SOFTWARE OFFSHORE DEVELOPMENT

A Criteria Definition for References Models Comparison

Leonardo Pilatti and Jorge Luis Nicolas Audy

Computer Science College, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Porto Alegre, Brazil

Keywords: Global Software Development, Offshore Development, Reference Models.

Abstract: Software development has been a challenge. This complexity significantly increases when company team

member are working in an offshore environment. The need for a set of processes increases after every

project, including those to organize the development strategy. Reference models, maturity models and

frameworks can be found in literature trying to solve this problem. However, few comparative analysis have

been done in order to validate the appropriate solution. The objective of this paper is to elaborate and define

a set of criteria to perform a comparative analysis of the main global software development reference

models, focusing the offshore development, having as basis an extensive literature review and a case study

in industry. The case study was conducted in two different sites in Brazil.

1 INTRODUCTION

Managing information technology projects is

become more complex over the years. Because the

project’s size, requirements even more complex,

time to deliver the product and the growth in the

software development team. Teams are now spread

between countries and located in different time

zones. People are even more getting used to interact

with co-workers from different cultures and beliefs.

One of the major benefits is the flexibility in having

almost non-stop work around the globe – when the

teams are strategically located. For companies it has

being an interesting experience since they increase

their profits margin over time since can have access

to qualified workers from third world country by on-

third their values (Carmel et al, 2002).

Variants of the Agile or Extreme Programming

methodologies are applied during the software

conception, developing and testing. It is common

that these companies also have a proprietary code

library about their softwares. However, the majority

of this library only exists in theory. There aren’t

processes or procedures to support it (Reponen,

2002).

It is necessary for the site and organization in

define a structure that supports the development

process. It is not a maturity model, rather than, a

static structure that can be used in order to define

and better compound the methods used to build the

software, use better use the policies and distributes

their business in order to maximize the offshore

development strategy (Khan, 2003).

This paper/poster presents criteria composition

for references models in the global software

development area. A comparative analysis is also

done between them, based in the criterions. A case

study was conducted in two different organizations

in order to increase the criteria’s accuracy and

generalization. The research method is exploratory

and based in extensive literature review.

2 THEORETICAL BASE

2.1 Global Software Development

As some authors pointed the global software

development is characterized by having one (or

both) of the elements involved: time and distance

(Coar, 2004). Companies can work locally or

distributed. Working in a distributed environment,

time and/or distance are present as elements that

differentiate both of them. Working in a global

software development approach denotes a

revolutionary way for a company in conducting its

business. Managers and directors are even more

considering global variables when defining and

running global projects. Time zones, cultural

differences, communication, trust, among others,

212

Pilatti L. and Luis Nicolas Audy J. (2008).

SOFTWARE OFFSHORE DEVELOPMENT - A Criteria Definition for References Models Comparison.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 212-215

DOI: 10.5220/0001686402120215

Copyright

c

SciTePress

need to be well aligned in other to not let the team

members loose their focus. It is known that this

strategy is delineated by positive or negative forces.

2.2 Offshore Development

The Offshore Development is strategy used by

companies in other to take the benefit from others

site countries. The projects and services can be

reallocated in a specialized-different-country-site

where a high level of specialization can take place

(Carmel et al, 2002).

Countries like Russia, Brazil and India has been

playing a major role in such strategy, mainly

because the low taxes and low labour cost in hiring

employees from these locations (Gopalakrishnan,

2003). Some of the key factors include cost

reduction, working with specialized workers world-

wide and the capability in implementing follow-the-

sun methodology (working 24 hours a day, round the

world) (Khan, 2003).

2.3 Reference Models for Offshore

Development

2.3.1 By Kishore et al (2003)

In (Kishore, 2003) the author defines a framework

creating a relationship between the service provider

and the service requester. Know as Four

Outsourcing Relationship Types (FORT), it defines

dimensions and presented factors that need to exist

between the two involved parts (requester and

provider) in order to achieve the completion of the

service.

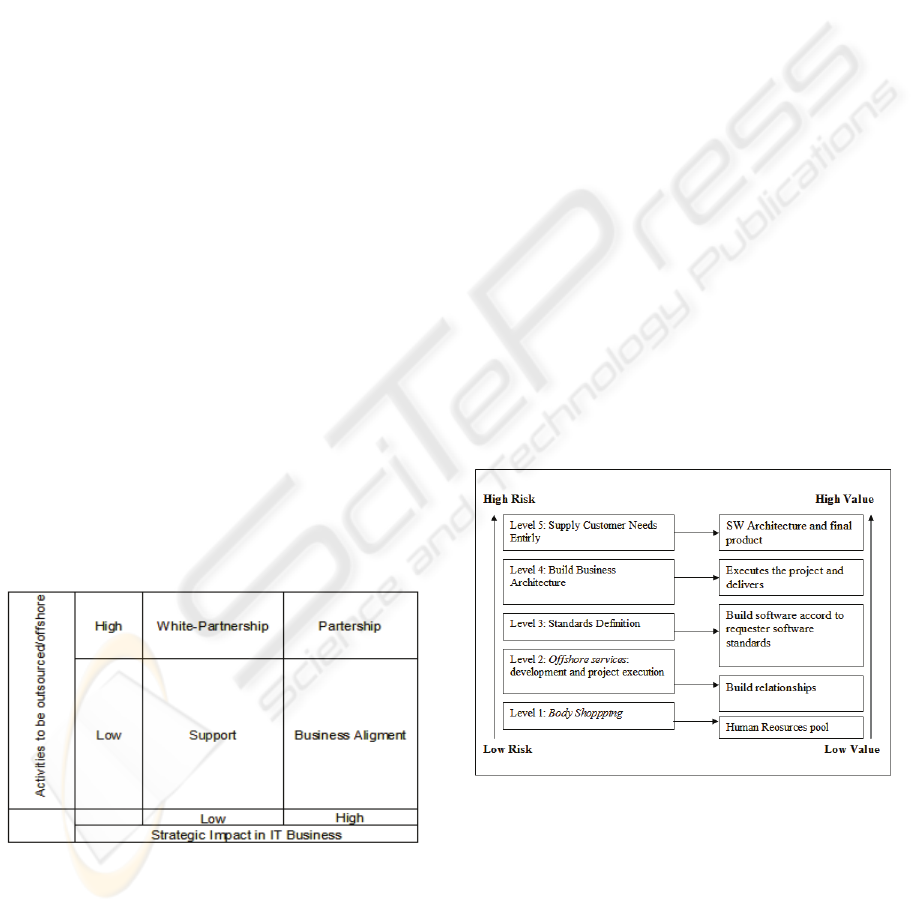

Figure 1: FORT Framework.

Figure 1 shows its dimensions: the strategic

impact of the outsourced business and the work

amount being outsourced.

This reference model has the objective to

enumerate dynamic and static aspects that will exist

between the service requester and service provider.

It is important for managers and directors in

understand how the relationship with the service

provider organization can grow and where it is

during a specific moment in time. All these analysis

were done always considering the strategic impact

that the service provider has over the service

requester. Furthermore, the model intends to

establish a clear link between both organizations and

how they impact each other during time, as well

their impact in terms strategic aspects.

2.3.2 By Khan et al 2003

In (Khan, 2003) the author identifies offshore

organizations by the type of work provide. He

classifies organizations involved in offshore

development as service providers or requesters.

Similar as (Kishore, 2003), however including risks,

benefits and drawbacks of the relationship they

develop. During time, the involvement and work

methods are being specialized in the service

provider, in order to attend the requester demand.

This model maps the possible relationships along

time that the organization may have. As higher is the

cooperation between them, higher is the aggregated

value and higher is the risk for the requested core-

business. Services were mapped between the types

of involvement that the requester has with the

provider and were related in figure 2.

Figure 2: Reference Offshore Model by (Khan, 2003).

As can be noted there is a direct relationship

between aggregated value and associated risk that

the provider brings to the requester. Has complex the

type of the service, as risky can be for the service

requester. Following this concept, the author

represented the model in a scale in five levels, from

one to five, containing the possible types of Works

SOFTWARE OFFSHORE DEVELOPMENT - A Criteria Definition for References Models Comparison

213

and their respective impacts for the requester. As

higher the risk, higher the aggregated value, level 5.

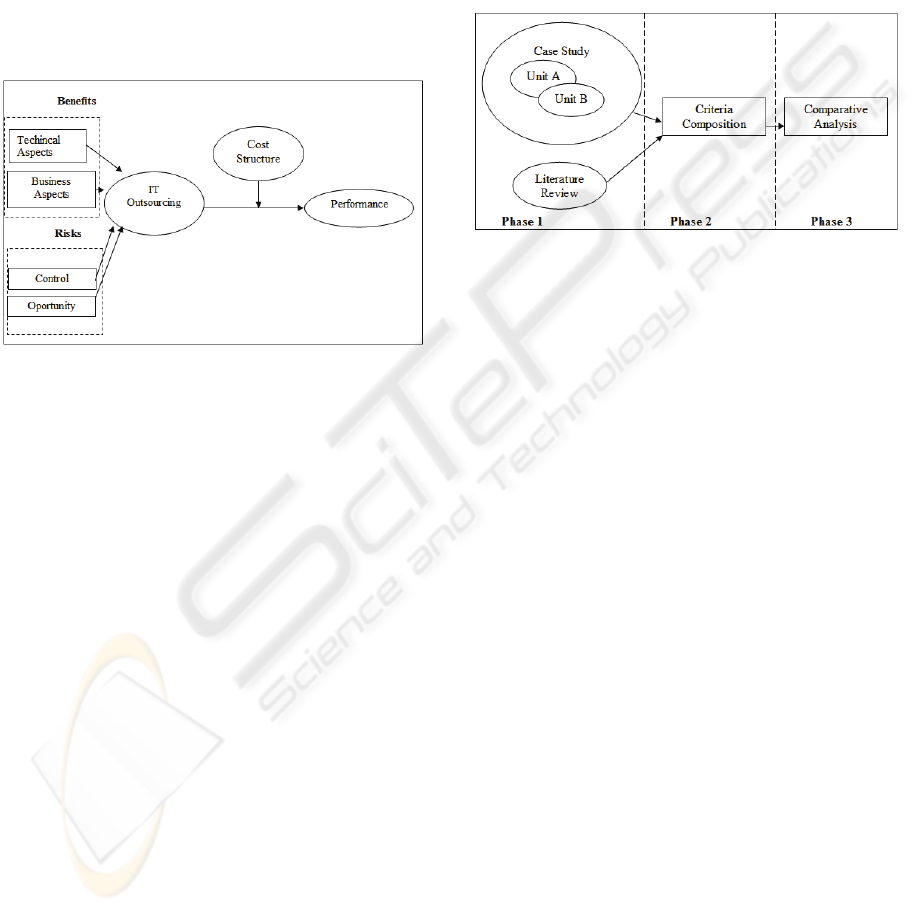

2.3.3 By Loh & Venkatraman (2002)

The authors developed a conceptual modelling to

offshore organizations using a set of criterions as

being determinants to the company’s performance.

Using the offshore strategy, in the conducted studies

the authors create a relationship between the benefits

and risks when choosing a subsidiary or company

when offshoring heir services. Figure 3 presents

denotes the model concept.

Figure 3: Offshore Reference Model for organizations

(Loh & Venkatraman, 2002).

2.3.4 By Song et al (2003)

In the work from (Song, 2003) a reference model is

created in order to help the decision maker to which

offshore company the work should be sent. Similar

to works from (Khan, 2003) and (Kishore, 2003), the

relationship between service provider and requester

is a key factor in the offshore strategy. However to

which country the service is sent is here a

fundamental factory too. It is important to note that

social and technical aspects are delimitated by

countries’ culture, and hence, defines if the

implementation was successful or not. Other social

elements, such as economics, political and cultural,

between the provider and the requester were also

considered as fundamental in this model.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

As described in (Yin, 2001), this study is

characterized as being mostly exploratory, involving

literature review about the main offshore references

models and findings from a case study. These

findings were important in order to compose the

criterions. The research method was presented in

figure 4 and related the phases as described below.

This research was organized in four (3) phases.

First (Phase 1) was a literature review about the

main offshore development maturity models, the

sites will be referenced by letters as “Unit A” and

“Unit B”.

In the step (Phase 2) was the criteria elaboration

and in third step (Phase 3) a comparative analysis

from the reference models was done.

Figure 4: Research Method.

4 CRITERIA DEFINITION AND

COMPOSITION

The process to compose the criterions started by the

reference models analysis found in literature. A

caution was taken in order to consider only elements

that could be observed in all models; otherwise the

comparison would be pointless. For each defined

criteria, the case study finding proven if it could be

finally used as formal criteria in the model analysis.

All the criterions were presented by table 1. It also

presents: The criteria itself; A reference from where

in literature, or in case study findings, or both it was

found; And the explanation for its use. An acronym

“CsA” is used to define the finding from unit A and

“CsB” for unit B.

Defining criterions is not a trivial task and raise

questions in considering such criterions and not

other ones. During the analysis only criterions that

could be found in all models were consider.

In order to perform the comparative analysis, a

combination between the defined criterions and the

models were defined and presented in table 2. These

combinations have in the header the criterions

defined in this section. In the first column all

reference models found in literature were listed.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

214

Table 1: Offshore Reference Criteria Composition.

5 COMPARATIVE ANALYSES

The analysis was verified in order to validate if the

model attended the criteria. When it was satisfied –

meaning that it was found in the model – a symbol

(√) marks the intersection column between the

model and the criteria. If the symbol is not present,

the model does not attend the criteria.

The reference offshore model defined in (Song,

2003) was the one with lower criteria marks (3 from

8 defined criterions). However, the model from

(Khan, 2003) and (Kishore, 2003) attended 5 from 8

criterions. Finally, the reference model from (Loh &

Venkatraman, 2002) attends 6 from 8 criterions and

was the one with higher number of satisfied

criterions. Still accord with this description it can be

used as guideline to implement software engineering

practices and process, meaning that it is

complementary and serve as additional model to

maturity models. As from the case study findings it

was noted that the offshore models should be

complementary to other maturity models already

present in the industry. It was noted that (Loh &

Venkatraman, 2002) refers to this implementation

and guideline as well.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis from Offshore Reference

Models.

An important finding is that the most missing

criterions were criteria 5 (Type of Service

Segmentation) and criteria 7 (Technical Aspects).

Even criteria 5 being identified in “CsA”, it lacks in

the majority of the models.

6 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

It is important to note that the criterions have a

higher scope since were found in case studies. From

the interviews, the comments were considered when

elaborating the criterions as well. Some of these

elements had direct impact in the software quality,

as enumerated by some managers – the social and

relationship aspects between the requester and the

provider.

Results from this work contribute for the

offshore area – as comparisons between such models

were not found in previously researches. The case

study brought practical validation and important

findings from managers and offshore units.

As future researches this study will continue to

expand the applicability and involve other offshore

unit’s as well different models. Quantitative

analysis, including surveys would also increase the

generalization.

REFERENCES

Carmel, E., Agarwal, Ritu, 2002. The Maturation of

Offshore Sourcing of Information Technology Work.

MIS Quarterly Executive, vol. 1, no. 2, 12pp (65-77)

Coar, Ken., 2004. The Sun Never Sets on Distributed

Development. ACM Proceedings, 6pp

Gopalakrishnan, S.; Kochikar, V. P.; Yegneshwar, S

(2003). The Offshore Model for Software

Development: The Infosys Experience. ACM

Proceedings, 2pp

Khan, Naureen, et al., 2003. Developing a Model for

Offshore Outsourcing. In: Ninth Americas Conference

on Information Systems, 8pp

Kishore, Rajiv; Rao, H. R.; Nam, K.; Rajagopalan, S.;

Chaudhury, A (2003). A Relationship Perspective on

IT Outsourcing, Communications of the ACM, vol. 46

no 12, 6pp

Loh, Lawrence; Venkatraman, N (2002). An Empirical

Study of Information Technology Outsourcing:

Benefits, Risks and Performance Implications, IEEE

Software Proceedings, 12pp

Reponen, Tapio, 2002. Outsourcing or Insourcing? ACM,

12pp

Song, Jaeki; Jain, Hemant K (2003). Cost Model for

Global Software Development. ACM Proceedings,

3pp

Yin, Robert., 2001. Case Study: Methods and Planning.

Sao Paulo: Bookman, 205 pp.

SOFTWARE OFFSHORE DEVELOPMENT - A Criteria Definition for References Models Comparison

215