DIFFERENCES IN PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO THE

INTENSITY OF MENTAL STRESS

Chi’e Soga, Chikamune Wada

Graduate School of Life Science and Systems Engineering, Kyushu Institute of Technology

2-4 Hibikino, Wakamatsu-ku, Kitakyushu, Fukuoka, 808-0196, Japan

Shinji Miyake

University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan

1-1 Iseigaoka, Yahatanishi-ku, Kitakyushu, Fukuoka, 807-8555, Japan

Keywords: Autonomic nervous system, RRI, plethysmogram, skin potential level, blood pressure, mental workload.

Abstract: It is widely understood that mental stress produces various physiological changes. Though the relationship

between mental stress and physiological response has been extensively reported, few reports have tried to

clarify the relationships between various physiological responses and the intensity level of stress. In this

study, we investigated autonomic nervous system activities to find a physiological index based on which we

can evaluate the intensity of mental stress. As a result, we found that there were different response patterns

for each physiological index. We consider that each physiological index shows different feelings and/or

situations related to mental stress.

1 INTRODUCTION

In our country, the increase in psychiatric disorders,

such as depression and schizophrenia, is noted. The

number of suicides per year has been steadily high in

recent years, with more than 30,000 people a year

since 1998. This increase in psychiatric disorders

and high rate of suicide are serious problem in

Japan.

It is believed that these daily stresses play a role

in a

number of psychiatric disorders. If we can

evaluate daily stress quantitatively and determine

our own or other people mental state, this could

contribute to the prevention of various diseases

caused by mental stress.

It is widely understood that physiological

chan

ges induced by mental stress are related to the

autonomic nervous system, and can affect the heart

rate, blood pressure and plethysmogram. The

relationship between mental stress and physiological

feedback has been extensively reported (Takatsu et

al., 2000, Mishima, Kubota and Nagata, 1999).

We also consider that establishing a quantitative

ev

aluation method for mental stress will help

prevent diseases caused by mental stress. It is

necessary to examine the intensity of stress to realize

a quantitative evaluation of mental stress. However,

few reports have tried to clarify the relationships

between physiological responses and the intensity of

stress. In this paper, we investigated the autonomic

nervous system activity in the three conditions for

the intensity of mental stress.

2 METHOD

We used a mental arithmetic task as the mental

workload and measured the physiological and

subjective responses.

2.1 Task

A target three-digit number, several two-digit

numbers and an OK button were displayed on a

computer screen. The participants

were required to

select th

e combination of three two-digit numbers

whose sum is equal to the target number and click

the OK button.

Whenever a participant clicked the

298

Soga C., Wada C. and Miyake S. (2008).

DIFFERENCES IN PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO THE INTENSITY OF MENTAL STRESS.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing, pages 298-301

DOI: 10.5220/0001069702980301

Copyright

c

SciTePress

OK button, the sum of the selected numbers was

shown on the screen. If the sum was equal to the

target number, the next arithmetic question was

displayed. The participant could choose different

combinations of numbers until the right one was

chosen. The elapsed time and the number of correct

answers were also displayed on the screen. The task

screen is shown in Figure 1.

The three conditions were used for the intensity

of mental stress. The conditions were as follows:

TASK1 (High level): The number of

two-digit

number is ten.

TASK2 (Medium level): The number of

two-

digit

number is eight.

TASK3 (Low level): The number of

two-digit

number is five.

Figure 1: Mental arithmetic task screen of high level.

2.2 Physiological Measurements and

Subjective Assessment

We measured the electrocardiogram (ECG),

plethysmogram (PTG), blood pressure (BP), tissue

blood pressure (TBV) and skin potential levels

(SPL). These signals were recorded in a PC at a 1-

kHz sampling rate. Also, stroke volume (SV) and

cardiac output (CO) were obtained every heartbeat.

The R-R interval (RRI), LF/HF ratio, systolic

blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure

(DBP), mean blood pressure (MBP=DBP+(SBP-

DBP)/3), baroreceptor reflex sensitivity

(BRS=square root of (LF of SBP/LF of RRI)),

amplitude of the PTG and total peripheral resistance

(TPR=MBP/CO) were calculated.

The National Aeronautics and Space

Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX),

Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the semantic

differential method (SD method) were used to obtain

the subjective responses.

The NASA-TLX is a widely used subjective

workload assessment technique (Hart and Staveland,

1988). The WWL value was calculated. The POMS

consists of 65 adjectives and assesses six mood

states dimensions. We used 24 adjectives related to

Tension-Anxiety (TA), Vigor (V) and Fatigue (F)

for reducing the participant’s burden. The SD

method comprising seventeen items was used to

assess the participants’ emotions.

2.3 Procedure

The participants were familiarized with what to

expect during the task before the start of the

experiment. Each participant underwent the

experiment procedure once.

The experimental procedure was as follows:

1. Rest1 (6 min: PRE1)

2. High level arithmetic (6 min: TASK1)

3. POMS, NASA-TLX and SD method

4. Rest2 (6 min: PRE2)

5. Medium level arithmetic (6 min: TASK2)

6. POMS, NASA-TLX and SD method

7. Rest3 (6 min: PRE3)

8. Low level arithmetic (6 min: TASK3)

9. POMS, NASA-TLX and SD method

10. Rest4 (6 min: POST)

The participants were instructed to provide at

least fifteen correct answers in six minutes and not

to give up until the six-minute run was finished. If

the participants completed the task (i.e. gave the

minimum number of correct answers) before the

deadline, they were required to continue giving

correct answers. After six minutes, the run was

finished, and the participants were asked to cease the

mental arithmetic activity even if they had not

completed the task. The number of correct answers

was displayed on the screen to let the participants

know when the task was completed.

2.4 Participants

Sixteen healthy male graduate students aged 21 to

32 (average: 23.8 yrs.) participated in this study. All

participants gave their written informed consent.

DIFFERENCES IN PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO THE INTENSITY OF MENTAL STRESS

299

3 DATA ANALYSIS

3.1 Statistical Analysis

The data were divided into seven 6-minute blocks

(PRE1, TASK1, PRE2, TASK2, PRE3, TASK3 and

POST). All parameters were standardized for each

participant.

The results were analyzed by repeated

measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) using

SPSS 11.0J. The degree of freedom was adjusted

using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. Tukey’s

honestly significant difference (Tukey’s HSD) test

was used in the post-hoc analysis.

3.2 Subjective Assessment

Three factors (FACTOR1, FACTOR2 and

FACTOR3) were obtained from the seventeen items

of the SD method using Factor Analysis. The factor

scores, NASA-TLX scores, POMS scores and all

physiological indices were standardized for each

participant. The correlation coefficients of 48 pairs

of subjective assessments and physiological indices

were calculated.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Differences in Physiological

Response

The WWL value of Task3 was significantly low

(p<0.05). The results of the multiple comparison

revealed that there were no significant differences in

WWL value between Task1 and Task2. This result

indicated that the condition of Task3 was simpler

than the conditions of the other two tasks.

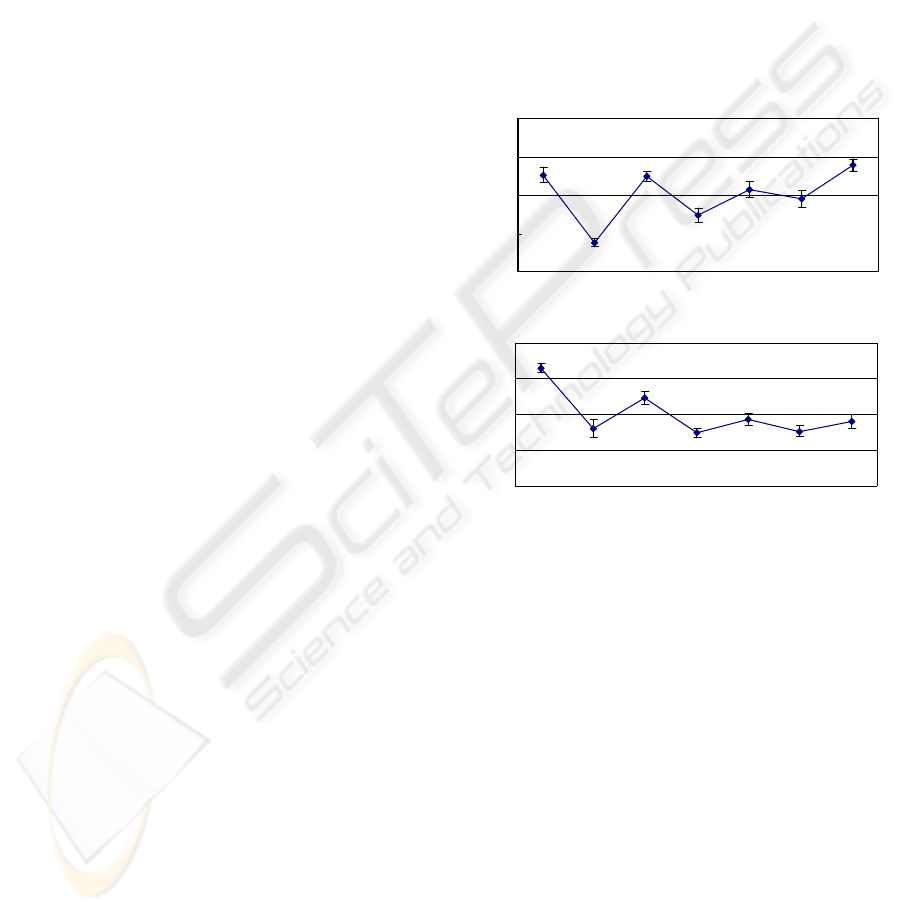

There were two patterns for each physiological

response in both different cases: task periods and the

resting periods. Figure 2 shows the averages of the

SPL and the amplitude of the PTG for all the

participants. Both parameters were significantly

lower in TASK1 and TASK2 comparing with resting

periods. The SPL values indicated that the changes

during the task were smaller when the difficulty

level became low. The RRI, SBP, DBP, BRS and

TPR showed a tendency similar to that of the SPL.

The amplitude of the PTG indicated that the

responses after the completion of the task (during

rest) were smaller when the difficulty level became

low. The TBV, CO and SV showed a tendency

similar to the amplitude of the PTG. There was no

discernible tendency in the LF/HF ratio.

In a previous study, we found that there were

different recovery patterns for each physiological

index (Soga, Miyake and Wada, 2007). In this study,

there were also different recovery patterns for the

various physiological indices. These results suggest

that each physiological response corresponds to

different feelings and/or situations. A difference in

response during the task might correspond to

“Executing task” and the feeling of “Tension.” A

difference in response after the task might

correspond to “Task performance” and the feeling of

“Regret.”

-2

-1

0

1

2

PRE1 TASK1 PRE2 TASK2 PRE3 TASK3 POST

Standardized Scor

SPL

e

-2

-1

0

1

2

PRE1 TASK1 PRE2 TASK2 PRE3 TASK3 POST

Standardized Scor

Amplitude of PTG

e

Figure 2: The average changes in the physiological

responses for each block. The bars indicated the standard

errors of the mean.

4.2 Correlation Coefficient between the

Subjective Measurements and the

Physiological Indices

There were significant correlation between the

FACTOR1 score and the DBP (r=-0.340; p<0.05),

MBP (r=-0.312; p<0.05) and SPL (r=0.506;

p<0.001). There were significant correlation

between the FACTOR2 score and the SPL (r=0.322;

p<0.05). The FACTOR3 score significantly related

to the SBP (r=-0.350; p<0.05), DBP (r=-0.378;

p<0.05), MBP (r=-0.364; p<0.05), BRS (r=0.415;

p<0.01), RRI (r=0.433; p<0.01) and SPL (r=0.312;

p<0.05). The FACTOR1 consisted of the following

items: “Difficult-Easy,” “Troublesome-Smooth,” “I

felt the task duration was short-I felt the task

duration was long,” etc. Therefore we consider that

BIOSIGNALS 2008 - International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

300

the FACTOR1 relates to the degree of difficulty of

the task. The FACTOR2 consisted of the following

items: “Dislike-Like,” “Boring-Interesting” and “I

want to execute the task-I don’t want to execute the

task.” The FACTOR3 was as follows: “Respond

randomly-Respond after proper calculation.” We

consider that the FACTOR2 relates to the

participants’ concentration and the FACTOR3

relates to the participants’ attitude.

The NASA-TLX revealed that there were

significant correlation between the TD and SPL (r=-

0.676; p<0.001), and the OP and the amplitude of

the PTG (r=-0.324; p<0.05). The POMS showed that

there were significant correlation between V and the

SPL (r=-0.381; p<0.05), and F and the amplitude of

the PTG (r=-0.308; p<0.05).

Although some physiological indices seemed to

correlate with the subjective assessments because

the correlation values were small, there were only

three blocks for standardization, and all the data

were pooled. At least, we consider that each

physiological response corresponds to different

feelings and/or situations. This suggests that the

classification of physiological responses according

to the results of the subjective assessment is helpful

in investigating the complex information contained

in each physiological index. In our past study, we

found that the SPL related to the time pressure (Soga,

Miyake and Wada, 2007). In this study, the SPL

results showed a tendency similar to that found in

our past study. Therefore we consider that the SPL is

a sensitive index for the estimation of mental stress.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We found that there were two patterns for each

physiological response of the autonomic nervous

system during the task periods and the resting

periods at three different difficulty levels (high,

medium and low). Significant difference in PTG

amplitude between task and after task resting period

was disappeared in the last two blocks (TASK3 and

POST). In addition, we found that there were

significant correlation between the physiological

changes and the subjective assessments.

These results suggest that each physiological

response corresponds to different feelings and/or

situations related to mental stress. Further

experiment should be done to confirm this result.

Our final aim is to establish a quantitative evaluation

method for mental stress.

REFERENCES

Hart S H. and Staveland L. E., 1988. Elsevier Science

Publishers B.B., pp.139-183, Amsterdam Development

of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Result of Empirical

and Theoretical Research, In P. A. Hancock and N.

Meshkati (eds.), Human Mental Workload.

Mishima N, Kubota S and Nagata S, 1999. Psychotherapy

and Psychosomatics, Vol.68, No.4, 207-213,

Psychological correlates of relaxation induced by

standard autogenic training.

Soga C, Miyake S, Wada C, 2007. SICE Annual

Conference 2007, 1366-1371, Recovery patterns in the

physiological responses of the autonomic nervous

system induced by mental workload.

Takatsu H, Munakata M, Ozaki O, Yokoyama K,

Watanabe Y and Tanaka K, 2000. T.IEEE Japan,

Vol.120-C, No.1, 104-110, An evaluation of the

quantitative relationship between the subjective stress

value and heart rate variability (in Japanese).

DIFFERENCES IN PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO THE INTENSITY OF MENTAL STRESS

301