PERSONALIZATION IN HYPERMEDIA LANGUAGE

ASSESSMENT

J. Enrique Agudo, Mercedes Rico

Centro Universitario de Mérida, University of Extremadura, Santa Teresa de Jornet, 38, Mérida, Spain

Patricia Edwards

School of Business Science and Hospitality Studies, University of Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain

Héctor Sánchez

Centro Universitario de Mérida, University of Extremadura, Santa Teresa de Jornet, 38, Mérida, Spain

Keywords: Assessment, L2 learning, Hypermedia, e-Portfolio.

Abstract: Protocol technologies present a wide range of challenges for educators and learners, from course design to

teaching practices to assessment. Having moved beyond traditional teaching approaches, hypermedia,

enhancing a more goal directed learning format, grants people the chance to learn greater amounts of

information more quickly. In this context, academia needs to know how learning can be effectively

measured in technological environments. Regardless of the answer, it is essential to develop evaluation

systems that support all kinds of teaching and assessment practices. With this aim in mind, this paper

proposes two assessment methods which may best suit language learning in online environments: first,

architecture providing personalization services for adaptive educational hypermedia, and, second, the online

portfolio to measure performance based on collections of student-created work.

1 PERSONALIZATION

Personalized learning is receiving growing attention

from policy makers, theorists and practitioners in

order to properly address teaching different things to

different people (Sebba & Brown, 2007).

All too often, formal schooling is ruled by

policies based on the premise that most educational

problems are solved by a powerful testing system.

Such a system is rarely personalized as the tendency

is either to punish or reward students by simply

measuring high or low performance. Standardized

assessments aim at completing standardized test

packages based on concepts like overall reliability

and generalizability (J. D. Brown & Hudson, 1998).

Both notions indicate universal evaluation

measurement references rather than individualized

ones. However, every learner’s education and

personal background can be developed by attending

to his/her unique set of abilities, interests and needs,

and, by analogy, evaluating this type of learning.

Personalization thus, allows learners to obtain

information as adapted to their personal

characteristics. The first of these features is

identification of the user model employed to deliver

the main parameters for selecting and adapting the

information presented, and ultimately, evaluating it.

The concept of personalization means that the

individual is the center of the learning process.

Friedrichs & Gibson, (2001) claim personalization

consists of general competence concerned with

authenticity, the use of technology and the creation

of personalized problem-centered approaches.

Personalization in e-learning and technological

environments is currently a central issue challenging

the area of adapted learning, where multiple

parameters like context, methodology, content,

computer interaction, teaching/assessment practices

etc. are involved. Supporting personalized learning

in hypermedia environments requires, however,

expertise and coordinated efforts throughout the

whole learning process in order to improve

efficiency, cost effectiveness, virtual collaboration

123

Enrique Agudo J., Rico M., Edwards P. and Sánchez H. (2009).

PERSONALIZATION IN HYPERMEDIA LANGUAGE ASSESSMENT.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 123-126

DOI: 10.5220/0001976401230126

Copyright

c

SciTePress

and design of individualized learning paths. In

essence, this means assessment procedures need be a

mirror reflection of teaching-learning methods.

2 BACKGROUND

Hypermedia technology and educational virtual

environments are increasingly being used to create

instructional spaces for distance education. They

encourage learners through the experience of

visualizing concepts in order to carry out simulated

real world tasks, Costagliola et al (2005) claim the

use of visual language provides an intuitive and

user-friendly interface for e-learning practices.

Nonetheless, technologies present challenges for

educators and learners, ranging from teaching

methods to assessment protocols. Emerging

applications include interactive simulations,

hypermedia and virtual explorations, obliging

teachers to reconsider teaching practices (Jacobson

& Azevedo, 2008) by designing innovative online

activities and devising evaluation procedures to

assess avant-garde learning ways and means.

How then can learning be effectively measured

in technological environments with a personalized

perspective? Some authors contend that the

limitations of classic assessment models should be

replaced by new paradigms for assessment in online

learning, pointing out the e-portfolio as one of the

most feasible (Mateo & Sangrá, 2007). Others like

Boboc, Beebe, & Vonderwell (2006) place special

emphasis on the factors involved in highlighting

time management, the complexity of the course

content, and the structure of the online medium as

variables influencing the design of assessment

proposals. Other solutions are backed by those in

favor of scaffolding self-regulated learning,

metacognition and assessment in designing

computer-based tasks (Azevedo, & Hadwin, 2005),

or by scholars who advocate the intrinsic potential of

Web 2.0 to support collaborative learning and

facilitate feedback between teachers and students

(Russell, Elton, Swinglehurst, & Greenhalgh, 2006).

Despite a variety of possible answers, a cornerstone

concept lies in developing evaluation systems to

support all kinds of teaching and learning practices

focused on collaboration, interaction, and,

personalization in hypermedia teaching approaches.

In light of the discussion, it seems reasonable to

conclude that for diverse kinds of virtual instruction,

the conversion of conventional learning models into

adaptive environments with hypermedia applications

and online teaching platforms is but a must.

To pursue a form of evaluation rendering true

face validity guaranteeing personalization in learner

assessment processes, our paper advocates two

methods of alternative assessment suitable for

language learning in online environments: adaptive

hypermedia and the online portfolio.

3 ADAPTIVE HYPERMEDIA:

MEETING PERSONAL NEEDS,

ASSESSING PERSONAL

GOALS

Web-based assessment is widely used to support

student learning and aids in achieving goals like

self-assessment, peer assessment, and evaluation of

the learning process itself (Grimon, Monguet,

Fabregas, & Castelan, 2008). Such applications can

be further enhanced when assessment is learner

customized since individuals have different

preferences, needs and wants (Brusilovsky, 2001).

Adaptive Hypermedia Systems (AHS) are those

offering a computer-aided format for learning at the

learner’s pace, joining the virtues inherent to

hypertext and multimedia as well as containing all

kinds of multimedia material, i.e. text, sound,

images, video, etc. Furthermore, AHS allows and

invites the user to freely explore the available

content (De Bra, 2006).

Thus, if adaptive hypermedia presents content

adapted to the hierarchical and linear learning

preferences of the user, and it delivers content which

accommodates visual, verbal, and experiential

learning preferences, then, it stands to reason that

adaptation plays an important role in both increasing

learning-effectiveness and in assessing personal

abilities on the specific content.

Aspects of AHS adaptation, make it apparent

that hierarchical and linear structure is fundamental

(Kobsa, Koenemann, & Pohl, 2001).

The features of an AHS distinguish three types

of data: adaptation of user data, the data to be used,

and, the data of the environment (Kobsa et al.,

2001). User data is identified as objects of traditional

adaptation employing user’s specific characteristics.

The data of use houses information on user

interaction with the system which cannot be

otherwise solved by the user features. The data of

the environment refers to all the aspects within the

setting other than those related to the user. The three

constituents make up a trio of elements conducive to

personalized hypermedia language assessment.

GexCALL research group has developed an

adaptive system for primary school children learning

foreign languages through ICT (Rico, Agudo,

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

124

Edwards, & Cumbreño, 2007). Its architecture

required multimedia task design adapted to the

limited level of knowledge and special interaction

styles of young target users (Agudo, Sánchez, Rico,

& Domínguez, 2007). Six fundamental parameters

make up the user model in order to adapt learning

tasks to each individual child (Agudo, Sánchez, &

Rico, 2006): the child’s educational level regarding

the pedagogical domain, knowledge acquired intra-

process, psycho-motor capacity, foreign languages,

textual information, and level of difficulty.

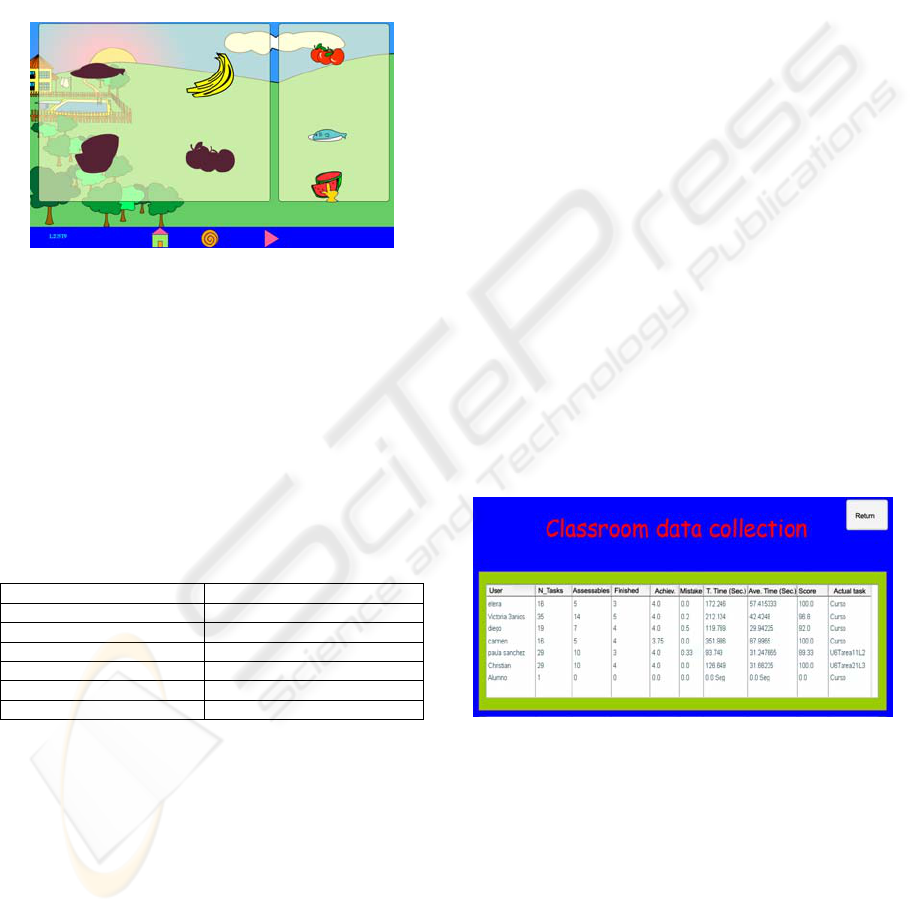

Figure 1: Evaluation Task example.

A sample task taken from the “Food” unit is

illustrated in figure 1. The objective lies in

identifying the foods introduced and then placing

them in the correct position in the shaded silhouette

on the screen. Technical details for the adaptation

parameters corresponding to this task are listed in

table 1, information collected from the user model.

Said parameters are transmitted to the Interface

via an XML file storing all information needed to

dynamically build the task.

Table 1: Task adaptation parameters.

PARAMETERS VALUE

Educational level 4 year-olds

Knowledge Level 1 passed

Interaction Level Level 2 (Click move)

Language English

Textual Information No

Difficulty Low (4 Elements)

4 PORTFOLIO ASSESSMENT:

RECORDING LEARNER DATA

Barret (2002) defines electronic portfolios as a new

kind of container providing an educational space for

participants to store, share and organize learning. As

a collection of personal student work, it houses

drafts of learner development records over time,

inventories focused on the process rather than on the

product, etc. Portfolios provide learners the chance

to show what they can do, they encourage students

to be reflective learners, and they help them take on

responsibility for their own progress. An added

bonus clearly different from traditional evaluation

methods, is that portfolios give both learners and

instructors the chance to collaborate and reflect on

work in the making as well as on the final product.

Portfolios use databases to collect observations

of learning activities in or outside of classrooms, log

learner task development and student interactions,

including records of conventional performance

assessments, grades, samples of student input and

output, interviews with parents /teachers /tutors, and

a very long etcetera (Chang, 2001).

In our adaptive system for primary school

children, implementation of the portfolio data for

assessment is a straightforward process. As the AHS

stores the results of every learner task, detailed

information is gathered on scores, correct answers,

errors and how long it has taken the learner to

complete each activity. The teacher can observe the

exact task being worked on as well as specific

information on tasks already completed.

Data recorded can be instructor accessed and

referenced. The wealth of information available

includes up-to-date records of how many tries are

needed for an individual to complete a task, the

resulting output of these efforts, how much work is

yet to be accomplished and summaries of student

output. The data not only provides an in-depth view

of personal learning processes, it also indicates

activities and concepts requiring reinforcement.

Figure 2: Global results.

Moreover, analysis of the group’s global results

(figure 2) shed light on learning aspects indicating

complementary assessment factors applicable to

personalization. Comparison with peer activity,

relative class rankings, percentile ratings, means and

averages, overall assessment of predominant task

simplicity or complexity, dedication in terms of time

spent on activities, among other findings, may serve

to unravel inquiries that aid in personalizing learner

assessment policies. For example, should the vast

majority of learners encounter excessive difficulty

PERSONALIZATION IN HYPERMEDIA LANGUAGE ASSESSMENT

125

with an assignment, the resulting data may be calling

for action regarding content or design rather than

evaluation of student performance on that task.

5 CONCLUSIONS

To answer the question addressing the establishment

of measures and methods for evaluating learning in

technological environments, our proposal identifies

adaptive hypermedia and portfolio assessment as

specific evaluation models to efficiently support

online teaching-learning practices.

The architecture of adaptive systems supplies

important benefits to educational applications, like

assigning grades in peer assessment, personally

guiding students in their learning process according

to their particular features, or helping them to make

decisions related to their individual performance.

Online portfolio assessment uses both qualitative

and quantitative techniques to provide reliability and

validity within the assessment process in online

teaching. By reporting on exploratory research into

designing information systems for online portfolios,

this paper also highlights the significant advantages

online portfolio information systems offer in

creating, distributing and assessing teaching to a

wide range of stakeholders in ways far superior to

other assessment solutions and tools.

The GexCALL system allows for adaptive

learning and evaluation by implementing a portfolio

that automatically tailors student completion of

interactive educational activities. Forthcoming is the

perfection of its interface to provide users with

handheld devices, virtual touch whiteboards and

video game consoles. The group user model will

allow for group interaction in collaborative

educational activities enriched by voice recognition.

REFERENCES

Agudo, J. E., Sánchez, H., & Rico, M. (2006). Adaptive

learning for very young learners. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, 4018, 393-397.

Agudo, J. E., Sánchez, H., Rico, M., & Domínguez, E.

(2007). Second Language Learning at Primary Levels

using Adaptive Computer Games. En Proceedings of

World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications (págs. 3848-

3857). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Azevedo, R., & Hadwin, A. F. (2005). Scaffolding self-

regulated learning and metacognition: Implications for

the design of computer-based scaffolds. Instructional

Science, 33, 367–379.

Barret, H. (2002). Presentation. En ISTE’s Forum on

Assessment and Technology, San Antonio, Texas.

Boboc, M., Beebe, R., & Vonderwell, S. (2006).

Assessment in Online Learning Environments:

Facilitators and Hindrances. En C. Crawford, D. A.

Willis, R. Carlsen, I. Gibson, K. McFerrin, J. Price, et

al. (Eds.), Society for Information Technology and

Teacher Education International Conference 2006

(págs. 257-261). Orlando, Florida, USA: AACE.

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (1998). Alternatives in

Language Assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 32(4), 653-

75.

Brusilovsky, P. (2001). Adaptive Hypermedia. User

Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 11(1), 87-

110.

Chang, C. (2001). Construction and Evaluation of a Web-

based Learning Portfolio System: An Electronic

Assessment Tool. Innovations in Education and

Teaching International, 38(2), 144-55.

Costagliola G., Ferrucci F., Polese G., and Scanniello G.,

(2005).A Visual Language Based System for

Designing and Presenting E-learning Courses".

International Journal of Distance Education

Technologies, vol. 3, (1), Idea Group Publishing.

De Bra, P. (2006). Web-based educational hypermedia. En

Data Mining in E-Learning (págs. 3-17). WIT Press.

Friedrichs, A., & Gibson, D. (2001). Personalization and

secondary school renewal. En J. DiMartino, J. Clarke,

& D. Wolf (Eds.), Personalized learning: Preparing

high school students to create their futures (págs. 41-

68). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Education.

Grimon, F., Monguet, J., Fabregas, J., & Castelan, E.

(2008). Experience with an Adaptive Hypermedia

System in a Blended-Learning Environment. In World

Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia

and Telecommunications 2008 (págs. 5627-5634).

AACE.

Jacobson, M & Azevedo, R (2008). Advances in

scaffolding learning with hypertext and hypermedia:

theoretical, empirical, and design issues. Educational

Technology Research and Development, Springer

Boston, Vol 56 (1), 1-3

Kobsa, A., Koenemann, J., & Pohl, W. (2001).

Personalized hypermedia presentation techniques for

improving online customer relationships. The

Knowledge Engineering Review, 16

(2), 111-155.

Rico, M., Agudo, J. E., Edwards, P., & Cumbreño, A. B.

(2007). Diseño y evaluación del uso de tecnologías en

la enseñanza del inglés en Educación Infantil. In Actas

VIII Simposio Nacional de Tecnologías de la

Información y las Comunicaciones en la Educación

(págs. 223-230). Thomson.

Russell, J., Elton, L., Swinglehurst, D., & Greenhalgh, T.

(2006). Using the Online Environment in Assessment

for Learning: A Case-Study of a Web-Based Course in

Primary Care. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher

Education, 31(4), 465-478.

Sebba, J., & Brown, N. (2007). An Investigation of

Personalised Learning Approaches used by Scholls,

Research Report RR843. Annesley, Nottingham:

University of Sussex.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

126