WEBSITE SERVICE QUALITY IN IRELAND

A Consumer Perspective

Regina Connolly

Dublin City University, Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland

Keywords: eService Quality, small-to-medium enterprises, E-S-QUAL.

Abstract: Despite the fact that service quality is a critical determinant of website success, studies show that consumers

frequently view the service quality delivered through websites as unsatisfactory. This paper outlines a study

that is investigated the dimensions of website service excellence valued by Irish customers of a small to

medium enterprise specialising in gifts. The e-S-QUAL measurement instrument was applied to the

customers who purchase products online from this retailer, in order to determine their purchasing patterns

and the dimensions of e-service quality that they value. This study makes a major contribution to the

literature as it describes the application of the newly operationalised E-S-QUAL measurement instrument.

The results of this study will indicate the effectiveness of the instrument in determining gaps in e-service

quality. The findings will benefit both practitioners and researchers in developing an understanding of the

factors that contribute towards the creation and maintenance of consumer satisfaction in Irish online

transactions.

1 INTRODUCTION

In Ireland the need for online vendors to understand

the dimensions of e-service quality that customers

value has an added impetus as Irish consumers

continue to resist transacting via the Internet – using

it as an information rather than a transaction medium

and thus limiting its commercial potential. For

example, by the end of 2002, nearly half of the Irish

population had Internet access, but only 38% of Irish

Internet users had made an online purchase

(Amarach Consulting, 2002). Studies in the UK

have also found that the percentage of the Internet

population who shop online has not increased in line

with Internet penetration. Thus, while increases in

the sheer size of the Internet population mean that

more people have made an online purchase, the

proportion of Internet buyers is not increasing.

Therefore, in order that the commercial potential of

the Internet is to be realized - a potential that is

expanding dramatically as a result of advances in

consumer wireless technologies and their

transaction-facilitating capabilities – understanding

the dimensions of service quality that Irish online

consumers value is of critical importance.

1.1 Research Objectives

This research extends our understanding of service

quality within the setting of online retailing. The

study has two objectives. Firstly, it examines the

dimensions of website service quality that are valued

by customers of a small to medium online company

in Ireland. Secondly, by applying the newly

operationalised e-S-QUAL measurement instrument,

it explores the relevance of this instrument in the

evaluation of business to consumer website service

quality.

2 SERVICE QUALITY

Service quality in is one of the most researched

topics in the area of service marketing. Although

research into the dimensions of website service

quality that are valued by online consumers is in an

embryonic stage, it is an issue of considerable

importance. In part, this is due to the fact that as

competition for online consumers intensifies, service

quality has become a key differentiator for online

vendors and thus it has become increasingly

important to have an appropriate means by which to

measure it. This is particularly true in the business

378

Connolly R. (2008).

WEBSITE SERVICE QUALITY IN IRELAND - A Consumer Perspective.

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 378-386

DOI: 10.5220/0001519003780386

Copyright

c

SciTePress

to consumer electronic commerce marketplace

where web vendors compete for a limited number of

consumers and where consumer loyalty has become

a key indicator of success.

Service quality has been defined as the

difference between customers’ expectations for

service performance prior to the service encounter

and their perceptions of the service received

(Asubonteng et al., 1996). When performance does

not meet expectations, quality is judged as low and

when performance exceeds expectations, the

evaluation of quality increases. Thus, in any

evaluation of service quality, customers’

expectations are key to that evaluation. Moreover,

Asubonteng et al., (1996) suggest that as service

quality increases, satisfaction with the service and

intentions to reuse the service increase.

Meeting customer service requirements is both a

performance issue (whether the service satisfies the

customers requirements) and an issue of conformity

to measurable standards. For example, for Swartz

and Brown (1989) distinguish between the

consumer’s post-performance evaluation of ‘what’

the service delivers and the consumer’s evaluation of

the service during delivery. The former evaluation

has been termed ‘outcome quality’ (Parasuraman et

al., 1985), ‘technical quality’ (Gronröos (1983) and

‘physical quality’ (Lehtinen and Lehtinen, 1982).

The latter evaluation has been termed ‘process

quality’ by Parasuraman et al., (1985), ‘functional

quality’ by Gronröos (1983) and ‘interaction quality’

by Lehtinen and Lehtinen (1982).

The most frequently cited measure of service

quality is SERVQUAL, an instrument developed by

Parasuraman et al., (1985; 1988). It has been widely

cited in the literature and has been used to measure

service quality in a variety of settings e.g. health

care (Babakus and Mangold, 1992; Bebko and Garg,

1995, Bowers et al., 1994), large retail chains (Teas,

1993; Finn and Lamb 1991), fast food restaurants

(Cronin and Taylor 1992), a dental clinic, a tyre

store and a hospital (Carman 1990). Designed to

measure service quality from a customer

perspective, it consists of five basic dimensions that

represent the service attributes that consumers use to

evaluate service quality. The five dimensions are

tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and

empathy. In their model, Parasuraman et al., (1985;

1988) suggest that it is the gap between consumer

expectations with actual service performance that

informs service quality perceptions. To the degree

that service performance exceeds expectations, the

consumer’s perception of service quality increases.

To the degree that performance decreases relative to

expectations, the consumer’s perception of service

quality decreases. Thus, it is this performance-to-

expectations gap that forms the theoretical basis of

SERVQUAL. However, Parasuraman et al., also

note that the evaluation of service quality is not

based solely on the service outcome but also

involves evaluations of the process of service

delivery.

Despite its popularity, a number of issues related

to the use of SERVQUAL remain contentious, such

as the proposed causal link between service quality

and satisfaction (eg Woodside et al., 1989; Bitner

1990), and the question as to whether one scale can

be universally applicable in measuring service

quality regardless of the industry or environment

(Asubonteng et al., 1996; Cronin and Taylor 1992;

1994; Teas, 1993; Carman, 1990; Finn and Lamb,

1991). Moreover, although it remains the dominant

model for both researchers and managers, its

proposed universality and applicability is made even

more questionable by viewing the numerous

modifications that are evident in many studies that

purport to use this model (Paulin and Perrien, 1996).

2.1 e-Service Quality

Website service quality, frequently termed e-service

quality, has been defined as “consumers overall

evaluation and judgement of the excellence and

quality of e-service offerings in the virtual

marketplace (Santos, 2003) and “as the extent to

which a website facilitates efficient and effective

shopping, purchasing and delivery” (Zeithaml 2002).

E-service quality is constantly evolving due to the

pace of competition and the ease of duplicating

service features in the online world (Trabold et al.,

2006). Notwithstanding evidence of continuing

consumer dissatisfaction with service delivered

through the Internet (Gaudin 2003; Ahmad 2002)

studies of e-service quality remain limited and

frequently employ instruments that were developed

for use in a traditional environment such as the

SERVQUAL survey instrument. For example,

researchers (Van Iwaarden et al., 2004) have used

SERVQUAL to examine the quality factors

perceived as important in relation to the use of

websites, despite the fact that it was not designed to

measure perceived service quality in an online

environment and its applicability is therefore

unlikely to extend to that context. While it is true

WEBSITE SERVICE QUALITY IN IRELAND - A Consumer Perspective

379

that past conceptualisations can be useful platforms

for describing e-services (Van Riel, 2001), there is

an increasing awareness (Cai and Jun, 2003; Lie et

al., 2003) that the SERVQUAL instrument is limited

in terms of its ability to measure e-service quality

particularly as there are dimensions of service

quality unique to the electronic context. For

example, Cox and Dale (2001) argue that

dimensions of service quality specific to a traditional

environment such as competence, courtesy,

cleanliness, comfort, and friendliness, are not salient

in the electronic retail environment while such

dimensions as accessibility, communication,

credibility, and appearance, are of critical

importance in an on-line environment. Support for

inclusion of specific dimensions unique to the on-

line retail environment is also provided by Long and

McMellon (2004) who argue that factors such as

geographic distance and face-less ness of the

experience form part of the online service

experience and therefore should be part of any e-

service quality measurement instrument.

However, although several researchers have

proposed scales to evaluate websites, many of these

scales do not provide a comprehensive evaluation of

the service quality of the website. For example, the

focus of the WebQual scale (Loiacono et al., 2000)

is to provide website designers with information

regarding the website (e.g. informational fit to task)

rather than to provide specific service quality

measures from a customer perspective. Other scales

such as WebQual (Barnes and Vidgen, 2002)

provide a transaction-specific assessment rather than

a detailed service quality assessment of a website.

The SITEQUAL (Yoo and Donthu, 2001) scale

excludes dimensions central to the evaluation of

website service quality as does Szymanski and

Hise’s (2000) study, while researchers (Parasuraman

et al, 2005) have expressed caution regarding the

consistency and appropriateness of dimensions used

in the eTailQ scale proposed by Wolfinbarger and

Gilly (2003).

Recently however, many of these concerns have

been addressed by the original authors of the

SERVQUAL instrument through the development

and operationalisation of a multi-item scale for

examining website service quality (Parasuraman,

Zeithaml and Malhotra, 2005). This scale, termed

E-S-QUAL, is a four-dimensional, 22-item scale that

captures the critical dimensions of service quality

outlined in the extant literature. The dimensions are

efficiency, fulfilment, system availability, and

privacy. The scale has an accompanying subscale

called E-RecS-Qual which contains items focused

on handling service problems and is relevant to

customers who have had non-routine recovery

service encounters with the website. E-RecS-Qual

consists of a three-dimensional, 11 item scale.

These three dimensions comprise responsiveness,

compensation, and contact. Both scales, whose

specific purpose is the measurement of website

service quality, have been subjected to reliability

and validity tests and demonstrate good

psychometric properties.

As E-S-QUAL is a relatively new measure it has

therefore not been used extensively in online service

quality research. A recent study that has utilised the

measure (Kim et al., 2006) found that online

apparel retailers are failing on specific service

dimensions leading to dissatisfaction on the part of

their consumers. Such insights provide critical

insights and have the potential to assist apparel

retailers in improving their service and thus increase

their success in the commercial arena. In this study

the E-S-QUAL instrument will be applied to a

narrowly focused business context as has been done

by other researchers who have sought to identify the

key dimensions of service quality in contexts such as

online banks, or travel agencies (e.g. Jun and Cai,

2001; Van Riel et al, 2001).

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Having reviewed the relevant literature, the decision

was taken to use the E-S-Qual questionnaire

(Parasuraman et al., 2005). A well known, Dublin

based online retailer was chosen to host the

questionnaire. This portal assists 25 vendors to

maximise their online selling potential through

advertising special offers, co-ordinating deliveries

and taking advantage of Internet business models. It

was felt that as there was a mix of businesses selling

goods ranging from holidays to flowers, there would

be a good cross-section of customer types in terms

of ages, tastes, and spending power. Using the

portal as a host would have the added advantage of

targeting the research at the correct population; those

who regularly shop on line.

The authors met with the portal's Marketing

Manager and Web Content Manager to discuss the

possibility of the research being carried out there.

The discussions with the managers culminated in an

agreement that the portal would host the

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

380

questionnaire on each of their 25 partner stores. It

was also decided that three managers from each of

the stores (vendors) would complete an online

questionnaire similar to the customers so that

responses to the same statements could compared.

The authors agreed to provide a confidential report

for each individual vendor as well as a comparative

report for the online portal.

The final survey utilised, based on the

Parusaman et al., (2005) questionnaire, was divided

into two sections, 1 & 2 and set up in a web-based

format. Customers completed Sections 1 and 2 and

vendors completed Section 1 only. In Section 1 of

the survey a varying number of questions were

asked regarding several dimensions of online service

quality. The owners of the online gift website

requested that the questions relating to compensation

be omitted from the final questionnaire as they

viewed these questions as introducing a negative

view of interactions with the website.

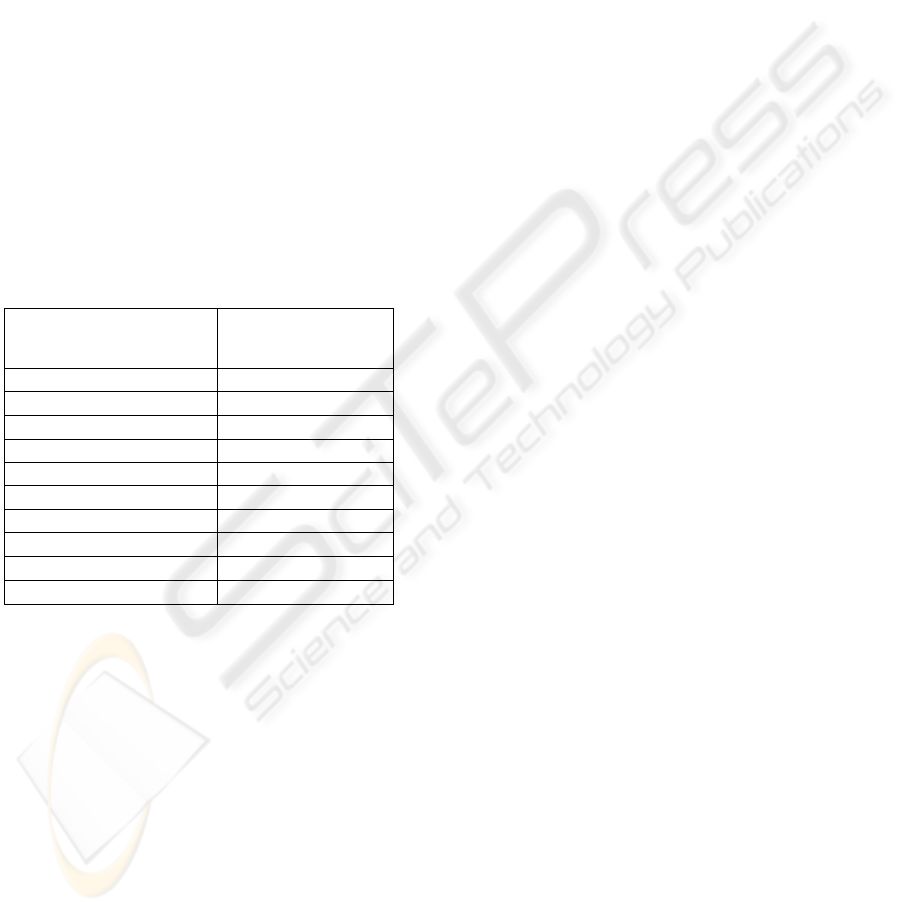

Table 1: eService Quality Dimensions.

eService Quality

Dimension

Number of

Questions

Efficiency 8

System availability 4

Fulfilment 7

Privacy 3

Responsiveness 5

Efficiency 8

Compensation* 3

Contact 3

Perceived value 4

Loyalty intentions 5

* Dimension omitted on request of online vendor

In addition, a statement on the influence of the

service quality dimension on the consumer’s trust

beliefs was also included. For example, in relation

to the dimension of website efficiency, customers

were asked to address the following: The ease of use

of a website increases my trust in the on-line vendor.

Section 2 of the survey collected demographic

information on the respondents.

In order to obtain participation in the study, the

Web Content Manager emailed customers to ask

them to take part in the web-based survey. The data

obtained from the questionnaire was converted into

Excel and analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences), a widely used programme

for statistical analysis.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Response Rates

A survey was undertaken for this research, and the

URL link to the survey web site was sent in the

participating company newsletter, via email to the

5,000 people who were registered customers. 84

respondents completed the questionnaire within 1

week of the initial notification. This represents

1.68% of the sample. A second notification was sent

by email 3 weeks later, which increased the number

of respondents to 119. This represents an increase of

43% to a total sample response rate of 2.38%. One

possible explanation for the low response rate is the

difficulty in checking the validity and continued

operation of the email addresses. This response rate

is despite the incentive of entry into a draw for a free

prize. The second mailing succeeded in increasing

the response rate from 1.68% to 2.38%. Within the

responses received 25% completed section 1 in full,

and all 119 completed section 2. This gives the

figure 0.6% as the percentage of the total sample that

returned a fully completed questionnaire for section

1, and 2.38% for section 2.

4.2 Reliability Analysis

The E-S-QUAL scale (Parasuraman, Zeithaml and

Berry, 2005) outlined four constructs for website

service quality and developed a scale by which these

constructs can be measured in relation to their

influence on perceived value and consumers’ loyalty

intentions. For the purpose of this study, it was

decided to also examine the relationship between

each of these four website service quality

dimensions and the online consumers trust response.

Table 2 shows the Cronbach’s alpha values for

each of the constructs. All of the constructs worked

well with this sample with the four constructs

‘Efficiency’, ‘Fulfilment’, ‘Responsiveness’ and the

‘Loyalty Intentions’ providing particularly strong

internal reliability measures.

WEBSITE SERVICE QUALITY IN IRELAND - A Consumer Perspective

381

Table 2: Reliability Analysis – Scale (Alpha).

Construct Number

of Items

Cronbach’s

Alpha

Efficiency 8 0.95

System

Availability

4 0.86

Fulfilment 7 0.94

Privacy 3 0.88

Responsiveness 5 0.95

Contact 4 0.85

Perceived Value 4 0.87

Loyalty Intentions 5 0.96

4.3 Correlation Results

Having secured reliability measures for the variables

the measure of association between pairs of

variables was now examined using correlation

techniques. Correlation is a statistical technique that

provides a measure of the association between two

variables i.e. how strongly the variables are related,

or change, with each other. In order to test the data

a simple average for each of the related questions

was calculated for each construct and the

relationship between the variables then considered.

The correlation coefficient results are displayed in

appendix 1.

The website service quality constructs showing

the strongest inter-relationships are system

availability with privacy (0.84), and efficiency with

system availability (0.80). The weakest inter-

relationships are those of fulfillment with contact

(0.39) and privacy with contact (0.53). The

relationships between the website service quality

constructs and the dependent variables were then

examined. In relation to the dependent variable

‘perceived value’, the strongest result is provided by

the responsiveness construct (0.87), followed by the

system availability construct (0.81). The weakest

relationship is that between contact and perceived

value (at 0.72).

In relation to the dependent variable ‘loyalty

intentions’, the results again show a positive

relationship between the dependent and independent

variables. However, the website service quality

dimensions show a slightly weaker relationship with

customer loyalty than with perceived value.

Efficiency has the strongest influence on customer

loyalty at 0.76 and this is followed by system

availability at 0.68. This indicates that website

attributes exert a strong influence on the loyalty

intentions of online customers. Interestingly,

fulfillment and privacy were the website service

quality variables with the weakest relationships with

loyalty intentions at 0.62 each.

Finally, the results indicate a positive

relationship between each of the dependent

variables. The strongest level of association was

that between trust and perceived value (0.76), with

the next strongest being that between perceived

value and loyalty intentions (0.72) and the weakest

of these relationships being that between trust and

loyalty intentions (0.60).

4.4 Regression Analysis

Multiple regression techniques were used in this

study to establish whether the set of independent

variables could explain a proportion of the variation

in the dependent variables at a significant level, and

to establish the relative predictive importance of the

independent variables. The independent variables

were: Efficiency, System Availability, Fulfilment,

Privacy, Responsiveness and Contact. The

dependent variables are Perceived Value and

Loyalty Intentions. The results, outlined in tables 3

and 4 show that these independent website service

quality variables explain 87% of the variation in

perceived value and 69% of the variation in loyalty

intentions respectively.

Table 3: Model Summary: Perceived Value.

R R Square

Adjusted

R Square

Std.

Error

of Estimate

.936

(a)

.876 .844 .28194

Independent variables: Efficiency, System Availability,

Fulfillment, Privacy, Responsiveness, Contact. Dependent

variable: Perceived Value

Table 4: Model Summary: Loyalty Intentions.

R R Square

Adjusted R

Square

Std. Error of

the Estimate

.829(a) .687 .605 .51010

Independent variables: Efficiency, System Availability,

Fulfillment, Privacy, Responsiveness, Contact.

Dependent variable: Loyalty Intentions

The F-statistics for each of the relationships

reported above indicate that with 99.9% confidence,

we can assert that there is a systematic relationship

between the dependent variables and the set of

independent variables. Thus, at least one of the

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

382

independent variables is explaining changes in the

dependent variable.

Predictive Importance of Independent Variables.

Perceived Value: The coefficient results indicate that

two of the independent variables – system

availability (coefficient beta weight 0.390) and

responsiveness (coefficient beta weight 0.371) -

exert the strongest effect on the dependent variable

perceived value. Fulfilment and contact are

significant independent variables – but to a lesser

degree. Each of these variables is positively related

to the dependent variable.

Loyalty Intentions: The coefficient results

indicate that two of the independent variables -

fulfilment (coefficient beta weight 0.355) and

contact (coefficient beta weight 0.329) - exert the

strongest effect on the dependent variable Loyalty

Intentions. However, none of the independent

variables are statistically significant. This result

contradicts the results of the F-test that indicated

with 99.9% confidence that there was a systematic

relationship in this case. This contradiction is a

typical outcome where independent variables are

highly correlated with one another – where

multicollinearity is present. The coefficient results

for both dependent variables are shown in appendix

1.

5 DISCUSSION

The study findings provide evidence of a strong

relationship between the system availability and

privacy dimensions of website service quality. This

indicates that consumers’ evaluation of a website as

reliable (in terms of availability for business)

appears to result in a parallel evaluation of the

vendor as likely to take adequate measures to protect

their personal information. The findings also

confirm a strong inter-relationship between system

availability and efficiency, confirming the close

association between these dimensions of website

service quality in the mind of the consumer.

An interesting distinction emerged in terms of

the difference between contact and responsiveness.

For example, the results show that consumers’

perception of value is positively influenced by

vendor responsiveness but negatively influenced by

contact. This indicates that while consumers

perceive aspects of responsiveness such as the

ability to take care of consumer problems, to handle

product returns well, and to tell the consumer what

to do if a transaction is not processed as adding

value to their service interaction with the vendor, all

contact must be initiated by the consumer as non-

solicited contact (e.g. as with event notification

emails) is perceived as an infringement of privacy.

The service quality variable with the strongest

ability to influence consumers’ perception of value

is efficiency, followed by system availability, again

confirming the inter-relationship between these two

variables. Similarly, in relation to consumers’

loyalty intentions, the dimensions of website service

quality that provide the strongest explanatory power

are efficiency and system availability respectively.

These results indicate that technical website

attributes such as ease of use and reliability have

strong potential to influence perceived value and

customer loyalty and outweigh consumers’

fulfillment and privacy concerns. Vendors seeking

to increase consumer’s perception of value and

intention to re-purchase from the website should

therefore focus on the ease of use of the website

customer interface and the reliability of their

websites.

While previous research has argued that privacy

of websites may not be critical for more frequent

users (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003), the results of

this study indicate otherwise. For example, the

majority of respondents in this study were

reasonably frequent purchasers from this gift

website (29% purchased on a monthly basis and

33% purchased every 2-3 months) spending an

average of €50-€149 per transaction. While

experience may mitigate concerns about website

security, it clearly does not mitigate the influence of

privacy concerns on the online consumers’ trust

response.

Finally, the use of the E-S-QUAL measurement

instrument in an Irish context provided interesting

insights into the critical facets of website service

quality valued by Irish consumers. The authors of

the E-S-QUAL instrument had previously applied it

in the United States. Based on their results they

concluded that the most critical and equally

important E-S-QUAL dimensions were the

efficiency and fulfillment dimensions and that

customers’ assessment of a website on these two

dimensions would have the strongest influence on

perceived value and loyalty intentions. In this study

the full measurement instrument (comprising E-S-

WEBSITE SERVICE QUALITY IN IRELAND - A Consumer Perspective

383

QUAL and E-RecS-QUAL) was applied and the

results obtained differ considerably from those of the

instrument authors. For example, system

availability and responsiveness respectively were the

dimensions of website service quality shown to exert

the strongest effect on perceived value, while in

relation to loyalty intentions, the variables fulfilment

and contact exert the strongest effect.on the

dependent variable. System availability is a

significant independent variable – but to a lesser

degree. However, due to the limitations relating to

sample size further research is necessary to establish

whether or not the E-S-QUAL model is culture

independent. At present, all that can be concluded is

that this study has provided results that indicate that

online consumers in Ireland differ in terms of the

facets of website service quality that most influence

their perceptions of value and their loyalty

intentions.

6 CONCLUSIONS

One of the limitations of this study relates to the

sample size, a fact that was beyond the control of the

authors. Secondly, the company used in the study

was an online gift store. The fact that those

purchasing from this website are purchasing

products that they will not be consuming themselves

may lead to a different emphasis on certain facets of

service quality. In order to ascertain whether this

could indeed be the case, it is necessary to conduct

further website service quality studies of websites

where the consumer is purchasing the product for

their own use. Thirdly, the online vendor in this

study requested that the items on compensation

should not be included in the questionnaire, as the

company did not provide product compensation

assurances. This resulted in one of the E-RecS-Qual

sub dimensions being omitted from the study.

While the E-RecS-QUAL section of the study is

secondary to the E-S-QUAL section, which was

represented in full, it is nevertheless a point that

should be noted as the other two sub dimensions of

E-RecS-QUAL were included in this study. Finally,

this study extended the E-S-QUAL model by

introducing a number of trust items relating to each

of the service quality dimensions. However, it is not

claimed that these items provide an extensive

representation of consumer trust in the online vendor

and further research to specifically measure the

influence of website service quality on online

consumers’ trust responses would be valuable.

The study also contributes to the small but

growing body of work that exists on website service

quality and provides insight into the use of the E-S-

QUAL instrument in an Irish context. The insights

provided by this study will also be of benefit to

practitioners in their efforts to compete for and

retain customers in the competitive electronic

commerce marketplace.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, S. (2002) “Service Failures and Customer

Defection: A Closer Look at On-line Shopping

Experiences.” Managing Service Quality, 12 (1) 19-

29.

Amarach Consulting TrendWatch Technology Report,

Quarter 2, 2002. Available at

http://www.amarach.com/news/press.htm

Asubonteng, P., McCleary, K.J., Swan, J. (1996),

"Servqual revisited: a critical review of service

quality", Journal of Services Marketing, 10 (6) 62-81.

Babakus, E., Boller, G.W. (1992), "An empirical

assessment of the SERVQUAL scale", Journal of

Business Research, 24 (3), 253-68.

Babakus, E., Mangold, G.W. (1989), "Adapting the

SERVQUAL scale to hospital services: an empirical

investigation", Hospital Services Research, 26 (6)

767-86.

Barnes, S. J. and Vidgen, R.T. (2002) “An Integrative

Approach to the Assessment of E-Commerce Quality”

Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 3 (3) 114 –

27.

Bebko, C.P., Garg, R.K. (1995), "Perceptions of

responsiveness in service delivery", Journal of

Hospital Marketing, 9 (2) 35-45.

Bitner, M.J. (1990), "Evaluating service encounters: the

effects of physical surroundings and employee

responses", Journal of Marketing, 54 (2), 69-82.

Bowers, M.R., Swan, J.E., Koehler, W.F. (1994), "What

attributes determine quality and satisfaction with

health care delivery?", Health Care Management

Review, 19 (4), 49-55

Cai, S. and Jun. M. (2003) “Internet Users Perceptions of

On-line Service Quality: A Comparison of On-line

Buyers and Information Searchers”, Managing Service

Quality, Vol 13, No 6, pp 504 – 519.

Carman, J.M. (1990), "Consumer perceptions of service

quality: an assessment of the SERVQUAL

dimensions", Journal of Retailing, 66 (1), 33-55.

Cox, J., and Dale, B.G. (2001) “Service Quality and e-

Commerce: An Exploratory Analysis”, Managing

Service Quality, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp 121 –131.

Cronin, J.J., Taylor, S.A. (1994), "SERVPERF versus

SERVQUAL: reconciling performance-based and

perception-minus-expectations measurement of

service quality", Journal of Marketing, 58 (1), 125-31.

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

384

Cronin, J., Taylor, S.A. (1992), "Measuring service

quality: a reexamination and extension", Journal of

Marketing, 56 (July), 55-68.

Doney, P.M., Cannon, J.P., and Mullen, M.R. (1998),

‘Understanding the Influence of National Culture on

the Development of Trust’, Academy of Management

Review, Vol. 23 (3), pp.601-620.

Finn, D., Lamb, C. (1991), "An evaluation of the

SERVQUAL scale in a retailing setting", Advances in

Consumer Research, 18, 483-90.

Fukuyama, F. (1995), Trust: The Social Virtues and the

Creation of Prosperity. New York, Free Press.

Gaudin, S. (2003) “ Companies Failing at On-line

Customer Service” Retrieved from

http://itmanagement.earthweb.com/erp/article.php/158817

1

Gefen, D. and Heart, T. (2006) “On the Need to Include

National Culture as a Central Issue in E-Commerce

Trust”, Journal of Global Information Management,

Vol. 14, Issue 4, pp 1-30.

Grönroos, C (1983), Strategic Management and Marketing

in the Service Sector, Marketing Science Institute,

Cambridge, MA .

Hofstede, G. H. (1984). Culture’s Consequences:

International Differences in Work-Related Values.

Beverly Hills, CA.: Sage Publications.

Lehtinen, J.R and Lehtinen, U. (1982), "Service quality: a

study of quality dimensions", Unpublished working

paper, Service Management Institute, Helsinki .

Loiacono, E, Watson, R.T., Goodhue, D. (2000)

“WebQual: A Web Site Quality Instrument,” Working

paper, Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

Long, M. and McMellon, C. (2004) “Exploring the

determinants of retail service quality on the Internet”,

Journal of Services Marketing, 18(1), pp.78–90.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., and Malhotra, A.

(2005) “E-S-Qual: A Multiple Item Scale for

Measuring Electronic Service Quality”, Journal of

Service Research 7, (3), 213 – 233.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L. (1988),

"SERVQUAL: a multiple item scale for measuring

customer perceptions of service quality", Journal of

Retailing, 64 (1), 12-40.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L. "1985", in A

conceptual model of service quality and its

implications for future research (Eds), Journal of

Marketing, 49 (Fall), 41-50.

Paulin, M and Perrien, J. (1996) Measurement of Service

Quality: The Effect of Contextuality, in Kunst and

Lemminck (eds.) Managing Service Quality, London,

Chapman.

Santos, J. (2003), "E-service quality: a model of virtual

service quality dimensions", Managing Service

Quality, Vol. 13 No.3, pp.233-46

Shaffer, Teri Root and Bradley S. O’Hara (1995), “The

Effects of Country of Origin on Trust and Ethical

Perceptions”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol.

15,

(April), pp. 162-179.

Swartz, T.A., Brown, S.W. (1989), "Consumer and

provider expectations and experience in evaluating

professional service quality", Journal of the Academy

of Marketing Science, 17, 189-95.

Szymanski, D. M and Hise, R. T. (2000) “e-Satisfaction:

An Initial Examination,” Journal of Retailing, 76 (3),

309 – 22.

Teas, K.R. (1993), "Consumer expectations and the

measurement of perceived service quality", Journal of

Professional Services Marketing, 8 (2), 33-53.

Trabold, L. M., Heim, G., Field, J, (2006) “Comparing e-

service performance across industry sectors: Drivers of

overall satisfaction in online retailing” International

Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol 34,

No 4/5, pp. 240 – 257.

Van Iwaarden, J., Van der Wiele, T., Ball, L., Millen, R.

(2004) “Perceptions about the Quality of Websites: A

survey amongst students and Northeastern University

and Erasmus University”, Information and

Management, 41 (8), 947 – 959.

Van Riel, A., Liljander V., and Jurriëns P. (2001),

Exploring Consumer Evaluations of E-Services: A

Portal Site, International Journal of Service Industry

Management, Vol. 12, No 4, pp. 359-377.

Wolfinbarger, M. and Gilly, M.C. (2003) “eTailQ:

Dimensionalizing, Measuring, and Predicting etail

Quality,” Journal of Retailing, 79 (3) 183 – 98.

Woodside, A.G., Frey, L.L., Daly, R.T. (1989), "Linking

service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioral

intention", Journal of Health Care Marketing, 9 (4), 5-

17.

Yoo, B. and Donthu, N. (2001) “Developing a Scale to

Measure the Perceived Quality of an Internet

Shopping Site (Sitequal) Quarterly Journal of

Electronic Commerce, 2 (1) 31 – 46.

Zeithaml, V. (2002), "Service quality in e-channels",

Managing Service Quality, Vol. 12 No.3, pp.135-8.

Zucker, L.G. (1986), ‘Production of Trust: Institutional

Sources of Economic Structure, 1840 – 1920’, In

Staw, B.M., and Cummings, L.L. (eds.), Research in

Organizational Behavior, Vol. 8, pp. 53-111. JAI

Press, Greenwich, CT.

WEBSITE SERVICE QUALITY IN IRELAND - A Consumer Perspective

385

APPENDIX

Correlation Coefficient Results

Correlation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Efficiency (1) 1.

00

0.80 0.56 0.67 0.82 0.71 0.79 0.76

System Availability (2) 1.00 0.60 0.84 0.73 0.53 0.81 0.68

Fulfillment (3) 1.00 0.78 0.63 0.39 0.73 0.62

Privacy (4) 1.00 0.75 0.53 0.80 0.62

Responsive (5) 1.00 0.71 0.87 0.72

Contact (6) 1.00 0.72 0.69

Perceived Value (7) 1.00 0.72

Loyalty Intentions (8) 1.00

Regression Coefficient Results: Perceived Value

Unstandardized

Coefficients

Standardized

Coefficients t Sig.

B

Std.

Error Beta

1 (Constant)

-.790 .441 -1.794 .086

Efficiency

-.099 .177 -.093 -.560 .581

System Av

.425 .192 .390 2.212 .037

Fulfillment

.335 .140 .295 2.389 .025

Privacy

-.100 .183 -.102 -.548 .589

Responsiveness

.356 .147 .371 2.423 .024

Contact

.247 .112 .249 2.197 .038

Regression Coefficient Results: Loyalty Intentions

Model

Unstandardized

Coefficients

Standardized

Coefficients t Sig.

B

Std.

Error

Beta

1 (Constant)

-.863 .797 -1.083 .290

Efficiency

.284 .320 .235 .886 .385

System Av

.326 .347 .263 .938 .358

Fulfillment

.460 .254 .355 1.810 .083

Privacy

-.281 .330 -.253 -.852 .403

Responsiveness

.068 .266 .062 .255 .801

Contact

.371 .203 .329 1.826 .081

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

386