WEBTIE: A FRAMEWORK FOR DELIVERING WEB BASED

TRAINING FOR SMES

Parveen K. Samra, Richard Gatward, Anne James

Coventry University, Faculty of Engineering and Computing, Priory Street, Coventry, West Midlands, U.K.

Virginia King

Centre for the Study of Higher Education (CSHE), Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, West Midlands, U.K.

Keywords: Training Framework, Online Learning, E-learning, SMES, Andragogy, Pedagogy, Constructivism.

Abstract: A yearlong pilot project undertaken in the UK set about delivering online training to 100 Small to Medium

sized Enterprises (SMES), which equated to 500 employees, all within Manufacturing. The ‘Cawskills

Project’ delivered online IT training directly to employees. The findings from the project have informed the

development of a generic but adaptive model for SMES to facilitate the need for training by considering the

operational demands, resources constraints and infrastructure. This paper presents a model, which brings

together principles of teaching and learning practices evident in classroom based education along with the

learning requirements of SMES and employees. The incorporation of online learning aims to deliver

training content, which is Just in Time (JIT) and proposes training events informed by SME’S strategic

direction.

1 INTRODUCTION

The need for training in every industry sector is

imperative to equip companies for a sustained

competitive advantage (Pedler, Boydell and

Burgoyne, 1998). In the light of globalisation, the

Manufacturing industry now acknowledges the need

for training (Khan, Bali & Wickramasinghe, 2007).

However, with a ‘myopic’ view of strategy,

operational demands and resource constraints, the

ability to take on board the level of training evident

in larger organisations puts Small to Medium sized

Enterprises (SMES) at a tremendous disadvantage

(Mazzarol, 2004:1). The UK Department of

Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR)

define SMES as “a business with fewer than 250

employees” (Berr, n.d). A SME needs to fulfil two

of the three conditions below to be defined as an

SME:

1. A turnover of not more than £22.8 million net;

2. A balance sheet total of not more than £11.4

million;

3. Not more than 250 employees.

The Manufacturing industry as a whole, accounts

for about 23.5% of employment in the UK. (Berr,

2005) The reduction in the workforce within

Manufacturing (Leitch, 2006; Flegel, 2006) has led

to the changing nature of work organisation in

particular influences of assembly line production.

Jones (2001) argues with JIT production, non-value

added activities are eliminated to allow the business

to address demands for “shorter cycle times, quicker

decision points and more rapid deployment of

services and solution” (2001:481). We can apply a

similar technique to delivering training in the light

of advances in ICT and the exploitation of the

Internet. JIT training should be available on

demand, be a more comprehensive training approach

associating training with work performance

requirements. Jones states that though JIT training

is delivered on an expedited basis, it does not mean

that the design process should be circumvented. To

help in the design process, Jacobs (2003) proposes a

model for job related training. On the Job Training

(OJT) has many advantages primarily the training is

tied with work practices and so has a positive impact

on individual’s motivation. OJT the process in

which, usually the, supervisor “…passes job

knowledge and skills to another person. (Jacobs,

2003:14). This form of unstructured and most often

204

K. Samra P., Gatward R., James A. and King V. (2008).

WEBTIE: A FRAMEWORK FOR DELIVERING WEB BASED TRAINING FOR SMES.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 204-209

DOI: 10.5220/0001691702040209

Copyright

c

SciTePress

informal training gave rise to Structured OJT (S-

OJT).

S-OJT is the planned process of “…developing

competence on units of work by having an

experienced employee train a novice employee”

(Jacobs, 2003:28). However, there is a need to link

training provisions to both training objectives and

business goals, thus we have relevance of training.

The training relates to the ability to perform specific

units of work with emphasis is on one-to-one

training (trainer and trainee relationship). It makes

use of a planned process rather than ad-hoc

explanations of work activities as with OJT and so

are regarded as a broad platform for enabling

workplace training. One consideration S-OJT fails

to make is the way in which the training should be

delivered. Despite the fact training should be work

situated it does not go further to explain how to

deliver the module content nor does it not consider

individual’s learning style. Despite the training

takes place in the organisational context, the content

is not associated with the organisation’s mission and

objectives. S-OJT does not go far enough to be

reactive to changing needs on a timely fashion.

Though, the need for training is recognised, it is not

supported by SMES current working practices,

culture, resources and training provision. They do

not have the time nor investment to generate

bespoke training programmes as mirrored in larger

organisation. As such, SMES look to initiatives

within the local area, which may cater for their

needs. SMES require a delivery mechanism, which

will not only be adaptive but also be responsive to

their needs.

2 WEBTIE

To address these issues we present a generic

adaptive model for SMES to deliver training within

the working day by utilising online learning

technology and underpin the training content with

Instructional design principles and learning theory.

The model encapsulates the specific learning needs

of employees and correlates them with the business

strategy. The proposed model will enable the

delivery of in house just in time training right to the

desktop. This design has been utilised to deliver

online training to manufacturing SMES in the

Coventry and Warwickshire region in the UK. The

informed design came about after the completion of

a yearlong training programme ‘Cawskills Project’,

with 100 SMES totalling 500 employees. The

training encapsulated European Computer Driving

Licence (ECDL) as the training content. The

development of the portal brought together four

main components: Learning content; Support forum;

Instructional Support and Technical Support.

Different people handled the management of these

four components but the goal was to bring them

together seamlessly. From the outset, we were

delivering a complete package, but from a design

point of view, we had a number of components from

different sources brought together until the portal.

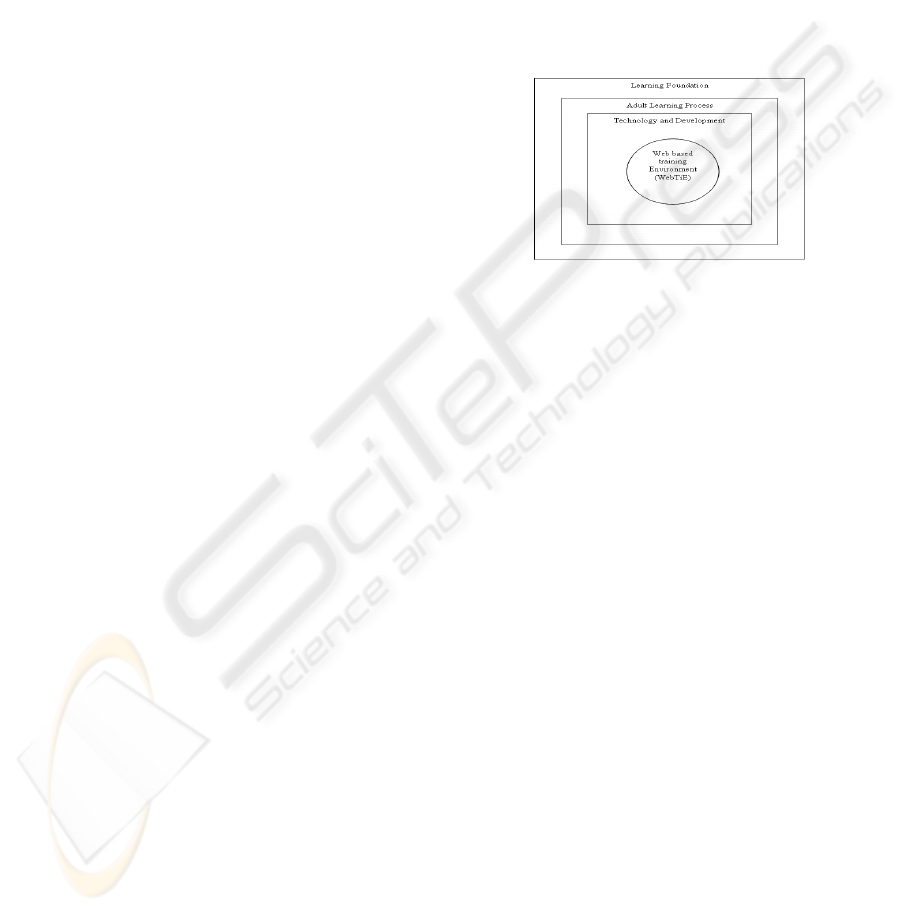

Figure 1 shows a Web Based Training

Environment (WebTiE) model used to deliver

training to SMES.

Figure 1: Training Development Model WebTiE.

The model has three distinct layers they are:

Learning Foundation; Adult Learning Process and

Technology and Development. Each layer is

concerned with the development process and

ultimately the incorporation of these layers will

bring about the development of WebTiE, a training

portal for SMES to undertake online training in-

house at the desk, perhaps at home or at other office

branches. The training will be specific to the

individual’s and SME’S learning needs. Over time

with changing needs the portal will adapt to new

arising requirements and challenges.

The Learning Foundation is an understanding of

the business, its mission, aim and objectives; its

focuses on change management and adapting culture

to allow for training. Above all, it is important to

understand the training requirements and their fit

with organisational requirements.

Adult Learning Process brings together

Andragogy, Behaviourism, Cognitive Theories,

Constructivism and Social learning to underpin

instructional design principles of the online training.

As previously stated, SMES operate at an

operational level and so have very limited time for

training, by optimising the instructional design we

are maximising the efficacy of the training event.

Technology and Development is both

constrained and enabled by the SMES’ ICT

infrastructure. The delivery mechanism must be in

place before any training is embarked. The

WEBTIE: A FRAMEWORK FOR DELIVERING WEB BASED TRAINING FOR SMES

205

development relates to the employer planning for the

training events. Each individual who is to take

training must be permitted time away from their job.

The employer and employee jointly need to plan

how this will happen.

3 HOW TO USE WEBTIE?

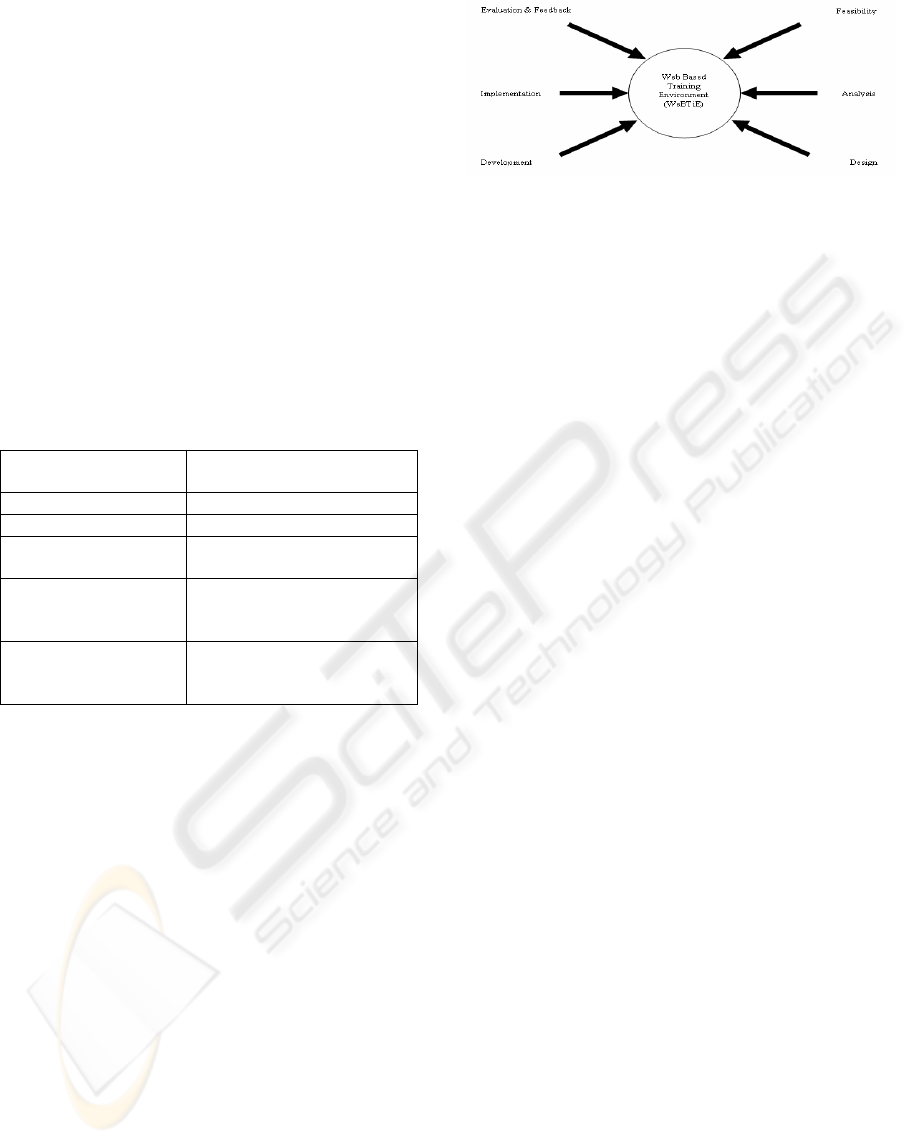

Figure 2 shows the main components to training

development, the design of which has been informed

by software engineering principles of information

systems design and development.

To illustrate how each phase above relates to Figure

1, Table 1 maps the stages of the above model

against the three main components defined in

Section 2.

Table 1: Mapping of WebTiE phases

Feasibility Learning Foundation

Technology & Development

Analysis Learning Foundation

Design Adult Learning Process

Development Adult Learning Process

Technology & Development

Implementation Technology & Development

Also, it is part of the core of

the model

Evaluation &

Feedback

This stage can bring about

iteration of the entire

developmental process.

3.1 Feasibility

Phase 1 of the training programme model seeks to

establish a platform upon which training programmes

will be developed. It is a process, which seeks to

implement change in the organisation’s culture to

bring about a ‘Learning organisation’. This stage

requires commitment from the employer and

employees alike who without which the success of

the programme will not work (Hutchinson & Purcell,

2007) nor will there be the ownership of the system

(Pressman, 1982; Mullins 1999).

There are three key components to this phase:

¾ Culture change and commitment

¾ SME mission and external business impact

¾ Technology

We are seeking to build an infrastructure or

environment within which training can take place, by

addressing the changing culture in readiness for

training and determining the strategy of the business,

you are modelling the infrastructure.

Figure 2: Phases of WebTiE.

A number of issues need to be addressed prior to

the development of the training programme to

ensure employee's readiness:

1. Do I have the time and financial investment for

training? (Investment and time to enable

employees train)

2. Are my employees willing to undertake

training? (Change management and culture)

3. Would I (the employer) like my employees to

undertake training? (Employer led training)

4. Do I have the IT infrastructure to enable the

training? (IT Infrastructure)

It is important to acknowledge these issues as

they enable the employer to demonstrate the

business readiness for training.

3.2 Analysis

Once the SME has the appropriate infrastructure as

defined in section 3.1.2 the assessment of training

requirements can commence. The assessment

process seeks to determine the skills requirements of

employees within the context of their job. A

Training Needs Analysis (TNA) (Reid & Barrington,

1997) process would shed light on whether or not a

skills gap exists. Attention needs to be given to tools

used within the job and the extent of its use by the

employee. SMES need to ensure that technological

understanding of employees is proficient enough. All

training the employee undertakes needs to link with

the SMES’ aim and objectives. Therefore, a two-fold

assessment process needs to take place. Many

initiatives such as those by Business Link are able to

undertake TNAs, free. This is particularly beneficial

to the UK SME where time and resources are already

clear constraints.

3.2.1 Individual and Organisational

Learning Needs

Training Needs Analysis will help to determine the

training requirements of the organisation and

individual employees in relation to the job

requirements and business requirements. The

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

206

analysis of this will identify one of two things.

Firstly, individual training requirements and

secondly commonality training requirements

throughout the business. These requirements will

then need to be prioritised. To help in prioritisation

a useful technique to use is MOSCoW (Howard,

1997; Ash 2007). Its’ development is attributed to

Dynamic Systems Development Methodology

(DSDM), a management and control framework for

rapid application development. The most important

training requirements, the ‘Must have’ would be the

requirements for which training must be sought

immediately as these are fundamental to business

success. This process is carried out on a timely basis

and informed by previous training evaluation

activities. However, it is important to note that the

training requirements identified need to be linked to

the SME’s strategic direction. The second process

during this phase is to ensure that those people

selected for training have the appropriate access to

the training portal. This process will involve both

the employer and employee. By involving the

employee in such decision making you are

motivating the employee and giving them ownership

of the training process.

3.3 Design

As shown in Table 1, the design phase is part of the

Adult Learning Process. SMES are unlikely to have

the time and resources internally to develop tailored

content for employees, as may larger organisations.

The training content remains relatively static and so

the SME needs to consider Instructional Design

issues may vary. This phase brings together three

main components: Instructional Design;

Instructional Support and Event Learning Plan.

Once the training has been identified and the

infrastructure is in place can the employer seek the

training vendor. To determine a potential vendor we

need to ensure the training content fulfils the

individual learner’s requirements and organisational

mission. As previously mentioned there are

numerous online training programmes already

available but none, which can cater for the

individual SME. The aim is to build a suite of

training programmes, the portal will become a

portfolio of training requirements, which caters for

SMES’ learning requirements. Up until now, the

model has addressed internal factors of the business,

which hinders training, we now look externally for

learning content that fulfils our learning needs.

Previously SMES gave little focus to what training

was required and how this will benefit the business.

We now have a clear understand of both and

therefore a clear focus on what we need from the

training vendor.

Once the potential training vendor has been

identified, the SME will need to work closely to

bespoke the training to their requirements. This is

not simply a process of tailoring the interface but

moreover tailoring the delivery process.

3.3.1 Instructional Design

The principle aim is to deliver a training experience,

which has been optimised by adult learning theories.

Pedagogic principles evident in classroom-based

teaching tend not to consider previous knowledge

and experience of trainees. Andragogy (Knowles,

1990) relating to how adults learn can be embedded

in training programmes. Andragogic principles take

the matter of previous experience and knowledge as

one of its core considerations. This will help to

ensure the delivery of training is of a high quality

through optimal learning but within the parameters

business.

Below is a list that provides generic instructional

design principles to be used in the development of

the training content. The list incorporates theories

relating to Constructivism and Usability. It also

considers the development of a learning organisation

and a Community of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998).

Use of S-OJT to allow for JIT training.

Customisation and Modularisation of learning

content (Dabbagh, 2007; Miller, 1956;).

Clear links between modules and objectives and

linking of modular objectives to business mission.

Consideration of previous knowledge and

experience in defining training programmes for

employees.

Promotion of deep learning through linking of

training with work practices.

Option for restarting the training programme at

varied user defined points.

Consistency within the portal. Eliminating of

unnecessary icons, features or graphics keeping the

interface simple and easy to follow by removing

unnecessary functionality.

Content a combination of textual and graphical

with sound controlled by the trainee.

Minimisation of scrolling enables the mimicking

of reading of a book.

Hyperlinking to make connections between

sources, thus supporting understanding of key

concepts and the cross fertilisation of ideas.

WEBTIE: A FRAMEWORK FOR DELIVERING WEB BASED TRAINING FOR SMES

207

A mechanism of feedback is required, which is

individualistic and constructive hence promoting

motivation.

A process of assessment needs to be embedded to

allow the trainee and trainer to ascertain the

degree of knowledge acquisition balanced by the

learning content and time constraints of trainees.

Need for certification or qualifications marking

the end of training events (Young, 2002).

These suggestive guidelines are not designed to

change the learning content but to tailor it to the

needs of the SMES learning style and optimisation

of learning.

3.3.2 Instructional Support

A learning support system in the form of emails,

discussion forum and face-to-face support with the

trainer is required. Just as in the classroom

environment, trainees seek support from one another

to problem solve; the same opportunity needs to be

present online. The use of CoPs encourages the

exchange of ideas and problem solving to help in the

application of training to work based practices

(Wenger 1998).

The application of Hybrid delivery will help

learners with limited experience in such training

Phased classes scheduled for the trainees provide the

opportunity to meet with the trainer and other

trainees at the SME location to receive some

remedial help. One vital face-to-face class that must

take place would be the first initial contact with the

trainer. As we found in our fieldwork the

introductory training class was both well received

with trainees and helped to motivate them. It also

gave the opportunity to alleviate early teething

problems with logins and general use of the training

portal.

The training vendor is required to provide

technical support, a surety to the employer who may

not be technically proficient themselves that help is

at hand.

3.3.3 Event Learning Plan

A training plan needs to be produced to define when

an individual can take time to train. This helps both

the employer focus on releasing an employee for

training and for the employee to understand that the

employer has invested in them to take time away for

training and that this is their time for that. The

Learning Event plan can be as formal as the SME

needs it to be to manage training and evaluation

Clearly, there are benefits to recoup if the document

is formalised, as it will clearly set out who is doing

training, when and their progress.

3.4 Development

Phase four, the development of the training

environment needs to be informed by the SME. As

the trainer vendor develops this, they need to

collaborate with the SME. Unlike off the shelf

training SMES should seek to having bespoke

training. For this reason, they are stakeholders in a

programme development. The software should be

tested in collaboration with end users. The testing

and involvement process will give ownership to the

trainees and preparedness of the impending training.

3.5 Implementation

Phase five, requires the collaboration of all

stakeholders. As with any software development and

implementation, this process requires delicate

handling. Both the training vendor and the SME

should agree the implementation technique.

However, whichever method is used to implement

the programme appropriate technical support must

be to hand to eliminate both bugs and to address

finalised tailoring requirements.

3.6 Evaluation & Feedback

The employer and employee alike who undertake

training need to evaluate the progress of training and

whether further training is required. The process

need not be a formal method of assessment. We

propose a phased process paralleled with the

completion of new modules. This process can be

employee instigated who will undoubtedly identify

areas of improvement in their working practices and

bringing this to the attention of the employer will aid

on the way to job enrichment. The evaluation

process will adapt the Kirkpatrick’s model (1996)

aiming to measure reaction, learning, behaviour and

finally the results ascertaining the effects on the

business resulting from the trainee's performance.

To take the benefits of the training into the business

you must look to changing processes. This process

can be repeated to see whether the change has been

effective and beneficial or not.

Subsequently, we can return to the second layer

of WebTiE, where we once again focus on learning

needs (TNAs) if additional requirements identified

then we can repeat the process of training until a

level of satisfaction has been reached.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

208

4 CONCLUSIONS

The proposed generic framework aims to fulfil the

learning and organisational learning requirements of

SMES. Competitiveness and economical factors

which stand in their path must be overcome by

driving flexible JIT training for better productivity

and operational effectiveness in the face of

globalisation. It is not simply a question of

acquiring a set of technical skills, but rather a

process of reflection and review of current practices

that are informed by better ways of working. The

creation of knowledge need to be a collective

activity, where employers and employees alike

exchange ideas, share problems and solutions

(Wyer, Mason, Theodorakopoulas, 2000).

The importance of training is acknowledged by

SMES, however, the provision available is much

criticised as lacking quality and relevance. A

training program with a sound underpinning will

optimise the training experience. Swanson argues

that on the job training and learning is vital to

businesses and therefore “t

raining is about creating

expertise, not simply pouring knowledge into people”

(Zemke, 2002: 87). Businesses who report

difficulties in recruitment and skills gap need to start

to look inward in up-skilling rather than outward to

recruitment. Investment in training employees does

have a return on investment in the shape of better

productivity, staff retention, and motivation (Leitch

2006). The continuing down turn in manufacturing

will remain will remain until UK SMES are in a

position to rival the international manufacturing

industry once more.

REFERENCES

Ash, S. (2007) MoSCow Prioritisation. DSDM

Consortium [online]

<www.dsdm.org/knowledgebase/download/165/mosc

ow_prioritisation_briefing_paper.doc> [Nov 2007]

Berr, (n.d) Better Business Framework, [online]

<http://www.dti.gov.uk/bbf/small-business/research-

and-statistics/statistics/page38573.html> [Dec 2007]

Berr, (2005) Enterprise Directorate: Small and Medium

Enterprise Statistics for the UK and Regions [online]

<http://stats.berr.gov.uk/ed/sme/SMEStats2005.xls>

[Dec 2007]

Flegel, H (2006) Manufacture Strategic Research Agenda,

Assuring the future of Manufacturing in Europe.

Manufacture Platform High Level Group, European

Commission

Howard, A (1997) A new RAD-based approach to

commercial information systems development: the

dynamic system development method. Industrial

Management & Data Systems. vol 97, No 5, p175-177

Hutchinson, S. & Purcell, J. (2007) Learning and the line:

The role of line managers in training, learning and

development. London: Chartered Institute Of

Personnel and Development

Jacobs, R.L (2003) Structured on-the-job training.

Unleashing employee expertise in the workplace. (2

nd

Edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc.

Jones, M.J (2001) Just-in-Time Training Advances in

Developing. Human Resources. November vol 3, No

4, p480-487

Khan, Z., Bali, R. & Wickramasinghe, N. (2007)

Identifying the need for world class manufacturing and

best practice for SMES in the UK. International

Journal for Management and Enterprise Development,

vol 4. No. 4, p428-440

Kirkpatrick, D.L., (1996) Evaluating Training Programs:

The four levels, Berrett-Koehler,

Knowles, M., (1990) The adult learner a neglected species

Gulf publishing

Leitch, L.S. (2006) Leitch Review of Skills. Prosperity for

all in the global economy – world class skills. Final

Report. The Stationary Office. [online] <hm-

treasury.gov.uk/leitch> [May 2007]

Mazzarol, T. (2004) Strategic management of small firms:

a proposed framework for entrepreneurial ventures

paper presented at the 17

th

Annual SEAANZ

conference, Brisbane, September In Walker et al

(2007) Small business owners: too busy to train? In

Journal of Small business and Enterprise

Development. vol 14, No2,p294-306

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or

minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing

information. Psychological Review, vol 63, p81-97

Mullins, L.J. (1999) Management and Organisational

Behaviour 5

th

Ed. Financial Times Prentice Hall

Pedler, M., Boydell, T. & Burgoyne, J. (1998) Learning

Company Project: A report on Work Undertaken

October 1987 to April 1988 Sheffield, Training

Agency

Pressman, R. (1982) Software Engineering A

practitioner’s approach 4

th

Edition McGraw Hill

Reid, M., & Barrington, H., (1997) Training Interventions

Managing Employee Development, 5

th

Edition,

Institute Of Personnel and Development.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning,

Meaning and Identity. Cambridge University Press

Wyer, P. Mason, J., & Theodorakopoulas, N. (2000) Small

business development and the “learning organisation”

International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour &

Research. vol 6, 4, p239-259

Young, M (2002) Contrasting approaches to the role of

qualifications in promotion of lifelong learning. In

Working to Learn (Ed) Evans, K., Hodkinson, P. &

Unwin, L. Kogan Page.

Zemke, R. (2002) Who needs Learning Theory Anyway?

Training - New York. vol 39, No 9, p86-91.

WEBTIE: A FRAMEWORK FOR DELIVERING WEB BASED TRAINING FOR SMES

209