for their contributions: J. Anderson,

P. Dongilli, P. Fillottrani, E. Franconi, S. Tessaris,

M. Tomkowicz, C. Vettori, C. Zanoni.

REFERENCES

Catarci, T., Dongilli, P., Di Mascio, T., Franconi, E., San-

tucci, G., and Tessaris, S. (2004). An Ontology Based

Visual Tool for Query Formulation Support. In Pro-

ceedings of the 16th Biennial European Conference on

Artificial Intelligence, ECAI 2004, Valencia, Spain.

E-LIS ontology (2006). URL:

http://elis.eurac.edu/WebSites/ELIS/Doc/

eLISontology.pdf. Last visit: Nov. 2006.

E-LIS project (2004). URL: http://elis.eurac.edu/. Last

visit: Nov. 2006.

Fillottrani, P., Franconi, E., and Tessaris, S. (2006). The

New ICOM Ontology Editor. In International Work-

shop on Description Logics, DL 2006.

Flemish Dictionary (1999). URL:

http://gebaren.ugent.be/visueelzoeken.php?. Last

visit: Nov. 2006.

Garcia, B. (2006). The methodological, linguistic and semi-

ological bases for the elaboration of a written form

of French Sign Language (LSF). In Proceedings of

the Workshop on the Representation and Processing

of Sign Languages, LREC 2006.

Guarino, N. (1998). Formal Ontology in Information Sys-

tems. In Formal Ontology in Information Systems,

FOIS 1998.

Pizzuto, E., Rossini, P., and Russo, T. (2006). Represent-

ing signed languages in written form: questions that

need to be posed. In Proceedings of the Workshop on

the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages,

LREC 2006.

Radutzky, E. (2001). Dizionario bilingue elementare della

lingua italiana dei segni. Kappa.

Sacks, O. (1989). Seeing Voices: a Journey into the World

of the Deaf. Vintage Books. (Italian version: “Vedere

Voci”, Adelphi, 1999).

Stoke, W., Casterline, D., and Croneberg, C. (1965). A dic-

tionary of American sign language on linguistic prin-

ciples. Linstok Press.

Vettori, C., editor (2006). Representation and Processing

of Sign Languages. Lexicographic Matters and Di-

dactic Scenarios. Fifth International Conference on

Language Resources and Evaluation. Post-conference

workshop. Paris: ELRA.

Vettori, C., Streiter, O., and Knapp, J. (2004). From Com-

puter Assisted Language Learning (CALL) to sign

language processing: the design of e-LIS, an elec-

tronic bilingual dictionary of Italian sign language and

Italian. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the Rep-

resentation and Processing of Sign Languages, LREC

2004.

Volterra, V., editor (2004). La lingua dei segni italiana. La

comunicazione visivo-gestuale dei sordi. Il Mulino.

Wilcox, S. (2003). The multimedia dictionary of Ameri-

can sign language: Learning lessons about language,

technology, and business. Sign Language Studies,

3(4):379–392.

AN ONTOLOGY FOR A WEB DICTIONARY OF ITALIAN SIGN LANGUAGE

213