HOW GENDER ISSUES CAN INFLUENCE STUDYING

COMPUTER SCIENCE

Mirjana Ivanović, Zoran Putnik

Department of Mathematics and Informatics, Faculty of Science, University of Novi Sad, Serbia

Anja Šišarica, Zoran Budimac

Department of Mathematics and Informatics, Faculty of Science, University of Novi Sad, Serbia

Klaus Bothe

Institute of Informatics, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany

Keywords: Gender, Success Rate, Professional Ambitions, Professional Satisfaction.

Abstract: This paper presents a gender related research conducted at Department of Mathematics and Informatics,

Faculty of Science, University of Novi Sad; in order to explore the following points amongst female under-

graduate students: (i) general success rate, (ii) professional confidence, interests and ambitions, (iii) level of

satisfaction with the choice of studies, (iv) attitudes and beliefs towards the gender issue. The query resulted

in indicative statistical data, providing basis for future work and discussion, as a contribution to narrowing

of the gender gap within the field of Computer Science.

1 INTRODUCTION

Numerous researches shown a considerable lack of

female students enrolled in Computer Science stud-

ies at universities worldwide. A lot of research ana-

lyzed different domains of ICT, involving different

levels of education (Gunn, 2003), (Ilias, 2006),

(Gharibyan, 2008), or related to new directions in

education (Hughes, 2002), (Vekiri, 2008).

As stated in (Kilgore, 2006), in the USA, from

1995 to 2004, only 20% of BA degrees in CS were

awarded to women, with the percentage continu-

ously diminishing. Similar situation is in Australia

(Miliszewska, 2006), or European countries: Ger-

many (Vosseberg, 1999), Finland (Paloheimo,

2006), Holland (Prinsen, 2007), or Greece (Ilias,

2006). According to (Putnik, 2008), Serbia is also

facing this global problem. The fact is that women

who stay in the field discontinue their studies more

often than their male colleagues – the phenomenon

is known as “the shrinking pipeline”: even though

young girls are attracted by CS, the higher level of

education, the smaller is the proportion of female

students. Statistics show that only 22% of the em-

ployees in the science related fields are female,

which does not match their share in the work force.

Some of the causes of this occurrence are follow-

ing: (i) the intimidation with the male dominated

nature of a field of CS, (ii) the absence of female

role models (iii) the lack of respect towards female

professionals, (iv) the lack of confidence in the abili-

ties of female professionals, (v) social pressure not

to study CS, (vi) fear of combination of work and

family life in IT sector being problematic.

In addition, it has been reported that women are

more attracted to applications that benefit society

than in programming itself, and therefore, tend to

lose interest when this aspiration is not satisfied,

often because feeling restricted by somewhat ab-

stract curriculum (Fisher, 2006).

On the other hand, historically observing, female

researchers and programmers played a significant

role in founding of CS. In the forties women formed

a majority of the programmers. In the fifties and

sixties female researchers contributed in the devel-

opment of user interfaces (Ngambeki, 2006). A

question poses: what have influenced a serious

223

Ivanovi

´

c M., Putnik Z.,

ˇ

Si

ˇ

sarica A., Budimac Z. and Bothe K. (2009).

HOW GENDER ISSUES CAN INFLUENCE STUDYING COMPUTER SCIENCE.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 222-227

Copyright

c

SciTePress

Table 1: Number of female undergraduate students involved in the survey.

1

s

t

year 2

nd

year 3

rd

year 4

th

year

Number of participants 36 38 24 18

Table 2: Average success rate.

June 2008

6.00-7.00 7.00-8.00 8.00-9.00 9.00-10.00 Unknown

Year/Average mark

1

s

t

year 11.11% 27.78% 33.33% 5.56% 22.22%

2

nd

year - - 68.42 31.58% -

3

rd

year - 64.29% 35.71% - -

4

th

year - 33.33% 44.44% 22.22% -

deepening of the gender gap over the past few dec-

ades?

Authors suggest that the key factor was the arri-

val of the home PCs: computers became a popular

hobby for boys. This led to the situation where, the

female students enter introductory CS classes with

weaker programming skills and lack of computer

related background. Also, according to (Paloheimo,

2006), social pressure is the obstructing factor: “The

society does not actually prevent girls from access-

ing computers, but it has failed to introduce CS as a

feasible option to them”, and as a result, IT built a

strong image as the men’s playground.

What finally brings women to the table? The fol-

lowing was suggested: (i) the continuing presence of

computers in a way that women can comprehend the

versatility of computer use, (ii) support and encour-

agement by the female professionals in the field, (iii)

help in understanding different career possibilities in

IT, (iv) awakening of interest in math and science

from the early age (Fisher, 2006).

The goal of this research was to explore gender

influences on female undergraduate students at De-

partment of Mathematics and Informatics, Faculty of

Science, University of Novi Sad.

2 RELATED WORK

Beginning of the 21st century introduced a signifi-

cant number of research and expert papers associ-

ated to gender politics. In (Paloheimo, 2006), au-

thors state that “students perform far better if their

comfort level is high”. Students were divided into

groups of female, male and mixed groups. The

communication was observed, and surveyed. The

study reveals that in CS classes “typical gender dis-

tribution (majority male) lowers the comfort level of

all students in comparison to a case with even gen-

der distribution”, suggesting that both male and fe-

male students would benefit if more women studied

CS.

In (Kilgore, 2006) no differences in abilities or

ambitions between males and females are registered.

Gender differences were shown in how students

view the practical nature of engineering. “Men were

more likely to discuss and be attracted to the hands-

on possibilities: trying out ides in the real world”,

women were more likely to commit to “linking the-

ory and practice: designing and creating”.

In order to motivate and direct students in higher

education, it is of great relevance to recognize life

goals and attitudes towards profession (Ngambeki,

2006). Authors of the study analyzed personal and

professional identity formation and attitudes towards

learning amongst groups of female engineering and

non-engineering students. Interviewers asked ques-

tions such as: “Where do you want to go in life and

why? What have you learned in class that you feel

really applies to your life? What impact does your

field have on society? How and why did you choose

your field?” They came to the conclusion that ”stu-

dents develop more sophisticated ideas about learn-

ing process and about their life goals as they pro-

gress through their undergraduate years, but that

engineers have a clearer sense of professional iden-

tity than their non-engineering counterparts early

and throughout their undergraduate careers”.

Intriguing motives amongst female students for

studying CS have been reported in (Gharibyan,

2008), providing completely different point of view.

Author explored factors which attract women in

Armenia to the field of CS. Namely, at some repub-

lics of former Soviet Union, female population is

well represented in CS. Author explains that success

with the following: “In Armenian culture there is no

emphasis on having a job that one loves; there is a

determination to have a profession that will guaran-

tee a good living”. Moreover: “Armenians consider

themselves practical and reasonable, setting goals

reachable within their talents, abilities and circum-

stances, and do not have glamorized expectations of

life, therefore do not get disappointed easily and do

not give up when things get difficult”. As a result,

CS is one of the most popular fields in Armenia.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

224

Table 3: Expression of attitude towards curriculum.

Mean

value

Standard

Deviation

Statement

I am generally satisfied with my choice of studies. 4.27 0.86

I feel more comfortable with mathematical courses, rather than with CS courses. 2.87 1.59

Studies positively effected my intellectual development and interests. 4.29 0.95

Table 4: Interest in taken courses: the least preferred courses and the most preferred courses.

1

st

year 2

nd

year 3

rd

year 4

th

year

The least

preferred

courses

Math. Logic and Algebra,

Analysis, Financial Mathemat-

ics

Data Structures and Algo-

rithms, Math. Logic, Analysis,

Linear Algebra

Data Structures and

Algorithms, Numerical

Analysis

Differential Equa-

tions, Linear Algebra

The most

preferred

courses

Data Bases, Informa-

tion Systems, OO

Programming

Web design, Intro to E-

business, Data Structures and

Algorithms, Intro to Pro-

gramming

Computer Organization, OO

Programming, Data Structures

and Algorithms, Web Design,

Data Bases

Data Bases, Web De-

sign, E-learning, Infor-

mation systems

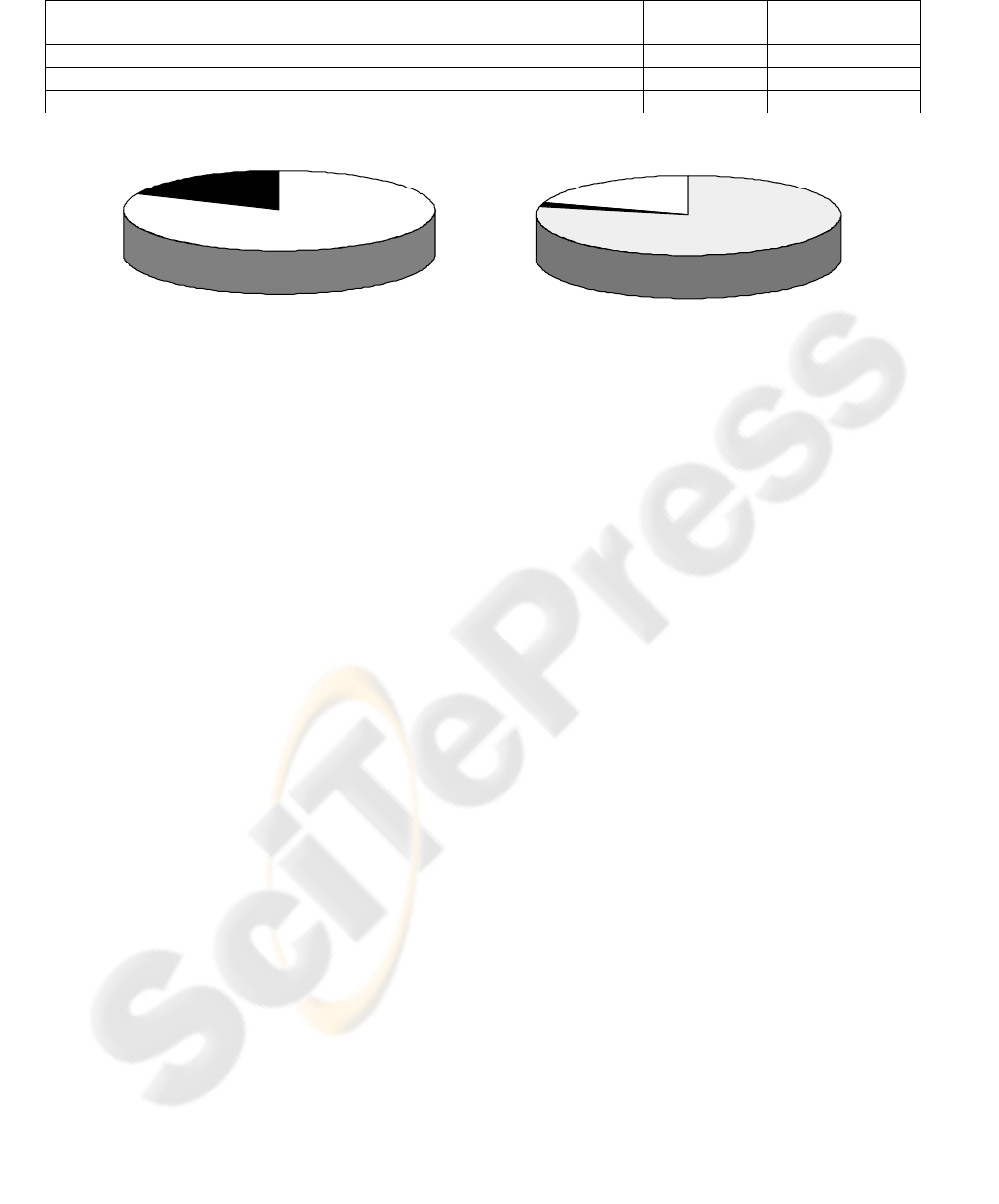

Figure 1: Results on question “What had the most influence on your choice of studies?”.

Gender related study was made at our Depart-

ment (Putnik, 2008), comparing success rates and

enrolment data of male and female students. Its find-

ings reveal a surprising fact: when it comes to tech-

nically-oriented courses, “there is no significant dif-

ference gender wise”. When it comes to business-

oriented courses, a difference in favour to women is

noted. Yet, female students did show an inclination

towards prejudices to some extent. Analysis of en-

rolment data in the same paper, reports that a con-

stant number of females enrol into “Business Infor-

matics” direction, while their number at “Theoretical

Informatics” direction is steadily decreasing and

there has not been a single female student enrolled

into “Teacher of Informatics” direction in the past.

3 METHODOLOGY, SURVEY,

COLLECTION OF DATA

The research presented here was conducted in June

2008, involving 116 female students of undergradu-

ate studies of Computer Science at our Department

(Table 1). The data was collected in the form of

questionnaire, focusing on the following topics:

interest in

computers and

informatics

45%

parents or

peers

5%

IT is future

15%

w ell-payed job

afterw ards

35%

c

• General studies success rate

• Satisfaction with the choice of studies

• Professional confidence, interests, ambitions

• Attitudes and beliefs towards the gender issue

Survey was anonymous. Participants were asked

to provide basic information: year of studies and

average mark, and answer descriptive questions:

• How do you imagine your job position after

the completion of your studies?

• On which job position do you see yourself in

10 years from now?

Participants were then asked to name the most

liked and disliked courses they had. It was followed

by three questions which required brief elaboration:

• What most influenced your choice of studies?

• Is IT a suitable field for women?

• Is it possible to have both successful career

and family?

Finally, nine questions were given in the form of

statements and participants responded on a Likert

scale of 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree),

HOW GENDER ISSUES CAN INFLUENCE STUDYING COMPUTER SCIENCE

225

Table 5: Expression of personal ambitions regarding career.

Standard De-

viation

Statement Mean value

Marks during studies are important to me. 3.66 1.05

I believe I am about to have a successful career. 4.31 0.78

I am worried about further course of my career after I complete my studies. 2.44

covering three key points of the research: expression

of personal ambitions regarding career; attitude to-

wards curriculum, and towards gender issue.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This Section summarizes the results gathered by the

survey:

4.1 General Success Rate

General success rate is given in Table 2. Grading

system for higher education in Serbia is in a form of

scale from 5 (failed) to 10 (outstanding excellence).

Bologna education system, introduced in 2006, re-

sulted in significantly higher passing rate and aver-

age success rate.

Notice that the 22.2% in the category Unknown

for the 1

st

year students is due to the fact that re-

search was conducted in June, before their first exam

period. Those who provided data referred to the out-

come of the winter semester.

4.2 Satisfaction with the Choice

of Studies

Students responded on a Likert scale of 1 (Strongly

Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), to the statements

presented in Table 3. We tried to determine the com-

fort level in studying and review effects of the stud-

ies on their intellectual development, and therefore

our influence as an education institution. Results

report it to be highly positive. Students have also

shown satisfaction with the choice of studies. An-

swers on both of statements are with low standard

deviation – even more encouraging.

Table 6: Personal ambitions after completion of studies.

Typical answers 1

st

year 2

nd

year 3

rd

year 4

th

year

Working in education 4 12 - -

Working in private business 2 4 2 2

Programmer, code writing 8 - 4 2

Working in a bank 4 2 10 4

Related to Data Bases - 4 6 4

Related to Web programming 2 4 - 2

Manager - 2 2 -

Researcher - 2 - 2

Going abroad - 4 - -

Related to SE - - - 2

Unknown 16 14 6 2

1.26

not sure

26%

other

10%

researcher

3%

professor

14%

in the private

business

22%

leading

positions

6%

in a bank

6%

the same as

after

completion of

studies 13%

Figure 2: Results on question “On which job position do you see yourself 10 years from now?”.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

226

Table 7: Expression of attitude towards the gender issue.

Standard Devia-

tion

Statement Mean value

Professionally, I feel completely equal to my male colleagues. 4.37 0.91

Authors in (Fisher, 2006) suggested that girls are

more inclined to mathematical than informatics re-

lated subjects. Obtained results indicate differently,

but not strongly convincing – mean value is just

about the middle (2.87), with high standard devia-

tion (1.59). To support these claims, Table 4 illus-

trates expressed interest in taken courses, where

mathematical courses often take place in the list of

less popular. It can also be noticed that some of the

courses go from category of “the most preferred” to

the category “the least preferred” courses, as stu-

dents advance through study years, as in case of

“Data Structures and Algorithms”.

Data about the motives for their choice of studies

are given in Fig. 1. Compared to results of the study

in Armenia, we can notice that well-paid job as a

motive is as influential as in this former Soviet Un-

ion republic. We also detect lower significance paid

to parents` or peers` influence.

In order to explore these ambitions in more de-

tail, participants were asked to describe on which job

position they see themselves after completion of

studies (Table 6), and then, in comparison, where do

they imagine themselves 10 years from now.

4.3 Professional Confidence, Interests

and Ambitions

Insight into students` point of view regarding their

professional future is given in Table 5. Marks seem

to be lower priority than expected, consulting high

general success rate. They also seem to be very con-

fident in the realization of their career objectives and

professional security and integrity.

Most popular options seem to be job in a bank

and working with data bases. It seems that, as a con-

sequence of rather conservative, male-oriented soci-

ety in Serbia, only few participants in their answers

mentioned terms such as “taking over leading posi-

tions”, “multidisciplinary approach”, “possibility of

further education and professional growth”. We also

report very low interest in research. Reason for such

attitudes could be a focus of some future work at our

Department. Another interesting point is that surpris-

ing number of the participants in this research ex-

pressed a wish to work as a teacher, while none of

them is enrolled in “Professor of Informatics” direc-

tion.

Teachers’ positions, especially in elementary and

secondary schools, are rather low-paid but on the

other hand very secure and somehow protected in

Serbia, as in most other countries. Also, it can be

noticed that almost none of the girls in senior years

used term “programmer” when describing their fu-

ture goals. Also, term “software engineering” is only

once mentioned. Group of answers classified in

“Unknown” includes such as “it is too early to think

that far”. It is comforting that the share of such re-

sponses is decreasing with the year of studies.

How our students see themselves 10 years from

now shows Fig. 2. Rather low number of students

12.7% gave answer “the same as after the comple-

tion of studies”, supporting claim stated in

(Gharibyan, 2008): by business owners, women are

seen as more loyal, dedicated and less ambitious.

yes

81,7%

not sure

18,3%

Concern regarding the lack of women in IT is justified.

yes

78%

no

2%

not sure

20%

2.62 1.33

Stereotypes regarding women in IT do not manifest in real life. 4.04 1.21

Figure 3: Results on question “Is it possible to combine IT career and family life?” and “Is IT a suitable field for

women?”.

HOW GENDER ISSUES CAN INFLUENCE STUDYING COMPUTER SCIENCE

227

4.4 Attitudes towards

the Gender Issue

Figure 3 shows that 81,7% of the participants be-

lieve that it is possible to combine IT career and

family life, not a single one responding negatively.

This is a little bit in contrary to previously obtained

answers and non-ambitious for further advancement

in professional life and continuation of education.

When asked “Is IT a suitable field for women?”,

almost none gave negative answer (Fig. 4).

More surprising data comes from Table 7, where

girls tend to diminish the presence of the gender

issue, although the statistics very argumentative in-

dicate opposite (Putnik, 2008). These numbers re-

veal remarkably high level of confidence, comfort

and gender self-awareness related to professional

skills amongst the participants.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented results that reflect the gender

climate at the Department of Mathematics and In-

formatics, at Faculty of Science, University of Novi

Sad, with the focus on (i) the comfort level, (ii) the

confidence level, (iii) the success level; amongst

undergraduate female students of all CS directions.

The research revealed that female CS students

show surprisingly high level of gender self-

awareness and confidence. Participants expressed

serious and ambitious attitudes regarding their career

objectives, feeling professionally equal to their male

colleagues, with their marks to prove those claims.

The comfort level considering their studies and fu-

ture professional growth is also on a satisfactory

level, even though the number of female students is

dropping each year, those who manage to complete

their studies, prove to be as competitive and skilful

as their male colleagues.

This could partially be explained by the fact that

technical skills are gender-blind, and as a conse-

quence, CS as such “bears more promises for equity

between genders in opportunities, positions and fi-

nally salary, than the other fields” (Putnik, 2008).

To conclude, our findings show that it is neces-

sary to make an effort to improve education politics

and attract more female students both at undergradu-

ate level, and postgraduate level.

REFERENCES

Fisher M., 2006. Gender and Programming Contests:

Mitigating Exclusionary Practices”, Informatics in

Education, Vol. 5, No. 1, 47–62.

Gharibyan H., 2008. Work in Progress – Women in Com-

puter Science: Why There Is No Problem in One For-

mer Soviet Republic”, Work in Progress, Computer

Science Department, California Polytechnic State

University.

Gunn C., 2003. Dominant or Different? Gender Issues in

Computer Supported Learning, JALN, Volume 7, Issue

1, pp.14-30.

Hughes G,, 2002. Gender issues in computer-supported

learning: What we can learn from the gender; science

and technology literature, ALT-J Research in Learning

Technology, Volume 10, Issue 2, pp. 77 – 79.

Kilgore D., Yasuhara K., Saleem J. J., Atman J. C., 2006.

What brings women to the table? Female and Male

Students` Perceptions of Ways of Thinking in Engi-

neering Study and Practice, Frontiers in Education

Conference, 36th Annual Volume , Issue , 27-31,

Page(s):1 – 6.

Ilias A., Kordaki M., 2006. Undergraduate Studies in

Computer Science and Engineering: Gender Issues,

The SIGCSE Bulletin, Volume 38, Nr 2, pp.81-85.

Miliszewska I., Barker G., Henderson F. Sztendur E.,

2006. The Issue of Gender Equity in Computer Sci-

ence – What Students Say, Journal of Information

Technology Education, Volume 5, pp. 107-120.

Ngambeki I., Rua A., Riley D., 2006. Work in Progress:

Sojourns and Pathways: Personal and Professional

Identity Formation and Attitudes Toward Learning

Among College Women, Work in Progress, Picker

Engineering Program, Smith College, Northampton.

Paloheimo A., Stenman J., 2006. Gender, Communication

and Comfort Level in Higher Level Computer Science

Education – Case Study, Frontiers in Education Con-

ference, 36th Annual, Issue 27-31, pp. 13–18.

Prinsen F.R., Volman M.L.L., Terwel J., 2007. Gender-

related differences in computer-mediated communica-

tion and computer-supported collaborative learning,

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, Volume 23

Issue 5, pp. 393 – 409.

Putnik Z., Ivanovic M., Budimac Z., 2008. Gender Related

Issues Associated to Computer Science Students,

Proc. of 6th International Symposium on Intelligent

Systems and Informatics (SISY 2008), Subotica, Ser-

bia, p. 5.

Vekiri I., Chronaki A., 2008. Gender issues in technology

use: Perceived social support, computer self-efficacy

and value beliefs, and computer use beyond school,

Computers & Education, Volume 51, Issue 3, pp

1392-1404.

Vosseberg, K., Oechtering, V., 1999. Changing the uni-

versity education of computer science, Technology

and Society, Proc. of Intl. Symposium Women and

Technology: Historical, Societal, and Professional

Perspectives, Volume, Issue, pp.73 – 79.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

228