A Preliminary Study on Inducing Lexical Concreteness

from Dictionary Definitions

Oi Yee Kwong

Department of Chinese, Translation and Linguistics and Language Information Sciences

Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Abstract. While the distinction between concrete words and abstract words ap-

pears to be inherent, the measure of lexical concreteness relying on human rat-

ings is more intuitive than objective. In this study, we aim at extending the

concreteness distinction from the lexical level to the sense level, and inducing a

numerical index of concreteness for individual senses and words from dictio-

nary definitions. The high overall agreement between human ratings and defi-

nition-induced ratings is encouraging for us to further simulate the distinction

from more language resources. Such a simulated index for concreteness is be-

lieved to inform not only lexicography but also natural language processing

tasks like automatic word sense disambiguation.

1 Introduction

There is apparently an inherent distinction between concrete concepts and abstract

concepts in our perception of the world. This distinction persists among the words

with which the concepts are lexicalised. Psychologists have shown, from lexical

decision and naming tasks amongst others, that abstract words are harder to under-

stand than concrete words (e.g. [1, 4]). There is also substantial evidence from child-

ren’s spoken and reading vocabulary that abstract words are acquired later than con-

crete words (e.g. [12]). This distinction of concreteness and abstractness is very like-

ly reflecting differential underlying mechanisms in the representation, development,

and processing of word meanings in the mental lexicon.

The concreteness factor has often been discussed only at the lexical level but sel-

dom at the sense level. The relation between concreteness and polysemy is rarely

addressed in the literature. Given the psychological validity of the concreteness dis-

tinction, however, it must have in turn affected the way word meanings are accessed

in various comprehension and production tasks. Hence, the inclusion of the con-

creteness information in computational lexicons, by analogy, should also benefit

natural language processing tasks like automatic word sense disambiguation. It

would also allow us to study polysemy and sense similarity in a more comprehensive

and cognitively plausible way.

Although concreteness is taken to be a fundamental semantic distinction among

words, somehow there is no concrete definition for it. The general idea is that con-

creteness or abstractness is a matter of degree, and is often measured by means of

Yee Kwong O. (2008).

A Preliminary Study on Inducing Lexical Concreteness from Dictionary Definitions.

In Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Natural Language Processing and Cognitive Science, pages 84-93

DOI: 10.5220/0001738400840093

Copyright

c

SciTePress

human ratings for a sample of words. Such measures are therefore more intuitive

than objective. It would certainly help if we could automatically derive from one or

more existing language resources a numerical index for the degree of concreteness,

which reliably simulates human judgements. To this end, we attempt to make use of

dictionary definitions and study the correlation between their styles and the concrete-

ness of the concepts they are defining.

Thus in this study, we aim at extending the distinction between concreteness and

abstractness from the lexical level to the sense level, and inducing an index of con-

creteness for individual senses and words from dictionary definitions.

In Section 2, we further set out the background of this study. In Section 3, we out-

line the importance of dictionary definitions in human language acquisition and the

relation between definition styles and the level of concreteness, with our preliminary

categorisation of dictionary definitions by surface syntactic forms. In Section 4, we

describe the materials and method used in this study. Results are presented and eva-

luated in Section 5. They are further analysed and discussed with future directions in

Section 6, before we conclude in Section 7. In this paper we use “lexical concrete-

ness” and “sense concreteness” as a generic term for the degree of concreteness, from

highly abstract to highly concrete, of words and senses respectively.

2 Background

Many psycholinguistic studies on lexical processing confirmed that abstract words are

harder to understand than concrete ones. For instance, concrete words are often

found to lead to shorter reaction times than abstract words in lexical decision tasks

(e.g. [1,4]). Such concreteness effect is concurrently under the influence of various

lexical, semantic, and even personal factors, including word frequency, imageability,

experiential familiarity, and context availability [2,4,9]. Different theories have been

put forward to account for the concreteness effect (see [9] for a summary).

Understanding the concreteness effect in terms of the representation, acquisition,

and processing of words of various degrees of concreteness is thus essential to our

understanding of the nature of word meaning. The observed difference between the

two kinds of words also implies a somewhat different mechanism by which they are

stored, represented, connected, and processed in the mental lexicon. While there

were studies investigating the relationship between lexical access and polysemy (e.g.

[10]), few have addressed the relation between concreteness and polysemy. Analysis

on word association responses, for instance, has suggested that tangible concepts

seem to be more easily activated than abstract concepts; and in the case of polysemy,

tangible senses appear to be more accessible than abstract senses [6]. However, con-

creteness is often discussed only at the lexical level but seldom at the sense level,

leaving many questions unanswered to date: Is the perceived lexical concreteness

associated with the concreteness of the dominant sense of a word? Given that context

availability might affect the processing of concrete and abstract words, how does this

effect populate to the individual senses of a word, which is likely to have an impact

on the information susceptibility [5] and hence information demand in automatic

85

word sense disambiguation? We must therefore also look into concreteness at the

sense level.

Moreover, concreteness is often measured in terms of human ratings on an ordinal

scale from highly abstract to highly concrete. Although it is reliable to a certain ex-

tent, it is nevertheless more intuitive than objective, and can hardly be scaled up to be

directly employed or tested in natural language processing tasks such as word sense

disambiguation. In fact, the latter would be feasible only if we could automatically

induce an objective measure of concreteness which is comparable to human judge-

ments. Lexical data reflecting human lexical processing is possibly available from

various resources, including dictionary definitions, word association norms, lexical

and knowledge bases, as well as corpus data from authentic texts. Given the compli-

cated interaction of the various factors in determining lexical concreteness, in the

current study we aim at investigating the feasibility of simulating human judgements

on concreteness from dictionary definitions.

The current study is therefore motivated, on the one hand, by the need to extend

the discussion of concreteness from the lexical level to the sense level; and on the

other hand, by the goal to objectify and quantify the concept of lexical concreteness

for natural language processing. We start with dictionary definitions, assuming that

words of different degrees of concreteness are most suitably defined in different

styles. Hence, we analyse and categorise dictionary definitions to study the relation-

ship between definition styles and the perceived lexical concreteness, and induce a

numerical index from definition categories to simulate human judgements on con-

creteness.

3 Dictionary Definitions and Lexical Concreteness

According to McKeown [7], “a definition can be seen as an attempt to capture the

essence of a word’s meaning by summarizing all of its applications and possible ap-

plications”. Very often, part of our acquisition of word meanings comes from dictio-

nary lookup, in addition to personal experience and contact with family, peers, school,

and mass media, which might all contribute to the word frequency and familiarity

effects as discussed in the literature.

Although nouns are expected to be relatively easy to define, as compared to other

parts-of-speech, various defining styles are observed [3]. A common type is by means

of genus (superordinate concept) and differentiae (distinctive features). For words

which are not easy to be defined by a genus term, the definition is often composed

with a synonym, a collection of synonyms, or a synonymous phrase. Another kind of

definitions is by means of prototype, which is similar to the genus and differentiae

type but in addition specifying what is typical of a referent with words like “typical-

ly” or “usually”. For others, where a referent is unlikely to be available, lexicograph-

ers will capture their meanings in a dictionary by explaining their usage in real text.

It is also commonly realised that tangible objects and physical actions are more easily

defined in dictionaries, while abstract concepts and other aspects of meaning includ-

ing connotation, sense relations, and collocations are less readily and often only par-

tially covered by the definitions.

86

In this study, we assume that the concreteness of a concept will make a difference

on the most appropriate defining style. Specifically it will be more difficult to define

abstract concepts by means of genus and differentiae, and prototype, and they are

more likely to be defined by synonyms and other means. We therefore analysed

dictionary definitions and distinguished them into seven categories based on their

surface syntactic forms, corresponding to a 7-point scale (7=highly concrete,

1=highly abstract) which is assumed to correlate with various levels on the concrete-

abstract continuum from human judgements. The definitions used in this study were

obtained from WordNet 3.0 [11]. The seven categories are listed and explained in

Table 1.

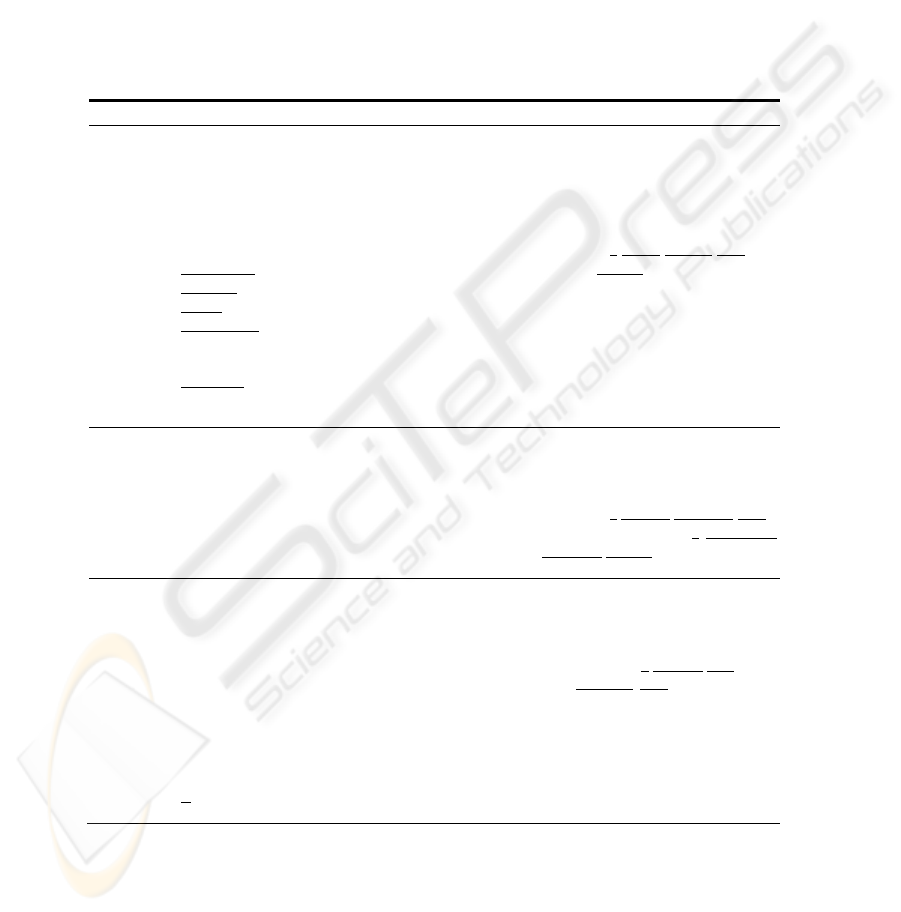

Table 1. Categorisation of Dictionary Definition Styles.

Category Patterns Explanation and Examples

7

Genus + Differentiae + Prototype

Surface pattern:

Determiner + (Modifier) + Genus + Differentiae +

Prototype

where:

Determiner

= {a, the, all of the, all the, any}

Modifier

= 0 to N words modifying the genus

Genus

= a countable noun

Differentiae

= phrase/clause introduced by {that,

where, who, which, for, to, of, with} or a relative

clause omitting ‘that’

Prototype

= phrase/clause introduced by {usually,

typically, especially, mainly, often}

Concrete concepts are usually de-

fined in terms of genus and differen-

tiae. High imageability is assumed

if a prototype could also be de-

scribed.

e.g. car – a

motor vehicle with four

wheels; usually

propelled by an in-

ternal combustion engine

6

Genus + Differentiae / Prototype

Surface pattern:

As above with either Differentiae or Prototype

b

ut

not both present

Assume slightly less concrete if no

distinctive feature or prototype is

captured.

e.g. bag – a

flexible container with a

single opening; cup – a

small open

container

usually used for drinking

5

Special Genus + Differentiae / Prototype

Modified Genus only

Someone + Differentiae / Prototype

Surface pattern:

1. a + (Modifier) + X of + Genus + Differen-

tiae/Prototype

2. Determiner + (Modifier) + Genus

3. someone + Differentiae/Prototype

where:

X

= {kind, type}

A less detailed description of the

concepts but at least a person or

some known membership

e.g. husband – a

married man; offic-

er - someone

who is appointed or

elected to an office and who holds a

position of trust

87

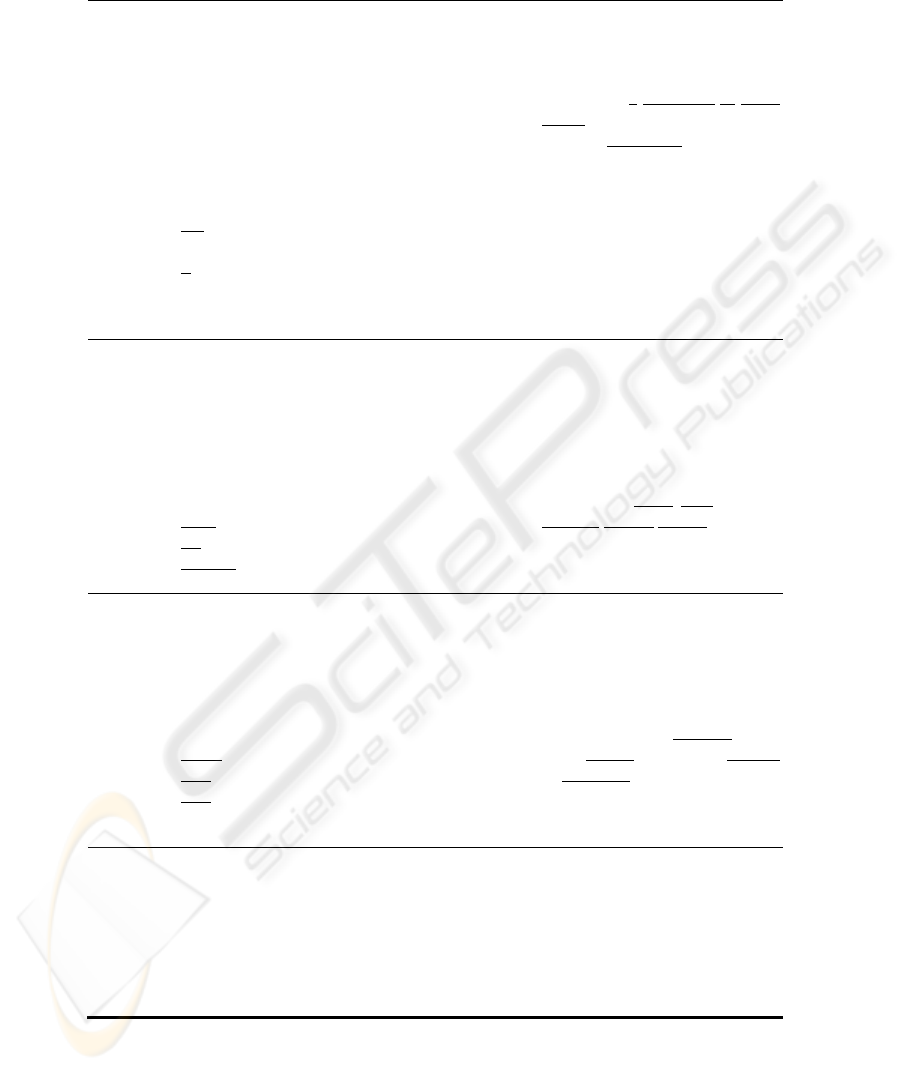

Table 1. Categorisation of Dictionary Definition Styles (cont.).

4

Empty Kernel + Differentiae / Prototype

Special Genus only

Surface pattern:

1. a + (Modifier) + X of + Genus

2. EK + Differentiae/Prototype

3. a + (Modifier) + Y of + Genus + Differen-

tiae/Prototype

where:

EK

= {somewhere, something, anything, a

thing, an object}

Y

= {set, branch, instance, quantity, amount,

number, form, group, part, portion, collec-

tion, item, series, area}

Empty kernels or underspecified

objects, but still describable in

terms of distinctive features

e.g. body – a

collection of parti-

culars considered as a system;

mercy – something

for which to

be thankful

3

Synonyms or synonymous phrases

Surface pattern:

1. SDet + (Modifier) + SX of + SGenus

2. (SDet) + (Modifier) + SGenus + (Differen-

tiae/Prototype)

where:

SDet

= {a, the, your}

SX

= {state, part, instance}

SGenus

= a mass noun

Unlike tangible objects and

p

hysical actions, more abstract

concepts are less feasibly and

less likely to be defined in terms

of countable nouns as genus and

differentiae.

e.g. hour – clock

time; glory –

brilliant

radiant beauty

2

Noun phrases in specific forms involving

only mass nouns

Surface pattern:

MDet + SN1 + of/to + (Modifier) + SN2

where:

MDet

= {your, the}

SN1

= a mass noun

SN2

= a mass noun / a countable noun in

plural form / a gerund

Mass nouns are often more ab-

stract, and the abstraction often

doubles up in patterns in this

category involving two mass

nouns.

e.g. hatred – the emotion

of in-

tense dislike

; idea – the content

of cognition

1

All others, including explanation of usage

Presumably highly abstract con-

cepts need to be explained more

verbosely in other forms.

e.g. baby - sometimes used as a

term of address for attractive

young women

88

4 The Current Study

In this section, we outline the procedures in selecting word samples and comparing

human and definition-induced ratings on concreteness.

4.1 Materials

The word samples used in the current study were selected from the lexical access

study by Kroll and Merves [4], who used a set of 200 concrete and abstract word

samples matched on frequency and word length. These words were rated by human

subjects for concreteness on a 7-point scale. For the current preliminary study, we

selected samples from their list with frequency greater than 20. One reason for this

selection is that we were asking non-native speakers of English (that is, local under-

graduate students from Hong Kong) to rate the concreteness of the words and their

senses. Thus we wanted to start with the more frequent items which are more likely

to be familiar to the raters.

A total of 100 word samples were thus selected, including 50 words categorised as

“concrete” and 50 as “abstract” according to [4].

Sense definitions were collected for these words from WordNet 3.0 [11]. Word-

Net organises word senses in the form of synsets (i.e. sets of synonyms) with rela-

tional pointers linking among different synsets to form some sort of a semantic hie-

rarchy. Each synset/sense has a gloss which resembles definitions provided in con-

ventional dictionaries. WordNet was first created for psycholinguistic studies of the

mental lexicon but turned out to be an electronic resource widely used by computa-

tional linguists.

The average number of senses per word for the concrete nouns is 4.36, and the

words have 1 to 17 senses. The average for abstract nouns is 3.44 senses per word,

and the words have 1 to 9 senses.

4.2 Method

Four human judges were asked to rate the words and senses in the sample on a 7-

point scale of concreteness, with 1 for highly abstract, and 7 for highly concrete.

Ratings were to be given to all words (ignoring individual senses) first, and then

independently to each sense. They were asked to do the rating according to their

intuition and subjective evaluation, although it was also suggested that imageability

could be used as one criterion in their judgement without precluding other relevant

factors. Two of the judges were undergraduate students and the other two were gra-

duates. All have studied linguistics before.

Each sense definition obtained was classified into one of the seven types of defini-

tions as discussed in Section 3 and exemplified in Table 1. The category assigned to

each sense definition was thus taken as a numerical indication of the concreteness of

the respective meaning on a 7-point scale.

The results were analysed and compared with respect to the following:

89

− agreement among the human judges at both the word level and sense level,

− agreement between the sense definition category and human ratings, and

− correlation of lexical concreteness rating between human and the definition catego-

ry of the first sense of a given word (DefOne), and between human and the aver-

age of definition category values from all senses of a given word (DefAll).

5 Results and Analysis

In the following we first present results on the human ratings and assess the degree of

agreement among different raters, and then compare human ratings with those in-

duced from definitions based on different combinations of senses.

5.1 Agreement among Human Raters

The Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance W was computed to assess the agreement

among the human raters. An overall W of 0.811 was found at the word level among

our four judges, suggesting that the raters in general agree with one another on posit-

ing the word samples on the lexical concreteness continuum, although the absolute

ratings they have assigned to individual samples might differ.

The correlation between the ratings obtained in Kroll and Merves’ study [4] and

the average rating on the words from our raters is very high. A high Spearman rank

correlation of 0.848 (significant at 0.01 level) was found. This reflects that despite

the different personal backgrounds of the raters in the two studies, there seem to be a

general consensus and intuitive feeling regarding concreteness distinction.

The mean ratings on concrete and abstract nouns from the two studies are shown in

Table 2 (columns K&M and Current). There is a significant difference on the mean

ratings between the two types of nouns, which further confirms the psychological

validity of the concrete-abstract distinction. It is apparent that raters in the current

study tend to be more “generous” on concrete items but more “conservative” on ab-

stract items. They are more ready to rate a concrete word as “highly concrete” than to

rate an abstract word as “highly abstract”, although it is difficult to control for what

should be regarded as “highly abstract” on the scale, as high and low imageability

may not mirror each other on the concreteness scale. Despite the difference in the

number of raters in the two studies, the overall distinction is similar. It could be a

subtle difference between native and non-native speakers of English which is reflect-

ed in the slight difference in an opposite direction for the two types of words.

Table 2. Comparison of Mean Ratings from Various Conditions.

K&M Current

DefOne DefAll

Concrete

5.92 6.19

5.98 5.69

Abstract

2.63 2.96

4.52 4.59

90

5.2 Reliability of Definition-Induced Ratings

With the definition category assigned to each sense definition, lexical concreteness

was induced from two conditions. One is to simply use the category value from the

first sense of a word, which is presumably the dominant or most frequent sense ac-

cording to WordNet ordering. We call this condition DefOne. The other is to take

the average of the category values from all senses of a word, and we call this condi-

tion DefAll. The mean ratings for concrete and abstract nouns obtained from these

two conditions are shown in Table 2 (columns DefOne and DefAll).

To assess the comparability of the lexical concreteness index simulated from dic-

tionary definitions, we test for the correlation and agreement between human ratings

and the definition-induced values. The corresponding values for the Spearman rank

correlation ρ and Kendall’s W are shown in Table 3. All values are statistically sig-

nificant.

Table 3. Correlation and Agreement between Human Ratings and Definition-Induced Ratings.

K&M

Current

ρ W

ρ W

DefOne

0.468 0.733

0.528 0.762

DefAll

0.430 0.715

0.494 0.747

Table 3 shows that the correlation (as shown by ρ) between human ratings and de-

finition-induced ratings is not particularly strong and linear, but the overall agreement

(as shown by W) is nevertheless quite high. It is apparently seen from Table 2 that

the simulation from definition categories works better on concrete nouns than abstract

nouns. There are two possible reasons. One is the various definition styles are not

exclusively found for the two types of words. In reality, abstract words might also be

defined in terms of genus and differentiae. This point will be further discussed in the

next section. Another possible reason is that abstract nouns might also contain con-

crete senses which might have an impact on the overall lexical concreteness, especial-

ly considering that abstract nouns are usually less polysemous than concrete nouns.

6 Discussions and Future Work

One important observation from the results is that although the correlation between

the numerical assignment on the concreteness scale from various rating sources is not

particularly strong, the overall agreement on the ranking has been high among human

judges as well as between human and definition-induced ratings. The 7-point con-

creteness scale is an ordinal measurement which might not be equidistant, and how

people perceive the distance between two points on the scale is unknown. As men-

tioned earlier, the perceived concreteness might be a result of the interaction of many

factors, including word frequency, familiarity, context availability, etc. It appears

that native speakers in [4] consistently gave a lower point than the non-native speak-

ers in our study to concepts related to people, e.g. father, friend, husband, lawyer,

consumer, etc. The noticeable difference on the ratings for the abstract nouns like

91

devil, spirit, method, glory, etc. might also reflect a cultural difference and thus per-

sonal familiarity and the availability of context. Even among the judges in the current

study, we observed contrastive ratings for words like town, field, carbon, pattern,

moral, humor, and theory. This suggests that personal experience and intuition might

play a more important role than other objective factors on the judgements for con-

creteness.

A potential limitation of our current categorisation of the dictionary definitions is

that abstract concepts might be defined by genus and differentiae more often than

expected. For instance, one meaning of “mercy” is “a disposition to be kind and for-

giving”, and one meaning of “illusion” is “an erroneous mental representation”. This

may be an artifact of WordNet definitions since WordNet places each sense in a hie-

rarchy of hyponymy relation, which covers both concrete and abstract concepts.

Words like “disposition” and “representation” are nevertheless abstract even when

they are the genus terms for other words. To this end, we plan to check against other

dictionaries and explore possible ways to deal with various kinds of genus terms, to

refine the concreteness index induced from definition categories.

In the current study, our human ratings on lexical and sense concreteness came

from non-native speakers of English. Although we found a high degree of agreement

between their ratings with those by native speakers, the cultural difference may have

influenced the familiarity of the raters with the word samples and thus the context

availability associated with individual words.

Also, in the current study, we have only started with and focused on one of the

possible external evidence for lexical concreteness, namely dictionary definition

styles. Given that human ratings on concreteness may be a result of the interaction of

many factors including word frequency, context availability, imageability and access

to sensory referents, etc., it will be appropriate for us to resort to other sources of

external evidence such as word association norm data, authentic linguistic context

from corpus data, domain information, etc. for a more realistic and complete model of

lexical concreteness. Hence, apart from refining our analysis and categorisation of

definition styles based on more dictionaries, as pointed out above, our next steps will

focus on the extension toward other data sources for modelling the concreteness dis-

tinction and simulating the concreteness index. This will also be investigated in rela-

tion to the various competing theories on why abstract words are harder to understand,

thus drawing from both psycholinguistic findings and existing language resources to

achieve a cognitively plausible computational simulation of the concrete-abstract

distinction. Moreover, further studies will be conducted to examine the effect of

lexical and sense concreteness on the information demand of automatic word sense

disambiguation and the use of concreteness for indicating potentially confusable

senses for better evaluation of disambiguation performance, as suggested in [8].

7 Conclusions

In this paper we have reported on our preliminary study on simulating human judge-

ments on the concreteness or abstractness of words. We have analysed and catego-

rised dictionary definitions from their surface syntactic forms, which is assumed to

92

relate to the various levels of concreteness of the concepts being defined. The overall

agreement found between human ratings and definition-induced ratings is encourag-

ing for us to further pursue on the simulation of a numerical index for lexical and

sense concreteness from more language resources. Such an index is believed to in-

form not only lexicography but also natural language processing tasks like automatic

word sense disambiguation.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from the Research

Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No.

CityU 1508/06H).

References

1. Bleasdale, F.A. (1987) Concreteness dependent associative priming: Separate lexical

organization for concrete and abstract words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learn-

ing, Memory, and Cognition, 13:582-594.

2. DeGroot, A.M.B. (1989) Representational aspects of word imageability and word frequen-

cy as assessed through word association. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

Memory, and Cognition, 15:824-845.

3. Jackson, H. (2002) Lexicography: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge.

4. Kroll, J.F. and Merves, J.S. (1986) Lexical access for concrete and abstract words. Jour-

nal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12:92-107.

5. Kwong, O.Y. (2005) Word Sense Classification Based on Information Susceptibility. In A.

Lenci, S. Montemagni and V. Pirrelli (Eds.), Acquisition and Representation of Word

Meaning. Linguistica Computazionale, pp.89-115.

6. Kwong, O.Y. (2007) Sense Abstractness, Semantic Activation and Word Sense Disam-

biguation: Implications from Word Association Norms. In Proceedings of the 4th Interna-

tional Workshop on Natural Language Processing and Cognitive Science (NLPCS-2007),

Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, pp.169-178.

7. McKeown, M.G. (1991) Learning Word Meanings from Definitions: Problems and Poten-

tial. In P.J. Schwanenflugel (Ed.), The Psychology of Word Meanings. Hillsdale, NJ: Law-

rence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp.137-156.

8. Resnik, P. and Yarowsky, D. (1999) Distinguishing systems and distinguishing senses:

new evaluation methods for Word Sense Disambiguation. Natural Language Engineering,

5(2):113-133.

9. Schwanenflugel, P.J. (1991) Why are Abstract Concepts Hard to Understand? In P.J.

Schwanenflugel (Ed.), The Psychology of Word Meanings. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erl-

baum Associates, Inc., pp.223-250.

10. Swinney, D.A. (1979) Lexical access during sentence comprehension: (Re)consideration

of context effects. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18:645-659.

11. WordNet 3.0, http://wordnet.princeton.edu/

12. Yore, L.D. and Ollila, L.O. (1985) Cognitive development, sex, and abstractness in grade

one word recognition. Journal of Educational Research, 78:242-247.

93