HOW DO GREEK SEARCHERS FORM THEIR WEB QUERIES?

Fotis Lazarinis

Department of Applied Informatics in Management & Finance

Technological Educational Institute, Mesolonghi 30200, Greece

Keywords: Web searching, search engine evaluation, web queries, Greece.

Abstract: This paper presents an initial analysis of a large log of Greek Web queries. The main aim of the study is to

understand how users form their queries. The analysis showed that users include terms of low

discriminatory value and form their queries in various non lemmatised forms. Lower case queries are the

most common case, although several query instances are in upper case. Accent marks are usually left out by

query terms. These conclusions could be utilized by local and worldwide search engines so as to improve

the services offered to the Greek Web community and to users of other morphologically complex natural

languages.

1 INTRODUCTION

Searching the Web is a daily activity of almost all

Internet users. Users form their queries in various

manners and it has been argued that this may depend

on the nationality and cultural background of the

user (Jansen and Spink, 2005). There is a growing

body of research examining the search patterns of

users of predominantly US search engines

(Silverstein et al., 1999; Jansen & Pooch, 2001;

Spink et al., 2002). All these studies focus on

understanding about what topics people search for

and how short or long are their queries. Clearly this

is important, as search engines could be refined

based on their findings. However one of the

limitations of these studies is that they focus mainly

on English Web queries or more general in queries

based on the Latin alphabet. In languages with

different alphabets, like Greek or Russian or Arabic,

additional difficulties could be raised by the way

users form their queries. In these languages

capitalization or diacritics in query terms plays an

important role in relevance of documents (Moukdad,

2004; Bar-Ilan & Gutman, 2005, Lazarinis, 2005;

Lazarinis, in press).

In this study we focus on the Greek language and

try to understand how users form their Web queries.

By identifying the query patterns we will eventually

be able to suggest improvements to search engines

so as to better adapt to and handle Greek queries.

The findings of our statistical analysis may be

directly applicable to other languages with non Latin

alphabets, and noun, adjective and verb declensions.

2 THE STUDY

2.1 Data Collection

The query data were obtained from four Greek

academic institutions. The user search strings of

specific departments are accessible via the Web and

they were analyzed statistically in our study. Data of

the last 12 months (November 2005-October 2006)

were assembled to form our user query data

collection. These queries were redirected to Google

or Yahoo through the local search engines of the

academic departments. Queries were submitted by

members of the Academic staff and by students.

In total, 48 html files were examined containing

211,172 unique queries. 205,474 of these search

strings were in English and the remainder 5,698

queries were in Greek. In some cases the Greek

queries contained English terms as well. In the

following sections we focus on and analyze the

Greek search strings.

2.2 Data Analysis

The html files contained the query strings and some

statistics. We did not analyze or utilize the existing

statistics which focus mainly on the number of times

404

Lazarinis F. (2007).

HOW DO GREEK SEARCHERS FORM THEIR WEB QUERIES?.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Web Interfaces and Applications, pages 404-407

DOI: 10.5220/0001277104040407

Copyright

c

SciTePress

and on the time and the date a query has been

submitted. Motivated by some of our previous work

on the theme of Greek Web retrieval (Lazarinis,

accepted) and the work of Jansen and Spink (2005),

we analyzed the data from a number of different

angles. The data analysis and the conclusions of

each test are presented below.

2.2.1 Query Length

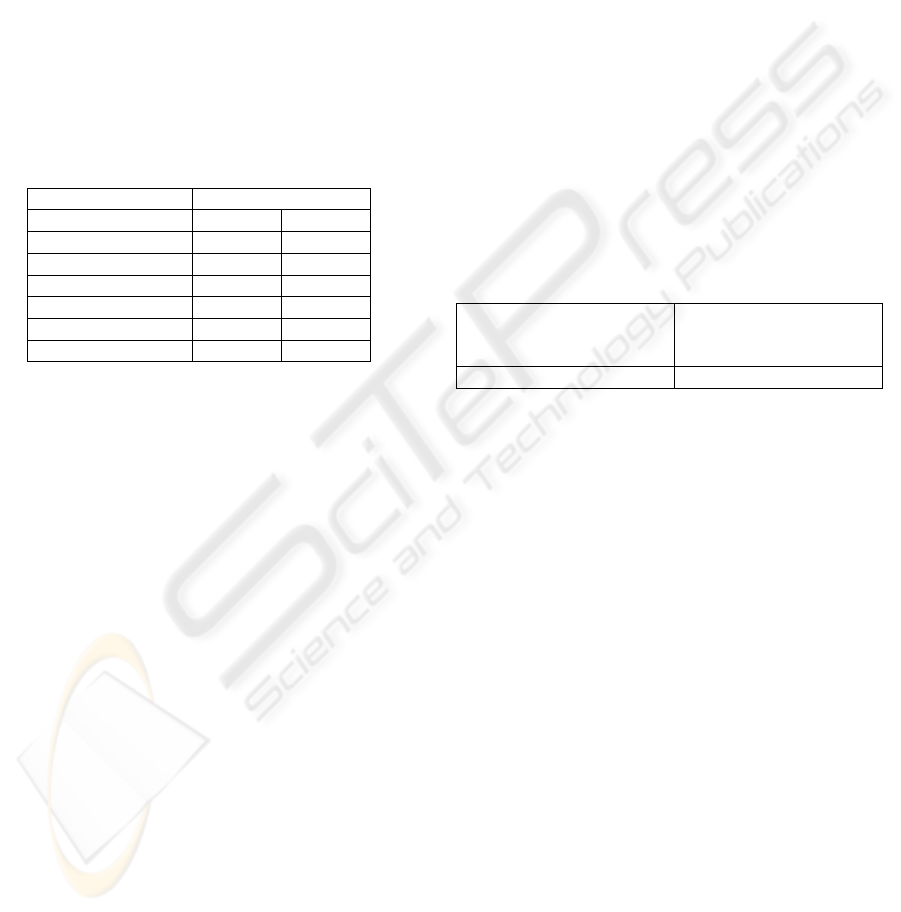

As seen in Table 1, the majority of queries (66.95%)

contain 2 or 3 words which is an indication that

users are aware that 1-word queries are usually too

broad to retrieve reliable results. On average, each of

the 5,698 queries is consisted of approximately 2.47

terms, i.e. 14096 in the 5,698 queries.

Table 1: Lengths of Greek queries.

Number of words Number of queries

n %

1 1,005 17.64

2 2,275 39.93

3 1,540 27.03

4 619 10.86

5 178 3.12

6+ 81 1.42

2.2.2 Lower and Upper Case

Capitalization of query terms is an important factor

in retrieval of Web documents. Lazarinis (submitted)

showed that international search engines like Yahoo,

MSN and even Google, retrieve different numbers of

pages with different precision in lower and upper

case queries. In our sample, 1,028 (18.04%) queries

were in upper case and 4,670 (81.96%) were in

lower case or in title case (i.e. first letter of each

word was capitalized). There was no difference in

the distribution of query lengths in upper and lower

case so as to make any valid inference. However it

seems that upper case queries are finer grained as

they are usually abbreviations or titles or person and

organization names. In these cases retrieval is

probably more effective.

In any case, the percentages of lower and upper

case queries show that although users search using

lower case terms mostly, a considerable number of

queries are in upper case. In English Web searching

there is no differentiation between results in upper

and lower case queries. In Google and Yahoo, for

example, the queries “Ancient Athens” and

“ANCIENT ATHENS” retrieve the same number of

Web documents ranked identically. However, in

Greek the queries “Αρχαία Αθήνα” and “ΑΡΧΑΙΑ

ΑΘΗΝΑ” retrieve different numbers of Web pages

and therefore it is up to the Greek users to run the

queries in both forms to get the maximum number of

relevant documents.

2.2.3 Accent Marks

The Greek language is a morphologically complex

language compared to English and to some of the

European languages which are based on the Latin

alphabet. Modern Greek words use accent marks and

umlaut in vowels in lower case letters. In capital

letters accent marks are not regularly used.

It has been reported that when diacritics are

absent, precision drops significantly in Web

searching (Lazarinis, accepted). Table 2 illustrates

that 46.21% of the lower case queries contain at

least one word without accent marks and that more

than 1/4 of the query sample are typed entirely

without accent marks. 5,251 out of the total 11,700

(44.88%) words of the lower case queries had no

diacritics.

Table 2: Number of user queries without diacritics.

Queries with all words

without diacritics

Queries with at least

one word without

diacritics

1,542 – 27.06% 2,633 – 46.21%

The problem is more serious in the case of

umlaut. By searching the query sample we found 6

variations of the word “Ευρωπαϊκή” (European). 5

of these variations were typed without umlaut. This

is maybe to user lack of knowledge of how to input

umlaut in vowels. In any case it influences

negatively the recall and relevance of pages. For

instance, in Yahoo the word “Ευρωπαϊκή” retrieves

1,250,000 pages, the term “Ευρωπαική” 33,400 and

the term “Ευρωπαικη” 32,300 pages. In the latter

two queries relevance in the first 10 results is

significantly lower than the normal form. Google

has identified this difference and retrieves the same

pages in all three variations.

2.2.4 Lemmatised Form

The query “Bookshop New York” retrieves pages

having as matching terms the words “Bookshops”,

“Book”, “Books” and “Bookstore” in Google. In

other words synonyms and lemmas of a word are

matched to the query terms to help the searcher

locate more relevant pages.

Nouns, adjectives, verbs and even first names

have conjugations in Greek (nominative, genitive,

etc). Lemmatization involves the reduction of words

to their respective headwords (i.e. lemmas). For

HOW DO GREEK SEARCHERS FORM THEIR WEB QUERIES?

405

example, the terms “speaks” and “speaking”,

resulting from a combination of a sole root with two

different suffixes (“s” and “ing”), are brought back

to the same lemma “speak”.

With the aid of a dictionary we calculated that

4,135 lower case queries were not in lemmatised

form (Table 3). The percentage is lower in upper

case queries (31.03%) as most of these terms are

abbreviations or person and organization names (see

Table 3). Subtle differences in queries (e.g.

“Πανεπιστήμιο Αθήνας”, “Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών” –

University of Athens) are capable of differentiating

the retrieved pages in Google, Yahoo and in the

other international and even national search engines,

which supposedly have a better understanding of the

Greek language.

Table 3: Number of non lemmatized queries.

Lower case queries in

non lemmatised form

Upper case queries in

non lemmatised form

4,135 – 88.54% 319 – 31.03%

Lemmatization would be quite helpful in Greek

Web searching since most of the queries and

obviously Web pages are not in lemmatised form

and their matching is apparently not possible.

2.2.5 Stopwords

Stopwords are the terms which appear too frequently

in documents and thus their discriminatory value is

low (van Rijsbergen, 1979). Elimination of

stopwords is one of the first stages in typical

information retrieval systems. In English Web

searching stopwords are removed or they do not

influence the retrieval process significantly.

Stopword lists have been constructed for most of the

major European languages (see http://snowball.

tartarus.org for example) and they could be utilized

by search engines. Such a listing does not exist for

the Greek language. Usual candidates of the

stopword list are articles, prepositions and

conjunctions (Baeza-Yates & Ribeiro-Neto, 1999).

Using all 5,698 lower and upper case queries we

identified the articles, prepositions and conjunctions

existing in our query collection. Such common

words exist in 1,516 queries. That is 26.61% of the

queries contain common words. These words

occurred 2,032 times within these 1,516 queries.

Thus they account for the 14.42% of the total words

of the Greek queries.

These statistics indicate that users do utilize

common words in their queries and therefore the

construction of a Greek stopword list and its

application to Web retrieval should be further

studied.

2.2.6 Other Issues

Although the analysis of the data is still in progress,

the most important issues were discussed above. A

number of other issues were also identified by

observing the user queries but they have not been

thoroughly examined as yet.

A number of queries in the English part

contained the string “www” or were in a semi url

form. For instance, a user typed the query “travel to

Greece.gr”. This is an indication that some users are

not competent in search engine usage. Proper

training or presentation of proper examples on the

search engine’s page could help users work out their

misconceptions.

By inspecting the first 100 queries of the sample

we located 3 spelling errors. We run these queries in

Google and we got either no results or pages with

the same spelling errors as in the query. International

search engines aid English users even in spelling

errors with “Did you mean” tips. For instance,

Yahoo presents the message “Did you mean:

confidentiality” if a user types the word

“confidentiallity” in its searching box.

In 12 Greek queries the “*” wildcard was used at

the end of the query. As known, users get no

additional results if they use wildcards. Additionally,

the wildcard was not properly used as a space was

included between the wildcard and the last word.

This observation, along with the inclusion of “www”

in the queries, is an indication that a few search

engine users are confused and therefore training is

needed.

“GreekEnglish” is a term shared among Greek

Internet users. It refers to the typing of Greek words

using English characters. For example, the word

“Athina” in GreekEnglish, is the word “Αθήνα” in

Greek and “Athens” in English. GreekEnglish

originates from the time Greek were not supported

in some operating systems or in e-mail clients and it

was invented as a communication means so as to

assure readability. Several users still follow this

logic. We observed several instances of

GreekEnglish queries in our sample. However, it

cannot be decided whether it was a conscious action

or this behavior results, again, from user

misconceptions about the ability to use or not Greek

characters in searching. Advanced options such as

site or file specification were sporadically detected.

However, we cannot derive valid conclusions from

this finding since queries are submitted to Google

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

406

and Yahoo through the local search engine. So

advanced options are not immediately visible and

available to these users.

3 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents the initial analysis of a large

query log. Although the analysis is not complete as

yet some important findings resulted from this study.

It is easily understood that Greek users include

common words and form their Web queries in

various declensions. Lower case queries are the most

common case, although several query instances were

in upper case. Accent marks are usually left out. By

observing the queries we realized that, as

anticipated, users do some spelling errors and they

erroneously use wildcards and other not proper

characters or strings.

These facts affect negatively Web searching

using Greek terms. Some of these problems have

been effectively dealt by Google. However the

techniques which could substantially reduce user

effort and have already been applied in English

searching are not adapted to the Greek language.

Probably similar problems are faced by other non

Latin users. Search engines should try to value these

natural languages. One way to achieve this is

through the user queries.

REFERENCES

Baeza-Yates, R., & Ribeiro-Neto, B., 1999. Modern

Information Retrieval, Addison Wesley, ACM Press.

New York.

Bar-Ilan, J., Gutman, T., 2005. How do search engines

respond to some non English queries? Journal of

Information Science, 31(1), 13–28.

Jansen, B. J., Pooch, U., 2001. Web user studies: a review

and framework for future work. Journal of the

American Society of Information Science and

Technology, 52(3), 235–246.

Jansen, B., Spink, A., 2005. An analysis of Web searching

by European AlltheWeb.com users. Information

Processing and Management, 41, 361–381.

Lazarinis, F., 2005. Do search engines understand Greek

or user requests “sound Greek” to them? In Open

Source Web Information Retrieval Workshop in

conjunction with IEEE/WIC/ACM International

Conference on Web Intelligence & Intelligent Agent

Technology, pp. 43-46.

Lazarinis, F., in press. Evaluating the searching

capabilities of Greek e-commerce Web sites. Online

Information Review Journal.

Lazarinis, F., accepted. Web retrieval systems and the

Greek language: Do they have an understanding?

Journal of Information Science.

Moukdad, H., 2004. Lost in Cyberspace: How do search

engines handle Arabic queries? In Proceedings of the

32nd Annual Conference of the Canadian Association

for Information Science, Winnipeg.

Silverstein, C., Henzinger, M., Marais, H., Moricz, M.,

1999. Analysis of a very large Web search engine

query log. SIGIR Forum, 33(1), 6–12.

Spink, A., Jansen, B. J., Wolfram, D., Saracevic, T., 2002.

From e-sex to e-commerce: Web search changes.

IEEE Computer, 35(3), 107–111.

van Rijsbergen, C.J., 1979. Information Retrieval,

Butterworths. London, 2

nd

edition.

HOW DO GREEK SEARCHERS FORM THEIR WEB QUERIES?

407