CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON INFORMATICS?

A Comparison of Three National Electronic Health Records

Bettine Pluut

Utrecht School of Governance, Utrecht University, Bijlhouwerstraat 6, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Zenc consultancy, Alexanderstraat 18, The Hague, The Netherlands

Arre Zuurmond

Faculty of Technology, Policy and management, Technical University, Jaffalaan 5, Delft, The Netherlands

Zenc Consultancy, Alexanderstraat 18, The Hague, The Netherlands

Keywords: Electronic Health Records, Health informatics, Relational Responsibility, Doctor-patient relationship.

Abstract: Participatory approaches to health care are getting increasingly popular in Western countries. But are the

perspectives on informatics changing as well? Because not every patient (always) can or wants to actively

participate in his health care process, differentiation in medical encounters is needed. We use the term

‘relational responsibility’ to refer to a process in which doctor and patient are responsive to each other’s

norms, values and ideas, especially with respect to their role division. Health informatics can support or

restrict this differentiation by giving patients access to Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and/or converging

those records with Personal Health Records (consumer oriented informatics). When we look at the policies

on the national EHRs in Canada, Denmark, and The Netherlands we find that the orientation towards

informatics is still mainly provider-oriented. Even when policy makers emphasize the importance of patient

participation and are aware of the potential of health informatics in this context, they have not given priority

to translating this into the design of their EHR. This means that for the upcoming years EHRs will support

one traditional role division: the one in which the health care professional is in the lead and is the better-

informed party.

1 INTRODUCTION

There appears to be a worldwide trend towards the

development of Electronic Health Records (EHRs).

On all continents nationwide generic Electronic

Health Records are being introduced (see e.g.

EHTEL, 2008). In addition, there is a trend towards

health records that are more directed towards use by

patients – the so-called Personal Health Records

(Tang et al., 2006).

Electronic Health Records are not ‘just’ a

technical matter. On the contrary, they can be seen

as the ‘stabilization’ (Chia, 1996) of norms, values

and conceptions of ‘good health care’. Ideas of a

‘good’ division of roles between doctor and patient

are automated and thus stabilized in EHRs.

Analyzing the stabilization of such norms and

values in EHRs is timely because of the increasing

popularity of participatory approaches to health care

(Todres et al, 2007). An explanation for this

popularity is that patient participation is considered

‘ethical’ (see e.g. Stilgoe and Farook, 2008). Patients

tend to be more satisfied when they have an active

role in considering and deciding about possible

treatments. Sometimes this also leads to better health

results (Jahng et al., 2005). The second argument for

patient participation lies in the demographic and

labour market developments in many western

countries (see e.g., Commission of the European

Communities, 2000). Because of an ageing

population it is argued that a significant amount of

health care tasks need to be carried out by patients

and/or their family members (Van den Eerenbeemt

and Mulder, 2005).

Still patient participation can also be ‘unethical’.

For instance, patients can be emotionally and

mentally unable or unwilling to decide about their

treatments (Bensing et al., 2004). Moreover, the

extent to which patients appreciate an egalitarian

416

Pluut B. and Zuurmond A. (2009).

CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON INFORMATICS? - A Comparison of Three National Electronic Health Records.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 416-420

DOI: 10.5220/0001431004160420

Copyright

c

SciTePress

relationship with a health care professional varies

from patient to patient and from context to context

(Bensing et al, 2004).

This implies that within every medical encounter

doctor and patient face the challenge of distributing

roles and responsibilities, depending on the specific

context. We use the term ‘Relational Responsibility’

to refer to a process by which doctor and patient are

responsive to each other’s ideas, norms and values

and thus try to create an optimal role division,

depending on the specific context of their

interactions (McNamee and Gergen, 1999). So for

instance, sometimes patient and doctor both agree to

a subject-object understanding of their relationship,

in which the patient has a passive role. At other

times, the patient will appreciate an active

participant in his health care situation. This asks of

the participants in doctor-patient communication to

be open to each other’s preferences. In this way a so-

called ‘soft’ self-other differentiation can emerge

(Hosking, 2007).

2 CHANGING INFORMATICS

So far we have emphasized the importance of

differentiation in doctor-patient relationships. The

next question is: Can developments in health care

informatics support relational responsibility in the

doctor-patient relationship? To answer this question

it is useful to distinguish between two forms of

health care informatics: consumer health informatics

(PHRs) and provider-oriented medical informatics

i

(EHRs) (Eysenbach, 2000).

Personal Health Records (PHRs) can be seen as a

form of consumer health informatics, because they

are designed to empower patients by giving patients

more access to health care information and in this

way bridging the knowledge gap between health

care professional (Eysenbach, 2000, Tang et al.,

2006). EHRs are manifold in appearance and

traditionally support the health care professional, or

its institution, to manage information about (not

from) patients.

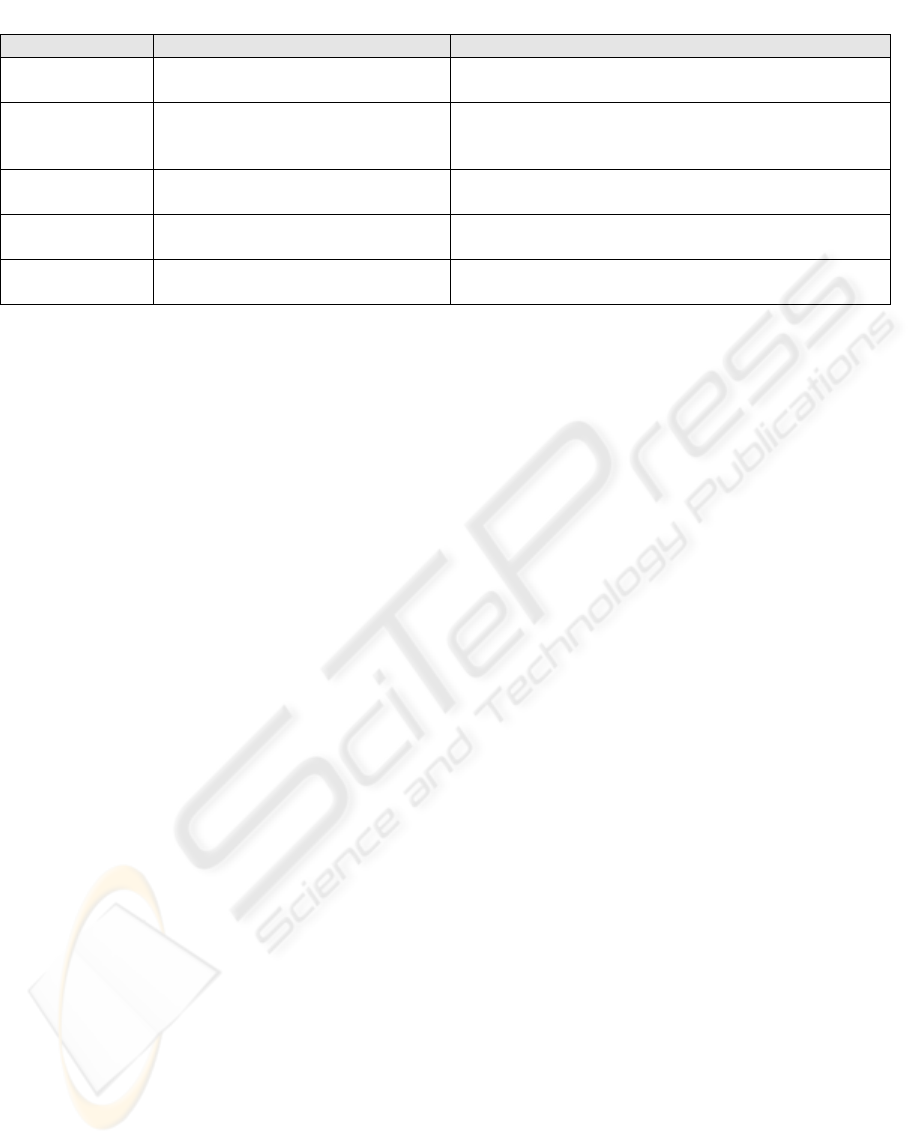

Table 1 shows the different development stages

of medical records

ii

. In more recent stages of

information technology the interoperability, i.e. the

degree in which it is possible to exchange

information, has increased significantly. This means

the fifth development stage, in which EHR and PHR

converge, has become technically possible. Due to

standardization and higher levels of interoperability,

both information written by the patient and

information written by the professional can be

exchanged

iii

. Such a convergence of EHR and PHR

would support relational responsibility because

patient and doctor can, depending on the particular

context of their communication, choose who adds

information to the health record, at what times this

information is read - and by whom.

Given this (theoretical) possibility of

convergence it is interesting to empirically study

whether countries are planning on realizing this

convergence and for what reasons. Do policy

makers acknowledge the need for differentiation in

doctor-patient relationships (relational

responsibility) and what is their perspective on

health informatics?

3 EMPIRICAL APPROACH

The empirical work concerns a qualitative,

explorative and comparative study, involving three

countries. For each country we studied:

- the institutional context: How is the EHR

implemented?

- EHR policy: What are the primary objectives of

the national EHR?

- functionalities of EHRs: What are the most im-

Table 1: development stages of EHRs and PHRs.

Stage Electronic Health records Personal health records

1. Computerizing Computerized records

Hand written notes; personal written annotations, personal

knowledge

2. Automating Automated systems

Manual entry into pc applications (word, excel, electronic

agenda). Stand-alone medical devices with computerized

records

3. Connecting

Digital organizational infrastructure

(e.g. hospital information systems)

Using medical devices and putting output of these devices

into journal / ehr-application

4. Networking Networked, distributed EHR

Automatic connections between devices and personal

EHR, synchronizing EHR with EPR by hand

5. Converging

Virtual, multidimensional records on

shared infrastructure

Automatic, multidirectional synchronization of PHR and

EHR

CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON INFORMATICS? - A Comparison of Three National Electronic Health Records

417

portant design features of the EHR and who can

use them (professionals and/or patients)?

- data: What data are exchanged through the EHR

and are these created by professionals and/or

patients?

The answers to these questions are based on the

study of policy and implementation documents.

4 EHR POLICY & DESIGN

4.1 Countries & Institutional Contexts

We have chosen to study the policy and design of

EHRs in Canada, Denmark and The Netherlands,

because these countries are actively working on a

national, generic EHR, and because they have a high

penetration of pc and Internet use. After all,

convergence is difficult if only a few people use

Internet. All three countries are in the top ten of the

United Nations E-government Readiness Index

(United Nations, 2008).

In Canada each province is creating its own

EHR, which in time should become interoperable.

Denmark and The Netherlands are working on one

nation-wide, generic EHR.

All three countries have founded and/or

appointed an implementation organization. In

Canada the federally funded organization ‘Health

Infoway’ is mandated to accelerate the development

and adoption of EHR’s (Canada Health Infoway,

2005). Infoway tries to create the basic infrastructure

that makes it possible to connect EHR systems and

in addition tries to distribute successful EHR

practices nationwide. In Denmark ‘Medcom’ is

responsible for the creation of an interoperable ICT-

network and communication standards (Medcom,

2007). In The Netherlands the Ministry of Health,

Welfare and Sport has appointed ‘NICTIZ’, the

national ICT institute for health care. NICTIZ has

developed a national ICT infrastructure for the

health care sector (NICTIZ, 2005).

4.2 EHR Policy: Primary Objectives

The table below gives on overview of the primary

objectives that follow from EHR policy documents

iv

.

Canadian policy makers directly link the EHR to

patient involvement, participation, education

(empowerment) and self-care, which are considered

important objectives. Danish government also makes

a direct link between patient access to EHRs and

their ability to actively participate in their healthcare

process. In The Netherlands the formal EHR

objectives are all oriented towards supporting

providers in the delivery of health care. However,

NICTIZ states in its brochure that it sees the EHR as

a way to increase patient’s autonomy, to take work

off health care professionals’ shoulders and to

increase the level of responsibility and involvement

(NICTIZ, 2005).

4.3 Functionalities of EHRs

Documentation (registration of health information)

and collection (retrieval of health information) are

the first functionalities that all three countries hope

to realize. In addition to this, Canada hopes that in

2015 other functionalities like order entry, public

visibility into wait times, Clinical Information

Systems and chronic disease management will be

available (Canada Health Infoway, 2005). Denmark

connects the EHR to various telemedicine projects in

Table 2: EHR policy: objectives of EHRS.

Canada Denmark The Netherlands

- Increasing quality of care

- Timely access to accurate information and

improved decision-making support

- Enhancing ongoing disease management

and longer-term care

- A higher level of patient involvement and

education

1

- Enabling patient self care/remote care

- Controlling system risks from pandemics or

other health issues

- More guideline-compliant treatment

- Manage wait times and improve patient

access

- Enhanced performance management of cost,

quality and access

(Canada Health Infoway, 2005)

- Enable the individual citizen to have safe

access to personal health-related

information

- Increased efficiency

- Quality assurance of health care

delivery, e.g. by fewer errors in

medication

- Improved quality of clinical decision-

making

- Shorter waiting times

- Supporting the citizens freedom of

choice

(Ministry of the Interior and Health, 2003)

- Continuity and quality of care

- Decrease in number of avoidable

medication errors

- Increasing safety of patients

- Increase in the efficiency of health

care

- More demand-driven health care, i.e.

preventing patients from

unnecessarily having to tell the same

story over and over again

(Ministry of Health, Welfare and

Sport, CIBG and NICTIZ, 2005 and

2008; Website of Ministry, 2008)

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

418

which the local nurse can perform certain activities

that in the past only specialists were allowed to

perform. In this way patients can be treated closer to

home.

In both Canada and The Netherlands health care

professionals first gain access to the EHR. The

Dutch NICTIZ is exploring the possibility of giving

patients access to their record through a patient

portal, but in the first year(s) patient access is only

possible by a paper print of the EHR (NICTIZ,

2005). The same applies to Canada: a patient portal

with self-help tools and basic EHR information

should be in place around 2015 (Canada Health

Infoway, 2005). In Denmark there is already a

patient portal in use, which is linked to the EHR

infrastructure. At “sundhed.dk” patients can find a

directory of names and addresses, make

appointments, get prescription renewals, contact

their GP through e-mail, compare prices, quality and

accessibility of care, by drugs online, receive

information about prevention and treatment, view

information on waiting lists, preventive medicine,

health laws and regulations and access their own

personal health data, i.e. their EHR (Ministry of

Interior and Health, 2003).

4.4 Data that are Exchanged

All data that are exchanged by the EHR

infrastructure in the three countries are created and

provided by the community of health care

professionals. Patients do not have the possibility to

add health related information to their EHR.

Within the basic Canadian infrastructure data

that will be exchanged are: a) client and provider

registries; b) Public Health Surveillance data (PHS);

c) drug data; d) laboratory data and e) Diagnostic

Imaging (DI).

For the most important data products in

Denmark, almost all paper forms have been replaced

by electronic forms. Hospital information and

treatment plans are now sent electronically to

municipal care centers (62%)

1

. GP’s receive

discharge letters (88%) and send prescriptions

(83%). Laboratories send lab results to GP’s and

hospitals (96%), after receiving lab requests (75%).

Reimbursement is almost entirely done

electronically (96%).

The first version of the Dutch EHR exchanges

medication data and a GP’s summary file that is to

be used by the local GP. Within a couple of years

NICTIZ also hopes to realize an emergency record, a

diabetes record and it hopes to integrate laboratory

data (NICTIZ, 2005).

5 CONCLUSIONS

In the first part of this paper we concluded that

differentiation in medical encounters is needed.

There are important ethical and practical reasons for

patient participation, but sometimes a more

traditional role division, in which patients have a

more passive role, can be preferable. Depending on

the relational context, patient and doctor need to

look for an optimal role division. Health informatics

can support such Relational Responsibility in

doctor-patient relationships, given that increasing

interoperability makes convergence of EHRs and

PHRs technically possible.

We empirically explored what norms and values

with respect to the role division between doctors and

patients are being stabilized in nation-wide EHRs –

both in policy and design. When we look at Canada,

Denmark and The Netherlands we can first conclude

that policy makers all to a greater or lesser extent

emphasize the importance of patient participation.

Canada has the most extensive vision on the EHR as

a means of empowering patients and promoting self-

care. When we look at the ways in which the EHRs

are implemented, we must conclude that we can only

find few traces of these visions on patient

participation in the current designs of EHRs.

Denmark and The Netherlands are ahead in realizing

an infrastructure for the national exchange of

medical information between professionals. In

Denmark the possibility of patient participation is

most developed through a patient portal that enables

patients to access information written by

professionals. However, in none of the countries

patients can add medical information that is written

by themselves to the record.

In none of the policy visions we find an explicit

recognition of the need to facilitate a differentiation

of role division in doctor-patient relationships. In

addition, the integration of EHR and PHR is in no

policy document, although Canada does plan on

creating self-help tools for patients and the

implementation organization in The Netherlands

values the idea of patients adding information to the

EHR.

In sum, for the upcoming years Electronic Health

Records will mainly support one traditional role

division: the one in which the health care

professional is in the lead and is the better-informed

party. Although the perspective on the doctor-patient

relationship seems to be changing towards more

patient participation, the current use of informatics

still seems to be provider-oriented.

Future research could explore how these policies

CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON INFORMATICS? - A Comparison of Three National Electronic Health Records

419

and designs of national EHRs work out in practice

and to what extent they restrict or support patient

participation.

REFERENCES

Bensing, J.M., Verhaak, P.F.M., Van Dulmen, A.M. and

Van den Brink-Muinen, A. (2004). Communication in

GP consultations. In: Van den Brink-Muinen, A., Van

Dulmen, A.M., Schellekens, F.G. and Bensing, J.M.

(eds.), Second national study into illnesses and

activities in the GP-practice, p. 14-35. Utrecht:

NIVEL.

Beun, J.G. (2003). Electronic Health Record: a way to

empower the patient. In: International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 69, p. 191-196.

Commission of the European Communities (2000). e-

Health - making healthcare better for European

citizens: An action plan for a European e-Health Area.

Brussels.

Canada Health Infoway (2005). Vision 2015: advancing

Canada’s next generation of health care.

Chia, R. (1996). The problem of reflexivity in or-

ganizational research. In: Organization, 3, 1, p.31-59.

EHTEL (2008). Sustainable Telemedicine: paradigms for

future-proof healtcare. Brussels: EHTEL.

Eysenbach, H. (2000). Consumer health informatics. In:

BMJ, 320, p.1713-16.

Hosking, D.M. (2007). Can constructionism be critical? In

J. Holstein & J. Gubrium (Eds.), Handbook of

Constructionist Research. New York: Guilford

Publications.

Jahng, K.H., Martin, L.R., Golin, C.E., DiMatteo. M.R.

(2005). Preferences for Medical Collaboration: Patient-

Physician Congruence and Its Associations with

Outcomes. In: Patient Education and Counseling, 57:

308-14.

McNamee, S., & Gergen, K.J. (Eds.). (1999). Relational

responsibility: resources for sustainable dialogue.

Thousands Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Medcom (2003). Medcom IV: status, plans and projects.

Copenhagen: Medcom.

Medcom (2007). On the threshold of a healthcare IT

system for a new era. Copenhagen: Medcom.

Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (2005). ICT in

healthcare: from Electronic Medical Record to

Electronic Patient Record.

Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, CBIG, NICTIZ

(2005). Implementation of Electronic Medical Record

and Observation Record GP’s.

Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (2008).

Implementation Electronic Health Record.

Ministry of the interior and health (2002). Health care in

Denmark. Copenhagen: Ministry of the interior and

health.

Ministry of the interior and health (2003). National IT

strategy for health, 2003-2007. Copenhagen: Ministry

of the interior and health.

NICTIZ (2005). Corporate brochure. Leidschendam:

NICTIZ.

Stilgoe, F. and Farook, F. (2008). The talking cure: why

conversation is the future of healthcare. London:

Demos.

Tang, P.C., Ash, J.S., Bates, D.W., Overhage, J.M. and

Sands, D.Z. (2006). Personal Health Records:

Definitions, Benefits, and Strategies for Overcoming

Barriers to Adoption. In: Jamai, 13, p. 121–126.

Todres, L., Galvin, K. and Dahlberg, K. (2007).

Lifeworld-led healthcare: revisiting a humanising

philosophy that integrates emerging trends. In:

Medicine, Healthcare and Philosophy, 10, pp. 53–63.

United Nations (2008). United Nations e-Government

survey 2008. New York: United Nations.

Van den Eerenbeemt, F. and Mulder, B. (2004). Samen

zorgen voor jezelf (Taking care of yourself together).

Den Haag: De Informatiewerkplaats.

i

The word ‘provider’ refers to the health care professional.

ii

The development of EHRs is patchy. Thinking in terms of

configurations can therefore be useful, in which certain

aspects of an EHR still belong to one of the former stages,

whereas certain other aspects are already congruent with later

stages.

iii

The choice for exchange and use of information depends on

contextual factors such as quality, privacy and relevance.

iv

In Canada and Denmark one integrated vision document with

both long-term and short-term objectives have been written.

In The Netherlands we had to study different information

sources to create an overview of objectives as formulated in

formal documents.

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

420