Data Collection Methods for Task-based Information

Access in Molecular Medicine

Sanna Kumpulainen

1

, Kalervo Järvelin

1

, Sami Serola

1

, Aiden R. Doherty

2

Daragh Byrne

2

, Alan F. Smeaton

2

and Gareth J. F. Jones

2

1

Department of Information Studies, University of Tampere, Finland

2

CDVP & CLARITY: Centre for Sensor Web Technologies, Dublin City University, Ireland

Abstract. An important area of improving access to health information is the

study of task-based information access in the health domain. This is a

significant challenge towards developing focused information retrieval (IR)

systems. Due to the complexities of this context, its study requires multiple and

often tedious means of data collection, which yields a lot of data for analysis,

but also allows triangulation so as to increase the reliability of the findings. In

addition to traditional means of data collection, such as questionnaires,

interviews and observation, there are novel opportunities provided by

lifelogging technologies such as the SenseCam. Together they yield an

understanding of information needs, the sources used, and their access

strategies. The present paper examines the strengths and weaknesses of the

traditional and the more novel means of data collection and addresses the

challenges in their application in molecular medicine, which intensively uses

digital information sources.

1 Introduction

The production of digital information in molecular medicine has huge dimensions.

Effective management of, and access to, this information requires that tools are

developed to serve work tasks in the domain. Task-based information access is

recognized as a significant context for developing information retrieval (IR) systems

[4], [7], [8]. Contrary to the general Web environment, the task-based context

necessitates the study of task performers (users), their tasks and the organizational and

social context of task performance. In this context, it is no longer sufficient to perform

plain search engine-side analysis of logs and clicks even if such data were abundant;

one needs to learn about the tasks, the information goals, how information is

approached and used, and how access operations are generated. Understanding the

current state of information access in molecular medicine helps to find the needs in

mobilizing health information.

Due to the complexities of the task context in molecular medicine, its study

requires multiple and often tedious means of data collection. Traditional means of

data collection include questionnaires, interviews, diaries, and observation [4]. Log

analysis is a more recent means and very popular in Web information retrieval

Kumpulainen S., Järvelin K., Serola S., Doherty A., Byrne D., Smeaton A. and Jones G. (2009).

Data Collection Methods for Analyzing Task-based Information Access in Molecular Medicine.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Mobilizing Health Information to Support Healthcare-related Knowledge Work, pages 49-58

DOI: 10.5220/0001814300490058

Copyright

c

SciTePress

research. An even more recent tool is photographic surveillance of the task

performer’s environment through a wearable camera carried by the study subjects. In

addition to analysing traditional means of data collection, the present study analyses a

modern logging system, the PLogger, and a wearable camera, the SenseCam, as tools

for data collection for studies on task-based information access in molecular

medicine.

The PLogger, developed at the University of Tampere, Finland [5] is a tool that

logs a Web browser's search history on an external database server. It was developed

as a research tool to collect history logs as a time ordered list of URL-addresses. It

allows the subjects to edit their logs before submitting them to the researcher.

The SenseCam, developed by Microsoft Research in Cambridge U.K. [3] is a small

wearable camera that is worn around the neck. This camera passively captures images

from the perspective of the user. Images are taken quite frequently (approximately 3

per minute), thus an extensive visual diary of one’s day is recorded. In a typical day a

user will capture 2,000 images.

Employed together, these data collection methods yield a lot of data for analysis,

but also support triangulation to achieve a comprehensive understanding of

information access in molecular medicine. The present paper examines the strengths

and weaknesses of the traditional and the more novel methods of data collection and

addresses the challenges in their application in the study of task-based information

access. In particular, we focus on how observation, logging and the SenseCam affect

the subjects’ behavior and support triangulation for greater reliability. We draw our

data collection experiences mainly from an empirical study on information access in

molecular medicine [6]. A part of this study was based on Web questionnaires,

interviews, shadowing, logging and use of the SenseCam at an anonymous research

institute in Finland. The following treatise reflects the lessons learned in applying the

data collection methods and seeks to contribute an understanding on the needs for

multiple methods and on the challenges involved in applying them.

The paper is structured as follows. Sections 2-6 discuss the data collection methods

individually and Section 7 discusses triangulation. Conclusions are given in Section 8.

2 Web Questionnaires

To start the empirical study, we distributed a Web questionnaire in summer 2007 to

the respondents to find out about the information environment of the study subjects,

the kinds of tasks they conducted, their publication plans, and difficulties experienced

in information access. The questionnaire was designed in co-operation with a senior

group leader working at the target institute. An invitation and motivation letter was

sent by e-mail to the researchers of the institute, then three reminders followed by

personal emails to some researchers. As often is the case with Web questionnaires, it

was challenging to raise the response rate above 50%.

In general, we may echo the known benefits of questionnaires which are (a)

reaching large groups of people quickly and simultaneously, (b) ease and economy of

collecting the data, (c) obtaining data that is structured and easy to handle, and (d)

supportive of statistical analysis. However, we also experienced the known challenges

of questionnaires, including (a) low response rates due to lack of motivation, (b)

50

respondents not understanding the rationale behind the questionnaire, (c) respondents

misinterpreting questions, (d) respondents providing unexpected or incomplete

answers to specific questions, and (e) difficulty on getting answers to why questions

in particular.

It is a challenge to try to penetrate into an unfamiliar community – molecular

medicine – as an outsider through a questionnaire. The questions tend to come from

the investigator’s world, resulting in problems of motivation and understanding. The

subjects may have difficulty in correctly remembering difficulties experienced in

information access, and may well present a rationalized view of their task

performance or problems encountered therein – which actually happened in our case.

Their recollections regarding their behavior differed from their real behavior. These

issues hardly surprised us.

Nevertheless, through extensive effort we got an overview and hints on what to

focus on, but certainly did not learn what tasks the respondents perform, nor much

about their information access.

3 Interviews

Interviews can address some of the problems associated with questionnaires. Their

known strengths, in general, include: (a) the possibility of immediate resolution of

ambiguities, (b) interviewing is focused: one need not “see” everything like when

observing, (c) interviewing supports the why questions, (d) the researcher obtains a

personal contact while access to the field is easier than when observing. Interviews

can be more or less structured. In semi-structured interviews the interview guide

keeps one on track but still allows one to collect unlimited qualitative data.

However, interviews are (a) open to bias and problems of personal chemistries, (b)

opinions regarding behavior are not the same as actual behavior, and (c) the

respondents may not correctly remember answers to questions. Further on the

downside, interviews are quite insufficient for learning about task performance /

information access. One rather hears ex post facto accounts of task performance: the

real problems and discomforts are not necessarily reported if remembered.

In our project, to get further insight into the work tasks and information access

after the questionnaire, we did three kinds of semi-structured interviews. Firstly, two

researchers were interviewed to complement the questionnaire (reported in [6]). A

recent critical event (an information access episode) was reviewed during these

interviews. Secondly, the leaders of two research groups were interviewed to find

suitable shadowees. Thirdly, the six selected shadowees were interviewed at the

beginning of the shadowing to find out about their research processes, current tasks

and their perceptions of their information access. These turned out to provide much

insight for the investigator.

4 Observation and Shadowing

The main part of our empirical study was based on shadowing six molecular medicine

51

researchers for an average of 24 hours per person over periods from three to eight

weeks; logging their Web interaction through the ProxyLogger for four to nine weeks

each; and recording their activities by SenseCam for 10 work days each (with one

subject only for 2 days). After the initial interview, the six researchers were shadowed

when performing their normal tasks at their work places. However, as we wanted to

focus on their information access, the shadowing sessions were agreed with the

shadowees. The investigator followed them closely, clarified any unclear actions

through verbal exchanges and took field notes. Most of the time logging took place

simultaneously and the SenseCam periods partially overlapped with shadowing. In

all, shadowing took place over a period of six months (2007-08).

Shadowing provided very valuable data. It happened in naturalistic settings and

supported the investigator in constructing the shadowees’ normal tasks. They were

performing realistic tasks under familiar conditions and employing their current

practices and orientations. Any problems in task performance could be immediately

observed. When clarification was needed immediate interaction was possible. This

permitted the study of activities that people may be unable (e.g. due to forgetting) or

unwilling to report (failures). Indeed, the interaction of tasks, information goals and

the integrated use of various access tools became understandable. This is not possible

through other means of data collection unless the investigator is a domain specialist.

However, there were problems as well. The investigator, not being a domain

specialist sometimes had difficulty in understanding task performance. This may have

led to misinterpretations and also to verbal exchanges disturbing task performance,

deviating from the normal process. The shadowees certainly were aware of being

shadowed and may have affected behavior and task performance. However, nearly all

shadowees appeared to become comfortable with the situation in a couple of days.

The greatest challenge of shadowing is its time-consumption, both in the act and

afterwards in analyzing the observations. Another issue is frustration: the shadowees

could not always perform their tasks because of problems with tools, or lack of

feedback. There were also interpersonal dependencies between shadowees and others:

if someone else was not delivering her results a shadowee’s task was sometimes

blocked. Last but not least, trust-building and ethics of reporting were also issues in

shadowing. Some shadowees enquired about the use of the results (“Is this some sort

of management control effort?”).

The investigator needed to stay alert and disciplined during the shadowing

sessions, but nonetheless the situations could change so rapidly, that it was difficult to

quickly maintain the field notes. The automatic data collection helped in these cases

to complete the incomplete shadowing data, even when the observer had been present.

Some of the challenges of shadowing could be circumvented by automatic tools

like PLogger and SenseCam. Being automatic, they do not require the investigator’s

presence thus avoiding some of obtrusiveness and facilitating the extension of the

data through much longer collection periods.

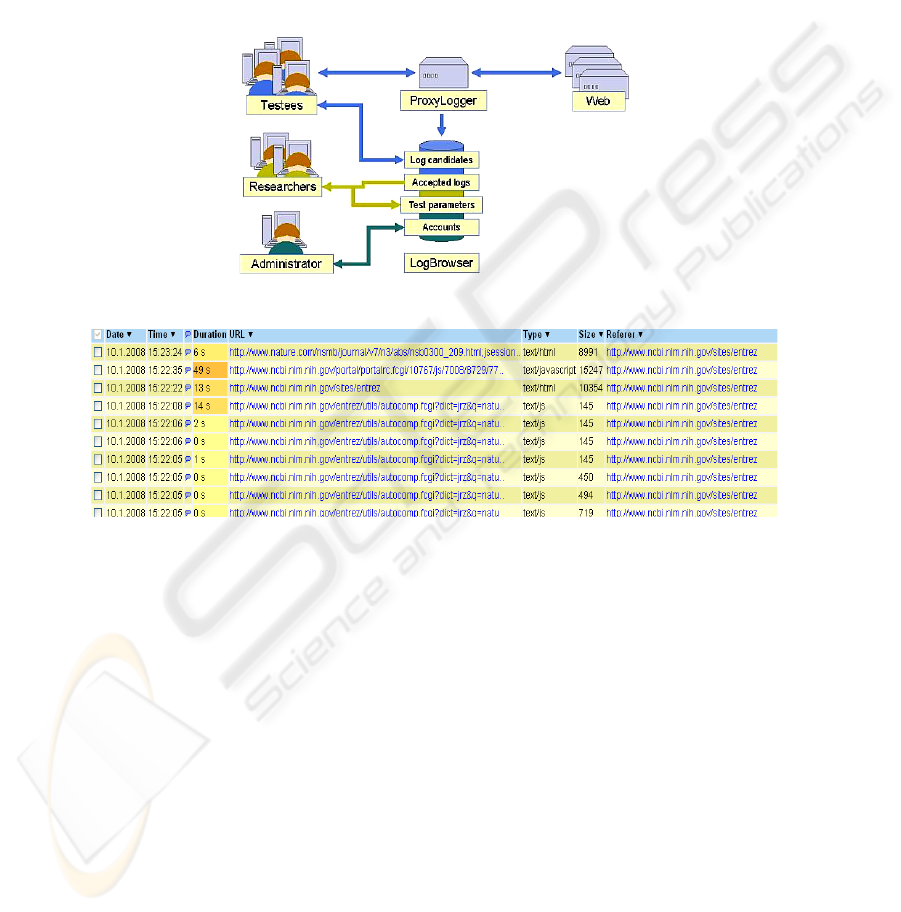

5 PLogger

PLogger is a tool for collecting visited http URLs in chronological order and

analyzing them. It consists of two components, the ProxyLogger for logging the

52

URLs and the LogBrowser for analysis of the logs (Fig. 1). The subjects are able to

edit their logs via LogBrowser (see sample log in Fig. 2) before submitting them to

the investigator. This is an important feature for user acceptance of logging while not

all subjects were sensitive about their logs.

PLogger is installed on a proxy server and the subjects’ browsers are set to direct

all traffic through it. The logs are stored in a relational database (PostgreSQL). When

a subject starts his/her browser, PLogger reminds that logging is starting as well.

While working, the subject may turn it on and off– again a feature increasing user

acceptance.

Fig. 1. PLogger architecture.

Fig. 2. PLogger’s LogBrowser (a subset of columns).

The strengths of PLogger include:

• Web interaction logs reveal requested files, search strategies, dwelling time per

page, search keys and parameters.

• The participants can easily turn logging on and off and edit their logs before

submitting them. This helps in building trust and gaining acceptance.

• Lots of data about Web information access is easily collected.

• The logs are stored in a database, which allows them to be queried for various

analytical needs. Ordinary digital screen capture would not support this – providing

only digital video.

• It doesn’t require any additional effort on the part of the subject.

In total we collected a log of 24,360 lines of Web interaction for the six subjects

(ranging from 3,130 to 5,760 lines per subject).

Despite its strengths, the PLogger poses several challenges in data collection. First

of all, it was still an experimental tool and therefore had usability problems. In

53

particular, it sometimes behaved more like a “proxy blocker” – preventing access to

some services either altogether or slowing down access critically. This problem was

circumvented by installing the Plogger server within the research institute’s domain.

These usability issues had interesting consequences on the subjects’ behavior.

Some used another computer (not logged) for certain tasks, while others started

another (non-logged) browser. Some just turned the PLogger off – not due to sensitive

Web use but for convenience of work. We believe that it is of key importance to

control the functioning and use of any logging tools no matter how well tested they

may be. While an advanced logging tool may also provide much functionality – an

investigator using it for the first time, and for one study, may find learning its

effective use overwhelming. Therefore they should be very intuitive to use.

While much of the internationally available research data for molecular medicine is

provided through http, this does not cover all protocols, e.g., direct access between

Unix platforms through ssh. Screen capture as digital video would show this, but the

result is not easily logged in a database. Moreover, because PLogger recorded only

URLs using http, some of the secured services using https were not recorded. Finally

the data presented further challenges. One collects masses of very “dirty data”: there

is a lot of noise, uninformative log records, especially when frame-based Web pages

are accessed. These were hard to filter but resulted in 30% reduction in the amount of

data for further analysis. The logs alone are clearly insufficient for the analysis of

information access: it is impossible to tell what one searches based on the log alone

because the target information and the handle used to locate it may have no obvious

semantic connection that the investigator could figure out. Similar handles are used

for quite different goals – and in the log the investigator only sees the handles. Even

an obvious known item search (e.g., for a homepage) may in fact be an unknown fact

search (for an email address).

6 SenseCam

The SenseCam is a wearable camera that passively captures images from the user’s

perspective. Additionally it captures sensor values such as: temperature, light levels,

movement, and passive infrared information. The battery allows the camera to run all

day, and can then be charged overnight.

In our work the subjects captured SenseCam images totaling a 52 day period

(equating to approximately 72,000 images). To help review this vast collection of data

we segmented the users’ data into distinct events or activities [2], and presented them

through an event-based browser (illustrated in Fig. 3). The calendar allows the

investigator to browse to day of interest. A vertical column then displays each event

for the day. Once an event is selected, all images from the event are shown on the

right of the screen.

Task-observation studies normally require intensive effort, commitment and

resources [1]. The SenseCam presents a novel medium in which to capture

observational data and reduce the burden on both the investigator and the subject(s).

As the SenseCam is a fully automated capture system it removes the implicit need for

an observer to be present at all times. As in this study, subjects may be shadowed

initially for a short period after which they are instrumented with the SenseCam for a

54

longer period. The SenseCam allowed observation of tasks for an extended period

without the resource commitment normally associated with shadowing, proving itself

to effective in eliciting high-level task details. The SenseCam is additionally non-

intrusive into task performance. It allows the capture of points of interest without

distracting users by temporarily abandoning their current activity.

Fig. 3. SenseCam browser.

SenseCam images, as a visual account of tasks a participant carried out, can be

very useful within post-observation discussions and/or follow-up interviews. Using

our tool (see Fig. 3) the image data can be segmented into discrete ‘events’ and

presented as a grouped set of images. As these images are temporally consistent they

will often ‘storyboard’ the progression of a task. They additionally allow both the

subject and investigator to return to events, and facilitate discussion regarding task

flow.

The use of the SenseCam in observational fieldwork is, however, not without its

limitations. While the SenseCam is less intrusive than shadowing, users are still

nevertheless aware of the presence of this device and hence do not act in a completely

natural manner. Although after a few days the user becomes much less conscious of

it. This effect is not limited to the wearer – others in the vicinity reported feeling as if

“under surveillance”. As a result, it was necessary to spend time reassuring the work

group of the benefits offered by the SenseCam recordings.

The review of SenseCam images is almost solely based on a visual analysis of the

subject’s day. Therefore in tasks where the subject is walking between different

scenes (or to a number of distinct areas within a scene), a review of the SenseCam

images is very helpful. However the SenseCam images are not suited to determining

the information need of subjects who spend large amounts of time at the same

desk/PC everyday. Due to the fast paced nature of expert computer-based tasks the

SenseCam will often miss the subtleties, and/or specifics of interaction. As such,

computer-based interactions can only be ‘gisted’ using the SenseCam.

There are other practical problems associated with the SenseCam. These include:

users forgetting to turn the device on early in the morning; leaving the lens cap on;

photos fully or partially obscured by clothing such as a jacket; and up to 40% of the

time the device may capture poor quality or unusable images [1]. Finally we feel that

the SenseCam can’t replace shadowing in its current form as the communication

55

between shadower and shadowee is essential to understanding the task. However,

even though the SenseCam is currently a prototype and many of its limitations may be

resolved in the future, we believe it can already effectively complement shadowing.

7 Discussion

Task-based information access is a complex phenomenon where context

characteristics (the organization, its culture, and its information environment), the task

performer’s traits (knowledge, experience, personality), and the varying tasks

themselves affect information access. The design of novel information access systems

for molecular medicine should learn from the task performers’ experiences and from

technological possibilities in the domain. Learning from the experiences requires data

collection based on multiple methods and triangulation of the findings because no

single method is reliable and sufficient. Indeed, in the present study we learned that:

• Shadowing turned out to be invaluable in understanding the task context and

interpreting the information goals that lead to specific logged actions, or the variety

of activities yielding quite similar SenseCam photos. Shadowing was however very

time-consuming, and thus expensive, and to some degree intrusive and affected by

personalities. It was often impossible to capture quick interactions in information

access just by observing.

• Web access logging using the PLogger registered such interactions in detail.

Logging was also possible over extended periods yielding lots of data on

information access in collections of bio-medical data and literature. It revealed that

much access to literature (PubMed) happened through links or automatic queries

from biological databases – while the subjects reported that they used PubMed

directly. It would have been quite difficult to figure out the what and why from the

logs alone, without an understanding on the researchers’ work tasks. Although

PLogger was meant to be non-intrusive, its slowness sometimes caused behavior

that biased the data: PLogger was turned off, another unlogged browser was

launched, or another computer was used. The subjects were working with multiple

unpredictable services which made the predefining of filters for focused logging

difficult. Therefore the logs contained much noise to be filtered out afterwards.

Finally, while the Web is the main channel for information access, it alone does not

cover all digital access.

• Photo capture using the SenseCam was very useful in mapping out the daily

activities of the subjects over extended periods to build an understanding of

ordinary working days and events – and anything unforeseen. This guides the

investigator in organising shadowing, in focused interviewing about recent events,

e.g., unlogged information access. However the SenseCam was not very useful

when the subject was just sitting in front of a screen. The number of photos per day

is overwhelming, but automatic event detection [2] was an essential help.

However, tuning the event detection parameters did not always succeed perfectly.

As photos do not speak for themselves and voice was not recorded, interpretation

needs to come from the investigator’s understanding based on other methods.

Sometimes the SenseCam was forgotten on one’s desk or turned off.

56

As we can see, each method of data collection was incomplete and insufficient and

had potential biases. However, when used together they triangulate quite successfully.

More methods nevertheless mean more work, thus challenging the economics of the

study. While the automatic methods allow extended data collection, they cannot

replace shadowing unless the investigator is thoroughly acquainted with the task

processes (or they are very repetitive). However they indicate what is typical in the

data and thus allow the investigator to extrapolate from a limited sample of

thoroughly analyzed information access episodes.

Automatic experimental data collection tools may have usability problems when

applied in new environments. These include slowing down or entirely blocking web

access (PLogger), and suboptimal event detection or failing to output some days’

worth of photos (SenseCam). Good tools also have many properties that an

investigator does not easily learn about. Good balance between the effort required to

lean to use a device, its functionality and convenience of actual use is thus needed.

In future, it would be interesting to implement these data collection tools in

hospital setting to study the integration of the available information technologies with

the clinical work. Pictorial data (SenseCam) could help to come aware how the

technology should be designed instead of training people to adapt to poorly designed

technology. Further, clinical training could possibly benefit of the use of combination

of shadowing and SenseCam. In clinical training the interns could use the SenseCam

as a powerful tool to recall the learning situations.

8 Conclusions

To better mobilise health related information in molecular medicine requires the study

of researchers’ tasks and information access in the domain. Research into task-based

information access again requires multiple and often tedious means of data collection

for comprehensive understanding. As we pointed out, each particular method is

insufficient and incomplete, and thus triangulation between them is needed to increase

the reliability of findings. We focused on triangulating observation, logging and

SenseCam photographs. These sources yield a lot of data – the strength of the latter

two being automatic collection and the possibility of extending the date beyond what

one shadower can accomplish. However all methods are also intrusive in different

ways thereby introducing biases in the data. Shadowing may disturb, is very tedious

and challenging regarding the shadower’s knowledge but also invaluable for

understanding medical task performance (and interpreting the logs and photos). Logs

give an overview of information access, but may be incomplete and biased in various

ways. Search goals are impossible to interpret from the logs alone. SenseCam photos

and events give a valuable overview and structure for the study subject’s daily

activities. However, the current state of the art reveals no specifics on digital

information access, and human interpretation is always required based on an

understanding of the task processes. As these methods provide a large quantity of

valuable data, one needs good research questions as a life vest to avoid drowning in

them. Careful use of the methods will, however, provide a comprehensive basis for

developing information access in molecular medicine.

57

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Microsoft Research under grant 2007-056, the Irish

Research Council for Science, Engineering, and Technology; by Science Foundation

Ireland under grant 07/CE/I1147; and by the Academy of Finland under grants

#120996 and, #124131, #204978.

References

1. Byrne D, Doherty A.R., Smeaton A.F., Jones G., Kumpulainen S., and Jarvelin K. (2008).

The SenseCam as a Tool for Task Observation. HCI 2008 – 22

nd

BCS HCI Group

Conference, Liverpool, U.K., 1-5 September 2008.

2. Doherty A.R., and Smeaton A.F. (2008). Automatically Segmenting Lifelog Data into

Events. WIAMIS 2008, Klagenfurt, Austria,7-9 May, 2008.

3. Hodges, S., Williams, L., Berry, E., Izadi, S., Srinivasan, J., Butler, A., Smyth, G., Kapur,

N., and Wood K. (2006). SenseCam: A Retrospective Memory Aid, In Proceedings of the

8th International Conference on Ubicomp 2006, pages 177 – 193, September, 2006.

4. Ingwersen, P., and Järvelin, K. (2005). The Turn: Integration of Information Seeking and

Retrieval in Context. Dordrecht: Springer

5. PLogger (2008). ProxyLogger description page. Online: http:// plogger.fi/index.php?id=4&

action=switch_language –accessed 7

th

Apr, 2008.

6. Roos, A., Kumpulainen, S., Järvelin, K, and Hedlund, T. (2008). Information environment

of the researchers in Molecular Medicine. Information Research, 13(3) paper 353.

(Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/13-3/paper353.html)

7. Ruthven, I. (2008). Interactive information retrieval. In: Cronin, B. (Ed.) Annual Review of

Information Science and Technology: Volume 42 (ARIST 42). Medford, NJ: Information

Today. Pp. 43-92.

8. Vakkari, P. (2003). Task-based information searching. Annual Review of Information

Science and Technology 2003, vol. 37 (B. Cronin, Ed.) Information Today: Medford, NJ,

2002, 413-464.

58