CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS TO EVALUATE

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OUTSOURCING PROJECTS

Edumilis Méndez, María Pérez, Luis E. Mendoza and Maryoly Ortega

Processes and Systems Department – LISI, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas, Venezuela

Keywords: Outsourcing, Information Technology, Critical Success Factor, Business Process.

Abstract: Nowadays, a large number of companies delegate their tasks to third parties in order to reduce costs,

increase profitability, expand their horizon, and increase their competitive capacity. The level of success of

such contracting and related agreements is influenced by a set of critical factors that may vary depending on

the type of project addressed. This article proposes a model of Critical Success Factors (CSFs) to evaluate

Information Technology Outsourcing (ITO) projects. The model is based on the ITO state-of-the-art, related

technologies and different aspects that affect ITO project development. Altogether, 22 CSFs were

formulated for data center, network, software development and hardware support technologies.

Additionally, the model proposed was evaluated using the Features Analysis Case Study Method proposed

by DESMET. The methodology applied for this research consisted of an adaptation of the Methodological

Framework for Research of Information Systems, including the Goal Question Metric (GQM) approach. For

model operationalization, 400 metrics were established, which allowed measuring CSFs and ensuring model

effectiveness to evaluate the probability of success of an ITO project and provide guidance to the parties

involved in such service.

1 INTRODUCTION

Information Technology Outsourcing (ITO) is an

increasingly widespread practice among companies.

Given that the scope and complexity of Information

Technologies (IT) are constantly increasing, several

companies are less prone to carry the burden of

Information Systems (IS) internal development, and

are considering Outsourcing to make a more

efficient use of resources and lay the basis for

increasing IT value (Lee et al., 2003). Hence, the

importance of knowing which aspects may influence

successful relations between the client company and

the ITO project provider.

Accordingly, this article proposes a model

consisting of 22 Critical Success Factors (CSFs) for

evaluating ITO projects, focused on technology-

related factors, including 400 metrics for model

operationalization. This model provides guidance to

support optimum performance for ITO practice and

has an evaluation structure based on measurements

of well-defined factors, which allows registering

project data through the years. It allows not only

specific evaluations, but also the follow-up and

analysis of variations and trends.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research used the Methodological Framework

for Research of Information Systems (Pérez et al.,

2004). The adaptation of the Methodological

Framework for this work consists of eleven steps:

1) Documentary and bibliographical research;

2) Background Analysis; 3) Formulation of the

Objectives and Scope of the Research; 4) Adaptation

of the Methodological Framework; 5) CSF Model

proposal following GQM approach; 6) Analysis of

Context; 7) Application of the DESMET

Methodology (Kitchenham, 1996); 8) Model

Evaluation; 9) Results Analysis; 10) Proposal

Refining; and 11) Conclusions and

Recommendations.

3 BACKGROUND

In order to achieve a successful ITO, certain

practices known as CSFs should be included. Austin

176

Méndez E., Pérez M., E. Mendoza L. and Ortega M. (2008).

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS TO EVALUATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OUTSOURCING PROJECTS.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - ISAS, pages 176-181

DOI: 10.5220/0001686801760181

Copyright

c

SciTePress

(2002) defines CSFs as critical areas where

satisfactory performance is required for the

organization in order to achieve its goals. For the

purposes of this article, a CSF is defined as any

activity, task or requirement, where its correct

performance contributes to meet the objectives of

successful ITO projects. Such factors may be

considered as critical to the extent their no

compliance divert parties from meeting their

expectations. Many activities might be considered as

CSFs depending on the area and perspective

involved. However, efforts invested in this research

are aimed at identifying technology-related CSFs.

Several sources describe different types of CSFs

that are overlapped or complemented depending on

the approach used. Dhillon (2000) discusses the

possibility of extracting critical activities from a

business management perspective, while Lovells

International Law Firm (2006) analyzes ITO from a

legal perspective based on the large experience

gained from their clients’ activities.

The ITO Governance Model of Technology

Business Integrators (TBI) discusses a business

management approach (Bays, 2006), but contrary to

Dhillon (2000), it provides a rather practical than

theoretical analysis for this phenomenon. Also,

Robinett et al. (2006) list a series of CSFs that point

to a business-related approach, which is much more

technical than managerial. This perspective is based

on IBM’s experience as IT leader and its integral

business solutions policy.

However, the most recent ITO trend points to

more restricted and specialized definitions for each

contracted service. This implies a reduction in the

spectrum of activities considered for each contract,

including multilateral contracts with different

providers, instead of traditional mega-contracts with

a single provider. This new Strategic Out-Tasking

model fostered by Cisco Systems Inc. (Brownell et

al., 2006) promises a revolution in the ITO market

with high profitability margins and superior service

quality.

4 CSF MODEL PROPOSAL

The model proposed model is based on the concepts

presented in Section 3. Table 1 shows a list of 22

CSFs resulting from the comparison of CSFs

identified by different authors and specific models

consulted, namely: (a) College of Business

University of Nevada (Dhillon, 2000), (b) Lovells

International Law Firm (2006), (c) Cisco Systems

Inc. Strategic Out-Tasking Model (Brownell et al.,

2006), (d) TBI ITO Governance Model (Bays, 2006)

and (e) Center for Digital Government & IBM

(Robinett et al., 2006). This comparison allowed the

identification of differences and similarities among

these approaches to consolidate the proposal on the

four IT aspects aforementioned (O’Brien, 2005):

data center, network, software development and

hardware support.

A breakdown of CSFs is provided for each

technology used. For data center and network

technologies, the model lists several operations

involved such as design, implementation,

administration, maintenance, support, among others.

For software development technologies, the model

relies solely on development, while hardware

technologies focus only on support.

Each CSF acts in different way depending on the

technology involved. However, some factors may

act in a similar manner regardless of the technology

implied, namely CSF 11, 12, 20 and 21. Particularly,

for CSF 11 “Establish multilateral agreements”, if a

client chooses to contract several providers and not

to depend on just one, a structured process should be

performed to select a group of organizations with

expertise in the technologies and methodologies

required by the contract, and whose interests do not

conflict with those of the client. A provider with

outstanding expertise must be selected for each

service, giving priority to those providers who

effectively served the same client in the past.

CSF 15 “Establish exclusivity agreements for

key areas” is not considered for network technology,

since the client would hardly commit the provider to

grant it a certain degree of exclusivity.

The defined CSFs are a strong indicator of the

possibilities of success of an ITO project. However,

to ensure efficient use of these CSFs for project

monitoring and related decision-making processes,

all answers need to be converted into measurable

information. Therefore, operationalization of this

model was made using the GQM approach (Basili,

1992).

In this regard, metrics associated to each

question defined on the CSFs allowed a detailed

evaluation. Answers provided by experts to each

question and their impact on each CSF were

converted into a numeric scale in order to determine

the overall performance of a certain type of project.

Registering this information over the years might

help establishing a benchmark for the median of ITO

project performance within the market. Thus, each

project performance might be compared against the

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS TO EVALUATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OUTSOURCING PROJECTS

177

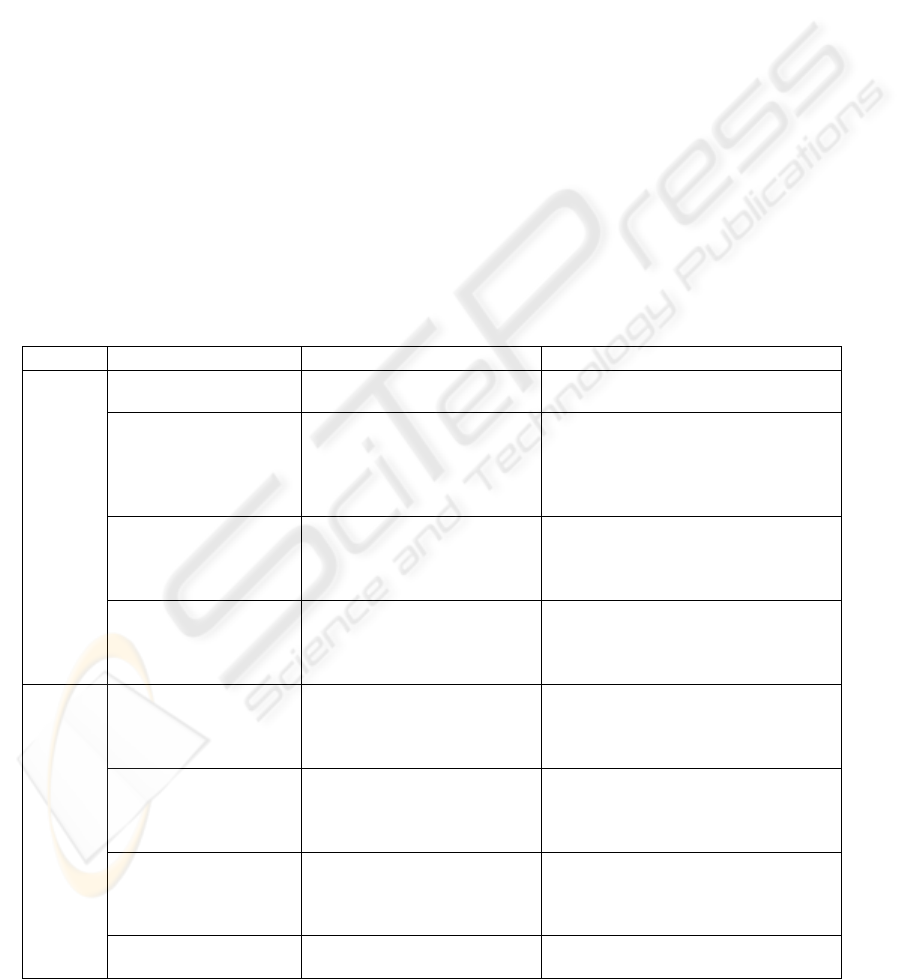

Table 1: Technological Critical Success Factor for ITO.

CSF

Reference

models

CSF

Reference

models

1. Define services from a modular

perspective

a - b - c - e 12. Consider corporate regulations b

2. Agree on the transfer of initial

resources

b 13. Consider governmental regulations a - c

3. Agree on the ownership of new

resources

b

14. Consider personnel resources

planning

b - e

4. Define a service evaluation structure a - b - c - d - e

15. Establish exclusivity agreements for

key areas

b

5. Define a predictable cost structure b - c

16. Manage risks and assign

responsibilities

b - d

6. Coordinate and standardize tasks

integration

c - e 17. Consider potential service changes a - b - d - e

7. Invest in technology innovations and

planning

c - d - e

18. Define contract termination

strategies

b

8. Maintain ownership and internal

capabilities

c - e 19. Accelerate services life cycles c

9. Consider licenses restrictions b

20. Take into account cultural

compatibility

a - e

10. Invest in value-added ecosystems

(integration of services offered from

different providers)

c

21. Dig deep into client-provider

relations

c

11. Establish multilateral agreements

with the right providers

a - b

22. Learn from the experience of allies

organizations

d

(a) College of Business University of Nevada (Dhillon, 2000), (b) Lovells International Law Firm (2006), (c) Cisco Systems Inc.

Strategic Out-Tasking Model (Brownell et al., 2006), (d) TBI ITO Governance Model (Bays, 2006) and (e) Center for Digital

Government & IBM (Robinett et al., 2006).

median established for the same type of project,

providing an overview of the project good/bad

performance to the extent it is below or above the

respective average values.

Table 2: Application of the GQM approach to CSF 1

“Define services from a modular perspective”.

Goal

Modularize the SOW definition of the

SW development service tasks from the

perspective of the SW development

project leader.

Question Q1

Does SOW include specification of

the customer’s needs?

Metrics M1

0: Not specified (0%)

1: Vague (25%)

2: Slightly specified (50%)

3: Well-specified (75%)

4: Detailed (100%)

Question Q2

Does SOW define the use of

development standards?

Metrics M2 0: No 1: Yes

Table 2 shows an example of the application of

the GQM model to CSF 1 “Define services from a

modular perspective” for software development

technology. Questions, metrics and corresponding

measuring scales are defined therein.

In short, the ITO project model based on

technology CSFs consists of 22 CSFs, including 400

questions and 400 metrics. Once proposed, the

model was evaluated.

5 MODEL EVALUATION

The model proposed was evaluated using the method

of Feature Analysis Case Study, which consists of

evaluation of a model once it is applied to a real

software project (Kitchenham and Jones, 1997).

Such method comprises two large processes, namely

Feature Analysis and Analysis Application to a Case

Study.

In this regard, it was required to establish a group

of features to measure questions associated to each

CSF and metrics assigned to each question. Then,

evaluators must decide whether metrics comply with

such features, as shown in Table 3, divided into

General and Specific Features; the former evaluate

the model at a macro level, and the latter evaluate

the model metrics. Additionally, the level of feature

acceptance was established at 75%. This percentage

was determined through consensus of the evaluators

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

178

and researchers, by also considering it as a common

practice for most quality models.

As for actors involved in the evaluation process,

their roles and responsibilities are detailed in

Kitchenham and Jones (1997): the sponsor is

Research Laboratory in Information Systems (LISI

by its abbreviations in Spanish); the article’s authors

were the evaluators; the model users were the

organization’s users who took part in the IT project

evaluation; and the model evaluators were the

organizations’ analysts/developers, leaders and

users, who answered the questionnaires.

For the purpose of analyzing the features (See

Table 3) an IT project was required. Therefore, a

software development project called SUAF (Unique

Anti-fraud System) was selected, which provides a

software solution for prevention and reduction of

bank frauds, capable of monitoring bank transactions

in real time and detecting irregular consumption

patterns. The client company is a medium-size

manufacturer, and the provider is a small-size

company. Users in the client company involved in

the SUAF project development evaluated the

project. These users answered the CSF questions

corresponding to the role they were assigned for

project development. This showed how each of the

model’s CSFs was applied to the project selected,

and translated into the project percentage of success.

Simultaneously, a set of questionnaires were

prepared to evaluate the ITO model based on

Technology CSFs against General and Specific

Features presented in Table 4. This in order to prove

the pertinence, completeness, adequacy and

precision of CSFs, as well as the pertinence,

feasibility, in-depth level and scale of the metrics.

These questionnaires were addressed to the

aforementioned model evaluators, who were also the

users in charge of evaluating the project.

Given that the project selected was included in

the ITO type defined as Outsourcing of Software

Development, only CSFs identified for this

classification were applied. Consequently, the

analysis of General and Specific Features is based

on the acceptance of these CSFs.

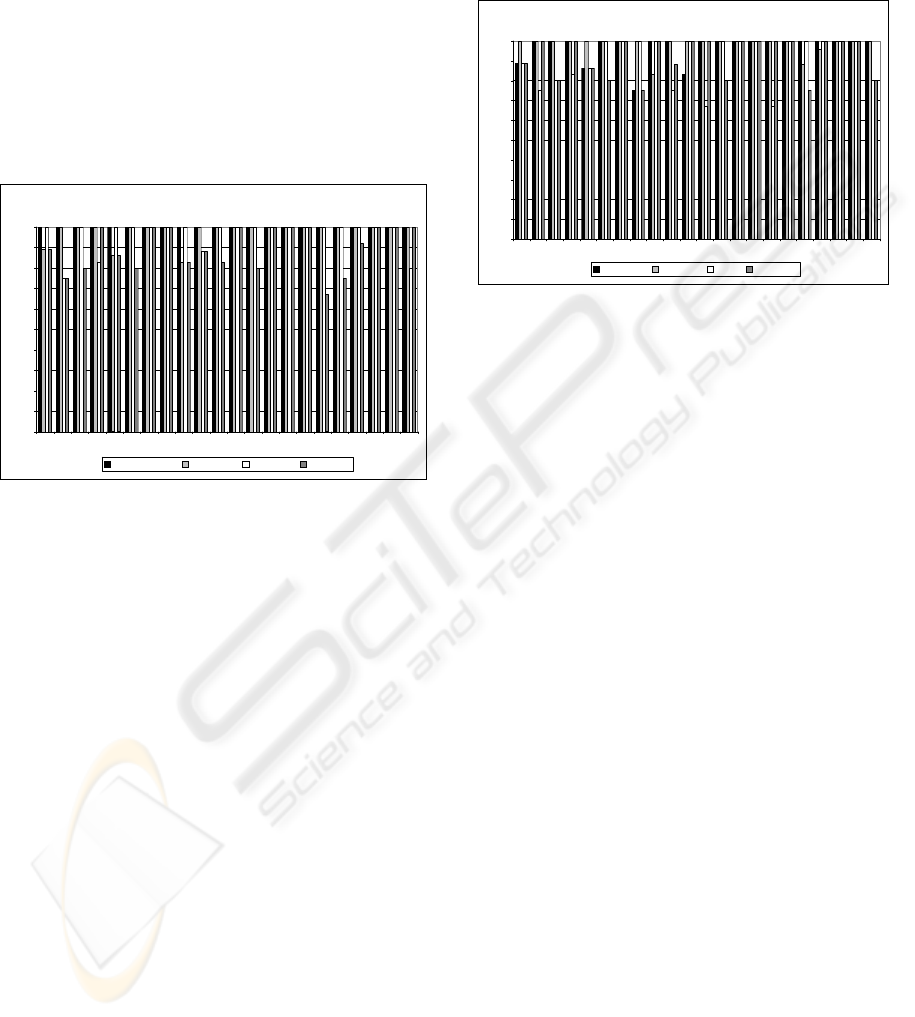

Table 3: General and Specific Features (Sosa, 2005).

Type Name Description Scale

General

Pertinence of question

The question is pertinent or

not in the context of CSF

1: The question is pertinent.

0: The question isn’t pertinent.

Completeness of CSFs

The questions give full

coverage to all CSFs.

1: CSF is complete in terms of the

questions used.

0: According to the context there are

new questions that should be

considered and incorporated.

Adequacy with the

context

The quality specification of

the question is adequate in the

context of the assessment

1: The question is adequate to the

context of the assessment.

0: The question isn’t adequate to the

context of the assessment.

Precision of quality

specified by the

question

The quality specified in the

question is precise.

1: The quality level specified is

precise.

0: The quality level specified isn’t

precise.

Specific

Pertinence of metric

The metric is pertinent for

measuring whether or not

there is the question to which

it belongs

1: The metric is pertinent.

0: The metric isn’t pertinent.

Feasibility of metric

it is feasible to measure the

question on the proposed

metric in the context of the

assessment

1: The metric is feasible.

0: The metric isn’t feasible.

In-depth level of metric

The metric has the level of

depth adequate to get an

relevant outcome

1: The metric has the level of depth

adequate.

0: The metric requires a higher level of

depth.

Scale of metric

The proposed scale is

adequate for measuring metric

1: The scale is adequate.

0: The scale isn’t adequate.

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS TO EVALUATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OUTSOURCING PROJECTS

179

Figure 1 shows the result of the analysis for the

General Features of the CSFs included in the model

proposed. A 100% completeness was observed for

all CSFs included in the model. Likewise, through

detailed observation, we noted an average pertinence

of 98% and 97% adequacy. The model’s most

deficient performance lies in precision, with an

average level of 90%, though a high level of

acceptance is maintained. Nevertheless, we can

observe a drop in certain metrics’ precision, as in

CSFs 17 (consider potential service changes) and 18

(Define contract termination strategies) with 67%

and 75% of acceptance, respectively.

Evaluation results of General Features

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10111213141516171819202122

CSF

Acceptance percentage

Completeness Pertinence Adequacy Precision

Figure 1: Evaluation Results of General Features.

Lastly, Figure 2 shows the evaluation of the

model Specific Features. In this respect, pertinence

of features shows a slight decrease when compared

to General Features with 97%; whereas feasibility

reached 99%. Depth accounts for the lowest levels

with an average 91%, which also remains

acceptable. However, what came to our attention

were the relatively low level of depth of CSF 12

(Consider corporate regulations) and 16 (Manage

risks and assign responsibilities), which reached

67%, thus not complying with the minimum

acceptance levels; therefore, such metric’s depth

should be improved. Adequacy of Specific Features

is lower than that obtained for General Features with

an average 92%, though all CSFs exceeded

minimum acceptance levels.

Based on the indicated above, some CSFs should

be improved, to a lower extent, as to pertinence

(CSF 1, 5, 8 and 11) and feasibility (CSF 9, 18 and

19); and to a higher extent, as to depth (CSF 1, 2, 3,

4, 5, 10, 12, 16 and 22) and suitability (CSF 1, 3, 5,

6, 8, 10, 13, 18, 22). The CSFs that need more

improvements were CSF 1, 5, 10, 18 and 22, which

showed weak behavior for two or more features.

These results, both for General and Specific

Features, show a higher level of acceptance of the

model proposed. The fact that all measurements are

above 67% and more than 80% are over 75% of

acceptance supports the model in general terms.

Evaluation results of Specific Features

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10111213141516171819202122

CSF

Acceptance percentage

Pertinence Feasibility Depth Adequacy

Figure 2: Evaluation Results of Specific Features.

6 DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Although the proposed model complies with

expected acceptance levels, after evaluating General

and Specific Features, it should be relevant to

improve, as ruled by future experiences, some of the

metrics proposed, so experts may more precision

rely on answering those questions that best represent

the reality. Likewise, we recommend making some

adjustments to the formulation of certain questions

so to better adequate them to the context in which

they are used and increase their general adequacy

level.

Though the proposed model only comprises

CSFs identified in the application of four relevant

types of ITOs, several CSFs may be applied to other

types of ITOs, and others may be included within

the model; the most relevant areas being BPO

(Business Process Outsourcing) and Help Desk due

to the large volume of existing documentation and

case studies found in the market. Other future

potential benefits may include studies on lineal

dependence/interdependence among the identified

CSFs, or between one CSF and global performance

of a certain project. Such dependencies might be

sorted by type of project in order to determine which

CSFs are of higher/lower relevance in accordance

with the type of projects, and to suggest model

modifications. Likewise, specifying the CSFs

already identified into more granular components

should be considered, including such detailed

aspects as differences involved in the application of

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

180

a certain product to cover the need for specific

technologies.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORKS

This article has proposed a Critical Success Factors

(CSF) Model for Information Technology

Outsourcing (ITO), which consists of 22 CSFs

classified in accordance with the technology aspect

encompassed by the ITO: data center, network,

software development and hardware support. In

addition, this model establishes a total of 400

metrics to measure CSFs.

The proposed model was evaluated using the

Features Analysis Case Study Method for

application of the model to a real case. The results of

this evaluation show a high level of acceptance for

the model proposed, specifically for the software

development area, as well as effectiveness of its

metrics, thus facilitating monitoring of the

percentage of success of an ITO Project. Besides,

the model provides guidelines addressed to the

parties involved in this service. It is necessary to

evaluate in future works the proposed model for the

data center, network and hardware support areas, as

well as to improve the CSFs for the General and

Specific Features above mentioned.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Engs. Nuñez and

Fernández for their valuable collaboration in the

culmination of this research.

REFERENCES

Austin, D., 2002. Understanding Critical Success Factor

Analysis. W. W. Grainger, Inc. W3C/WSAWG

Spring. Retrieved February, 2007, from:

www.w3.org/2002/ ws/arch/2/04/UCSFA.ppt.

Basili, V., 1992. Software modeling and measurement: the

goal/question/metric paradigm. Technical Report

CS-TR-2956. University of Maryland.

Bays, M., 2006. Best Governance Practices: Avoid

Surprises with a Thorough Governance Program. HRO

Today.

Brownell, B., Jegen, D. and Krishnamurthy, K., 2006.

Strategic Out-Tasking: A New Model for Outsourcing.

Cisco Systems, Inc., Internet Business Solutions

Group [IBSG]. Retrieved February, 2007, from

http://www.cisco.com/ web/about/ac79/docs/wp/Out-

Tasking_WP_FINAL_0309.pdf.

Casale, F., 2005. The Outsourcing Revolution. The

Outsourcing Institute. Retrieved November, 2006,

from: http://www.outsourcing.com/content.asp?page=

02v/articles/intelligence/OI_Index.pdf.

Dhillon, G., 2000. Outsourcing of IT service provision.

Issues, concerns and some case examples. Las Vegas,

EUA: University of Nevada, College of Business.

Fairchild, A., 2004. Information Technology Outsourcing

(ITO) Governance: An Examination of the

Outsourcing Management Maturity Model. Hawaii,

EUA: Tilburg University. Retrieved September, 2006

from: http://csdl2.computer.org/comp/proceedings/

hicss/2004/2056/08/205680232c.pdf

Lacity, M. and Willcocks, L., 2000. Survey of IT

Outsourcing Experiences in US and UK Organization

(Industry Trend or Event). In Journal of Global

Information Management, 2(8), 5-23. Retrieved

September, 2006, from: http://www.accessmy

library.com/coms2/summary_0286-28399756_ITM.

Lee, J., Huynh, M., Chi-Wai, R. and Pi, S., 2003. The

Evolution of Outsourcing Research: What is the Next

Issue. In 33rd Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences.

Lovells International Law Firm, 2006. IT Outsourcing.

Media Center Articles. Retrieved February, 2007,

from: http://www.lovells.com/Lovells/Publications/

Brochures/2443.htm?Download=True.

Robinett, C., Benton, S., Leight, M., Gamble, M. and

Drakeley, C., 2006. A Strategic Guide for Local

Government on: Outsourcing. U.S.A: Center for

Digital Government & IBM. Retrieved February,

2007, from http://www-935.ibm.com/services/au/igs/

pdf/au-ois-wp-strategic-guide-for-local-government-

on-outsourcing.pdf.

O'Brien, J. A., 2005. Introduction to Information Systems.

Nueva York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Pérez, M., Grimán, A., Mendoza, L. and Rojas T., 2004. A

Systemic Methodological Framework for IS Research,

In Proceedings of AMCIS-10, New York, New Cork.

Robinett, C., Benton, S., Leight, M., Gamble, M. and

Drakeley, C., 2006. A Strategic Guide for Local

Government on: Outsourcing. U.S.A: Center for

Digital Government & IBM. Retrieved February, 2007

from http://www-935.ibm.com/services/au/igs/pdf/au-

ois-wp-strategic-guide-for-local-government-on-

outsourcing.pdf

Sheehy, D., Baker, G., Chan, D., Cheung, A., Grunberg,

H., Henrickson, R., 2003. Information Technology

Outsourcing. Toronto, Canada: The Canadian Institute

of Chartered Accountants. Retrieved September, 2006,

from: http://www.cica.ca/multimedia/Download_Libra

ry/Research_Guidance/IT_Advisory_Committee/Engli

sh/eIToutsou rcing0204.pdf

Sosa, J., 2005. Human Perspective on Systemic Quality of

Information Systems. Working Masters in Systems

Engineering, LISI. Venezuela, Caracas: Simón Bolívar

University.

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS TO EVALUATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OUTSOURCING PROJECTS

181