COMPARISON OF ANALYTIC APPROACHES FOR

DETERMINING VARIABLES

A Case Study in Predicting the Likelihood of Sepsis

Femida Gwadry-Sridhar, Benoit Lewden, Selam Mequanint

Lawson Health Research Institute, I-THINK Research Lab, London, ON, Canada

Michael Bauer

Department of Computer Science, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

Keywords: Sepsis, Decision support, Decision trees.

Abstract: Sepsis is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity and is often associated with increased hospital

resource utilization, prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stay. The economic burden associated

with sepsis is severe. With advances in medicine, there are now aggressive goal oriented treatments that can

be used to help these patients. If we were able to predict which patients may be at risk for sepsis we could

start treatment early and potentially reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity. Analytic methods currently

used in clinical research to determine the risk of a patient developing sepsis may be further enhanced by

using multi-modal analytic methods that together could be used to provide greater precision. Researchers

commonly use univariate and multivariate regressions to develop predictive models. We hypothesized that

such models could be enhanced by using multi-modal analytic methods that together could be used to

provide greater precision. In this paper, we analyze data about patients with and without sepsis using a

decision tree approach. A comparison with a regression approach shows strong similarity among variables

identified, though not an exact match. We compare the variables identified by the different approaches and

draw conclusions about the respective predictive capabilities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is defined as infection plus systematic

manifestations of infection (Dellinger et al., 2008).

Severe sepsis is considered present when sepsis co-

exists with sepsis-induced organ dysfunction or

tissue hypo-perfusion (Dellinger et al., 2008). Sepsis

can result in mortality and morbidity, especially

when associated with shock and/or organ

dysfunction (Angus et al., 2001). Sepsis can be

associated with increased hospital resource

utilization, prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) and

hospital stay, decreased long-term health related

quality of life and an economic burden estimated at

US $17 billion each year in the United States alone

(Brun-Buisson et al., 1995; Salvo et al, 1995; Pittet

et al., 1995; Angus et al., 2001). In Canada, there are

limited data on the burden of severe sepsis; however,

costs in Quebec may be as high as $73M per year

(Letarte, Longo, Pelletier, Nabonne & Fisher, 2002),

which contribute to estimates of total Canadian cost

of approximately $325 M per year.

Patients with severe sepsis generally receive their

care in the ICU. A multicentre study of sepsis in

teaching hospitals found that severe sepsis or septic

shock is present or develops in 15% of ICU patients

(Alberti et al., 2002). However, diagnosing sepsis is

difficult because there is no “typical” presentation

despite published definitions for sepsis (American

College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care

Medicine Consensus Conference 1992; Levy et al.,

2003).

In the Canadian Sepsis Treatment And Response

(STAR) registry (mix of teaching and community

hospitals across Canada), the total rate for severe

sepsis was 19.0%. Of these, 63% occurred after

hospitalization.

With advances in medicine there are now

aggressive goal oriented treatments that can be used

90

Gwadry-Sridhar F., Lewden B., Mequanint S. and Bauer M. (2009).

COMPARISON OF ANALYTIC APPROACHES FOR DETERMINING VARIABLES - A Case Study in Predicting the Likelihood of Sepsis .

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 90-96

DOI: 10.5220/0001554100900096

Copyright

c

SciTePress

to help these patients (Rivers et al., 2001; Minneci,

Deans, Banks, Eichacker, & Natanson, 2004;

Bernard et al., 2001). If researchers were able to

predict which patients may be at risk for sepsis we

could start treatment early and potentially reduce the

risk of mortality and morbidity. Therefore, methods

that can be developed to help with the early

diagnosis of patients who either present with sepsis

or develop sepsis in hospital are needed.

A variety of analysis techniques can be used to

identify relationships among a set of measured

variables or quantities. We hypothesized that

analytic methods currently used in clinical research

to determine the risk of a patient developing sepsis

may be further enhanced by using multi-modal

analytic methods that together could be used to

provide greater precision. Researchers commonly

use univariate and multivariate regressions to gather

information about variables that are associated with

the dependent variable, which in this case is whether

the patient contracted sepsis or not. However,

sometimes these models are constrained as we either

use univariate analysis to guide our decision on

which variable to include or rely on the literature to

guide the variable selection. Earlier work had looked

at the use of regression techniques to develop a

linear predictive model or mortality and length of

stay, but not sepsis (Martin et al., 2008).

In this paper, we consider the use of decision tree

analysis and cluster analysis. Decision trees are

interesting since they provide a prescriptive

approach for arriving at a decision with an

associated probability. In contrast, cluster analysis

takes a holistic approach to partition the data into

similar but disjointed sets. We were interested in

using these approaches to identify the key variables

or variable sets that can be used to predict the

likelihood of sepsis or not having sepsis in patients.

2 DATA IN STUDY

We obtained data that was collected from 12

Canadian intensive care units that were

geographically distributed and included a mix of

medical and surgical patients (Martin et al., 2008).

Data were collected on all patients admitted to the

ICU who had an ICU stay greater than 24 hours or

who had severe sepsis at the time of ICU admission.

Patients who were not anticipated to obtain to

receive active treatment were excluded.

Hospitals collected a minimum data set on all

eligible patients admitted to the ICU. This included

demographic information and data about their

admission, source of admission, diagnosis, illness

severity, outcome and length of ICU and hospital

stay. Illness severity scores were calculated using

data obtained during the first 24 hours in the ICU

(Knaus, Draper, Wagner, & Zimmerman, 1985;

Knaus et al., 1991). All patients were subsequently

assessed on a daily basis for the presence of

infection and severe sepsis.

The management of severe sepsis requires

prompt treatment within the first six hours of

resuscitation (Dellinger et al., 2008b). Experts in

critical care agree that the literature supports early

goal-directed resuscitation which has been shown to

improve survival in patients presenting to

emergency rooms with septic shock (Dellinger et al.,

2008a).

2.1 Ethical Review, Funding and Data

Ownership

The study was approved by the University of

Western Ontario Research Ethics Board and the

need for informed consent was waived. Participating

institutions submitted the study to their review

process if local approval was required. All activities

were compliant with the privacy and confidentiality

practices of the participating institutions and the

Federal and Provincial governments of Canada. Eli

Lilly Canada provided a research grant to London

Health Sciences Centre to support trial coordination,

data collection, data management and data analysis.

The investigators and sites retained control and

responsibility for data collection, analysis and

interpretation. Data is owned by and resides with

London Health Sciences Centre.

3 DECISION TREE APPROACH

In data mining and machine learning, a decision tree

is a predictive model, that is, a mapping from

observations about an item to conclusions about its

target value. In these tree structures, leaves represent

classifications and branches represent conjunctions

of features that lead to those classifications. The

machine learning technique for inducing a decision

tree from data is called decision tree learning, or

(colloquially) decision trees.

A decision tree is made from a succession of

nodes, each splitting the dataset into branches.

Generally, the algorithm begins by treating the entire

dataset as a single large set and then proceeds to

recursively split the set. Three popular rules are

typically applied in the automatic creation of

COMPARISON OF ANALYTIC APPROACHES FOR DETERMINING VARIABLES - A Case Study in Predicting the

Likelihood of Sepsis

91

classification trees. The Gini rule splits off a single

group of as large a size as possible, whereas the

entropy and twoing rules find multiple groups

comprising as close to half the samples as possible.

The algorithms construct the tree from the “top”

down until some stopping criteria is met. In our

current approach, we have used the gain in entropy

in order to determine how to best create each node

of the tree.

3.1 Entropy

In order to define information gain precisely, we

used a measure commonly used in information

theory, called entropy, that characterizes the “purity”

(or, conversely, “impurity”) of an arbitrary

collection of examples. Generally, given a set S,

containing only positive and negative examples of

some target concept (a so-called two-class problem),

the entropy of set S relative to this simple, binary

classification is defined as:

Entropy(S) = - p

p

log

2

p

p

– p

n

log

2

p

n

(1)

where p

p

is the proportion of positive examples in S

and p

n

is the proportion of negative examples in S. In

all calculations involving entropy we define 0log0 to

be 0.

One interpretation of entropy from information

theory is that it specifies the minimum number of

bits of information needed to encode the

classification of an arbitrary member of S (i.e., a

member of S drawn at random with uniform

probability).

If the target attribute takes on c different values,

then the entropy of S relative to this c-wise

classification is defined as

(2)

where p

i

is the proportion of S belonging to class i.

Note that if the target attribute can take on c possible

values, the maximum possible entropy is log

2

c.

3.2 Information Gain

Given entropy as a measure of the impurity in a

collection of training examples, we can now define a

measure of the effectiveness of an attribute in

classifying the data. The measure we will use, called

information gain, is simply the expected reduction in

entropy caused by partitioning the examples

according to this attribute. More precisely, the

information gain, Gain (S, A) of an attribute A,

relative to a collection of examples S, is defined as

(3)

where Values(A) is the set of all possible values for

attribute A, and S

v

is the subset of S for which

attribute A has value v (i.e., S

v

= {s ∈ S | A(s) = v}).

Note the first term in the equation for Gain is just

the entropy of the original collection S and the

second term is the expected value of the entropy

after S is partitioned using attribute A. The expected

entropy described by this second term is simply the

sum of the entropies of each subset S

v

, weighted by

the fraction of examples |S

v

|/|S| that belong to S

v

.

Gain (S,A) is therefore the expected reduction in

entropy caused by knowing the value of attribute A.

Put another way, Gain(S,A) is the information

provided about the target attribute value, given the

value of some other attribute. The value of

Gain(S,A) is the number of bits saved when

encoding the target value of an arbitrary member of

S, by knowing the value of attribute A.

The process of selecting a new attribute and

partitioning the training examples is now repeated

for each non-terminal descendant node in the tree,

this time using only the training examples associated

with that node. Attributes that have been

incorporated higher in the tree are excluded, so that

any given attribute can appear at most once along

any path through the tree. This process continues for

each new leaf node until either of two conditions is

met:

1. Every attribute has already been included

along this path through the tree, or

2. The training examples associated with this

leaf node all have the same target attribute

value (i.e., their entropy is zero).

Some of the variables in the data set are

continuous variables, such as temperature. These

require a somewhat special approach. This is

accomplished by dynamically defining new discrete-

valued attributes that partition the continuous

attribute value into a discrete set of intervals. In

particular, for an attribute A that is continuous-

valued, the algorithm can dynamically create a new

Boolean attribute A

c

that is true if A < c and false

otherwise. The only question is how to select the

best value for the threshold c. This is done by

selecting values for the threshold based on the

existing values of the attribute A and computing the

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

92

gain. The threshold c that produces the greatest

information gain is then chosen.

4 COMPARISON

In this section we compare the results of the decision

tree analysis to the results obtained using regression

techniques. In particular, we were interested in

which variables were identified as key in

determining sepsis in the two approaches.

4.1 Regression Analysis

Previous work had focused on the analysis of the

data using regression techniques. From a

multivariate logistic regression a number of

variables emerged as significant in the model

(computed using SAS 8.2). The model was very

accurate in being able to classify patients not likely

to get sepsis (99%) and reasonably accurate at

predicting patients that were likely to get sepsis

(66%). The variables in the model are summarized

in Table 1.

As indicated, we were interested in exploring

whether a decision tree analysis technique could

provide additional or at least complementary insight

into the regression model.

4.2 Decision Tree Analysis

The decision tree analysis yielded 9 distinct paths

that led to a determination of sepsis with high

probability. The four most frequent of the variables

associated with sepsis are shaded in Table 2 along

with all variables that appeared in one of these 9

paths.

We tested the accuracy of the tree by randomly

removing 30 patients, for whom outcomes were

known, regenerating the tree and then tested the

accuracy of the tree in predicting whether those 30

patients would develop sepsis or not. Of the 30

patients, 6 had developed sepsis. Using the decision

tree to predict the likelihood of developing sepsis for

these 6 patients, the tree predicted that 5 would

develop sepsis with a likelihood of 100% and the 6

th

would develop sepsis with a likelihood of 97%. Of

the 24 patients that did not develop sepsis, the tree

predicted their likelihood with values between 0%

and 1.7%, i.e., that it was very unlikely that these

patients would develop sepsis. Essentially, the

decision tree correctly predicted all 30 of the

patients.

Table 1: Logistic Regression Model.

Variables P value Exp(B)

Anaerobea culture

.122 .317

Abdominal diagnosis

.000 15.027

Blood diagnosis

.000 3.574

Lung diagnosis

.000 10.360

Other diagnosis

.000 8.492

Urine diagnosis

.000 7.280

Chest X-ray and purulent

sputum

.000 2.756

Gram negative culture

.047 .679

Gram positive culture

.001 .533

Heart rate >90bpm

.000 16.933

No culture growth

.000 .103

PaO2/FiO2 <250

.000 12.305

pH <7.30 or lactate >1.5

upper normal with base

deficit >5

.141 1.242

Platelets <80 or 50%

decrease in past 3 days

.000 5.665

Respiratory rate >19,

PaCO2 <32 or Mechanical

ventilation

.000 8.866

SBP <90 or MAP <70 or

Pressure for one hr

.000 9.963

Abdominal culture

.259 1.872

Blood culture

.000 2.311

Lung culture

.724 .932

Other site culture

.614 .869

Urine culture

.100 1.450

Temperature <36 or >38

.000 8.246

Urinary output <0.5

mL/kg/hr

.000 3.166

WBC > 12 or <4 or >10%

bands

.000 6.281

Yeast culture

.011 .492

Constant

.000 .000

Details on the variables and their decision points

in paths 1, 3, 4 and 9 are provided in Tables 3-6. The

variables which appear in these 9 paths of the

decision tree are highlighted in the Table 1 of the

regression model.

COMPARISON OF ANALYTIC APPROACHES FOR DETERMINING VARIABLES - A Case Study in Predicting the

Likelihood of Sepsis

93

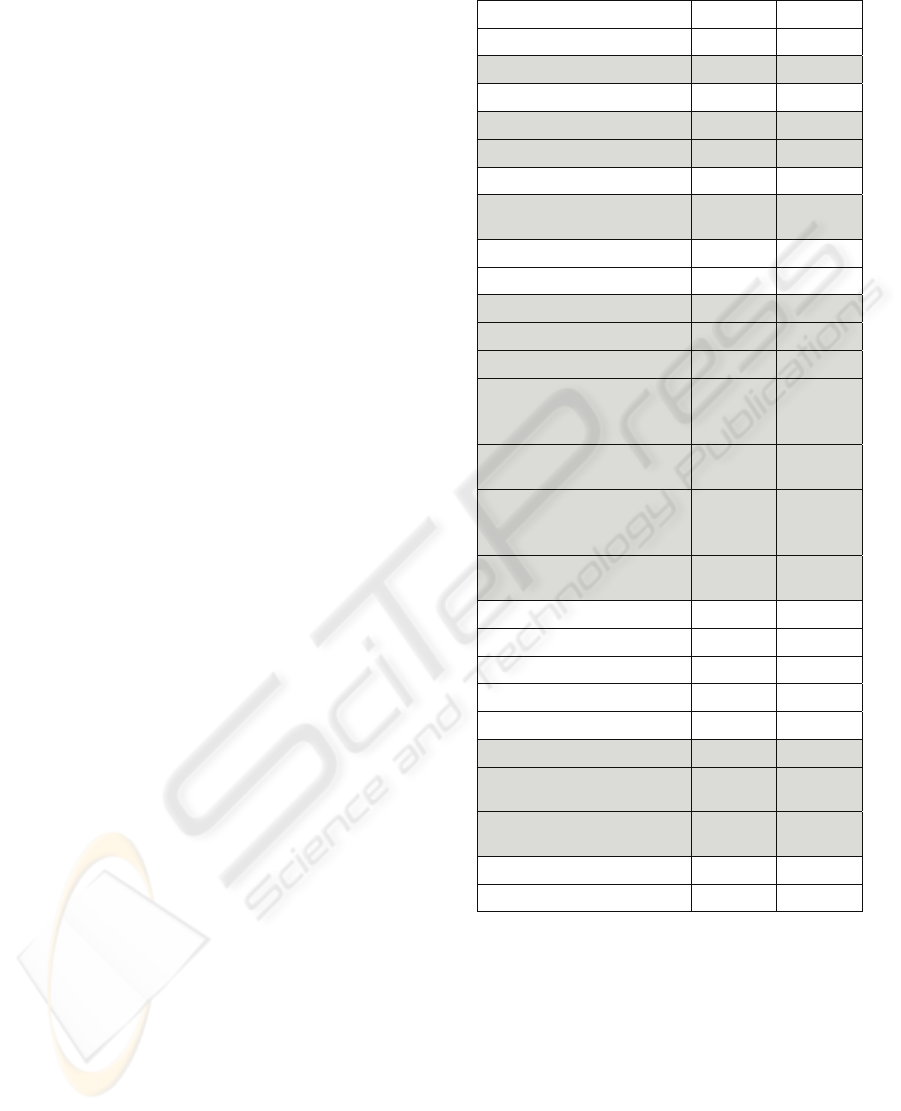

Table 2: Decision Tree Analysis.

Variables

Path1

Path2

Path3

Path4

Path5

Path6

Path7

Path8

Path9

Lung diagnosis √ √ √ √ √ √

Chest X-ray and purulent sputum √

Temperature <36 or >38 √ √ √ √ √ √ √

WBC > 12 or <4 or >10% bands √ √ √ √

No culture growth √ √ √ √ √ √

Heart rate >90bpm √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

SBP <90 or MAP < 70 or pressors for one hour √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

PaO2/FiO2 <250 √ √ √ √

Urinary output <0.5 mL/kg/hr √ √

pH <7.30 or lactate >1.5 upper normal with base

deficit >5

√ √

Respiratory rate >19, PaCO2 <32 or Mechanical

ventilation

√

√ √

Other diagnosis √ √

Abdominal diagnosis √ √ √

Platelets <80 or 50% decrease in past 3 days √ √

Note: Underlined check marks are for ‘Yes’

Table 3: Decision Tree Analysis Path-1.

Variables in the path

Platelets <80 or 50% decrease in past 3 days Yes

pH <7.30 or lactate >1.5 upper normal with base

deficit >5

No

Urinary output <0.5 mL/kg/hr No

SBP <90 or MAP < 70 or pressors for one hour No

PaO2/FiO2 <250 No

WBC > 12 or <4 or >10% bands Yes

Temperature <36 or >38 Yes

Heart rate >90bpm No

Table 4: Decision Tree Analysis Path-3.

Variables in the path

Temperature <36 or >38 Yes

Chest X-ray and purulent sputum Yes

No culture growth Yes

Lung diagnosis No

PaO2/FiO2 <250 Yes

SBP <90 or MAP < 70 or pressors for one hour No

Heart rate >90bpm Yes

Table 5: Decision Tree Analysis Path-4.

Variables in the path

Temperature <36 or >38 No

WBC > 12 or <4 or >10% bands Yes

Lung diagnosis Yes

PaO2/FiO2 <250 Yes

SBP <90 or MAP < 70 or pressors for one hour No

Heart rate >90bpm Yes

Table 6: Decision Tree Analysis Path-9.

Variables in the path

Respiratory rate >19, PaCO2 <32 or Mechanical

ventilation

Yes

WBC > 12 or <4 or >10% bands Yes

Lung diagnosis Yes

No culture growth Yes

SBP <90 or MAP < 70 or pressors for one hour Yes

Heart rate >90bpm Yes

5 DISCUSSION

First, all variables appearing in the 9 paths also did

appear in the regression model. This provides good

support for both the regression model and decision

tree result. Interestingly, urine diagnosis had

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

94

relatively high beta coefficient in the regression, but

did not appear in any of these paths of the decision

tree. However, other variables with higher beta

coefficients in the regression, such as abdominal

diagnosis, lung diagnosis, SBP and temperature,

were also important in the tree.

This has implications for practice since clinicians

want to apply models of risk at the bedside. Often it

is not feasible to collect data on 20 variables, such as

those we found in the regression or cluster and

models that are easy to use to either rule out patients

who are not at risk of sepsis or those who are at risk

would be more useful. To test any model we have to

ensure that it is reliable and valid. Here we have

shown with the 30 patient accuracy test that our tree

is reliable and it approaches 100% validity. Our

analysis also illustrates the value of multiple

methods: 1) in our analysis, regressions can be used

to provide a broad estimate of risk, and 2) a more

precise estimate in this case can be made using a

decision tree. In a separate paper, we will compare a

cluster analysis approach to a decision tree. This is

outside the scope of this paper. A valid approach for

future research is the comparison of cluster analysis,

decision trees and regression analysis.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Multiple methods of analysing clinical data provide

different perspectives on models of risk of disease.

To develop robust models researchers may want to

consider regression to get a broad perspective on the

risk and utilize decision trees to provide more

parsimonious models.

This study has several strengths. This was a

prospective observational cohort and the

determination of sepsis used standard criteria. The

large sample size provided a large number of

variables that we could use for our analyses.

Future research will now entail testing the

decision tree paths in practice to determine which

path is most reliable and valid as well as completing

a more in depth measure of the accuracy of the

regression and decision tree models. We did not

have an opportunity to test other methods such as

cluster analysis, Bayesian methods or neural

networks, which we hope to do in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Corey Hilliard for assisting

with manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical

Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for

sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of

innovative therapies in sepsis. (1992). Crit Care Med,

20, 864-874.

Alberti, C., Brun-Buisson, C., Burchardi, H., Martin, C.,

Goodman, S., Artigas, A. Sicignano, A., Palazzo, M.,

Moreno, R., Boulme, R., Lepage, E., & Le Gall, R.,

(2002). Epidemiology of sepsis and infection in ICU

patients from an international multicentre cohort study.

Intensive Care Med, 28, 108-121.

Angus, D.C., Linde-Zwirble, W.T., Lidicker, J., Clermont,

G., Carcillo, J., & Pinsky, M.R. (2001). Epidemiology

of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of

incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit

Care Med, 29, 1303-1310.

Bernard, G.R., Vincent, J.L., Laterre, P.F., LaRosa, S.P.,

Dhainaut, J.F., Lopez-Rodriguez, A. Steingrub, J.S.,

Garber, G.E., Helterbrand, J.D., Ely, E.W. & Fisher,

C.J.Jr. (2001). Efficacy and safety of recombinant

human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J

Med, 344, 699-709.

Brun-Buisson, C., Doyon, F., Carlet, J., Dellamonica, P.,

Gouin, F., Lepoutre, A. Mercier, J.C., Offenstadt, G.

& Regnier, B. (1995). Incidence, risk factors, and

outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. A

multicenter prospective study in intensive care units.

French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. JAMA, 274,

968-974.

Dellinger, R.P., Levy, M.M., Carlet, J.M., Bion, J., Parker,

M.M., Jaeschke, R., Reinhart, K., Angus, D.C., Brun-

Buisson, C., Beale, R., Calandra,T., Dhainaut, J.F.,

Gerlach, H., Harvey, M., Marini, J. J., Marshall, J.,

Ranieri, M., Ramsay, G., Sevransky, J., Thompson,

B.T., Townsend, S., Vender, J.S., Zimmerman, J.L. &

Vincent, J. L. (2008). Surviving Sepsis Campaign:

international guidelines for management of severe

sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med, 36, 296-

327.

Knaus, W.A., Draper, E.A., Wagner, D.P., & Zimmerman,

J.E. (1985). APACHE II: a severity of disease

classification system. Crit Care Med, 13, 818-829.

Knaus, W. A., Wagner, D. P., Draper, E. A., Zimmerman,

J. E., Bergner, M., Bastos, P. G., Sirio, C.A., Murphy,

D.J., Lotring, T. & Damiano, A. (1991). The

APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of

hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults.

Chest, 100, 1619-1636.

Letarte, J., Longo, C. J., Pelletier, J., Nabonne, B., &

Fisher, H. N. (2002). Patient characteristics and costs

COMPARISON OF ANALYTIC APPROACHES FOR DETERMINING VARIABLES - A Case Study in Predicting the

Likelihood of Sepsis

95

of severe sepsis and septic shock in Quebec. J Crit

Care, 17, 39-49.

Levy, M. M., Fink, M. P., Marshall, J. C., Abraham, E.,

Angus, D., Cook, D. Cohen, J., Opal, S.M., Vincent,

J.L. & Ramsay, G (2003). 2001

SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis

Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med, 31, 1250-

1256.

Martin, C., Priestap, F., Fisher, H. , Fowler R.A., Heyland,

D.K., Keenan, S.P., Longo, C.J., Morrison, T.,

Bentley, D. & Antman, N.(In Press)A prospective,

observational registry of patients with severe sepsis:

The Canadian Sepsis Treatment And Response

(STAR) Registry. Crit Care Med, (in press).

Minneci, P. C., Deans, K. J., Banks, S. M., Eichacker, P.

Q., & Natanson, C. (2004). Meta-analysis: the effect of

steroids on survival and shock during sepsis depends

on the dose. Ann Intern Med, 141, 47-56.

Pittet, D., Rangel-Frausto, S., Li, N., Tarara, D., Costigan,

M., Rempe, L., Jebson, P. & Wenzel, R.P. (1995).

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis,

severe sepsis and septic shock: incidence, morbidities

and outcomes in surgical ICU patients. Intensive Care

Med, 21, 302-309.

Rivers, E., Nguyen, B., Havstad, S., Ressler, J., Muzzin,

A., Knoblich, B., Peterson, E. & Tomlanovich, M.

(2001). Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of

severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med, 345,

1368-1377.

Salvo, I., de, C. W., Musicco, M., Langer, M., Piadena, R.,

Wolfler, A., Montani, C. & Magni, E. (1995). The

Italian SEPSIS study: preliminary results on the

incidence and evolution of SIRS, sepsis, severe sepsis

and septic shock. Intensive Care Med, 21 Suppl 2,

S244-S249.

HEALTHINF 2009 - International Conference on Health Informatics

96