IS THERE A ROLE FOR PHILOSOPHY IN GROUP WORK

SUPPORT?

Roger Tagg

School of Computer and Information Science, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes SA 5095, Australia

Keywords: Collaborative Computing, Philosophy, Information Systems Methodology.

Abstract: There appears to be evidence that much potential IT support for group work is yet to be widely adopted or

to achieve significant benefits. It has been suggested that, in order to achieve better results when applying IT

to group work, designers should take more notice of modern philosophies that avoid the so-called "Cartesian

Dualism" of mind separated from matter. It is clear that group work support is more than a matter of

automating formal procedures. This paper reviews the question from the author’s lifetime of experience as a

consultant, academic and group worker; proposes some models to address some of the missing perspectives

in current approaches; and suggests how future efforts could be re-orientated to achieve better outcomes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recent years have witnessed much soul-searching in

the field of Information Systems (IS). This was

highlighted in (Hirschheim and Klein, 2003), which

talked about a crisis in IS. Although the obvious

symptoms have been the bursting of the dot.com

bubble and a major decline in student enrolments,

the authors saw the more serious issue as the failure

of IT and the internet to introduce a “rational-critical

discourse”. In other words, IT support has

concentrated on the mechanistic facilitation of

business and government activity, and not on

improving human communication and participation.

In attempts to counter this shortcoming,

philosophy has sometimes been invoked as an

influence in a number of IS innovations. For

example, Organisational Semiotics (Stamper, 1973)

can be traced back to the “pragmatism” of Peirce,

see e.g. (Wiener, 1958); and Language Action

Perspective (LAP) (Medina-Mora et al, 1992) to

“Speech Acts” (Searle, 1964) – and, according to

(Nobre 2007a, 2007b) to Heidegger’s “Being and

Time” (Heidegger, 1926).

Philosophy is also the theme of (Mingers and

Willcocks, 2004), which contains a collection of

authors’ views on the relevance of philosophy to IS.

However philosophy rarely makes for easy reading

by IS and IT practitioners, especially in the case of

Heidegger.

(Medina-Mora et al, 1992) stated that “We

encounter the deep questions of design when we

recognise that in designing tools we are designing

ways of being. By confronting these questions

directly, we can develop a new background for

understanding computer technology – one that can

lead to important advances in the design and use of

computer systems.”

In the case of using IT to support group work,

(Nobre, 2007a) suggested that most of our current

efforts are too biased towards “structuralist and

cognitivist interpretations of group behaviour”.

Instead, we need to “study collaboration and

coordination in innovative ways that explore the

social embeddeness and embodiness of human

meaning and knowledge creation”.

Many useful insights have also been offered by

other authors, for example (Checkland and Scholes,

1999; Kent, 1978; Mumford, 1995; Ciborra, 2002)

and the proponents of Activity Theory, e.g.

(Engeström et al, 1999; Constantine, 2007). These

publications do not require us to hack our way

through the jungle of Heidegger’s terminology.

However as (Lyytinen, 2004) points out, LAP

has not managed to become part of the IT

mainstream, and the same can be said for many

other innovations of IS and IT researchers. There is

therefore an unsolved question of how we, as

academics, analyst/designers and software

developers, can actually help to realize the potential

improvements of these innovations.

89

Tagg R. (2008).

IS THERE A ROLE FOR PHILOSOPHY IN GROUP WORK SUPPORT?.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 89-96

DOI: 10.5220/0001677200890096

Copyright

c

SciTePress

The present author is basing this paper not only

on the literature, but also on his experience in 45

years of work in Information and Management

Science (Tagg, 2008). The paper continues by first

analysing some of the things that are often said to be

wrong with current practice in group work. It then

considers the potential value of some philosophical

(or quasi-philosophical) ideas. Two examples of

additional conceptual models are then proposed,

which try to address some otherwise missing

perspectives that a philosophical approach may

uncover. These are followed by a short conclusion,

which includes some suggestions for future changes

in approach.

2 THE CURRENT ILLS OF

WORKING IN GROUPS

Many articles, especially in the popular press,

suggest that even with all technologies we have,

projects involving collaboration between humans

have low success rates, implementation delays or

serious teething troubles. Whistle blowers are not

encouraged, and a credibility gap arises between the

messages one is told and what one observes or finds

out. Taking a philosophical approach, we should try

to address the reasons, and not pretend that group

work follows some ideal pattern.

2.1 Overload

In 45 years in the workplace, this author has noticed

a relentlessly creeping number of hours one is

expected to work per week, and a greater proportion

of working time being spent on non-core work.

Examples are regulatory compliance, data collection

and measurement, quality assurance, switching from

one job to another, attending to ever-expanding

volumes of email - and last but not least, “backside

covering” – trying to cover oneself against blame for

when things go wrong.

Overload is discussed in the literature, e.g.

(Whittaker and Sidner, 1996). (Kirsh, 2000) also

discusses the cognition problems of frequently

switching focus. Fragmentation – the problem of not

getting a clear run to get things done without

interruption - has also been recognized by e.g.

(Czerwinski, 2006; Tungare et al, 2006).

For many information workers, a relentless

worsening of overload has outpaced any gains from

using IT. A Canadian study (Wilson et al, 2000)

reports that some workers are experiencing

depression, alienation and detachment at work. This

in turn leads to failure or poor quality in what the

group is trying to achieve.

2.2 Too Much Methodology

(Ciborra, 2002) strongly argues that the worlds of

management and IT have become preoccupied with

methodologies, theories, models and procedures -

and, as a consequence, measurement. He claims that

in many cases, there has been little or no measurable

gain from all this effort.

(Kent, 1978) takes a similar view, and warns

against the tendency to try to force reality to fit our

models. Part of the problem arises because, for those

of us who are academics, our promotion prospects

depend on getting papers published; the chances of

getting a paper accepted by referees – if it has a

simple formal model in a single coherent area - seem

higher than for a paper proposing a more

interdisciplinary idea. Likewise, consultants often

need to have a technical or management bandwagon

which one can jump on in order to get business.

Especially with the more creative types of group

work, an emphasis on procedures seems counter-

productive. Instead the emphasis ought to be on

selecting from available tools and resolving issues

by discourse. However too many tools can bring

problems just like too many methodologies. There is

a limit to what we can add to the users’ toolboxes,

especially if they give contradictory results. The rate

at which users can absorb new tools and

methodologies is also limited.

2.3 Too Much Measurement

It has been observed for many years that each time a

bad outcome happens, management culture tends to

demand a new control system to ensure it doesn’t

happen again, with the consequent increase in the

data that has to be collected. As a result, humans in

groups pay more attention to ensuring acceptable

values of these measures - rather than achieving the

primary business function of the group.

An interesting statistic in Australia is that the

administrators, as a percentage of all university staff

have increased from 40% to 60% in 8 years (and

even this does not recognise the mass of

administrative and reporting work that has been

thrown onto academics). When challenged, the

Education minister commented that if we want best

value for the education dollar, then we need this

level of control. But absolute student achievement

standards are not measured.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

90

In fact we are seeing a philosophy develop that

says that what we can’t or don't measure isn’t

important. Our promotion prospects seem tied only

to achieving figures.

2.4 Legacy Management Culture

Some problems of group work derive from the

darker side of common management “culture”.

• “Seat of the Pants” style, reacting to crises.

Management often takes the line “don’t give

me all that stuff – my intuition works best”.

This may be valid - but only up to a point.

• Divine Right of Managers – “management

should have the right to manage” – in other

words, “I want to run this group like an army –

do what I say without question”.

• Deterministic management, i.e. the delusion

that we only have to set a plan, or put a

procedure in place, and it will just happen. Risk

management is sometimes considered, but often

leaves out many of the ways in which things

can go wrong.

• Micro management and over-control – the idea

that we can get more deterministic results if we

impose tighter control.

• Throwing burdens on front line workers – the

idea that the job of applying control can,

without penalty in lost time and work

fragmentation, simply be thrown onto the front

line workers.

• Organisational Learning (or lack of it) – the

idea that if we ourselves didn’t invent an idea,

it can’t possibly be applied to our situation.

• Pressure on the human – if things aren’t

happening as we want, just applying more

person-to-person pressure will solve it.

2.5 Human Frailty

There is a group of ills that relate to the tendencies

towards expediency and bravado that exist in most

of us.

• We are driven by headlines – maybe because of

time pressures, we only read or hear the

headlines, and don’t look into the “why” or

read between the lines.

• Spin – a profession seems to have grown up in

always finding words to make black sound

white. However spin eventually leads to

credibility gaps, and is hence unsustainable –

people eventually realizing that things aren't

like what they were told.

• Believing one’s own Bullshit – not seeing that

much of what we say is probably nonsense, but

wanting to maintain our prestige or pride.

• The Backs to the Wall syndrome – when things

are going badly, there is a higher motivation to

improve, but also to cheat.

• The Golden Age syndrome – when one holds a

commanding competitive position, e.g. in

military, manufacture, raw materials, fuel, or

entertainment terms, there is more temptation to

rest on one’s laurels and pretend it’s all due to

our superior culture (e.g. Rome, British

Empire?).

• Litigiousness – resorting to lawyers and hence

spending big sums so as to be seen to be

“fighting all the way”. This not a level playing

field – the big groups can always get away with

spending more on lawsuits than the small

groups.

• Jargon and general language misuse - we are

tempted to hide behind specialist jargon, which

often seems geared to limiting the contribution

of fellow group members who don’t have that

speciality. The result is often uncertainty and

mistrust.

2.6 The Failure of IT so Far

Within the research group of which this author is a

member, (Shumarova and Swatman, 2007) found in

the literature little evidence of practical evaluation of

many CSCW (Computer Supported Cooperative

Work) initiatives, except on use of the main

commercial groupware tools, such as Lotus Notes or

Microsoft Outlook, or simple communication aids.

There have been a number of suggested

improvements to groupware, e.g. (Bellotti et al,

2004; Muller et al, 2004), but these prototypes have

only been evaluated done using temporary “interns”

and then seemingly abandoned. At the time of

writing, there have been few signs of these ideas

becoming part of mainstream commercial tools.

More fundamentally, (Hirschheim and Klein,

2003) think the whole field of Information Systems

is in crisis. Their argument is that the internet has

failed to introduce an improvement in “rational-

critical discourse”. Instead, it has become simply a

tool for supporting commercial buying and selling; a

medium for publication by government, industry and

pressure groups, or a data communications medium

to support formal processes. Applications have been

restricted to short-term efficiency.

IS THERE A ROLE FOR PHILOSOPHY IN GROUP WORK SUPPORT?

91

3 THE RELEVANCE OF IMPLIED

OR EXPLICIT PHILOSOPHIES

3.1 The Implied Philosophies of

Current Business Practice

Even the natural language we use to converse with

other humans assumes a culture and a default

philosophy, derived from a melange of inherited

religion and scientific rationalism. It is possibly at

this level, rather than in formal systems, where

Heidegger or others can maybe take us.

Using small groups has often been advocated as

a good approach to collaborative activity. They

maintain motivation better and can resist imposed

vested interests. However they do not address

competitive power or economies of scale; and, if

priorities change, a group may be reluctant to

disband itself.

Current business practice favours large

hierarchies, e.g. armed forces and multinationals.

Success depends on a clear command structure,

implying subordination of the individual to the big

group's aim. This may be assisted by a prescribed

religion, a mission statement or company slogans.

Management in such groups has become a key

concept, e.g. (Drucker, 1954) - although this is often

perverted by human egos and hidden agendas. Strict

hierarchies have had a generally successful run over

the course of history, but today they may fail

because people today no longer accept things just

because someone tells them - they can find a

different view in a Blog or Wiki.

3.2 The Implied Philosophy of Science

and Technology

The contrasting philosophy of science and

technology, sometimes derided as Cartesian

Dualism, has had a major influence on the evolution

of modern life and society. It can be seen as a

reaction to the monopolizing of all knowledge and

interpretation by religious and monarchic

hierarchies. The essence is that reality is only that

which we can observe or prove logically. Scientific

methods have been applied to Management and IS in

the form of such initiatives as Procedure Manuals,

O&M, OR, Computer Systems (including

programming, systems analysis and databases),

Business and Information Strategy Planning, BPR

and Workflow.

However as everyone knows, failures are

frequent and human commitment is often half

hearted. This may be because the underlying

theories and models depend on gross simplifications

of reality, and often attempt to force reality to fit the

process logic. This is particularly true of methods for

designing systems that can be implemented on

computers. UML, for example, may be a good fit for

object oriented technology, but it misses many

perspectives that should be considered to ensure

success of the total system.

3.3 The Implied Philosophy of the

Semantic Web and Related

Ontology

This includes such concepts as Knowledge

Management, Organisational Learning and Artificial

Intelligence. Any ontology has to be based on some

or other approach to structuring the real world.

However much of the technology is still dependent

on inexact natural language, and is complex to build,

maintain and understand.

In spite of this, ontologies are one of this

author’s topics of recent interest, and it is critical to

a current project to develop usable software support

to categorise the mass of data that assails us, and to

enable us to cope with our overload.

Table 1 shows a model I have been working on

recently, which gives priority to the many

relationships that do not often get considered in most

IT-based models.

Table 1: Relationship Types in this author’s proposed

Ontology Structure.

Major Group Minor Group examples

Classification

"is-a" type

Specialisation, Generalisation,

Instantiation, Membership

Composition

"part-of" type

Inclusion, Containment, Bounding,

Ingredient

Apposition

"is-with" type

Connection, Interfacing, Fitting, Holding,

Owning, Proximity, Familiarity

Comparison

"is-like" type

Similarity, Differentiation, Identification,

Relative space/time position

Processing Sequence, Dependency, Simultaneity,

Derivation, Condition, Repetition

Transformation Production, Manufacturing, Consumption,

Metamorphosis, Movement

Interaction Communication, Transaction, Agreement,

Contention, Reaction, Competition,

Cooperation, Trust

Planning Desire, Intention, Responsibility,

Limitation, Requirement, Design,

Commitment, Dreaming, Fearing

Representation Naming, Representing, Observation,

Recording, Imagining, Signification

Measurement Measurement, Estimation, Prediction

Reasoning Interpretation, Summarisation,

Justification, Causation, Solution,

Understanding, Hypothesis

Utilisation

"is-useful-for" type

Purpose, Potential

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

92

This relationship-oriented ontology is subject to five

basic rules:

1 a relationship is a "thing", just as an entity is

2 a relationship can participate as a slot in

another relationship

3 a relationship can have attributes

4 a relationship can have many "slots"

5 any classification of relationships is fairly

arbitrary, and each type has aspects of one or

more parent types

Potential relationship slots include two or more

things that are being primarily related, agent or

actor, theoretical basis or assumption, date-time-

place (possibly "from" and "to" and "reported"), and

the source of the alleged relationship ("says who?').

In my ontology I separate the "lexical" text

strings (or other signs) - that enable context to be

recognised - from the ontology classes and instances

themselves. I have also attempted to take notice of

Mereology – the study of the many variations in

“part-of” relationships, e.g. (Lewis, 1990).

However if any these models become too

prescriptive, they too may still fail, as they become

too diffuse and complex for any automation, and at

same time too mechanistic to recognise all

experience and motivation.

3.4 The Philosophies behind

Organisational Semiotics,

Language Action Perspective

and Activity Theory

Among conscious attempts to introduce philosophy

into IT, Organisational Semiotics (Stamper, 1973)

proposed a "ladder" with 6 steps - with Pragmatics

and Social World added as extra steps above the

normal ontological ones of Empirics, Syntactics and

Semantics. He also proposed a notation "Semantic

Normal Form" and a methodology "MEASUR".

More recently, (Cordeiro and Filipe, 2004b)

proposed a Semiotic Pentagram Framework.

Language Action Perspective (LAP) claims a

philosophy derivation from the earlier Speech Act

theory. It is already available in group support in the

form of the Action Workflow tool (Medina-Mora et

al, 1992). Methodologies based on LAP include

DEMO Business Process Modelling (Dietz, 1999)

and BAT (for Inter-organisational coordination)

(Goldkuhl, 2006).

Activity Theory was originally proposed by

Russians (e.g. Leont'ev, 1977) and since championed

by (Nardi, 1996) and (Engeström et al, 1999). This

has less of a strictly philosophical basis but

consciously models more perspectives than most IT

methodologies. The work of the FRISCO group

(Hesse, 1999) and the Theory of Organised Activity

(Holt, 1997) should also be mentioned here.

All these theories seem totally creditable as

contributions to improving IS development, and

their best features can possibly, as suggested by

(Cordeiro and Filipe, 2004a) be combined. But the

question is, why have they not become part of the

mainstream? According to (Lyytinen, 2004), the

reason for the failure of LAP is a mixture of not

having been enshrined in a widely used commercial

package, a failure in the diffusion of information and

the inability of the existing knowledge networks to

cope. As an ex-consultant, I ask myself "could I go

out to clients with these theories and expect to get

enthusiastic involvement from client personnel?"

3.5 Heidegger and "Grand Name"

Philosophies

Even as a non-philosopher, I can see many

advantages in considering philosophies such as

utilitarianism and pragmatism in relation to

supporting group work.

Figure 1: An Attempt to Diagram some of the Main

Concerns in Heidegger’s Ontology.

• being-in-the-world

• thrownness,

facticity

• temporality,

historicity

• spatiality,

directionality,

de-distancing

• nearness

• resoluteness

• disclosedness,

truth

• attunement

• interpretation

• significance

• discourse

• lan

g

ua

g

e

• falling prey

• innerworldly things

• idle talk

• curiosity

• ambiguity

• remoteness

• thingliness

• obstinacy

• irresoluteness

• obtrusiveness

• conspicuousness

authentic inauthentic

• familiar tools

• family

• instincts

• emotions

• measurements

• conscious observations

• calculations

• theories

• models

What is at

hand

What is

objectively

present

“Da-sein”

- being there,

existentiality,

care

IS THERE A ROLE FOR PHILOSOPHY IN GROUP WORK SUPPORT?

93

But, as presented in the literature, they do not

appear to me to answer the challenge I have just

stated. I am also unsure how well they address the

inevitable need for "trade-offs" between a multitude

of different utility measures.

As an illustration, I have attempted in Figure 1

below to show diagrammatically the essence of

some of what is said in Being and Time (Heidegger,

1926), as interpreted via (Scott, 2007) and (Heath,

2003). However I would claim that any attempt to

bring Heidegger directly into most of what we do as

system designers will not be accepted, because of

the problem of intelligibility of the language used.

The only sensible course would seem to let the

developers of the next generation in IS

methodologies take what advantage they can of the

best of these ideas, just as Dietz, Stamper and others

have tried to do. But the lessons regarding adoption

that were raised by Lyytinen in 3.4 above must still

be noted.

4 TWO SUGGESTED

ADDITIONAL CONCEPTUAL

MODELS

This section introduces two possible models that

address some of the additional perspectives

suggested by a more philosophical approach, based

on this author’s reading and working experience.

4.1 The Cycle of Human Endeavour in

Groups

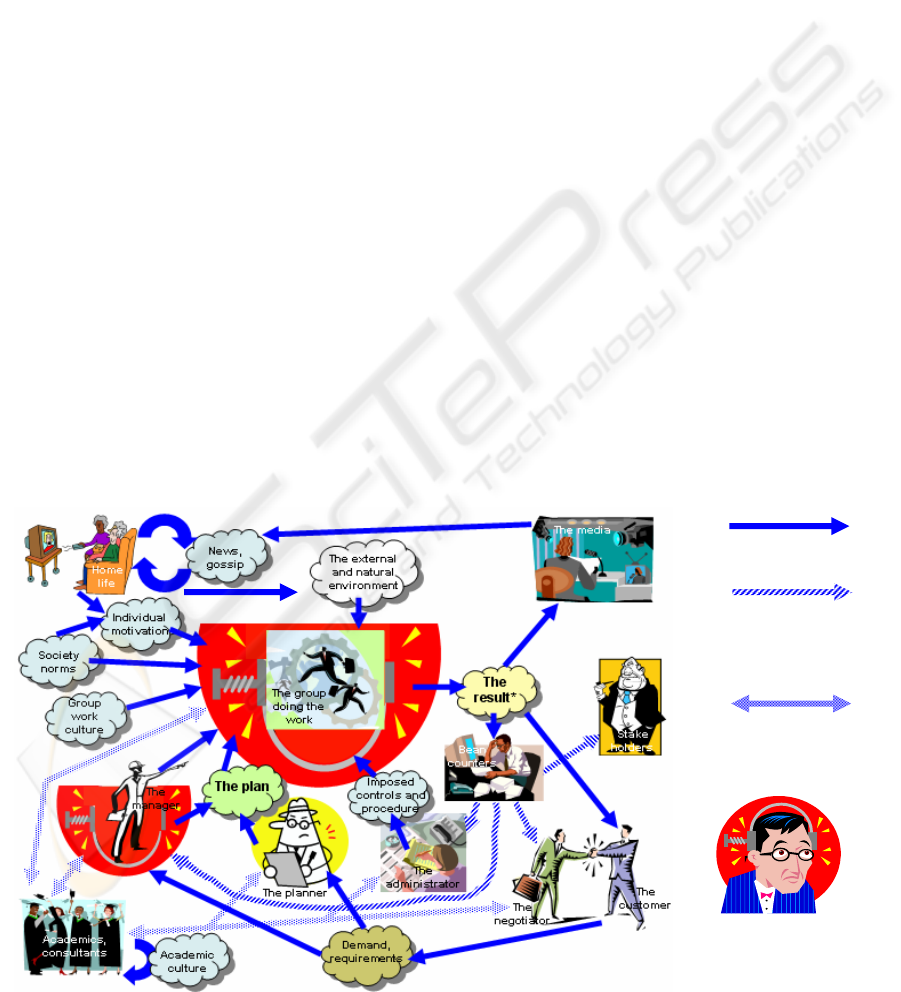

Figure 2 shows a rich picture illustrating this

author’s view of the cyclic nature of human

endeavour where a group of humans, possibly aided

by machines, is working to a plan in order to

produce a result. Clearly the group doing the work

has to balance a diverse range of influences. The

screw-tightened vice represents the “squeeze” of

pressure on the group, which partly reflects pressure

on their manager. The asterisk in the “The Result”

cloud is there to remind the reader that results are

not only what the bean counters measure – they

reflect whatever reaction anyone affected has to both

the outcome and the way it was done. The customer

reacts to product or service quality, but the

stakeholder and manager may only react to the data

the organisation deems it should measure.

If things do not go well, then pressure from the

stakeholders, customers or the media pressurises the

organisation (or external regulators) to introduce

extra measurement and control procedures. These

rarely ever get rolled back, so there is a gradual

proliferation of overheads and “dumbing down” of

the group’s contribution.

This example shows how in some of the

considerations that are addressed by the philosophies

in sections 3.3 to 3.5 above can be brought into the

designer's consideration. The challenge for the

designer is to recognize which of these

Key:

Direct influence

Reporting of

measurements and

other data

Consultancy and

methodology

improvements

Pressure on the

group or

individual

Figure 2: Cycle of Human and Group Endeavour.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

94

Figure 3: Overlapping Roles and Motivations.

considerations are critical to the success of any

proposed support system - something that asking the

people involved does not always easily reveal.

4.2 The Structure of Roles and

Motivations

Figure 3 is a Venn-style diagram that shows a wide

selection of roles that humans in a group may play

(many of them simultaneously). What motivates

individuals in a group is therefore a complex matter.

Some examples of motivation that may apply are

ensuring personal safety, reducing uncertainty,

saving enough for a rainy day, building a strong base

for later, achieving ambitions, completing

milestones, enjoying the present, providing for one’s

children, getting promotion, gaining fame, seeing

procedures observed, achieving targets, reducing or

avoiding pain or embarrassment, not to be shown up

as a loser, avoiding climb-downs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

As the last two models demonstrate, we should

include the "missing perspectives" in our models.

Projects and systems may fail because they do not

take these perspectives into account. Examples are

that a solution may simply take too long to achieve;

control and data collection turns out too expensive;

or genuine concerns do not get raised. Sometimes,

they are left out because they are not considered

measurable, or not on the list of KPIs (key

performance indicators) - but they can still cause

failure.

We should accept that human nature may be

changeable, but only very slowly. We should

deliberately encourage a “Plan B” discipline, and

recognize humans’ need for an “escape route”. We

should understand how to concentrate on getting the

critical things right, rather than correctly following a

procedure. We should understand that we, as agents

of change, are also part of the problem. We should

also understand that language may be critical in the

communication between, say designers in two

organizations A and B, or between users, technical

specialists, decision makers (and those that have

influence over them) within the same organisation.

We should try and make work enjoyable and

“fun”. The chairman of one of my former employers

once declared that the mission of the company was

“Interesting Jobs for Interesting People”. Maybe the

financial “bottom line” should be a constraint – not

the be all and end all.

Our common motivation as humans is that we all

have to make the best of our brief life here on earth.

As the subtitle of Townsend's second book “Further

Up The Organization” (Townsend, 1988) says,

“How Groups of People Working Together for a

Common Purpose Ought to Conduct Themselves for

Fun and Profit.”

Those of us who are academics need to take

Lyytinen's lesson (Lyytinen, 2004). Theories and

models are not enough unless there is a path for

knowledge diffusion and clear motivators for users

to adopt them. Of course, we are "part of the

problem" and are driven by our own motivations,

e.g. to "publish or perish" and bring PhDs to

completion.

All our efforts to support group work to date are

built on some implicit or explicit philosophy.

IS THERE A ROLE FOR PHILOSOPHY IN GROUP WORK SUPPORT?

95

However any additional invocation of philosophy

should not be directed towards preparing more

models and theories, but to remind us of what

perspectives we are not yet covering.

Philosophies such as those from the "grand

names" are probably too far removed from what we

in IT have to do from day to day, although it would

certainly help if they were easier to understand.

REFERENCES

Bellotti, V., Dalal, B., Good, N., Flynn, P., Bobrow, D.

and Ducheneaut, N., 2004. What a To-Do: Studies of

Task Management. In CHI Conference, Vienna.

Checkland, P. and and Scholes, J., 1999. Soft Systems

Methodology in Action, Wiley.

Ciborra, C., 2002. The Labyrinths of Information, Oxford

University Press.

Constantine, L., 2007. From Activity Theory to Design

Practice. Keynote presentation, ICEIS Conference,

Madeira.

Cordeiro, J. and Filipe, J., 2004a. Language Action

Perspective, Organizational Semiotics and the Theory

of Organized Activity - A Comparison, DEMO

Conference.

Cordeiro, J. and Filipe, J., 2004b. The Semiotic Penta-

gram Framework. In Organisational Semiotics

Conference.

Czerwinski, M., 2006. From Scatterbrained to Focused: UI

Support for Today’s Crazed Information Worker. In

SIGIR Workshop on Personal Information

Management, Seattle.

Dietz, J., 1999. Understanding and Modeling Business

Processes with DEMO. In Entity Relationship

Conference, Paris.

Drucker, P., 1954. The Practice of Management, Harper

and Row.

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., Punamäki, R.-L. (Eds).

1999. Perspectives on activity theory. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Heath, T., 2003. The Question of the Meaning of Being -

Making Sense of Martin Heidegger's Being and Time.

http://website.lineone.net/~tmheath/Being_&_Time_

Notes/ (accessed 16 Nov 2007)

Heidegger, M., 1926. Being and Time, translation 1996 by

Stambaugh, J., State University of New York Press.

Hesse, W. and Verrijn-Stuart, A., 1999. Towards a Theory

of Information Systems: The FRISCO Approach. In

Report of ISCO-4 Conference, Leiden.

Hirschheim, R. and Klein, H., 2003. Crisis in the IS Field?

A Critical Reflection on the State of the Discipline.

Journal of AIS, October.

Holt, A., 1997. Organized Activity and Its Support by

Computer, Springer.

Goldkuhl, G., 2006. Action and Media in

Interorganizational Interaction. CACM 49(5).

Kent, W., 1978. Data and Reality, AuthorHouse.

Kirsh, D., 2000. A Few Thoughts on Cognitive Overload,

Intellectica.

Leont'ev, A. N., 1977. Activity and consciousness. In

Philosophy in the USSR, Problems of Dialectical

Materialism. Progress Publishers. http://

www.marxists.org/archive/leontev/works/1977/leon19

77.htm (Accessed 13 March 2008)

Lewis, D., 1990. Parts of Classes, Blackwell.

Lyytinen, K., 2004. The Struggle with Language in the IT

- Why is LAP not in the Mainstream? In 9

th

Inernational Working Conference on LAP on

Communication Modelling.

Martin, J., 1989. Strategic Information Planning

Methodologies, Prentice Hall.

Medina-Mora, R., Winograd, T., Flores, R. and Flores, F.,

1992. The Action Workflow Approach to Workflow

Management Technology. In CSCW Conference.

Mingers, J. and Willcocks, L., 2004. Social Theory and

Philosophy for Information Systems, Wiley

Muller, M., Geyer, W., Brownholtz, B., Wilcox, E. and

Millen, D., 2004. One-Hundred Days in an Activity-

Centric Collaboration Environment based on Shared

Objects. In CHI Conference, Vienna.

Mumford, E., 1995. Effective Systems Design and

Requirements Analysis: the ETHICS Method,

Macmillan.

Nardi, B, 1996. Activity Theory and Human-Computer

Interaction, chapter 1 of Activity Theory, MIT Press.

Nobre, A., 2007a. Action, Language and Social Semiotics.

Poster at Workshop on Computer Supported Activity

Coordination, ICEIS Conference Madeira.

Nobre, A., 2007b. Organizational Learning and

Heidegger’s Ontology. Poster at ICEIS Conference,

Madeira.

Roget, P., 1996. Roget's Thesaurus, Penguin.

Scott, A., 2007. Heidegger's Being and Time.

http://www.angelfire.com/md2/timewarp/heidegger.ht

ml (accessed 16 Nov 2007).

Searle, J., 1969. Speech Acts, Cambridge University Press

Shumarova, E. and Swatman, P., 2007. Organizational

Impact of Collaboration Information Technologies.

Working paper, CreWS (Creative Work Support)

research project, University of South Australia

Stamper, R., 1973. Information in Business and

Administrative Systems, Wiley.

Tagg, R., 2008. Personal Home Page, http://

www.cis.unisa.edu.au/~cisrmt/ (accessed 13 March 2008)

Townsend, R., 1988. Further Up the Organisation.

HarperCollins.

Tungare, M., Pyla, P., Sampat, M. and Perez-Quiñones,

M., 2006. Defragmenting Information using the

Syncables Framework. In SIGIR Workshop on

Personal Information Management, Seattle.

Whittaker S. and Sidner C., 1996. Email Overload:

Exploring Personal Information Management of Email.

In ACM Conference on Computer-Human Interaction.

Wiener, P (Ed), 1958. Charles S Peirce: Selected

Writings, Dover.

Wilson, M., Joffe, R. and Wilkerson, B., 2000. The

Unheralded Business Crisis in Canada - Depression at

Work. GPC Canada, http://www.mental

healthroundtable.ca/aug_round_pdfs/Roundtable

report_Jul20.pdf (accessed 16 Nov 2007).

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

96