WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM

DEALING WITH NOTATIONAL VARIANT SELECTION

Aya Nishikawa, Ryo Nishimura, Yasuhiko Watanabe and Yoshihiro Okada

Ryukoku University, Dep. of Media Informatics, Seta, Otsu, Shiga, Japan

Keywords:

Writing support system, Dominant notational variant, κ values.

Abstract:

In Japanese, there are a large number of notational variants of words. This is because Japanese words are writ-

ten in three kinds of characters: Kanji (Chinese) characters, Hiragara letters, and Katakana letters. Japanese

students study basic rules of Japanese writing in school for many years. However, it is difficult to learn which

notational variant is suitable for official, business, and technical documents because the rules have many ex-

ceptions. From the viewpoint of information retrieval, a considerable number of studies have been made on

notational variants, however, previous Japanese writing support systems were not concerned with them suf-

ficiently. This is because their main purposes were misspelling detection. Nondominant notational variants

are not misspelling, but often unsuitable for official, business, or technical documents. To solve this problem,

we developed a writing support system which detects nondominant notational variants in students’ reports and

shows dominant ones to the students. This system is based on the idea that suitable notational variants are

used dominantly in official, business, and technical documents. In this study, we first show the diversity of

notational variants of Japanese words and how to develop notational variant dictionaries by which our system

determines which notational variant is dominant in official, business, and technical documents. Finally, we

conducted a control experiment and show the effectiveness of our system.

1 INTRODUCTION

In English, there are few words which are spelled in

several different ways, such as, color and colour. In

contrast, in Japanese, there are a large number of no-

tational variants of words. This is because Japanese

words are written in three kinds of characters:

• Kanji (Chinese) characters,

• Hiragara letters, and

• Katakana letters.

For example, sakura [cherry blossom], one of the

symbols of Japan, is written in three ways, as shown

in Figure 1. Basic rules of Japanese writing are an-

nounced by the Cabinet, and Japanese students study

them in school for many years. However, it is dif-

ficult to learn the rules because they have many ex-

ceptions. In fact, we often find the confusion of no-

tational variants in Japanese university students’ re-

ports, including unsuitable notational variants for of-

ficial, business, and technical documents. As a result,

it is important for students to learn which notational

variant is suitable for official, business, and technical

Figure 1: Notational variants of sakura.

documents. To solve this problem, we developed a

writing support system which detects unsuitable no-

tational variants in students’ reports and shows suit-

able ones to the students. In this study, we assumed

that suitable notational variants are used dominantly

in official, business, and technical documents, on the

other hand, unsuitable ones are inferior or not found

in these documents. If the assumption is proper, un-

suitable notational variants can be detected by con-

73

Nishikawa A., Nishimura R., Watanabe Y. and Okada Y. (2009).

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM DEALING WITH NOTATIONAL VARIANT SELECTION.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 73-80

DOI: 10.5220/0001973800730080

Copyright

c

SciTePress

names of plants Hiragana Katakana Kanji+

sakura [cherry blossom] 184 39 736

bara [rose] 0 217 0

himawari [sun flower] 42 8 0

tsubaki [camellia] 9 25 83

tsutsuji [azalea] 5 15 0

ringo [apple] 8 71 10

mikan [orange] 66 37 2

Figure 2: The frequencies of notational variants of nouns

(plant names) in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspa-

per (Jan. 2006 – June 2006)].

firming whether they are used dominantly in official,

business, and technical documents. In this study, we

will use the term dominant notational variant of a

word to refer to the most frequent notational variant

of the word. Furthermore, our system shows the fre-

quencies of notational variants to the students because

they are objective and concrete measures. As a result,

the system gives the students chances to consider the

reasons why they used nondominant notational vari-

ants. There are two reasons why our system does not

replace nondominant notational variants to dominant

ones automatically.

• it is not appropriate to restrict the use of nondom-

inant notational variants because the use of nota-

tional variants is one of the sources of the richness

of Japanese expressions.

• it is important to consider the reasons why they

used nondominant notational variants and choose

suitable ones, especially, in educational institu-

tions.

From the viewpoint of information retrieval, a

considerable number of studies have been made

on notational variants (Kubomura 03) (Kouda 06)

(Bamba 08), however, spell checkers in Japanese

word processor, such as Microsoft word 2007, and

previous Japanese writing support systems were not

concerned with notational variants sufficiently (Shi-

momura 92) (Araki 93) (Murata 01). This is because

their main purposes were misspelling detection. Non-

dominant notational variants are not misspelling, but

often unsuitable for official, business, or technical

documents. In contrast, Yokoyama dealt with vari-

ants of Kanji characters (Yokoyama 06), but not with

variants of words. Furthermore, he did not consider

this variant problem from the viewpoint of document

domains. Dominant notational variants may varywith

document domains. For example, in newspaper arti-

cles, sakura is dominantly written in a Kanji charac-

ter, on the other hand, in documents in biology, it is

dominantly written in Katakana letters. Our system

can deal with this problem flexibly by switching dic-

tionaries of notational variants, which were developed

connection words Hiragana Kanji+

tatoeba [for example] 273 570

shitagatte [consequently] 21 26

tadasi [however] 343 0

ippou [on the contrary] 1 2879

mata [also, in addition] 4895 8

sarani [furthermore] 2677 24

Figure 3: The frequencies of notational variants of connec-

tion words in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspaper

(Jan. 2006 – June 2006)].

by using official, business, and technical documents

in several domains.

2 NOTATIONAL VARIANTS OF

JAPANESE WORDS

In this section, in order to show the diversity of no-

tational variants of Japanese words, we will show no-

tational variants of nouns, connection words, and de-

clinable words.

2.1 Notational Variants of Japanese

Nouns

In case of Japanese nouns, notational variants can be

classified into three types:

• words consist of Hiragana letters,

• words consist of Katakana letters, and

• words consist of Kanji characters and occasion-

ally Hiragana and Katakana letters.

Figure 2 shows the frequencies of notational variants

of plant names in the Mainichi newspaper articles

(Jan. 2006 – June 2006). As shown in Figure 2, dom-

inant ways of writing plant names are inconsistent.

2.2 Notational Variants of Japanese

Connection Words

Connection words are important words in students’

reports because they make the relationships between

sentences and ideas smoother and clearer. In case of

Japanese connection words, notational variants can be

classified into two types:

• words consist of Hiragana letters, and

• words consist of Kanji characters and occasion-

ally Hiragana letters.

Figure 3 shows the frequencies of notational variants

of connection words in the Mainichi newspaper arti-

cles (Jan. 2006 – June 2006). As shown in Figure

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

74

declinable words Hiragana Katakana Kanji+

yasashii [easy] 188 0 9

muzukashii [hard] 21 0 1524

(a) The frequencies of antonymous words:

yasashii [easy] and muzukashii [hard].

declinable words Hiragana Kanji+ (1) Kanji+ (2)

mijikai [short] mijikai mijika-i miji-kai

0 362 0

okonau [conduct] okonau okona-u oko-nau

15 9 2152

kawaru [change] kawaru kawa-ru ka-waru

15 9 2152

arawasu [show] arawasu arawa-su ara-wasu

7 283 1

(b) The frequencies of declinable words with declensional

Kana ending. Declensional Kana endings of Kanji+(1)

are shorter than those of Kanji+(2). Bold letters repre-

sent Kanji characters.

Figure 4: The frequencies of notational variants of declin-

able words in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspaper

(Jan. 2006 – June 2006)].

3, dominant ways of writing connection words are in-

consistent.

2.3 Notational Variants of Japanese

Declinable Words

In case of Japanese declinable words, notational vari-

ants can be classified into three types:

• words consist of Hiragana letters,

• words consist of Katakana letters with Hiragana

letters “suru”, and

• words consist of Kanji characters with declen-

sional Kana (Hiragana) ending.

Figure 4 (a) shows the frequencies of notational

variants of antonymous words, yasashii [easy] and

muzukashii [hard], in the Mainichi newspaper arti-

cles (Jan. 2006 – June 2006). Yasashii [easy] is

dominantly written in Hiragana letters, on the other

hand, muzukashii [hard] is dominantly written in

Kanji characters with declensional Kana (Hiragana)

ending. In other words, the contrast between yasashii

[easy] and muzukashii [hard] is broken from the view-

point of the dominant way of writing.

1

Both yasashii

[easy] and muzukashii [hard] have one type of declen-

sional Kana ending: -shii. As a result, they have one

variant with declensional Kana ending, yasa-shii and

muzuka-shii, respectively.

2

However, considerable

1

One of the authors dislikes this violation of the contrast

and always writes muzukashii [hard] in Hiragana letters in

his works.

2

Bold letters represent Kanji characters.

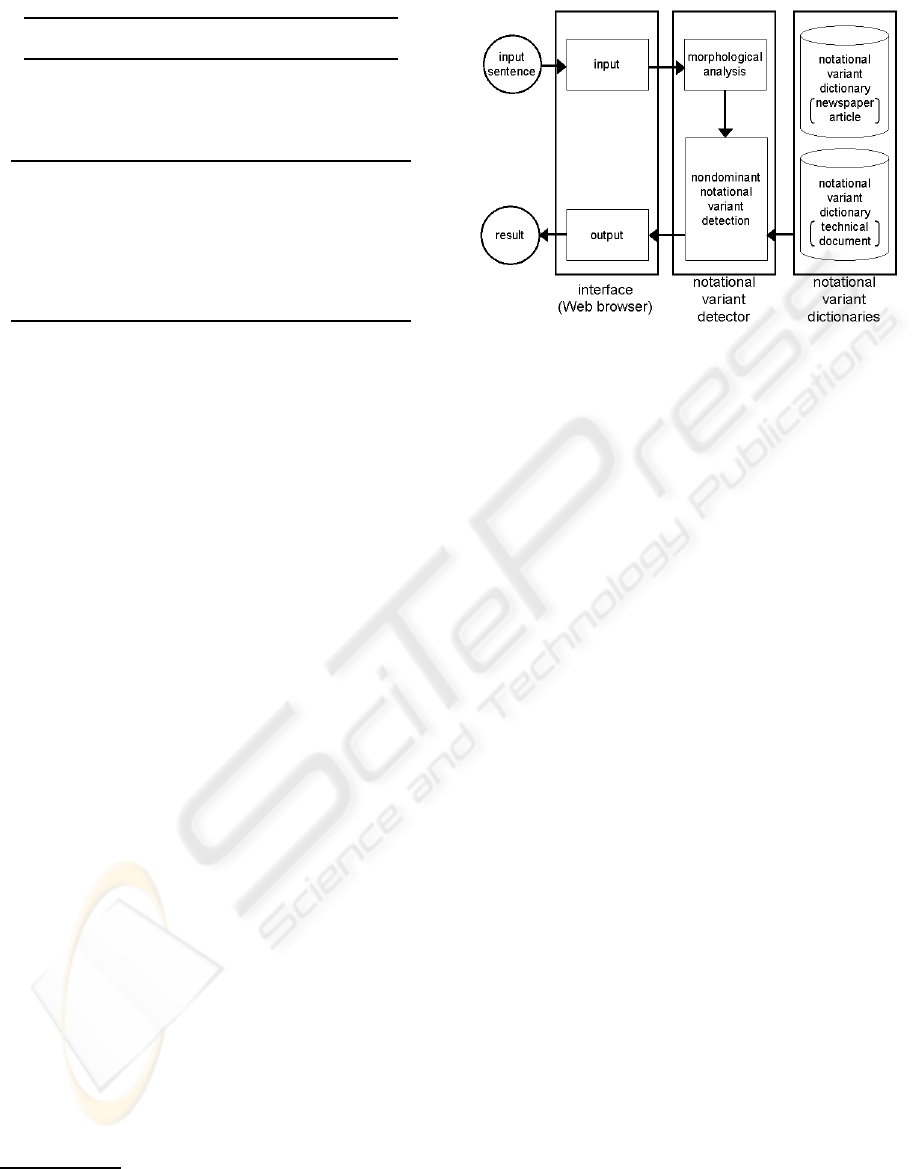

Figure 5: System overview.

number of declinable words have two types of de-

clensional Kana ending, and as a result, two variants

with declensional Kana ending. For example, kawaru

[change] has two types of declensional Kana ending,

-ru and -waru. As a result, kawaru [change] has two

variants with declensional Kana ending, kawa-ru and

ka-waru. Figure 4 (b) shows the frequencies of nota-

tional variants of declinable words with declensional

Kana ending in the Mainichi newspaper articles (Jan.

2006 – June 2006). It also shows that dominant ways

of writing declensional Kana ending are inconsistent.

Declensional Kana ending is one of the most trou-

bling aspect of notational variants. Japanese students

often feel confusionsabout declensional Kana ending.

As a result, we are often confronted with the confu-

sion of declensional Kana ending in their reports.

3 WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM

BASED ON NOTATIONAL

VARIANT DICTIONARIES

3.1 System Overview

Figure 5 shows the overview of our system. Our sys-

tem is based on the idea that suitable notational vari-

ants are used dominantly in official, business, and

technical documents. Figure 6 shows an example of

how to use our writing support system. As shown in

Figure 6, users can access and send input sentences

to the system via web browsers by using CGI based

HTML forms. Input sentences are segmented into

words by using a Japanese morphological analyzer,

JUMAN (Kurohashi 05). Then, by using notational

variant dictionaries, the system confirms whether no-

tational variants of the words are used dominantly in

official, business, and technical documents. When

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM DEALING WITH NOTATIONAL VARIANT SELECTION

75

(a) An input sentence, tabako wo yameru no ha muzukashii [it is hard to stop smoking], is given to the system.

(b) The system detects a nondominant notational variant, muzukashii [hard], in the input sentence and shows the fre-

quency information of the word in the newspaper articles and technical documents.

Figure 6: An example of how to use our writing support system. English system messages are inserted ad hoc for convenience

of non-Japanese readers of this paper.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

76

the system detects a nondominant notational variant

of a word in an input sentence, it is underlined and

turns red, and the system shows the frequency infor-

mation of notational variants of the word and gives

users chances to consider the reasons why they used

nondominant variants. In Figure 6 (a), a user gives an

input sentence, tabako wo yameru no ha muzukashii

[it is hard to stop smoking], to the system. Then,

as shown in Figure 6 (b), the system detects a non-

dominant notational variant, muzukashii [hard], in the

input sentence. muzukashii [hard] is underlined and

turns red, and the frequency information is shown. In

this way, the key to detecting nondominant notational

variants is notational variant dictionaries. In section

3.2, we show how to develop notational variant dic-

tionaries.

3.2 Development of Notational Variant

Dictionaries

In this study, we assumed that suitable notational vari-

ants are used dominantly in official, business, or tech-

nical documents, on the other hand, unsuitable ones

are inferior or not found in these documents. If the as-

sumption is proper, unsuitable notational variants can

be detected by confirming whether they are used dom-

inantly in official, business, or technical documents.

In order to confirm whether notational variants are

used dominantly, we extracted examples of notational

variants from

• 296364 newspaper articles published in the

Mainichi Newspaper from January 2006 to June

2006 (Mainichi 07).

• 319 technical reports published in the 12th Annual

Meeting of the Association for Natural Language

Processing (2006).

and developed notational variant dictionaries. In this

study, we used newspaper articles because we aimed

to acquire notational variants of words which used in

various domains. On the other hand, we used tech-

nical reports because we aimed to acquire notational

variants of words in specific domains and develop do-

main specific dictionaries of notational variants. The

reason why we developed domain specific dictionar-

ies of notational variants was that dominant nota-

tional variants may vary with document domains. By

switching domain specific dictionaries of notational

variants, our system can confirm whether notational

variants are suitable to compose documents in the spe-

cific domains. In this study, we acquired notational

variants in a specific domain from technical reports

published in the Annual Meeting of the Association

for Natural Language Processing (2006). Some of the

technical reports were given to the students, who took

part in the experiment described in Section 4, as ref-

erence works. This is one reason why we extracted

examples of notational variants from the technical re-

ports. Sentences in these documents were segmented

into words by using a Japanese morphological ana-

lyzer, JUMAN (Kurohashi 05). When JUMAN finds

a notational variant, it gives a variant label to the vari-

ant. The same variant label is given to notational vari-

ants of a word. By using these variant labels, we ex-

tracted notational variants and developed two dictio-

naries of

• notational variants in newspaper articles, and

• notational variants in technical reports of natural

language processing.

Table 1 shows the results of the notational variant ex-

traction from newspaper articles and technical docu-

ments. The most frequent notational variant of each

word was considered as the dominant notational vari-

ant.

As shown in Table 1, notational variants of 27988

and 9211 words were extracted from the newspaper

articles and technical documents, respectively. These

words can be classified into two types:

TYPE I a word of this type has actually two or more

notational variants, however, only one of them

was found in the newspaper articles or technical

documents.

TYPE II a word of this type has two or more nota-

tional variants which were found in the newspaper

articles or technical documents.

Table 2 shows the unique and total number of no-

tational variants of TYPE II words in the newspa-

per articles and technical documents. In order to

show how much the dominant notational variant of

a word is used dominantly, we introduced dominant

degree. Suppose that a word has notational variant i

(i = 1, ··· ,N). The dominant degree of the word is

calculated as follows:

d =

f

d

N

∑

i=1

f

i

where d is the dominant degree of the word, f

i

and

f

d

are the frequencies of notational variant i and the

dominant notational variant of the word, respectively.

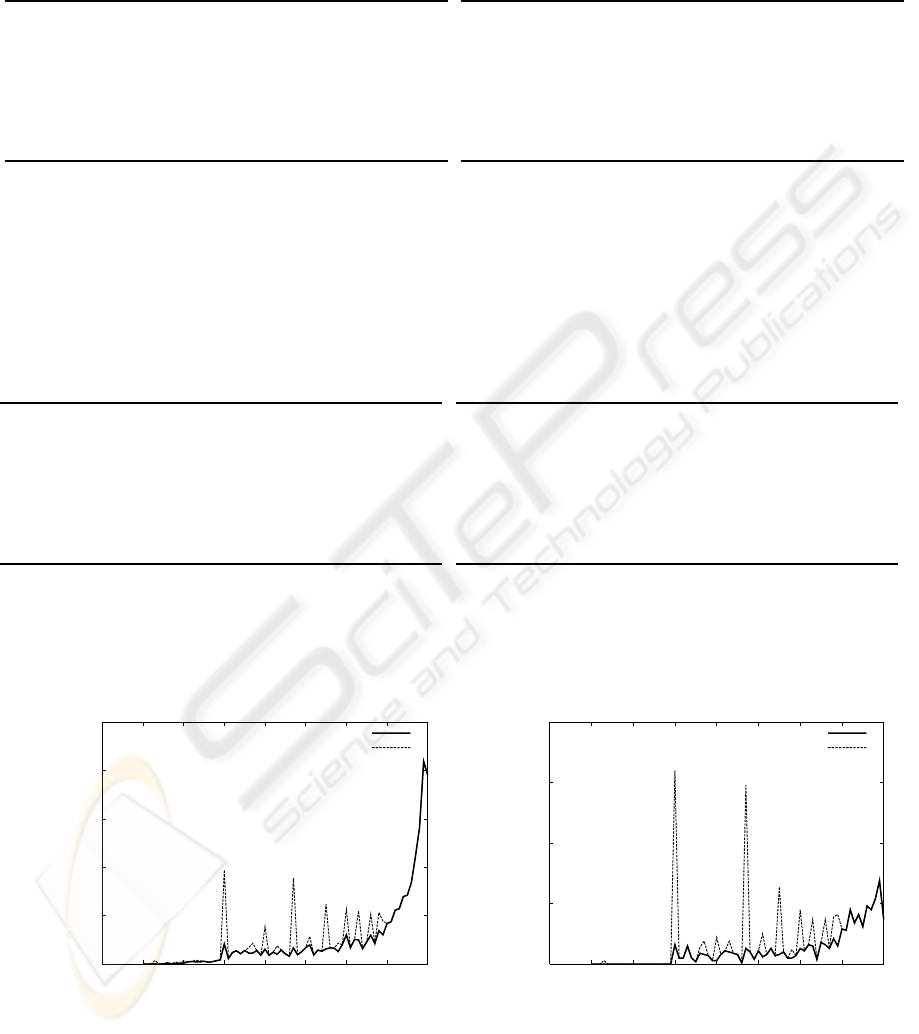

Figure 7 shows the histograms of the dominant de-

grees of TYPE II words in the newspaper articles and

technical documents. In Figure 7, the broken lines

showthe histograms of the dominantdegreesof all the

TYPE II words in the newspaper articles and technical

documents. On the other hand, the thick lines show

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM DEALING WITH NOTATIONAL VARIANT SELECTION

77

Table 1: The results of the notational variant extraction from the newspaper articles and technical documents.

unique # of unique # of total # of

part of words notational notational

speech (variant labels) variants variants

noun 20603 26747 3656574

verb 3897 6403 1283024

adjective 2120 2830 280787

adverb 1125 1607 115609

conjunction 87 100 30850

interjection 80 97 2643

attributive 75 98 10946

prefix 1 3 10891

Total 27988 37885 5391324

(a) The results of the notational variant extraction from

the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspaper (Jan.

2006 – June 2006)].

unique # of unique # of total # of

part of words notational notational

speech (variant labels) variants variants

noun 6458 7154 310980

verb 1548 2093 101398

adjective 706 825 22952

adverb 376 459 13037

conjunction 60 71 4465

interjection 30 33 148

attributive 32 39 1192

prefix 1 3 302

Total 9211 10677 454474

(b) The results of the notational variant extraction from

the technical documents [the Annual Meeting of the

Association for Natural Language Processing (2006)].

Table 2: The unique and total number of notational variants of TYPE II words in the newspaper articles and technical docu-

ments. A TYPE II word has two or more notational variants which were found in the newspaper articles / technical documents.

unique # of unique # of total # of

part of words notational notational

speech (variant labels) variants variants

noun 5328 11472 1817055

verb 2135 4641 916302

adjective 628 1338 176374

adverb 440 922 72251

conjunction 13 26 12980

interjection 15 32 593

attributive 22 45 8853

prefix 1 3 10891

Total 8582 18479 3015299

(a) The unique and total number of notational vari-

ants of TYPE II words in the newspaper articles

[Mainichi Newspaper (Jan. 2006 – June 2006)].

unique # of unique # of total # of

part of words notational notational

speech (variant labels) variants variants

noun 644 1340 62848

verb 508 1053 56058

adjective 110 229 6253

adverb 78 161 5617

conjunction 11 22 1330

interjection 3 6 13

attributive 7 14 941

prefix 1 3 302

Total 1362 2828 133362

(b) The unique and total number of notational variants

of TYPE II words in the technical documents [the

Annual Meeting of the Association for Natural Lan-

guage Processing (2006)].

0

200

400

600

800

1000

0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

word frequency

dominant degree

TYPE II words (used 10 times or more)

TYPE II words (all)

(a) The histograms of the dominant degrees of TYPE II

words in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspa-

per (Jan. 2006 – June 2006)].

0

50

100

150

200

0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

word frequency

dominant degree

TYPE II words (used 10 times or more)

TYPE II words (all)

(b) The histograms of the dominant degrees of TYPE II

words in the technical documents [the Annual Meet-

ing of the Association for Natural Language Pro-

cessing (2006)].

Figure 7: The histograms of the dominant degrees of TYPE II words in the newspaper articles and technical documents.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

78

the histograms of the dominant degrees of TYPE II

words the notational variants of which were used 10

times or more in the newspaper articles and technical

documents. The reason why we eliminated words the

notational variants of which were used less than 10

times in the newspaper articles and technical docu-

ments is that it is difficult to confirm which notational

variant is used dominantly because there were too few

samples. As a result, we thought that dominant nota-

tional variants were credible when they satisfy the fol-

lowing conditions, and gavecredibility labels to them.

• in case of a TYPE I word, the notational variant

of the word was used 10 times or more in the

newspaper articles or technical documents. 11825

and 2285 TYPE I words in the newspaper arti-

cles and technical documents, respectively, satis-

fied this condition.

• in case of a TYPE II word, the sum of frequencies

of all the variants of the word was 10 or more,

and the dominant degree was 0.8 or more. 5270

and 590 TYPE II words in the newspaper arti-

cles and technical documents, respectively, satis-

fied the above conditions.

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

To evaluate our method, we conducted a control ex-

periment. We gave 10 problems of notational variant

selection to 20 subjects, university students in com-

puter science. Each problem consisted of two sen-

tences. The differences between the two sentences

were only notational variants. For example, the fol-

lowing sentences mean that it is hard to stop smoking:

• tabako wo yameru noha muzukashii

• tabako wo yameru noha muzuka-shii

the differences between the two sentences above are

muzukashii and muzuka-shii. The former is written

in Hiragana letters and the latter is written in Kanji

Characters (in Bold letters) and Hiragana letters. The

subjects were requested to choose one of the sen-

tences, which seemed to be suitable for them to use

in official, business, and technical documents. Sub-

jects were classified into two groups, group A and B.

• subjects in group A were given only 10 problems

and no more information.

• subjects in group B were given the same 10 prob-

lems and frequency information of the notational

variants in the test materials.

The frequency information of the notational variants

were retrieved by our experimental writing support

system. As shown in Figure 6 (b), when our system

Table 3: Experimental results.

rate of choosing

group κ value dominant notational variants

group A 0.261 74%

group B 0.623 87%

Table 4: Interpretation of κ values.

κ Interpretation

< 0 no agreement

0.0 - 0.20 slight agreement

0.21 - 0.40 fair agreement

0.41 - 0.60 moderate agreement

0.61 - 0.80 substantial agreement

0.81 - 1.00 almost perfect agreement

detects a nondominant notational variant of a word in

an input sentence, it shows the frequency information

of notational variants of the word. For example, the

frequency information of muzukashii and muzuka-

shii was shown as follows:

newspaper articles muzukashii muzuka-shii

21 1524

technical reports muzukashii muzuka-shii

0 155

To evaluate the experimental results, we intro-

duced two measurement: κ values and the rate of

choosing dominant notational variants (Table 3). κ

values are statistical measures for assessing the re-

liability of agreement between subjects. κ values

are generally thought to be more robust than simple

percent agreement calculation, in this case, the rate

of choosing dominant notational variants, because κ

values take into account the agreement occurring by

chance. Table 4 shows the interpretation of κ values

(Landis 77). As shown in Table 3 and 4, in this exper-

iment, there was fair agreement of notational variant

selection in group A. In other words, we were con-

fronted with the confusion of notational variants in

their answers. In each problem, some students chose

a nondominant (unsuitable) notational variant for no

reason and they were totally unaware of doing it. It

shows that the notational variant selection is a seri-

ous problem. On the other hand, there was substantial

agreement in group B. In addition, we obtained 13 %

increase of the rate of choosing dominant notational

variants when the frequency information was given to

subjects. It shows that the frequency information of

notational variants is promising. It also implies that

students do not have confidence in their notational

variant selection and flexibly change their decisions

when the reasons are given to them. Actually, three

subjects in group B changed their decisions, and three

other subjects did not change but felt sure of their de-

cisions. Some of them said that they can obey sys-

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM DEALING WITH NOTATIONAL VARIANT SELECTION

79

tem’s advices more simply than teacher’s instructions

without concrete evidences. The other four subjects

in group B reported that the frequency information is

not necessary. Actually, one of them could choose

dominant variants correctly in all the problems, on the

other hand, the others could not. This is because they

obeyed a peculiar writing rule: they must use as many

Kanji characters as possible in their official, business,

and technical reports. This is the limitation of our

writing support system, and where a human instruc-

tor comes in.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been supported partly by the

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) under Grant

No.20500106.

REFERENCES

Kubomura and Kameda: Information Retrieval System with

Abilities of Processing Katakana-Allographs, Trans.

of IEICE, Vol.J86-D-II, No.3, (2003).

Kouda: Search method of variant notations on a science and

technology document retrieval system, IPSJ SIG NL,

Vol.2006, No.118, (1993).

Bamba, Shinzato, and Kurohashi: Development of a Large-

scale Web Page Clustering System using an Open

Search Engine Infrastructure TSUBAKI, IPSJ SIG

NL, Vol.2008, No.4, (1993).

Shimomura, Namiki, Nakagawa, and Takahashi: A method

for detecting errors in Japanese sentences based

on morphological analysis using minimal cost path

search, Trans. of IPSJ, Vol.33, No.4, (1992).

Araki, Ikehara, and Tukahara: A method for detect-

ing and correcting of characters wrongly substituted,

deleted or inserted in Japanese strings using 2nd-order

Markov model, IPSJ SIG NL, Vol.93, No.79, (1993).

Murata and Isahara: Extraction of negative examples based

on positive examples: automatic detection of mis-

spelled Japanese expressions and relative clauses that

do not have case relations with their heads, IPSJ SIG

NL, Vol.2001, No.69, (2001).

Yokoyama: Can we predict preference for kanji form from

newspaper data on character frequency?, IPSJ SIG

CH, Vol.2006, No.10, (2006).

Kurohashi and Kawahara: JUMAN Manual version 5.1 (in

Japanese), Kyoto University, (2005).

Mainichi Shinbun CD-Rom data set 2006, Nichigai Asso-

ciates Co., (2007).

Landis and Koch: The measurement of observer agreement

for categorical data, Biometrics, Vol. 33, (1977).

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

80