FORENSIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PHISHING

Petty Theft or Organized Crime?

Stephen McCombie, Paul Watters, Alex Ng and Brett Watson

Cybercrime Research Lab, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia

Keywords: Phishing, Attack Grouping, Organized Crime, Computer Crime, eCrime Forensics.

Abstract: Phishing, as a means of pilfering private consumer information by deception, has become a major security

concern for financial institutions and their customers. Gartner estimated losses in 2006 to phishing in the US

were approximately USD$2.8 Billion. Little has been published on the forensic characteristics exhibited in

phishing e-mail. We hypothesize that shared features of phishing e-mails can be used as the basis for

grouping perpetrators using at least a common modus operandi, and at most, a level of criminal organization

– i.e., we suggest that phishing activities are carried out by a small number of highly specialized phishing

gangs, rather than a large number of random and unrelated individuals using similar techniques. Analysis of

repeated phishing e-mails samples at a major Australian financial institution – using a criminal intelligence

methodology - revealed that 6 groups, from a sample of 500,000 spam e-mails, could be uniquely classified

by constructing simple decision rules based on observed feature sets, and that 3 groups were responsible for

86% of all incidents. These results suggest that – at least for the institution concerned – there appears to be a

level of criminal organization in phishing attacks.

1 INTRODUCTION

The hacking scene has, with the rise of phishing,

been transformed in recent years from a culture

based largely on youthful exploration, to one

focused on criminal profit (Stamp et al,2007).

APACS, the UK payments association, reported UK

online banking fraud was GBP£33.5 million in 2006

(APACS, 2007). In January 2006, the Bulgarian

National Services to Combat Organized Crime

(NSCOC) agency arrested an organized ring of eight

individuals who allegedly operated an international

“phishing” operation (Technology News Daily,

2006). Considerable anecdotal evidence exists to

suggest that other transnational organized crime

groups are involved in phishing activities (Naraine,

2006).

To date, there has been little research into the

individuals and groups behind phishing, how they

are organized, and what methods they use. To

effectively combat organized (rather than petty)

criminals, a greater understanding of the means,

motives and opportunities is required. Of course,

phishing may not be a major concern for organized

crime, and even if there were specific criminal

“signatures” that indicated a level of organization,

these may simply reflect a common modus operandi,

as much as the sharing of intelligence and

coordination of activities.

The goal of this paper is to present a first

attempt at a new criminal intelligence methodology

that aims to answer the question of how organized

phishing groups are, in terms of modus operandi and

coordination of attacks. To this end, we have

investigated phishing attacks at a major Australian

financial institution for two time periods (July and

October 2006). The aim was not do a “breadth first”

search of all targets of phishing, but to examine the

characteristics of attacks against a specific target.

The results presented below present a level of

support for our hypothesis that there is a high level

of organization in phishing attacks – at least for the

institution concerned – but further will be needed to

see if the results are generalizable to financial

institutions as a group, and to other organizations at

large.

The first data set used in this study comprised a

subset of identified phishing e-mails from a monthly

“spam collection” in excess of 500,000 messages in

July 2006. 71 unique phishing incidents were then

149

McCombie S., Watters P., Ng A. and Watson B. (2008).

FORENSIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PHISHING - Petty Theft or Organized Crime?.

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, pages 149-157

DOI: 10.5220/0001524401490157

Copyright

c

SciTePress

identified. By examining these incidents using the

method described below, we attempted to determine

the level of organization for each attack, by

examining their timing, and the relationship between

each other. The method was then repeated for the

October 2006 sample.

2 RELATED WORK

The majority of existing research phishing has

focused on areas such as studying user response to

phishing e-mails (Dhamija et al, 2006)((Jagatic et al

2005), tools to model phishing attacks (Jakobsson

2005), and e-mail content filtering defense

mechanisms against phishing activities such as the

Barracuda Spam Firewall, Microsoft Phishing Filter

and Symantec Brightmail Anti-Spam software. Abad

(2005) studied the economy of phishing networks by

analyzing e-mails and instant messages collected

from key phishing-related chat rooms. However, his

work did not look into the forensic information of

those phishing e-mails.

In regard to the research in analyzing the

content of phishing e-mails for detection and

classification purposes, both Chandrasekaran et al.

(2005) and Fette et al. (2000) have focused on

determining whether an e-mail is a phishing attempt

or not. Ramzan and Wừest (2007) have focused on

the trends seen in phishing attacks throughout 2006.

The closest work to this research is reported by

James (2005) that 48 distinct phishing groups were

identified by analyzing the nature of the phishing e-

mails and the phishing websites.

The analysis framework, as it stands, relies

primarily on characterizing and determining the

frequency of certain features in the phishing e-mails

using a type of authorship analysis, to determine

forensic signatures.

3 METHODS

Casual observations to date have been that incidents

seem to be able to be grouped due to a large number

of common characteristics. One well publicized

group known as the “RockPhish” (McMillan, 2005)

is well known by responders because of their

distinctive style of attack. Thus, to answer our

research question regarding the level of organization

of phishing attacks, we have sought to make use of

these distinctive features in developing a criminal

intelligence methodology for phishing, based on

authorship analysis.

Research in the mining of e-mail content for

authorship analysis has a carried a long history since

the advent of e-mail in the 1990s (de Vel, 2005).

The application of authorship analysis is usually

focused on collecting authorship characteristics to be

used in the context of plagiarism detection.

However, authorship analysis can also be applied to

identify a set of characteristics that remain relatively

constant and unique to a particular author – in this

case, the hypothesized phishing gangs.

To minimize systematic error and bias in

making general observations across a range of

different target sites, we focused on understanding

the phishing attacks occurring at a major Australian

financial institution. Two sets of e-mail spam data,

of which phishing forms a subset, were analyzed

(from July and October 2006).

We initially applied the authorship analysis to

the July data set, with the intention of testing the

reliability from this sample to a later October

sample. We were interested here in both the

variation in techniques used as a function of time,

and whether discrete groups could still be identified.

In developing the criminal intelligence

methodology, we primarily followed James’ (2005)

work by investigating the following key items for

identification:

• Bulk-mailing tool identification and

features.

• Mailing habits, including, but not limited

to, their specific patterns and schedules

• Types of systems used for sending the spam

(e-mail origination host)

• Types of systems used for hosting the

phishing server

• Layout of the hostile phishing server,

including the use of HTML, JavaScript,

PHP, and other scripts

• Naming convention of the URL used for

the phishing site

• IP address of the phishing site

• Assignment of phishing e-mail account

names

• Choice of words in the subject line

• The time-zone of the originating e-mail

Building on this approach for each incident,

where the data was available, the following features

were also examined:

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

150

• The e-mail source including text used,

metadata and header information

• The web pages and web hosts used

including directory structure and files

• Any other characteristics which may have

identified a link between separate incidents

Based on feature similarity, the incidents were

assigned a group number for each identified

characteristic for the July dataset. Consideration was

given to other causes of similarity, such as

coincidental use of shared “phishing kits” (which

might be the phishing equivalent of a rootkit), and

spam-generating tools that may have produced

similar footprints. Sets of rules based on these

characteristics were used to produce a set of Perl

scripts to analyze the October dataset.

The data examined for each incident included

the full e-mail header and body. The content and

structure of the phishing site, WHOIS information

for each IP and domain used, details of web server

software, operating system and port banners for

other services running, were then obtained.

Gathering together all of the potentially relevant

information – from common DNS registrants to

spelling mistakes – allowed us to build up a highly

detailed case file for each incident, which in turn

provided a rich data source for unique classification

of each incident by a hypothesized criminal group.

4 RESULTS

The results below are presented with an ethical

preface, in that some details of the investigative

methodology have been simplified or omitted for the

purpose of not revealing the exact modus operandi

of the perpetrators. The goal here is to prevent

alerting of the groups concerned (who may then

change their techniques), and also to prevent other

groups from adopting these techniques. Thus, in

some cases, representative results that could be used

to group the incidents have been presented, rather

than compromising ongoing criminal investigations.

4.1 Grouping of Phishing Gangs

A number of attributes including structural features,

patterns of vocabulary usage, stylistic and sub-

stylistic features are common attributes being used

in authorship analysis, were used to define groups in

this study (de Vel et all, 2000). In all instances, at

least three otherwise unrelated elements being used

in common across incidents were used to allocate an

incident to a group.

The grouping exercise identified six groups

comprising 69 of the 71 incidents. The 6 groups

were designated Group 1 to 6, and for the purposes

of illustration, some general descriptions of the

criteria that were used to select the groups are given

below:

• The presence of distinctive phrases

(especially spelling errors) in the message

text.

• The presence of HTML hyperlinks in the

message text, with a URL matching a

specific pattern.

• The DCC checksums of the message text

(indicative of identical text).

• The presence of certain exact strings in

header fields (such as "From", "X-Mailer",

and "X-Priority").

• The matching of a specific pattern in header

field values (such as the subject, message-

ID, and various e-mail address fields).

• The structure of given header fields, where

more than one element was available for

use (such as "Received" and "To").

• The overall MIME structure of the message

(such as "text/plain" and then "text/html"

enclosed in "multipart/related").

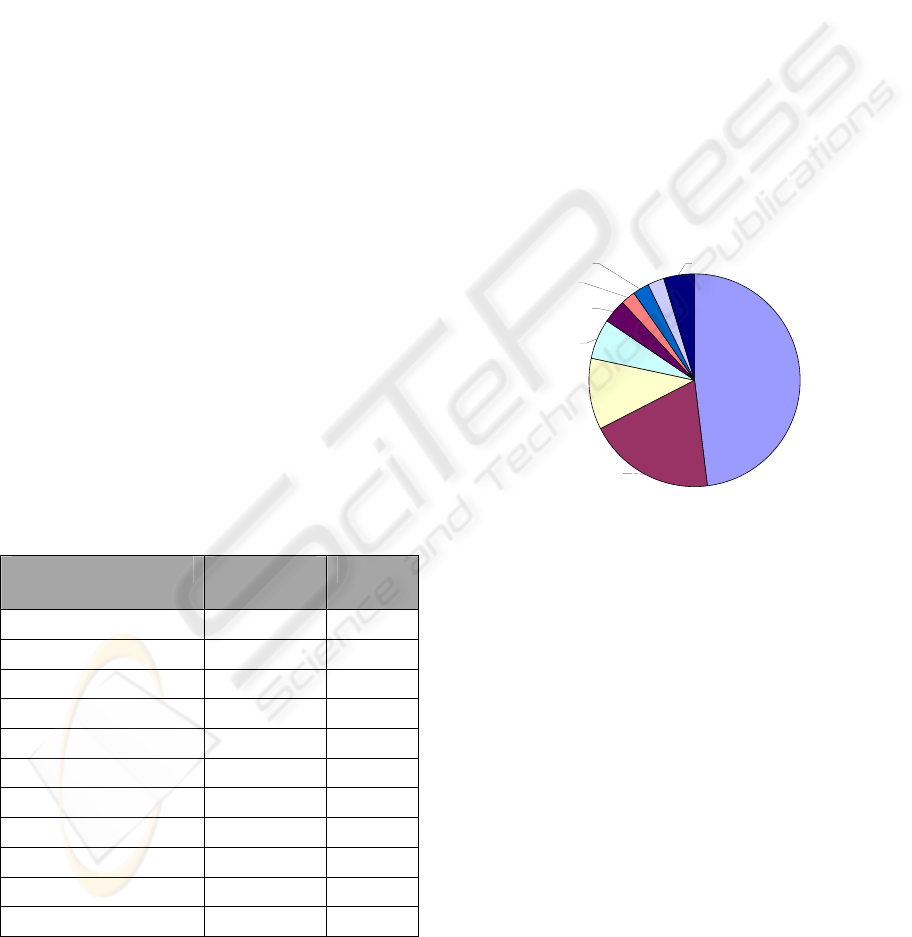

Figure 1 shows the relative composition of each

group, and indicates that two incident were unable to

be grouped using our methodology. Significantly, 61

of the 71 incidents were attributed to just three

groups 1, 3 and 4. Those three groups in percentage

terms accounted for an astonishing 86% of all

incidents.

Figure 1: Distribution of Phishing Incidents among

Groups in July 2006.

Group 6,

2, 3%

Group 5,

3, 4%

Group 1,

30, 43%

Group 2,

3, 4%

Group 3,

13, 18%

Group 4,

18, 25%

Unclassified,

2, 3%

FORENSIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PHISHING - Petty Theft or Organized Crime?

151

4.2 Values that Enabled Grouping

Sub-groups within the spam corpus were identified

by selecting several distinctive features of the kind

described in Section 3. In this section we describe

some of those criteria in more detail, and our

quantitative findings.

4.2.1 Structure of Phishing Site

The URL structure was one of the elements used to

group the incidents. Initial grouping by e-mail

header data was often confirmed in phishing site

structure. It was initially thought that web elements

of each attack may have been more useful in

grouping. However, on reflection, many of the non-

content web site elements were dependant not on the

phishing groups themselves, but the victims whose

sites are compromised to host the phishing sites. We

considered the possibility that phishing kits which

consisted primarily of web content may be

responsible for some similarities in URL structure

and web content, but we would not expect to see

similarities in e-mail values as well, as a result of

using these kits. Based on the information available

from the July corpus, we investigated the contents of

86 phishing sites such as: details of the phishing

site’s URL, host IP address, domain registrant,

domain registrar, country, NINS, CIDR, operating

system, Web server type, the Web content and

Charset used, and so on.

Table 1: Commonly used words in the URLs of July 2006

phishing incidents.

Commonly Used Words Occurrence

(total 86 URIs)

Percentage

Index 58 67%

victimbank 48 56%

victimbankib 41 48%

victimbankal 37 43%

victimbankib/index.htm* 36 42%

Php 24 28%

Secure 18 21%

Online 15 17%

Cgi 13 15%

agreement 12 14%

Login 9 10%

Table 1 summarizes some of the commonly

used words found in the URLs of phishing sites. In

this example, the legitimate URL of the target’s

website was victimbank.com. As expected, the word

“victimbank” (56%) had a high occurrence.

However, variations such as “victimbankib” (48%)

and “victimbankib/index.htm” (42%) were also

observed. The use of this particular pattern

“victimbankib” suggests a common nomenclature

originating from a specific group of phishers. To

substantiate this claim, we examined other details

such as IP address, OS, Web server type, etc.

collocated with the “victimbankib” pattern, and

found the following:

• A particular range of class C IP subnet

addresses range were frequently being used

(28%). The result from a whois-search

shows the IP range was managed by a

particular Regional Internet Registry (RIR)

in Europe.

• There are also many IP addresses used were

in the class A subnet range (34%).

Russia

4%

Germany

2%

Korea

6%

China

2%

Canada

2%

others

5%

USA

49%

GreatBritain

19%

MultipleSites

11%

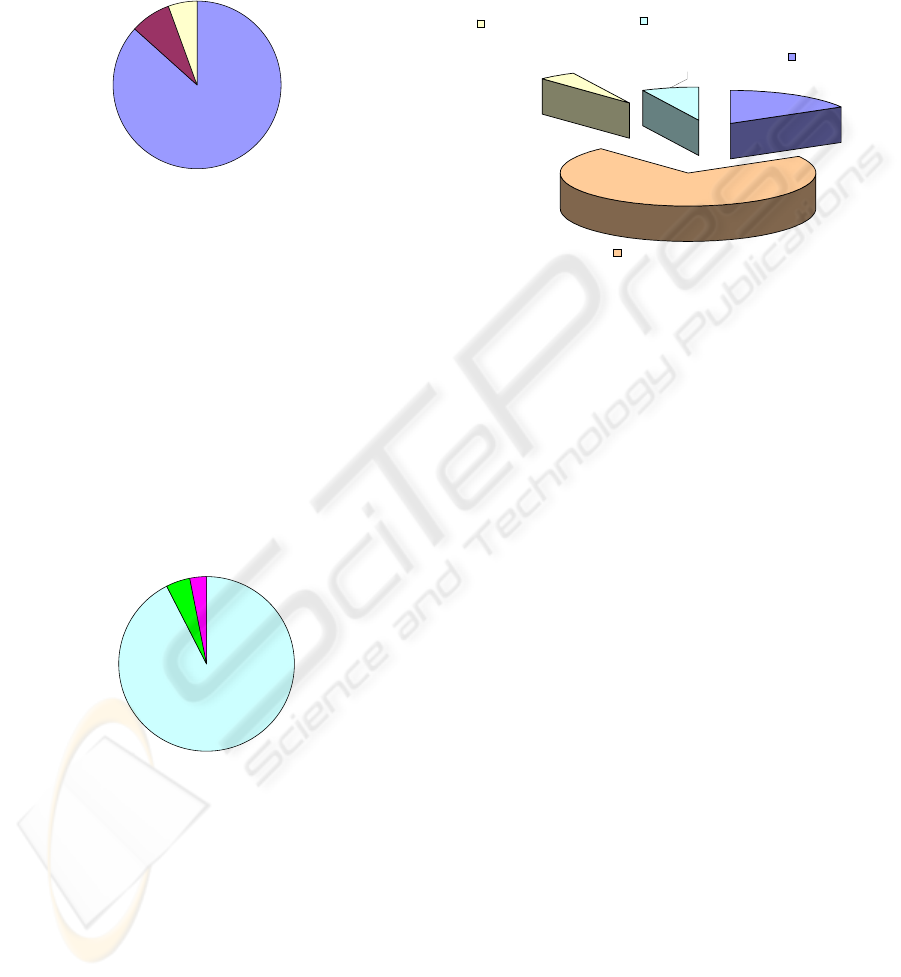

Figure 2: Phishing sites by hosting country July 2006.

Figure 2 shows that the USA (47%) and Great

Britain (19%) were the top two most popular

countries hosting phishing sites for the July 2006

sample. This indicates that ISPs in the USA and the

UK are either more prone to hosting phishing attacks

due to insufficient defense against phishing

activities, or due to the vast numbers of ISPs

available in these two countries. Additionally, in

some 11% of cases, multiple sites were used. We

believe this indicates a trend towards the next-

generation of botnet-style hosting for phishing sites,

which have been growing seen since this sample was

gathered.

Time of day is another possible fingerprint,

When we examined Tuesday 18 July 2006 in detail

(Table 8), 12 phishing incidents were observed,

starting at 4.01am and continuing to 8.59am, then

followed by a break of about ten hours, followed

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

152

again by three from 6.44pm to 7.39pm. This may be

deliberate targeting of the victim users when they

access their systems in the morning and first thing in

the evening, or may again indicate the working

schedule of the phishers themselves.

Win32, 4, 8%

Linux, 3, 6%

Unix, 46, 86%

Figure 3: Operating system used by the phishing sites July

2006.

Time of day is another possible fingerprint,

When we examined Tuesday 18 July 2006 in detail

(Table 8), 12 phishing incidents were observed,

starting at 4.01am and continuing to 8.59am, then

followed by a break of about ten hours, followed

again by three from 6.44pm to 7.39pm. This may be

deliberate targeting of the victim users when they

access their systems in the morning and first thing in

the evening, or may again indicate the working

schedule of the phishers themselves.

Others, 2, 3%

Microsoft, 3,

5%

Apache, 61,

92%

Figure 4: Web server types used by the phishing sites July

2006.

In the October corpus, a new style of attacks

were identified for a particular phishing group not

seen in July. The group used a URL that spoofed

"victimbank.com" and had a hostname component of

"confirmationpage". They assigned each individual

phishing URL a subdomain that was tied to an

Internet address of a compromised computer under

the phisher’s control. When a victim clicked on a

link in the phishing e-mail, they would be routed

through the compromised PC to the correct phishing

Web page, depending on a special code specified in

the e-mail link. The methodology resembles that

used by the “RockPhish” group mentioned earlier.

4.2.2 E-mail Header Information

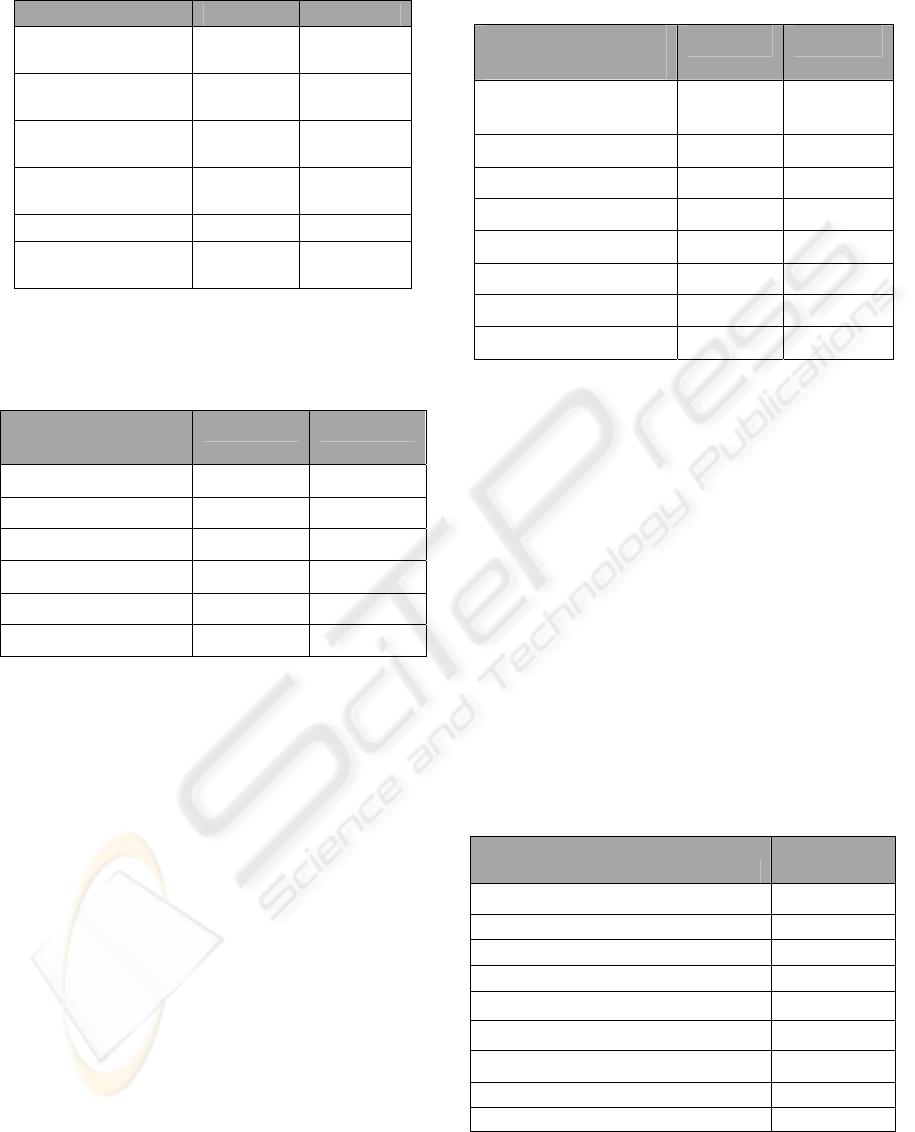

Figure 5: X-Mailer values used in the July 2006 phishing

incidents.

Our analysis showed that while values such as IP

address source were interesting, they did not prove

to be useful for classifying groups. However, some

less obvious features were unexpectedly more useful

for grouping. Two particular values associated with

a particular group, the X-Mailer and the Date field

time zone were observed only in phishing e-mails

and never in any valid e-mail in the sample data

(which included more than 500,000 spam messages).

Figure 5 shows that Microsoft Outlook Express

version 5 and 6 were the most widely used X-Mailer

platform in the July phishing incidents. This result

was confirmed in the October corpus, as shown in

Table 2. One abnormality observed in the July

corpus was the frequent occurrence of an invalid

value (71%). 7,291 messages in the October corpus

with this particular value and 3,680 of those

messages targeting other victim organizations and

were associated with other illegal activities, such as

job scams.

Thus, the X-Mailer value appeared to be the main

fingerprint of the spam tool used by this particular

group. Google searches using the X-Mailer values

were subsequently used to identify other phishing

messages posted to the web and newsgroups. As

these values are still in use by phishing groups

today, we are precluded from providing further

details.

Microsoft CDO

for Exchange

2000,

2 ( 5%)

Microsof

t

Outlook Express

5,

3 (7%)

Microsof

t

Express 6.00,

7 (17%)

Invalid Value

30 (71%)

FORENSIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PHISHING - Petty Theft or Organized Crime?

153

Table 2: X-Mailer values in the October 2006 corpus.

X-Mailer Frequency Percentage

Microsoft Outlook

Express 210,958 27.36%

Microsoft Office

Outlook 58,339 7.57%

Internet Mail

Service

8,885 1.15%

MIME-tools 5.503

(Entity 5.501) 4,102 0.53%

SquirrelMail/1.4.3a 2,971 0.39%

Calypso Version

3.30.00.00 2,181 0.28%

4.2.3 E-mail Subject, Sender and other Text

Values

Table 3: Some commonly used Sender Address.

Commonly used

Sender address

Frequency Percentage

victimbank 53 75%

access@ 14 20%

Support@ 12 17%

Security@ 8 11%

Account@ 4 6%

internet@ 2 3%

Other e-mails values examined and used for

grouping were the subject and sender values. While

many phishing e-mails spoof the victim institution,

some do use other e-mail addresses. As shown in

Table 3, when spoofing the organization’s e-mail

domain, there were many choices of username to

spoof from the victim institution e.g..

support@victimbank.com, admin@victimbank.com,

security@victimbank.com, or

access@victimbank.com. While all these values are

subject to copycatting, they can be used in

conjunction with other more highly discriminating

values to facilitate grouping.

Table 4 shows the result of our analysis in the

Subject line from the July corpus. A majority of the

phishing e-mail subject lines used a Base-64

encoded character string (41%). This indicates a

program-generated subject line.

Table 4: Commonly used words in the subject line in the

July 2006 phishing incidents.

Commonly used word

in the subject line

Frequency Percentage

Base64 encoded

string

29 41%

Update 21 30%

Access 15 21%

Agreement 15 21%

Account 13 18%

Victim Bank 11 15%

Security 11 15%

Internet 7 10%

Another commonly used word is “update”

(30%) as contained in the subject: “Security Update

Request” and “Agreement Update”. The third most

commonly used word is “access” (21%), as

contained in the subject: “Online Access Agreement

Update”. The other commonly chosen words were

“Account” (18%), “victim-bank Internet banking

security message” (15%). 220,494 distinct subject

line values out of the total 770,998 e-mails were

found in the October 2006 corpus. 43% of the total

corpus contains a delivery failure notification in the

subject line. The October 2006 corpus also

confirmed that phishing Group 1 was active in

launching the attack with 3,611 messages (0.5% of

the corpus) were identified targeting this particular

financial organization.

Table 5: Job offer scam launched by Group 1 in the

October 2006 corpus.

Subject

# of

Instances

Job offer from BestTrade Group 108

Job offer from SelfTrade Group 101

Job offer U.F.I.S. PE 96

Job offer from BidsTrade Group 59

Job offer from BidsLoan Group 44

Job offer from UnelTrade Group 35

Job offer from SelfPower Group 28

Job offer from MetaBrand Group 14

Job offer from XepsTrade Group 3

Interestingly, by using the signatures left by

Group 1 in their phishing messages, another 3,280

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

154

messages were identified targeting other financial

organizations including CitiBank, PayPal and Bank

of America. It is logical to expect that money mule

job scams of a kind have been perpetrated in

conjunction with phishing attacks, again indicating a

high level of organization through diversified

criminal activity. This was confirmed with another

488 messages that started with "Job offer" in the

message subject (

Table 5). Moreover, we have also

identified 238 ‘Nigerian 419 scam’ messages having

the same signatures that belong to Group 1. These

results indicate that phishing attacks are related to

other crimes committed using e-mail. We also found

6,523 (0.9%) messages contained the subject line:

“victim Bank official message”. This matched one

of the key characteristics of the Group 6 phishers,

although the subject lines found in the October

corpus differed slightly with those found in the July

corpus. Further investigation confirmed that these e-

mails were originated from the same group. Other

characteristics that confirm our grouping for this

particular Group 6 are:

• The e-mail structure is text/html;

• The DCC Fuz2 value for the e-mail content

is equal to a particular value;

• The From field contains the common plain

text “victimbank security”; and

• The Sender field contains a particular user

value.

4.2.4 DCC Fuz2 Checksum

The Distributed Checksum Clearinghouse (DCC) is

an anti-spam content filter (http://www.dcc-

servers.net/dcc/) used by SMTP servers and mail

user agents to detect spam messages. We applied

DCC Fuz2 checksum on all messages in the October

corpus and identified 560,801 distinct values. Some

of the most frequent messages are listed in table 6.

We found that both Group 1 and Group 2 phishing

gangs were active in October 2006. Group 2 had

launched separate attacks against this organization

and another victim bank.

Table 6: Most frequent messages identified by DCC Fuz2

checksum in the October 2006 corpus.

Most frequent messages in

October corpus

Frequency

Group 1 messages targeting

this victim bank

3611

Group 2 messages targeting

the victim bank

2842

"Replica" Spam messages 1657

Group 2 messages targeting

another victim bank

1626

ED Spam 1395

4.2.5 Spelling and other Typographic Errors

Another interesting aspect of many phishing e-mails

is their grammar and spelling. A standard feature of

many early phishing e-mails were their very poor

grammar and spelling. Common errors include

“statment”, “acount”, “fullfil” and “automaticly”.

Many of these errors have now disappeared, but they

are still a useful value to identify groups. In addition

to clear spelling, grammatical errors and other

typographic errors, unusual terminology is another

useful grouping value. An example of this is a

reference found in one group’s e-mails to a fictional

entity the “National Anti-fraud Organisation of

Australia” (Group 4). We found that a specific

typographical error occurred in many phishing

messages e-mails that could not be identified by a

spellchecker. This is a strong indicator for the

grouping of phishing messages to a particular group.

Using that particular word to search in Google found

that this particular word appeared in e-mails related

to other activities such as the Nigerian 419 Scam and

the eBay (VOLUME 2 of 3 Share) scam.

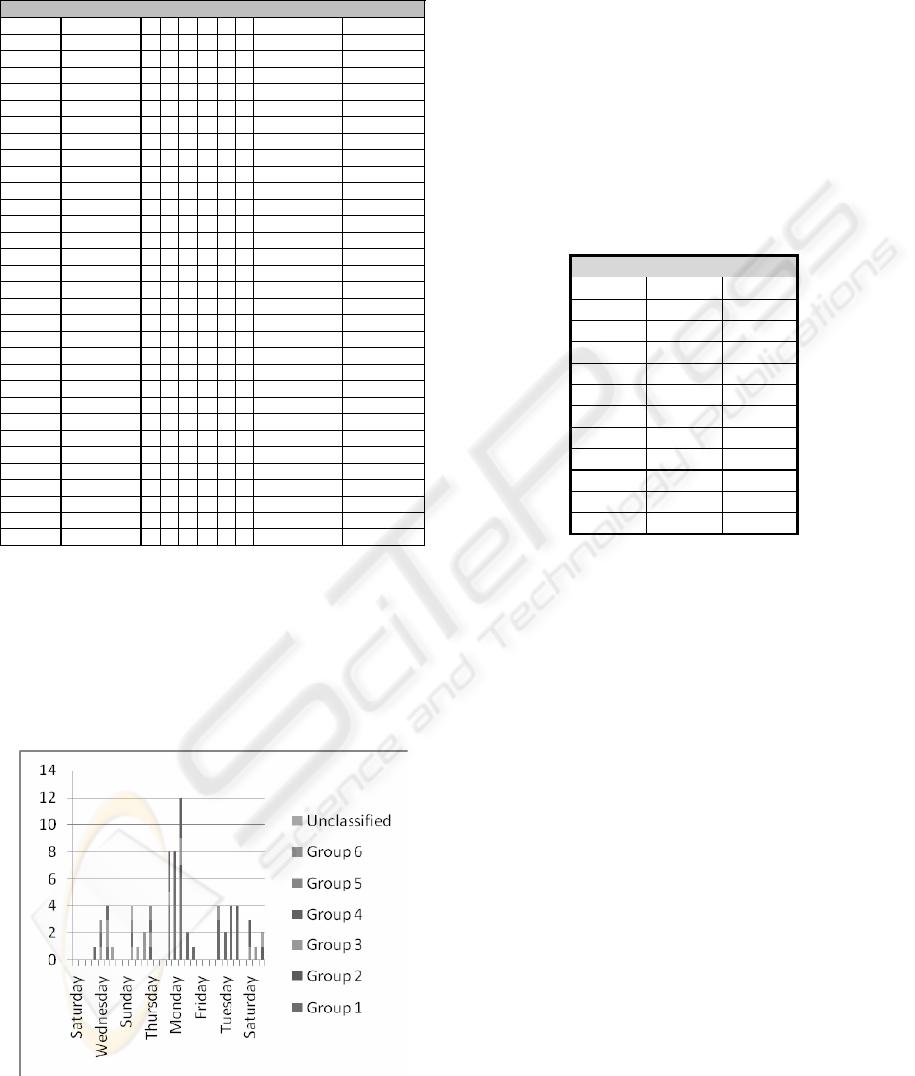

4.3 Phishing Incidents by Date and by

Group

Table 7 shows that phishing incidents seemed to

occur at the midweek dates (Tuesday, Wednesday

and Thursday), and the peak value occurred at a

Tuesday (12 incidents). Most of the weekly peak-

incidents occurred on Thursdays. From Table 7 and

Figure 6 we observed that some groups concentrated

their attacks over shorter periods. For example, of

Group 1’s 30 attacks, 29 occurred over two weeks in

a period of five days, followed by a period of four

days in the following week. In contrast, Group 3’s

13 attacks occurred over nearly the whole month on

11 different days.

FORENSIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PHISHING - Petty Theft or Organized Crime?

155

Table 7: Numbers of phishing incidents by day from

Saturday 1 July 2006 to Monday 31 July 2006 categorized

by identified groups.

DATE DAY 1 2 3 4 5

6

UNCLASSIFIED DATE TOTALS

1-Jul-06 Saturda

y

0

2-Jul-06 Sunda

y

0

3-Jul-06 Monda

y

0

4-Jul-06 Tuesda

y

11

5-Jul-06 Wednesda

y

111 3

6-Jul-06 Thursda

y

121 4

7-Jul-06 Frida

y

11

8-Jul-06 Saturda

y

0

9-Jul-06 Sunda

y

0

10-Jul-0

6

Monda

y

111 1 4

11-Jul-0

6

Tuesda

y

11

12-Jul-0

6

Wednesda

y

22

13-Jul-0

6

Thursda

y

1111 4

14-Jul-0

6

Fr i da

y

0

15-Jul-0

6

Sa t u r d a

y

0

16-Jul-0

6

Sunda

y

413 8

17-Jul-0

6

Monda

y

44 8

18-Jul-0

6

Tuesda

y

61 2 3 12

19-Jul-0

6

Wednesda

y

22

20-Jul-0

6

Thursda

y

11

21-Jul-0

6

Fr i da

y

0

22-Jul-0

6

Sa t u r d a

y

0

23-Jul-0

6

Sunda

y

0

24-Jul-0

6

Monda

y

31 4

25-Jul-0

6

Tuesda

y

22

26-Jul-0

6

Wednesda

y

44

27-Jul-0

6

Thursda

y

31 4

28-Jul-0

6

Fr i da

y

0

29-Jul-0

6

Sa t u r d a

y

12 3

30-Jul-0

6

Sunda

y

11

31-Jul-0

6

Monda

y

112

Group Totals

30 3 13 18 3 2 2 71

Another interesting aspect is the virtual

weekend enjoyed by the phishers. While there are

attacks on Saturdays and Sundays, there appears to

be a break between weeks for most attacks because

of the 11 incident free days for the month, they all

fall in the Friday to Monday period. This indicates

an organized work schedule, confirming the result

obtained by Ramzan and Wừest (2007).

Figure 6: Numbers of phishing incidents by day from

Saturday 1 July 2006 to Monday 31 July 2006 categorized

by identified groups.

Time of day is another possible fingerprint,

When we examined Tuesday 18 July 2006 in detail

(Table 8), 12 phishing incidents were observed,

starting at 4.01am and continuing to 8.59am, then

followed by a break of about ten hours, followed

again by three from 6.44pm to 7.39pm. This may be

deliberate targeting of the victim users when they

access their systems in the morning and first thing in

the evening, or may again indicate the working

schedule of the phishers themselves.

Table 8: Phishing incidents on 18 July 2006 by header

received time (converted to AEST), date and phishing

group.

TIM E DAT

E

GROUP

4:01:01 18-Jul-06 1

4:35:04 18-Jul-06 1

6:03:03 18-Jul-06 1

6:43:27 18-Jul-06 1

7:09:24 18-Jul-06 4

7:49:56 18-Jul-06 4

8:06:37 18-Jul-06 3

8:32:51 18-Jul-06 2

8:59:10 18-Jul-06 4

18:44:4

5

18-Jul-06 3

19:25:13 18-Jul-06 1

19:39:39 18-Jul-06 1

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have shown how a criminal

investigation methodology based on authorship

analysis and fingerprinting can be used to classify

phishing e-mails into a small number of discrete

groups. While most spam e-mails do not aim to

misrepresent their identity, this is the goal for

phishing e-mails.

To summarize, some 6 distinct groups were

responsible for the overwhelming majority of attacks

identified in both sets of data. 86% of all attacks

originated from of these groups. In many cases, the

distinguishing features of phishing e-mails were

found in other e-mail crimes such as money

laundering and 419 scams. This indicates that

phishing groups are diversified criminal enterprises,

each using their own distinctive modus operandi to

commit crimes across a wide spectrum. Other

indicators of organized work activity included taking

breaks at weekends, and launching attacking during

daytime hours from the geographical source regions.

On the technical side, the use of multiple servers to

provide fail-over during attacks indicates a growing

trend for a sophisticated distributed computing

WEBIST 2008 - International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

156

capability on the same level as legitimate

organizations. As discussed in the introduction, only

data from a single target in the financial services

area was used to develop the investigation

methodology. However, anecdotal evidence suggests

that most banks and financial institutions are

experiencing qualitatively similar attacks. Our first

task in generalizing our findings will be to replicate

the results across data sets from other institutions. Of

course, practical difficulties exist in obtaining this

data from organizations that keep their operational

security issues secret.

A second major challenge is to validate the

findings across further time periods, and get a sense

of the variation in both group composition and

features used. One can anticipate a high-level of

turnover in the features used, however, if they are

not revealed in the public arena and/or incorporated

into anti-spam signature databases, then our

experience is that the values are not altered.

We are also investigating methods that enable

automated profiling of phishing attacks by groups in

real time and be built in to commercial tools for law

enforcement based on classification techniques from

natural language processing (Watters,2002). We

intend to extend the approach by utilizing

hierarchical clustering to identify more complex

patterns of heredity among the different techniques

being used by each group.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by a major Australian

financial institution that wishes to remain

anonymous for operational security reasons.

REFERENCES

Alleged Phishing and Organized Crime Group Arrests.

Technology News Daily 2006.

Card fraud losses continue to fall 14 March 2007 (on-line)

http://www.apacs.org.uk/media_centre/press/07_14_0

3fraud.html

Abad, C., The Economy of Phishing: A Survey of the

Operations of the Phishing Market, 2005.

Chandrasekaran, M., Narayanan, K., and Upadhyaya, S.

Phishing E-mail Detection Based on Structural

Properties. In Proceedings of the NYS Cyber Security

Conference. 2006

[de-Vel, O. Mining E-mail Authorship In Proceedings of

the Workshop on Text Mining, ACM International

Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data

Mining (KDD'2000). 2000

de-Vel, O., Anderson, A., Corney, M., et al., Mining E-

mail Content for Author Identification Forensics.

SIGMOD: Special Section on Data Mining for

Intrusion Dection and Threat ANalysis, 2001

Dhamija, R., Tygar, J.D., and Hearst, M. Why Phishing

Works. In Proceedings of the CHI 2006. Montréal,

Québec, Canada, 2006

Fette, I., Sadeh, N., and Tomasic, A. Learning to Detect

Phishing E-mails. In Proceedings of the 16th

international conference on World Wide Web (WWW

2007).p.649 - 656:ACM Press, 2007

Jagatic, T., Johnson, N., Jakobsson, M., et al., Social

Phishing, School of Informatics Indiana University, 12

December, 2005

Jakobsson, M., Modeling and Preventing Phishing

Attacks, School of Informatics Indiana University at

Bloomington, 27 October, 2005

James, L., Phishing Exposed. Rockland MA: Syngress

Publishing, 2005

McMillan, R. 'Rock Phish' blamed for surge in phishing,

(on-line) http://www.infoworld.com

/article/06/12/12/HNrockphish_1.html

Naraine, R. Return of the Web Mob, April 10, 2006 (on-

line)

http://www.eweek.com/article2/0,1895,1947561,00.as

p

Ramzan, Z. and W¨uest, C. Phishing Attacks: Analyzing

Trends in 2006. In Proceedings of the Fourth

Conference on E-mail and Anti-Spam (CEAS 2007).

2007

Stamp, P., Penn, J., Adrian, M., et al., Increasing

Organized Crime Involvement Means More Targeted

Attacks, Forrester Research, October 12, 2005

Watters, P.A., Discriminating English word senses using

cluster analysis. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics.

9(1): 77-86,2002

FORENSIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PHISHING - Petty Theft or Organized Crime?

157