AULAWEB, WEB-BASED LEARNING AS A COMMODITY

The experience of the University of Genova

Marina Ribaudo and Marina Rui

Computer Science Department, Chemistry Department

University of Genova, Italy

Keywords:

Blended learning, Moodle, Open Source, Instructional Design, Web 2.0.

Abstract:

Starting from the academic year 2005/2006, the University of Genova has foster the use of AulaWeb, a virtual

environment based on the open source software Moodle, to promote the introduction of web-based technolo-

gies in the traditional educational process. We describe the experience of the past four years presenting the

approach we have followed to encourage the use of AulaWeb among faculties, the numbers of users we have

reached, an Instructional Design course we have organised to promote educational technology.

1 INTRODUCTION

“Networked collaborative learning is a social

oriented e-learning strategy in which collab-

oration plays the major role. Promoting the

social dimension of e-learning means consid-

ering the network not only as a mere tool for

content distribution but rather as a facilitator

for the interaction among all the participants

involved in the educational process.”

This statement, taken from (Trentin, 2008), highlights

that e-learning strategies have radically changed in the

last years, considering collaboration as a central point

of the overall learning process. Although we com-

pletely agree with this idea, we think that a lot of work

still has to be done to implement networked collabo-

rative learning in practice.

This paper describes the experience at the Univer-

sity of Genova, where a web-based portal is offered to

the academic staff and the students to support the edu-

cational process. AulaWeb

1

is the name of the portal;

it is based on the popular open source software Moo-

dle (Cole and Foster, 2007) and started its activity in

the academic year 2005/2006.

Since the early stages of its development,

AulaWeb has been thought following a user-centered

approach (Norman, 1998). Users – students, facul-

ties, staff – have been taken into account in the design

phase of the project, by introducing different user pro-

files. For each profile different communication strate-

gies have been identified to stimulate users’ partici-

1

http://www.aulaweb.unige.it/

pation and to make them feeling as a part of a larger

community collaborating in the realisation of such a

web-based learning experience.

Despite media insist we live nowadays in the

“Web 2.0 era” (O’Reilly, 2005), in our experience this

is true only in part. When dealing with large num-

bers of etherogenous users like ours, coming from dif-

ferent backgrounds, the situations is indeed different.

We have in fact encountered (and we still encounter)

some resistance when promoting the introduction of

web-based technologies in the educational process as

we will discuss in one of the next section.

Although only a small part of our users is aware

of Web 2.0 techonologies such as social-networking

sites, video sharing sites, wikis, blogs, . . . we claim

that the approach we have followed to create the user

community around AulaWeb is somehow in the spirit

of Web 2.0. The concept of “Web-as-participation-

platform” has been applied at least in the strategy

we adopted for attracting participants which has been

based exclusively on voluntary adhesion. Public

“calls for volunteers” have been launched to propose

meetings with faculties, to offer technical courses on

the use of the software and, more recently, to pro-

mote an Instructional Design (Trentin, 2007; Dick

and Carey, 1996) course to educate the educators. The

“word of mouth” and the the “push from the bottom”

– i.e. students asking for more online courses – have

done the rest thus promoting the increase and the ac-

ceptance of AulaWeb.

The balance of this paper is as follows. Sec-

tion 2 briefly introduces AulaWeb showing some of

the numbers we have reached. Section 3 describes the

41

Ribaudo M. and Rui M. (2009).

AULAWEB, WEB-BASED LEARNING AS A COMMODITY - The experience of the University of Genova.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 41-46

DOI: 10.5220/0001955900410046

Copyright

c

SciTePress

different types of users we deal with and discusses

some of the support we can provide them. Section 4

presents a project-based formative model on Instruc-

tional Design methodologies we have offered to a

sample of fifty teachers. Finally, Section 5 provoca-

tively concludes this work, motivating the title of the

paper, discussing some of the difficulties we have en-

countered and some open problems.

2 THE SERVICE AULAWEB

The University of Genova is a medium-size tradi-

tional university offering face-to-face courses. How-

ever, in the late nineties individual e-learning and

blended learning experiences have been carried out,

generally involving two types of users:

1. Early adopters, i.e. mainly experts in educational

processes, teachers and students interested into

new educational models also for their research ac-

tivities.

2. Technology addicted, i.e. mainly faculties and stu-

dents in computer science or engineering fields,

who are interested in building software platforms

and rarely suffer from the well known digital di-

vide problem.

Although the University of Genova, in its policy, still

does not consider the investments on e-learning as a

priority, starting from the beginning of 2005, an offi-

cial Committee has been formed to introduce faculty

members to the potential of the use of ICT in the edu-

cational process. At that time, a crucial task was con-

sidered the selection of a Learning Managmente Sys-

tem to be offered as a centralised service at the univer-

sity level. After taking into account both proprietary

and open source softwares, the Committee selected

Moodle (Cole and Foster, 2007), an open source solu-

tion. The reasons for this choice were manifold, some

of them are listed below:

• Financial. We decided to invest (the small amount

of) financial resources on the service, not on the

cost of software licences, and therefore we opted

for an open source solution

2

.

• Functionalities. Moodle provides a rich array of

tools to support online teaching and learning.

• Size of the Community. Among the available soft-

wares, Moodle seemed the best candidate since it

had (and still has) the widest community of users

and the more active community of developers.

2

Moodle is free software under the terms of the GNU

General Public License.

• Skills. Moodle is based on the Linux / Apache

/ MySQL / PHP suite, a technology already well

known among some members of the Committee.

As a consequence, after a few man-months, the

first prototype was ready and launched as a cen-

tralised service for the whole university.

2.1 The Architecture of Aulaweb

AulaWeb is organised into many different Moodle in-

stances, one for each program degree participating to

the project.

Technically, each instance runs on a separate vir-

tual host and authentication is obtained using the

LDAP

3

university service. Students, faculties, and

staff can access to AulaWeb using the same creden-

tials they already use for other central services the

university provides (e.g. e-mail, library catalogue, in-

tranet functions).

All the eleven Faculties of the university are

present on the portal, although with different numbers

of online courses and active users.

The only constraint we put for opening a new in-

stance was that of having a “contact person” officially

designated as the responsible for it. She is the person

that acts as the administrator of the instance and she

is also the intermediary between the technical staff of

AulaWeb and the users of the instance. When pos-

sible, she also acts as a first help to solve (simple)

technical problems posed by “her” users. The deci-

sion of requiring a responsibile for each new instance

was the only possibility for the Committe to manage

the etherogenity of the users (coming from very dif-

ferent fields, each one with its own peculiarities) and

the large population we have reached with a numeri-

cally limited technical staff.

Nowadays (February 2009) AulaWeb hosts 119

sites of program degrees, for 2242 different subjects,

with 1058 teachers, considering faculties and also

some administrative/technical staff and some external

teachers. 27641 students are enrolled and we expe-

rience more than 3000 unique users connecting ev-

ery day during the week, becoming around 2000 at

the weekend

4

. Since the University of Genova counts

41000 students, these numbers say that slightly less

than 2/3 of the students are currently registered.

It is worth noticing that the adhesion to the project

has been exclusively on voluntary base, in a pure

bottom-up approach: no one has been forced to open

3

http://www.sun.com/software/products/directory srvr ee/dir

srvr/index.xml

4

According to Moodle online statistics AulaWeb

is in the group of the largest Moodle installations

(http://moodle.org/stats/).

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

42

her subject online, the ultimate decision has always

been left to teachers. In this sense we claim we have

followed Web 2.0 suggestions by promoting the idea

of “(Aula)Web-as-participation-platform.”

It must be recognised, however, that the univer-

sity, for the simple fact of identifying AulaWeb as the

centralised platform in support to teaching activities,

has strongly facilitated the growth of the service.

3 OUR USERS

Following a user-centered approach we have identi-

fied from the early stages of the design four different

users’ profiles: students, teachers, the responsible of

each Moodle instance (also called the referent), and

the technical staff. For each profile, different activi-

ties have been carried out.

Technical staff. Responsible of the overall software

system, the technical staff keeps the contacts with the

Moodle developers community.

The technical staff periodically organises specific

Moodle technical seminars for faculty members and

for referents. The technical staff, together with the

Committee, form the (small) group of persons offer-

ing the service.

Referent. “Customer” of the service, each referent is

responsible of a Moodle instance. She can contact

the technical staff for any problem and she is also the

intermediary between the staff and the users of the

program degree she represents.

Teacher. “Customer” of the service, the teacher indi-

vidually decides if she is willing to couple her tradi-

tional lectures with online support. She can contact

the referent or the staff in case of need.

More recently, a methodological course on the use

of ICT technologies for university teachers has been

launched, as we will discuss in Section 4.

Student. The major “customer” of the service, the stu-

dent can access his Moodle instance using the uni-

versity credential and he can also call the HekpDesk

service to solve first access problems. Students can

contact their teachers and the referent for any ques-

tions concerning Moodle and especially for questions

concerning educational problems the technical staff

cannot solve. At the beginning of the project, basic

courses on the use of Moodle have been offered to

groups of students from each Faculty.

In June 2006 and July 2007 anonymous question-

naires have been distributed (via AulaWeb) to have

some feedbacks. Some results will be briefly dis-

cussed in Section 3.1.

The reader will note that an important role of e-

learning, the online tutor, is missing in our organisa-

tion. Indeed, the service cannot offer online tutoring

to academic staff and students. The choice of having

online tutors is demanded to the internal organisation

of each course degree and not to the central staff that

can provide technical support “only”. Of course, in

case of large numbers like ours, this is anyhow a hard

task.

3.1 Students’ Feedbacks

Anonymous questionnaires have been distributed to

all the students enrolled in AulaWeb proposing gen-

eral questions such as (a) “How far do you live from

the University?”, and other questions related to the

use of Moodle, for example (b) “Which is your preva-

lent activity on AulaWeb?”, (c) “How was your in-

teraction with the teacher/tutor/etc. through Moodle

tools?” We also asked for general comments and sug-

gestions.

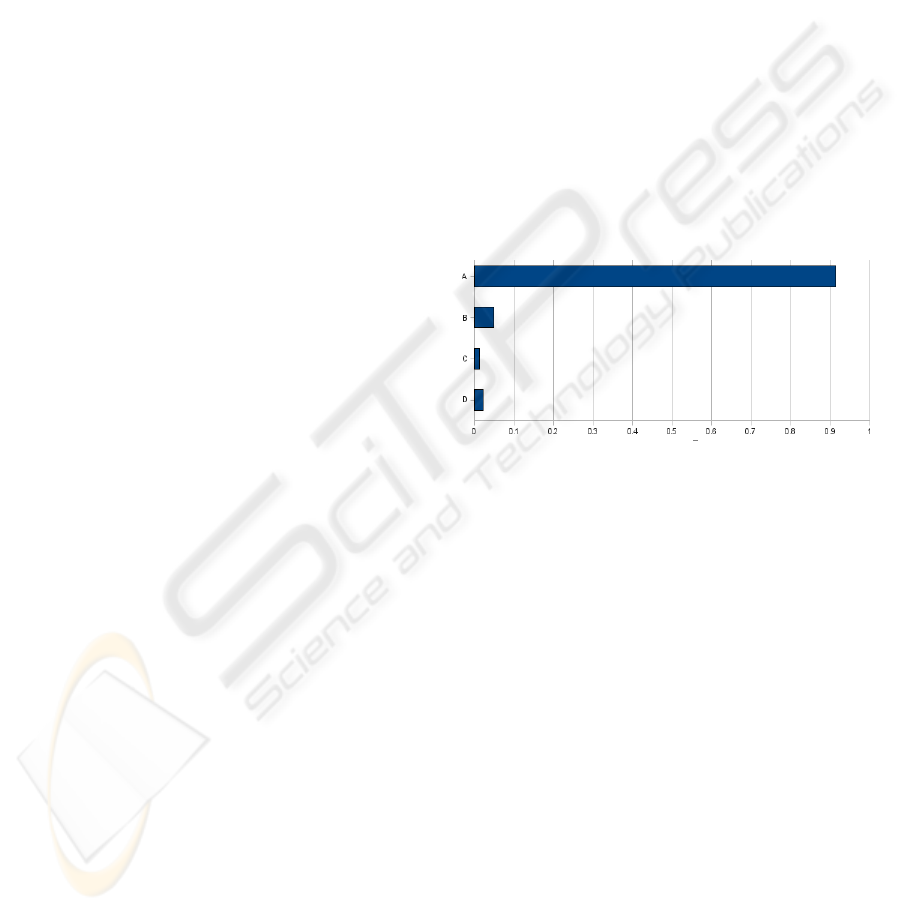

A: Download of material B: Online assignments

C: Ask questions via forums D: Other

Figure 1: Prevalent activity on AulaWeb.

Figure 1 shows the answers to question (b). As it can

be observed, the download of material (slides, papers,

lecture notes) is the prevalent activity (91.5%), fol-

lowed by the online assignment activity (5%). This

was not unexpected since we are a traditional univer-

sity trying to promote web-based technologies in the

educational process, until now mostly based on lec-

turing and information giving.

Figure 2 shows the answers to question (c). Only

38.78% of the students said that online interaction

was frequent and without any problem, while the

other cases show that the interaction was scarce

(24.05%) or nonexistent (26.17%) thus pointing out

a lack of online communication for half of the inter-

viewed.

Particularly interesting have been some comments

we received. Among them, we recall the suggestion

of unifying AulaWeb with the various web sites of the

different program degrees and departments in order to

facilitate the retrieval of all the didactic information,

the request of learning material open and accessible

to everyone, the request of video lessons for those

AULAWEB, WEB-BASED LEARNING AS A COMMODITY - The experience of the University of Genova

43

A: Nonexistent B: Scarce

C: Technical problems D: Frequent but with problems

E: Frequent without any problem

Figure 2: Quality of the interaction on AulaWeb.

students that cannot attend in-presence classes. We

end this brief discussion of the results with one of the

provocative comments we received: “Please tell our

teachers that Internet is not the future, Internet is to-

day!”

(Yueh and Hsu, 2008) presents the results of a

questionnaire distributed to the “other side of the

users”, the professors, obtaining similar results. They

observe that “one of the barriers limiting LMS use at

the universities is the fear of technology.” Thanks to

the introduction of a team of instructional specialists

supporting faculty members, “many professors indi-

cated their instructional strategies and teaching styles

had changed.” This will be the subject of next section.

4 WEB ENHANCED LEARNING

The number of users enrolled to AulaWeb has been

encouraging, thus showing the interest of our commu-

nity in the use of educational technology to improve

the teaching/learning process. However, in the first

years of activity, most of the work has been mainly

technical, being related to the setting up of Moodle

intances and to the training on the use of the differ-

ent features offered by the Moodle platform. Fortu-

nately, a part of the European Social Fund 2007/2008

has been invested into a new project, whose aim was

that of increasing the offer of courses with online sup-

port, not only from a numerical point of view but also

from a “qualitative” point of view.

Following the usual approach already experienced

in the past, we launched a new public “call for vol-

unteers” willing to become students of an Instruc-

tional Design course and to acquire new skills in

the methodological aspects of online education, thus

starting to fill a gap we were aware of. Univer-

sity teachers in fact rarely come into contact with

Instructional Design. Up to now each one refines

a personal style in the design and the management

of the teaching/learning process mainly based on in-

presence lessons. However, such spontaneousness

could work in classroom teaching but is not advis-

able in technology enhanced learning which depends

on instructional design no matter which is the chosen

learning approach – content driven learning, collabo-

rative learning, blended learning.

Of course this does not mean that teachers should

become instructional designers – they should play the

main role of subject matter experts and educators.

Nevertheless, the more they are involved in the de-

sign, development and management of online activ-

ities the higher the quality of the teaching/learning

process will be.

Having in mind the previous considerations, the

action called Web Enhanced Learning (WEL) has

been launched, with the specific objectives of devis-

ing and experimenting a model for the transfer of in-

structional design knowledge and skills to subject-

oriented university teachers.

4.1 Organisation of Wel

The WEL course

5

, delivered by ITD (the Institute for

Didactic Technologies of CNR) experts, has been or-

ganised into three distinct moments.

1. In the first phase (May 2008) two plenary lec-

tures have been organised to present university

teachers (1) an overview on the use of ICT tech-

nologies for educational methods at the university

level and (2) the Instructional Design methodol-

ogy (Trentin, 2001) they were going to follow to

redesign their teaching strategies.

At the end of the second plenary lecture all those

teachers willing to continue the project have been

asked to committ themselves to actively partici-

pate in the next phases.

2. In the second phase (May-June 2008) two in-

dividual face-to-face meetings with CNR co-

designers have been organised. Each participant

has been asked to think her course in terms of

macro-design (i.e. goals and objectives defini-

tion, evaluation criteria, types of activities, first

version of the course guide) and micro-design

(i.e. providing a detailed storyboard of the course

with a description of the organisation of the mod-

ules, planned activities, initial messages for the

virtual class, activities scheduling). In parallel, on

demand technical courses have also been organ-

ised for small groups of participants. Several soft-

wares have been presented, including softwares

for content production, graphic and video editors.

Moodle modules have been introduced as well.

5

http://elearning.aulaweb.unige.it/

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

44

3. The third and last phase started in September 2008

with the last face-to-face meeting with CNR co-

designers: A sort of auditing to check the work

done. The third step ended with the launch of

first semester courses, revisited.

A final plenary meeting has been scheduled for

February 2009, before the beginning of the second

semester, to discuss the experiences of those col-

leagues who have been online with first semester sub-

jects.

4.2 Users’ Participation

Around 100 employees of the university (faculties and

staff) attended the two plenary sessions and, among

them, 46 accepted – on a voluntary base – to ac-

tively continue the project for a total of 30 differ-

ent projects (14 for the first semester). There is a

high variety of subjects, since disciplines in umanis-

tic and scientific fields have been proposed. The ma-

jority of the projects (still) use a blended approach

(online/onsite), 13 will add collaborative strategies to

traditional teaching, 12 will use AulaWeb for content

driven learning, 5 will use both strategies.

This project is still underway and therefore de-

tailed results will be available only at the end of this

academic year. However, we have collected some pre-

liminary feedbacks from the educators that witness

their level of satisfaction. Due to the lack of space we

mention only two of the responses we had. The sec-

ond, in particular, highlights that WEL has been the

occasion to rethink the traditional teaching as well.

1. “I admit I have attended the WEL course with

enthusiasm, trying to do my best to develop an

innovative didactic module to be offered entirely

online in the Faculty of Pharmacy in the second

semester. I know several students have already

chosen the module, including some students com-

ing from another Faculty and two students that

will spend the whole year abroad with the Eras-

mus mobility project. This gives me a strong sense

of gratification and further stimulates my engag-

ment in this experimentation.”

2. “The model proposed during WEL pointed out

that I was wrong in my na

¨

ıve teaching approach. I

have always been working starting from the obvi-

ous/natural/interesting topics and then trying to

compact them to fit in the time schedule of the

course. Now I have understood that I should

start from the competences students should ac-

quire during the course and then making the right

plan to guarantee the final result.Posed in this

terms, the design of a course seems very similar

to the development of a software system (or to any

other type of system, I suppose) since we can iden-

tify several steps:

(a) Requirements analysis (also in WEL)

(b) Design (micro and macro-design in WEL)

(c) Coding (content production in WEL)

(d) Testing (students’ evaluation

6

)

(e) Delivery (the course passes to teachers)

(f) Operation (the course in online)”

One of the author of this paper is currently online

with an advanced course offered in last year of the

Computer Science curriculum. The course mixes in-

presence lectures with online activities. Students,

split into small groups, are asked to collaboratively

write a cookbook of software examples using a wiki.

All the decisions are taken by sending posts to a

technical forum associated with the wiki or by com-

municating via Skype. This example constitutes a

privileged point of view: the course is on Network

Technologies, it has only 13 participants, students

and theachers are expert in the use of software tools.

Moreover, the subject is somehow auto-referential:

teaching network technologies with the help of net-

work technologies seems straightforward. We think

these are crucial points for the success of the virtual

class as we will discuss in the next section.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have presented the project AulaWeb, discussing

its evolution during the last four years. Many impor-

tant details have been necessarily omitted since the

set up of AulaWeb has been a long process and we

cannot include everything here. But we cannot claim

we are experimenting e-learning. AulaWeb, in fact, is

mostly used as (1) a repository for learning material

(mostly PDF or PowerPoint files); (2) a communica-

tion tool (mainly through forums); (3) an assessment

tool (mainly through quizzes and assignments).

However, according to Martin Dougiamas

7

talk in

Rome in October 2008, we are part of a large com-

munity since these are the features used by 80% of

the users of Moodle, although the software platform

offers many other functionalities. This fact makes us

sharing the same “problem” that we can state as fol-

lows: “Why our users cannot exploit all the available

Moodle functionalities?”

6

There is an important difference here since software

testing is usually done before delivering while students eval-

uation is done in the last phase of WEL.

7

M. Dougiamas is the principal developer of Moodle.

AULAWEB, WEB-BASED LEARNING AS A COMMODITY - The experience of the University of Genova

45

Personally, we think that the technology is extremely

in advance with respect to the competences of the av-

erage user, specially when thinking to educators at

the university or at any school level. Indeed, sophis-

ticated e-learning experiences do exist but these are

mostly provided by early adopters, technology ad-

dicted, online universities, or by companies that have

professional training in their core business.

In our case, for example, the Faculty of Foreign

Languages plays the role of an early adopter since

it already delivers two online Masters but, on the

large scale, AulaWeb is a service offered to an ethero-

geneous population with different backgrounds, dif-

ferent ages, different attidutes (or fear) towards ICT

technologies. Therefore we thought it was not rea-

sonable to introduce from the beginning Web 2.0

technologies to users that hardly produce PDF files,

send empty e-mails with Word attachments or are not

aware of the fact that, since bandwidth is large but fi-

nite, collections of images should be resized before

being uploaded on a server, to make a few examples.

We decided to start with a low profile approach,

gradually introducing the software platform and its

basic functionalities without imposing any advanced

solution or asking any extreme effort. The original

idea was that of proposing AulaWeb as a software tool

available on demand and we think we have reached

our goal. Nowadays AulaWeb starts to be considered

a commodity, like the file system or the e-mail service,

something we can trust on since it is available by de-

fault. Time is now mature to offer advanced experi-

mentations, like the WEL action, to those colleagues

willing to improve their skills, but several problems

still remain open.

1. Online activities strongly depend on the availabil-

ity of online tutors, specially when dealing with

courses with large numbers of students. A single

teacher, in fact, can deal with small virtual classes

while the amount of work becomes unmanageable

with large ones.

2. Universities should define shared rules to ac-

knowledge online activities. Up to now, we are

not ready to account the time spent by the teach-

ers for the preparation of digital material and the

time spent online. The same situation holds for

students and we need to define a policy to evalu-

ate their online activities. At the moment, the type

of evaluation is not shared but it is a choice left to

the individual teacher.

3. Teaching models for subjects rather than On-

line Communication Strategies, Computer Sci-

ence subjects, E-learning subjects, Foreign Lan-

guages, . . . should be refined. Consider the case of

subjects like Termodynamics, Ancient History or

Urban Sociology. Are there any available records

of best practices in these cases?

4. Educating the educators is fundamental. Proba-

bly nowadays many of them do not have any dif-

ficulties in using web-based technologies but the

majority is not aware of Web 2.0 opportunities.

5. Last but not least, technical staff should be prop-

erly trained since the technology evolves too fast.

We end this work by observing that many definitions

exist to indicate the process of learning coupled with

ICT: blended learning, e-learning, web-based learn-

ing, technology enhanced learning, networked col-

laborative learning, i-learning (where ”i” stands for

Internet), I-learning (where ”I” denotes collaborative

learning in the Web 2.0 spirit). We think that educa-

tional techonologies cannot be considered any longer

as new technologies and when they will truly be-

come a commodity, then the term Learning should be

enough.

REFERENCES

Cole, J. and Foster, H. (2007). Using Moodle. Teaching

with the Popular Open Source Course Management

System. O’Reilly Community Press. Free online edi-

tion.

Dick, W. and Carey, W. (1996). The Systematic Design of

Instruction. New York: Haper Collins College Pub-

lishers.

Norman, D. (1998). The Design of Everyday Things. MIT

Press. Reprint edition.

O’Reilly, T. (2005). What Is Web 2.0. Design Patterns and

Business Models for the Next Generation of Software.

http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/-

09/30/what-is-web-20.html.

Trentin, G. (2001). Designing Online Courses. In Maddux,

C. and Johnson, D. L., editors, The Web in Higher Ed-

ucation: Assessing the Impact and Fulfilling the Po-

tential. The Haworth Press.

Trentin, G. (2007). Pedagogical Sustainability of Network-

Based Distance Education in University Teaching. In

Bailey, E., editor, Focus on Distance Education De-

velopments. Nova Science, New York, USA.

Trentin, G. (2008). La sostenibilit

`

a didattico-formatica

dell’e-learning. Social networking e apprendimento

attivo. FrancoAngeli. in Italian.

Yueh, H.-P. and Hsu, S. (2008). Designing a Learning Man-

agement System to Support Instruction. Communica-

tions of the ACM, 51(4).

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

46