Verbal Fluency, or How to Stay on Top of the Wave?

Michael Zock

1

and Stergos D. Afantenos

2

1

LIF, CNRS (UMR 6166), Université de la Méditerranée

Faculté des Sciences de Luminy, France

2

LINA, (UMR CNRS 6241), Université de Nantes, France

Abstract. Speaking a language and achieving proficiency in another one is a

highly complex process which requires the acquisition of various kinds of knowl-

edge and skills, like the learning of words, rules and patterns and their connec-

tion to communicative goals (intentions), the usual starting point. To help the

learner to acquire these skills we propose an enhanced, electronic version of an

age old method: pattern drills (henceforth PDs). While being highly regarded in

the fifties, PDs have become unpopular since then, partially because of their lack

of grounding (natural context) and rigidity. Despite these shortcomings we do

believe in the virtues of this approach, at least with regard to the acquisition of

basic linguistic reflexes or skills (automatisms), necessary to survive in the new

language. Of course, the method needs improvement, and we will show here how

this can be achieved. Unlike tapes or books, computers are open media, allowing

for dynamic changes, taking users’ performances and preferences into account.

Building an electronic version of PDs amounts to building an open resource, ac-

comodatable to the users’ ever changing needs.

1 Introduction

To speak a language fluently is a very complex task, to do so in a foreign language

can be overwhelming. Next to cognitive overload, there are at least three reasons for

this: lack of knowledge, lack of assurance and lack of remembrance. Indeed, learning

to speak a new language requires not only learning a stock of new words and rules,

but also to have the necessary confidence to dare to speak, which supposes, of course,

quick access and remembrance of what has been learned. To achieve these goals (in-

crease/consolidation of knowledge, boosting of confidence, fixation/ memorisation) we

have enhanced an age-old method, pattern drills, by building an electronic version of it.

While the drill tutor (henceforth DT) is built for learning Japanese, we believe that the

method is general enough to be applied to other languages.

PDs are a special kind of exercise based on notions like: analogy, task decompo-

sition (small steps), systematicity, repetition and feedback. Important as they may be,

PDs, or exercices in general, are but one of the many tools teachers rely on for teach-

ing a language. Dictionaries, grammars, video and textbooks being supplementary re-

sources. None of them, except the first one will be taken into consideration here. PDs

are typically used in audio-oral lessons. Such lessons are generally composed of the

Zock M. and D. Afantenos S. (2008).

Verbal Fluency, or How to Stay on Top of the Wave?.

In Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Natural Language Processing and Cognitive Science, pages 159-164

DOI: 10.5220/0001742001590164

Copyright

c

SciTePress

following steps: (1) Presentation of a little drama, where people try to solve a commu-

nication problem (hotel, train station, barber shop). The student hears the story and is

encouraged to play one of the roles; (2) Contrastive examples for rule induction; (3)

Rule fixation via pattern drills; (4) Re-use of the learned rules or pattern in a different

situation (tranposition / generalization). These four stages fulfill, roughly speaking, the

following functions (a) symbol grounding, i.e. illustration of the pragmatic usage of the

structure; (b) conceptualization, i.e. explanation/understanding of the rule; (c) memo-

rization/automation of the patterns, and (d) transposition/consolidation of the learned

material. Obviously, there are many ways to learn a language, yet, one of them has

proven to be quite efficient, at least for survival purposes: PDs.

3

Since PDs are neither a new nor an uncontroversial method, let us show how some of

their shortcomings can be overcome. Of course, people learn not only patterns, but also

the situations (context) in which they occur. The latter can be seen as goals: meeting

someone introduce oneself, hearing him ask for a favor or offering help, the learner

realizes that the person s/he is observing uses over and over the same pattern, though

not necessarily always in the same situation. Given this tight connection between means

(patterns) and ends (goals), we have decided to integrate this link in our DT: the fact that

patterns are indexed in terms of goals allows the user to choose the means (patterns) as a

function of the end (goal, input). People are generally little motivated to do something,

unless they perceive its use, that is, the purpose a given action is serving for (means).

2 An Example of the Process

Before showing how the resource is built, let us see how it is meant to work and in what

respect it differs from conventional PDs used in a language lab. Let’s start with the lat-

ter, illustrating it with the simplest case, substitution drills requiring no morphological

changes. The student receives a model, which could be composed of a question (let’s

say, “what is this?”), a stimulus (“a pen”) and the answer (“This is a pen”). From then

on, s/he will only be given the stimulus and the feedback concerning his answer (the

machine producing the correct sentence). Of course, the user has to produce the answer

in the first place.

While being similar to classical PDs, our approach is nevertheless quite a bit dif-

ferent. First of all, it is the student who chooses the pattern s/he’d like to work on, as

s/he knows (arguably) best what her/his needs are. Next, our patterns are indexed in

terms of goals. This is necessary in order to locate or find the pattern one would like to

3

After having been very popular for many years, PDs and instrumental conditioning upon

which they rely have been discredited by linguists (see Chomsky’s violent criticism [1] of Skin-

ner’s book Verbal Behavior, an attempt to provide an operational account of language), and more

directly by psychologists [2, 3] and pedagogues [4, 5]. While we do agree with these criticisms,

when the process of language production or the architecture of the human mind are at stake, we

do not share them at all when habit formation or the acquisition of linguistic reflexes, i.e. au-

tomatisms are the learning goal [6]. For this specific task, we do believe that principled ways of

staging the repetition of stimulus-response patterns together with feedback are a valuable learn-

ing method. Interestingly enough, patterns have been rehabilitated by one of Chomsky’s most

brilliant students [7].

160

Compare

yourself

Question

direction

name

price

price

people

object

Goal Tree (list of goals)

Sono kata wa doitsu no Sumisu desu

Goal

English pattern

Japanese pattern

Present

somebody

2 This is <title> <name> from <origine>

Sono kata wa <origin> no <name> <title>desu

This is Mr. Smith from Germany.

Sono kata wa <doitsu> no <Sumisu> <san> desu

1 This is <title> <name>

<title>

<name>

<origin>

Mr, Mrs, Dr., professor

Matsumoto, Schmidt, Tanaka, Tsuji

Japan, Germany, France

Kore wa <name> <title> desu

This is Prof. Tsuji from Japan

Sono kata wa <nihon> no <Tsuji> <sensei> desu

A

somebody

Present

Provide values (words) for the variables

Choose one of the patterns

Set of possible outputs

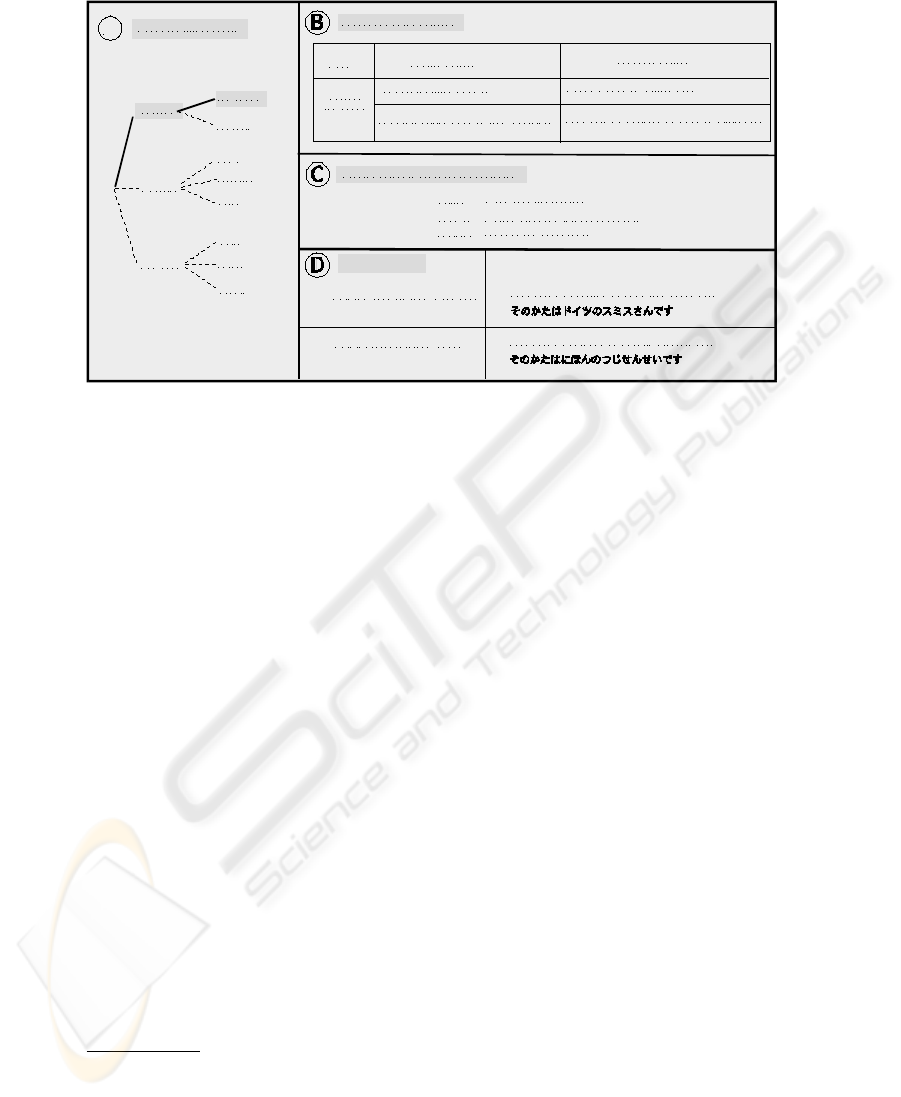

Fig. 1. The basic interaction process between the DT and the student.

work on. With the system growing, grows the list of patterns. Hence, access becomes

an issue. Also, associating patterns with goals allows the student to realize the pattern’s

communicative function. Third, since we don’t have a parser or speech recognizer, we

have a problem concerning the user’s output. Actually, the learner does not type at all,

s/he only confirms via a keystroke that his/her mentally (or orally produced) answer

conforms to the system’s output. The reason for this is simple. The focus being on

speed (fluency), we’d like to avoid slowing down the process by having the input being

provided via the keyboard. Fourth, the system’s output is also written. This can be con-

sidered as a disadvantage, yet it can also be turned into a big advantage if, as planned,

a speech synthesizer is added. Doing so would allow not only to discover grapheme-

phoneme mappings, hence support the learning of reading and writing, but also allow

to support memorization by showing intonation curves. In addition this would allow us

to control the speed of the vocal output, which leads us to the last point. Unlike tapes,

with computers we can change at any moment parameters like (a) speed; (b) order of

examples, (c) staging of repetitions, i.e. number of repetitions after which an element is

taken from the list, to maximize presentation of problematic cases, etc.

Figure 1 above illustrates the way how the student gets from the starting point, a

goal (frame A), to its linguistic realization, the endpoint (frame D) by using the DT.

The process is initiated via the choice of a goal (introduce somebody, step 1, frame A)

to which the system answers with a set of patterns (step 2, frame B). The user chooses

one of them (step 3: B1 vs. B2), signalling then the specific lexical values with which

s/he would like the pattern to be instantiated (frame C, step 4). The system has now

all the information needed to create the exercise (frame D), presenting sequentially a

model,

4

the stimulus (chosen word), followed by the student’s answer and the system’s

4

The latter is basically composed of a sentence (step 1), a stimulus (the lexical value of the

variable, step 2), and the new sentence based on the model and the stimulus (step 3).

161

confirmation/information (normally also a sentence, implying that the student’s answer

is correct if the two sentences match and incorrect in the opposite case). The process

continues until the student has done all the exercices, or until s/he decides to stop.

Note that, if the values of the variables <title>, <name>, <origin> were (professor,

Tsuji, Japan) rather than (Mr, Smith, Germany), then the outputs would vary, of course,

accordingly.

It should be noted that at the moment, we do not rely on any morphological compo-

nent which obviously limits the system’s scope. Any question-answer pair or sentence

transformation may require such a component, and we will surely integrate it later on.

5

For the time being, the idea is just to illustrate the system’s basic mechanism and the

interaction between the system and the student.

3 Current State of the Drill Tutor

The DT is a client/server web application written in PHP and sitting atop an Apache

server in a Linux machine. The DT is divided into two separate areas: one reserved

for data acquisition linking words, patterns and goals (Expert Area), the other being

reserved for exercising (Student Area). The implemented operations are as follows.

3.1 Expert Area

User Authentication. People entitled to make changes to the database (experts) have

to authenticate themselves. This is necessary to ensure that people work on their own

data and to avoid inconsistencies in the database.

Creation of New Patterns and Goals. Currently the system has about 50 patterns and

500 words.

6

To allow for quick access, patterns need to be indexed. This is done here

via goals. Of course, other criteria could be used. In order to provide new data (typically

a new goal and its associated patterns and words) the expert can either use the system’s

graphical user interface (henceforth GUI), or upload a file containing the necessary

information. Once this is done, the system presents the expert all possible sentences

computable on the basis of the input, allowing him to check them for well-formedness.

5

Once such a morphological component is added, conceptual input would take place in three-

steps: at a global level the learner chooses the pattern via a goal, next s/he provides lexical values

for the pattern’s variables, to refine then this global message by specifying morphological values

(number, tense). This approach would be much more economical for storing and accessing pat-

terns, than storing a pattern for every morphological variant. It would also be much faster than

navigating through a conceptual ontology.

6

Actually, the number of patterns and the size of the vocabulary is not really what counts at

this stage, as the focus is on the implementation of an editor designed for building, modifying

and using a database. Also, while it would have been easy to copy patterns from one of the many

textbooks [8, 9], we have refrained from doing so, not only for reasons of copyright, but also

for reasons of metalanguage. The terms in which these patterns are defined are neither always

consistent nor very felicitous.

162

Structuring Goals into Trees. Learners knowing their needs prefer to make their own

choices rather than being told what patterns to work on. To do so, we must give them the

means to express their needs, or, in this particular case, to locate the relevant patterns

in an ontology or goal tree (see also Figure 1). To enable the system to create this kind

of structure, experts have to state with their input where in the hierarchy fits their new

goal and its associated pattern(s). This is done via the parent node.

Modification of Goals. The data given to the system (goals, patterns and lexical values)

can be modified at any time. In other words, experts can add, delete or modify the

patterns and values for any goal inserted.

Visualization of the Database. The data given can be visualized as a table which can

be useful for checking completeness and consistency of the patterns, or for appreciating

the adequacy of the metalanguage.

3.2 The Student Area

Working on the Exercises. The students can choose the pattern they’d like to work

on. To find the wanted pattern they navigate in the goal hierarchy. Once they’ve found

the goal they will be presented with all its associated patterns, meaning that they have

to choose again, though, this time from a much smaller set. The process develops as

follows. First, students are shown an example sentence (model) in which a single ele-

ment will be replaced. In the simplest case (substitution drill), only one element will be

replaced, no morphological changes taking place. Next are given, in random order, the

elements (stimulus) to be inserted into the proper slot. Doing so should help the students

not only to memorize words, but also to use (or to produce) them in the proper syntactic

context. Finally, students are shown the correct sentence both in roman characters as

well as in their transliterated Japanese form (for the time being only in Hiragana). The

process iterates until the student has acquired the patterns or has decided to stop.

These are the main steps of the process. In addition, users are allowed to define key-

board shortcuts, using keystrokes rather than moving the mouse over radio buttons. This

increases speed and confort for telling the system that one has been able to produce the

expected output, information necessary to decide whether a given combination (pattern

+ specific word) should be kept on the exercise list. Students can also choose their own

metalinguistic terms and interface language. This allows people to study Japanese via

a language they feel most comfortable with. Language specific problems like counters,

time and family relations are dealt with via specific exercices.

Evaluation. Of course, the whole process would be of little use if the students were

not given some means (feedback) to assess the quality of their work. Actually, the sys-

tem keeps track of the users’ performance (errors made during the training session),

allowing thus to allocate more time to problematic cases (optimization of memorisation

schedule). A problem that remains though is the fact that the user’s output is purely

quantitative: congruency of his and the system’s output. Not having access to the con-

crete form of the output, the system cannot fully interpret it (What went wrong? Why?

How to correct the mistake?) and provide explanations.

163

4 Conclusions

Becoming fluent in a language requires not only learning words and methods for access-

ing them quickly, but also learning how to place them and how to make the necessary

morphological adjustments. This is not a small feat, considering that all this has to be

done fast, and on top of it, content must be planned.

The work presented here is the result of less than 12 months’ work. It is imple-

mented in PHP, and the supported languages are English at the interface level and

Japanese as the language to be learned. We plan to add other languages, a speech syn-

thesizer and a morphological component. We also intend to make the system available

on the web in the near future.

Having linked patterns to goals should help users to perceive the function of a given

structure (i.e which goal(s) can be reached by using a particular pattern). Yet, most

importantly, this linkage offers the possibility to get instances of the pattern from a

document (corpus). This is interesting not only for data acquisition (building the re-

source by feeding it with lexical entries likely to occur in a given pattern), but also for

remembrance. In addition, presenting patterns with new material allows expanding the

learner’s experience of the language. The fact that most goals are associated with mul-

tiple patterns allows to extend the range of the exercise, reducing thus boredom. Instead

of drilling one single pattern in response to a chosen goal, the system can prompt the

user by presenting him various patterns.

Obviously, PDs are not a panacea, yet used in the right way they can do wonders.

Just like a tennis player might want to go back to the court and train his basic strokes,

a language learner may feel the need to drill resisting patterns. We must beware though

that patterns are just one element of a long chain. They need to be learned, but once

interiorized they must be placed back into the context where they have come from, a

real communicative scene. Without this additional experience they will simply fail to

produce the wanted effect, that is, help us achieve our communicative goals.

References

1. Chomsky, N.: A review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Language 31 (1959) 26–58

2. Herriot, P.: Language and Teaching: A Psychological View. Methuen and Co, London (1971)

3. Levelt, W.: Skill theory and language teaching. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 1

(1970) 53–70

4. Chastain, K.: The audio-lingual habit learning theory vs. the code-cognitif learning theory.

IRAL 7 (1969) 97–107

5. Rivers, W.: The Psychologist and the Foreign Language Teacher. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago (1964)

6. Fitts, P.: Perceptual motor skill learning. In Melton, A.W., ed.: Categories of human learning.

Academic press, New York (1964) 243–285

7. Jackendoff, R.: Patterns in the Mind: Language and Human Nature. Harvester-Wheatsheaf

(1993)

8. Alfonso, A.: Japanese language patterns. Volume 1. Sofia University, Center of Applied

Linguistics, Tokyo (1974)

9. Chino, N.: A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Sentence Patterns. Kodansha, Tokyo (2004)

patterns.

164