USING CASUAL LOOP DIAGRAM TO BETTER

UNDERSTANDING OF e-BUSINESS MODELS

M. R. Gholamian, A. Hamzehei

Department of Electronic Commerce, Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST), Narmak, Tehran, Iran

gholamian@iust.ac.ir, a_hamzaii@ind.iust.ac.ir

B. Kiani

Green Research Center, Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST), Narmak, Tehran, Iran

kiyani@iust.ac.ir

S.H. Hosseini

Department of Industrial Engineering, Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST), Narmak, Tehran, Iran

hoseini@ind.iust.ac.ir

Keywords: e-Business, e-Business model, Causal loop diagram.

Abstract: Using the concept of business models can help companies understand, communicate, share, change,

measure, simulate and learn more about the different aspects of e-business in their firms. Better

understanding of e-business models helps managers and related staffs to better apply the business model.

The main objective of this paper is to use Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) as a useful tool to capture the

structure of e-business systems in order to achieve a better understanding of an e-business model. The

proposed CLD gives a helpful insight which is useful for managers to learn more about the e-business

model.

1 INTRODUCTION

We live in a competitive, rapidly changing and an

increasingly uncertain economic environment that

makes business decisions complex and difficult.

Companies are confronted with new information and

communication technologies, shorter product life

cycles, global markets and tougher competition. In

this hostile business environment firms should be

able to manage multiple distribution channels,

complicated supply chains, expensive IT

implementations, and strategic partnerships and still

stay flexible enough to react to market changes.

Astonishingly, the concepts and software tools that

help managers facilitate strategic business decisions

in this difficult environment are still scarce

(Osterwalder, 2004). Every manager and

entrepreneur does have an intuitive understanding of

the company’s business model, but even though this

business model influences all important decisions, in

many cases she or he is rarely able to communicate

it in a clear and simple way (Linder and Cantrell,

2000). How can one decide on a particular business

issue or change it, if it is not clearly understood by

the parties involved? Therefore, it would be

interesting to think of a set of tools that would allow

business people to understand what their business

model would be and of what essential elements it

could be composed of, tools that would let them

easily share this model to others and that would let

them change and play around with it in order to

learn about business opportunities (Osterwalder,

2004).

A business model is often defined as an

architecture for the product, service and information

flows, including business actors, potential benefits,

and sources of revenues, or as a method for

managing resources to provide better customer

values and make money (Afuah and Tucci, 2001;

Terano and Naitoh, 2004; Chien-Chih Yu, 2005).

Above all, a business model is a model of a

business. A model, on the other hand, is only an

artificial representation of reality. It therefore has to

detract focus from certain aspects while

concentrating on others; it is impossible for all the

variables that comprise reality to be adequately and

consistently represented, particularly if the goal is to

control for the effect of certain factors over others. A

model can be descriptive or predictive, but in many

cases people would not rely on the outcomes of the

model only, when making a decision. This is

because a model cannot (and should not) be a

complete and precise representation of reality—even

for very simple social systems. Even if it could,

people would not recognize it as such, because as

what is considered to be important for the model

depends on the position of the observer (Petrovic et

al., 2002).

Recalling all said above, the importance of an e-

business model usage in the performance of an e-

business model is brightly evident. In the other hand,

a good understanding of e-business model has a

great impact on the quality and level of its

utilization. Therefore, in this paper, we will use

Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) as a useful tool to find

out the structure of e-business systems in order to

achieve a better understanding of an e-business

model. To do so, we will use a specific e-business

model, called e-Business Model Ontology (BMO).

Following, in the paper, in the next section we

describe the BMO and its building blocks. In the

section 3, CLD will be introduced and finally we

will show how CLD can be used to give a better

understanding and explaining of e-business model

especially BMO.

2 e-BUSINESS MODEL

ONTOLOGY

Alexander Osterwalder in 2004 worked on an E-

Business model which includes almost all areas of

E-Business as his doctoral thesis. This section tries

to explain his model named E-Business Model

Ontology. This E-Business model is an ontology that

allows to accurately describing the business model

of a firm. Influenced by the Balanced Scorecard

approach (Kaplan and Norton, 1992), and more

generally business management literature (Markides,

1999) suggested adopting a framework which

emphasizes on the following four areas that a

business model has to address:

Product: What business the company is in, the

products and the value propositions offered to

the market.

Customer Interface: Who the company's target

customers are, how it delivers products and

services to them, and how it builds a strong

relationship with them.

Infrastructure Management: How and with

whom the company efficiently performs

infrastructural or logistical issues, and under

what kind of network enterprise.

Financial Aspects: What is the revenue model,

the cost structure and the business model’s

sustainability?

These four areas can be compared to the four

perspectives of Norton and Kaplan's Balanced

Scorecard approach (Kaplan and Norton, 1992). The

Balanced Scorecard is a management concept

developed in the early 90s that helps managers

measure and monitor indicators other than purely

financial ones. Norton and Kaplan identify four

perspectives of the firm on which executives must

keep an eye to conduct successful business. From

the customer perspective the company asks itself

how it is being seen by its customers. From the

Internal perspective, the company reflects on what it

must excel at. From the innovation and learning

perspective the company analyzes how it can

continue to improve and create value. Finally, from

the financial perspective a company asks itself how

it looks at shareholders. While the four areas are a

rough categorization the nine elements are the core

of the ontology. These elements, presented in Table

1, are a synthesis of the business model literature

review and consist of value proposition, target

customer, distribution channel, relationship, value

configuration, capability, partnership, cost structure

and revenue model. Figure 1 gives the reader a first

impression of the business model ontology and

depicts how the mentioned Business Model

Ontology elements are related to each other.

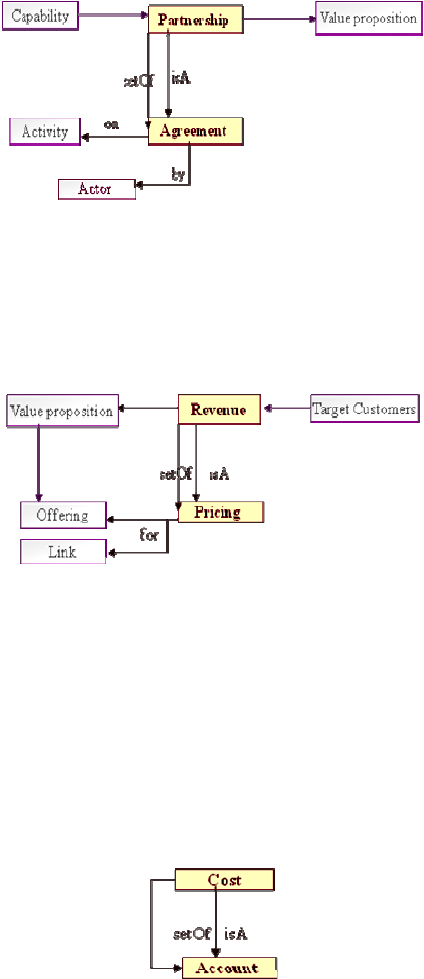

Every business model element can be

decomposed into a set of defined sub elements. As

illustrated in the graphical descriptions and defined

in the tables, element and sub-elements are related to

each other through "setof" and "isA" relationships.

Product covers all aspects of what a firm offers its

customers. This comprises not only the company's

bundles of products and services but the manner in

which it differentiates itself from its competitors.

Product is composed of the element value

proposition, which can be decomposed into its

elementary offering(s) (see Figure 2).

Table 1: The nine business model building blocks (Osterwalder, 2004).

Pillar Building Block of

Business Model

Description

Product

Value Proposition

A Value Proposition is an overall view of a company's bundle of products and services

that are of value to the customer.

Customer

Interface

Target Customer

The Target Customer is a segment of customers a company wants to offer value to.

Distribution Channel

A Distribution Channel is a means of getting in touch with the customer.

Relationship

The Relationship describes the kind of link a company establishes between itself and the

customer.

Infrastructure

Management

Value Configuration

The Value Configuration describes the arrangement of activities and resources that are

necessary to create value for the customer.

Capability

A capability is the ability to execute a repeatable pattern of actions that is necessary in

order to create value for the customer.

Partnership

A Partnership is a voluntarily initiated cooperative agreement between two or more

companies in order to create value for the customer.

Financial

Aspects

Cost Structure

The Cost Structure is the representation in money of all the means employed in the

business model.

Revenue Model

The Revenue Model describes the way a company makes money through a variety of

revenue flows.

Figure 1: The Business Model Ontology (Osterwalder, 2004).

The element value proposition is an overall view

of one of the firm's bundles of products and services

that together represent value for a specific customer

segment.

Figure 2: Product.

It describes the way a firm differentiates itself

from its competitors and is the reason why

customers buy from a certain firm and not from

another one.

The target customer is the second element of the

business model ontology (Figure 3). Selecting a

company's target customers is all about the

segmentation. Effective segmentation enables a

company to allocate investment resources to target

customers that will be most attracted by its value

proposition. The target customer definition will also

helps a firm to define through which channels it

effectively wants to reach its clients. In order to

refine a customer segmentation companies usually

decompose a target customer segment into a set of

further characteristics called criterion.

Figure 3: Target Customer.

The distribution channel is the third element of

the business model ontology (Figure 4). Distribution

channels are the connection between a firm's value

propositions and its target customers. A distribution

channel allows a company to deliver a value to its

customer directly. A distribution channel describes

how a company gets in touch with its customers. Its

purpose is to make the right quantities of the right

products or services available at the right place, at

the right time to the right people (Pitt and Berthon,

1999).

Figure 4: Distribution Channel.

The fourth element of the business model

ontology concerns the relationships a company

builds with its customers (Figure 5). All customer

interactions between a firm and its clients affect the

strength of the relationship a company builds with

its customers. But as interactions come at a given

cost, firms must carefully define what kind of

relationship they want to establish with what kind of

customer. Profits from customer relationships are the

lifeblood of all businesses. These profits can be

achieved through the acquisition of new customers,

the enhancement of profitability of existing

customers and the extension of the duration of

existing customer relationships. Companies must

analyze customer data in order to evaluate what type

of customer they want to seduce and acquire,

whether they are profitable and worth spending

retention efforts or not and whether they are likely to

be subjected to add-on selling or not (Blattberg and

Getz, 2001). Then firms must define the different

mechanisms they want to use to create and maintain

a customer relationship and leverage customer

equity.

Figure 5: Relationship.

Capability is the fifth element of the business

model ontology (Figure 6). Capabilities described as

repeatable patterns of action in the use of assets to

create, produce, and/or offer products and services to

the market. Thus, a firm has to dispose of a set of

capabilityies in order to provide its value

proposition. These capabilities depend on the assets

or resources of the firm. And, increasingly, they are

outsourced to partners, while using e-business

technologies to maintain the tight integration that is

necessary for a firm to function efficiently.

Figure 6: Capability.

The value configuration is the sixth element of

the business model ontology (Figure 7). The value

configuration of a firm describes the arrangement of

one or several activity (ies) in order to provide a

value proposition. As outlined above, the main

purpose of a company is the creation of value that

customers are willing to pay for. This value is the

outcome of a configuration of inside and outside

activities and processes. The value configuration

shows all activities necessary and the links among

them, in order to create value for the customer.

Figure 7: Value Configuration.

The seventh element of the business model

ontology is the partnership network. A partnership

is a voluntarily initiated cooperative agreement

formed between two or more independent

companies in order to carry out a project or specific

activity jointly by coordinating the necessary

capabilityies, resources and activityies. A

company’s partner network outlines which parts of

the activity configuration and which resources are

distributed among the firm’s partners.

Figure 8: Partnership.

The REVENUE MODEL is the eighth element

of the business model ontology and it measures the

ability of a firm to translate the value it offered to its

customers into money and incoming revenue

streams.

Figure 9: Revenue Model.

This element measures all the costs the firm

incurs in order to create, market and deliver value to

its customers. It sets a price tag on all the resources,

assets, activities and partner network relationships

and exchanges that cost the company money. As the

firm focuses on its core competencies and activities

and relies on partner networks for other non-core

competencies and activities there is an important

potential for cost savings in the value creation

process.

Figure 10: Cost Structure.

3 CAUSAL LOOP DIAGRAM

Yet our mental models often fail to include the

critical feedbacks determining the dynamics of our

systems. A useful way to capture the structure of

systems is causal loop diagram (CLD) (Sterman,

2000). The casual loop diagram represents the way

in which a system works. The primary purpose of

the CLD is to depict casual hypothesis, so as to

make the presentation of the structure in an

aggregate form. The CLD helps the user to quickly

communicate the feedback structure and underlying

assumptions (Sushil, 1993). CLDs are an important

tool for representing the feedback structure of

systems. Long used in academic work, and

increasingly common in business, CLDs are

excellent for (Sterman, 2000):

Quickly capturing your hypotheses about the

causes of dynamics;

Eliciting and capturing the mental models of

individuals or teams;

Communicating the important feedbacks you

believe are responsible for a problem.

A causal diagram consists of variables connected

by arrows denoting the causal influences among the

variables. The important feedback loops are also

identified in the diagram. Variables are related by

causal links, shown by arrows (Sterman, 2000). The

casual relationship depicts that one element affecting

another element. A causal loop diagram has been

used to model this causality relationship. Positive

relationship refers to ‘a condition in which a casual

element, A, results in a positive influence on B,

where the increase of A value responds to the B

value with a positive increase’ and Negative

relationship refers to ‘a condition in which a causal

element, A, results in a negative influence on B,

where the increase of A value responds to the B

value with a decrease’ (Richardson, 1986).

Link polarities describe the structure of the

system. They do not describe the behavior of the

variables. That is, they describe what would happen

IF there were a change. They do not describe what

actually happens. The causal diagram doesn’t tell

you what will happen. Rather, it tells you what

would happen if the variable were to change

(Sterman, 2000).

The important loops are highlighted by a loop

identifier which shows whether the loop is a positive

(reinforcing) or negative (balancing) feedback. The

dynamic behavior of the system can be caused by a

feedback loop, and there are two types of feedback:

reinforcing (R) and balancing (B). As shown in

figure 11, increases in population increases the

number of birth, which again increases the overall

population. It is a reinforcing loop. In the contrary,

the greater the population, the higher the number of

deaths, and then the population decrease. It is a

balancing loop. In addition, it is not easy to

understand the complexity involved with the

dynamic changes among elements and the target

system in which casual relationships and feedback

loops exist.

Population

Death Rate

Birth Rate

+

-

+

+

Figure 11: The diagram of casual relationship.

In the next section we will develop a CLD to

explain the logic and structure of the introduced e-

business model and consequently we will show how

that CLD is validated.

4 USING CLD TO BETTER

UNDERSTANDING OF BMO

In this section Casual Loop Diagram is used to give

a better understanding of introduced e-business

model which was in pervious section. The CLD is

drawn based on the BMO; it explains the logic of

model and shows the interaction of each model

building blocks; it also facilitates the understanding

of the model and consequently facilitates the

applying of it. We draw a simple CLD which only

shows the main loops and main interactions in order

to having a well-defined CLD that is consistent with

the purpose of this paper. Figure 12 shows the CLD.

There are six loops shown partially in different

colors in the figure as follows:

PROSPERITY (balancing loop; in blue)

OFFERING (reinforcing loop; partially in red)

RESOURCE SUPPLEMENT (balancing loop;

partially in green)

ACTIVITY ARRANGEMENT (balancing

loop; partially in purple)

CHANNEL ADJUSTMENT (balancing loop;

in orange)

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP CONTROL

(reinforcing loop; partially in black)

Following, we describe these loops:

The logic of the first loop, named

PROSPERITY, is as follows: As Capabilities

increase, ceteris paribus, with correct management,

the Offering of company increases. This rise in

Offering, ceteris paribus, causes a rise in the Value

which proposed to the customer; therefore, as a

result, Customer population increases due to a

higher value proposition which satisfied customers.

This increase causes an increase in Revenue.

Consequently, this rise, ceteris paribus, causes an

increase in Profit and then causes an increase in the

dedicated amount of profit for raising Resources

which closes the loop and ensures that, ceteris

paribus, over time Capabilities will be higher than it

otherwise would have been. This loop shows the

interaction of the all four blocks of the model

showed in Figure 1: INFRASTRUCTURE,

PRODUCT, CUSTOMER INTERFACE, and

FINANCIAL ASPECTS.

The logic of the second loop, named

OFFERING, is as follows: As in pervious loop

mentioned, an increase in Capabilities finally causes

a rise in Value Proposition which causes having

more Costs. This rise in costs, ceteris paribus, causes

a decrease in Profit which causes a fall in the

dedicated amount of profit for raising Resources.

This fall closes the loop and ensures that, ceteris

paribus, over time Capabilities will be lower than it

otherwise would have been. This loop shows the

interaction of the three blocks of the model showed

in Figure 1: INFRASTRUCTURE, PRODUCT, and

FINANCIAL ASPECTS.

The logic of the third loop, named

RESOURCE

SUPPLEMENT, is as follows: A fall in Capabilities

causes a rise in Partnership since the company needs

more investment to improve its Resources and

consequently its Capabilities. A rise in Partnership,

as said, causes a rise in Funding and therefore,

ceteris paribus, causes a rise in Resources. This

closes the loop and ensures that, ceteris paribus, over

time Capabilities will be higher than it otherwise

would have been. This loop shows the interaction of

one block of the model showed in Figure 1:

INFRASTRUCTURE.

The logic of the fourth loop, named ACTIVITY

ARRANGEMENT, is as follows: A fall in

Capabilities causes a rise in Partnership for the

reason that the company needs more Capabilities

and more abilities to configure these Capabilities in

order to more Offering. As Partnership rises the

Ability of company to configure the Capabilities

rises and, ceteris paribus, it causes a rise in Offering.

As said above, this finally raises Capabilities. This

loop shows the interaction of the two blocks of the

model showed in Figure 1: INFRASTRUCTURE

and PRODUCT.

The logic of the fifth loop, named CHANNEL

ADJUSTMENT, is as follows: As Customer

Identification increases, the Compatibility of

Linking Channel which company chooses to make

relationship with customers rises. This, ceteris paribus,

causes a rise in the Performance of Linking Channel.

Figure 12: The Casual Loop Diagram of e-Business Model Ontology.

This rise and the type of Mechanisms which

company uses finally raise the total Performance of

Relationship with customers. When company has a

good insight about its customers and its customer

Relationship Performance is high, the company

makes fewer efforts for Identification of its

customers because it knows the customers very

well. It is obvious that when customer Relationship

Performance rises the Customer population rises

too. This loop performs in one block of the model

showed in Figure 1: CUSTOMER INTERFACE.

There is another loop which shows the

relationship between the last loop (CHANNEL

ADJUSTMENT) and others which named as

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP CONTROL; as

Relationship Performance increases, with

sufficient and excellent Value Proposition,

Customer population rise; the increase in

Customers, with appropriate Mechanisms, causes a

rise in Relationship Performance.

The main loops, which produce the dynamic

behavior, are described above. In the section 2 the

models building blocks is introduced and the

constituted components is delineated. In this

section we tried to show the relationships and the

impacts of building blocks on each others. The

readers that have an understanding with these

relationships and impacts could have better

understanding of BMO; therefore, this will be

useful for practical purposes.

5 CONCLUSIONS

A business model is often defined as architecture

for the product, service and information flows,

including business actors, potential benefits, and

sources of revenues, or as a method for managing

resources to provide better customer values and

making money. The importance of an e-business

model usage in the performance of an e-business

model is brightly evident. In the other hand, a good

understanding of e-business model has a great

impact on the quality and level of its utilization.

Therefore, in this paper, we used CLD as a useful

tool to capture the structure of e-business systems

in order to achieving a better understanding of an

e-business model. To do so, we used a specific e-

business model, called e-Business Model Ontology

(BMO) and described its building blocks. In the

section 3, CLD is introduced and finally we

showed how CLD can be used to give a better

understanding and explaining of e-business

models, especially BMO. Further research could

be drawing of the Stock Flow Diagram (SFD)

which can be used for sensitivity analysis, scenario

building, and policy analysis for practical

purposes. The limitation of this research is

investigating this approach in a case study in order

to find a practical usage of this research.

REFERENCES

Afuah, A., Tucci, C. L., 2001. Internet Business Models

and Strategies: Text and Cases. McGraw-Hill.

Terano, T., Naitoh, K., 2004, Agent-Based Modeling for

Competing Firms: From Balanced Scorecards to

Multi-Objective Strategies. Proceedings of the 37th

Hawaii International Conference on Systems

Sciences, 8p.

Chien-Chih Yu, 2005. Linking the Balanced Scorecard

to Business Models for Value-Based Strategic

Management in e-Business. EC-Web 2005, LNCS

3590, pp. 158 – 167.

Osterwalder A., 2004. The Business Model Ontology - a

proposition in a design science approach. thesis,

University of Lausanne.

Linder, J., S. Cantrell, 2000. Changing Business Models:

Surveying the Landscape, accenture Institute for

Strategic Change.

Petrovic, O., Kittl, C., Teksten, R. D., 2002. Developing

Business Models for eBusiness. evolaris eBusiness

Competence Center.

Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P., 1992. The balanced

scorecard--measures that drive performance.

Harvard Business Review 70(1).

Markides, C., 1999. All the Right Moves. Boston,

Harvard Business School Press.

Pitt, L., Berthon, P., 1999. Changing Channels: The

Impact of the Internet on Distribution Strategy.

Business Horizons.

Blattberg, R., Getz, G., 2001. Customer Equity. Boston,

Harvard Business School Press.

Sterman, J. D., 2000. Busyness Dynamics – systems

thinking and modeling for a complex world, John

Wiley.

Sushil, 1993. System Dynamics- A Practical Approach

for Managerial Problems, John Wiley.

Richardson, G., 1986. Problems with causal-loop

diagrams. System Dynamics Review, Vol. 2, No. 2,

pp. 158–170.