ENHANCED SECURE INTERFACE FOR A PORTABLE E-VOTING

TERMINAL

Andr´e Z´uquete

IEETA, University of Aveiro, Campus Univ. de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords:

e-voting, user interface, privacy, visual authentication, usability.

Abstract:

This paper presents an enhanced interface for an e-voting client application that partially runs inside a small,

portable terminal with reduced interaction capabilities. The interface was enhanced by cooperating with the

hosting computer where the terminal is connected to: the hosting computer shows a detailed image of the

filled ballot. The displayed image does not convey any personal information, namely the voter’s choices, to

the hosting computer; voter’s choices are solely presented at the terminal. Furthermore, the image contains

visual authentication elements that can be validated by the voter using information presented at the terminal.

This way, hosting computers are not able to gather voters’ choices or to deceive voters, by presenting tampered

ballots, without being noticed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Internet voting systems are appealing for several rea-

sons, one of them being the mobility of voters. Us-

ing the Internet, voters may contact the right electoral

servers virtually from anywhere in the world. How-

ever, the computers used by voters to express their

will must be trusted. Namely, they should not steal

authentication credentials, link votes to voters or in-

terfere destructively with the voting process. In other

words, voters should interact only with a trusted ap-

plication, running on top a secure platform – trusted

computing base, TCB – when expressing their vote.

However, this goal is hard to achieve. Nevertheless,

this “secure platform problem” is a fundamentalprob-

lem that needs to be solved when trying to design re-

mote electronic voting systems.

In the context of the Robust Electronic Voting Sys-

tem (REVS (Joaquim et al., 2003)) was developed

an intrusion-tolerant voting client using a TCB com-

posed by a FINREAD portable terminal and a smart-

card (Zquete et al., 2007). The terminal provides

protection against disclosure for user input (authen-

tication secrets, voter’s choices) and output (presenta-

tion of voter’s choices). Furthermore, it provides out-

put authentication for the presented ballot. With this

TCB, a voter may securely use any hosting computer

to access REVS electoral servers in order to vote in a

particular election. However, the line-based interface

of a FINREAD terminal is too reduced to give a clear,

global view of the ballot and the voter choices. This

issue is particularly relevant when ballots have many,

long questions, each with several possible answers.

This paper describes an enhancement of the in-

terface between the TCB and the voter to facilitate

voting processes. To enhance the interface, we ex-

tended the functionality of the voting terminal for co-

operating with a hosting computer in showing images

of ballots being filled. However, since we cannot

trust hosting computers for keeping secret the choices

expressed by voters, the images presented by host-

ing computers cannot contain any reference to voters’

choices. One way to achieve this goal could be to use

visual cryptography (M. and Shamir, 1995), but this

technique is not convenient for voters, raises many

operational problems and creates coercion vulnerabil-

ities. Alternatively, we used directly readable text for

helping voters to get a clear view of their choices, but

in such a way that no relevant, personal information

if leaked for hosting computers.

Furthermore, the presented image should be im-

mune to modifications introduced by hosting com-

puters, which requires their visual authentication by

voters. This means that either (i) the voter sees the

correct ballot or (ii) the voter sees a tampered image

but the tampering action is clearly perceptible by the

voter. The solution adopted allows the voter to re-

peatedly check the integrity of the displayed image

529

Zúquete A. (2008).

ENHANCED SECURE INTERFACE FOR A PORTABLE E-VOTING TERMINAL.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Cryptography, pages 529-537

DOI: 10.5220/0001922905290537

Copyright

c

SciTePress

using contents simultaneously presented on the ter-

minal display.

2 REVS VOTING SYSTEM

REVS is a blind-signature based voting system de-

signed for providing secure and robust electronic vot-

ing using the Internet (Joaquim et al., 2003). The sys-

tem has a client application (Voter Module) that con-

ducts the interaction with a set of electoral servers. To

improve the privacy of the voter and accuracy of his

participation in the election, the Voter Module should

use a TCB for protecting some critical data and voter-

computer interactions. Concerning the user interface,

the TCB must provide:

• Trusted output: correctly present to the voter au-

thenticated ballots provided by electoral servers.

• Protected input: securely get all input from the

voter – authentication secrets and ballot choices.

The TCB was implemented with a smartcard and

a FINREAD (FINREAD Consortium, 2003) reader,

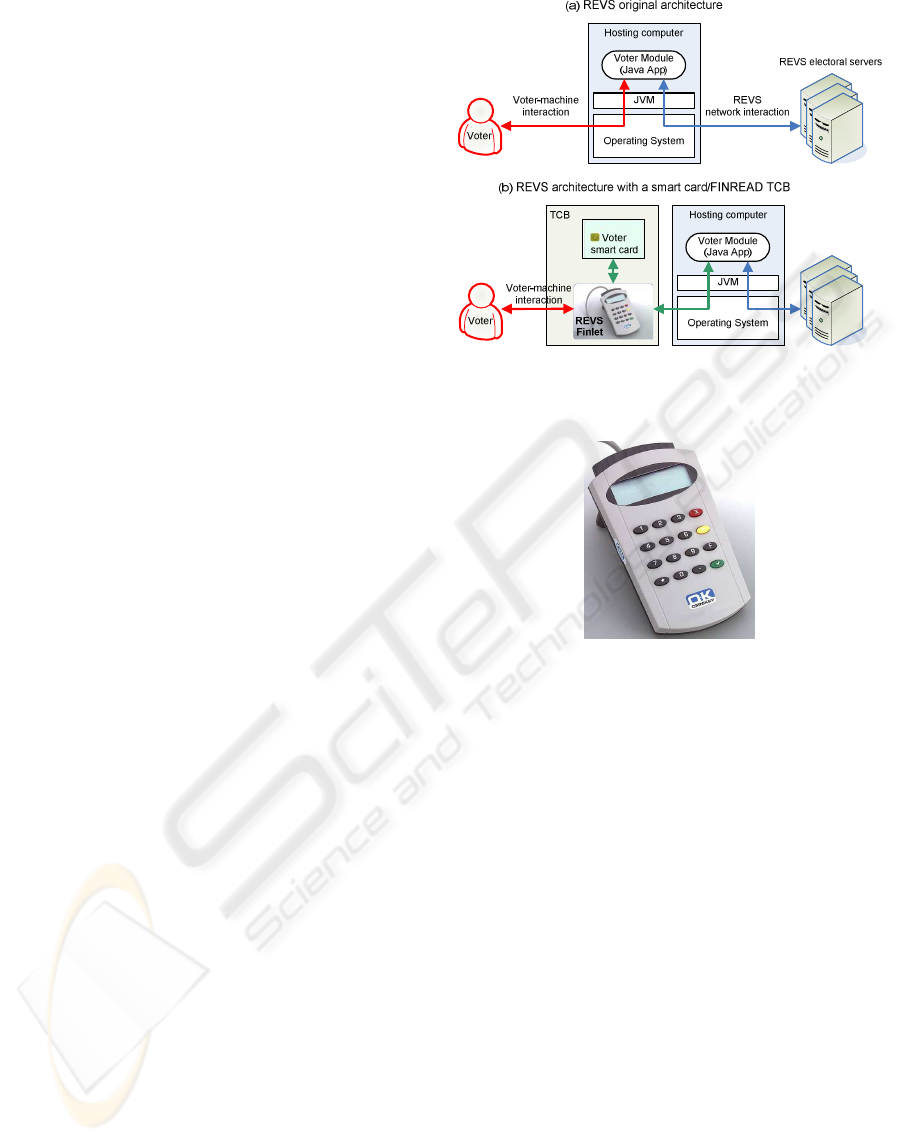

which has I/O capabilities (Zquete et al., 2007). Fig. 1

shows the new architecture of REVS using this TCB.

FINREAD terminals are embedded systems capable

of hosting different Java applets (Finlets) and a JVM

to execute them. A FINREAD device has reduced

human-machine I/O capabilities: it has a small LCD

display, with 4 lines of 20 characters, and a 16-key

pin-pad (see Fig. 2). Finlets control all interactions

with the smartcard and can use the terminal I/O ca-

pabilities to perform protected input/output with the

terminal user (e.g. get the smartcard PIN).

One of the tasks of the Voter Module Finlet is to

deal with the interface with voter, namely with the

presentation and filling of ballots. Ballots are signed

XML documents fetched from electoral servers and

validated by voters using their smartcard. If valid, a

ballot is presented and filled using the FINREAD dis-

play and pin-pad. The part of the Voter Module that

runs in the hosting computer has no direct influence

in the presentation and filling of the ballot.

2.1 FINREAD Human Interface Issues

Due to the FINREAD display limitations, the pre-

sentation of the ballot in this device was completely

changed from the original REVS model. Further-

more, the ballots’ text to present to voters must

be produced differently by the electoral Authorities,

namely using reduced amounts of text in questions

an answers taking into consideration the reduced ca-

pabilities of a FINREAD display. Nevertheless, the

Figure 1: Evolution in the architecture of REVS for sup-

porting a smartcard/FINREAD TCB at the voter side.

Figure 2: FINREAD terminal from Omnikey.

FINREAD display is too reduced for having a clear

and complete view of the ballot and voter’s choices.

This limitation can be a major constraint when filing

long ballots, with many questions and answers.

To overcome the physical output limitations of the

FINREAD terminal we considered a solution based

on cooperating with the hosting computer: the termi-

nal produces an image of the filled ballot and sends it

to the Voter Module for being displayed at the hosting

computer. But for producing these images we have

two critical requirements:

• The displayed image should not disclose any use-

ful information to others than the voter.

• The displayed image should allow the voter to

easily detect tampering actions performed by the

Voter Module and/or the hosting computer.

The first requirement is critical for the confidential-

ity of voters choices. Otherwise, a malicious hosting

computer (or Voter Module) could store the images

of the ballots presented with voters’ choices. Further-

more, images should not enable attackers to coerce

voters to prove how they have voted.

The second requirement is critical for prevent-

SECRYPT 2008 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

530

ing a malicious hosting computer from presenting a

tampered ballot, which could mislead voters in many

ways by (i) modifying questions, (ii) changing possi-

ble answers or (iii) changing chosen answers.

In the next section we discuss related work re-

garding the secure presentation of contents (images)

produced by our TCB. Afterwards, we describe some

usability issues of voting systems are their impact in

our system. Then, we describe our contribution to en-

hance the interface of the voting terminal.

3 RELATED WORK

Visual cryptography (M. and Shamir, 1995) allows

humans to decrypt an image using another image,

printed in a transparency. The encrypted image is pre-

sented in the screen, or printed in a sheet of paper, and

the decryption transparency, a slide with a painted de-

cryption pattern, must be placed on top of it to turn

an area filled with apparently random dots into some-

thing understandable by a human. Visual cryptogra-

phy can also be used for content integrity; (Naor and

Pinkas, 1997) discusses several visual authentication

methods, using visual cryptography, for any kind of

visual data: numerical, textual or graphical.

Visual cryptography could be used for ensuring

the privacy and integrity control of the ballot im-

ages presented by hosting computers; the key to en-

crypt the image could be entered with the FINREAD

pin-pad. However, decryption transparencies are not

convenient for voters, which already have to carry

a smartcard and a reader, a single decryption trans-

parency is not likely to be a ubiquitous solution, since

it may not work well with all displays, and keys and

transparencies make voters vulnerable to coercion.

(Gobioff et al., 1996) discusses minimal proper-

ties necessary for secure input or output of a smart-

card in a point-of-sale (POS); a POS is comparable to

our hosting computer but using an ordinary smartcard

reader without human I/O capabilities. They discuss

additional I/O capabilities that smartcards could have

and how they could be used to address security prob-

lems raised by hostile POS environments. The aspects

more relevant for our work are, using their terminol-

ogy, privacy of the output and general trusted output.

Privacy of the output is addressed with one-time

pad encryption, using a key provided by the smart-

card owner using a smartcard input keyboard. How-

ever, the decryption of the encrypted output is not

addressed, nor even who is going to do so; in our

case we could consider visual decryption by the voter

using a personal decryption transparency. General

trusted output is addressed with trusted input and one

bit of trusted output. The method relies on feedback:

every output bit is feed back into the smartcard, using

the trusted input, and when an error is detected the

trusted output bit displays the error condition. In our

case a feedback mechanism is possible, but not with

the bits of the displayed image. As we will see, we

used characters.

Completely Automated Public Turing Tests to Tell

Computers and Humans Apart (CAPTCHA (von Ahn

et al., 2003)) are ways of transforming text into an

image such that only humans can understand it. At-

tacking computer programs are unable to extract the

text from the image due to the properties of the trans-

formation – a hard artificial intelligence (AI) transfor-

mation (a problem can be solved by a majority of hu-

mans but not by a computer using state-of-the-art AI

programs). Consequently, attacking computers also

havedifficulty to makea useful but undetectable mod-

ification to the text within the image. Thus, if the text

contains some visual authentication element, it may

be used to check the integrity of the image. However,

CAPTCHAs are some times hard to understand even

by humans and are used to transform single words or

small sentences, not long texts, such as electoral bal-

lots. Furthermore, attacking computers may use back-

end pools of people to interpret CAPTCHAs.

(King and dos Santos, 2005) extends CAPTCHA

by introducing keyed AI transformations. These ex-

tend text→image transformations like CAPTCHA to

include a secret shared between the image producer

and the authenticator. This way, attacking computers

cannot replace entire images based on public contents

(e.g. electoral ballots). The examples, however, are

with simple, short sentences, and not with long texts,

such as electoral ballots.

(Hanley et al., 2005) proposed an e-voting system

based on keyed AI transformations. Voters get ballots

transformed by CAPTCHAs and should be able to un-

derstand them and to make a choice by pointing out

a particular section of the ballot (an area of an image,

a frame of a film, etc.). The selected section is ran-

domly mapped per voter to a particular answer. Un-

fortunately, the system has many security problems:

the recording of presented ballots and choices made

by voters may undermine their privacy and ballots are

not authenticated.

4 VOTING USABILITY ISSUES

Voting processes raise several usability issues for sev-

eral reasons (Bederson et al., 2003; Greene et al.,

2006; Byrne et al., 2007). First, they are to be used

by people with different abilities, such as language

ENHANCED SECURE INTERFACE FOR A PORTABLE E-VOTING TERMINAL

531

understanding, different impairments, such as blind-

ness, etc. In short, the population they are targeted to

is very heterogeneous in many aspects, but the system

should not disfranchise any voter because of their dif-

ference. This means that the usability of voting sys-

tems must be very carefully evaluated to detect and

eliminate their disfranchising potentials.

Second, usually voters are not trained to use spe-

cific voting devices. Many voters effectively deal with

voting devices the first time they have to use them in

real elections. This may create many usability prob-

lems, which are amplified by the reluctance of asking

for help (because of privacy concerns), the pressure

of long waiting queues, etc.

Its now time to comment our proposal regarding

usability issues. First, we are not proposing a per-

fect voting terminal for being used by everybodyin all

elections. We are proposingan enhanced, visual inter-

face for a portable, voting terminal. The advantage of

using the terminal is that voters may potentially vote

anywhere, but that is not mandatory, only possible.

Therefore, we do not advocate the use of this terminal

for all voters, but only for those willing to get some

advantage out of it (such as mobility). And, of course,

we assume they can read the ballot’s text.

Second, this paper presents only one possible in-

terface for the portable terminal, using text. Further-

more, the interface uses images and colors for text

authentication, which is not suitable for blind peo-

ple and creates problems to people with visual im-

pairments, such as color blindness. However, other

interfaces may be addressed in the future for helping

people with difficulties in using this one (using pic-

tures, audio, braille output interfaces, etc.).

Third, a portable, personal voting terminal allows

voters to get used to it, to learn very well how it works

and to customize its behaviour in order to facilitate the

participation in elections. Therefore, in our work it is

relevant to discuss several interface possibilities and

their pros and cons, and configuration options, instead

of proving a single, inflexible and well-studied inter-

face. This thus not mean that we do not need to carry

on a detailed usability study with real voters in real-

istic elections. However, unlike other voting systems,

customization is relevant and should be considered in

the interface proposal and also in the training of vot-

ers, something that was not considered in (Bederson

et al., 2003; Byrne et al., 2007).

Finally, in the interface here presented we deal

with the visual authentication of ballot contents. As

far as we know, no voting system until now did that;

voters assume the system provides them the right bal-

lot, and not a false one. Visual authentication is a task

that is natural to increase the cognitive workload of

voters, therefore making even more difficult to evalu-

ate the usability of the system. In this document we

anticipate some cognitive workload problems, some

of them detected with practical experience with users,

and we draw some possible solutions to deal we them.

Again, our goal was to provide flexibility to the con-

figuration of the interface in order to better adapt it to

the terminal owner. Nevertheless, we assume that vot-

ers willing to use this interface for some reason (such

as mobility) are aware and comfortable with the extra

workload it may introduce in voting processes.

5 ENHANCED INTERFACE

We will now present our contribution, a solution for

improving the interface of the FINREAD voting ter-

minal without reducing its security. First we describe

how filled ballots are presented to voters using the dis-

play of hosting computers but without disclosing vot-

ers’ choices. Next we discuss alternatives for enforc-

ing the integrity control of the presented ballot and we

present our preferred solutions.

5.1 Non-disclosure of Voters’ Choices

The presentation of filled ballots without disclosing

voters’ choices forced us to look for some way to

represent a filled ballot other than traditional ones

(e.g. with crosses inside boxes or completed arrows).

We used the fact of having two separate displays – the

terminal display and the display of the hosting com-

puter – to present complementary contents conveying

useful information to the voter only. Naturally, the se-

curity of this approach requires that attackers cannot

monitor both displays simultaneously.

The link between the information presented in

each display is done with numbers. Each possible an-

swer to a question is given a number (hardcoded in

the ballot XML or dynamically given by the termi-

nal). When a question and its possible answers are

displayed at the hosting computer, the numbers are

displayed as well. Simultaneously, on the terminal

display are presented only the numbers corresponding

to the answers chosen by the voter for that question.

For clarification, here is an example. Let’s assume

that a question in the ballot has 3 alternatives: YES,

NO or none of them (blank), numbered from 0 to 2 (0

for blank). If the voter chooses option NO, the image

presented on the screen and the information presented

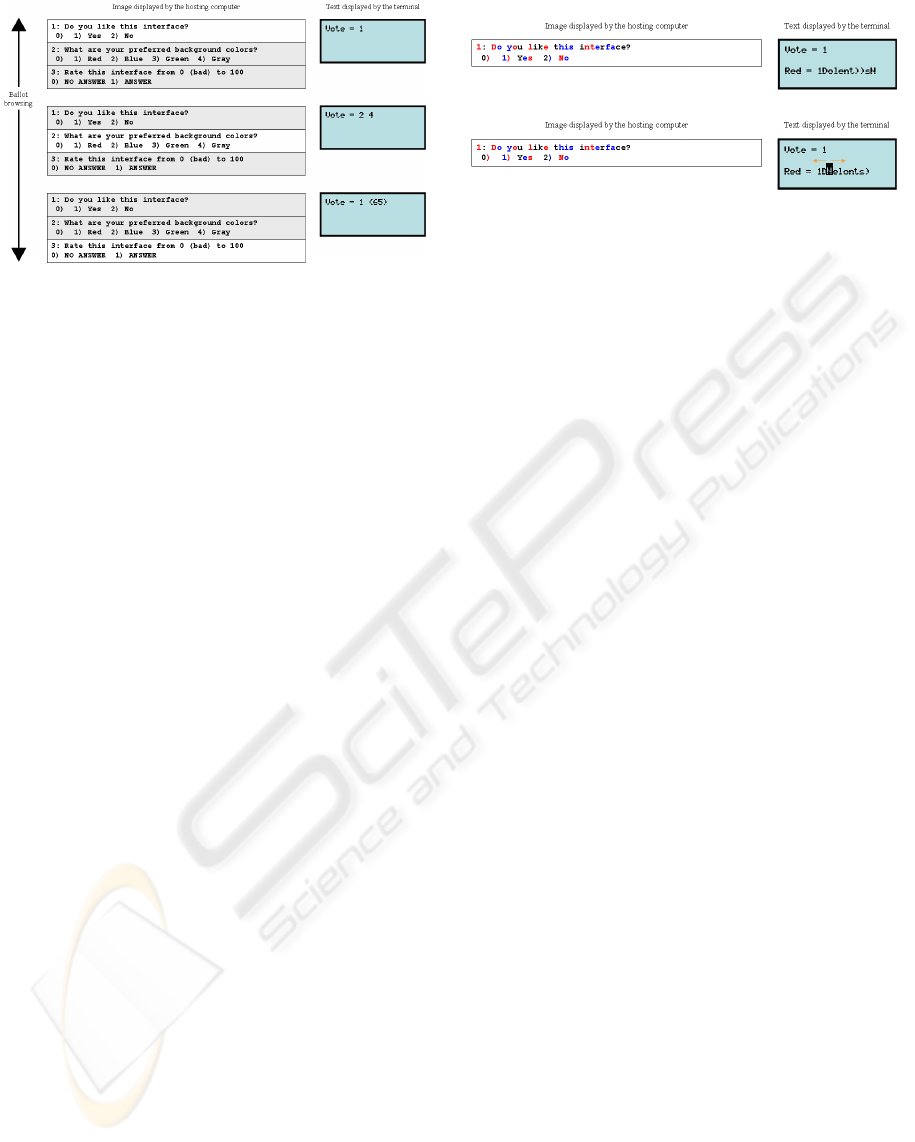

on the terminal will look like shown in Fig. 3.

Multiple choices may be expressed using the same

model, requiring only displaying on the terminal more

than one number. Considering the question presented

SECRYPT 2008 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

532

in Fig. 4, where the voter can choose up to four an-

swers (Cat, Fish, Dog and Bird), the number of all the

chosen ones is presented in the terminal.

For questions with many possible answers, for in-

stance, a number between 0 and 100, the solution is

different (see Fig. 5). In this case the image pre-

sented by the hosting computer will only contains two

choices, one for a blank vote (NO ANSWER) and an-

other for an expressed vote (ANSWER), and the ter-

minal refers the chosen one; but for an expressed vote

it will also display the answer (18 in Fig. 5-b).

The voting interface for the voter works like this.

The hosting computer displays an image of the bal-

lot containing the current question and the remaining

questions that fit in the allocated image space; cur-

rent question and answers are highlighted (see Fig. 6).

The voter reads the current question and chooses one

or many answers using the terminal pin-pad. The an-

swers are shown in the terminal as they are expressed;

at the end the voter uses a function key of the pin-pad

(we used the green key) to confirm the choices and

proceed to the next question.

For questions with a single answer from a large set

of possible values (as in Fig. 5), the voter first chooses

0 or 1 with the pin-pad, for choosing between a blank

vote and an expressed vote. Then, if she chose 1, she

enters a specific answer using the pin-pad. Finally,

she confirms the answer, using the confirmation key

of the terminal, or repeats the process.

Before committing to the vote with a function key

of the pin-pad (we used the yellow key), the voter can

browse through the questions, which are highlighted

at the hosting computer display, and check the corre-

sponding answers on the terminal display. Browsing

up and down is performed with a pair of pin-pad func-

tion keys (we used keys ’*’ and ’.’). The voter is also

able to delete answers, with another function key (we

used the red key), while filling the ballot or review-

ing her answers. We believe that this reduced set of

functionalities is enough for providing a simple and

efective browsing through ballot questions and filling

and reviewing of chosen answers.

5.2 Authentication of Displayed Ballots

Electoral ballots are usually public; therefore attack-

ers may use their information to interfere with the

displaying of ballots in tampered hosting computers.

Therefore, voters using the terminal must use some

mechanism to ensure that the image displayed by the

hosting computer was generated by the terminal from

a correct XML document.

The integrity of the XML document is assured by

digital signatures; the XML is signed by an electoral

Tradicional vote

Are you a regular voter?

2 YES 4 NO

Vote with FINREAD terminal and hosting computer

Terminal

Vote = 2

Computer

Are you a regular voter?

screen

0) 1) YES 2) NO

Figure 3: Voting with a single answer per question (voter

chose NO). With the terminal the voter entered 2 for NO.

Tradicional vote

Preferred domestic animals?

4 Cat 2 Fish 4 Dog 2 Bird

Vote with FINREAD terminal and hosting computer

Terminal

Vote = 1 3

Computer

Preferred domestic animals?

screen

0) 1) Cat 2) Fish 3) Dog 4) Bird

Figure 4: Voting with several answers per question (voter

chose Cat and Dog). With the terminal the voter entered 1

and 3 for Cat and Dog, respectively.

(a)

Tradicional vote

Best year of your life (0-100)?

Vote with FINREAD terminal and hosting computer

Terminal

Vote = 0 (blank)

Computer

Best year of your life (0-100)?

screen

0) NO ANSWER 1) ANSWER

(b)

Tradicional vote

Best year of your life (0-100)? 18

Vote with FINREAD terminal and hosting computer

Terminal

Vote = 1 (18)

Computer

Best year of your life (0-100)?

screen

0) NO ANSWER 1) ANSWER

Figure 5: Voting with a single answer from a large set of

possible answers per question. In (a) the voter did not vote

and in (b) the voter chose 18. With the terminal the voter

entered 0 for a blank vote (a) and 1 and a number for an

expressed vote (b).

Authority and the signature validated by the terminal

using the Authority’s public key stored inside voters’

smartcards (Zquete et al., 2007). The integrity con-

trol of the ballot image is more complex, as it needs

to be performed by the voter. This may be accom-

plished using visual authentication, where the voter,

using observation and some helping technology, can

ensure that the displayed image if fresh and correct.

To produce visually authenticated images with the

terminal we can use voter-provided keys: the voter

introduces a key using the terminal pin-pad, and the

terminal uses it to authenticate the image. This key

may be a long-term key used for visual cryptography

or a fresh, random key for a keyed AI transformation.

ENHANCED SECURE INTERFACE FOR A PORTABLE E-VOTING TERMINAL

533

Figure 6: Ballot filling interface. On the left is the image

presented by the hosting computer, which changes along

the filling process and highlights the current question and

all its possible answers. On the right is the text presented

by the terminal — the answers to the current question.

Another alternative is to use feedback: the termi-

nal produces an image with highlighted, randomly se-

lected characters belonging to the ballot text, which

should be feed back in the correct order to the ter-

minal using its pin-pad (

active validation

). However,

for pin-pads such as the one of the FINREAD termi-

nal, which only contains numbers and a few func-

tion keys (cf. Fig 2), the introduction of alphabeti-

cal characters is not straightforward. One alternative

is to map several characters to each key, as in mobile

phones; another alternative is to show all the feedback

characters, without repetitions and in a different order

(e.g. alphabetically) in the terminal display and use

the pin-pad to navigate through them and to select the

observed highlighted characters in the correct order.

Yet another alternative is to let the terminal to

randomly choose keys or feedback characters and to

show them using its display. This way, the voter only

needs to check if the data displayed by the terminal

matches the authentication data existing in the pre-

sented image (passive validation).

Hereafter we will describe a solution using feed-

back characters with active or passive user validation.

For each question the terminal chooses a random set

of feedback characters from the question and its an-

swers. The feedback characters are then written in the

image with some differentiating characteristic, such

as a different colour or letter case. The voter iden-

tifies the feedback characters in the image and val-

idates them using active or passive validation. For

differentiating feedback characters in the images we

used colours. Colours, or at least a small set of basic

colours, are easy to identify and differentiate by most

people, except colour-blind people.

A simple way to use colours to identify feedback

characters is the following. First the terminal ran-

domly chooses a highlight colour from a list of basic

(a) Passive validation of a feedback string

(b) Active validation of a feedback string

Figure 7: Visual authentication of displayed questions and

answers with colours and a feedback string for (a) passive

validation or (b) active validation; the terminal is using red

for highlighting feedback characters. With passive valida-

tion, the voter checks if the feedback string matches the red

characters of the image in the correct order. With active val-

idation, the voter chooses, by navigating with the terminal

pin-pad on the alphabetically ordered feedback string, the

red characters in the correct order.

colours (red, green, blue, yellow, white, black, etc.).

The terminal will then compose the text in the im-

age using the highlight colour for the feedback char-

acters and random colours, from the rest of the colour

list, for the other characters (see example in Fig. 7).

A malicious hosting computer cannot conclude, from

the text colours, which are the feedback characters;

thus, producing a tampered image for a question and

its answers has a probability of success that depends

on guessing the actual highlighting colour.

For tampering an image without being noticed, an

attacker must guess the highlight colour, identify all

the highlighted characters of each image and produce

a different, meaningful question and answers using

the same ordered set of highlighted characters. Fig-

ure 8 shows two different tampered images that can

replace the image presented in Fig. 7 and 8-a: image

(b) has a different order in the answers and is correctly

authenticated if the highlight colours are red or black;

image (c) has a different question and is correctly au-

thenticated if the highlight colour is blue.

Assuming that it is feasible to create a convincing

tampered image for any highlight colour, the success

of a tampering attack basically depends on the num-

ber of colours used and on the possibility of creating

a single tampered image for more than one colour (as

in Fig. 8-b). Thus, using more colours reduces both

the probability of guessing the actual highlight colour

and the length of the feedback string presented in the

voting terminal, improving usability.

On the other hand, the number of colours used and

its distribution along the question and answers is also

critical to the process of building a convincing tam-

pered image. For instance, using only two colours

and alternating them on consecutivecharacters clearly

complicates the task of the attacker for building a con-

vincing image. However, the fewer colours are used,

SECRYPT 2008 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

534

(a) Original image built with highlight colour red

(b) Tampered answers for red and black highlight colours

(c) Tampered question for the blue highlight colour

Figure 8: Original image and tampered images that may be

considered valid by the voter.

the longer is the feedback string displayed in the vot-

ing terminal. Concluding, we have different argu-

ments for using a few or many colours.

A compromise solution is the following. Assum-

ing that there are N possible colours, all of them are

used and the terminal chooses 2 highlight colours, one

for the question and the other for the answers, pos-

sibly the same. For colouring the characters, all N

colours are used in blocks of contiguous N characters,

but not always with the same order.

With this approach we reduce the probability

of correctly guessing the actual highlighting colours

from

1

N

to

1

N

2

without significantly complicating the

user interface. Since at least one feedback charac-

ter appears in each N-character block, attackers ex-

perience tampering constraints along the entire text.

Nevertheless, an attacker may precompute all possi-

ble alternative images for any set of highlight colours,

which are N

L/N

images, where L is the number of

characters in the original image, and chose the appro-

priate one with the guessed highlighting colour pair.

Figure 9 shows an implementation of this authen-

tication strategy using only 4 possible colours (RGB

plus black) and two highlight colours, thus N = 4.

The two feedback strings are short, with 6 and 5 char-

acters each, being easy to check. The probability of

guessing the actual pair of feedback colours is

1

16

and

the number of colouring alternatives is 4

42/4

≈ 10

6

,

which is high enough for complicating the task of pre-

computing all possible, convincing tampered images.

6 ANALYSIS

6.1 Voter Privacy

If an attacker could monitor the voting terminal of

a voter then it could get all the voter’s options, de-

stroying this way his privacy. Thus, a fundamental

requirement for using correctly the voting terminal is

to prevent anyone from monitoring its input interface

– the pin-pad. Since the pin-pad is close to the dis-

play lines, we can also assume that attackers cannot

Figure 9: Improved visual authentication of questions and

answers with 2 highlight colours (red and black) out of 4

and passive validation of feedback strings.

monitor the terminal display.

Assuming that attackers cannot monitor the termi-

nal interface, then it’s straightforward proving that at-

tackers controlling hosting computers cannot get any

useful information: displayed ballots have no voters’

choices and feedback characters are randomly chosen

by terminals. Displayed images gathered by attack-

ers cannot also be used latter to coerce voters to prove

how they have voted, because images do not contain

any personal information.

6.2 Image Authentication

The tampering of displayed images is possible, but

the probability of success is small, though not ne-

glectable. This probability depends on two factors:

(i) guessing the right set of highlight colours and (ii)

producing a convincing image while keeping the or-

dered sets of highlighted characters. These tasks can

be made arbitrarily hard by using high values for the

total number of colours (N) and the number of high-

light colours (H), but that has also impact on usability.

Namely, using high values for N is inconvenient be-

cause colours become complex to describe in the ter-

minal (e.g. medium spring green) and hard to match

on the displayed image; this last issue is particularly

relevant for colour-blind people. Using high values

for H is also inconvenient, has it floods the terminal

display with feedback strings, ultimately displaying

the majority of the characters in the question and an-

swers but in a mangled fashion. Therefore, for usabil-

ity we should keep N and H as low as possible.

An alternative for reducing the probability of suc-

cess of a tampering attack is to enable a voter to check

on the terminal feedback strings for different colours,

but not all at the same time. For instance, if the first

presented strings are for red and black, the nextstrings

may use other combinations of colours, like red and

green, blue and green, etc. The continuous valida-

tion should be triggered by the voter, using a terminal

key (we used the key ’F’), and the image displayed

should always be the same. The voter may stop at any

time for authenticating the displayed image against

the feedback strings currently presented on the termi-

nal. This repeated authentication is easy to implement

and enables voters to make the authentication mecha-

nism as strong as personally required: the more feed-

ENHANCED SECURE INTERFACE FOR A PORTABLE E-VOTING TERMINAL

535

back strings are checked, the higher is the probability

of detecting a tampered image.

Colour-blindness raises obvious usability problems

for the proposed visual authentication mechanism us-

ing colour-based feedback. Allowing voters to con-

tinuously change the feedback strings may partially

solve the problem for people with limited colour-

blindness, as they may change the set of feedback

strings until being able to clearly distinguish the two

highlighting colours used in the feedback strings.

However, for people that only see black and white it

simply should not work; for those people another vi-

sual authentication mechanism must be used.

6.3 Feedback Validation

We referred two possible policies that can be used to

visually authenticate images using feedback charac-

ters — passive validation or active validation. With

passive validation, voters mentally check the high-

lighted characters against the feedback string and con-

clude if the image is genuine or a fraud. On the con-

trary, with active validation, voters have to use the

pin-pad to input the highlighted characters and the ter-

minal checks them against the feedback strings.

Passive validation is more convenientfor users but

also more prone to human errors. Careless voters may

proceed with the voting without properly authenticat-

ing the images or even proceed after detecting many

consecutive display errors. Furthermore, voters must

be conscious about error management, i.e., if a voter

gets 6 errors in 7 authentication attempts, then there

is an obvious problem with the displayed images and

the voter should not further consider them in the cur-

rent voting process. If, on the contrary, the voter gets

1 error in the same 7 attempts, then probably the er-

ror was caused by an occasional misinterpretation of

feedback elements.

Active is less convenient to voters but is more se-

cure, because voters can not proceed without properly

authenticating the image. But some escape mecha-

nism should exist to prevent denial of service attacks

by hosting computers or visual problems with voters;

for instance, after a limited sequence of authentication

errors the terminal should abandon the presentation of

images and use only its small display to show contents

to the voter. Active feedback is also less convenient

for consecutive authentication with different colours.

This means that voters may tend to minimize the in-

put feedback to proceed with the voting process, thus

reducing the overall authentication strength.

Concluding, both policies have pros and cons: for

voter convenience we should go for passive valida-

tion, for voter security we should go for active vali-

dation. We expect that usability tests may introduce

some bias towards each of these policies.

6.4 Preliminary Usability Experiences

For evaluating the usability of this voting interface

with many people we developed a Java applet demon-

strator

1

. This demonstrator contains a replica of the

FINREAD terminal and the image presented by the

hosting computer and implements only passive feed-

back. Furthermore, it allows voters to choose the set

of colours used for painting the actual question and its

answers. This dynamic colour palette enables voters

to learn the set of colours they feel comfortable with,

in order to ultimately customize their smartcard for

controlling their FINREAD terminal.

Preliminary experiences showed that scattered

colouring of isolated letters introduces a very high

cognitive load in the authentication task. Further-

more, long questions or many answers require many

colours, because feedback strings have a limited

length, which further complicates the location of the

feedback characters.

A solution for this problem is aggregation of char-

acters with the same colour. Aggregation facilitates

significantly the location of the coloured characters

being used in the authentication process, because the

text to authenticate becomes coloured by “areas”.

Furthermore, aggregation improves the readability of

text when using many different colours The demon-

strator allows voters to change the level of aggrega-

tion to evaluate its impact in the cognitive load in-

volved in ballot authentication operations

Changing the colour associated with the feedback

string, without changing the image presented by the

hosting computer, enables the voter to validate as

many “areas” of the presented question and answers

as she feels required, in order to increase her confi-

dence in the authentication. High aggregation levels

and short questions, or sets of answers, such as yes/no

answers, may even produce feedback strings with all

the text to authenticate.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we described a proposal for enhancing

the interface of an FINREAD-based, portable vot-

ing terminal. This interface presents ballot images in

the hosting computer display, but prevents the host-

ing computer to violate the voter privacy or to deceive

him with fake images without being noticed.

1

http://www.ieeta.pt/˜avz/FINREAD

SECRYPT 2008 - International Conference on Security and Cryptography

536

The design of the enhanced interface relies on the

fact that voters have two different displays: one pro-

tected, on the terminal, and another insecure one, pro-

vided by the hosting computer. The terminal dis-

play showssmall amountsof informationallowing the

voter to check his answers and verify the correctness

of the presented image. For verifying the correctness

of the image a different kind of visual authentication

is used, based on random, coloured feedback charac-

ters. Even with a small number of colours it is possi-

ble to reduce to acceptable levels the probability of

deceiving a voter with tampered images. Anyway,

this (small) probability can be arbitrary reduced by

allowing the voter to require many different, consec-

utive visual authentications for each image.

The implementation of this enhanced interface is

in the beginning. First we will use the demonstrator

to conduct usability tests in order to evaluate its prob-

lems and limitations. For this purpose, we plan to

improve the demonstrator to handle either passive or

active feedback and to introduce errors in the image

presented in the hosting computer. Only afterwards

we will add it to the current REVS TCB, using the

FINREAD terminal.

REFERENCES

Bederson, B. B., Lee, B., Sherman, R. M., Herrnson, P. S.,

and Niemi, R. G. (2003). Electronic voting system

usability issues. In Proc. of the SIGCHI Conf. on Hu-

man Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’03), pages

145–152, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA. ACM.

Byrne, M. D., Greene, K. K., and Everett, S. P. (2007).

Usability of voting systems: baseline data for paper,

punch cards, and lever machines. In Proc. of the ACM

SIGCHI Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Sys-

tems (CHI’07), pages 171–180, San Jose, CA, USA.

FINREAD Consortium(2003). FINREAD Technical Spec-

ifications, Parts 1-8.

Gobioff, H., Smith, S., Tygar, J. D., and Yee, B. (1996).

Smart Cards in Hostile Environments. In 2nd USENIX

Works. on Electronic Commerce, Oakland, USA.

Greene, K. K., Byrne, M. D., and Everett, S. P. (2006). A

comparison of usability between voting methods. In

Proc. of the 2006 USENIX/Accurate Electronic Vot-

ing Technology Works., pages 2–2, Vancouver, B.C.,

Canada. USENIX Association.

Hanley, D., King, J., and dos Santos, A. (2005). Defeating

Malicious Terminals in an Electronic Voting System.

In Proc. of 5th Brazilian Symp. on Information and

Computer System Security (SBSeg 2005), Florianpo-

lis, SC, Brazil.

Joaquim, R., Zquete, A., and Ferreira, P. (2003). REVS – A

Robust Electronic Voting System. IADIS Int. Journal

of WWW/Internet, 1(2).

King, J. and dos Santos, A. (2005). A User-Friendly Ap-

proach to Human Authentication of Messages. In Fi-

nancial Cryptogr. and Data Security. LNCS 3570.

M., M. N. and Shamir, A. (1995). Visual Cryptography. In

Eurocrypt ’94. Springer-Verlag. LNCS 950.

Naor, M. and Pinkas, B. (1997). Visual Authentication and

Identification. In Advances in Cryptology – Crypto 97

Proc. Springer-Verlag. LNCS 1294.

von Ahn, L., Blum, M., Hopper, N. J., and Langford, J.

(2003). CAPTCHA: Using Hard AI Problems For Se-

curity. In Adv. in Cryptology – Eurocrypt 2003 Proc.

Springer-Verlag. LNCS 2656.

Zquete, A., Costa, C., and Romo, M. (2007). An Intrusion-

Tolerant e-Voting Client System. In 1st Works.

on Recent Advances on Intrusion-Tolerant Systems

(WRAITS 2007), Lisboa, Portugal.

ENHANCED SECURE INTERFACE FOR A PORTABLE E-VOTING TERMINAL

537