BELIEFS ON INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES FROM A SINGLE

SOURCE TO BELIEFS ON THE JOINT SPACE UNDER

DEMPSTER-SHAFER THEORY

An Algorithm

Rajendra P. Srivastava

Ernst & Young Center for Auditing Research and Advanced Technology, Division of Accounting and Information Systems

The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 U.S.A.

Kenneth O. Cogger

The University of Kansas and Peak Consulting

Conifer, Colorado 80433 U.S.A.

Keywords: Approximate Reasoning, Belief Functions, Uncertainty, Evidential Reasoning, Dempster-Shafer Theory,

Joint Distribution of Beliefs.

Abstract: It is quite common in real world situations to form beliefs under Dempster-Shafer (DS) theory on various

variables from a single source. This is true, in particular, in auditing. Also, the judgment about these beliefs

is easily made in terms of simple support functions on individual variables. However, for propagating

beliefs in a network of variables, one needs to convert these beliefs on individual variables to beliefs on the

joint space of the variables pertaining to the single source of evidence. Although there are many possible

solutions to the above problem that will yield beliefs on the joint space with the desired marginal beliefs,

there is no method that will guarantee that the beliefs are derived from the same source, fully dependent

evidence. In this article, we describe such a procedure based on a maximal order decomposition algorithm.

The procedure is computationally efficient and is supported by objective chi-square and entropy criteria.

While such assignments are not unique, alternative procedures that have been suggested, such as linear

programming, are more computationally intensive and result in similar m-value determinations. It should

be noted that our maximal order decomposition (i.e., minimum entropy) approach provides m-values on the

joint space for fully dependent items of evidence.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is quite common, especially in auditing, to use one

source of evidence to form beliefs under Dempster-

Shafer theory (Shafer 1976, Srivastava & Mock

2002) on two or more variables in a decision. For

example, in an audit of the financial statements, the

auditor performs a test of confirmation of accounts

receivables where he/she sends letters to a given

number of randomly selected customers of the

company being audited asking whether they owe the

specified amount of money to the company. Such a

confirmation provides support to two assertions,

‘Existence’ and ‘Valuation’. Valuation implies that

the account balance is correctly stated and Existence

implies that the customer really exists, i.e., the

customer is not fictitious.

The level of support or

belief that the account is valued correctly, in general,

would differ from the level of belief that the

customer does really exist. These beliefs can easily

be expressed in terms of simple

support functions on

each variable, ‘Existence’ and ‘Valuation’.

However, for the purpose of propagating beliefs in a

network (Shenoy and Shafer 1990) one needs to

convert these beliefs into a belief function on the

joint space of the variables pertaining to the single

source of evidence. This paper deals with such a

conversion algorithm.

The main purpose of this article is to describe an

algorithm that converts beliefs in terms of m-values,

191

P. Srivastava R. and O. Cogger K. (2009).

BELIEFS ON INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES FROM A SINGLE SOURCE TO BELIEFS ON THE JOINT SPACE UNDER DEMPSTER-SHAFER THEORY -

An Algorithm .

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, pages 191-197

DOI: 10.5220/0001654401910197

Copyright

c

SciTePress

the basic probability assignment function (Shafer

1976), that are defined on individual variables but

have come from the same source of evidence to m-

values on the joint space of the variables. Such a

conversion is needed in order to propagate beliefs in

a network of variables and to preserve the

interdependencies among the items of evidence. In

auditing, it is quite common to use one source of

evidence to form beliefs on different variables.

Before we describe an example of the above

situation, we want to give a brief introduction to the

audit process below and show how important the

above issue is for the auditor.

The accounting profession defines auditing as (see,

e.g., Arens, Elder, and Beasley 2006):

“Auditing is the accumulation and

evaluation of evidence to determine and

report on the degree of correspondence

between the information and established

criteria (p. 4).”

There are three important steps in the above

definition that one should make a note of. The first

step, of course, is the accumulation of evidence. The

second step is the evaluation of evidence in terms of

the degree of correspondence between the

information and established criteria. The third step

deals with the aggregation of all the evidence to

form an opinion whether the information of the

entity is in accordance with the established criteria.

For the audit of financial statements (FS),

1

the

information consists of the account balances

reported on the FS and the established criteria are

the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

(GAAP). Examples of accounts on the balance

sheet would be cash, accounts receivable, inventory,

etc., and on the income statement would be sales,

cost of goods sold, expenses, etc.

In essence, the auditor accumulates sufficient

evidence related to the financial statements to

express an opinion that the financial statements

present fairly the financial position of the company

in accordance with GAAP. The question is what is

fairly? It is assumed that the FS are the repre-

sentations of management of the company. When a

company issues its FS, the management is making

certain assertions about the numbers reported in the

FS. These assertions are called management asser-

tions. The American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants through the Statement on Auditing

Standards No. 31 (AICPA 1980, see also SAS 106,

AICPA 2006) classifies these assertions into five

categories: ‘Existence or Occurrence’,

‘Completeness’, ‘Rights and Obligation’, ‘Valuation

or Allocation’, ‘Presentation and Disclosure’. It is

assumed that when all the assertions related to an

account are met then the account is fairly stated.

In order to facilitate accumulation of evidence to

determine whether each management assertion is

met, the AICPA has developed its own nine

objectives called audit objectives: Existence,

Completeness, Accuracy, Classification, Cutoff,

Detail Tie-in, Realizable value, Rights and

Obligations, Presentation and Disclosure (Arens,

Elder, and Beasley, 2006, p. 150). These objectives

are closely related to the management assertions.

For example, audit objectives: Existence,

Completeness, and Rights and Obligations, re-

spectively, correspond to management assertions:

Existence or Occurrence, Completeness, and Rights

and Obligation. The audit objectives: Accuracy,

Classification, Cutoff, Detail Tie-in, and Realizable

value relate to ‘Valuation and Allocation’ assertion

because they all deal with the valuation of the

account balance on the FS. The audit objective

‘Presentation and Disclosure’ relates to the

management assertion ‘Presentation and

Disclosure’.

Thus, in an audit, the auditor collects enough

evidence to make reasonably sure that each assertion

of an account is met and consequently each account

is fairly stated and finally making a decision on the

fair presentation of the whole FS. There are two

important points related to the above decision

process. One deals with the nature of uncertainties

associated with the audit evidence and the other

deals with the structure. Srivastava and Shafer

(1992) have argued that belief functions provide a

better framework for representing uncertainties

associated with the audit evidence than probability

theory (see also, Akresh , Loebbecke, and Scott

1988, Harrison, Srivastava, and Plumlee 2002,

Srivastava 1993, Shafer and Srivastava 1990).

Regarding the structure of evidence, it is well known

that it forms a network of variables; variable being

the accounts on the FS, the audit objectives of the

accounts, and the FS as a whole (see, e.g.,

Srivastava 1995, Srivastava, Dutta and Johns 1996,

Srivastava and Lu 2002). Thus, the process of

aggregating all the audit evidence to form an

opinion is essentially the process of propagating

beliefs in a network of variables (Shenoy and Shafer

1990, Srivastava 1995).

The network structure arises because one item of

evidence bears on more than one variable in the

network. For example, confirmations of receivables

2

bear on the following two audit objectives of the

ICAART 2009 - International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

192

account: 'Existence' and 'Valuation'. The auditor can

obtain certain level of belief from this evidence

whether the accounts receivable exist (non-

fictitious) or do not exist (fictitious) and also

whether the account balance is valued properly or

not valued properly. In general, the level of beliefs

may differ from one variable to another. For

example, in the above case, the auditor may have a

high level of belief, say 0.8, that the 'Existence' (e)

objective of accounts receivable is met but may have

a low level of belief, say 0.6, that the 'Valuation' (v)

objective of the account is met

3

. A lower belief for

the 'Valuation' objective may be due to the auditor’s

discovery of some clerical errors in the calculation

of the related sales. The above judgment of the

auditor can be written in terms of belief functions as:

Bel(e) = 0.8, Bel(~e) = 0,

Bel(v) = 0.6, Bel(~v) = 0,

The question is how should we represent the

above beliefs in terms of m-values on the joint space

of 'Existence' and 'Valuation'? Shafer, Shenoy, and

Srivastava (1988) use the concept of nested beliefs

(Shafer 1976) to achieve the above task. However,

they did not provide a general solution to the

problem, especially, for the cases where you have

both positive and negative beliefs on each variable

and also where the number of variables involved is

bigger than two. Dubois and Prade (1986, 1992,

and 1994) have discussed the above issue and shown

that one can set-up a Linear Programming problem

to find a solution. In the present article we propose

an alternative algorithm that provides a solution

without the computational effort of solving a linear

program.

4

Our algorithm is also supported by a least

squares criterion which may be applied to empirical

evidence, further encouraging its use in practice.

Furthermore, our approach provides m-values for

maximally dependent items of evidence (fully

dependent items of evidence) which is the situation

in auditing.

In the next section of the paper, we describe the

algorithm and illustrate its application to a specific

example. We follow this section with some

concluding remarks.

2 THE ALGORITHM AND AN

EXAMPLE

In order to illustrate the algorithm, let us consider a

little more complex example than the one described

in the introduction. Let us consider that the auditor

is evaluating the internal accounting control ‘batch

totals are compared with computer summary reports

for cash receipts’. This evidence bears on three

variables: existence, completeness, and valuation of

cash receipts (for more examples see Arens et al

2006). In general, the level of support from such

items of evidence for each variable may differ. For

example, in such a case, the auditor’s assessment of

the levels of support may be as follows: (1) 0.6

degree of support that the ‘existence’ objective is

met (‘e’), and no support for its negation (‘~e’), (2)

0.4 degree of support that the ‘completeness’ objec-

tive is met (‘c’), and no support that it is not met

(‘~c’), and (3) 0.3 degree of support that the

‘valuation’ objective is met (‘v’) and 0.1 degree of

support that it is not met (‘~v’). The auditor's

judgments can be written

5

in terms of belief

functions on each variable as:

Bel(e) = 0.6 and Bel(~e) = 0,

Bel(c) = 0.4 and Bel(~c) = 0,

Bel(v) = 0.3 and Bel(~v) = 0.1.

We will use this example to illustrate an algorithm

for the simple assignment of m-values to the frame

of discernment.

The Algorithm

Step 1: Express the beliefs in terms of m-values on

the individual frames of the variables. For the above

example, we will get:

m(e) = 0.6, m(~e) = 0, and m({e,~e}) = 0.4,

m(c) = 0.4, m(~c) = 0, and m({c,~c}) = 0.6,

m(v) = 0.3, m(~v) = 0.1, and m({v,~v}) = 0.6.

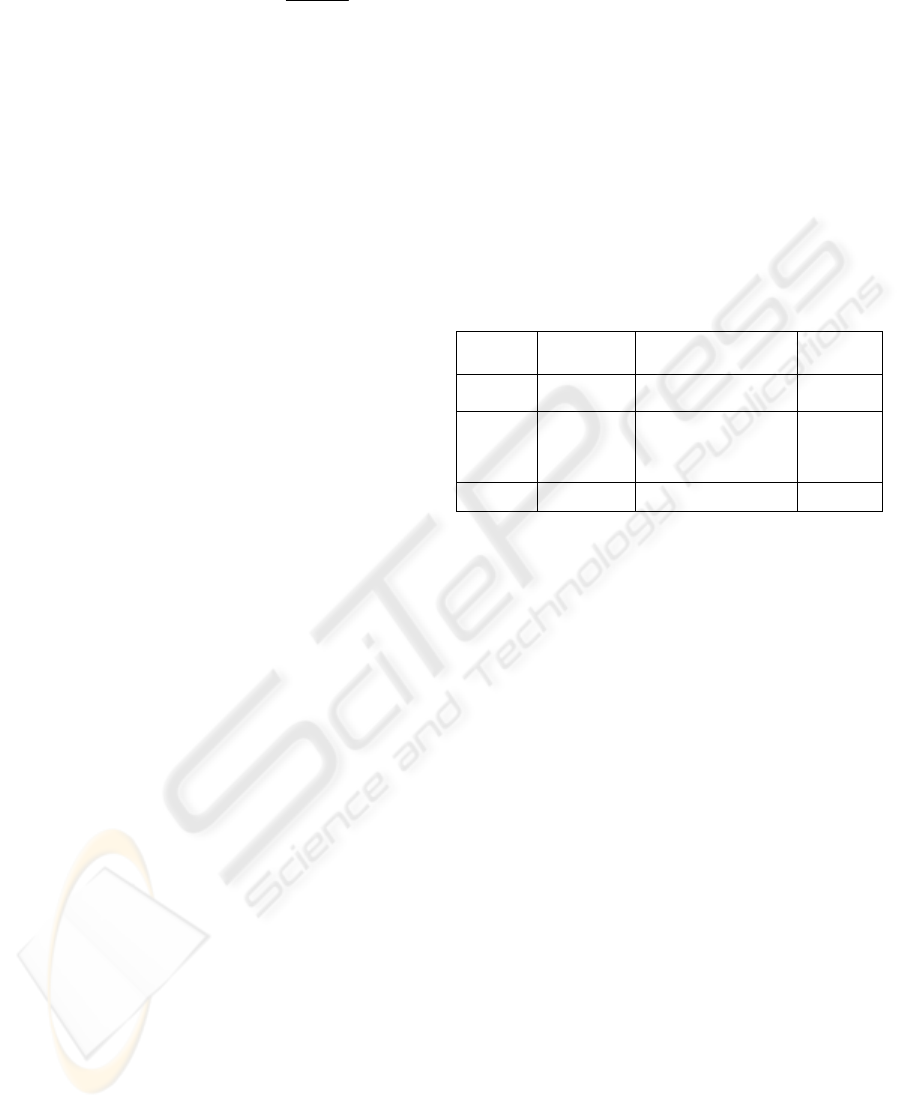

Step 2: List the m-values for each variable in a

columnar form; columns for variables, and rows for

their values (see Table 1).

Step 3: Select the smallest non-zero m-value in each

column (i.e., for each variable). These values are

written inside highlighted boxes in Table 1. These

values define the elements of the joint space.

Step 4: Select the smallest m-value among the set

obtained in Step 3. This value represents the m-

value for the set of elements on the joint space

generated by the product of individual elements

corresponding to the m-values selected in Step 3.

Step 5: Subtract the m-value obtained in Step 4 from

each selected m-value in Step 3.

Step 6: Repeat Steps 3 - 4 until all entries are zero.

BELIEFS ON INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES FROM A SINGLE SOURCE TO BELIEFS ON THE JOINT SPACE UNDER

DEMPSTER-SHAFER THEORY - An Algorithm

193

Table 1: Algorithm steps in calculation m-values on the joint space of variables.

The Resulting m-values

The m-values generated on the joint space through

the above algorithm for our example are (see Table

1).

m({ec~v, ~ec~v}) = 0.1,

m({ecv, ~ecv}) = 0.3,

m({ecv, ec~v, e~cv, e~c~v, }) = 0.6.

As we can see, the above m-values are not nested.

However, for the case of two variables with only

positive beliefs, one would obtain nested m-values

as used by Shafer, Shenoy, and Srivastava (1988).

If we marginalize the above m-values on the

individual variable space then we do get the beliefs

that the auditor had estimated. The above approach

is valid even for non-binary variables. Of course, m-

value assignments with this property are not unique.

However, the merit of this particular assignment

algorithm may be argued in two ways.

First, the algorithm is computationally economic

relative to other approaches such as linear

programming. Moreover, it is possible to show that

the present algorithm produces the same assignments

as linear programming under certain conditions.

Second, we can show that this algorithm

produces an assignment of m-values which

minimizes the squared differences between each

pairwise assignment and the consequent belief value

in the case of two variables.

As Dubois and Prade (1986) discuss, the

existence of criteria-dependent solutions to the m-

value assignment problem is not surprising.

However, the computational simplicity of the present

algorithm suggests its consideration in practice.

3 MAXIMAL ORDER

DECOMPOSITION

The creation of m-values with the algorithm

described in the previous section is computationally

efficient. In this section, we wish to explore the

mathematical properties of the algorithm. It is

difficult to develop insights in the general case, so

we restrict our attention to the case of two variables.

This is similar to the approach taken by Dubois and

Prade (1986).

Consider the two variables c and v from the

previous section. m-values on their values are easily

summarized in :

Table 2: M-values for two variables.

Var v ~v (v,~v) m

C 0.3 0.1 0.0 0.4

~c 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

(c,~c) 0.0 0.0 0.6 0.6

M 0.3 0.1 0.6

Many allocations of these m-values are possible

consistent with the row and column totals. The

allocations in Table 2 from our algorithm can be

shown to have some very attractive properties.

For comparative purposes with other

assignments, we may calculate two statistics. First,

the entropy,

Entropy ln

ii

pp

=−

∑

and second, the

value of the chi-square statistic for testing the

Step Variable m-value Variable m-value Variable m-value Result

1 e 0.6 c 0.4 v 0.3

~e 0.0 ~c 0.0 ~v 0.1

{e,~e} 0.4 {c,~c} 0.6 {v,~v} 0.6 m({ec~v,~ec~v})=0.1

2 e 0.6 c 0.3 v 0.3

~e 0.0 ~c 0.0 ~v 0.0

{e,~e} 0.3 {c,~c} 0.6 {v,~v} 0.6 m({ecv,~ecv})=0.3

3 e 0.6 c 0.0 v 0.0

~e 0.0 ~c 0.0 ~v 0.0

{e,~e} 0.0 {c,~c} 0.6 {v,~v} 0.6 m({ecv,ec~v,e~cv,e~c

~v})=0.6

4 e 0.0 c 0.0 v 0.0

~e 0.0 ~c 0.0 ~v 0.0

{e,~e} 0.0 {c,~c} 0.0 {v,~v} 0.0 Stop

ICAART 2009 - International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

194

hypothesis of independence,

2

2

()OE

E

−

Χ=

∑

, where

O is the observed table value and E is the table value

expected if rows and columns were independent. In

the case of independence, table values would be

assigned by multiplying row and column marginal

totals. For our algorithm,

Entropy=-0.3ln(0.3) -0.1ln(0.1) -0.6ln(0.6) = 0.8979,

2

Χ=(0.3-0.12)

2

/0.12 + . + (0.6-0.36)

2

/0.36 = 1

If m-values were allocated according to

independence, we obtain Entropy = 1.572 and X

2

=

0.0.

The entropy for a joint distribution of two

random variables E(X,Y) is known to satisfy E(X,Y)

>= E(X), E(X,Y) >= E(Y), and E(X,Y) <= E(X) +

E(Y), with the last being an equality if and only if X

and Y are independent random variables. In the

above table, denote the entropy for the rows and

columns by E(C) and E(V). It is easily seen that

E(C) = 0.673 and E(V) =0.898. In this example, our

algorithm produces a joint entropy equal to that of

the columns which, in turn, is the smallest possible

joint entropy consistent with the row and column

totals. The assignment of m-values via the

independence assumption, alternatively, yields a

joint entropy that is the highest possible, namely the

sum of E(C) and E(V).

Thus our algorithm, when compared with

independent allocation, minimizes entropy and

maximizes the chi-square statistic. Since entropy is

a measure of disorder, we are maximizing order, and

hence we term our approach, Maximal Order

Decomposition. Thus we have a clear distinction

with the Dubois and Prade algorithm, which is based

on linear programming and maximizes entropy. Thus

we have two competing approaches, that of

independence, which is equivalent to maximum

entropy, and our algorithm, which results in

minimum entropy. In our case, the two sets of m-

values originate from the same source, so we cannot

assume independence. The minimum entropy

approach provides m-values for the more realistic

fully dependent case.

We believe ours is clearly superior on

computational grounds, making it the algorithm of

choice in large complex systems. Note also that

while independence requires simple multiplication to

allocate m-values, the number of nonzero elements

in the frame grows exponentially with the number of

variables. In the two-variable case, our frame has

only three nonzero m-values, while independent

variables would have nine. With 25 variables, our

approach would yield 25 nonzero m-values, while

independent variables would require 3

25

= 8.5E11

nonzero assignments.

A proof that our approach maximizes chi-square

and minimizes entropy is unattainable in the general

case, but a proof is available for the simplest 2 x 2

case, which was considered by Dubois and Prade.

We will use their notation for ease of comparison.

First, consider assigning m-values of

α

and

β

to

variable a and b. An assignment is defined by X

AB

,

X

A

, X

B

, X

w

, as in the table below:

Table 3: Feasible assignment of m-values.

Variabl

e

b ~b m-value

a

AB

X

AB

X

α

−

α

~a

AB

X

−

β

1

AB

X

αβ

−−+

1

α

−

m-value

β

1

β

−

The minimum chi-square statistic is zero when

X

AB

= *

α

β

. The maximum chi-square statistic can

be found by maximizing

2 2

()/((1)(1))

AB

X

αβ

αα

ββ

Χ= − − −

subject to the constraints

max(0,

1

α

β

+

− )

AB

X

≤

≤ min( ,

α

β

).

Clearly the maximum will occur at either the upper

or lower bound on X

AB

, and we may simply examine

all (four) possible orderings of the m-values to

verify that our algorithm maximizes chi-square. We

will not repeat the proof for all possibilities. The

interested reader may find it informative to do so,

however. As an example of one of the possibilities,

suppose that

11

α

ββα

≤

≤− ≤− . Our algorithm

produces the solution corresponding to X

AB

=

α

. For

this particular ordering of m-values, the previously

stated limits become 0

AB

X

α

≤

≤ . Maximum chi-

square occurs at X

AB

=

α

if and only if

22

()(0)

α

α

β

α

β

−≥− which is true for this chosen

case. Similar arguments hold for any permutation of

the m-values, and therefore our Maximum Order

Decomposition Algorithm maximizes the chi-

square statistic for any given set of m-values.

To also prove that the algorithm minimizes

BELIEFS ON INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES FROM A SINGLE SOURCE TO BELIEFS ON THE JOINT SPACE UNDER

DEMPSTER-SHAFER THEORY - An Algorithm

195

entropy, consider any arbitrary allocation as a

function of X

AB

. After writing the expression for

Entropy as a function of X

AB

we note that the same

upper and lower bounds as for the chi-square

calculation must be preserved. We also note that

Entropy is (1) concave downward and (2) has a

derivative of zero only at X

AB

=

α

β

. This point is

therefore a global maximum for E, and is identical to

the minimum chi-square point. The minimum

entropy therefore must be at either the upper or

lower limit on X

AB

as was the case previously

considered. The proof that our algorithm minimizes

E proceeds in the same way as before. For each of

the (four) possible m-value orderings, we can prove

that our assignment minimizes E and coincides with

the upper or lower limit on X

AB

.

Our algorithm therefore maximizes chi-square

while minimizing entropy. Because of these

properties, we may refer to it as the Maximal Order

Decomposition Algorithm. We should note also

that in the simplest case examined by DuBois and

Prade, our assignments are identical to theirs.

4 SUMMARY AND

CONCLUSIONS

We have described a sequential algorithm for the

assignment of m-values to subsets of the frame of

discernment that are consistent with an overall

assignment of beliefs to individual variables. While

many such assignments are possible, our algorithm

is computationally simple, completely general, and is

supported by objective chi-square and entropy

criteria. In the simplest case of two variables, this

algorithm produces an assignment identical to that of

more complicated algorithms.

FOOTNOTES

1. There are several types of audit: the audit of

financial statements of a company, compliance

audit, income tax audit, operational audit, and

assertion audit. In principle, they are all the

same; they all involve collection, evaluation,

and aggregation of evidence to form an opinion.

However, the nature of assertions and the

corresponding items of evidence may differ

from one type of audit to another. In this article,

we use examples from the audit of financial

statements. Financial Statements consist of a set

of four statements in the USA: balance sheet,

income statement, statement of cash flow, and

statement of retained earnings. (see, e.g., Arens,

Elder, and Beasley 2006, for details on the

definitions of various types of audit).

2. In auditing accounts receivable, auditors usually

send letters of confirmation to some selected

customers of the client to verify the following;

(1) whether they owe any money to the com-

pany, and (2) the amount they owe is the

amount given in the confirmation letter.

3. As a convention, we will use the first letter in the

lower case in the name of a variable to represent

the values of the variable. For example, for

‘Existence’, we will use ‘e’ and ‘~e’, respec-

tively for the two values that the objective is

met, and not met.

4. The set of m-values on the joint space that yields

the desired beliefs on individual variables is not

unique.

5. It should be pointed out that this judgment of the

auditor can not be easily represented in terms

probabilities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants of

the AI and E&Y CARAT Workshop, School

Business, The University of Kansas, for their

valuable comments.

REFERENCES

Akresh, A. D., J. K. Loebbecke, and W. R. Scott, Audit

approaches and techniques. Research Opportunities in

Auditing: The Second Decade, edited by A. R. Abdel-

khalik and Ira Solomon, Sarasota, FL: AAA:13-55,

1988.

Arens, A. A., R. J. Elder, and M. Beasley, Auditing and

Assurance Services: An Integrated Approach,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2006.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants,

Statement on Auditing Standards, No, 31: Evidential

Matter, New York: AICPA, 1980.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Audit

Evidence. Statement on Auditing Standards. No. 106.

New York, NY: AICPA, 2006.

Dubois , D., and H. Prade, The Principles of Minimum

Specificity as a Basis for Evidential Reasoning.

Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems (Bouchon

ICAART 2009 - International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

196

B., Yager R. R. eds.), Springer-Verlag, LNCS,

Volume No. 286:75-84, 1986.

Dubois , D., and H. Prade, Evidence, Knowledge, and

Belief Functions. Internal Journal of Approximate

Reasoning, Vol. 6: 295-319, 1992.

Dubois , D., and H. Prade, Focusing versus Updating in

Belief Function Theory. Advances in the Dempster-

Shafer Theory of Evidence, (Yager R.R., Kacprzyk J,

and Fedrizzi M. eds.), Wiley: 71-95, 1994.

Harrison, K., R. P. Srivastava, and R. D. Plumlee. 2002.

Auditors’ Evaluations of Uncertain Audit Evidence:

Belief Functions versus Probabilities. In Belief

Functions in Business Decisions, edited by R. P.

Srivastava and T. Mock, Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg,

Springer-Verlag Company: 161-183.

Shafer, G., A Mathematical Theory of Evidence, Princeton

University Press, 1976.

Shafer , G., and R. P. Srivastava, The bayesian and belief-

function formalisms: A general perspective for

auditing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory

9 (Supplement):110-48, 1990.

Shafer, G., P. P. Shenoy, and R. P. Srivastava. Auditor's

Assistant: A knowledge engineering tool for audit

decisions. Proceedings of the 1988 Touche

Ross/University of Kansas Symposium on Auditing

Problems. Lawrence, KS: School of Business,

University of Kansas:61-84, 1988.

Shenoy , P. P., and G. Shafer. Axioms for probability and

belief-function propagation. Uncertainty in Artificial

Intelligence 4, edited by R. D. Shachter, T. S. Levitt,

L. N. Kanal, and J. F. Lemmer, Amsterdam, North-

Holland: 169-98, 1990.

Srivastava , R. P., Belief Functions and Audit Decisions.

Auditors Report, Vol. 17, No. 1: 8-12, Fall 1993.

Srivastava , R. P., The Belief-Function Approach to

Aggregating Audit Evidence. International Journal of

Intelligent Systems, Vol. 10, No. 3:329-356, March

1995b.

Srivastava , R. P., Dutta, and R. Johns, An Expert System

Approach to Audit Planning and Evaluation in the

Belief-Function Framework. International Journal of

Inteligent Systems in Accounting, Finance and

Management, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1996, pp. 165-183.

Srivastava, R. P. and H. Lu, Structural Analysis of Audit

Evidence using Belief Functions, Fuzzy Sets and

Systems, Vol. 131, Issues No. 1, October: 107-120,

2002.

Srivastava, R. P. and T. Mock, Belief Functions in

Business Decisions, Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg,

Springer-Verlag Company, 2002.

Srivastava, R. P., and G. Shafer, Belief-Function Formulas

for Audit Risk. The Accounting Review, Vol. 67, No.

2:249-283, April 1992.

BELIEFS ON INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES FROM A SINGLE SOURCE TO BELIEFS ON THE JOINT SPACE UNDER

DEMPSTER-SHAFER THEORY - An Algorithm

197