ADOPTION VERSUS USE DIFFUSION

Predicting User Acceptance of Mobile TV in Flanders

Tom Evens, Lieven De Marez

Research Group for Media & ICT (MICT-IBBT), Ghent University, Korte Meer 7-9-11, Gent, Belgium

Dimitri Schuurman

Research Group for Media & ICT (MICT-IBBT), Ghent University, Korte Meer 7-9-11, Gent, Belgium

Keywords: User research, adoption diffusion, use diffusion, mutual shaping, mobile TV.

Abstract: In the contemporary changing ICT environment, an increasing number of services and devices are being

developed and brought to end-user market. Unfortunately, this environment is also characterized by an

increasing number of failing innovations; confronting scholars, policy makers as well as industry with an

explicit need for more accurate user research. Such research must result in more accurate predictions and

forecasts of an innovation’s potential, as a basis for more efficient business planning and strategy

implementation. However, the success of a new technology is not only depending on the adoption decision

and the number of people actually buying it, but relies at least as much on its actual usage. Hence, the focus

of truly user-oriented acceptance or potential prediction should focus on predicting both adoption diffusion

and use diffusion. Within this paper, we illustrate the added value of such an interactionist approach for the

study of future adoption and usage of mobile TV by the assessment of both a large-scale intention survey

and qualitative techniques such as diary studies, focus group interviews, observational and ethnographic

methods.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the contemporary changing ICT environment, an

increasing number of services and devices are being

developed and brought to end-user market.

Unfortunately, this environment is also characterized

by an increasing number of failing innovations;

confronting scholars, policy makers as well as

industry with an explicit need for more accurate user

research. Such research must result in more accurate

predictions and forecasts of an innovation’s

potential, as a basis for more efficient business

planning and strategy implementation.

In most cases however, this need for more

accurate user insight only gets translated in a cross-

sectional investigation of the innovation’s adoption

potential. However, the success of a new technology

or service is not only depending on the adoption

decision and the number of people actually buying

it. For example, many people may have bought or

adopted a mobile phone with GPRS, UMTS or

MMS without using the feature. The success of an

innovation is thus not only depending on its

adoption, but at least as much on its usage. Hence,

the focus of truly user-oriented acceptance or

potential prediction should not only be focussed on

predicting adoption diffusion, but also on predicting

use diffusion and potential usage. Evidently, the first

research question to answer remains up to which

degree the innovation has the potential to be

adopted. This should always be accompanied with

an answer to the question up to which degree the

innovation also has the potential to acquire a place in

people’s and household’s daily lives (in terms of

time and habits).

In terms of theoretical frameworks, the first

‘adoption diffusion’ question relies on the diffusion

paradigm, while the second ‘use diffusion’ question

relies on the ‘social shaping’ and ‘domestication’

paradigm. Too often however, the Social Shaping of

Technologies (SST) and Domestication perspective

is considered as the alternative to set off the lack of

attention for the user and his/her social usage

context in the diffusion theory. Traditionally, both

perspectives (and the research based on them) have

too much been considered as opposites; while they

124

Evens T., De Marez L. and Schuurman D. (2008).

ADOPTION VERSUS USE DIFFUSION - Predicting User Acceptance of Mobile TV in Flanders.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 124-130

DOI: 10.5220/0001907201240130

Copyright

c

SciTePress

are perfectly complementary to each other. The

purpose of this paper is to illustrate this

complementariness and the enrichment of combining

the more quantitative generalizing research approach

of diffusionism with the more qualitative in-depth

SST research approach. Based on user research

conducted on mobile TV, we illustrate how this

combination of approaches and methods resulted in

a prediction of potential as well as usage of this new

technology. This way, we intend to illustrate the

theoretical, methodological, managerial as well as

policy relevance of this plea for a more mutual

shaping or interactionist approach on predicting user

acceptance (see Boczkowski, 2004: 255).

2 TWO COMPLEMENTARY

FRAMEWORKS

The oldest of the two theoretical frameworks is the

‘diffusion framework’, of which Everett M. Rogers

(1962) is assumed to be the founding father.

According to this framework, the diffusion of

innovations in a social system always follows a bell-

shaped normal distribution, in which there can be

successively distinguished between Innovators

(2.5%), Early Adopters (13.5%), Early Majority

(34%), Late Majority (34%) and Laggards (16%). A

person’s innovativeness is assumed to be determined

by the perception of the following set of innovation

characteristics: relative advantage, complexity,

compatibility, trialability and observability (Rogers,

2003). Since the early 60’s the theory’s assumptions

on segment sizes, diffusion pattern and determinants

have been a basis for different types of (mostly)

quantitative research such as econometric diffusion

modelling or innovation scales (Goldsmith &

Hofacker, 1991; Meade & Islam, 2006; Moore &

Benbasat, 1991; Parasuraman & Colby, 2001;

Venkatsh, Morris, Davis & Davis, 2003).

Since the mid 80’s however, questions about its

technological determinism and lack of attention to

the user and usage of the innovation have induced

Rogers to adjust his approach to the adoption

decision process, but have also led to the rise of new

paradigms such as domestication focussing on the

‘way the use in households is being socially

negotiated and becomes meaningful, within the

social context of class, gender, culture or lifestyle’

(Van Den Broeck, Pierson, Pauwels, 2004: 103;

Haddon, 2007; Silverstone & Haddon, 1996) or ‘the

process of taming and house training ‘wild’

technological objects, by adapting them to the

routines and rituals of the household and thus giving

them a more or less natural and taken-for-granted

place within the microsocial context of that

household’ (Frissen, 2000: 67; Jankowski & Van

Selm, 2001: 37). Domestication thus refers to

integration of new technologies in the daily patterns,

structures and values of users, relying on a more

social determinism (Bouwman, Van Dijk, Van den

Hooff & van den Wijngaert, 2002).

Methodologically, the SST and domestication

paradigm relies more on a qualitative tradition of

methods such as in-depth interviews, ethnographic

observation and diary studies.

In the past, these two major paradigms have

mostly been regarded as opposite and competing,

with convinced advocates from the two sides

engaging in vicious debates. However, with

diffusionism as the more quantitative tradition with

the focus on acceptance and adoption decisions and

the domestication tradition as more qualitative with

a focus on the use and appropriation of technologies,

both paradigms are clearly complementary (Punie,

2000). Or, as Boczkowski (2004: 255) states, ‘two

sides of the same innovation coin’. To date a

dialectical approach, which considers the

development and diffusion of ICT innovations as

‘joint processes of technological construction and

societal adoption’ (Boczkowski, 2004: 257), gains

ground. Instead of thinking in terms of diffusionism

or social shaping, the mutual shaping or

interactionism approach (Boczkowski, 2004;

Lievrouw & Livingstone, 2006; Trott, 2003)

appeared in the late 90’s as a dynamic middle path

between the two previous linear deterministic

predecessors. By integrating both quantitative and

qualitative research outcomes within this paper, we

aim to illustrate the enrichment of such an

interactionist approach for the development and roll-

out of mobile TV in Flanders, the northern and

Dutch-speaking part of Belgium.

Relying on the difference between ‘adoption

diffusion’ and ‘use diffusion’ (Shih & Venkatesh,

2004), we believe that the prediction of ‘adoption

diffusion’ should rely on (1) a quantitative diffusion

approach by means of (intention) surveys and

modelling to gain insight in the innovation’s

potential in terms of percentage of the target market,

penetration pattern and profiles of the different

adopter segments; and (2) the prediction of ‘use

diffusion’, based on more qualitative techniques

such as diary studies, focus group interviews,

observational and ethnographic techniques (if

possible in a field trial or living lab setting).

ADOPTION VERSUS USE DIFFUSION - Predicting User Acceptance of Mobile TV in Flanders

125

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

The empirical findings are based on the two-year

MADUF project which studied the possibilities of

mobile TV using DVB-H in Flanders. In first

instance, a large-scale user survey (n: 575) was set

up in order to forecast the market potential, or to

predict the ‘adoption diffusion’ potential for mobile

TV in Flanders. By applying the Product Specific

Adoption Potential (PSAP) scale, we were able to

map the size and nature of the future mobile TV

market in Flanders. The PSAP scale is an intention

based survey method in which respondents are

allocated to Innovator, Early Adopter, Majority and

Laggard segments based on the stated intentions on

a general intention question and on respondent-

specific formulated questions gauging for their

intention for ‘optimal’ and ‘suboptimal’ product

offerings (De Marez & Verleye, 2004; Verleye & De

Marez, 2005). The scale was compared on its

reliability with five other adoption models and has

been applied to and validated for a diversity of ICT

innovations such as digital TV, 3G, mobile TV and

mobile news (De Marez, 2006; De Marez, Vyncke,

Berte, Schuurman & De Moor, 2008).

In second instance, a representative panel of test

users was randomly selected from the 575 survey

respondents to experiment with mobile television

devices in a ‘living lab’ setting during two weeks.

Due to practical reasons (the DVB-H network was

operational in the city of Ghent only, so the panel

contained people exclusively living but not

especially working in Ghent) and because of the

rather explorative nature of this field trial, the

amount of test users was limited to 30. With this

field trial, we aimed at achieving a first realistic

view of how future users will integrate mobile TV in

their everyday practices. Users were asked to

document their experiences in diaries while logging

their activities, noting their comments and taking

pictures of their usage situations.

Next to these data, we also gained insight in their

personal evaluation of the trial phase by means of a

post-measurement. Comparing these results with the

findings of the market forecast before testing the

device allowed us to see whether user attitudes

towards mobile television had changed as a result of

the trial. In this manner, we aimed to measure the

effect of trialability, the degree to which an

innovation may be experimented with on a limited

basis (Rogers, 2003: 266). Explanations for possible

shifts between the pre- and the post-measurements

can be found in the usage diaries and two organised

focus groups. Figure 1 illustrates this interactionist

approach combining both quantitative user attitude

research and qualitative ethnographic techniques.

Figure 1: Interactionist research design.

4 RESULTS: PREDICTING

ADOPTION DIFFUSION

By applying the PSAP scale to 575 rich cases, we

obtained a reliable view on the size and nature of the

various adoption segments for mobile TV in

Flanders in the following segmentation forecast.

While traditional fixed segment sized methods are

reflected by the black line (in this case Rogers’

Diffusions of Innovations), the red line represents

the adoption potential for mobile TV. The latter is

contrasted to the potential of 3G (De Marez, 2006),

which allows TV programmes to be received over a

unicast architecture network. Figure 2 clearly shows

that there is little demand for mobile TV over DVB-

H compared to Rogers’ full market approach and

even compared to the take-up of 3G services. Due to

the lack of substantial innovative segments

(Innovators and Early Adopters), we would

recommend a partial market approach or even a

niche strategy for the introduction of mobile TV in

Flanders. This implies a specific introduction

strategy for a limited market potential to serve the

chosen segments in an optimal manner (about a 20%

market penetration). Since the Late Majority and

Laggard segment are clearly not willing to pay for

this mobile service, we will define the maximal

target group as Innovators, Early Adopters and Early

Majority promising a 16,7% segmentation forecast.

Figure 2: Segmentation forecast mobile TV.

In general, we witnessed a rather dual profile

within the innovative segments with on the one hand

well-earning, older executives (little time, potential

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

126

for snacking) and on the other hand low educated

young couples without children (much time,

complementary to heavy TV viewing behaviour).

Although especially executives are facing a shortage

of time, most of them seem to be heavy television

viewers, watching both entertainment and

information programs. Especially Innovators and

Early Adopters (joint for statistical reasons) possess

advanced mobile phones (with camera, MMS, WAP,

MP3, FM radio…), which they use in an innovative

manner (e.g. sending e-mails on mobile phone, see

Figure 3). Generally, these people show the highest

willingness to pay for mobile TV while most of

them consider a mobile TV device (with integrated

mobile phone) as a substitute for their current

mobile phone.

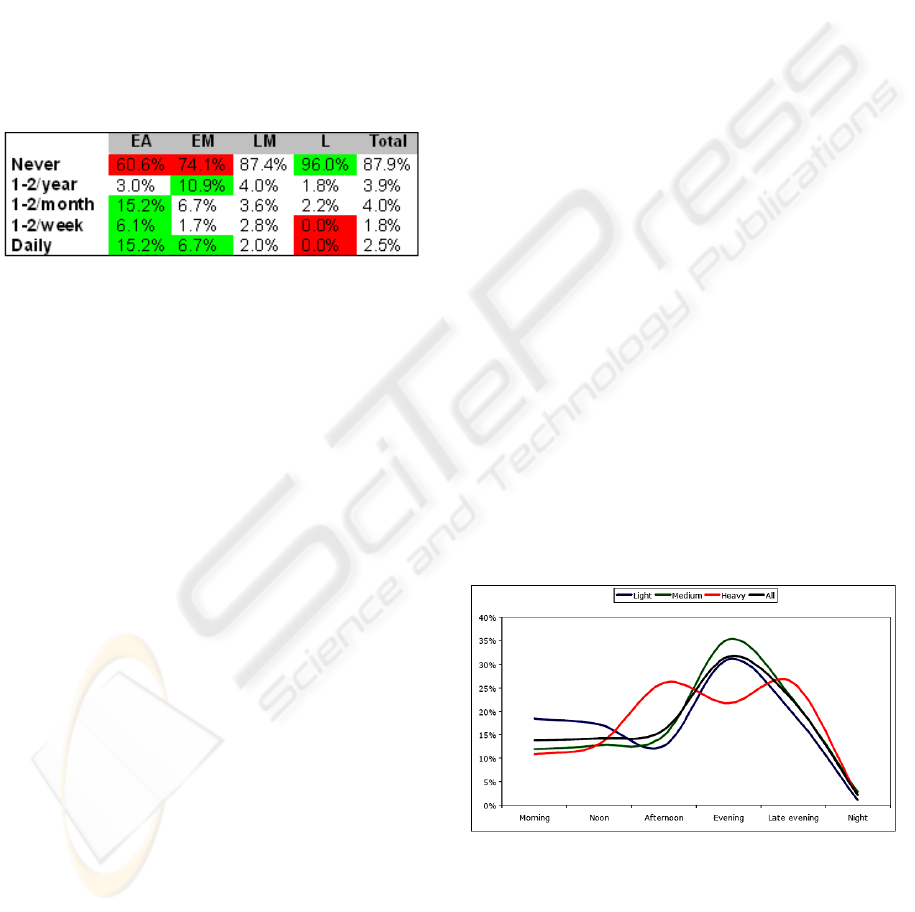

Figure 3: Sending e-mails on mobile phone

Clearly, such quantitative research may provide

reliable estimations of the adoption potential and

diffusion (in this case of mobile TV in Flanders), but

does not provide us with in-depth information

regarding the domestication and potential use

diffusion of mobile TV. What place will it take in

the lives of the consumers, how and when will it be

used?

5 RESULTS: PREDICTING USE

DIFFUSION

To answer the latter questions, one needs a more

qualitative ‘use diffusion’ and domestication

oriented research framework. In the case of mobile

television a combination of diaries, focus group

discussions, pre-post test comparisons and photo

elicitation within the boundaries of a living lab

setting was used to get further insight in people’s

usage patterns of mobile TV. Although we are aware

these results are not statistically representative due

to the very limited sample of 30 test users, they

nevertheless allow us to identify some explorative

usage patterns for mobile TV amongst our field trial

participants.

On average, people watched approximately

eleven times via their mobile television device

during the two-week test period. However, it is

possible that people being part of a panel within a

test environment felt obliged to experiment more

with the devices than they would do within a more

natural context. Although we cannot ignore this trial

effect, it plays a less important role within this

research set-up because we aim to generate

explorative rather than statistically representative

findings. In terms of this usage frequency pattern,

we can distinguish three kinds of viewers: light

viewers watching less than 10 times (n: 15), medium

viewers watching between 10 and 20 times (n: 13)

and heavy viewers watching more than 20 times (n:

2). These two heavy viewers were identified as

Innovator and Early Adopter within our large-scale

sample.

Within our user panel, we only found two heavy

viewers while the rest of the panel was about equally

divided among medium and light viewers. One

important finding during our test period is that the

different types of viewers used the mobile TV

device in a different way. Figure 4 represents all

watching moments and divides them amongst the

periods people watched mobile TV. In terms of the

moments people watched mobile TV, we identified

six different time slots: night (0-6h), morning (6-

12h), noon (12-14h), afternoon (14-18h), evening

(18-22h) and late evening (22-24h). When analysing

the figure, we see that, except for the light viewers,

trial participants are not inclined to watch mobile

TV while having breakfast. This is probably due to

the strong position in the morning of the medium

radio, which is ‘together with the water and the

stove, the first thing that is turned on in the morning’

(Winocur, 2005: 325). Light viewers are also more

likely to watch mobile television at noon while

having dinner.

Figure 4: Usage patterns (per time slot).

Heavy viewers are most likely to watch mobile

during the afternoon, while most of the other types

of viewers only switch their device on in the evening

after coming home from work or school (see Figure

4). While light and medium viewers are watching

mobile TV in the evening, we notice a remarkable

ADOPTION VERSUS USE DIFFUSION - Predicting User Acceptance of Mobile TV in Flanders

127

decline in viewing of the heavy viewer-segment

during this time slot (see red line). Nevertheless, we

see that this segment starts watching again in the late

evening, the moment where the other segments

switch their device off. This results in peaked

watching patterns that differ quite much between the

three user segments. While light and medium users

show one viewing peak during the evening, heavy

viewers have two peaks: one in the afternoon and

one in the late evening. The latter two-peaked

pattern is rather complementary with traditional TV,

as its peak time comes right in between the mobile

peak times. We can conclude that heavy viewers

used mobile TV complementary to their regular

television and therefore watched the device in a

manner it was meant to be watched: on the move. In

contrast, light and medium viewers watched mobile

TV at home as a substitute for regular television.

The previous findings are supported by the usage

locations indicated in the diaries. Light and medium

viewers especially watched mobile TV at home.

Undoubtedly, the most popular place was the living

room where people are used to watch regular

television while relaxing in their sofa. This also

seemed the case for mobile TV: most people

watched television in their natural habitat. Instead of

watching the large screen, our test users watched

mobile TV, albeit for a rather short period. After

having tested the mobile device, they switched to the

large screen again to enjoy their favourite programs.

Here, we witnessed a substitution

of the classical

screen at traditional peak times with mobile TV was

considered a second TV (see also Schuurman et al.,

2008). This was especially the case for the light and

medium users in our sample. This does explain the

similarities between peak times for mobile and

regular TV for these groups.

Another popular location for watching mobile

TV was the kitchen. People seem to enjoy watching

mobile TV while eating in the kitchen, where most

of the time no TV set is at hand. We also witnessed

that a lot of people used the mobile device while

working at their desk or sitting behind the computer.

These people used mobile TV rather as a

background

medium or as tertiary activity (see

Jacobs, Lievens, Vangenck, Vanhengel & Pierson,

2008). When they heard something interesting, they

switched attention from their work to the mobile

device. Although they watched mobile television,

these people considered the mobile television device

often as a radio, which is in most cases also used as

a background medium. Here mobile TV was clearly

used in combination with other activities such as

doing the dishes or working (multitasking).

Especially heavy viewers made use of the

complementary function

of mobile TV and

considered it as an extra supply next to their regular

television. This is illustrated by the fact that heavy

viewers watched significantly more in public space

and on the move. We found that watching in the car

is a rather popular activity to kill time, sometimes as

fellow passenger but also as driver. These people

driving to their work and back, spend a lot of time in

their car and have to suffer traffic jams. It is hardly

surprising that in such cases mobile television is

seen as a simple time killer although the radio can

serve this purpose as well. Other persons preferred

watching mobile TV while waiting for or travelling

with public transport services (bus, metro and train).

Taking into account the massive success of the iPod,

mobile TV devices can be the next big thing to

spend time while commuting.

After the trial period, we asked our 30 test users

to fill out the same questionnaire they had

previously taken. Based on the combined results of

both pre- and post-trial measurement, we were able

to compare the findings and see whether user

expectations and attitudes had changed during the

mobile TV field trial. The findings from the

qualitative part of this research project (i.e. focus

groups and ethnographic methods such as usage

diaries) enabled us to explain possible shifts.

General interest for mobile TV slightly increased

during the field trial. However, persons who

originally intended to purchase a mobile TV device

soon, now preferred to wait a bit longer. On the

other hand, the amount of people certainly not

willing to purchase a mobile TV device declined as

well. A slightly increased average score (from 3,70

to 3,80) suggests that overall attitude towards mobile

TV became a little bit more positive. Also the

average price people are willing to pay increased

from €233 to €294. But it is striking that we witness

a converging shift towards a non-decisive average.

Convinced believers start to doubt while disbelievers

might have seen some possibilities after all due to

the trial.

In other words, less people are showing an

innovative attitude towards mobile TV, but many

others shifted from ‘never’ to ‘maybe’. It thus seems

that the field trial has raised awareness of mobile TV

and that a lot of people do not consider the medium

as a luxurious product any longer, making it less

appealing to the more innovative but more likely to

consider for the less innovative. Although these

people are not likely to purchase mobile TV soon,

they are not longer against mobile TV since they

have experienced it as a handy medium to catch up

television content quickly. Innovators and early

adopters on the other hand were somehow

disappointed by the lack of interactive and

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

128

interesting content, resulting in their downgrade.

Despite the shift towards a more positive attitude,

the potential for mobile television remains

dramatically low, as the sample does not contain any

Innovators or Early Adopters anymore and that the

least innovative segments (Late Majority and

Laggards) remain largely overrepresented.

6 CONCLUSIONS

With this paper, we intended to reconcile two

opposing traditions: adoption diffusion and use

diffusion. Within the MADUF-project, we combined

research techniques from both traditions in an

interactionist way in order to get a more holistic

view on the possible success of mobile TV in

Flanders. By means of a PSAP-estimation, it became

clear that mobile TV is not ready yet for total market

acceptance so that a partial market or even niche

strategy was suggested. By means of a diary study,

combined with a pre-test and post-test survey during

a mobile TV-trial in a living lab environment, we

were able to get a better understanding of the

possible use diffusion of mobile TV. We found that

for most test persons traditional television remains

the reference point for evaluating mobile TV.

Television undoubtedly is one of the most

domesticated technologies within the home and

became so dominant that people often schedule their

behaviour in function of the TV-set. We found that

light and medium mobile viewers used the device at

home as a second TV with watching behaviour in

line with traditional TV. Heavy users on the contrary

watched mobile TV in a truly mobile and much

more complementary way with traditional television.

This resulted in mobile peak times coinciding with

regular TV for the former two groups, while for the

latter mobile TV allowed to extend the regular TV

viewing peak with two mobile peaks: one before and

after the regular peak. Finally, we witnessed the

(modest) overall positive effect of trialability

through a slightly increased general attitude towards

mobile TV during the field trial.

By combining these two paradigms, we were

able to draw a clearer picture of the potential success

of mobile TV and the different factors influencing

this success. While a quantitative potential

estimation can identify adoption segments and

describe them for targeting purposes, the qualitative

usage diffusion-research provides input for the fine-

tuning of the technology in terms of usage patterns,

features and content. We believe this methodological

plea for more interactionist research designs has

theoretical as well as industry and policy relevance

for the prediction of ICT user acceptance. For

instance, in the current debate of digital dividend

such predictions could help policymakers to get

insight in the feasibility of new communication

technologies and for which new technologies they

should preserve space in the future radio spectrum.

These estimations also allow marketing managers to

decide in which market segments they should invest

and with what offer these segments should be

targeted. Finally, for researchers we hope this paper

gives some food for thought about the added value

of an interactionist approach and inspires them to

work out more creative innovations research designs

in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The MADUF-project (Maximize DVB Usage in

Flanders) was supported by grants from the research

centre IBBT (Interdisciplinary Institute for

Broadband Technology) and a consortium of both

broadcasters and network solution companies. The

MADUF project aimed to maximize the social and

economic valorisation of DVB-H for the Flemish

citizen, government and industry (broadcasters,

operators and constructors) through the development

of a technological and regulatory consensus model

(pax mobilis).

REFERENCES

Boczkowski, P.J. (2004). The Mutual Shaping of

Technology and Society in Videotex Newspapers:

Beyond the Diffusion and Social Shaping

Perspectives. The Information Society, 20(4): 255-267.

Bouwman, H., Van Dijk, J., Van den Hooff, B. & van de

Wijngaert, L. (2002). ICT in organisaties. Adoptie,

implementatie, gebruik en effecten. Amsterdam:

Boom.

De Marez, L. (2006). Diffusie van ICT-innovaties:

accurater gebruikersinzicht voor betere introductie-

strategieën. Gent: Universiteit Gent.

De Marez, L., Verleye G, (2004). Innovation Diffusion:

the need for more accurate consumer insight.

Illustration of the PSAP-scale as a segmentation

instrument. The Journal of Targeting, Measurement

and Analysis for Marketing, 13(1): 32-49.

De Marez, L., Vyncke, P., Berte, K.; Schuurman, D. & De

Moor, K. (2008). Adopter segments, adoption

determinants and mobile marketing. Journal of

Targeting, Measurement & Analysis for Marketing,

16(1): 78-95.

ADOPTION VERSUS USE DIFFUSION - Predicting User Acceptance of Mobile TV in Flanders

129

Frissen V. (2000). ICTs in the rush hour of life.

Information Society, 16(1): 65-75.

Goldsmith, R.E. & Hofacker, C. (1991). Measuring

consumer innovativeness. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science 19(3): 209-222.

Jacobs, A.; Lievens, B.; Vangenck, M.; Vanhengel, E; &

Pierson, J. (2008). Mobile television or television on

mobile? In: A. Urban; B. Sapio & T. Turk (Eds.)

Digital Television Revisited. Linking Users, Markets

and Policies, 68-75.

Jankowski, N. & Van Selm, M. (2001). ICT en

samenleving. Vier terreinen voor empirisch

onderzoek. In: Bouwman, H. (Ed.), Communicatie in

de informatiesamenleving (p. 217-249). Utrecht:

Lemma.

Lievrouw, L. & Livingstone, S. (Eds) (2002). The

Handbook of New Media. London, Thousand Oaks,

New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Meade, N. & Islam, T. (2006). Modelling and forecasting

the diffusion of innovation. A 25-year review.

International Journal of Forecasting, 22: 519-545.

Moore, G.C. Benbasat, I. (1991). Development of an

instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an

information technology innovation. Information

Systems Research 2(3): 192-222.

Parasuraman, A. & Colby, C.L. (2001). Techno-reading

marketing: how and why your customers adopt

technology. New York: Free Press.

Punie, Y. (2000). Domesticatie van informatie- en

communicatietechnologie. Adoptie, gebruik en

betekenis van media in het dagelijkse leven: continue

beperking of discontinue bevrijding?. Vrije

Universiteit Brussel: Vakgroep

Communicatiewetenschappen.

Rogers, E.M. (1962). The diffusion of innovations. New

York: The Free Press.

Rogers, E.M. (2003), Diffusion of innovations (5

th

ed.),

New York: The Free Press.

Schuurman, D.; De Marez, L. & Evens, T. (2008). Mobile

TV: content is king, but who’s to be crowned?

Proceedings of International Technology, Education

and Development Conference. March 3-5, Valencia,

Spain.

Shih, C.-F. & Venkatesh, A. (2004). Beyond Adoption:

Development and Application of a Use-Diffusion

Model. Journal of Marketing, 68(January): 59-72.

Silverstone,R. & Haddon, L. (1996). Design and

domestication of information and communication

technologies: technical change and everyday life. In:

Silverstone, R. & Mansell, R (Eds.), Communication

by design. The politics of information and

communication technologies (p. 44-74). Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Trott, P. (2003). Innovation and Market Research. In:

Shavina, L.V. (Ed.), The International Handbook on

Innovation (p. 835-844). Oxford, UK: Pergamon,

Elsevier.

Van Den Broeck, W.; Pierson, J. & Pauwels, C. (2004).

Does interactive television imply new uses? A Flemish

case study, Conference Proceedings, Second European

Conference on Interactive Television. ‘Enhancing the

experience’, 31/03/2004-02/04/2004, University of

Brighton, UK: 101-112.

Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B. & Davis, F.D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technologies:

toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3): 425-478.

Verleye G., De Marez, L. (2005). Diffusion of

innovations: successful adoption needs more effective

soft-DSS driven targeting. The Journal of Targeting,

Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 13(2): 140-

155.

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

130