ARE MEDIA CUES REALLY A KEY DRIVER TOWARDS TRUST

IN BUSINESS TO CONSUMER E-COMMERCE

Khalid Al-Diri and Dave Hobbs

Informatics school, Bradford University, Bradford, UK

Rami Qahwaji

Informatics school, Bradford University, Bradford, UK

Keywords: E-Commerce, E-Vendor, Internet, Online Shopping, Saudi Arabia.

Abstract: E-commerce B2C yet suffers from consumers’ lack of trust, and most of the research in e-commerce field

focuses on how to build trust through cues that appeal to pursue consumers to do on-line purchasing. Since

the nature of the Internet is lack of interpersonal exchanges that enhance trust behaviour, in this study we

compared on-line consumers’ initial trust on four on-line vendors with the interpersonal cues of a person

representing customer supports (Western photo, Saudi photo, Western video clip) and without photo

through an extensive lab experiment. We found that the photograph and the video clip enhanced the initial

trust than no photo and that the effect of the culture was stronger with Saudi than Western photo.

Nevertheless, we presented many results that benefit the academic and the practitioner respectively.

1 INTRODUCTION

Commerce is one of the oldest activities that men

have known. With the growing popularity of the

Internet, it is only natural that commerce found its

way into this medium. This kind of commerce where

business is carried out using electronic means is

referred to as "electronic commerce or "e-

commerce" (EC). EC allows regional businesses and

economies to be less local and more global in

keeping with long-term trends toward market

liberalization and reduces trade barriers.

Accordingly, EC is considered to be an unavoidable

alternative for companies of the 21st century(Adam,

1999).

There is no universally accepted definition of EC

(Ngai and Wat, 2002). Using (Turban et al., 2004)

definition of e-commerce, “E-commerce is described

as the process of buying, selling, or exchanging

products, services, and information via computer

networks, including the Internet.”. There are several

different types of EC, such as “Business-to-business

(B2B), which refers to e-commerce between

businesses or other organizations, and Business-to-

consumer (B2C), which refers to the e-commerce

model in which businesses sell to individual

shoppers.” (Turban et al., 2004). This paper focuses

on B2C e-commerce.

2 THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

AND HYPOTHESES

The issue of trust has been addressed from different

perspectives, including technological, social, and

institutional approaches; behavioural, and

psychological approaches; managerial, and

organizational approaches, marketing and e-

commerce (AlDiri and Hobbs, 2006). Customer trust

is a significant issue in EC since online services and

products are typically not immediately verifiable

(Gefen and Straub, 2004). Customer trust

significantly affects new customer acquisition,

customer retention and purchase intentions (Ba and

Pavlou, 2002). Customer trust also significantly

affects information-technology (IT) adoption by

online customers (McKnight and Chervany, 2001),

since customers need to trust an IT before they adopt

it. In contrast, lack of trust is often cited as a

significant barrier to e-commerce adoption; it is one

of the most frequently cited reasons for customers

227

Al-Diri K., Hobbs D. and Qahwaji R. (2007).

ARE MEDIA CUES REALLY A KEY DRIVER TOWARDS TRUST IN BUSINESS TO CONSUMER E-COMMERCE.

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on e-Business, pages 227-234

DOI: 10.5220/0002108602270234

Copyright

c

SciTePress

not purchasing from Internet (Egger, 2002). From

this perspective, how the buyer is afforded an

opportunity with trust is an important research issue

and a big challenge for online firms (Koufaris and

Hampton-Sosa, 2004). Also it has become

increasingly important to understand the factors

which influence consumer purchase decisions in the

web context (Siala et al., 2004). Trust is a complex

and a hard to describe concept that has been widely

studied (Ambrose and Johnson, 1998); it remains

numerous and confusing (Stewart, 1999). However,

the most commonly cited definition of trust in

various contexts [according to (Rousseau et al.,

1998)] is the “willingness of a party to be vulnerable

to the actions of another party based on the

expectations that the other will perform a particular

action important to the trustor”, as proposed by

(Mayer et al., 1995). This conceptualization of trust,

which is also known as “trusting intentions”

(McKnigh et al., 2002) and trustworthiness

(Jarvenpaa et al., 2000), is based on a set of beliefs

that others upon whom one depends will behave in a

socially acceptable manner by showing appropriate

integrity, benevolence, and ability (Doney and

Cannon, 1997); (Gefen, 2002); (Mayer et al., 1995);

(McKnigh et al., 2002). These three beliefs are

labelled by most research as “trust beliefs” (Gefen,

2002); (McKnigh et al., 2002), although (Mayer et

al., 1995) labelled these as “trustworthiness”. Ability

deal with the e-Vendor's knowledge, competence,

and provision of good service. Integrity deals with

the e-Vendor's honesty and keeping of promises.

The benevolence deals with the e-Vendor's

benevolence, willingness to assist and support, and

with consideration toward the customer. Trust is

defined by some research as behavioral intentions,

by others as beliefs, and yet by others as a mixture

of both.

The existence of multiple definitions of trust in

the research is probable due to two reasons

(McKnigh et al., 2002): First, each discipline views

trust from its own exclusive perspective. Second,

trust by itself is a fuzzy term. The other difficulty

has been that empirical research has driven most

definitions of trust, and one needs only to define one

type of trust to do empirical research. Within the

compact e-commerce domain of research, trust has

been defined as a willingness to believe (Clarke,

1999), or an individual’s beliefs, regarding the

various attributes of the other party (Yamagishi and

Yamagishi, 1994).

In the online context, the definition and

operationalization of trust has been a source of

considerable debate (AlDiri and Hobbs, 2006). Very

often, trust has been defined as a belief regarding the

characteristics of the company to be trusted (Kumar

et al., 1995; Luhmann, 1979; Mayer et al., 1995;

Fung and Lee, 1999; Menon et al., 1999; Stewart,

1999). Those characteristics usually include the

company’s integrity, benevolence and competence

or ability, all of which comprise the company’s

trustworthiness, as perceived by the customer.

In this study a further isolated type of perceived

company trustworthiness was examined by using

only new customers in the study sample. Therefore,

the results indicate how customers develop initial

trust beliefs in a company online after only their first

visit and without having any prior experience with

the company (McKnight et al., 1998; McKnight et

al., 2002). Past experience with a company was

recognized as an important determinant of customer

trust but this study does not examine it. Instead we

look at how information gathered during an initial

interaction with the web site can affect the

customer’s initial perceptions of the e-commerce

vendor’s trustworthiness.

2.1 Online Trust and Interpersonal

Cues

In contrast to face-to-face commerce and to other

applications, there are typically no social

interactions in e-commerce websites, neither direct

nor implied (Gefen and Straub, 2004). Online

vendors face a significant challenge in making their

virtual storefront socially rich (Kumar and Benbasat,

2002). Online consumers’ perceptions of social

presence cues which are also known as interpersonal

cues have been shown to positively influence trust

and their subsequent intention to purchase from a

commercial website (Chong et al., 2003), (Kumar

and Benbasat, 2002). In the field of human-computer

interaction (HCI), (Nass et al., 1996) created a

paradigm of “Computers Are Social Actors”

(CASA); this approach by some researchers has

been referred to as ‘‘virtual re-embedding’’

(Riegelsberger and Sasse, 2002). The CASA

paradigm suggests that social dynamics and rules

guiding human-human interaction apply equally well

to human-computer interactions. Many studies have

testified the CASA paradigm (Lee et al., 2003).

Under this paradigm, researchers constantly found

out that individuals tend to think of media (i.e.

computers, computer interfaces, agencies, computer

generated voice, etc.) as their counterparts -

intelligent social beings - when they are interacting

with them. Instilling a sense of human presence and

sociability can be accomplished by providing the

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

228

means for actual interaction with other humans or by

stimulating the imagination of interacting with other

humans.

In a Web context, actual interaction with other

humans may be incorporated through Website

features such as e-mail after-sales support, virtual

communities, chats, message boards, socially-rich

picture content, socially-rich text content, human

audio, human video, avatar ,and human Web

assistants (Lee and Turban, 2001), (Kumar and

Benbasat, 2002), (Zheng et al., 2002). The pictures

effect may be even more distinct, but not consistent

in research studies. However, research on the use of

personal photos in website is a little bit

contradictory, with some studies finding such

images to be a positive cue ((Nielsen, 1996); (Fogg,

2002);(Steinbruck et al., 2002), while others finding

them to be neutral cues (Riegelsberger and Sasse,

2002). It should be emphasized, then, that the studies

on applying social cues, especially photographs, to

website design are still at a preliminary stage.

However, many researchers are presently applying

potentially effective methods to enhance online trust

by adding a substitute human presence and actual

contact opportunities to the otherwise impersonal e-

commerce interface (Wang and Emurian, 2005). As

a result of the foregoing it is hypothesised that:

H-1: Subjects differ significantly on their rating

of initial trust and trust intention across vendor’s

websites.

H-2: The higher rating of vendor’s websites

trustworthiness will be for those presenting video

clips then for that with photos than for those without

photos respectively.

2.2 Website Design and Culture

The global nature of the Internet raises questions

about the trust effects across cultures as well. The

creation of virtual organizations brings specific

consequences for communication (El-Shinnawy and

Markus, 1998). Specifically, non-face to face

communication becomes more important as

technology shrinks the world, bringing multiple

cultures into virtual relationships, and increasing

global communication and business opportunities.

There are several reasons to assume that culture

may be an important factor in on-line trust (Clarke,

1999). Online trust research has been limited to a

western context (Pavlou and Fygenson, 2006).

Although trust has been examined for many years,

most of the research on consumer trust focuses on

consumers in English-speaking countries and newly

industrialised countries (Lee and Turban, 2001).

However, the trust theories and mechanisms

developed in the western context might not apply for

other societies, especially since cultures may affect

the antecedents of trust (Chong et al., 2003). Also,

the global nature of e-commerce has recently led

researchers to question whether the trust effects that

they have identified generalise across different

cultures (Siala et al., 2004).

There are many studies comparing the formation

of consumer trust between two different countries,

e.g., (Lee and Turban, 2001). They provided

empirical evidence that trust directly influences

consumer attitude across cultures; i.e., trust is

important for all cultures studied. Thus, there is a

need to re-examine the notion of trust and identify

its determinants in the context of different markets

and cultures (Lee and Turban, 2001) since it

represents a central imperative (Jones, 2002). The

implications of these kinds of research are

significant as an exploratory step for how various

elements of web design must be considered in the

context of culture, and for accessibility of

increasingly larger non-English-speaking

populations to the Internet (Cyr and Trevor-Smith,

2004). The lack of cultural and linguistic integrity in

direct B2C models could be one of the reasons why

B2C e-commerce is lagging behind B2B (business to

business) e-commerce (Siala et al., 2004). Symbols

are an important element denoting culture (Marcus

and Gould, 2000). Symbols are “metaphors”

denoting the actions of the user (Barber and Badre,

2001), and it can be varying and may represent a

wide range of features (Fernandes, 1995). One

important form of symbols is multimedia relating to

culture which few researchers have examined. On

the basis of the discussion above, the following

additional research hypotheses were proposed:

H-3: Across websites including human portraits

there will be significant statistical differences in

their trustworthiness between websites with local

interpersonal cues and websites with foreign

interpersonal cues.

H-4: Saudi subjects will trust a website with

Saudi interpersonal cues (photo) more than a web-

site with Western interpersonal cues (photo).

2.3 System Assurance

Much literature, specifically related to the trust

model and its derivatives, suggests that trust also

depends on system assurance which is also known as

Institution-Based Trust (McKnigh et al., 2002).

Accordingly, system assurance and trusting

disposition can be added as control variables. (Teo

ARE MEDIA CUES REALLY A KEY DRIVER TOWARDS TRUST IN BUSINESS TO CONSUMER E-COMMERCE

229

and Liu, 2005) have defined system assurance as

“the dependability and security of a vendor's online

transaction system, which enables transactions

through the Internet to be secure and successful”;

This construct comes from the sociology that people

can depend on others because of structures,

situations, or roles that provide assurances that

things will go fine. Hence, it was hypothesized that:

H-5: The more positive/negative the Institution-

Based Trust, the higher/lower the level of initial trust

in the e-vendor.

2.4 Dispositional Trust

Dispositional trust or propensity to trust is a

“generalized expectation about the trustworthiness

of others” (McKnight, et al., 2002). It is a measure

of an individual's propensity to trust or distrust

others, or it is the general willingness to trust other

people. This construct comes primarily from

psychology. It is influenced by previous

experiences, personality attributes, and cultural

background (McKnigh et al., 2002). Much research

has revealed that an individual's propensity to trust

has a major influence on initial trust (McKnigh et

al., 2002, Gefen and Straub, 2004). Since individuals

differ considerably in their general propensity to

trust other people based on the mentioned factors, it

is reasonable to hypothesise that:

H-6: The higher the consumer’s propensity-to-

trust, the higher the level of initial trust in the e-

channel.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study was designed as a one-factor experiment

manipulating three levels of Website interpersonal

cues. Each of the four specially-designed websites

displayed the same products but each represented

different vendors. Only the interpersonal cues

elements were manipulated on the sites. Thus, this

study attempted to investigate and examine the

effects of the interpersonal cues or the social cues

that can be manipulated by facial photo, video clip,

and culture as control variables, which used Saudi

and Western people in each of the interpersonal cues

when forming the initial trust toward online vendors.

In addition the study set out to measure some

auxiliary variables that have been discussed in the

literature i.e. propensity or disposition to trust and

system assurance or Institution-based trust.

3.1 Experimental Websites

The researchers first made an observational survey

for Saudi society to discover what are the most

popular and interesting online products for the

Saudi. The researcher found that the laptop is the

product that satisfies these conditions. Beside these

factors this product carries a considerably higher

financial risk than buying other simple online

products; so this can be used in this kind of

experiment.

The researchers then used the four most famous

reviewer business sites; BizRate.com,

ResellerRating.com, PriceGrabber.com, and

Epinion.com to facilitate the task of rating four

online shopping sites based on specific criteria. In

this selection western shopping sites were selected

as they constituted a realistic scenario with relatively

high risk, due to the vendor and the users being in

two different countries. The selection was based on

the high trustworthiness of the vendors, and the

number of reviewers of the selected site.

Semi-functional copies of the websites were

designed including the homepage and some

subsequent layers depending on the available links

in each layer, so that participants were able to

browse and search general information on the site,

such as ‘about us’, privacy and security policies

including access to detailed product descriptions.

Also any certification or reputation seals that were

present on some pages were removed. The media

cues (photo, video clip) were put in an appropriate

and attractive place in the first page of the site

showing the selected product (without deleting or

hiding anything from the page itself). This page was

connected to the entire website; so the subject could

browse and search the site.

The perceived trustworthiness of the photos that

were used in the experiments needed to be

established in a pre experiment. This also served to

establish how professional and ‘real’ the photos

were in representing a customer service. More than

sixty candidate photos were collected of men

(western, and Saudi), which were reviewed and the

most suitable were chosen to represent the

appropriate professional customer representatives of

an online shopping site. Five professionals in

computing and business were then invited to rate the

photos and select the most appropriate. These photos

were then subsequently used in these experiments.

For the video clips, the same procedure was

followed. See figure-1

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

230

3.2 Data Collection

Data for this research experiment was collected

through questionnaires, targeted at general Internet

users, in the context of experiments. All

experimental tasks during this research experiment

were performed in a computer laboratory. The

research instrument to measure the constructs of

interest was developed by adapting existing

measures from the literature to the current research

context (Teo and Liu, 2005) and (Gefen et al., 2000),

(McKnigh et al., 2002), (Kammerer, 2000). All

items were scored on a five-point Likert-type scale

ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly

agree.

As the experiments were conducted in Saudi

Arabia (Saudi being predominantly Arabic-

speaking) the questionnaire, originally written in

English, was translated into Arabic by a bilingual

person whose native language is Arabic. The Arabic

questionnaire was then translated back into English

by another bilingual person.

These two English versions were then compared

and no item was found to deviate significantly in

terms of language. This process was conducted not

only because it can prevent any distortions in

meaning across cultures, but also because it can

enhance the translation quality.

The questionnaire consisted of five sections that

extracted some demographic characteristics, online

purchasing experience, propensity or disposition to

trust, and system assurance or Institution-based trust

and items reflecting the most common initial trust

belief dimensions, which are ability, integrity,

benevolence (Gefen and Straub, 2004), and the trust

intentions, that is, intention to engage in trust-related

behaviors with the Web vendor. Subjects for the

study were general Internet users representing

undergraduate and graduate students at a famous

computer training institute. The use of student

subjects was deemed appropriate since online

consumers are generally younger and more highly

educated than conventional customers, which makes

student samples closer to the online consumer

population (Saarenp and Tiainen, 2005). Thus

students are quite representative of online shoppers.

Figure 1: Snap shot of experimental websites.

3.3 Experimental Procedure

At the beginning of the experiment all participants

were asked to open the experiment window on their

computers and read the introduction that explains the

objectives of the experiment and the total estimated

time that it would take (namely 45 minutes). This

study induced financial risk in a laboratory situation.

While it does not fully represent a real-world risk,

however, it allows combining a laboratory setting

with some elements of real-world risk by informing

ARE MEDIA CUES REALLY A KEY DRIVER TOWARDS TRUST IN BUSINESS TO CONSUMER E-COMMERCE

231

participants that the experiment website

trustworthiness has been assessed and rated by

independent business reviewer sites where one of

their tasks is to identify the trustworthiness of each

shopping site, and whose rating matches the real rate

of the trustworthiness which will be entered in a

lucky draw with prizes up to a laptop and a mobile

phone set which will be offered in a random draw

conducted at the end of the study. Then participants

were asked to fill out sets of questionnaires that

elicited some demographic characteristics, online

purchasing experience, disposition to trust, and

system assurance. Each subject was then asked to

look at the four websites and perform a general

browsing in the websites. This involved looking at

the website and then evaluating this e-commerce

vendor using the online vendors’ trust questionnaire.

This process was repeated for all of the four

websites. To control the effects, the order of

presentation of the four experimental websites was

completely counterbalanced. When subjects finished

seeing all the four websites and filling in their

questionnaires, they were asked to do another task.

In this task participants were asked to assess the

websites that they had seen, and to rank them

according to their preferences.

4 DATA ANALYSIS AND

DISCUSSION

All the data analysis was conducted using SPSS

windows software package version 12. A total of 72

subjects participated in this study, all of them males,

with ages between 18-25 and 26-35 respectively,

most of them (79.2%) preparing for bachelor

degrees in computer studies at a major Saudi

computer institute. As expected, this group was

‘Internet-savvy’ with over 39% of the respondents

spending between 6-10 hours online per week. On

average, the majority made at least 1 online purchase

per week and (28%) of the respondents spent

2000SR and more per online purchase. As

mentioned above, the vendor trustworthiness

questionnaire was built to cover all the common

dimensions or factors of trust belief that the

researchers in this field mostly agree with, namely

integrity, ability, and benevolence. Also it tested the

subjects’ trust intention regarding online vendors

that they saw. Bivariate correlation (Kendall’s tau-b)

results showed the correlation between the most

common constructions of trust belief for each

website significant at the 0.01 level.

4.1 Testing the Research Hypotheses

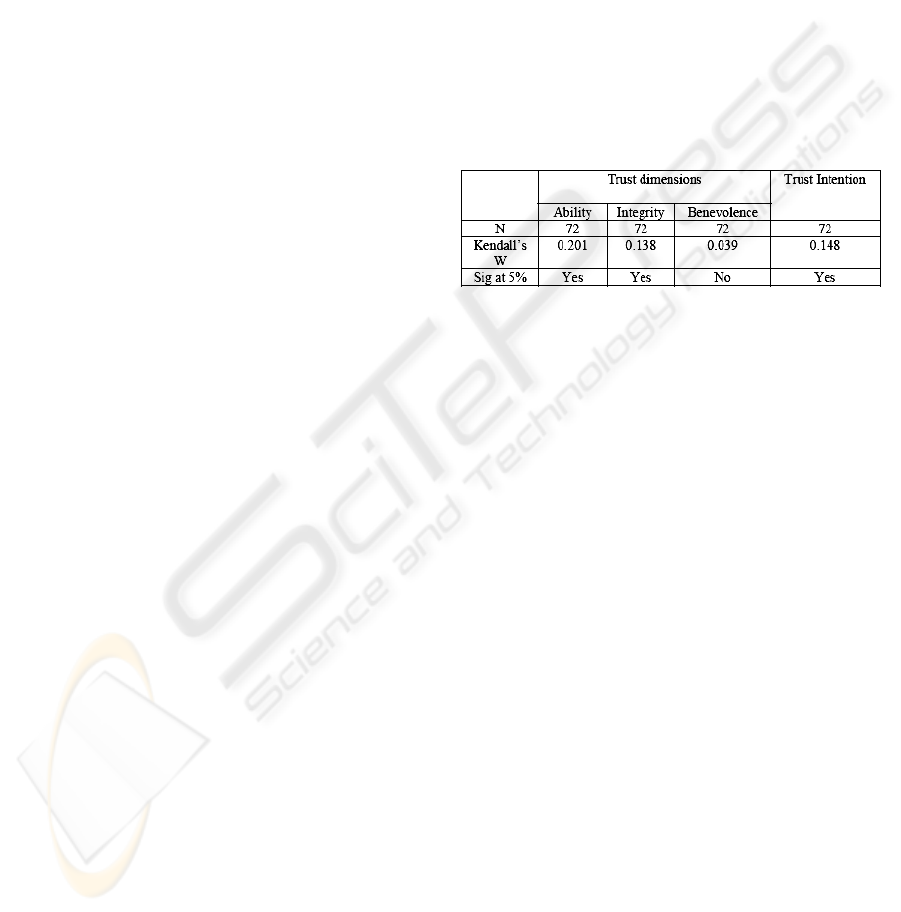

To test the first hypothesis (H-1), a nonparametric

K-Related samples, Kendall’s W test was computed

between each of the trust belief factors and trust

intention for all the websites to see if there is any

significant statistical difference between subjects’

answers regarding the trustworthiness of the four

websites. Results showed that the subjects differed

significantly on their rating of their initial trust and

trust intention regarding the four vendors’ websites

and in the light of the overall statistical significance

(p< .05) the first hypothesis was supported. See

table-1.

Table 1: Kendall’s W test for Trust Belief and Trust

Intention for the four websites.

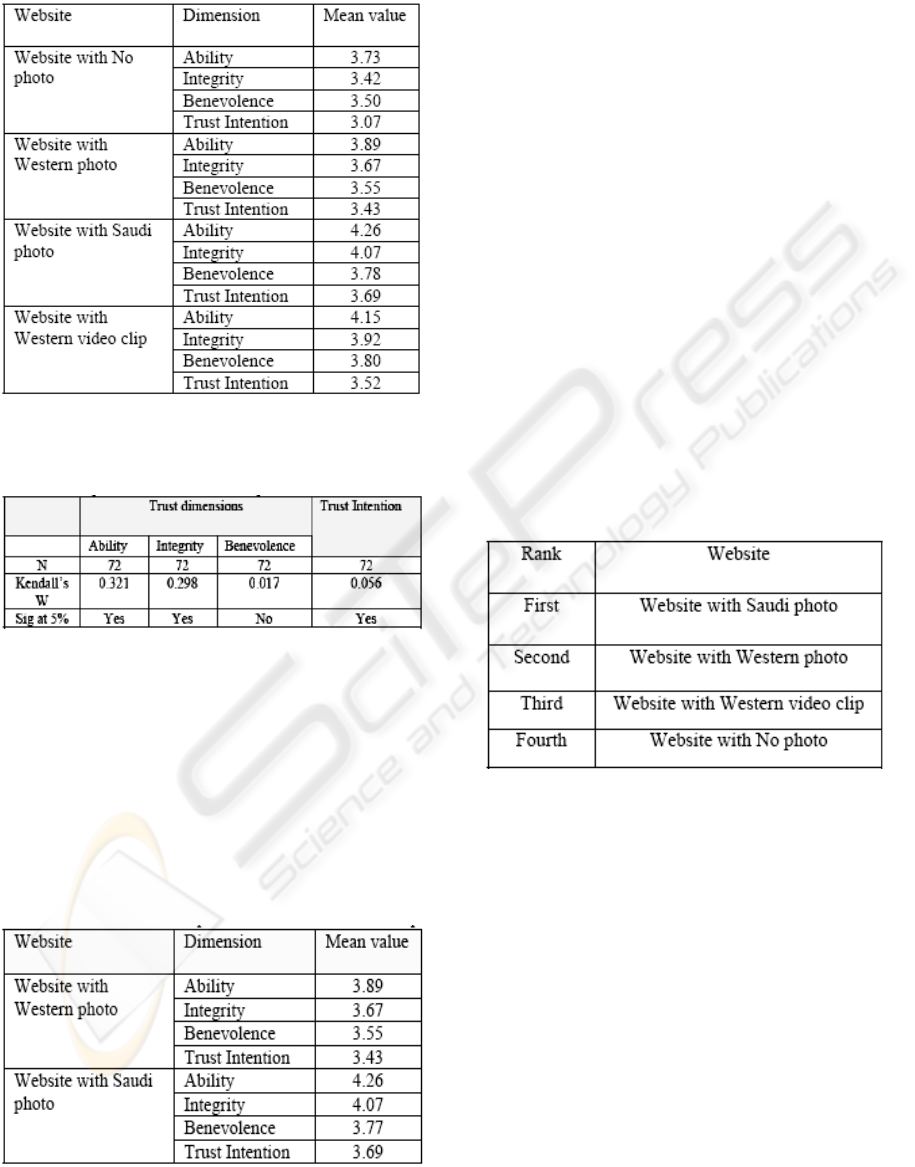

For the second hypothesis (H-2) in order to test

this hypothesis, we have compared the average mean

value for the three dimensions of trust belief and

trust intention between the four websites, See Table-

2. Subjects rated the initial trust and trust intention

for photo website as the highest, the video clip

website next, and the no photo website as the lowest.

Thus, the second hypothesis was partially supported,

since the vendor with video clip came in the second

rank rather than the expected first position. A

possible explanation for this unexpected result is that

the video clip was not recorded to professional

standards. For the third hypothesis (H-3) the same

procedure adopted for testing the first and the

second hypothesis was used to test the third and the

fourth hypothesis, but in this case between two

vendors websites only (website with Saudi photo

and website with Western photo). Kendall’s W test

showed the subjects differ significantly on their

rating of their initial trust (ability and integrity of

trust belief, but not for benevolence dimension) and

trust intention regarding the two vendors websites as

a result of the overall statistical significance (p<.05),

the third hypothesis was fully supported see table-3.

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

232

Table 2: Mean Value for Trust Belief and Trust Intention

for Each Website.

Table 3: Kendall’s W test for Trust Belief and Trust

Intention for website with Western photo and website with

Saudi photo.

With respect to the fourth hypothesis (H-4), we

compared the average mean value for the three

dimensions of trust belief and trust intention

between the two websites, See Table-4. The result

indicated that the subjects rated the initial trust and

trust intention for website with Saudi photo higher

than the website with Western photo. So the fourth

hypothesis is supported.

Table 4: Mean Value for Trust Belief and Trust Intention

for website with Western photo and website with Saudi

photo.

The fifth hypothesis about the system assurance

(trusting Internet environment) (H-5) was tested

using a non-parametric correlation test (Kendall’s

tau_b test) between system assurance questions and

the trust belief and trust intention questions in each

website; no significant correlations between them

were evident, so this hypothesis was not statistically

supported. The same test was done with the

dispositional trust (H-6) when no statistically

significant correlation was found.

4.2 Preference Ranking

Participants were asked to rank the four vendors

according to their preference. The question was

phrased as follows: “Assuming that all sites offer the

product you are looking for at the same price with

the same condition, consider which site you would

be most comfortable buying from.” In contrast to the

other measures, this measure forced the participants

to bring the vendors into a hierarchical order. The

order of preference of all websites is presented in

table-5.

Table 5: Order of Preference Rank for Each Website.

Finally many nonparametric correlation tests

were carried out to see if there are any significant

differences between the trust belief, trust intention

and participants’ age, education level, Internet

usage. The results showed no statistical significance

differences between all these variables.

5 CONCLUSION

The results indicate that embedding of the

interpersonal cues in a website is an effective

strategy to increase consumer trust in an online-

vendor. Displaying a portrait photograph helps to

create interpersonal cues and bring the impersonal

process of e-commerce closer to the familiar

situation of a face-to-face conversation, since

customers can develop a quasi-social relationship to

ARE MEDIA CUES REALLY A KEY DRIVER TOWARDS TRUST IN BUSINESS TO CONSUMER E-COMMERCE

233

the person shown in the picture. The displayed

person represents a real-world representative of an

otherwise intangible, virtual company. Thus, s/he

creates an entry point for the consumer to the on-line

vendor and facilitates the establishment of customer

trust. For the design of e-commerce websites it can

be concluded that embedding a photograph or a

video clip of a company’s representative may be a

simple, yet powerful way to increase the

trustworthiness of an online-vendor. This

experiment tested the effect of adding a facial photo

from two different cultures (Western, Saudi) to an e-

commerce vendor’s homepage on user trust. It thus

focused on the symbolic use of interpersonal cues.

This goal, despite its importance for the

development of trust in ecommerce, has not been

addressed in previous researches. This experiment

found that media cues in the interface are indeed

able to affect a vendor’s trustworthiness based on

the surface cues it contains. A clear picture emerged

regarding the effect of photos from different

cultures. Most of the previous studies tested the

effects of adding one photo to a mock-up of one e-

commerce site. This experiment was aimed at

overcoming this limitation by testing several photos

on several semi-functional copies of existing

vendors’ sites. In addition, this experiment

introduced a method for measuring trust that

required participants to make decisions under

conditions of financial risk. Finally during the

experiment design there was an expectation that the

website with the video clip would be ranked as the

highest since video can display more interpersonal

cues than photos, but this turned out not to be the

case, possibly due to its lower quality. Further

research will investigate how embedding can be

done most effectively and how different re-

embedding strategies interact.

6 IMPLICATION

Based on the findings of our experiment we suggest

that web designers and e-commerce vendors should

keep in mind the following recommendations when

introducing e-commerce applications in Middle East

countries in general and in Saudi Arabia particularly:

There is a significant effect of a media cue

(photo, video clip) in B2C e-commerce websites.

The positive attractive impressions of a media cue

can thus help e-commerce vendors in the process of

converting a visitor to a customer. The findings of

this experiment underline the importance of the

interface as a communicator of trustworthiness.

In B2C e-commerce applications it is very

important to carefully select and design the various

elements of web design in the context of culture. It is

expected that when web sites are appropriate and

culturally sensitive, then users will have increased

access to content and enhanced user experiences.

REFERENCES

Adam, N. R., Dogramaci,O ,Gangopadhyay, A and Yesha,

Y. (1999) Electronic Commerce: Technical, Business,

and Legal Issues, Prentice-Hall,Upper Saddle River.

Al-Diri , K., , Hobbs DJ and R, Q. (2006) In Proceedings

of the IADIS e-Commerce 2006 International

ConferenceBarcelona, Spain, pp. pp 323-327.

AlDiri, K. and Hobbs, D. (2006) In the seventh

informatics workshop, Bradford University, Bradford

University.

Ambrose, P. J. and Johnson, G. J. (1998) In the Fourth

Conference of the Association for Information

Systems, pp. 263-265.

Ba, S. and Pavlou, P. A. (2002) MIS Quarterly, 3, 243-

268.

Barber, W. and Badre, A. N. (2001) In 4th Conference on

Human Factors and the WebNew Jersey, USA.

Chong, B., Yang, Z. and Wong, M. (2003) Proceedings of

the ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, 5,

213-219.

Clarke, R. (1999) Communications of the ACM, 2, 60-68.

Cyr, D. and Trevor-Smith, H. (2004) Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and

Technology, 55, 1199-1206.

Doney, P. M. and Cannon, J. P. (1997) Journal of

Marketing, 2, 35-51.

Egger, F. N. (2002) CHI.

El-Shinnawy, M. and Markus, M. L. (1998) Professional

Communication, IEEE Transactions on, 41, 242-253.

Fernandes, T. (1995) In ACM Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ’95 Mosaic of

CreativityNew York.

Fogg, B. J. (2002).

Gefen, D. (2002) Database for Advances in Information

Systems, 33, 38.

Gefen, D. and Straub, D. W. (2004) Omega.Oxford, 32,

407.

Gefen, D., Straub, D. W. and Boudreau, M.-C. (2000)

Communications of the Association for Information

Systems, 4, 1-70.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., , Tractinsky, N. and Vitale, M. (2000)

Information Technology and Management, 1, 45.

Jones, A. I. J. (2002) Decision Support Systems, 33, 225-

232.

Kammerer, M. (2000) Zurich: Lizenziatsarbeit der

Philisophischen Fakultaet der Universitaet Zurich.

Koufaris, M. and Hampton-Sosa, W. (2004) Information

& Management, 41, 377.

Kumar, N. and Benbasat, I. (2002) e-Service Journal, 1.

Other references did not include due to space limitation.

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

234