ACCEPTANCE BY THE USERS OF SERVICES INTEGRATED IN

THE HOME ENVIRONMENT

Michele Cornacchia, Vittorio Baroncini

Fondazione Ugo Bordoni, Via Baldassarre Castiglione, 59 - 00142, Rome, Italy

Stefano Livi

Facoltà di Psicologia 2, Università degli Studi “La Sapienza”, Via dei Marsi, 78 – 00185, Rome, Italy

Keywords: Acceptance, assessment, controlled environment, ease of use, end users, evaluation, home control, home

networking, home services, integration of ICT, intention of use, interoperability, laboratory home platform,

laboratory trial, perceived usefulness, predictive model of user, services integration, usability.

Abstract: Whether or not ICT represents the most important vehicle to transform the society seems to be out of

discussion. The point of interest diverts from how people do really feel with these services and from the way

they perceive the advantages as acceptable to improve the quality of life and work. It is matter of fact that

the technical innovation is characterized by a certain risk, the problem of how to implement the technology

for sure and, ahead of this phase, the problem of predicting its influence on the social, working and private

life in view of the high costs effort to produce. This study applies a predictive model for the acceptance to a

services integrated home environment properly set-up in a special laboratory. A class of users was selected

from the employees of the company which hosted the trial in order to participate at the evaluation sessions.

The tasks were designed to point out the main innovative features of the services presented. The

questionnaires were suitably designed and submitted to collect the end-users opinions. The analysis was

carried out to assess the performance by the side of the real users and to predict their intentions of use.

1 INTRODUCTION

The study here presented is part of the work carried

out in order to investigate the user perception of the

ePerSpace (EPS, IST Project N° 506775) personal

services for the Home and Everywhere that were set

up at the laboratories of a big telephone company,

partner in the project.

The general aim was to measure the quality of

the delivered services, by verifying the usefulness

and ease of use as perceived by the real users, then

the amount of added value provided by each service,

even in a high technology reproduced environment.

The basic references given by the Unified Theory of

Acceptance and Use of Technology (Venkatesh et

al, 2003) were applied to define a model to forecast

the user acceptance (intention as predictor of usage)

and arrange the scales (questionnaires) to measure

the performance constructs.

2 THE ACCEPTANCE MODEL

Information Technology represents today a primary

way of transforming society but each application is

assumed to achieve specific benefits. The new

technologies actually can be applied to achieve a

wide variety of benefits (e.g. improve quality of the

life, of the work, etc.) and have influences in the

organisational change (e.g. improve productivity,

enhance work, effectiveness, etc.).

Because any kind of technical innovation is

characterized by a certain risk, there is the problem

of how to implement the technology and, ahead of

this phase, the problem of predict its influence (in a

short: “success or failure?”) in view of the high costs

effort to produce. If we look at some evidence about

the success or failure rates of information

technology projects, we firstly see that is very

difficult to attain data as the high complexity and

variability of the whole socio-technical system to

75

Cornacchia M., Baroncini V. and Livi S. (2007).

ACCEPTANCE BY THE USERS OF SERVICES INTEGRATED IN THE HOME ENVIRONMENT.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies - Web Interfaces and Applications, pages 75-82

DOI: 10.5220/0001280600750082

Copyright

c

SciTePress

consider (Eason, 1988). The ordinary criticisms are

that the technology is being oversold (Cornacchia,

2003) and that it is regularly subject of changes

within short periods of time. Nevertheless, there are

some studies, named in the following, that give an

indication of the scale of the problem and the nature

of the possible outcomes. These studies are aiming

to support those organisations that accept risky

investment decisions for instance in order to get a

better competitive position. Many examples of the

emerging information technologies have been

publicized with consistent investment market

projections, but they remain strongly fastened by a

broad alone of uncertainty as for their effectiveness.

At the last, the most important questions rising up

the mind of the decision makers are about which of

these technologies will succeed and what the useful

applications have to be.

In the history the relevant literature describes the

development of several models of technology

acceptance (by the users) and many extensions to the

basic constructs (Malhotra & Galletta, 1999;

Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), mostly built with the

behavioural elements (Ajzen, 1996) of who is

forming an intention to act (Bandura, 1986) and the

inclusions of some kinds of constraints (limited

ability, learning and usage (Bagozzi et al, 1992),

time, environmental, organisational, unconscious

habits, and so on) which influence the individuals

actions (Compeau et al, 1999; Pierro et al, 2003).

Information technology acceptance research has

applied many competing models, each one with

different sets and very often overlapping of the

acceptance determinants (Davis, 1989). In their

paper Venkatesh and colleagues (2003) compared

eight competing models that were applied in order to

understand and predict user acceptance: Theory of

Reasoned Action (TRA), Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM), Motivational Model (MM), Theory

of Planned Behavior (TPB), Combined TAM and

TPB (C-TAM-TPB), Model of PC Utilization

(MPCU), Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT), Social

Cognitive Theory (SCT). Those models were

originated from different disciplines mostly

connected with the behaviour prediction (Ajzen &

Fishbein, 1980) or specialized for the technology

use, from psychology to information system

literature. As a result, research on user acceptance

appear to be fragmented in different methods and

measures (Venkatesh & Davis, 1995).

For this reason the authors empirically compared

those concepts in order to formulate a Unified

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model

(UTAUT) with four core determinants of intention

and usage, and up to four moderators of key

relationships (Figure 1): Performance Expectancy,

Effort expectancy, Social Influence and Facilitating

Conditions as well as other moderators variables

(such as Gender, Age, Experience and Voluntariness

of Use).

Figure 1: Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

model (UTAUT) from (Venkatesh et al, 2003).

Applied to the tested system, the Performance

Expectancy is defined as the believes that using the

new services will help him to attain gains in the

behavioural objectives. For the ePerSpace aim, this

variable will be made operative through the

Perceived Usefulness construct, relative advantage

of using the innovation compared to its precursor,

and outcome expectations.

The Effort Expectancy, defined as the degree of

ease associated with the use of the new system, has

as operative constructs the general perceived ease of

use as well as the perceived complexity of the

system.

The Social Influence, defined as the individual

perception of how individual social network believes

that he or she should use the new system, has as

operatives constructs Subjective norms, Social

factors and Social image and Identity similarity.

Finally, the Facilitating Conditions, are

represented by construct by Perceived Behavioral

control, general facilitating conditions (such as

objective environment factors) and compatibility

with existing values and experience of the potential

adopters.

One of the basic concept underlying the model of

user acceptance states that, in the domain of

“consuming the emerging technology”, the actual

use of information technology is influenced by the

intention to use and by the individual reactions to

using. And so, the greater are the positive reactions,

the greater is the intention and therefore the

possibility to engage in the use.

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

76

3 METHOD

3.1 Measurement Scales

The measurements scales of the acceptance applied

to the design of the questionnaire instrument are

mentioned in the following. All the scales were

tested and successfully used (high degree of

adaptability, high Cronbach alpha to denote the

consistence of the constructs, high variance

explained to denote independency of variables) in

several contexts or technological environments and

for different classes of users.

It is nevertheless important to call attention to the

fact that the questionnaires were adapted to the tasks

and that each subject participating to the evaluation

got first confidence with the innovating technology.

Said that, each questionnaire was referred to a

specific task and there were included, when

required, additional lines to purposely measure the

usability aspects of some significance (SUMI,

1998). Therefore, besides the central constructs of

the acceptance, the questionnaires included also

other high reliability scales, either for usability

(namely on efficiency, affect and control) either for

the identity-similarity or motivations (Perugini et al,

2000).

The results by the submission of such scales in

the evaluation provided the empirical evidence of a

large effect of personal identity on different

behavioural intentions. As for the home services

tested, the consumer behaviours may had a symbolic

meaning beyond their practical and objective

features and consequences. For example, buying a

certain equipment/system could have been an

associated behaviour with an image of “idealized

people” or with the “prototype” of the persons who

perform these behaviours.

The constructs used in the assessment were:

Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social

Influence, Facilitating conditions, Attitudes toward

Using Technology, Attitudes (towards home

environment solutions), Intentions, Identity-

Similarity, Usability.

They corresponded to the questionnaire sections:

A - Perceived Usefulness in the home environment

B.1 - Perceived ease of use

B.2 - Complexity

B.3 - Ease of use

C.2 - Social factors

C.3 - Image

D.1 - Perceived behavioural control

D.2 - Facilitating conditions

D.3 - Compatibility

E.1 - Attitudes towards behaviour

E.2 – Intrinsic motivation

E.3 – Affect towards use

E.4 – Affect

F - Attitudes towards EPS solutions

G – Intentions

3.2 The Home Services Evaluated

The home environment services evaluated by the

users were selected from those that were set-up

within the Home Platform Portal. An outlook of the

services portal made available is shown in the

following Figure 2.

Figure 2: The home page to access the ePerSpace services

at Home and Everywhere.

The Home platform services available in the

portal are exposed in the Table 1.

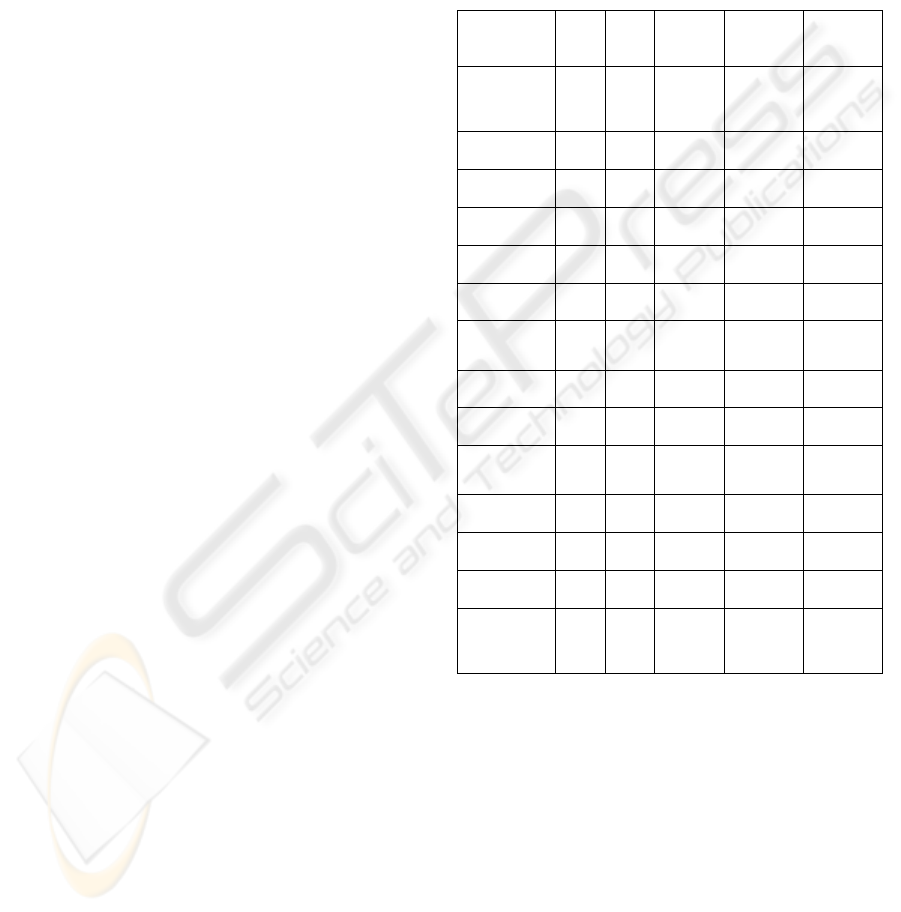

Table 1: Home platform services of ePerSpace.

HOME

PLATFORM

SERVICE

Indoor elements

Outdoor

elements

Appliances,

actuators and

white

appliances

management

Residential Gateway,

home automation

networks, home devices

and white appliances,

personal devices for

service interface

(PDA/smart phone/PC/TV)

Service

and

network

provider

Alarms

Handling

Residential Gateway,

home automation

networks, personal devices

for service interface

(PDA/smart

phone/PC/TV), network

cameras

Service and

network

provider

Access control Residential Gateway,

RFID reader; RFID

personal cards, home

automation network, smart

phone/PC/TV

Service and

network

provider

ACCEPTANCE BY THE USERS OF SERVICES INTEGRATED IN THE HOME ENVIRONMENT

77

The control of the automated home appliances

and devices includes the management of:

- Lonwork actuators and sensors over twisted pair:

lights, water valve, blinds, canopies, door lock,

fire/gas/water detectors, etc.

- Lonwork white appliances over power line: oven

and washing machine.

- Actuators and sensors: lights and small motors

attached to a demo panel.

- Network cameras.

3.3 The Tasks

A set of tasks was properly designed for the class of

users profiled for the trial and the services to

evaluate. The services were accessed by the user

from any PC or PDA wired or wirelessly connected

to the LAN of the home. In both cases, the user

started the browser of the access terminal to initially

authenticate him/herself by username and password.

After that, the user was admitted to the home portal

and enabled to select from the list of the personal

services.

In case of being using the web access, a map of

the house displayed icons representing the home

appliances that can be actuated, as well as its current

state (i.e., on/off). At the user click on each icon a

menu of the possible actions appeared. For example,

in the case of a light, currently on, the user was

offered to switch it off and adjust the light intensity.

In case of using the PDA access, instead of a map of

the house, the user found a list showing the rooms in

the house. At the user click on one of the rooms, the

list of automated devices to be controlled in that

room displayed. The running was similar to the web

access, but the graphical interface was more simple

to adjust to the limited screen size.

3.4 Set-Up of the Test Bed

All the HAN of the test-bed were connected to the

RG (Residential Gateway) which run an OSGi

(Open Services Gateway initiative) framework over

which the home platform services are managed and

activated. A Personal Computer or Laptop or a

Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), inside the house,

were used either to access the web interface of the

services and also to provide the I/O for the tasks

planned to be accomplished by the users in the

assessment. The PDA was connected to the HAN via

WiFi in the house for the demonstration. A Set Top

Box (STB) was connected to the TV set and could

run also home environment services, controlled by

the RG Middleware.

Basically the automated control for the house

domestic devices from the PC in web interface

services of the Home Platform were evaluated. The

user accessed the options from a list of services

directly through the main page. The procedure to

carry out the evaluation followed a prearranged

scheme. Each subject was received in front of the

house door, informed about the overall session and

the services to be evaluated by means of

questionnaires. The questionnaires were arranged in

a labelled sequence, then submitted to the subject.

About 60 questions over the total amount of 193

were answered by each subject in the section of the

local services for the home (Figure 3).

Figure 3: “Home Control” sub-menu.

The evaluation process took place in two weeks

in total. The integration work lasted 6 months. The

test bed used for the user evaluation gave a

configuration and outlook of a real flat (Home).

3.5 The Users Profile

A two steps selection of final 40 users followed

some general criteria in order the final class of

subjects could be the most homogeneous possible

and provide consistent values of judgements.

The subjects selected for this evaluation were

chosen among the employees of the company

hosting the trial, as close as possible to an ideal type

of potential user, open minded enough towards ICT

solutions (neither too much enthusiastic neither to

much unwilling) and on an average skilled in using

electronic digital devices (e.g. the PC or other home

familiar devices).

The first step in the definition of a class of users

was mainly a rough skimming from a initial set of

about 70 individuals, preliminarily contacted in

order to be certain that:

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

78

1. the subjects characteristics were close to the

home services requirements of use;

2. the essential skills and the basic attitudes

towards ICT were not unacceptable;

3. the subjects were volunteers.

The second step was a selection of the final 40

users, among the several items relating about each

individual, to check whether:

1. the final group were sufficiently represent

males and females;

2. the age range (at least) were as narrow as

significant to the statistics to apply;

3. the availability to effectively participate to the

evaluation sessions were an actual statement.

The emerging final profile shows:

1. a proportion of frequencies about the 23% for

females while the 77% for males;

2. evident age crowding in the range 30-39 years,

3. equal occurrence of married and single

individuals;

4. medium-high level of education;

5. mostly technicians and engineers (respectively

70% and 15%);

6. high experience accrued with ordinary IT

technologies (PC, Email, Mobile, etc.);

7. proximity to household equipment with

communication means.

The users participating to the evaluation went

through an introduction of the Project and a training

session in order for them to use the system almost

without assistance in order to obtain valuable and

not-biased information from the questionnaires.

3.6 The Data Analysis

The questionnaires were coded and the data properly

wrapped up to be analysed by means of the SPSS

(Statistical Package for Social Science 13.0). Three

main groups of analyses were generated as output:

1. descriptive statistics for all cases and outliers

identification; the data were grouped in the way

that the scores of the home services appeared, for

each aspect of the Acceptance.

2. correlation study for the Home services relative

to the dependant variable “attitudes towards

behavior”.

3. extended correlation study of the service Home

Control in relation to the dependant variables

“attitudes towards EPS solutions” and

“intentions”.

4 RESULTS

The descriptive statistics (median, confidence

interval within ±σ, outlier rejection interval > ±2σ)

were shortly assembled in the 14 lines of Table 2, as

many as the cases were for the Home Control Panel

and the home services through it accessed.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for the Home Services

accessed through the Home Control Panel.

HOME

CONTRO

L PANEL

min

ma

x

averag

e

standard

deviation

outliers

Perceived

Usefulness

in the home

environment

1.0

0

5.50 2.81 1.08 0

Perceived

ease of use

1.0

0

5.00 2.24 .88 1>max

Complexity

4.0

0

7.00 5.74 .86 0

Ease of use

1.0

0

5.00 1.88 .84 1>max

Social

factors

1.0

0

7.00 3.03 1.69 0

Image

1.0

0

7.00 3.33 1.64 0

Perceived

behavioural

control

2.0

0

6.33 3.56 .81

1<min,

2>max

Facilitating

conditions

1.0

0

7.00 4.17 1.77 0

Compatibilit

y

1.0

0

6.00 2.38 1.21 0

Attitudes

towards

behaviour

2.0

0

7.00 5.79 1.30 2<min

Intrinsic

motivation

1.0

0

7.00 2.56 1.27 2>max

Affect

towards use

2.0

0

7.00 5.54 1.34 0

Affect

2.5

0

7.00 4.63 .79 1>max

Attitudes

towards

EPS

solutions

2.5

0

7.00 5.13 .93

2<min,

2>max

4.1 Frequencies

The analysis of the frequencies gathered pointed out

that from a broad point of view the services were

well accepted by the users, as innovative for the

home and access from the elsewhere. The variables

used to define the constructs of the acceptance

model, all showed a definite tendency in positively

comparing the ICT solutions presented in the test-

bed with the already available personal services that

can be seen as a clear advantage and concrete

expectation for the home services to improve the life

style of its users.

ACCEPTANCE BY THE USERS OF SERVICES INTEGRATED IN THE HOME ENVIRONMENT

79

This important result was first attained by the

Perceived Usefulness, and then it was supported by

the plain scores gathered by Effort Expectancy (i.e.

very high of ease to learning and low perception of

complexity) and Social Influence (i.e. the family

view coherent and close to a doable real use). At

last, the external conditions tested were compatible

with the life style of the subjects and as a matter of

fact not opposed to the potential adoption, as well as

the wide-ranging attitudes towards the new home

solutions.

4.2 Correlation

The Pearson correlations were computed to look for

significant linear links between the variables of the

Predictive Model of the Acceptance, i.e. for the

Home Service and the dependent variable (positive)

“Attitudes towards behavior” (item of section E1 in

the questionnaire), as resulted in Table 3 analysis.

Table 3: Attitudes towards the new solutions for the Home

Control.

Valid cases

Attitudes towards

solutions for HOME

CONTROL

Perceived Usefulness in

Home Environment

.35(*)

Perceived ease of use .17

Complexity -.19

Ease of use .06

Social factors

.42(**)

Image -.05

Perceived behavior control -.03

Facilitating conditions .05

Compatibility

.46(**)

Attitudes towards behavior

.53(**)

Intrinsic Motivation

.42(**)

Affect towards Use .30

Affect -.01

*. Correlation significant at the degree of 0,05 (2-tails).

**. Correlation significant at the degree of 0,01 (2-tails).

As given in the Table 3, all values in bold and

with one/two asterisks indicate the presence of a

high/higher degree of correlation between the

variables. Having a look to the links in the picture of

the predictive model of acceptance, it means that, for

the home services, there were good probabilities that

the positive attitude of a user-consumer were

influenced by those variables. Taken for example the

Home Control “Perceived Usefulness: effectiveness

in home activities”, it can be said that: either “the

greater is the effectiveness in the home activities the

greater is this influence on the “positive attitude

towards solutions”, or it can be said “the significant

Pearson correlation provides evidence that the

variable “perceived usefulness” stimulates the

perception of positive attitude towards solutions”.

4.3 Extended Correlation

The Pearson correlations were computed in order to

look for significant linear links between the

variables of the Predictive Model of the Acceptance,

for the Home Control alone, and the two dependent

variables “Attitudes towards EPS solutions” and

“Intentions” (respectively sections F and G of the

questionnaire). The results are shortened in Table 4.

Table 4: Home Control correlations with “Attitudes

towards EPS solutions” and “Intentions”.

HOME CONTROL

Attitudes

towards EPS

solutions

Intentio

ns

Perceived Usefulness in the

Home Environment

.45(**) .33(*)

Perceived ease of use .31 .16

Complexity -.27 -.30

Ease of use

.35(*) .33(*)

Subjective norms

.33(*) .40(*)

Social factors

.41(*) .64(**)

Image .24 .31

Perceived behavioural

control

.29 .13

Facilitating conditions .14 .07

Compatibility

.54(**) .47(**)

Attitudes towards behaviour

.62(**) .43(**)

Intrinsic Motivation

.63(**) .45(**)

Affect towards Use

.39(*)

.12

Affect .29 .30

*. Correlation significant at the degree of 0,05 (2-tails).

**. Correlation significant at the degree of 0,01 (2-tails).

The Home Control extended study was based on

the choice of a different (but close to the previous

set) couple of dependent variables to be used to

compute the Pearson correlations.

As given in the Table 4, all values in bold and

with one/two asterisks indicate the presence of a

high/higher degree of correlation between the

variables. Always having a look to the links figured

in the predictive model of acceptance, it mean that,

for the Home Control service, the “perception of

having intention to use” of the subjects was even

more demonstrated to be influenced.

The main difference from the other table is in the

availability of the “intention” as direct dependant

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

80

variable. This availability makes the accuracy of the

measure higher. As seen by simply comparing the

columns of the “attitudes towards EPS solutions” in

both Table 3 and Table 4, more accuracy made

possible the detection of more correlations.

As concerning the Home Control service, the

interpretation of the correlations is the same than in

the previous table. Taken for example the Home

Control “Perceived Usefulness: effectiveness in

home activities”, it can be said that: either “the

greater is the effectiveness in the home activities the

greater is this influence on the “intention of using”,

or it can be said “the significant Pearson correlation

provide evidence that the variable “perceived

usefulness” stimulates the perception of having

intention to use”. The Table 4 also provide a direct

read of the correlation to the intention in the second

column.

4.4 Gender Differences

In order to evaluate the differences between Male

and Female perception of the Home Control Panel,

was compared the mean of each sample and

performed an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to

verify if those differences were statistically

significant.

Results showed that, overall, male and female

perceived user acceptance in the same way for

almost all the dimensions explored. The only

noteworthy exception was pointed out for the

“Perceived Usefulness in The Home Environment”,

where females, differently from males, stated that

using the Home Control system would enhance their

job performance (

F(1,37)=6.10; p<.05).

In the following Table 5 there are the results for

the mentioned variable.

Table 5: Gender differences for the Perceived Usefulness

in the Home Environment.

Perceived Usefulness in the Home

Environment HOME CONTROL PANEL

Mean N

Standard

deviation

Male

2.62 30 .98

Mean N

Standard

deviation

Female

3.56 9 1.08

Mean N

Standard

deviation

Total

2.83 39 1.07

ANOVA: F(1,37)=6.10; p=.02

5 CONCLUSIONS

The new home services as provided in the trial were

on the whole accessed by the subjects with high

curiosity and interest. The adoption of a controlled

interactive session to present the services and their

innovative features was able to give to each single

participant the time necessary to understand and

quickly build a personal judge about.

Then the repeated sequence task-questionnaire to

gather data demonstrated to be appropriate in

catching the impulsive ideas about the added values

given by each service in comparison with the actual

home possibilities, as well as the possible adoption

in the own life. This is an excellent consequence of

the methodology proposed for the evaluation, then

proved by the reliable data obtained.

As for the acceptance items, this is a composite

variable that can be carefully expressed by

combinations of different results (and different

constructs).

Therefore, by considering the “perceived

usefulness” (Questionnaire Section A), the users

class received a positive feeling from the services.

This result is strongly powered by looking at the

values of the Questionnaire Sections B.1, B.2, B.3,

which indicate the clear easiness to operate and the

low perception of underneath complexity, even not

really so (this is and excellent result from the

usability point of view, better evident for the Home

Control).

The social factors (Questionnaire Sections C.2,

C.3) confirmed how the subjects view was also

shareable with the family and the close neigh

borough.

The facilitating condition “having the

resources/knowledge necessary to use the system”

(Questionnaire Sections D.1, D.2) resulted about

neutrally considered in relation with the acceptance,

while it was very encouraging the perception of the

“compatibility” (Questionnaire Section D.3),

actually close to the idea of lifestyle at home.

The rest of the items in the questionnaire directly

checked the attitudes of the subjects towards both

the service idea and the actual usage possibility at

home. The resultant Questionnaire Sections E.1, E.2,

E.3, E.4 scored high positive values, indicating that

there were clear intrinsic motivations in the thought

of acquiring these services for the home.

Finally, the last variable (Questionnaire Section

F) of “attitudes towards EPS solutions” in a straight

line confirmed that the users should be willing to

introduce the new solutions at home, as they were

desirable, important, useful and agreeable.

ACCEPTANCE BY THE USERS OF SERVICES INTEGRATED IN THE HOME ENVIRONMENT

81

The ANOVA applied to find differences of

behaviour between males and females, pointed out

no statistical differences except one: the females

perceived differently the “usefulness at home” of the

services.

The analysis on the data gathered of course

didn’t investigate the cause of this “social”

difference, nonetheless, it is spontaneous to think at

the actual different condition of the women at home

in different countries and the different perception of

“the usual staying at home” they may have with

respect to the men.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to the Spanish partners of the

ePerSpace Project without whom the experimental

sessions with the users couldn’t have taken place.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., 1980. Understanding attitudes and

predicting social behaviour, Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Bagozzi, R. P., Davis, F. D., & Warshaw, P. R., 1992.

Development and test of a theory of technological

learning and usage, Human Relations, 45(7), 660-686.

Bandura, A., 1986. Social Foundation of Thought and

Action: A Social Cognitive Theory, Prentice Hall,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Compeau, D. R., Higgins, C. A., and Huff, S., 1999.

Social Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions to

Computing Technology: a Longitudinal Study, MIS

Quarterly (23:1), pp. 145-158.

Cornacchia, M., 2003. Usability, a way to distinguish from

the good, the bad, and the irrelevant in the web, Cost

269, Conference Proceedings, Media Centre Lume,

University of Art and Design, Helsinki (Finland),

pp.159-163, September.

Davis, F. D., 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease

of use, and user acceptance of Information

Technology, MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340,

September.

Eason, K., 1988. Information technology and

organisational change, Taylor & Francis.

Malhotra, Y., Galletta, D. F., 1999. Extending the

Technology Acceptance Model to Account for Social

Influence: Theoretical Bases and Empirical

Validation, Proceedings of the 32

th

Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences (IEEE

99).

Perugini, M., Gallucci, M., Livi, S., 2000. Looking for a

Simple Big Five Factorial Structure in the Domain of

Adjectives, European Journal of Psychological

Assessment, Vol.16, Issue 2, pp. 87-97.

Pierro, A., Mannetti, M., Livi, S., 2003. Self-Identity and

the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Prediction of

Health Behavior and Leisure Activity, Self and

Identity, 2: 47-60.

SUMI, 1998. Software Usability Measurements Inventory

(7.38), Human Factors Research Group, Cork, Ireland.

Taylor S. and Todd, P. A., 1995. Assessing IT usage: The

role of prior experience, MIS Quarterly (19:2), pp.

561-570.

Thompson, R. L., Higgins, C. A., and Howell, J. M., 1991.

Personal computing: towards a conceptual model of

utilisation, MIS Quarterly (15:1), pp. 124-143.

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F. D., 1995. Measuring User

Acceptance of Emerging Technologies: An Assessment

of Possible Method Biases, Proceedings of the 28th

Annual Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences (IEEE 95).

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F. D., 2000. A theoretical extension

of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal

field studies. Management Science, (46:2), 186-204.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., Davis, F. D.,

2003. User Acceptance of Information Technology:

Toward a Unified View, MIS Quarterly vol. 27 No. 3,

pp. 425-478, September.

WEBIST 2007 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

82