DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF AN AMBIENT INTELLIGENT

SYSTEM SUPPORTING DEPRESSION THERAPY

Fiemke Both, Mark Hoogendoorn, Michel Klein and Jan Treur

Department of Artificial Intelligence, Vrije Universiteit, De Boelelaan 1081a, 1081HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Keywords: Depression therapy, Mobile phone, Internet therapy, Activity scheduling.

Abstract: This paper addresses the design of an ambient intelligent system to support humans that follow “activity

scheduling” therapy to recover from a uni-polar depression. The system consists of a personalized website

and a mobile-phone based reporting a reminder system. To analyze the system, a previously developed

dynamic model is used to simulate a client. It is illustrated by interactive simulation that the system is more

effective than the plain internet-based therapy that is offered at the moment. In continuation of the work

described in this paper a clinical trial is planned in the first half of 2009.

1 INTRODUCTION

A clinical depression is one of the most prominent

disturbances in mood. It is a common psychiatric

disorder, affecting about 7–18% of the people at

least once in their lives. In the USA, the prevalence

is approximately 14 million adults per year.

Symptoms of a depression are a deep feeling of

sadness, and a noticeable loss of interest or pleasure

in favorite activities. There is not one specific cause

of a depression, most experts believe that both

biological and psychological factors play a role.

A variety of therapies is available to intervene

within a depression, such as cognitive therapy and

activity scheduling (Lewinsohn, Youngren and

Grosscop, 1979). The basis for activity scheduling is

that a depression can be treated by increasing the

positive reinforcement through increasing the

quantity and quality of activities. Recently, it is

shown that activity scheduling interventions offered

via the Internet are very effective (Spek et al, 2007).

The problem with such Internet inventions is

however that the patient is not continuously

supported in the therapy. Having this more

continuous support might lead to a more effective

intervention. Therefore, this paper aims at given the

patient support via the mobile phone. The advantage

of using a mobile phone is that patients typically

carry this device around with them most of the time.

The support model is specified in a formal fashion to

allow for logical simulation. In order to evaluate the

effectiveness of the continuous support, a

computational model (cf. Both, Hoogendoorn, Klein

& Treur, 2008) of mood and depression is used to

investigate the influence of the support upon these

factors.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2,

first summarizes the dynamic model for depression

adopted from (Both et.al., 2008). Section 3 briefly

describes the idea of activity scheduling. In the next

section, the ambient intelligent system model to

support activity scheduling is described. In Section

5, a simulation of two different scenarios based on

the dynamic client model is explained. This shows

that, according to the models, the system is more

effective than plain internet-based support. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and describes the

clinical trial that to evaluate the system in practice

that is planned for the second half of 2008.

2 DYNAMIC MODEL OF

DEPRESSION

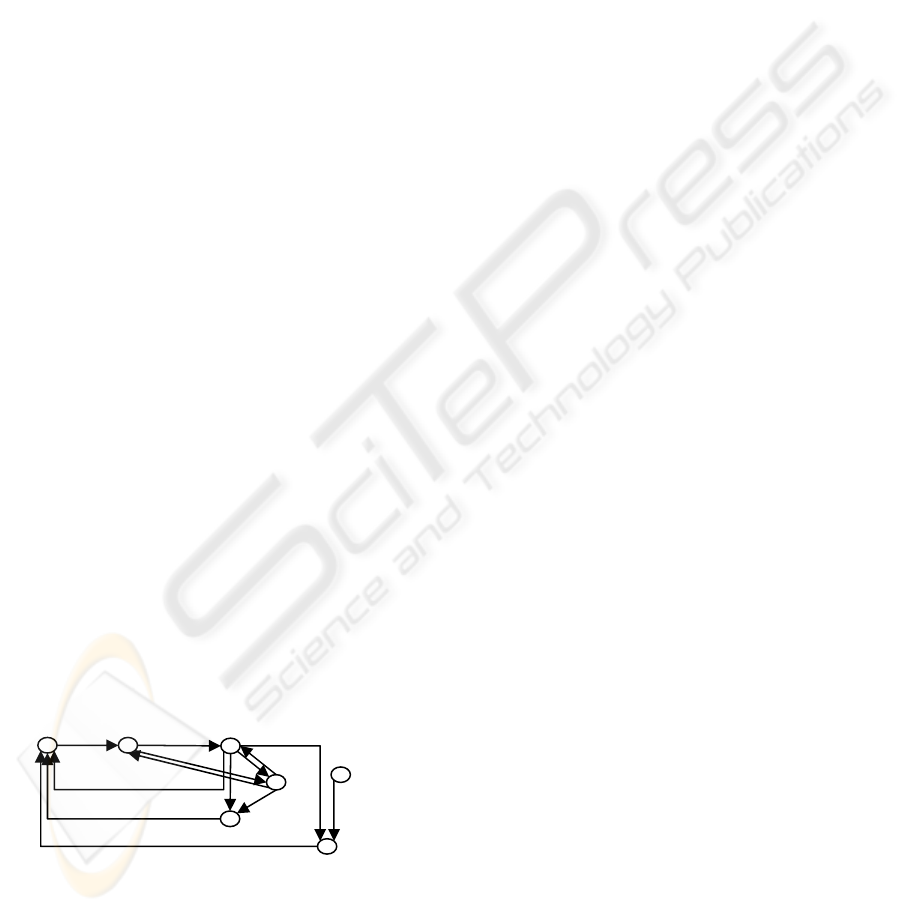

Figure 1 gives a conceptual overview of the model

developed in (Both et.al., 2008), which is based on

the major theories about a uni-polar depression. In

the model, it is assumed that every situation has an

emotional value, which represents the extent to

which a situation is experienced as something

positive.

The objective emotional value of situation

(OEVS) represents how an average person would

perceive the situation. A situation can be an event or

series of events one has no control over, or that are

chosen or influenced by the person. The subjective

emotional value of situation (SEVS) can differ from

142

Both F., Hoogendoorn M., Klein M. and Treur J. (2009).

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF AN AMBIENT INTELLIGENT SYSTEM SUPPORTING DEPRESSION THERAPY.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 142-148

DOI: 10.5220/0001432501420148

Copyright

c

SciTePress

OEVS when the thoughts of the person are more

positive or more negative than average. Negative

thoughts will cause the SEVS to be lower than

OEVS, which is often the case with a depression.

How one perceives the situation (SEVS) influences

the mood one is in and the thoughts one has. When

the person is in a positive situation, mood level and

thoughts will increase. For example, attending a

birthday party, which is usually a positive

experience, causes a better mood and more positive

thoughts. In contrast, an argument with a close

friend has a low emotional value and causes a bad

mood and negative thoughts. By changing or

choosing a situation, one can influence their own

mood level (e.g. choosing to go to the birthday party

when one feels down increases the mood level). The

complex notion of mood is represented by the

simplified concept mood level, ranging from low

corresponding to a bad mood to high corresponding

to a good mood. The mood level influences and is

influenced by thoughts. Positive thinking has a

positive effect on the mood and vice versa. The

mood level someone strives for, whether conscious

or unconscious, is represented by prospected mood

level. This notion is split into a long term prospected

mood level, an evolutionary drive to be in a good

mood, and a short term prospected mood level,

representing a temporary prospect when mood level

is far from the prospected mood level. The node

sensitivity represents the ability to change or choose

situations in order to bring mood level closer to

prospected mood level. A high sensitivity means that

someone’s behavior is very much affected by

thoughts and mood, while a low sensitivity means

that someone is very unresponsive. The level of

sensitivity itself is influenced by mood level and

thoughts. A low mood level and negative thoughts

can decrease the sensitivity and a high mood level

and positive thoughts can increase the sensitivity.

Mood level, prospected mood level and sensitivity

together influence OEVS by choosing or changing a

situation.

Figure 1: Model of mood dynamics.

The new value of a node is determined by

preceding nodes and the previous value of that node.

Decay factors determine how fast the previous value

of the node decays. For the entire model there are

two decay factors: diatheses for downward

regulation and coping for upward regulation. The

term diatheses represents the vulnerability one has

for developing a depression. The term coping

represents the skills one has to deal with negative

moods and situations. A person with very low

diatheses will probably never get a depression,

because mood, thoughts and sensitivity will go down

very slowly with a negative event. That person is

therefore always capable of choosing situations that

have a positive influence on his/her mood level and

emotions. High diatheses and low coping skills will

cause a person to get a depression very easily when

a negative event occurs, because mood, thoughts and

sensitivity will decrease fast. It will be very difficult

to climb out of a depression: the upward regulation

of mood, thoughts and sensitivity will go very slow.

3 ACTIVITY SCHEDULING

Activity scheduling (AS, also called behavioral

activation) is an intervention for clinical depression

based on a theory by Lewinsohn, Youngren &

Grosscop (1979) who say that a low rate of behavior

(often caused by inadequate social skills) is the

essence of a depression and the cause of all other

symptoms. Part of his theory is the hypothesis that

there is a causal relationship between lack of

positive reinforcement from the environment and the

depression. A depression can be treated by

increasing the positive reinforcement through

increasing the quantity and quality of (social)

activities. Many studies have shown that this type of

intervention works just as well as or even better than

other popular treatments, such as cognitive

(behavior) therapy (CT or CBT) and antidepressant

medication (Dimidjian et al, 2006; Jacobson et al,

1996; Iqbal & Bassett, 2008). Recently, it is shown

that interventions offered via the internet are very

effective (Christensen et al, 2004; Proudfoot, 2004,

Andersson et al, 2005, Spek et al, 2007).

There are two stages in AS: the first stage is

observing that pleasant activities and a good mood

come together by writing down all pleasant activities

and mood level. Usually, the more pleasant activities

have been performed, the better the mood has been.

The second stage is changing the activity schedule

so that the patient participates in more pleasant

activities with the goal of increasing the mood level.

By doing more pleasant activities in stage 2, the

mood increases on a short term, and by learning that

pleasant activities influence mood level positively,

patients are more capable of dealing with future

situations. In our model of mood and depression,

these effects can be seen as a positive influence on

sensitivity

mood level

subj. emotional value

of situation

thoughts

obj. emotional value

of situation

LT prospected

mood level

ST prospected

mood level

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF AN AMBIENT INTELLIGENT SYSTEM SUPPORTING DEPRESSION THERAPY

143

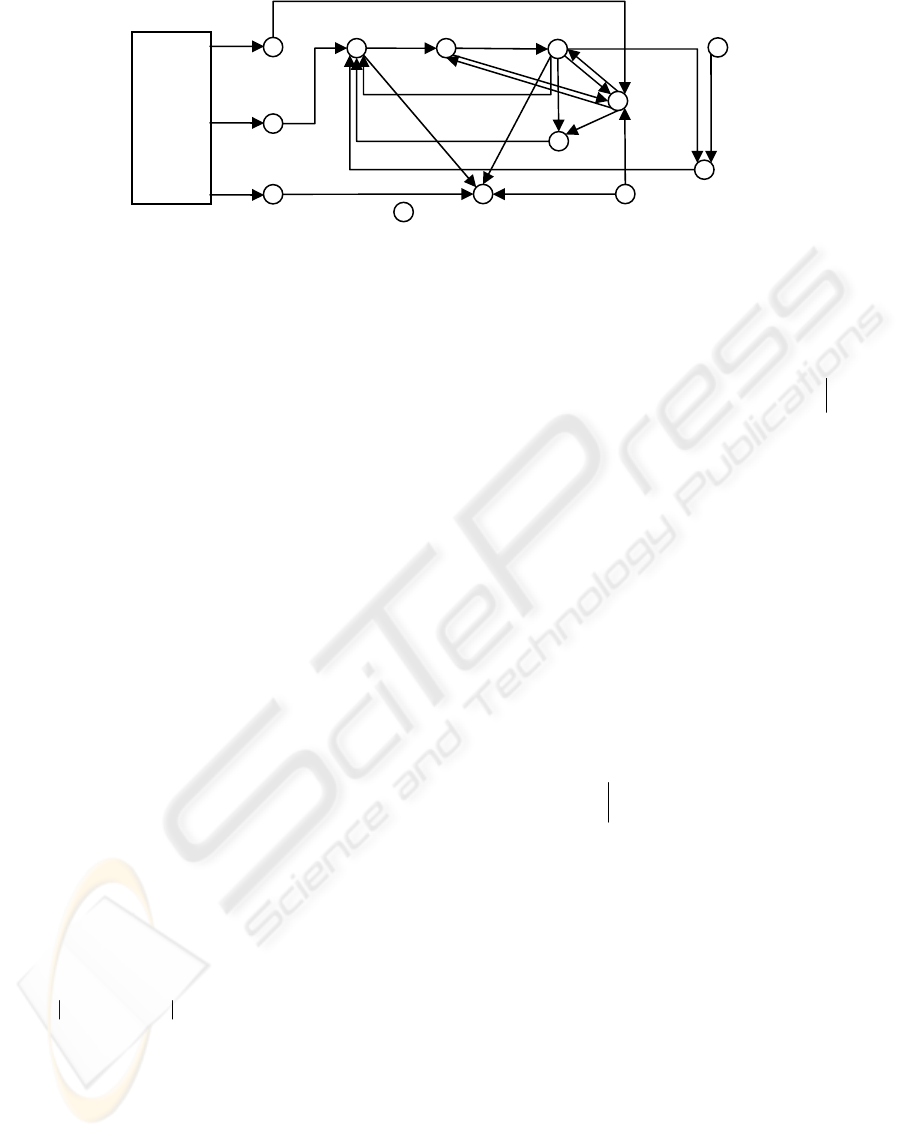

Figure 2: Effect of activity scheduling therapy in the depression model.

OEVS (increasing the number of positive activities),

thoughts and coping (learning that pleasant activities

lead to a better mood on short term and long term).

By first showing the patient that positive situations

increase mood level, negative thoughts about self,

others and world will decrease. This will result in a

higher sensitivity: the patient is more capable of

choosing a situation that increases the mood level.

When the patient is more able to choose positive

situations both by an increased sensitivity and by

stimulation from the AS intervention, the patient

will perceive the situation better and the mood level

will go up.

There may also be an initial positive influence on

the short-term prospected mood level when a person

with depression seeks counseling. This may explain

the placebo effect of antidepressant medication and

the ‘fact’ that people on a waiting list improve.

The influence of the activity scheduling occurs

on three places within the model. First of all, the

planning of activities can be used to determine the

new OEVS. Secondly, the fact that the patient is

undergoing the activity therapy will influence the

thoughts in a positive way (intervention). Finally,

activity scheduling makes the patient aware of the

relationship between OEVS and the mood level

resulting in better coping skills (reflection). Below,

in Figure 2, the graphical representation is shown.

The sensitivity for therapy influences the impact of

AS on thoughts and coping.

In the model coping is calculated as follows.

The idea behind the formula is that the patient is

learning the relationship between mood and the

OEVS. This means that the patient will learn faster

in case the two are closer. Furthermore, the more

sensitive the patient is for therapy, the faster this

learning process will go. For the calculation of

thoughts the following formula is used, which takes

the positive influence of the therapy into account:

In case the condition holds, the former is true,

otherwise the latter. The formula specifies that in

case the activity scheduling therapy is undergone

(i.e.

intervention(t) = 1) the thoughts are positively

influenced by multiplying the difference between

“optimal” thoughts (i.e. 1) and actual thoughts (i.e.

the current thoughts plus the difference caused by

the other states) with the sensitivity for the therapy.

The emotional value of a situation is determined

by the current and prospected mood levels, the

sensitivity for choosing optimal situations and the

activities done according to the AS therapy. When a

pleasant activity is done, the formula for OEVS is as

follows.

where w1 is the influence of the ability to choose a

good situation, and w2 is the influence of the

activities planned following the AS therapy.

4 DESIGN OF THE AMBIENT

ASSISTIVE SYSTEM

The activity scheduling therapy is provided in

different ways, for example with support of a

therapist (Lewinsohn et al, 1986), via self-help

books (also called bibliotherapy, e.g. Clarke 1990)

and as internet-based course.

4.1 Overall System Design

The system presented in this paper functions as a

activity

scheduling

intervention

sensitivit

y

mood level

subj. emotional

value of situation

thoughts

obj. emotional

value of situation

LT prospected

mood level

ST prospected

mood level

co

p

in

g

sensitivity

for therapy

vulnerabilit

y

reflection

activities

mood_prosp_lt)t(mood

))t(oevs(

)t(oevs

)t(activitiesw)t)t(ysensitivit)t(oevs(w)tt(oevs

mood

mood

mood

mood

mood

⋅−=

<

>=

⋅−

⋅

=

⋅+Δ⋅⋅−⋅=Δ+

βδ

δ

δ

δ

δ

ϕ

ϕ

0

0

1

21

t))t(coping())t(mood)t(oevs(

)t(therapy_for_ysensitivit)t(reflection()t(coping

)tt(coping

Δ⋅−⋅−−

⋅⋅+

=Δ+

11

)(__)(int

)()(

)(

)(

)))(()((1())(()(

)))(()((1())(()(

)(

__

ttherapyforysensitivitterventionI

wtmoodwtsevs

tth

tth

tItthdiathesestthtthdiathesestth

tItthcopingtthtthcopingtth

ttthoughts

thoughtsmoodthoughtssevs

⋅=

⋅+⋅=

<

>=

Δ⋅⋅−⋅+−+−⋅+

Δ⋅⋅−⋅+−+−⋅+

=Δ+

φ

φ

φ

φφ

φφ

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

144

combination of an internet-based course and the use

of smartphones: a patient plans his course via the

internet, where a server maintains personal data of

the patient and keeps track of his progress and

status; based on this status, the patient receives

personalized support via a smartphone.

Figure 3: Combined smartphone and internet support.

The basic ingredients of the internet course are

keeping a regular diary of activities and the

perceived mood, and planning and performing

pleasant activities, possibly supported by small

rewards. The assistive system helps with both tasks.

At the start of the course, the patient first has to

define his personal ordering of pleasant activities

and a list of rewards (such as “buying my favorite

magazine). For the first task of the course (keeping

the diary), the patient has to register every day the

number of pleasant activities he has undertaken and

a grade for his perceived mood. In the internet-only

version of the course, he has to do this every day

behind a computer. With the assistive system, he

will be able to report this via a simple interface on a

smartphone. For this, the phone shows the pre-

defined list of pleasant activities and allows the user

to check the activities that he has undertaken or add

a new pleasant activity. In addition, the user is asked

to rate his own mood on a scale from 1 to 10. All

provided information is then stored in the personal

profile at the web server. Because of the mobility of

the phone, the user can choose to report his activities

and mood on a more frequent basis than the per day

basis in the internet-only version, e.g. per morning,

afternoon and evening. As a consequence, the

system will result in a more fine-grained registration

of the mood, and therefore probably help people to

recognize the relation between pleasant activities

and mood earlier.

In the second phase of the course, the patient has

to plan activities. This is normally done via the

website. In this phase, the system can support by

sending reminders to the phone before the planned

start of an activity. It is up to the user to define for

which type of activity reminders are desired. For

example, activities that require a long preparation do

not benefit from short-term reminders. The

reminders could stimulate people to better keep to

their planning and thus doing more pleasant

activities. After a planned activity, the system will

ask the user whether he indeed undertook the

activity, how pleasant it was, and how he feels. The

system will give immediate positive feedback if the

mood is higher than before, e.g. ‘good to see that

you feel better now after playing tennis than you felt

this morning’. This again helps the patient to see the

relation between activities and mood. In addition,

the system will suggest to effectuate some of the

rewards if some progress has been made (e.g. a

number of pleasant activities have been performed).

After a few days of doing activities, the system

can analyze the activities and mood levels and give

personalized advice about how to proceed. For

example: ‘activity x was not as pleasant as you

thought, maybe you shouldn’t schedule it for next

week’, or ‘you have done many expensive activities,

is that why your mood is not improving?’.

The internet is the main interface that is used for

the longer term feedback. Via his personal website,

the user can consult tables and graphs that show the

relation between the number of activities undertaken

and the reported mood. Also, the long term

development of the mood level can be shown. The

user can also request this information via the

smartphone.

4.2 System Rules

Phase 1

1. if pre-set time interval has passed, prompt user

via smartphone to check the activities that have

been performed

∀I, I2:integer

frequency_set_for_first_stage(I) ∧

current_time(I2) ∧ (I2 mod I = 0) →

output(check_activities_please)

2. if pre-set time interval has passed, prompt user

via smartphone to report mood level

∀I, I2:integer

frequency_set_for_first_stage(I) ∧

current_time(I2) ∧ (I2 mod I = 0) →

output(score_mood_level_please)

Phase 2

3. if it is less than X minutes before a planned

activity and the type of activity is set to receive a

reminder, send a reminder to the smartphone

∀I, I2:integer, A:ACTIVITY

activity_scheduled_begin_time(A, I) ∧

reminder_active(A) ∧ current_time(I2) ∧

I2 = I – X →

output(do_not_forget_to_perform_activity, A)

4. if X minutes have been passed after a planned

activity, ask the user whether the activity has

been performed

∀I, I2:integer, A:ACTIVITY

activity_scheduled_end_time(A, I) ∧

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF AN AMBIENT INTELLIGENT SYSTEM SUPPORTING DEPRESSION THERAPY

145

current_time(I2) ∧ I2 = I + X →

output(did_you_perform_actitvity, A)

5. if the activity has been performed, prompt the

user to rate the pleasantness of the activity and

his mood

∀A:ACTIVITY

input(performed_activty, A, yes) →

output(score_mood_level_please)

6. if the reported mood level is higher than the

previously reported mood level, and the activity

was pleasant, give positive feedback message

∀I, I2:integer

input(mood_level, I) ∧ previous_input(mood_level, I2) ∧

I > I2 ∧ I > BOUNDRY_POSITIVE_MOOD

→ output(well_done_progress_can_be_seen)

7. if the first pleasant activity during the course has

been performed, suggest a reward from the

predefined list via the smartphone

∀I, I2:integer, A, A2:ACTIVITY, R:REWARD

input(performedactivity, A, yes) ∧

previous_input(performed_activity, A2, no) ∧

suitable_reward(A, R)

→ output(well_done_reward_yourself, R)

4.3 Example System Simulation

The intervention as described in the previous section

has been implemented in a simulation environment,

i.e. LEADSTO (Bosse et al,, 2007). Using this

environment, we mimicked the functioning of the

cell phone system in different scenarios. The results

of using the cell phone system in the first stage of

the activity scheduling therapy are shown in Figure

4. In the figure, the x-axis represents time (in hours)

whereas the y-axis indicates the atoms that occur

over time. In the figure a dark box indicates that the

atom is true at a particular time point, whereas a

grey box indicates it is false. It can be seen that a

frequency is initially set by the patient to receive

messages every five hours:

input(frequency_of_first_stage, 5)

As a result, the patient receives two messages asking

him to check the activities and the mood level:

output(score_mood_level_please)

output(check_activities_please)

Thereafter the patient responds with the answer that

the mood level is 2, and one activity which has been

performed, namely walking in the park:

input(mood_level, 2)

input(performed_activity, walk_in_the_park, yes)

Of course, the process continues every five hours,

but these have been left out for the sake of clarity.

The output of the support system for the second

run is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the

patient inputs the schedule for the day, including a

period of running from 15:00 till 16:00, going out

for dinner between 19:00 and 20:00 and going to a

birthday of a friend between 23:00 and 24:00:

input (activity_scheduled_begin_time (go_running, 15))

input (activity_scheduled_end_time(go_running, 16))

input (activity_scheduled_begin_time

(go_out_for_dinner,19))

input(activity_scheduled_end_time(go_out_for_dinner,20))

input (activity_scheduled_begin_time

(go_to_friends_birthday, 23))

input (activity_scheduled_end_time

(go_to_friends_birthday, 24))

Furthermore, reminders are set active for all

activities except for the running activity. After the

running activity schedule indicates the activity has

ended, the cell phone system asks the patient

whether the activity has been performed:

output(did_you_perform_activity, go_running)

The patient answers that this activity has not been

performed. Just before the going out for dinner

activity has been scheduled the cell phone sends a

warning, since warnings are enabled for this activity:

output(do_no_forget_to_perform_activity,

go_out_for_dinner)

After the activity is finished the cell phone asks

whether the activity has been performed, which is

indeed the case in the trace. As a result, the cell

phone sends an encouraging message (since

previously a scheduled activity was not performed):

output(well_done_reward_yourself_with,

buy_nice_present_for_yourself)

Moreover, a question is posed what the mood level

of the patient is, which is in this case ranked as 5:

input(mood_level, 5)

For the final activity scheduled for the day, a

reminder is sent again. After the activity has been

scheduled, a question is posed by the cell phone

again whether the activity has been performed. This

is indeed the case, resulting in the used scoring the

mood level which is now a 7. Since the mood has

increased compared to the previous mood level, the

cell phone sends a message:

output(well_done_progress_can_be_seen)

input(frequency_of _first_stage, 5)

output(check_activities_please)

output(score_mood_level_please)

input(mood_level, 2)

input(performed_activity, walk_in_the_park, yes)

time

0 0.5 1 1.5 2

Figure 4: Results using the cell phone system in phase one.

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

146

input(activity_scheduled_begin_time(go_running, 15))

input(activity_scheduled_end_time(go_running, 16))

input(activity_scheduled_begin_time(go_out_for_dinner, 19))

input(activity_scheduled_end_time(go_out_for_dinner, 20))

input(activity_scheduled_begin_time(go_to_friends_birthday, 23))

input(activity_scheduled_end_time(go_to_friends_birthday, 24))

input(reminder_active(go_out_for_dinner))

input(reminder_active(go_to_friends_birthday))

suitable_reward(go_out_for_dinner, buy_nice_present_for_yourself)

reminder_active(go_out_for_dinner)

reminder_active(go_to_friends_birthday)

output(did_you_perform_activity, go_running)

input(performed_activity, go_running, no)

output(do_not_forget_to_perform_activity, go_out_for_dinner)

output(did_you_perform_activity, go_out_for_dinner)

input(performed_activity, go_out_for_dinner, yes)

output(well_done_reward_yourself_with, buy_nice_present_for_yourself)

output(score_mood_level_please)

input(mood_level, 5)

output(do_not_forget_to_perform_activity, go_to_friends_birthday)

output(did_you_perform_activity, go_to_friends_birthday)

input(performed_activity, go_to_friends_birthday, yes)

input(mood_level, 7)

output(well_done_progress_can_be_seen)

time

0 5 10 15 20 25 3

0

Figure 5: Results using the cell phone system in phase 2.

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 260

tim e

value

oevs

sevs

mood

thoughts

Figure 6: Unhealthy person, 1 negative event, no therapy.

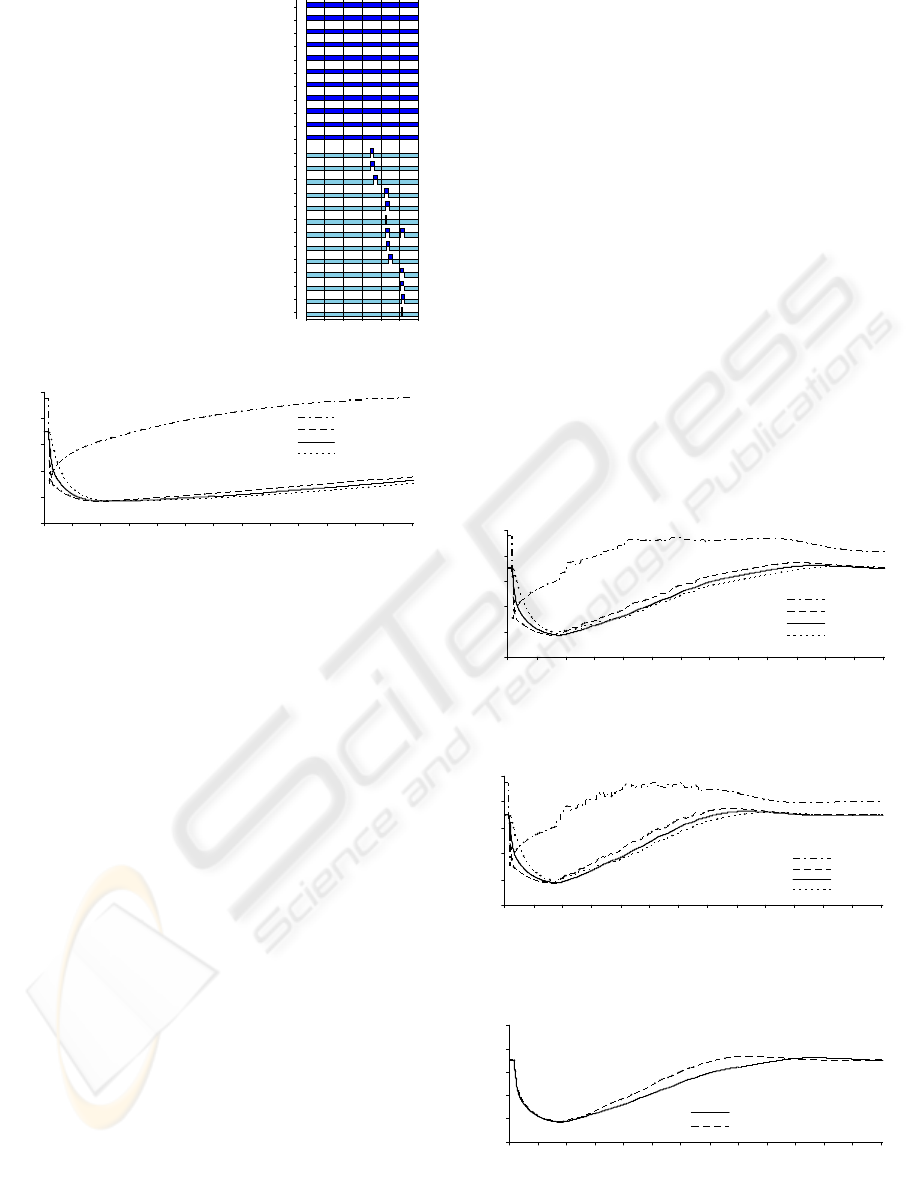

5 SIMULATION-BASED

ANALYSIS OF THE SYSTEM

To analyze the system, a number of system

simulations have been performed in interaction with

a simulated client. In this interactive simulation

processes, the simulation for the system is based on

the model description in Section 4, the simulation of

the client is based on the mood dynamics model

described in Section 3. A selection of the results is

shown in Figures 6 to 9. These results show how the

supporting system has a substantial impact on the

course of the depression.

All figures show the simulated mood level

(continuous line) of a patient that has relative high

vulnerability and low coping skills. In addition, the

average objective emotional value of all events

(oevs) is shown, the perceived emotional value of

the situation (sevs), and the simulated thoughts level.

At time point 3 an event with a negative

emotional value occurs. As can be seen in all

figures, this event causes a depression in the patient:

the mood-level decreases. In Figure 6, which

represents a patient that does not receive therapy,

one can see that the average objective emotional

values of the situations increases, but that this is not

directly followed by the mood-level of the patient.

Figure 7 represents a patient (with otherwise the

same conditions as in the patient represented by

Figure 6) who receives web-based activity

scheduling therapy. The figure clearly shows that the

therapy helps to recover from the depression. The

capricious line for the objective emotional value is

caused by the pleasant activities that are undertaken

by the patient, stimulated by the therapy. In addition,

although not directly visible in the graph, the

interventions in the therapy have a positive effect on

the thoughts, and the reflection about the relation

between activities and the perceived emotional value

of the situation causes an increase in of the coping

skills.

Finally, Figure 8 shows a representation of the

same patient that follows the same therapy, but now

supported by the ambient assistive system. The

difference with the previous scenario is that the

system, following the rules described in Section 4,

helps the patient to keep to his own schedule (thus

increasing the number of pleasant activities) and is

giving positive feedback (thus further increasing the

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 26

0

tim e

value

oevs

sevs

moo d

thoughts

Figure 7: Unhealthy person, 1 negative event, web-based

activity scheduling therapy.

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 26

0

time

value

oevs

sevs

moo d

thoughts

Figure 8: Unhealthy person, 1 negative event, web-based

activity scheduling therapy with smartphone.

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 260

time

value

mood AS therapy

mood AS therapy smartphone

Figure 9: Comparison of mood level between activity

scheduling with and without smartphone.

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF AN AMBIENT INTELLIGENT SYSTEM SUPPORTING DEPRESSION THERAPY

147

reflection and consequently the coping skills).

Figure 9 depicts the mood-level of both types of

therapy in one diagram. The additional effect of the

supportive system is that the patient recovers more

quickly from the depression, and that his coping

skills at the end of the simulation are higher.

6 DISCUSSION

In this paper the design of an ambient intelligent

system to support people that receive activity

scheduling therapy is introduced. The system adds

personalized support for patients by analyzing their

behavior and giving them reminders, advices and

feedback during the therapy. Although the system

acts according to static rules, the rules are triggered

by actions (or the lack of actions) of patients, and as

such it provides personalized actions. The main rules

of the system are described and formalized in a

simulation environment, thus allowing for

automated simulation of the system.

Secondly, based on an earlier model of the

dynamics of mood and depression, an extension is

presented that explains the effect of (activity

scheduling) intervention. This extended model is

used to simulate a patient that receives therapy.

Together with the simulation of the system, it is

shown that the ambient assistive system indeed helps

a patient to recover more quickly from a depression,

by improving his adherence to the therapy and

increasing the level of feedback. Of course, these

conclusions are dependant on the assumptions that

underlie the model; however, as have been shown in

earlier work (Both et.al., 2008), the assumptions are

in line with the major psychological literature about

depression (therapy). Therefore, it seems reasonable

to use the model to evaluate the added value of a

specific type of support.

In the first half of 2009, a clinical trial is planned

in which this system will be tested in practice. This

requires a more detailed development of the

interface used in the smartphone to allow for simple

reporting of the mood level and performed activities.

In the future, we will work on a new version of the

system that uses the model of depression and

therapy described in this paper to reason about the

state of the patient. Using this, it would be possible

to give even more personalized advices, based on the

predicted effect of the behavior of a patient. This

would require a more thorough validation of the

model for mood and depression, as the actions of the

system will then depend on its correctness. In the

current version, there are no ethical deliberations, as

all proposed actions towards patients are already

validated and tested as part of the existing therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank prof. dr. Pim Cuijpers for his

contribution to the development of this intervention.

REFERENCES

Andersson, G., J. Bergstrom, F. Hollandare, P. Carlbring,

V. Kaldo & L. Ekselius (2005). Internet-based self-

help for depression: randomised controlled trial.

British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 456-461.

Bosse, T., Jonker, C.M., Meij, L. van der, and Treur, J.

(2007). A Language and Environment for Analysis of

Dynamics by Simulation. International Journal of AI

Tools, vol. 16, 2007, pp. 435-464.

Both, F., Hoogendoorn, M., Klein, M.A., and Treur, J.,

Formalizing Dynamics of Mood and Depression

(2008). In: Ghallab, M. (ed.), Proceedings of the 18th

European Conference on Artificial Intelligence,

ECAI'08. IOS Press 2008, pp. 266-270

Christensen, Helen.;Griffiths, Kathleen M.; Jorm, Anthony

F. Delivering interventions for depression by using the

internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004 Jan

31;328(7434):265.

Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H. (1990). Instructor’s

Manual for the Adolescent Coping with Depression

Course. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press.

Dimidjian, S. et al., Randomized trial of behavioral

activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant

medication in the acute treatment of adults with major

depression, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74 (2006), pp.

658–670.

Iqbal, S., M. Bassett (2008) Evaluation of perceived

usefulness of activity scheduling in an inpatient

depression group. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental

Health Nursing 15 (5) , 393–398.

Jacobson, N.S., Dobson, K.S., Truax, P.A., Addis, M.E.,

Koerner, K., Gollan, J.K., Gortner, E., & Prince, S.E.

(1996). A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral

treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 62, 295-304.

Lewinsohn, P.M., Youngren, M.A., & Grosscup, S.J.

(1979). Reinforcement and depression. In R. A. Dupue

(Ed.), The psychobiology of depressive disorders:

Implications for the effects of stress (pp. 291-316).

New York: Academic Press.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Munoz, R.F., Youngren, M.A., et al

(1986) Control Your Depression. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Moore, R., Lopes, J., 1999. Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. INSTICC Press.

Proudfoot, J. (2004). Computer-based treatment for

anxiety and depression: is it feasible? Is it effective?

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Rev 28, 353-363.

Spek, V.R.M., Nyklicek, I., Smits, N., Cuijpers, P., Riper,

H., Keyzer, J.J., & Pop, V.J.M. (2007). Internet-based

cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold

depression in people over 50 years old: A randomized

controlled clinical trial. Psychological Medicine,

37(12), 1797-1806.

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

148