mi-Guide : A Wireless Context Driven Information

System for Museum Visitors

Nigel Linge

1

, David Parsons

1

, Duncan Bates

1

, Robin Holgate

2

, Pauline Webb

2

David Hay

3

and David Ward

4

1

CNTR, University of Salford, Salford,

Greater Manchester, M5 4WT, UK

2

Museum of Science & Industry (MOSI)

3

BT Group Archives

4

SETPOINT Greater Manchester

Abstract. The growth in wireless and mobile communications technologies of-

fers many new opportunities for museums who are constantly striving to im-

prove their overall visitor experience. There is considerable interest in the use

of context-aware services to track visitors as they move around a museum gal-

lery so that exhibit information can be delivered and personalised to the visitor.

In this paper we present a visitor information system called mi-Guide that is to

be deployed within a new communications gallery at the Museum of Science &

Industry in Manchester. This paper also reviews previous research into con-

text-driven information systems and other context-aware museum applications.

1 Introduction

Traditionally technology in museums has taken the form of audio guides, push button

audio content and video display panels. More recently this has moved on to interac-

tive exhibits, providing facilities for users to give feedback through to allowing ac-

cess to content using desktop computers. The challenge for museums today is to

ensure that they continue to engage and excite visitors who are increasingly exposed

and immersed in today’s digital media and computer technology. Consequently mu-

seums are constantly striving to improve the visitor experience, nowadays in particu-

lar through the use of mobile communications technologies.

A small number of British museums, including Tate Modern, the Royal Institution

and the Fitzwilliam Museum, have already experimented with the use of mobile tech-

nology, including its location determining properties, to deliver context driven multi-

media tours. After product trials in 2002 and 2003-04 to great acclaim, Tate Modern

has recently launched a full product. The Technical Museum of Vienna claims to

have introduced the world’s first RFID multimedia system through which visitors can

record and share museum content that interests them [1]. There is also a commercial

product called Guide ID which bills itself as an alternative to the audio tour [2]. This

mobile multimedia guide product, which uses PDAs and proprietary infra-red tags,

has so far been deployed in the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam and

Linge N., Parsons D., Bates D., Holgate R., Webb P., Hay D. and Ward D. (2007).

mi-Guide : A Wireless Context Driven Information System for Museum Visitors.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Joint Workshop on Wireless Ubiquitous Computing, pages 43-53

DOI: 10.5220/0002414300430053

Copyright

c

SciTePress

the Natural History Museum in London. Similarly throughout the wider world, there

have been numerous other research-led attempts to engage with museum visitors in a

context driven fashion.

At the University of Salford, the principal authors of this paper, we have a two

year project in collaboration with the Museum of Science & Industry in Manchester,

BT Group Archives and SETPOINT Greater Manchester. This project includes the

launch of a new and innovative communications gallery which celebrates the

evolution of communications and its impact on society. Within the new museum

gallery a wireless based information system called mi-Guide will be deployed. Per-

sonalisation of the mobile user experience is at the heart of this context driven appli-

cation. This project bridges the gap between that prior research and the desire to get a

real working product within a museum setting. This work was previously introduced

in Linge et al [3] and the link with previous research work was established. However

the focus of this paper is to extend the discussion presented there, and to launch mi-

Guide as a wireless context-driven museum guide.

2 Engaging with Museum Visitors

As the world’s first industrial city Manchester has been at the forefront of many in-

novations in communication including the early adoption of telegraphs and the tele-

phone, the exploitation of print - especially newspapers, the expansion of radio and

television and the invention of the modern programmable computer. MOSI is about

to launch a new communications gallery that is designed to inform the public about

this particular subject. It forms a key part of BT’s Connected Earth

1

– the first web

based museum project underpinned by a series of major physical collections distrib-

uted amongst a network of UK museums. The new gallery will offer visitors a jour-

ney through four themed zones including face-to-face communications, recorded

information and broadcasting. The gallery concludes with a future zone that is de-

voted to technology convergence and the post digital world.

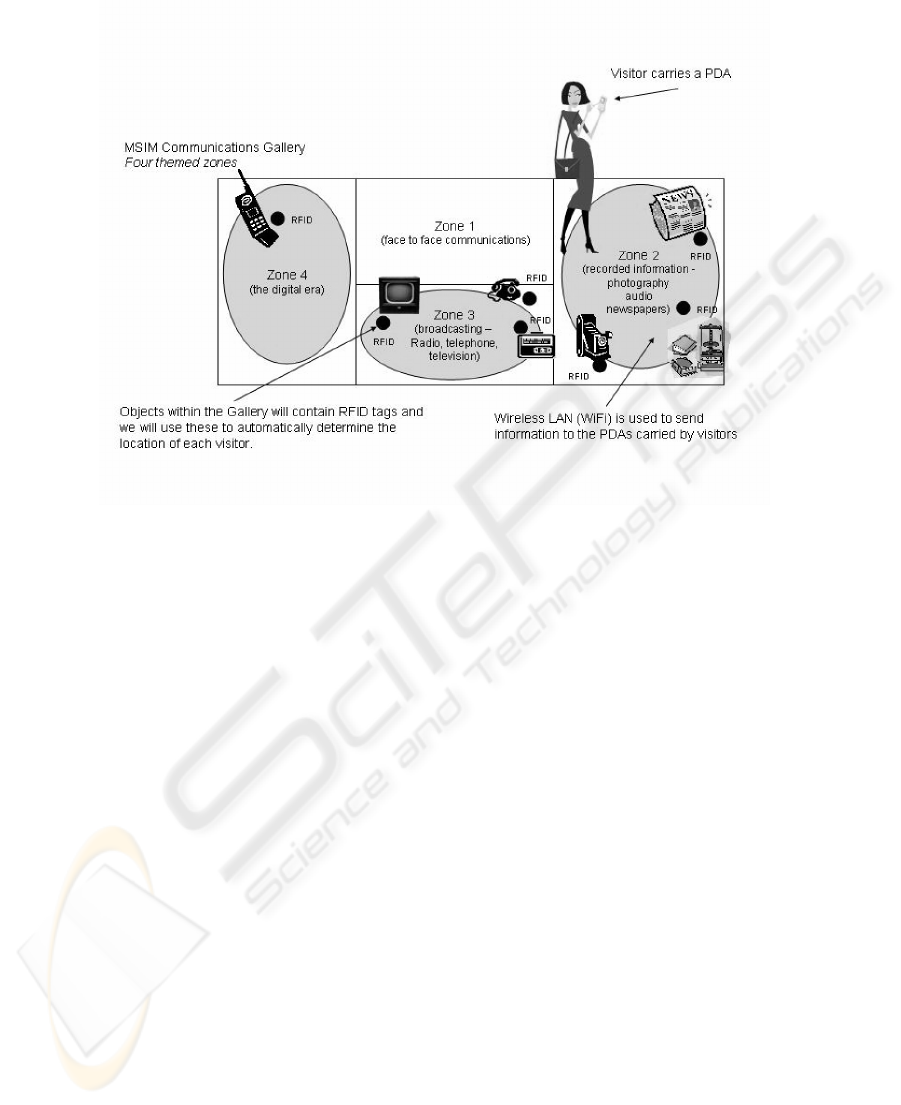

Mi-Guide is a context driven information system based on wireless communica-

tions which is intended to be deployed within the new gallery. This is to enable us to

create a new series of interactive educational experiences based on the user’s prox-

imity to the nearest exhibit. Visitors will be provided with a handheld device, in the

first instance a PDA, which is able to connect to a hybrid network comprising wire-

less LAN (WiFi) and either passive or active radio frequency identification (RFID)

tags. The WiFi network offers sufficient bandwidth to allow multimedia information

to be delivered in real time to each PDA whilst the RFID tags placed at key locations

and on selected exhibits around the gallery allow visitor location to be determined as

illustrated in figure 1.

1

www.connected-earth.com

44

Fig. 1. The Manchester Communications Gallery – Network Infrastructure.

The ability to locate a visitor, but more importantly to track their movements

through a gallery allows information to be delivered that is not only personalised to

the user but also intelligently adapts to the route that the visitor has chosen to take.

So, for example, going from exhibit A to exhibit C without seeing exhibit B can gen-

erate a different experience than if exhibit B had been visited. This is a key piece of

context for this system, here termed the exhibit history. Another important piece of

context is the user’s type or user profile. So for example, knowing that one PDA is

being used by a teacher allows information to be sent that will assist that teacher in

conducting their task. Mi-Guide is intended to provide an enhanced visitor experi-

ence for the museum allowing for additional content to be delivered using the full

capabilities of multimedia. In addition it will provide an ideal vehicle through which

to better engage with the visitors and to demonstrate the operation and function of

communications systems.

3 Context Driven Information Systems

Today’s mobile devices allow us to keep in touch whilst on the move and have even

changed the way that we communicate through facilities such as texting. However,

today’s mobiles are far more than just mere telephones or simple text devices. They

allow us to access the web, send and receive e-mail, play mp3s, run software applica-

tions, receive television and even make video calls. This exponential growth in mo-

bile communications is fuelled by ever more sophisticated attempts to personalise the

45

mobile user experience, all driven by a device that we will shortly have to re-term

‘the mobile computer’.

On top of this infrastructure, a future generation of multimedia based services is

beginning to be built. A key element of these new services is the ability to determine

location in the form of location based services, e.g. O

2

’s Streetmap service [4]. How-

ever, location is just one aspect of the wider concept of context, which derives from

the trend towards ubiquitous and pervasive computing. The term ‘ubiquitous com-

puting’ is generally first attributed to Mark Weiser [5] who in 1991 envisaged a world

in which computers would become all pervasive through mobile or embedded devices

interconnected through a ubiquitous network. Clearly this vision is not yet fully real-

ised but we are some of the way along the path towards that realisation.

However context suffers somewhat from being a vaguely defined concept. Ac-

cording to Mari Korkea-aho [6] context can be anything from identity, spatial infor-

mation, temporal information, environmental information, social situation, nearby

resources, availability of resources, human physiological measurements, activity,

schedules and agendas, and this list is by no means exhausted. Fortunately a compre-

hensive review in 2000 of the most prominent work to that date was carried out by

Dey and Abowd [7, 8] in which they attempted to define the terms context and con-

text awareness whilst introducing their pioneering work on the context toolkit. These

definitions are probably the most concise and well defined and have been used

throughout our work. They are as follows:

Context

: ‘Context is any information that can be used to characterise the

situation of an entity. An entity is a person, place or object that is considered relevant

to the interaction between a user and an application, including the user and the ap-

plication themselves’.

Context aware:

A system is context aware if it uses context to provide relevant in-

formation and / or services to the user, where relevancy depends on the user’s task’.

Dey and Abowd also proposed a hierarchy of contextual types and outlined a

method of categorising context aware applications. Identity, Location, Activity, and

Time are considered as the four primary context types which are then used to index

and define secondary context types. For example: given a person’s current location, a

secondary context type could be: where they have been or where they are going. This

hierarchy obviously has applications to defining a class structure of context types that

could be used in the development of context aware applications, or indeed a context

ontology, as was attempted in later papers by Strang and Linnhoff-Popien [9] and

Chou et al [12].

4 Context-Aware Museum Applications

There have been several attempts to enhance the museum experience with context-

aware applications. One of the early applications was GUIDE which was a web-

based system developed by the University of Lancaster and successfully deployed

46

across the City of Lancaster. Visitors linked with an information model of the city

using hand-held context-aware tourist guides. GUIDE used a cell-based 802.11 wire-

less LAN, covering the major tourist areas, to provide both positioning information

and deliver static and dynamic information to the mobile devices [10].

Imogl is a mobile guide that was deployed in two Belgian museums. Luyten and

Coninx [11] noted that in a museum setting, location has to be determined as prox-

imity to the nearest artefact because museum artefacts, although largely static, are apt

to be moved around over time. As the museums in questions both had outdoor ele-

ments, GPS was used to identify objects outdoors. However, as GPS can’t be used

indoors, Bluetooth was used instead. It is interesting to note that the authors identi-

fied that one of the main problems with Bluetooth in a museum setting is that its

communication range is too wide, suggesting IrDA as the likely best alternative.

Shih-Chun Chou et al in their 2005 paper [12] introduce us to a set of visitor-

oriented services which uses a semantic web rule reasoning engine (SWRE) to iden-

tify relevant sources of contextual information. This work is part of a collaboration

between Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh and the Institute for Information

Industry in Taiwan building on top of a comprehensive piece of work called the My-

Campus project [13, 14]. These services include exhibit recommendations, directions

to exhibits, people locator services and a rating application to share thoughts and

comments with other people. A user profile is built up at the start of the tour by get-

ting visitors to fill out a questionnaire. These user and privacy preferences are then

set in a semantic e-Wallet assigned to the user in order to tailor services accordingly.

Unfortunately this work is comprehensive but beyond our scope. A more useful

resource is that by Raptis et al who provide a review and comparison of other mobile

applications used within museum environments [15]. They also introduce a new

theoretical framework of context, which given that they concur with the view that

context is poorly defined seems counter-intuitive. Context is defined in four different

dimensions : the system, infrastructure, domain and physical contexts. It could be

argued that the first two of these relate directly to the software development cycle,

whereas the latter two are variations of identity, location and activity. Nevertheless

Raptis et al make a number of practical and salient points which are particularly ap-

plicable to museums. For example, in respect of observed museum visitor behaviour,

the most important factor affecting the interaction was felt to be the content itself and

not the technology, probably best summed up by the phrase “content is king”. An-

other important point made was the need to inform the user when something excep-

tional has occurred and give sensible instructions. This paper also includes a com-

parison of the technologies that affect the system context. It is interesting to note that

of the 12 systems reviewed, 11 of them opted for IrDA as their tagging solution and

that the other Imogl later moved from Bluetooth to IrDA.

5 Tagging Solutions

The mi-Guide application will be delivered in the first instance via PDAs, although at

a later date other devices may come into play. The basic idea is that exhibit informa-

tion is pulled onto the user’s device as the user approaches. In order to achieve this,

47

the PDAs require a means of detecting their proximity to the nearest exhibit. This is

anticipated to be some form of tag that is detectable from the PDA. In the first ver-

sion of mi-Guide this will be a passive RFID tag (Phillips I-Code 2 tags, ISO15693

standard, 13.56 MHz). The passive tags are energised from a Socket Communica-

tions RFID reader which slots into the PDA. Passive tags have no power of their own

and are thus dependent on the power of the energising device. As the RFID reader is

designed to operate at minimal power to save drainage on the PDA battery, the tags

can only be read from 6.35 cm as opposed to the maximum quoted range for these

tags (1.5m). This first version of mi-Guide therefore is in keeping with a ‘scanner

metaphor’, as expressed by Raptis et al.

Active tags on the other hand have their own source of power and therefore have a

much greater read range. Using active tags, a device can poll for tags within a given

radius and information can be pushed onto the devices, which fits with Raptis et al’s

‘remote control metaphor’. Possible active tag technologies are WiFi, Bluetooth or

IrDA. These have the advantage that they are built into the Dell Axim PDAs that we

use in the mi-Guide system. Apart from cost, the main disadvantage with active tags

is that the read range of these tags is in fact too good. It is difficult to achieve the

granularity that is required in a museum environment. In order to be able to distin-

guish different exhibits accurately, a read range of the order of a metre is required,

otherwise there is overlap between the tags and it is not possible to determine which

is the nearest. Alternatively the reader itself would need to be able to distinguish

which is the nearest tag, a purpose for which most RFID readers are not designed.

There are commercial systems that can accurately determine location to within 3-5

metres. These systems tend to be aimed at large markets such as asset management in

hospitals where the large costs can be justified. Location is determined by triangula-

tion of the WiFi signal strength and/or a differential time of arrival algorithm from

three or more different access points using WiFi tags. An example of such a product

is the Ekahau positioning engine, which is indeed used primarily in the healthcare

industries [16]. Similar high-end systems are Aeroscout [17] and Wherenet [18].

In a sense the mi-Guide system is doing the opposite from most tagging systems.

In most systems, the asset is mobile and its whereabouts are tracked or monitored.

This is the case in hospital asset management systems, similarly back-end production

systems such as those deployed in retail or manufacturing where RFID is used to keep

track of the movement of goods. However, in our case the asset is static (the mu-

seum exhibit) and the tracking devices (the PDAs) are mobile. In addition the pur-

pose of most RFID readers is to detect every tag within its range so that assets are not

missed in the tracking systems, again the opposite of our requirements.

6 The mi-Guide System Architecture

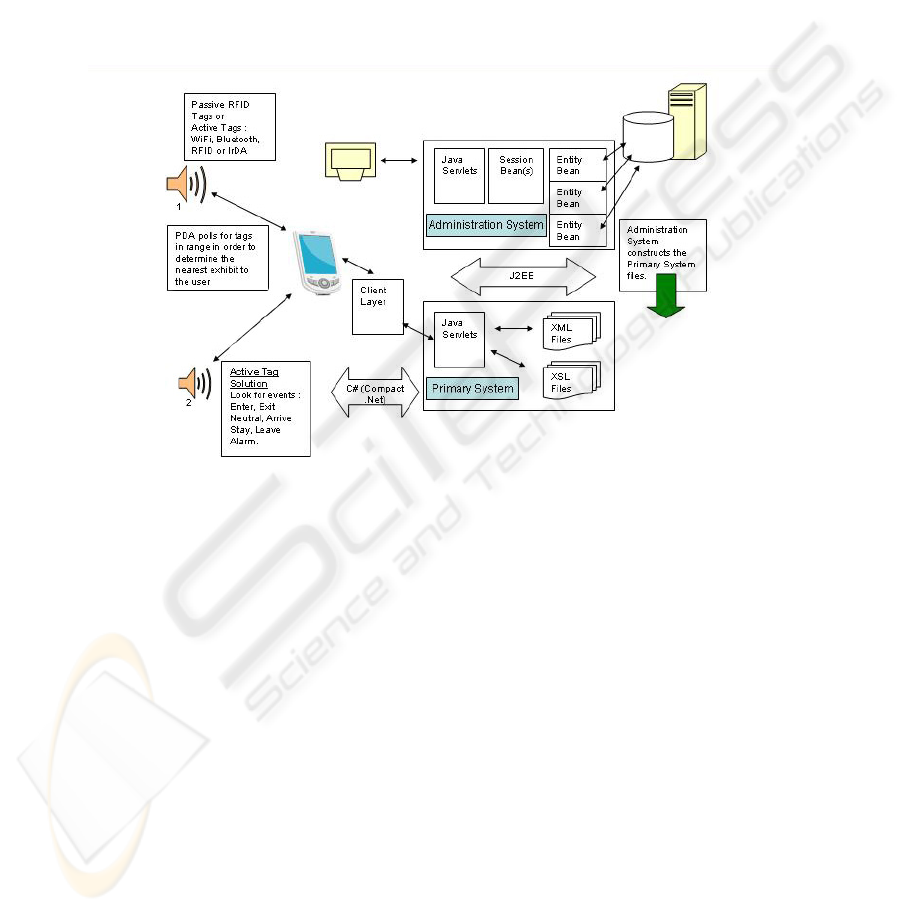

The diagram in figure 2 gives an overview of the mi-Guide system architecture. The

primary mi-Guide system (Primary System) which is delivered to the mi-Guide PDAs

is a client-server web application which consists of a client-side C# application and a

server-side Java application. The latter resides on a Sun Java System Application

Server and comprises a number of Java servlets working in conjunction with a set of

48

xml files and their associated xsl files. The client-side application wraps around a

web browser (Pocket Internet Explorer) embedded inside the application, which is

then used to access the server-side web application.

The client is written in C# as this is better supported on the Pocket PCs that are used

on the project in the form of the (Microsoft) Compact .Net Framework. For example,

at the time of project commencement, there was limited support for the Java alterna-

tive, J2ME (Java 2 Micro Edition). It was also clear early on in the project that it

would not be possible to offer mi-Guide as a download to visitors’ personal PDAs.

This was because there is insufficient standardisation of the functionality that PDAs

carry such as a wireless connection (WiFi), rather instead there would need to a stan-

dardised set of PDAs (Dell Axims) which would be issued to visitors by the gallery.

Fig. 2. The mi-Guide System Architecture.

The purpose of the xml files is to allow a more simplified description of the informa-

tion related to each exhibit. A single RFID tag (or equivalent active tag) can suffice

for one exhibit, and the content related to that exhibit is sub-divided into sections, as

specified by the museum. Alternatively a tag can relate to multiple exhibits and the

user is given a choice as to which they wish to choose. Content is hierarchically

structured as shown in figure 3. From the home page the visitor can scan the PDA at

a mi-Guide scan point (RFID tag). Depending on which exhibit is tagged, the content

for that exhibit and its related information will then be delivered. Each section has an

associated audio clip to describe the content on view, together with a section image

and a relevant caption. In addition it may be possible to link to extra media files such

as video and further audio clips or additional images that the museum might want to

display related to the exhibit. All of this information is contained within the xml files

for which a purpose built xml dialect was constructed, together with an associated

document type definition (dtd) that describes this dialect.

49

Fig. 3. mi-Guide Screen Shots.

This xml must also be ‘marked up’ according to the user’s type, e.g. adults and chil-

dren, as well as more specific classifications such as teacher and pupil. In addition,

the user’s progress through exhibits and any missed exhibits (exhibit history) will be

recorded as part of the system’s overall context. Appropriate adaptation to this con-

text will be added to the system as part of the next phase of mi-Guide.

A system administration function will also be provided that is able to maintain the

information in the xml files in a user-friendly fashion. This will also allow the infor-

mation delivered about an exhibit to be structured for each given user type. The al-

ternative approach of constructing information from relevant database tables could

result in exhibit information where the joins between the constituent information can

be seen, giving the impression of a story that is ‘clunky’ and doesn’t flow. This re-

lates back to one of the key findings of our previous research, which was concerned

with building context into workflow process models, i.e. the requirement for addi-

tional advanced workflow tasks as user expertise increases [19, 20].

The other main advantage of xml files is that they are associated with appropriate

xsl stylesheets so that the xml data can be transformed into html pages for the client-

side web browser. This is achieved by parsing the xml with a JDOM parser [21] and

converting the data in real time to the appropriate device using an xslt transformation.

As client side device information available to the web browser is fairly limited, this

relies on the system knowing what devices it supports by picking up its device id and

the applicable xsl file. The system currently just supports the PDAs, but it would be

possible to support new types of devices in the future with only the addition of a set

of device-specific xsl files.

The plan is to adopt a hybrid of a conventional relational database management

system and the xml/media files. The back-end database is needed to store the data

that will allow the administration functions to be performed such as maintaining the

inventory of exhibits and the lists of media files. The intention is to use the database

as the master data store from which the xml files are constructed. The media files

will eventually be streamed using Windows Media Server and delivered to the PDAs

50

as embedded windows media files. Therefore these will also need to be set up cor-

rectly. The system administration function will be available as a later release of mi-

Guide and will be accessible when the system is off-line.

7 Implementation

At the time of writing the mi-Guide application is nearing the completion of phase 1

of the implementation. This comprises the basic application which is able to act as an

enhanced wireless visitor guide for the new communications gallery so that we are

able to launch in Summer 2007. Phase 2 will contain the administration system, user

logging and any context-aware enhancements that are deemed practical for the mu-

seum environment within the time frame left on the project. Successful demonstra-

tions of the phase 1 application have been carried out in the laboratory environment

as well as a test to ensure that the client application swaps successfully between wire-

less access points as the user roams between WiFi zones.

We are now about to move into a system testing period within the museum envi-

ronment for phase 1. Beyond that we anticipate that there will be a period of the

order of six months of user acceptance testing in the form of a user trial. The mi-

Guide application will be offered to a limited numbers of visitors per day in order for

them to evaluate the product and to identify any problems that might arise.

From our experience of the implementation process within the laboratory environ-

ment, we anticipate that any problems would most likely occur in the PDAs ability to

robustly connect to the wireless infrastructure. Indeed this seems to have been the

case in other similar museum applications. Other anticipated issues relate to users

deliberately aiming to willfully bring down the application or cause problems within

the PDA environment. Finally security of or damage to the PDAs is also likely to be

of concern.

However the main purpose of the system testing & user trial periods is to thor-

oughly test these issues in the museum environment in order that we are able to pro-

ceed with confidence at a later date to a full product. This product can then be further

enhanced by context-aware features such as user tracking and tailoring of content to

different types of individual.

8 Summary

This paper has presented ongoing work into the development of a context driven

wireless information system for deployment within a museum environment. Our

application called mi-Guide provides a novel architecture combining a PDA user

interface with WiFi and passive RFID tagging giving access to a server-side multi-

media web application. In this way the user’s context (user type and location) is

translated into real-time delivery of relevant content to visitors. Such a system sig-

nificantly advances conventional museum paradigms and offers new opportunities for

visitor access to museum collections.

51

Further planned developments of the mi-Guide system will expand the context

gathering capability such that it is fully realised as a context-aware application.

Therefore later enhancements will firstly include visitor tracking which in turn allows

content to be delivered and manipulated to reflect a visitor’s journey through the

gallery. Secondly the system will differentiate between users to distinguish between

adults, teachers, pupils etc., and deliver information that is appropriate to them. The

system will be further enhanced with the addition of a system administration function

which will be needed to provide maintenance to the file systems over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council

(EPSRC) who have funded this work as grant EP/D504686/1 within their Partner-

ships for Public Engagement programme.

References

1. N.X.P., I-CODE enables museum visitors to take their memories home, March 2004.

[Online] Available from : http://www.nxp.com/news/identification/articles/success/s86/

[Cited 08/02/2007]

2. Guide ID., Guide ID – your mobile information guide, © 2006. [Online] Available from :

http://www.vepon.nl/NavMain.asp [Cited 08/02/2007]

3. Linge, N. et al., Context Driven Information Systems for Museum Visitors. In PGNet

2006, 7

th

Annual Postgraduate Symposium on The Convergence of Telecommunications,

Networking & Broadcasting. 2006. Liverpool John Moores University.

4. 0

2

Streetmap. [Online] Available from : http://www.streetmap.co.uk/o2.htm [Cited

05/02/2007]

5. Weiser, M., The Computer for the 21st Century. Scientific American, 1991. 265(3): p. 94 -

104.

6. Korkea-aho, M., Context-Aware Applications Survey. 2000, Department of Computer

Science, Helsinki University of Technology. [Online] Available from :

http://www.hut.fi/~mkorkeaa/doc/context-aware.html [Cited 09/02/2007]

7. Dey, A.K., Understanding and Using Context. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 2001.

5(1): p. 4-7.

8. Dey, A.K. and G.D. Abowd. Towards a better understanding of context and context-

awareness. in CHI 2000, Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2000. The

Hague, The Netherlands

9. Strang, T. and C. Linnhoff-Popien. Service Interoperability on Context Level in Ubiquitous

Computing Environments. in International Conference on Advances in Infrastructure for

Electronic Business, Education, Science, Medicine, and Mobile Technologies on the Inter-

net. 2003. L'Aquila, Italy.

10. Cheverst, K. et al., Exploiting Context to Support Social Awareness and Social Navigation.

ACM SIGGROUP Bulletin, 2000. 21(3): p. 43-48.

11. Luyten, K. and Coninx K., Imogl : Take Control over a Context-Aware Electronic Mobile

Guide for Museums. HCI in Mobile Guides, 2004. University of Strathclyde, Glasgow,

UK.

52

12. Chou, S-C. et al., Semantic Web Technologies for Context-Aware Museum Tour Guide

Applications. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Advanced Information

Networking and Applications - Volume 2, pp 709–714, 2005. IEEE Computer Society,

Washington D.C., USA.

13. Miller N. et al, Context-Aware Computing using a Shared Contextual Information Service.

“Hot Spots”, Pervasive 2004, April 2004, Vienna. Advances in Pervasive Computing, Aus-

trian Computer Society (OCG), ISBN 3-85403-176-9.

14. Hengartner U. and Steenkiste P., Access Control to Information

in Pervasive Computing Environments. Carnegie Mellon University. [Online] Available

from : http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~uhengart/hotos03/index.html [Cited 09/02/2007]

15. Raptis D. et al., Context-based Design of Mobile Applications for Museums: A Survey of

Existing Practices. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Volume 111, pp

153–160, 2005. ACM Press, New York, USA.

16. Ekahau, © 2000-2007 Ekahau, Inc. [Online] Available from http://www.ekahau.com/

[Cited 06/02/2007]

17. AeroScout Enterprise Visibility Solutions ®, [Online] Available from

http://www.aeroscout.com/ [Cited 06/02/2007]

18. WhereNet, [Online] Available from http://www.wherenet.com/ [Cited 06/02/2007]

19. Bates, D., Linge, N. Ritchings, T., Chrisp T., 2003. Designing a Context-Aware Distributed

System – Asking the Key Questions. In Proceedings of the 2

nd

IASTED International Con-

ference on Communications, Internet and Information Technology. Scottsdale, Arizona,

Nov 17-19

th

2003. pp 361-371.

20. Bates, D., Linge, N., Hope M., Ritchings T., 2004. A Proposed Model for a Context Aware

Distributed System. In IWUC 2004, 1

st

International Workshop on Ubiquitous Computing,

Porto, Portugal, April 13

th

-14

th

2004, pp 180-194.

21. jdom.org, JDOM, 2000-2006 [Online] Available from http://www.jdom.org/ [Cited

12/02/2007]

53