STUDYING USERS’ ACCEPTABILITY TOWARDS 3D IMMERSIVE

ENVIRONMENTS

Virtual Tours: A Case Study

Karina Rodriguez Echavarria, Craig Moore, David Morris

Watts Building, Moulsecoomb University of Brighton, Brighton, U.K.

David Arnold, A. Delaney, R. Heath

Watts Building, Moulsecoomb University of Brighton, Brighton, U.K.

Keywords:

Museum Experience, Acceptability, User Interfaces, Interaction techniques.

Abstract:

If information is considered the key in today’s information society, then museums and heritage sites are of

critical importance as they are places for knowledge to be shared and experienced by individuals. For this

reason, presenting and distributing information through ICT forms could play a critical role for the museum

in order to empower the public in their understanding of the past. The view of using ICT contextualisation

mechanisms, such as 3D immersive virtual environment, in museums and heritage sites is explored in this re-

search. Hence, this paper describes efforts towards exploring the acceptability of the interfaces and interaction

techniques for Virtual Tours. We acknowledge the difficulty of the task as 3D immersive environment do not

have defined interfaces nor visitor are believed to have replicable experiences. However, we believe that a

significant amount of studies of this type might provide some answers to a field full of expectations but not

enough experience in the ICT field.

1 INTRODUCTION

The exhibition in a museum or heritage site is mainly

a visual environment - both the objects or spaces and

their communication forms - for the visitor to de-

ploy their own interpretative strategies. According to

museums theory, visitors bring a multiplicity of dif-

ferent attitudes, expectations and experiences to the

reading of an exhibition display, so that their com-

prehension of it is individualized. Hence, visitors fo-

cus on those aspects which they are able to recog-

nize and thereby grasp both visually and conceptu-

ally. (Hooper-Greenhill, 2000) states that the use of

senses, followed by observation, reflection and de-

duction, and finally the placing of the observation

and ideas within a contextual framework, remains the

standard method used for object teaching within the

heritage places today.

(Falk and Dierking, 1992) studies have demonstrated

that visitors tend to be very attentive to objects and

spaces and only occasionally to text labels to acquire

further knowledge which can inform their interpreta-

tion. Thus, the relationship between both the objects

and the communication form is critical, as the latter

provides additional meaning, in case this is needed,

for the visitor to construct his/her own interpretation

of the artefact and to fully understand the narrative.

Failure to include or achieve an effective communi-

cation form could mean the visitor will be unable to

make any sense of the exhibition display. (Vergo,

2000) highlights that the attitude that objects on dis-

play were best left to speak for themselves persisted

until well into the nineteen century and to some ex-

tent it is still with us today. Although, almost all

agree that exhibitions address themselves to an audi-

ence, and that their aim is, in the broadest term, edu-

cational; opinions diverge widely as to how that aim

is best achieved. In particular, there is disagreement

over the question as to the level of information or ex-

plication appropriate or desirable in the context of a

given exhibition.

Much of this confusion is attributed to the tendency to

treat as synonyms the words “learning”, “education”

and “school”. One manifestation of this confusion is

the idea that learning is primarily the acquisition of

new ideas, facts or information; rather than the con-

solidation and incremental growth of existing ideas

and information (Falk and Dierking, 1992). This

477

Rodriguez Echavarria K., Moore C., Morris D., Arnold D., Delaney A. and Heath R. (2008).

STUDYING USERS’ ACCEPTABILITY TOWARDS 3D IMMERSIVE ENVIRONMENTS - Virtual Tours: A Case Study.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications, pages 477-484

DOI: 10.5220/0001100404770484

Copyright

c

SciTePress

causes confusion among concepts of learning cogni-

tive information (facts and concepts), learning affec-

tive information (attitudes, beliefs and feelings), and

learning psychomotor information (i.e. how to focus

a microscope). Learning, many believe, refers only to

learning cognitive information, which unfortunately

is only one limited dimension as what visitors obtain

from an actual museum visit.

Regarding the question of which level of information

is required, two polarized views divide the spectrum

of opinions; although, exhibitions always achieve

an intermediate point or compromise between them.

These are (Vergo, 2000):

1. The ‘aesthetic exhibition’ - where the object itself

is the most important. Artefacts are not supposed

to be understood but ‘experienced’; however, this

private process is not very well defined. In this

view, any kind of communication form is an in-

trusion into the ‘what is supposed to be’ a silent

contemplation of the artefact.

2. The ‘contextual exhibition’ - where the objects

and spaces themselves are tokens of a particular

age, a particular culture, a particular political or

social system, or representative of certain ideas or

beliefs. The argument for this contextualisation is

that for the uninformed eye, the fragments of other

times and other cultures, removed from their orig-

inal context settings and rituals, are mere curiosi-

ties made by unknown people which value can-

not be appreciated (Wright, 2000). In such exhi-

bitions objects and spaces coexist, sometimes un-

easily, with other kinds of communication forms.

Until now, much of it in textural form.

It is the latter view which is of interest for the Infor-

mation and Communication Technology (ICT) field.

If information and knowledge is considered key in

today’s information society, then museums and her-

itage sites are of critical importance as they are places

for knowledge to be shared and experienced (Wright,

2000). Hence, presenting and distributing informa-

tion through ICT forms could play a critical role for

heritage organizations in order to empower the pub-

lic in their understanding of the past, but most impor-

tantly of the present.

As such, communication forms based on ICT provide

the capacity of using a mixture of predominantly non

textual material for contextualizing the objects and

places in display. Although, the advantages of do-

ing this has been previously suggested, the accept-

ability and the selection of user interfaces and inter-

action techniques (in software and hardware) for their

use have not yet been completely identified. This

work attempts to provide some answers to these ques-

tions. In particular to explore the use of 3D interactive

virtual environment in a Virtual Tour application for

contextualizing historical cities. As such, the paper

describes efforts towards evaluating the acceptability

of the interfaces using usability methodologies to ex-

plore not only the perceived opinions and responses

of users, but also their behavior. We acknowledge

the difficulty of the task as 3D immersive environ-

ments do not have defined interfaces nor visitor are

believed to have replicable experiences. However, we

believethat a significant amount of studies of this type

combined with general guidelines in the usability field

might provide some answers to a field full of expecta-

tions but not enough experience in the ICT field.

2 VIRTUAL TOUR: XVII

CENTURY WOLFENBUTTEL

The Virtual Tour application used for this research

recreates Wolfenbuttel as it once stood during the

seventeen century. The town sits on the Oker river in

Lower Saxony, just a few kilometres south of Braun-

schweig. Wolfenbuttel became the residence for the

dukes of Brunswick in 1432 and in the following

three centuries the town was an important centre of

the arts. The 3D virtual environment reconstructs the

town by using the main buildings from this period,

such as the ducal palace, the library and the armoury,

as well as a few other areas of interest. Nowadays,

the town of Wolfenbuttel still contains many of these

buildings; although their functionality has completely

changed. In the real place, visitors can walk through

the small streets appreciating the beauty of the

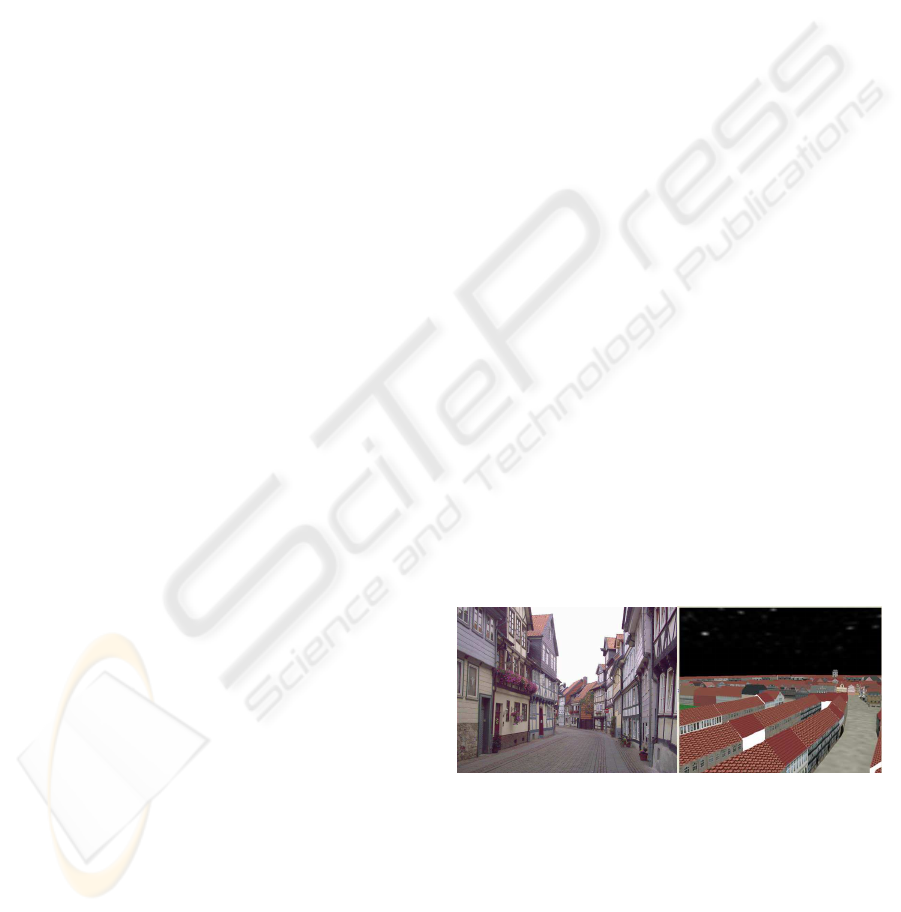

historical buildings (see figure-1).

For this research, our premise was that only looking

Figure 1: Recreation of streets in the Town Wolfenbuttel.

at the buildings (in the real or in the non-real envi-

ronment) was not enough for a visitor to understand

the historical importance of the place. Hence, the

main purpose of the virtual tour was to contextualize

the buildings and spaces of the city by providing

additional information on their relevance for the

town. For this, a female virtual avatar populates the

environment acting as a tour guide. This was in-

cluded with the intention of creating a more engaging

GRAPP 2008 - International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

478

presentation of the information about the town.

The Graphical User Interface (GUI) of the application

has different sections (see figure-2). Six locations

have been selected for the user to visit in the virtual

reconstruction. The user navigates from one to

another by clicking on labels ‘floating’ in the sky

in the “Navigation Panel”. Once at a location, the

user can look around, rotating the view by using

the mouse. Free movement is possible only with

keys commonly used in first-person shooter games

(i.e. Counter Strike). The ‘floating’ labels have been

arranged according to the geographical location of

the user in the 3D space. As such, when positioned at

any location, the labels for the places to the east/west

and north of the current location will appear bigger

and clearer, highlighting the fact that to go to another

location it is first necessary to pass through the neigh-

bouring locations. The “Location Panel” highlights

the name of the location the user is currently located.

The user can request more information about any

of the six locations in town using the following

approaches: i) typing a question on the “Free-Type

Questions Panel” or ii) ‘pointing&clicking’ on one

of the predefined questions in the “Frequently Asked

Questions Panel”. The user also has access to a

webpage when arriving at certain locations.

Figure 2: Graphical User Interface (GUI) of 3D immersive

application for CH.

3 METHODOLOGY OF THE

STUDY

The aim of the study was to explore individuals re-

actions to the interfaces and interaction techniques as

well as the acceptability of the specific Virtual Tour.

Further issues the research was interested in address-

ing were:

• Enjoyment, engagement and understanding of the

historical material presented by an individual user.

• Usefulness of including virtual avatars in the en-

vironment.

• Learning curve for using the environment by

novice and more advanced users.

System acceptability has been described as the

combination of practical and social acceptability

(Nielsen, 1993). Practical acceptability includes sev-

eral factors: support, reliability, compatibility, and

usefulness of both software and hardware. This can

be measured with usability methodologies; where the

term usability is understood as the effectiveness, effi-

ciency and satisfaction with which users achieve spe-

cific goals in particular environments:

Effectiveness assesses the accuracy and complete-

ness with which users can achieve specified goals

in particular environments;

Efficiency assesses the resources expended in rela-

tion to the accuracy and completeness of goals

achieved; and

Satisfaction is the comfort and acceptability of the

system to its users and other people affected by its

use.

Previous work on developing interfaces and in-

teraction techniques for 3D virtual environments has

been conducted by (Kjeldskov, 2001), (Bowman,

1998), (Poupyrev et al., 1997). Standard usability

engineering and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)

evaluation techniques have been adapted to 3D im-

mersive environments in order to be able to ad-

dress the usability problems introduced by these in-

terfaces. Usability work for 3D immersive environ-

ment has been previously researched by (Poupyrev

et al., 1997), (Sutcliffe and Kaur, 2000), (K.Deol

et al., 2000a), (K.Deol et al., 2000b) and (Bowman

et al., 2002). According to this work, the methods for

conducting usability studies can be classified accord-

ing to 3 factors:

• Involvement of representative users, which di-

vides methods between those that require the par-

ticipation of representative users (such as For-

mal Summative Evaluation and Post-hoc Ques-

tionnaire), and those methods that do not (meth-

ods not requiring users still require a usability ex-

pert, such as Heuristic Evaluation)

• The context of evaluation, which inherently im-

poses restrictions on the applicability and gener-

ality of results. Conclusions or results of eval-

uations conducted in a generic context, for ex-

ample Heuristic Evaluation, can typically be ap-

plied more broadly. Results of an application-

STUDYING USERS’ ACCEPTABILITY TOWARDS 3D IMMERSIVE ENVIRONMENTS - Virtual Tours: A Case

Study

479

specific evaluation method, such as Cognitive

Walkthrough, may be best-suited for applications

that are similar in nature.

• The types of results produced, which identi-

fies whether or not a given usability evaluation

method produces (primarily) qualitative or quan-

titative results.

Results from previous tests indicate that more nat-

ural hardware interfaces, such as wands, rather than

the traditional mouse, have more potential for interac-

tion within CAVE-like environments. However, there

are no guidelines for others types of set-ups. In addi-

tion, it has also highlighted the importance of incorpo-

rating features common to computers games into 3D

Immersive Virtual Environments. For example: using

artefacts as portals to previous times; using avatars

to deliver information; using “highlighted” objects as

hyperlinks; and using maps.

To add on the experience of this previous research,

our work involved studying individual user’s behav-

iors while using the Wolfenbuttel Virtual Tour pro-

ducing as a result both quantitative and qualitative

data. However, it should be noticed that according

to museums theory it will be impossible to use rep-

resentative users as every user will have an individual

context on which he/she experiences the environment.

The study was based on two combined methodolo-

gies: i) Formative Evaluation as well as ii) Post-hoc

Usability Questionnaires (Hix and Hartson, 1993).

Formative Evaluation is an observational, empirical

evaluation method that assesses user interaction by it-

eratively placing users in task-based scenarios in or-

der to assess the design’s ability to support user nav-

igation, acting (information seeking) and understand-

ing of subject material. This technique is application-

specific and produces qualitative results, such as crit-

ical incidents, user comments, and general observa-

tions. The results are expected to provide a basis for

exploring how visitors engage and interact with this

type of environment as it is critical to understand dif-

ferent personality-based interaction styles (i.e. strate-

gic vs. tactic). Post-hoc Usability Questionnaires pro-

duce quantitative results, which are useful to improve

applications’ designs further.

The testing usually lasted one to one and a half hours

and had the following format:

1. Introduction

2. Formative evaluation: performing five high level

tasks using the software and implementing a

‘Think aloud’ technique. Tasks ranged from open

goals such as exploration and discovery of ele-

ments in the environmentto more structured tasks.

The users were using a head tracker during this

part of the test which gaveus qualitative and quan-

titative information of the behaviours of the users

towards the environment (see figure 3).

3. Usability questionnaire: based on ISO 9241/10

standard usability questionnaire (Heinz, 1993).

Figure 3: Formative evaluation set-up.

In total, the research involve studying 12 case stud-

ies. This sample involved people with different ages,

levels of knowledge in ICT and attitudes towards mu-

seums and heritage sites. As previously mentioned,

the study acknowledged at all stages the sample was

limited, however the data produced by this 12 cases

produced a better picture of people’s attitudes and ac-

ceptability of the technology. The highest percentage

of the user sample ranged between 27 to 36 years old,

while 5 were male and 7 female. Average use of com-

puters ranged between 10 to 20 hours per week.

User’s knowledge of computing ranged from interme-

diate to advanced, but only 2 had advanced knowl-

edge in computer graphics. Three quarters of the sam-

ple play or have played computer games. This fact

definitely influenced the expectations and interaction

techniques with which users were familiar. The ma-

jority of users visited museums fairly often as half av-

eraged 2 to 5 visits per year and one quarter averaged

more than 6 visits per year. It should be noted that vis-

its to museums were done during traveling, as a high

percentage of the answers referred to museums which

are not in the local area or even in the UK.

3.1 Testing Users’ Data

Head tracker data was stored in a user’s log file con-

taining interception point and time stamps for syn-

chronization purposes. In addition, on screen video

interaction and user’s voice was captured. This pro-

vided a video and audio file in an AVI container;

which was used to evaluate the users opinions and

their thoughts from the speak aloud technique.

The difficulty of using the head tracking data within

GRAPP 2008 - International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

480

this environment is that each case study is completely

personal and making comparison between cases is

difficult. Users do not have a linear experience, but

a 3 dimensional exploratory experience. To overcome

this problem, we clustered the data of each user ac-

cording to the different tasks they performed and then

observed the similarities differences between each of

them. Observing the head data usually involved look-

ing into the actions of all users, specially the slower

and faster subjects to make a comparison. We also

listened to the comments of the users while they were

performing the tasks. This was not in any way a

straight forward task and the results where not always

easy to capture and represent.

Typically, a task was performed in an average of three

and a half minutes. Hence, the 5 tasks where typ-

ically completed in an average time of 18 minutes.

The users who had problems understanding the inter-

action techniques, performed very slowly, with a cou-

ple of them taking up to 9 minutes to complete the

first task. In addition, variations in time were related

to i) some users wanting to explore the environment

further, while others were just interested in accom-

plishing the tasks; as well as ii) users writing down

the answers on paper, whilst others would just speak

the answers out loud. These factors were taken into

account when assembling the conclusions of this ex-

ploratory study.

4 DISCUSSION OF RESULTS AND

OBSERVATIONS

The results are presented in terms of the main issues

that were identified by this research.

4.1 Acceptability

Opinions were divided when discussing the accept-

ability of such environments, especially for museums

and heritage sites. Although their conceptualization

potential was appreciated; visitors thought that the

Virtual place do not look realistic enough. One could

interpret this response suggesting that if ICT is to be

used then contextualisation is not enough, but also the

virtual authenticity of the object or place needs to be

considered.

Regarding the acceptability of the place, not all users

were convinced that the 3D virtual environment was

an acceptable representation of what the place would

have looked like in the seventeenth century, as only

half the users agreed with the statement. The users’

main concerns were:

• Only the exterior of buildings are shown, and not

the interiors. This is a technical limitation of the

application that was being used

• The apparent artificiality/sterility of the environ-

ment. Users suggested that this could be ad-

dressed though the inclusion of people and ani-

mals

These responses highlight the desire from users

to achieve certain degree of realism. There was

a struggle from users to request realism, while

not feeling comfortable with realistic interactions

techniques, as explained in the navigation section.

This dichotomy was highlighted several times during

the testing results.

There were also mixed feelings regarding the state-

ment that “the use of 3D virtual environments - like

this one - is a credible replacement for reading text

labels or audio guides in a museum”, with half of the

users agreeing but the other half disagreeing, although

not so strongly. This highlights the unfamiliarity

of users towards new ways of conceptualization; in

addition, to the acceptance of using not-so-authentic

virtual replicas of real historical objects.

Some of the comments from users were that it was

to easy to jump from one place to another without

really looking at the buildings and environment;

hence, people do not take in much of the information.

Another answer, very related to the museum setting

highlights the fact that in a place with lots of people

crowding around the machine, this type of envi-

ronment could be very impractical when compared

to audio guides unless they too were personalised,

which implies their availability on mobile equipment.

The fact that audio guides do not distract the visitor

from looking at the objects in the museum exhibition

is also important to consider. Visual guides might

be more applicable in cases where the modern day

environment appeared different from the historic

environment.

4.2 Enjoyment, Engagement and

Understanding of Historical

Material Presented

When discussing how people engaged with the

experience and found it fun, we find a strong link

with computer games. One user, who identified

the Avatar as representing herself, saw as a natural

interaction to go and ask other characters for the

information she was trying to find. She also tried to

walk into the building as a natural and enjoyable way

STUDYING USERS’ ACCEPTABILITY TOWARDS 3D IMMERSIVE ENVIRONMENTS - Virtual Tours: A Case

Study

481

to behave in such environment.

The application provided the user with information

in a variety of ways (i.e. web pages, question-answer

systems). Users tended to get confused regarding

the most suitable mechanisms to get an answer to

their questions. They felt very comfortable with

searching for information in a webpage, as they were

familiar with the interaction paradigm. Even when

information was in front of their eyes, using other

means, they seem not to find it very easily.

When evaluating differences in performance of tasks,

it was noted that slower users were using a more

exploratory approach. They took their time to see and

grasp the environment instead of just trying to extract

the information from it, while others focused only on

the movement and the text information presented by

the environment.

One of the tasks involved a ‘trick’ question to see how

much attention users were paying to the information

provided in text. After a few tests, it was obvious

that people also took different approaches to this:

those who read and focus mainly on facts (i.e. date

of birth, achievements of people, etc.) and those who

try to get the main idea from quickly gazing at the

text. This result might suggest that just as in labels,

users will not be very attentive to the text on an

ICT application, but other visual and audio elements

should be more suitable for the task.

In general, users felt positive with Virtual Tours

engaging visitors with museums and heritage sites.

This is the case as the visitors already have an interest

in the subject and want to know more. In addition,

it has some entertainment value for the user, which

can make visiting the museum more fun. This result

does contradict the disbelief of many to accept this

environments as a credible replacement for reading

text labels or audio guides in a museum. This might

indicate the conservative view of a museum from

the users although they do accept that this type of

environments could be more engaging for visitors.

4.3 Usefulness of Including Avatars in

the Environment

Users were very critical about including an Avatar

that they could not interact with in the Virtual Tour:

• Almost all women tended to think the Avatar was

a representation of themselves within the 3D envi-

ronment rather than as a virtual guide which was

providing them with help which it was intended to

be.

• Many women found the Avatar to be stressful be-

cause her gestures made her looked like if she was

bored or confused. One of the users thought she

was being pressured to choose something quickly.

• Other users disregarded her, as the Avatar was not

directly interacting with them. One user men-

tioned that he was not paying as much attention

to her as to the other parts.

Hence, if including an Avatar it is important to

make it interactive and be more involved in wel-

coming, giving instructions, pointing, or answering

questions. There was even a suggestion to write in her

shirt the word “GUIDE” to make this fact obvious.

These results highlight the importance of interactivity

over realism of the characters in a 3D immersive

environment. Again, the results highlight that users

thought the environment should look realistic, but

that finally it was the interactivity of its elements

what creates the engagement with it.

4.4 Learning Curve for using the

Environment by Novice and More

Advanced Users

As previously mentioned, most of the users already

had some knowledge on 3D systems. However, some

of them took long time to perform some of the tasks,

as they could not figure out the interaction technique

required. It should be highlighted that a minute for

learning a - new - interaction technique is far too long

for the ‘couple of minutes’, museums will expect a

user to spend with an application.

In addition, three quarters of users answered that they

were not able to use the fundamentals of the software

right from the beginning, without having to ask for

help. Only one user looked for help immediately,

which helped her scoring the shortest time of all. The

longest time on this task was achieved by a user who

tried different mechanisms for interaction until she

found the one suitable to perform the task.

4.5 Usability

General usability issues (many of them obvious but

missed previously by the design team) which were

highlighted include:

• When using large screens, such as the one used

for the test, text in labels has to be large enough to

read and the labels should not overlap each other.

• If there are triggers in a 3D environment, these

should only be displayed prominently when the

GRAPP 2008 - International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

482

user is able to click on them. There was an exam-

ple of a big bright yellow-red icon in the 3D en-

vironment, which highlighted the fact there was

more information available at the location, but

to the frustration of the users this could not be

clicked.

• The speed of animations must be carefully consid-

ered. For example the flying speed was a bit too

fast for users to appreciate the environment and

see the buildings. Hence, there is a need to give

some control to the users to stop, look around or

adjust the speed of their movement within the en-

vironment.

4.6 Interaction Mechanisms

Initially, the majority of the users had difficulty in

identifying the interaction mechanisms used by the

application. All users took time to get accustomed

to the navigation mechanisms. The lack of common

navigation techniques within this type of environment

could be a contributory factor to this problem. The

head tracking data, demonstrates that most users

focus on the area of the screen were most of the

movement is happening (as shown in figure-4). As

such, they attempt different actions mainly within

this space ignoring the other areas. Typically, users

attempted to interact by i) clicking on houses, doors

or on the virtual Avatar; ii) looking at the applications

menu or iii) moving the mouse or the key arrows

on the keyboard. None of them actively noticed the

fact that most of their interaction techniques have

been learned from playing computer games (in their

different genres).

The label based navigation mechanism (using labels

0

200

400

600

800

1000

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200

Previous 5 seconds of head tracking data for subject1.data at time=65

Figure 4: Head tracking data for user while performing a

task.

for jumping to locations in the 3D environment) was

not well received. Using labels with names of places

to navigate around the 3D space made it very contra-

dictory and confusing for users. Two thirds of users

failed to understand the geographical logic behind

the navigation. Most users would have preferred to

use an overview/map of the entire environment and a

list of all the places where it was possible to navigate

so they can orient themselves easily.

When users identified that they wished to move from

one location to another, the system responded by

flying to the destination, which is neither consistent

with users real-world experiences or those they gain

from the majority of virtual 3D worlds. One user

commented that it would have been more natural to

walk instead of flying to highlight this fact.

Users tried to navigate by typing requests into the

“Ask a question here” text field. Providing a non

restricted space to “Ask”, made them think they could

type anything including questions, requests, orders

to the system (i.e. “go to library”, “most important

places in town”, “map of town”, “how do I move”,

etc.) This highlights the need to inform the users of

the restrictions on the information the system can

provide at any time and providing help as soon as

entering the environment on what they can do or not

within the environment.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The Virtual Tour application presented in this paper

represents an example of the type of virtual environ-

ments that currently exist to contextualise the com-

munication of heritage. Although their popularity, it

has been acknowledge the difficulties on deciding the

most suitable interfaces for their use. As a result,

the paper has presented ongoing research to explore

user’s acceptability and behavior towards interfaces

and interaction techniques (in software and hardware)

for their use. The following observations were found

from our study:

• Although museum visitors still have a conserva-

tive view on the museum and its contextualization

devices; 3D immersive environments might be an

engagingway to provide additional information as

long as the representations contained are realistic

enough.

• To be acceptable, applications must consider their

context of use. In museums users may only able

to spend a few minutes using a display thus, wher-

ever possible the time required to learn an applica-

tion must be minimal as must be the time require

to explore the key information that it presents.

STUDYING USERS’ ACCEPTABILITY TOWARDS 3D IMMERSIVE ENVIRONMENTS - Virtual Tours: A Case

Study

483

• The purpose/function of Avatars must be made

clear to users. Avatars are only useful if they can

operate effectively within the constraints identi-

fied above.

• Avatarsmust meet users’ expectations particularly

in terms of the gestures and interactivity that they

support and the manner in which they engage with

users.

• Users should be able to control their speed of nav-

igation and route within the environment. If they

want to stop and explore allow them, while still

constraint the navigation so they do not get lost.

• Information should be presented in a variety of

ways (multimedia, text, etc), but have the same

interaction paradigm to be accessed. In this study,

users appeared to favor Hyperlinks.

• It is necessary to decide the target audience and

take this into account for present historical facts

in the most adequate interactive format. Language

of information should also be considered.

• Existing best practice interaction and visual de-

sign techniques should be utilized. For example:

designs must take into account the target display

size and resolution as well as the labels should

be meaningful and discernible. In addition, the

principles of affordance and constraints (Norman,

1988) should be exploited to reduce the cognitive

load placed on users.

Although this observations cannot be generalized and

are specific to the study we conducted, they can pro-

vide an insight into into current and potential mu-

seum’s users attitudes. There is further debate to be

had in the areas of realism of environment above in-

teractivity, and the role of computer games interfaces

and interaction techniques.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been conducted as part of the EPOCH

network of excellence (IST-2002-507382) within the

IST (Information Society Technologies) section of

the Sixth Framework Programme of the European

Commission. Our thanks go to the others involved

in the realisation of this work: Phil Flack and John

Glauert at the University of East Anglia as well as the

Interactive Technologies Research Group at Univer-

sity of Brighton. Thanks are also due to the Graphics

Research Groups at the Technical Universities of

Braunschweig and Graz for much the architectural

model.

REFERENCES

Bowman, D. (1998). Interaction techniques for immersive

virtual environments: Design, evaluation and appli-

cation. In Human-Computer Interaction Consortium

(HCIC) Conference.

Bowman, D., Gabbard, J., and Hix, D. (2002). A survey of

usability evaluation in virtual environments: Classifi-

cation and comparison of methods. Presence: Teleop-

erators and Virtual Environments, 11.

Falk, J. H. and Dierking, L. D. (1992). The museum experi-

ence. Whalesback Books, Washington, D.C.

Heinz, W. (1993). Isometricsl, questionnaire for the evalua-

tion of graphical user interfaces based on iso 9241/10.

Version: 2.01c March 1998.

Hix, D. and Hartson, H. R. (1993). Developing User Inter-

faces: Ensuring Usability through Product & Process.

John Wiley & Sons.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2000). Museums and the interpreta-

tion of visual culture. Routledge, London.

K.Deol, K., Steed, A., Hand, C., Istance, H., and Tromp,

J. (2000a). Usability evaluation for virtual environ-

ments: Methods, results and future directions (part 1).

Interfaces No 43, pages 4–8.

K.Deol, K., Steed, A., Hand, C., Istance, H., and Tromp,

J. (2000b). Usability evaluation for virtual environ-

ments: Methods, results and future directions (part 2).

Interfaces No 44, pages 4–7.

Kjeldskov, J. (2001). Interaction: Full and partial immersive

virtual reality displays. In Proceedings of IRIS24.

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability engineering. Academic Press

Limited.

Norman, D. A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things.

New York: Basic Books.

Poupyrev, I., Weghorst, S., Billinghurst, M., and Ichikawa,

T. (1997). A framework and testbed for studying ma-

nipulation techniques for immersive vr. In ACM Sym-

posium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology

(VRST).

Sutcliffe, A. and Kaur, K. D. (2000). Evaluating the us-

ability of virtual reality user interfaces. Behaviour &

Information Technology, 19:415–426.

Vergo, P. (2000). The reticent object. In The New Museol-

ogy. Reaktion Books Ltd.

Wright, P. (2000). The quality of vistor’s experiences in art

museums. In The New Museology. Reaktion Books

Ltd.

GRAPP 2008 - International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

484