LEARNING SUPPORT FOR ENGLISH COMPOSITION

BY ASKING BACK QUESTIONS

Hiroki Hidaka, Yasuhiko Watanabe and Yoshihiro Okada

Department of Media Informatics, Ryukoku University, Otsu, Shiga, Japan

Keywords:

Learning support for English composition, Asking back question, Realizable possibility, Suppositive expres-

sions.

Abstract:

There are several gaps between Japanese and English expressions, such as suppositive expressions. These gaps

make it difficult for Japanese students to study English composition. For example, realizable possibilities are

described clearly in English suppositive expressions, on the other hand, they are frequently omitted in Japanese

suppositive expressions. As a result, when Japanese students translate Japanese suppositive expressions into

English, they are often forced to reveal the realizable possibilities which are not described clearly in Japanese

expressions. In this way, it is important to make students aware of realizable possibilities when they try to

translate Japanese suppositive expressions into English. To solve this problem, in this paper, we propose a

learning support method for English composition by using asking back questions. Our system asks users back

and makes them aware of realizable possibility.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is difficult for Japanese students to study English

composition because there are several gaps between

Japanese and English expressions. Take realizable

possibility in suppositive expressions for example. In

English sentences, realizable possibilities are clearly

expressed in suppositive expressions.

(ex 1) I’ll call you when I get to Narita Airport.

(ex 2) If I get to Narita Airport, I’ll call you.

(ex 1) shows that the speaker is sure to get to Narita

Airport. On the other hand, (ex 2) shows that the

speaker has a fifty-fifty chance of getting there. In

contrast, in Japanese sentences, realizable possibili-

ties are frequently omitted or expressed ambiguously.

(ex 3) Narita kuko (airport) ni (to) tsui (get) tara

(when/if) denwa (call) shimasu (will).

In this sentence, the possibility of getting to Narita

Airport is not expressed clearly. Both a man who is

sure to get to Narita Airport and a man who has a

fifty-fifty chance of getting there can speak (ex 3).

As a result, when Japanese students translate

Japanese suppositive expressions into English, they

are often forced to reveal realizable possibility be-

cause they are not described clearly in Japanese sup-

positive expressions (Figure 1).

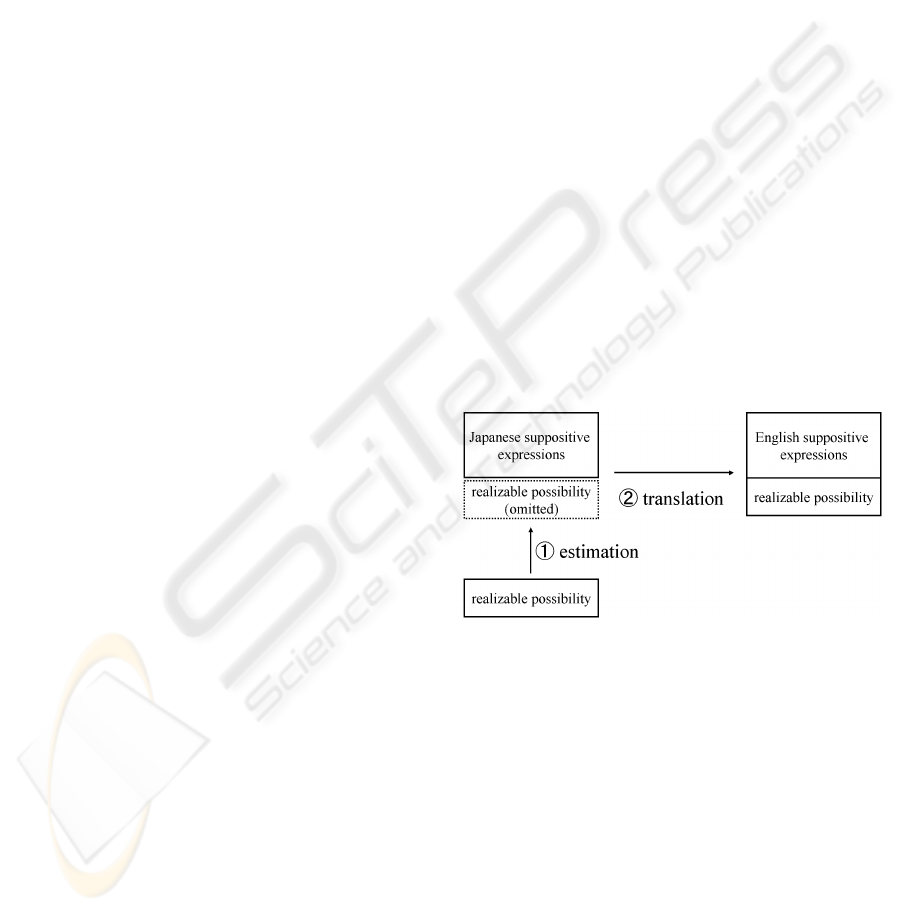

Figure 1: The translation process of Japanese suppositive

expressions into English: 1. the estimation of realizable

possibility, 2. translation.

A considerable number of studies have been made

on English composition support by extracting En-

glish expressions from Web documents (Oshika 05)

(Takeda 94) (Yamamoto 99) (EDP 07). In these stud-

ies, however, little attention has been given to the gaps

between Japanese and English expressions. Suppose

that a Japanese student wants to translate (ex 3), how-

ever, does not know that the realizable possibility is

the key to translating Japanese suppositive expres-

sions into English. If (ex 1) and (ex 2) are given as

the translation examples of (ex 3) to the student, it is

difficult for the student to determine which sentence

is proper without the viewpoint of realizable possibil-

367

Hidaka H., Watanabe Y. and Okada Y. (2009).

LEARNING SUPPORT FOR ENGLISH COMPOSITION BY ASKING BACK QUESTIONS.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 367-370

DOI: 10.5220/0001845103670370

Copyright

c

SciTePress

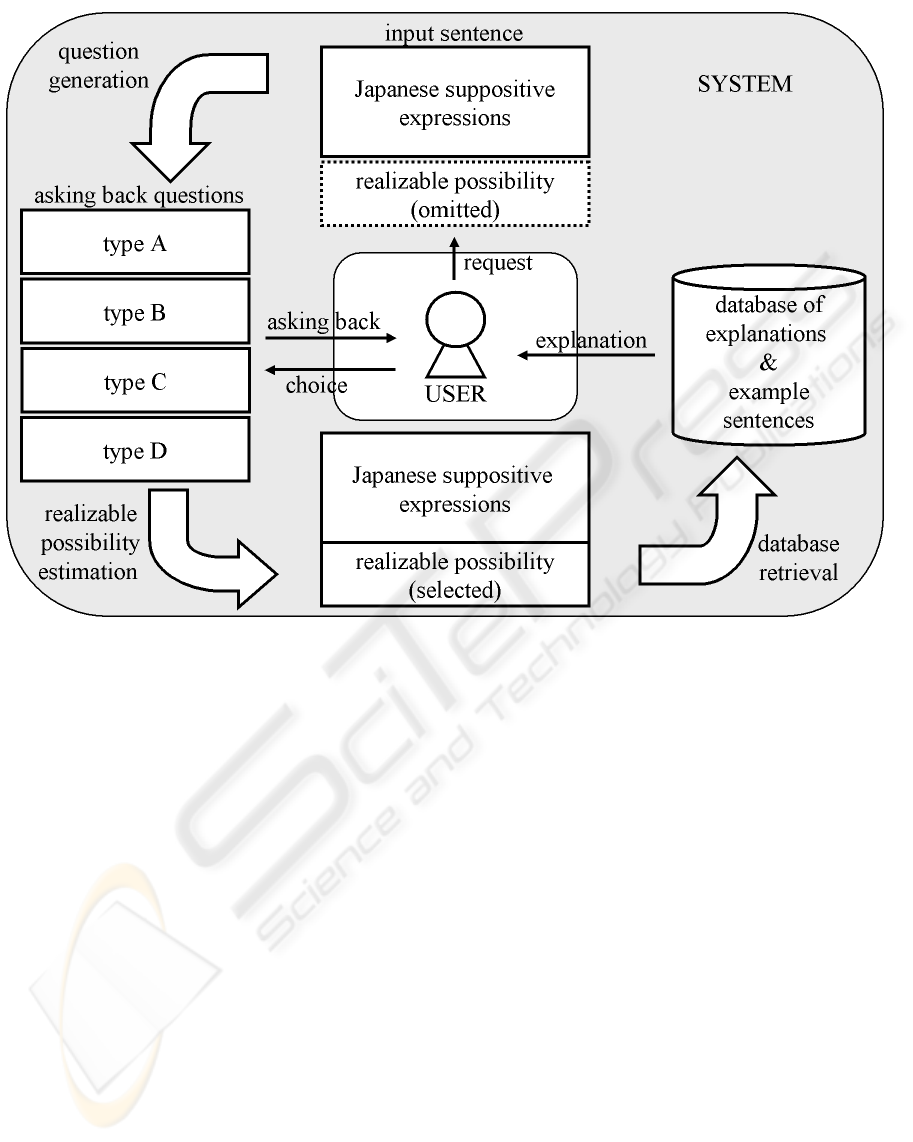

Figure 2: System overview.

ity. As a result, it is important to make students aware

of the gaps, in this case, the realizable possibility.

To solve this problem, we propose a learning sup-

port method for English composition by asking back

questions. Our system asks users back and make them

aware of the gaps between Japanese and English ex-

pressions. There are several kinds of gaps between

Japanese and English expressions. However, in this

paper, we have concentrated on suppositive expres-

sions because space is limited.

2 ASKING BACK QUESTIONS

ABOUT POSSIBILITY

From the viewpoint of realizable possibility, English

suppositive expressions can be classified into four

types:

Type A expressions about general or habitual activi-

ties and the possibility is very strong

(ex 4) When you mix red and yellow, you get or-

ange.

(ex 5) You always play baseball whenever the

weather is nice.

Type B expressions about one-time activities and the

possibility is very strong

(ex 6) You will play baseball when the weather is

nice.

Type C expressions about one-time activities and the

possibility is fifty-fifty

(ex 7) If the weather is nice, you will play base-

ball.

Type D expressions about one-time activities and the

possibility is very weak

(ex 8) If the weather was nice, you would play

baseball.

Because, in Japanese suppositive expressions, realiz-

able possibilities are frequently omitted or expressed

ambiguously, it is important to make Japanese stu-

dents aware of the realizable possibilities.

To solve this problem, our system asks users back

and make them aware of the gaps between Japanese

and English expressions. Figure 2 shows the overview

of our system. Our system applies morphologic anal-

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

368

ysis(Kurohashi 05) to an input sentence, obtains con-

ditional clause (basic and original form) and conse-

quence clause, generates four types of asking back

questions according to the rules in Figure 3 and gives

them to the user. Take (ex 9) for example.

(ex 9) moshi (when/if) tenki (weather) ga haretara

(nice), yakyu (baseball) ga dekiru (will play).

From (ex 9), our system extracts “moshi (when/if)

tenki (weather) ga haretara (nice), ” as the condi-

tional clause, on the other hand, “yakyu (baseball) ga

dekiru (will play)” as the conclusion clause. Then, ac-

cording to the rules in Figure 3, our system generates

four types of asking back questions:

Asking back question (type A) [for general or ha-

bitual activities]

(ex 10) tenki ga hareru toki ha, itsumo yakyu ga

dekiru, desu ka? (You think it always happens

that you play baseball whenever the weather is

nice, don’t you?)

Asking back question (type B) [for very strong

possibility]

(ex 11) tenki ga hareru koto ha kakujitsu ni okoru

node, moshi tenki ga harereba yakyu ga dekiru,

desu ka? (You think it is certainly that the

weather will be nice and it certainly happens that

you will play baseball, don’t you?)

Asking back question (type C) [for fifty-fifty possi-

bility]

(ex 12) tenki ga hareru ka douka wakaranai ga,

moshi tenki ga harereba yakyu ga dekiru, desu

ka? (You think it is fifty-fifty that the weather

will be nice and are tentatively planning that you

will play baseball, don’t you?)

Asking back question (type D) [for very weak pos-

sibility]

(ex 13) tenki ga hareru koto ha arie nai ga,

moshi tenki ga harereba yakyu ga dekiru, desu

ka? (You think it is almost impossible that the

weather will be nice, however, you are dreaming

that you would play baseball, don’t you?)

Then, the user answers the asking back questions,

finds a gap between Japanese and English expres-

sions, and translates the Japanese expression into En-

glish by using explanations and example sentences

which are generated by our system and consistent

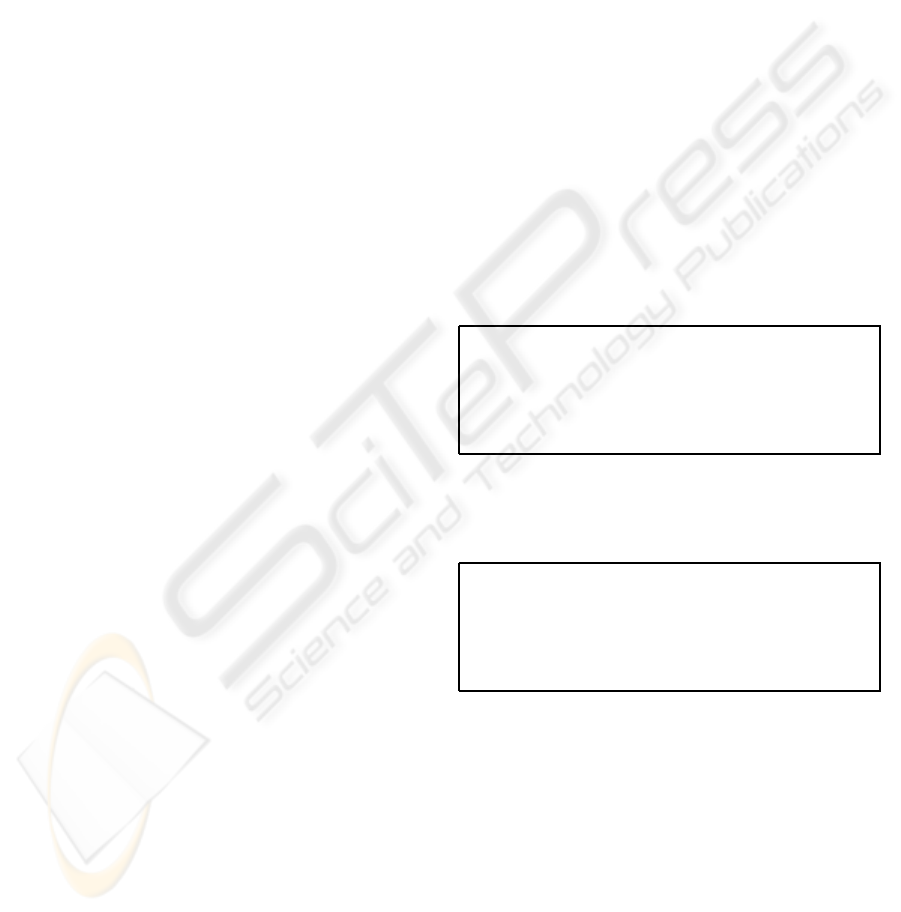

with the selected possibility. For example, Figure

4 (a) shows the explanation and example sentences

which our system gives to the user when he/she

chooses very strong realizable possibility. On the

(rule for type A) [for general or habitual activities]

[conditional clause (basic form)] toki (whenever) ha it-

sumo (always) [consequence clause] desu ka ? (You think

it always happens that [consequence clause] whenever

[condition clause], don’t you?)

(rule for type B) [for very strong possibility]

[conditional clause (basic form)] koto ha kakujitsu ni

(certainly) okoru (happen) node [conditional clause (orig-

inal form)] [consequence clause] desu ka ? (You think it is

certainly that [conditional clause] and it certainly happens

that [consequence clause], don’t you?)

(rule for type C) [for fifty-fifty possibility]

[conditional clause (basic form)] ka douka wakaranai

ga (fifty-fifty) [conditional clause (original form)] [con-

sequence clause] desu ka ? (You think it is fifty-fifty that

[conditional clause] and are tentatively planning that [con-

sequence clause], don’t you?)

(rule for type D) [for very weak possibility]

[conditional clause (basic form)] koto ha arie nai ga,

(impossible) [conditional clause (original form)] [conse-

quence clause] desu ka ? (You think it is almost impos-

sible that [conditional clause], however, you are dreaming

that [consequence clause], don’t you? )

Figure 3: Generation rules of Asking back question about

realizable possibility.

Explanation You want to compose English sup-

positive expressions with very strong realizable

possibilities. In such a case, you should not use

if clause.

Japanese Narita kuko ni tsui tara denwa shimasu

English I’ll call you when I get to Narita Airport.

(a) An explanation and example sentences for English

suppositive expressions with very strong realizable

possibilities.

Explanation You want to compose English sup-

positive expressions with fifty-fifty realizable

possibilities. In such a case, you should use if

clause.

Japanese Narita kuko ni tsui tara denwa shimasu

English If I get to Narita Airport, I’ll call you.

(b) An explanation and example sentences for English

suppositive expressions with fifty-fifty realizable

possibilities.

Figure 4: Explanations and example sentences which are

consistent with user’s selected realizable possibility.

other hand, Figure 4 (b) shows the explanation and

example sentences which our system gives to the user

when he/she chooses fifty-fifty realizable possibility.

LEARNING SUPPORT FOR ENGLISH COMPOSITION BY ASKING BACK QUESTIONS

369

3 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

We examined whether nine Japanese students under-

stood realizable possibility which was consistent with

the given situation. In this experiments, we gave the

following Japanese suppositive sentences

(input 1) 962 do (degrees centigrade) made (to)

kanetsushi (heat) tara (when/if), gin (silver) ha

tokeru (melt)

(input 2) shigoto (job) ga owat (over) tara (when/if),

renraku shimasu (get in touch)

(input 3) ano ki (the tree) wo kiritaoshi (cut down)

tara (when/if), motto (more) nagame (view) ga yoku

naru darou (be good).

and some situations of each input sentence (Figure 5)

to the students. Then, our system gave asking back

questions to the students and we examined whether

the students understood realizable possibility which

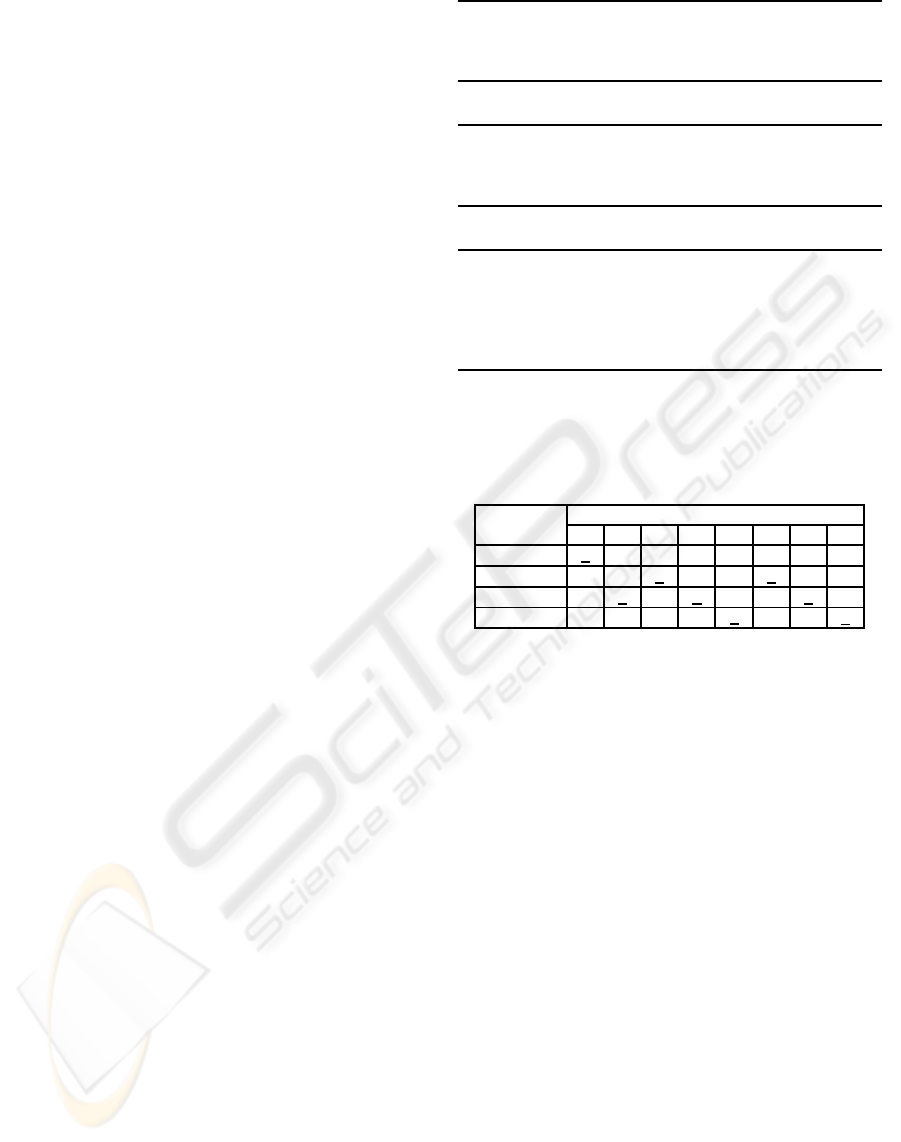

was consistent with the given situations. Table 1

shows the experimental results. In Table 1, underlined

numbers show the numbers of students who select

asking back questions which, we first thought, were

consistent with the given situations. As shown in Ta-

ble 1, students’ answers were almost the same as our

answers, except in situation 1-2 and 3-3.

In situation 1-2, we first thought that type C ask-

ing back question was consistent with situation 1-2.

However, four students selected type D asking back

question because they thought that their friends were

not specialists and it is impossible to heat silver above

900 degrees Celsius. On the other hand, in situation 3-

3, five students selected type D asking back question

which, we first thought, were consistent with situation

3-3. The reason why these five students thought the

possibility was very weak was that they thought they

could not cut down the tree in someone else’s garden.

In contrast, three students selected type C asking back

question. The reason why these three students thought

the possibility was fifty-fifty was that they thought the

tree would fall down naturally or somebody would cut

it down. In both cases, students’ answers were di-

vided and some students found the possibility which

was not consistent with what we expected, however,

consistent with what they thought. It shows the effec-

tiveness of our method.

situation 1-1 You are a science teacher. You will

tell the nature of silver to your students.

situation 1-2 You will give some advices to your friend

who intends to performing experiments.

(a) situations for input 1

situation 2-1 There are prospects of finishing your task.

situation 2-2 There are little prospects of finishing

your task.

situation 2-3 There are no prospects of finishing your task.

(b) situations for input 2

situation 3-1 You are rebuilding your house and have

already decided to cut down the tree.

situation 3-2 You are rebuilding your house and now

discussing whether you cut down the tree.

situation 3-3 You are taking a walk and watch the tree

in someone else’s garden.

(c) situations for input 3

Figure 5: Situations for input 1, 2, and 3.

Table 1: Experimental Results.

asking back situation

question 1-1 1-2 2-1 2-2 2-3 3-1 3-2 3-3

type A 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 1

type B 2 0 8 1 0 9 0 0

type C 1 5 0 8 2 0 8 3

type D 0 4 0 0 7 0 0 5

REFERENCES

Oshika, Satou, Ando, and Yamana: An English Com-

position Support System using Google, IEICE

DEWS2005, 2005 (in Japanese).

Takeda and Furugori: A Sample-Based System for Help-

ing Japanese Write English Sentences, Trans. of IPSJ,

Vol.35, No.1, 1994 (in Japanese).

Yamamoto and Kitamura: Courpus based natural language

processing and an education system using it, Trans. of

JSISE, Vol.16 No.1, 1999 (in Japanese).

Electronic Dictionary Project: EIJIRO 3rd Edition, ALC,

2007 (in Japanese).

Kurohashi and Kawahara: JUMAN Manual version 5.1,

Kyoto University, 2005 (in Japanese).

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

370