MOBILE DECISION MAKING AND KNOWLEDGE

MANAGEMENT

Supporting Geoarchaeologists in the Field

Martin Blunn, Julie Cowie, David Cairns

Department of Computing Science and Mathematics, University of Stirling, Stirling, U.K.

Clare Wilson, Donald Davidson

School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, U.K.

Keywords: Mobile Decision Support, Archaeology.

Abstract: There is a professional responsibility placed upon archaeologists to record all possible information about a

given excavated site of which soil analysis is one important but frequently marginalised aspect. This paper

introduces SASSA (Soil Analysis Support System for Archaeologists), whose primary goal is to promote

the wider use of soil analysis techniques through a selection of ‘web based’ software tools. A description is

given of the field tool developed which supports both the recording of soil related archaeological data in a

comprehensive manner and provide a means of inferring information about the site under investigation.

Insight is gained through a user evaluating numerous decision trees relating to pertinent archaeological

questions. Whilst the field tool is capable of working in isolation, it offers a superior experience when

operated in unison with a Wiki. A brief discussion of the use of the Wiki application within the SASSA

project is presented.

1 INTRODUCTION

Applying geoarchaeology techniques to in-situ

monitoring of archaeological deposits can be an

arduous task for a non-specialist. They have to

identify questions relevant to the site and determine

suitable analytical techniques and sampling methods

to employ, all of which require complex decisions to

be made. Although there are many sources of

material citing good practice when analysing site

deposits, the nature of an archaeological dig does not

easily facilitate access to such information.

This paper introduces SASSA: a Soil Analysis

Support System for Archaeologists. SASSA is a

mobile knowledge-based tool that provides a means

by which pertinent information used to assist in

analysis is easily accessible yet provided in a

comprehensive manner. In addition, SASSA

incorporates decision support technologies to aid the

archaeologist in both their analysis of a site and

recording of important site data.

In Section 2 we begin by discussing the field of

geoarchaeology, highlighting some of the issues that

contribute to the complexity of the area. Section 3

reviews the current state of mobile decision support

research and outlines the relevance of SASSA to this

domain. Section 4 focuses on the SASSA field tool

with the underlying technology described in Section

4.1 and use of the tool discussed in Section 4.2.

Section 4.2 also illustrates how the tool might be

used by means of an example scenario. Conclusions

and future work are provided in Section 5.

2 GEOARCHAEOLOGY

Geoarchaeology is a broad discipline with much to

offer the archaeologist. Geoarchaeological research

has addressed a diverse number of issues; it has been

applied not only to archaeological sites and

landscapes, but also to experimental and

ethnographic research, and in-situ monitoring of

archaeological deposits.

57

Blunn M., Cowie J., Cairns D., Wilson C. and Davidson D. (2007).

MOBILE DECISION MAKING AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT - Supporting Geoarchaeologists in the Field.

In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - AIDSS, pages 57-62

DOI: 10.5220/0002354500570062

Copyright

c

SciTePress

The archaeological questions addressed by soil

analysis fall broadly into two categories; site-

specific and landscape level. At the site level there

are issues over formation processes involving the

anthropogenic, depositional and human history of

the site. Such studies address the nature, source and

processes leading to the accumulation of deposits

through, for example, the use of multi-element

analysis to address space use and the identify

functional areas (Entwistle et al., 2000; Knudson et

al., 2004; Wells, 2004)

and the effects of

bioturbation

(Balek, 2002; Grave and Kealhofer,

1999) phosphatisation

(McCobb et al, 2003), and

waterlogging

(Caple, 1998) on the integrity of the

stratigraphic record. At the landscape level questions

concern human-environment interactions, for

example, the impact of human activity on erosion in

the wider landscape

(Wilkinson, 2005), resource

management in archaeological landscapes (Simpson

et al, 1998) and the effect of large scale natural

disasters on settlement location (Goff et al, 2003).

The complexity of the area means it can be

difficult for a non-specialist to identify the questions

relevant to a particular site and match this to the

relevant analytical techniques and sampling methods

or to critically evaluate the results. There is a good

geoarchaeological knowledge base already

available; it is the presentation of this material in a

manner that is easily accessible and comprehensible

to an interested non-specialist that is lacking. An

example of this is the use of multi-element

techniques to address questions of space use across

sites, or to identify sites within the landscape. The

question being asked influences the sampling

regime, and case studies of these two approaches

might include the identification of site extent at

Shapwick (Aston et al., 1998), or the identification

of activity areas in a classical site in Honduras

(Wells, 2004). English Heritage guidelines

(Avala et

al., 2004) provide questions associated with different

types of deposit linked to methods of investigation

and field diagnostic tools, such as finger texturing

flow charts, but access to specialist literature and the

time needed to absorb the specialised information

are still a problem for many archaeologists.

The development of the Soil Analysis Support

System for Archaeologists (SASSA) is aimed at

addressing the issues outlined above.

3 MOBILE KNOWLEDGE AND

DECISION SUPPORT

Knowledge management systems embrace

heterogeneous approaches for representing and

processing human knowledge to enhance decision-

making capability of human decision-makers (San

Pedro et al, 2003). With the event of mobile and

networked environments, there is a need to further

the approaches used. Mobile decision support and

knowledge systems have to handle the difficulties

and complexities brought about by context changes

in a mobile computing environment.

Mobile computing is a new technological

paradigm in which users access services via a range

of devices through a shared infrastructure, regardless

of their physical location or movement behaviour

(Zaslavsky

et al, 1998). Complexities and

uncertainties which derive from ensuring portability

of applications for a wide range of mobile devices

include frequent change in mode of operation, high

variability in performance and reliability, issues

surrounding visual display capabilities, finite

sources of energy, and facilitating recognition by the

system of the user, device and environment in which

the mobile computing takes place.

Related work in the area of mobile computer

support focuses on development of knowledge-based

services on hand-held computers (San Pedro et al,

2004; Cowie and Burstein, 2007). For example,

work on mobile clinical support systems, addresses

decision support such as knowledge delivery on

demand, medication consultant, therapy reminder

(Spreckelsen et al,

2000), preliminary clinical

assessment for classifying treatment categories(San

Pedro et al, 2003; Michalowski

et al 2003), and

providing alerts of potential drugs interactions and

active linking to relevant medical conditions (Chan,

2000). Most of these mobile support systems use

intelligent technologies and soft computing

methodologies (e.g., case-based reasoning, multi-

attribute utility theory) as background frameworks

for intelligent decision support.

This research builds on our existing work in the

area of mobile knowledge management, to provide a

central repository of archaeological information,

which is not restricted to location or platform. The

research addresses the changing way in which

information is required and decisions are made, the

impact this has on the type of systems developed,

and the emergent technologies that facilitate such

support. Our existing work in the area of developing

cross-platform systems designed for mobile /

(office) (Hodgkin et al, 2004; Cowie et al, 2006)

has

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

58

highlighted the suitability of such approaches to a

wide array of application areas. The SASSA field

tool extends this work both in the application area it

addresses and the technologies it uses.

4 THE FIELD TOOL

4.1 Technological Design

The field tool is tailored primarily towards two

categories of hardware device, static and mobile,

which in turn facilitate the use of the tool within

certain environments. The mobile category includes

devices such as a PDA (Personal Digital Assistant)

or ‘Smart phone’ whilst the static category

comprises of the more traditional desktop or laptop

computer. However, the two distinct functional

aspects of the field tool, recording the archaeological

data and evaluation of the data through the use of

decision trees, are both performed through the same

user interface and processing engine. The ubiquitous

HTML (Hyper Text Mark-up Language) browser

was identified as the most flexible interface for this

application, permitting user access via the hardware

devices listed above. The web interface technology

used is Sun Microsystem’s Java servlet technology

which is now common place within e-commerce

applications. Servlet technology was chosen due to

the availability of suitable API’s (Application

Program Interface), ease of design / implementation

of user session handling and its scalability under

load conditions. The Java servlet based system, used

in conjunction with the Apache Tomcat servlet

engine which assumes all conventional server

responsibilities, ensures that the tool utilises ‘open

source’ code and is thus freely available to all users.

Use of XML for data encoding

Through discussions with the domain specialists it

was determined that data storage requirements for

the project were not excessive and therefore both

user specified data and ‘knowledge data’ could be

stored within a proprietary XML (eXtensible Mark-

up Language) format data file. ‘Knowledge data’ is

defined within this tool as both descriptive content

and information associated with implementing the

tool. The XML format file is processed internally

using DOM (Document Object Model) methodology

to permit ease of manipulation and processing of

data. SASSA then produces output XML which is

rendered into XHTML through the use of XSLT

(eXtensible Style-sheet Language Translations)

technology. The output XML provides the structure

for the output content which is formatted for the

particular graphical user interface (GUI) of a given

user. The XSLT translation provides the flexibility

to tailor the style of presentation to the browser

being used. For example, the same output XML will

be used to generate different XHTML content

depending upon whether the user is accessing the

SASSA system via a PDA or desktop PC. It can also

be used to alter content to suit particular browsers or

even generate PDF equivalents of XHTML forms.

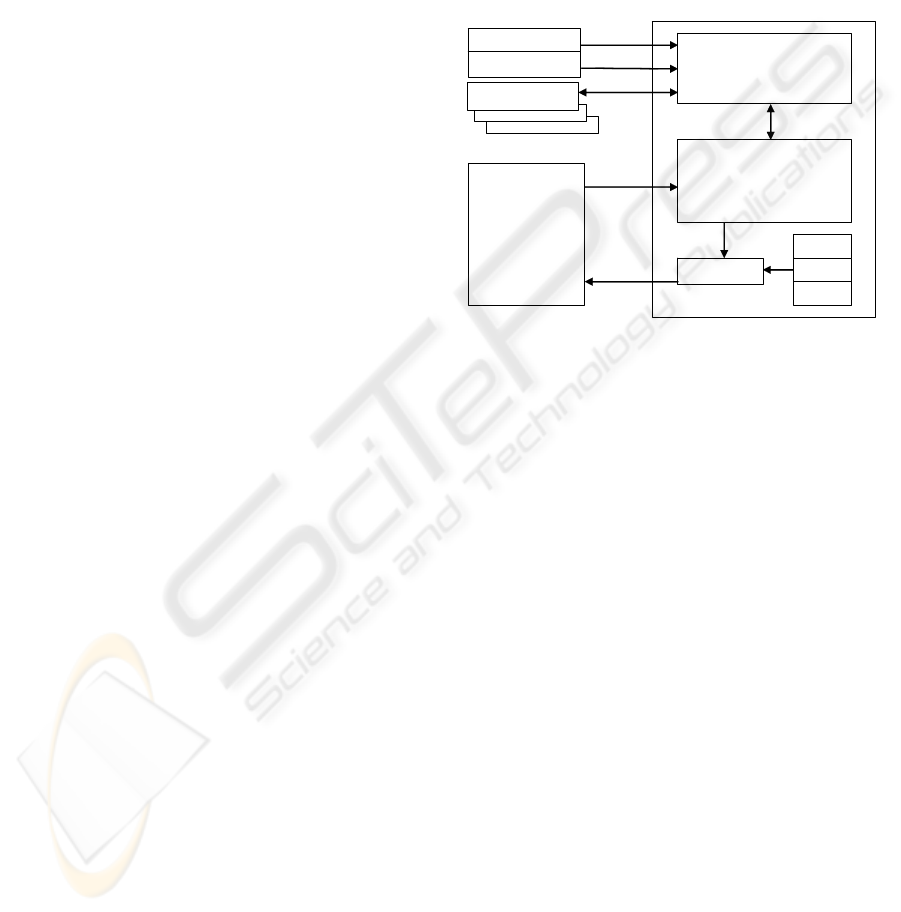

Figure 1: SASSA System Architecture.

A system diagram of SASSA is shown in

Figure 1 illustrating the principle software

components and their inter-relationships. The

normal process is for a user to log in to the SASSA

system at which point their XML data is loaded

into SASSA. A section of this XML data is then

requested, for example a ‘Site Details Form’. The

XML data encoding the site details is processed

into an intermediary XML output format

conveying more display related information. This

is then processed via an XSLT to produce

XHTML, and returned to the requesting

browser/device.

The SASSA field tool uses decision trees to aid

the geoarchaeologist in inferring information about

the site they are investigating. Insight is gained

through a user choosing from a compilation of

pertinent archaeological questions, each selected for

revealing the most information about the focus site

and ease / accuracy of answering. A decision tree is

formulated for each question comprising of a series

of sub-questions. It was felt the use of decision trees

(rather than other decision support techniques such

as case-based reasoning) was appropriate given that

feedback as to how an answer is attained is easy to

provide using this technique. In addition, the

infrastructure of decision trees seemed to be the

closest match to the current way in which decisions

XML

XHTML

Response

Request

HTTP

XML

User Data XML

XML

Parser / Builder

SASSA

Field Tool

Servlet

XSLT Parser

Configuration XML

PC XSL

PDA XSL

PDF XSL

Template XML

HTML

Browser

[PC/PDA/SmartPhone]

MOBILE DECISION MAKING AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT: Supporting Geoarchaeologists In The Field

59

about soil structures are made, thus facilitating an

easier transition from paper-based methods to the

SASSA tool than had a different approach been

adopted. A decision tree is constructed within a

proprietary XML data structure and evaluation

follows a standard ‘weighted sum’ methodology to

produce a specific ‘score’ for the question for a set

of specified answers to the sub-questions. The score

is presented to the user in a tabulated format that

contains not only the specific information on how to

interpret their score but that of other possible scores

in the answer range. This presentation format allows

the user to determine whether their results are

‘border line’ between score categories and thus draw

their own conclusions on the presented data. The

proprietary XML structure contains not only

presentation data (e.g. question text) and processing

data (e.g. weighting value for an answer) but allows

the implicit hierarchy of decision trees to be

captured through a combination of recursive data

structures and internal processing path links. A

similar hierarchical design structure is used for

storage of the site information archive and therefore

a common ‘XML processor’ has been used to

interpret both data structures.

4.2 Use of the SASSA Field Tool

When recording the archaeological record of a new

excavation two key aspects from a soil science

perspective have been identified; consistently

recording relevant data across multiple samples and

providing answers to a range of pertinent questions

which reveal more general information about a

particular site. Both of these functions have been

incorporated into the SASSA field tool. It is

envisaged that SASSA will be used both ‘on site’ for

immediate help with excavation decisions or in an

office environment when analysing retrieved data.

To facilitate this, SASSA is operable on a variety of

hardware platforms, each tailored to permit ease of

use within different situations. For example,

operating the field tool on a PDA (personal digital

assistant) or ‘Smart Phone’ will allow recording of

data within the excavation trench of interest.

Operation on a laptop/desktop PC within a site

office can facilitate group discussion on recorded

results at the end of a day’s recording activities.

4.2.1 Example Use of SASSA

Recording site information

Prior to a team of archaeologists arriving at an

excavation site, a significant amount of preparation

work and information gathering has been performed.

Some of this data is pertinent to the soil record of the

site and is important to document. Site information

is recorded in a hierarchical manner, where data can

relate to the site itself, specific sections or trenches

within a site, and contexts or layers within each

section. In accordance with this hierarchy, the

SASSA tool provides the facility to enter data about

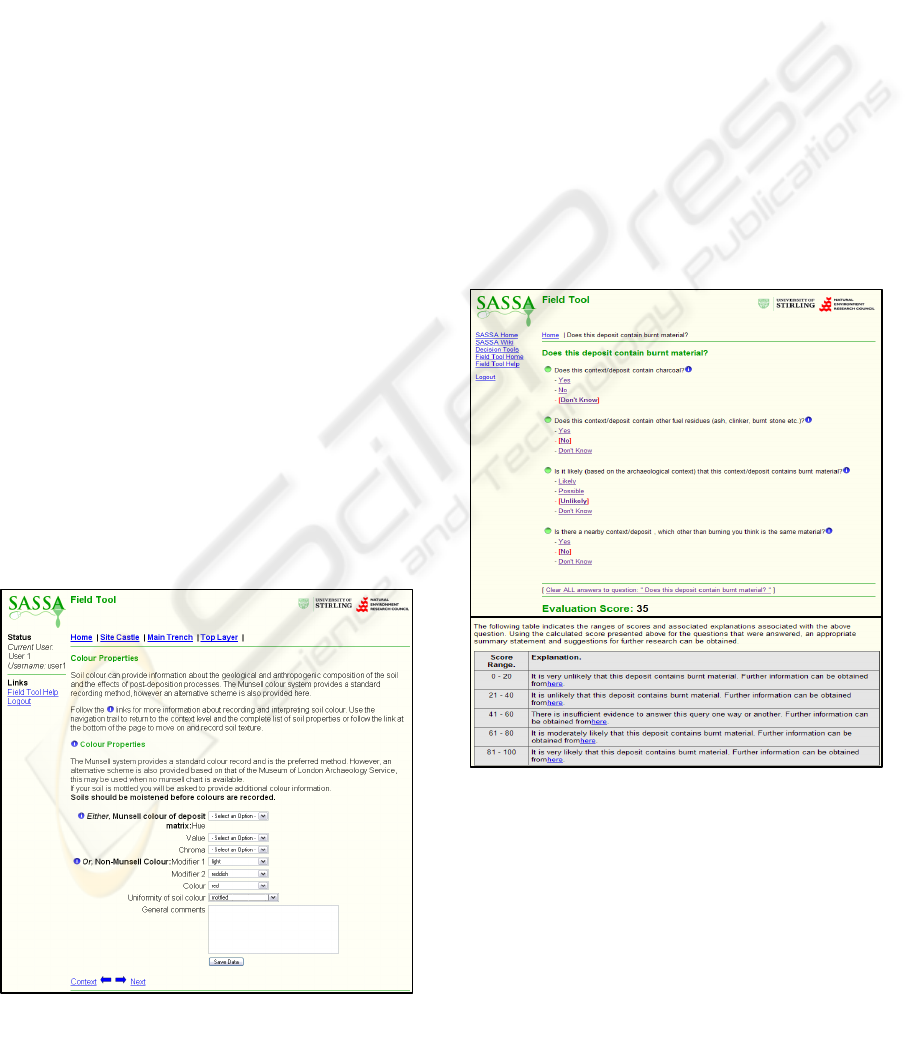

all aspects of a site as appropriate. In the screenshot

shown in Figure 2, we can see the user is providing

colour information for the Site Castle / Main Trench

Figure 2 : SASSA Site Details.

Figure 3: Field Tool Interface.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

60

/ Top Layer. The user is supported in this data

collection activity with a clear, ‘form style’ format

of data entry and links to textual definitions of

unusual terms and other information sources (such

as diagrams, photographs and case studies).

Use of decision trees for soil context discovery

The SASSA field tool uses decision trees as a means

of identifying the likelihood of certain soil properties

being present at a given site. Currently, the tool

focuses on what we regard as four of the most

prominent properties investigated at a site: the

presence of burnt material, whether the burnt

material (if present) occurred in-situ, the presence of

buried soil, and whether the deposit is natural. By

walking the user round the decision tree associated

with each of these properties, the tool collates

knowledge of the site and provides inferences

concerning the soil context. Figure 3 shows an

example of the questions the user is asked in relation

to the issue of burnt material. The questions asked,

and how the information provided by the user, is

utilised in providing new information to the user

dictated by the decision tree associated with the

issue being explored. In the example shown, the

answers supplied by the user provide an evaluation

score of 35. As is depicted at the bottom of Figure 3,

score ranges are provided along with how such

scores should be interpreted.

In addition to providing inferences about the site,

suggestions for further routes of investigation are

given. Such investigations include suggestions for

further tests that could be conducted and links to

further material provided by the SASSA tool that

could provide relevant case study or background

information.

5 CURRENT AND FUTURE

WORK

SASSA Extensions

The current focus of our work involves development

of the main SASSA website as a Wiki, from which

the field tool can be accessed. The ‘Wiki’ class of

software tool, typified by the world’s largest on-line

encyclopaedia ‘Wikipedia’ (Aronsson, 2002) allows

browser displayed content to be uploaded and

modified by registered users rather than just the site

developer. This ensures that content can remain

accurate and applicable as well as evolve with the

subject over a period of time. ‘MediaWiki’, has been

adopted for the SASSA system since it is the

technology on which ‘Wikipedia’ is based and users

are therefore more likely to be familiar with it.

SASSA Evaluation

Acceptance of the SASSA tools by the intended user

community is critical to the success of this project.

At the current stage of development, most effort has

been assigned to developing prototype versions of

the field tool. Evaluation of these development

models thus far has taken place through informal

discussion with a small selection of interested

persons. It is the intent however, to evaluate the

prototype tools more thoroughly at a series of formal

sessions across the UK at regular intervals in the

remaining time of the project.

Application to other domains

The infrastructure of SASSA has been developed

such that it is independent of the application,

ensuring portability of the system. We hope to

investigate other areas where the tool might be

applied once all components of the software are

complete.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the funding received for

this research by the Natural Environment Research

Council (NE/D000971/1).

REFERENCES

Aronsson, L 2002. Operation of a large scale general

purpose Wiki website: experience from susning.nu’s

first nine months in service. In Proceedings of the 6th

International ICCC/IFIP Conference on Electronic

Publishing, Czech Republic, November 6-8, 2002.

Verlag für Wissenschaft und Forschung.

Aston, M.A 1998. Chemosphere, 37; 465-477.

Ayala, G., Canti, M., Heathcote, J., Sidell, J., and Usai, R.,

2004. Geoarchaeology: using earth sciences to

understand the archaeological record. English

Heritage.

Balek, C. L. 2002. Buried artifacts in stable upland sites

and the role of bioturbation: a review. Geoarchaeology

17: 41-51.

Caple, C. 1998. Parameters for monitoring anoxic

environments. In (Eds.) M. Corfield, P. Hinton, T.

Nixon & M. Pollard, Preserving archaeological

remains in-situ. MoLAS, London: 66-72

Chan, A. 2000. WWW+ smart card: Towards a Mobile

Health Care Management System, International

Journal of Medical Informatics, 57, 127-137.

MOBILE DECISION MAKING AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT: Supporting Geoarchaeologists In The Field

61

Cowie, J., Burstein, F. 2007. Quality of data model for

supporting mobile decision making. Journal of

Decision Support Systems, In Press

doi:10.1016/j.dss.2006.09.010.

Entwistle, J.A., Dodgshon, R.A. and Abrahams, P.W.

2000. The geoarchaeological significance and spatial

variability of physical and chemical soil properties

from a former habitation site, Isle of Skye. Journal of

Archaeological Science 27: 287-303.

Goff, J.R. and McFadgen, B.G. 2003. Large earthquakes

and the abandonment of prehistoric coastal settlements

in 15th Century New Zealand. Geoarchaeology 18:

609-623.

Grave, P. & Kealhofer, L. 1999. Assessing bioturbation in

archaeological sediments using soil morphology and

phytolith analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science

26: 1239-1248.

Hodgkin, J., San Pedro, J., Burstein, F. 2004. Quality of

Data Model For Supporting Mobile Decision Making.

In Proceedings of Decision Support Systems

Conference, July 1-3, Italy.

Knudson, K.J., Frink, L., Hoffman, B.W. and Price, T.D.

2004. Chemical characterization of Arctic soils:

activity area analysis in contemporary Yup’ik fish

camps using ICP AES. Journal of Archaeological

Science 31: 443-456.

McCobb L.M.E., Briggs, D.E.G., Carruthers, W.J. and

Evershed, R.P 2003. Phosphatisation of seeds and

roots in a Late Bronze Age deposit at Potterne,

Wiltshire, UK. Journal of Archaeological Science 30:

1269-1281.

Michalowski, W., Rubin, S., Slowinski, R.,Wilk, S. 2003.

Mobile Clinical Support System for Pediatric

Emergencies, Decision Support Systems, 36, 161-176.

San Pedro, J. and Burstein, F. 2003. An intelligent

decision support model for tropical cyclone prediction,

submitted to International Journal of Intelligent

Systems in Accounting, Finance and Management,

Special Issue on Decision Making and Decision

Support.

San Pedro, J., Burstein, F., Churilov, L., Wassertheil, J.,

Cao, P. 2003. Intelligent Multiattribute Decision

Support Model For Triage. In Proc. of International

Conference in Information Processing and

Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Base

Systems, July 4-9, 2004, Perugia, Italy.

San Pedro, J., Burstein, F., Zaslavsky, A., Hodgkin, J.

2004. Pay by Cash, Credit or EFTPOS?

Supporting the User with Mobile Accounts Manager.

In Proc. of the 3rd Mobile Business Conference,

MBusiness Conference, New York, USA, 12th - 13th

July, 2004.

Simpson, I.A., Bryant, R.G. and Tveraabak, U. 1998.

Journal of Archaeological Science 25: 1185-1198.

Spreckelsen, C. Lethen, C., Heeskens, I., Pfeil, K.,

Spitzer, K. 2000. The Roles Of An Intelligent Mobile

Decision Support System In The Clinical

Workflow,URL

www.citeseer.nj.nec.com/spreckelsen00roles.html,

Accessed 11 Nov 2003.

Wells, E.C. 2004. Investigating activity patterns in

Prehispanic plazas: weak acid-extraction ICP-AES

analysis of anthrosols at Classic period El Coyote,

Northwestern Honduras. Archaeometry 46: 67-84.

Wilkinson, T.J. 2005. Soil erosion and valley fills in the

Yemen highlands and southern Turkey: integrating

settlement, geoarchaeology and climate change.

Geoarchaeology 20: 169-192.

Zaslavsky, A. and Tari, Z. 1998. Mobile computing:

Overview and current status. Special issue of

Australian Computer Journal on Mobile Computing,

30, 2, 42-52.

ICEIS 2007 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

62