COMPUTER-BASED SIMULATOR TRAINING IN THE

HOSPITAL

A Structured Program for Surgical Residents

Minna Silvennoinen

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Teuvo Antikainen, Jukka-Pekka Mecklin

Department of Surgery, Central Finland Central Hospital, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Computer-based simulator training, Surgical skills, Surgical resident education.

Abstract: Rapid developments in techniques and new skills requirements have increased the need for surgical training

outside the operating room (OR). Simulator training is often seen as a vital part of the surgical resident’s

education. This paper presents a simulator training program aimed at providing surgical skills training for

residents in a hospital. The theoretical background on the subject is considered and initial findings

discussed. The results highlight the need to organize the training systematically. Simulator training prior to

entering the OR should be mandatory for all residents, even though the study showed the motivation for

voluntary participation to be high. The role of the specialist surgeon emerged as an essential element in the

simulator training, both as an evaluator and as an instructor.

1 INTRODUCTION

During their university studies, physicians are

provided with the basic knowledge and skills of

medicine. After graduation, those aiming to become

surgical residents have to work in hospitals for

another period of 5-6 years to achieve the level of a

specialist. The basic university teaching is

thoroughly planned, but the six years of learning for

specialization may well include no detailed learning

or teaching program, and tends to be dependent on

local circumstances. In many medical specialities

self-study via books or the Internet can compensate

for possible defects caused by inadequate training

programs. However, surgical skills cannot be

achieved by reading. Learning comes from

experience in the operating room (OR) or from a

simulated learning environment. At least in Finland,

hospitals are mainly organized to take care of

patients; the training of personnel is a secondary

task.

Video-assisted surgery has changed traditional

surgery and new skills are needed in the OR.

Laparoscopy refers to a surgical technique

performed in the abdominal cavity in which the

operation is conducted through small incisions, with

the surgeon viewing the operating area from a video-

screen. Laparoscopic operations have proved to be

more difficult than traditional open surgery, for both

experienced and novice surgeons (Madan et al.,

2004; Soper et al., 1994). Rapid developments in

equipment have increased the time needed to learn

surgical procedures. There is thus a need to construct

teaching protocols (Reznick and McRae, 2006) that

are not only more effective in themselves, but also

capable of being embedded within fluent,

economical and routine organizational processes.

Simulator training has been introduced as one

solution that can help to solve the problem of

reducing the time needed to train residents in

acquiring the complex skills in question. Most

residents began their residency without any manual

skills in laparoscopy, hence one might expect this to

be the the best point at which to introduce simulator

training. However, there is, overall, a lack of

research on guided simulator training in hospitals.

This study discusses a pilot simulator training

program and presents initial results on the

participation of residents in the program, and on the

279

Silvennoinen M., Antikainen T. and Mecklin J. (2009).

COMPUTER-BASED SIMULATOR TRAINING IN THE HOSPITAL - A Structured Program for Surgical Residents.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 278-283

DOI: 10.5220/0001979502780283

Copyright

c

SciTePress

motivation for training. The paper is organized as

follows: The theoretical grounds for the training are

introduced. A case study and training program in

progress is presented. The aim of the study is set out,

followed by analyses of the initial results. The

results are discussed, with mention of the challenges

that emerged in the study. We present brief

conclusions concerning the training program in its

present state, and make suggestions for the future.

2 THE THEORETICAL BASIS OF

SIMULATOR TRAINING

Here we present the main factors that have

contributed to the creation of simulators, and some

practical ideas for investigating the pedagogical

aspects of simulator training.

2.1 Challenges Regarding the Training

of Skills

It is important to train novices specifically in

laparoscopy, so that they can become automated in

instrument manipulation and in discerning the

transformation of spatial information (Gallagher and

Satava, 2002; Villegas et al., 2003) before entering

the OR. Surgical complications occur most

frequently during the first ten procedures (Jordan et

al., 2000). The technique has certain limitations,

including fixed instrument entry points and limited

degrees of freedom (Berguer et al., 2000). The risks

of the operation are particularly great when one is

working with instruments that are 30 cm in length,

inside the abdominal area, close to fragile organs,

without direct visual contact. The visual-motor tasks

of laparoscopy require excellent hand-eye

coordination. Problems of perceptual motor control

arise when one has to adjust to operating while

watching a two-dimensional monitor image, in a

situation where the camera is held by someone other

than the operating surgeon (Conrad et al., 2006).

One of the main difficulties in learning laparoscopic

skills lies in developing the ability to estimate the

surface roughness of tissues (Brydges et al., 2005).

Overall, it is clear that with this new technique the

challenges in acquiring surgical skills have

increased.

2.2 The Role of Simulators in Training

Simulator training has already given promising

results and has taken on a significant role in teaching

surgical skills, without putting patients at risk

(Cosman et al., 2002; Schjiven et al., 2005; Villegas

et al., 2003). In addition, research has confirmed a

transfer of skills between the simulator and the OR

(Ahlberg et al., 2005 & 2006). For trainees to

achieve the required level of skill, simulator training

should be integrated within the curriculum, and

should rely on the teaching skills of experts

(Ahlberg et al., 2005; Ström et al.,2002). Managing

simulator training has to be an active process, in

order to address the key issue of transferability from

the simulated to the real environment (Kneebone,

2003). The advantages of using simulation have

been listed by Kneebone (2003):

1. Training can be defined by needs of the learner,

not the patient or the teacher.

2. There is permission to fail, and to learn from

mistakes and failures, without risk.

3. The simulator provides objective proofs of

performance and feedback.

The expectations of simulator training have grown at

the same time as simulator technology has evolved.

It has been shown that simulator training improves

OR performance in laparoscopy. Simulators are

regarded as useful tools for introducing equipment

and training technical skills (Poulin et al., 2006).

Simulators could also be used to assess the readiness

of the resident surgeon to proceed to real patient

surgery (Feldman 2004).

3 CASE STUDY: A SIMULATOR

TRAINING PROGRAM FOR

SURGICAL RESIDENTS

The training program was organized in the Central

Hospital of Central Finland. This hospital caters for

a population of almost 280 000. The program forms

part of a multidisciplinary project bringing together

knowledge gained from education, cognitive science

and surgery. The study was performed in a medical

skills learning centre using the interactive Simbionix

Lap Mentor II virtual reality trainer. The training

program was designed to teach laparoscopic skills to

surgical residents, and to further develop existing

skills.

3.1 Study Design – Equipment and

Environment

The medical skills learning centre is an interactive

room containing simulators, cameras and other

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

280

equipment. The idea was to create a peaceful

learning environment where skills could be trained,

whenever actual patient care would allow this. The

Lap Mentor simulator enables the user to interact

with a three-dimensional database in real time, and it

offers games designed particularly for laparoscopic

skills training, plus a realistic image representation

of an organ system. The simulator has real

instrument handles attached to the machine through

robotic instrument ports; these give the sense of

realistic “touch” contact with tissues and organs.

Exercises vary from games and partial operation

exercises to advanced complete operations,

including laparoscopic suturing tasks performed in a

simulated abdomen.

3.2 The Training Program and Data

Collection

The training program for surgical resident education

was launched in March 2008. Prior to resident

instruction, the specialists were given time to

become familiar with the equipment and exercises.

Due to the complexity of the simulator as training

equipment, both the specialists and the resident

surgeons were offered additional help from the

facilitator of the training program. Working

independently or in pairs, the residents were

instructed by a specialist in using the simulator and

going through the exercises. The training program

exercises were selected by a specialist surgeon who

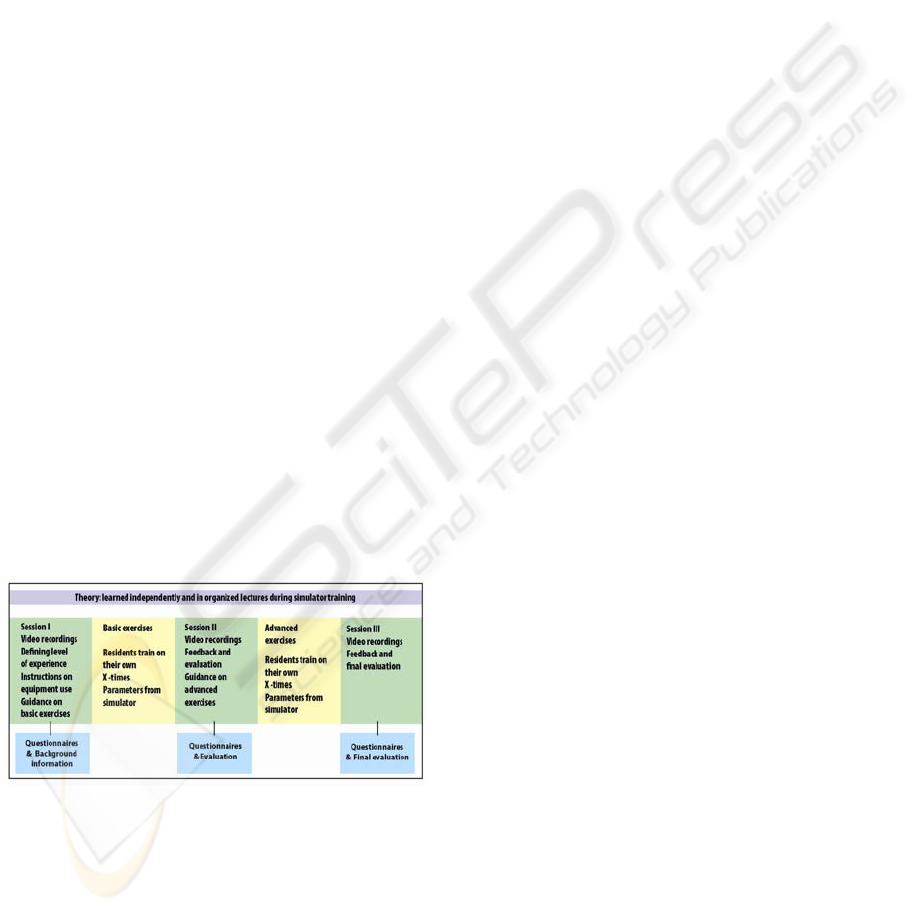

was experienced in simulator training. Figure 1

presents the structure of the simulator training,

including three videotaped training sessions and two

self-training periods.

Figure 1: The training program for surgical residents.

The training program has three instruction and

evaluation sessions in which both the specialist and

the resident surgeon are present. Simulator training

is seen as an element in surgical resident training,

where the overall aim is to integrate the learning of

theory and guided training within both authentic and

simulated environments. During independent

training, all the residents practise the same exercises

until they themselves are satisfied with their

performance.

Data was collected from the first part of the

training program (Session I), and also when the

participants made independent use of the basic skills

trainer (Basic Exercises). The research data consists

of background information on the surgical

specialists and residents, plus information

concerning skills training and exercises performed

with the simulator. This information was collected

via questionnaires. All the simulator exercise

parameters were measured automatically. The

parameters offer detailed information on the

surgeon’s performance, the amount of training, and

errors. The research subjects were all surgical

residents (N=19) who needed to practise their

laparoscopic skills. Three sessions (See Figure 1) in

which both specialist and resident surgeons

participated were videotaped. The video data was

collected with several cameras in order to get

detailed information on the events and actions

during the exercises.

4 THE AIM OF THE STUDY AND

THE RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The study focuses on the first part of the training

program, and the initial results of the residents’

training. We formulated the following research

questions:

1. What were the expectations of the residents at

the start of the training?

2. What is the relationship between motivation

and active participation in the training?

3. What is the relationship between one’s own

self-assessed skills and active participation in

the training?

4. What kind of constraints emerged regarding

participation?

5 RESULTS

The study investigated the main aspects of the

training in its early stage. These aspects include the

expectations and motivation of the participants, and

the resources they allocated to the training program.

An interesting aspect of the research was the self-

evaluated skills of the participants, and the amount

of practice that the participants put in.

COMPUTER-BASED SIMULATOR TRAINING IN THE HOSPITAL - A Structured Program for Surgical Residents

281

5.1 The Expectations and Motivation of

the Residents

The trainees were divided into three groups

according to their level of experience. The beginners

(Group A) had just started their surgical resident

training in the hospital and were at an early stage in

their basic three-year training period. The advanced

trainees (Group B1) had done more than one year of

basic training. The more advanced trainees (Group

B2) had already completed three years basic of

training out of the total of six years resident training.

The expectations (N=17) of the residents

regarding the simulator training were obtained from

the questionnaire data. The less experienced

residents mostly expected to become better

acquainted with laparoscopic techniques and

instrument handling, and to adapt to the new surgical

technique. They also expected to be able to

comprehend a two-dimensional video picture while

they were operating. The more experienced trainees

mostly expected to achieve better dexterity and more

efficient hand-eye coordination. They further

expected to develop a routine in the procedure, and

to learn new procedures. Seventeen out of the total

of eighteen residents who answered agreed that

simulator training would be useful for them.

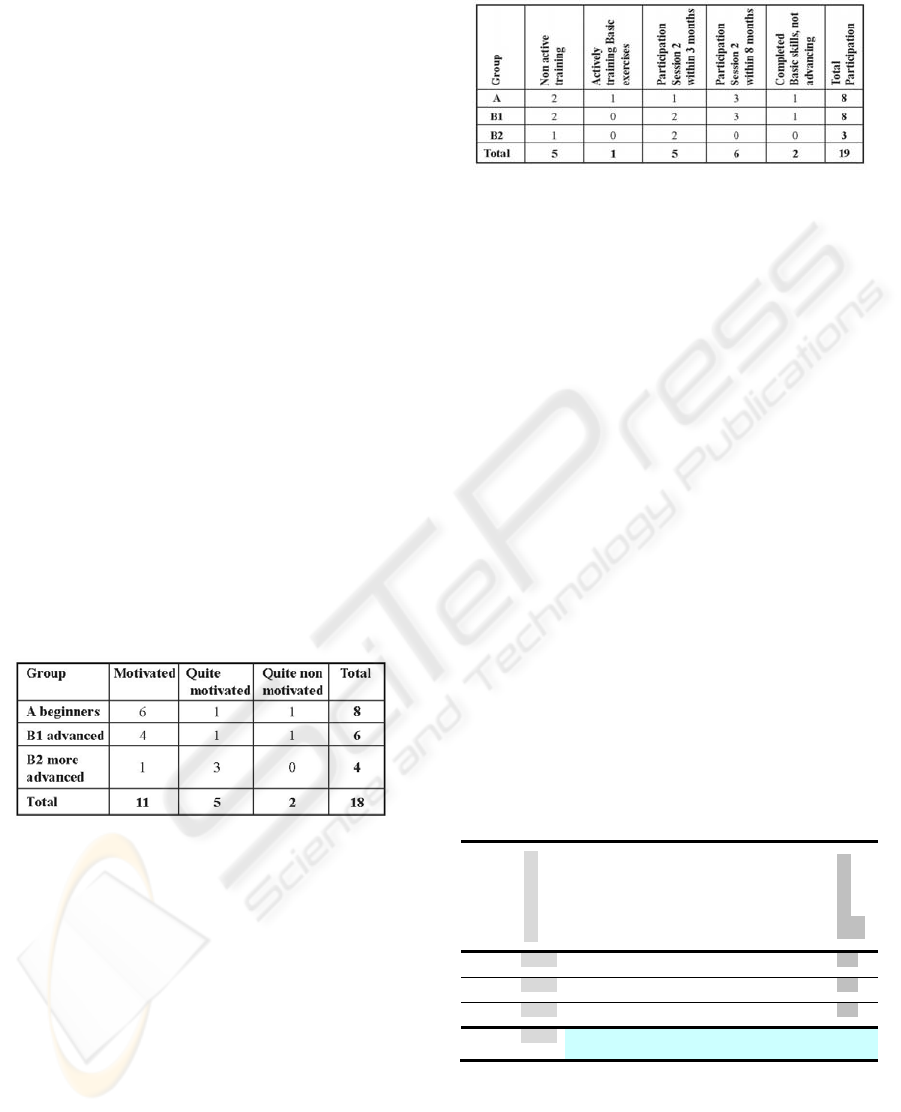

Table 1: Motivation to participate in training.

There were motivated trainees (see Table 1) in each

group. The majority (10/18) of the residents rated as

a demotivating factor future difficulty in finding the

time to practise with the simulator. However, there

was also a high rating (13/18) regarding the

possibility to practise with the simulator outside

normal working hours.

5.2 Levels of Participation and

Constraints

The findings regarding the training program were

based on the researcher’s experiences of the activity

of participants as well as on the questionnaires.

Table 2 summarizes the levels of active

participation.

Non-active training means that the resident

Table 2: Participation.

participated in Session 1, but thereafter did not

engage in independent practice with the simulator.

Participation problems were reported especially by

residents in Groups B1 and B2. The reasons for

cancellations and involvement problems were listed

by the researcher during the training, as follows: (1)

time problems; (2) problems (for both specialists and

residents) in sharing time for guidance sessions; (3)

a lack of motivation for participation among more

experienced residents. The reasons for cancelling

scheduled sessions were usually related to extra

workload situations in the clinic.

5.3 Skill Levels and Time Devoted to

the Training

Residents were given the freedom to train their skills

on the simulator without any upper or minimum

limit on their training times. They were only told to

practise until they felt confident and skilful in

performing the task. There were a total of five

different exercises within the Basic Exercises (see

Table 3). Table 3 shows the mean amount of time

(hours) spent by residents on each exercise. It also

shows the mean level of self-assessed laparoscopy

skill for each group, prior to starting the program.

Table 3: Residents skill level and practising times.

The most active trainees seemed to be the

experienced trainees from group B2. This group also

spent an almost equal amount of time on each

exercise. The residents from group A had less

participation in the more difficult exercises.

Groups

Skill level mean

Mean practice

time Exercise 1

Mean practice

time Exercise 1

Mean practice

time Exercise 1

Mean practice

time Exercise 1

Mean practice

time Exercise 1

Total practice

time

A 0.6 9.5 10.2 7.9 6.0 6.8 31.4

B1 1.6 9.4 6.8 8.0 6.8 7.4 38.4

B2 2.8 8.6 9.5 7.6 7.6 8.3 41.6

Total

mean

1.6 9.2 8.8 7.8 6.8 7.5 8.02

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

282

6 DISCUSSION

Simulator training is intended to aid surgical

residents in the efficient acquisition of good

operating skills. Since resident education tends not

to be very systematically organized in hospitals, new

training methods need to be adopted alongside

traditional ones. In this study simulator training had

a supplementary role within residents’ traditional

work-place learning; hence issues such as

participation and motivation were regarded as

crucial. Training with the simulator was a new and

for the most part unknown issue, for both the

specialist surgeons and the residents. The residents’

expectations were in line with studies mentioned

above, in which it was found that the simulator

seems to provide efficient training in aspects such as

depth perception and instrument control.

The motivation of the trainees was expected to

be lower when their experience level was higher.

Previous studies have recommended that simulator

training should be used at the novice stage of

training, due to anticipated higher motivation at this

stage, prior to the development of “negative

stereotypes” and incorrect practices (Ström et al.,

2002). The presumption was that groups B1 and B2

would be on the whole less motivated. One

unexpected finding in the present study was the

extent to which motivated trainees were present in

every group. There did seem to be more time

available for training at the early stage of residency.

Notwithstanding this, the motivation to train and

participate was not strictly dependent on the level of

the resident. Unmotivated residents did not take part

in the training at all, whereas those who participated

seemed to be committed to the training.

It had been anticipated that the residents would

actively participate in the guided training sessions,

and that they would also be willing to engage in

independent training within the times scheduled for

this. In fact, the levels of active participation of the

trainees emerged as roughly similar for each group,

with no decrease among residents with higher skill

levels. Almost all the participants seemed to be loyal

to the training program, and breaks in the training

were taken only for clearly valid reasons such as

maternity leave or transfer to another workplace.

The skills evaluations were consistent with the

level of experience of the trainees. The residents

evaluated their skills critically. Even if they had

performed operations independently on several

occasions, the skills were evaluated at no more than

4 in a scale of 1-10. The other hypothesis was that

self-assessment of the skill level would correspond

to the time spent on the simulator, and to the number

of training exercises carried out. In fact, what we

found was that the total hours of practice were

highest in group B2, i.e. among those residents who

already had the highest skill level; hence the causal

relationship between skills self-assessment and time

spent on the simulator could not be estimated

directly. One interesting observation concerned the

relationship between the times spent on training and

the difficulty level of the exercises (which increased

from Exercise 1 to Exercise 5). Group A (novices)

did less training on the more challenging tasks than

either group B1 or B2, who spent almost the same

time on all the exercises.

The differences between the times spent on the

tasks in each group could be explained according to

the likelihood that the more difficult tasks would

require more support and guidance in order to

succeed. Without such guidance, the less

experienced residents might well be deterred from

working through the more difficult exercises.

Whatever the reasons, the results do suggest that

self-training – without control of the amount of

training – may lead novice trainees to do merely the

same amount of practice, or even less, than more

experienced trainees. For this reason, the role of the

specialist surgeon (as both evaluator and instructor)

should be taken into account, as an essential element

in the training – even if residents can arrive at a

fairly objective evaluation of their own skills.

Previous studies, too (Kneebone, 2003), have

highlighted the importance of the teaching skills of

senior surgeons as part of simulator training. In our

study, no clear relationship was found between

motivation and active participation, however the

groups that trained most actively seemed to be

slightly more motivated, if we consider that in

Group B2 no participants fell into the “fairly non-

motivated” category.

Surgical training seems to be approaching its

outer limits, bearing in mind that no one knows what

the alternative to traditional education might be.

Over many decades, traditional training has become

incorporated within the everyday routines of

hospitals. Incorporating surgical simulator training

within normal hospital protocols is a demanding and

complex matter. It needs much more basic,

longitudinal research, since the innovations in

training methods that are clearly needed should be

based on real knowledge. There seems little doubt

that simulation has its place as a component in the

training of surgeons, provided that it supports and is

supported by research, technology, clinical practice,

professionalism and education.

COMPUTER-BASED SIMULATOR TRAINING IN THE HOSPITAL - A Structured Program for Surgical Residents

283

7 CONCLUSIONS

The study shows that it is possible to run a guided

and structured simulator training program in a

hospital where the primary task is patient care. The

surgical residents feel positive about simulator

training and wish to intensify and improve their

skills with it. Those who start the training program

seem to remain loyal to it. However, the study

suggests that simulator training needs to be fully

structured – and even mandatory – in order to get all

the residents involved in the training. An effective

and motivating training program necessitates intense

commitment from all the participants, including the

supervisors. Further study is required concerning

problematic features such as time allocation and the

commitment of residents, and the factors involved in

providing adequate supervision and support. The

next logical step would be the analysis of video-

recorded training sessions. The main challenges

seem to involve adapting new methods into hospital

routines, and creating a new learning/teaching

culture within the hospital setting.

REFERENCES

Ahlberg, G., Heikkinen, T., Iselius, L., 2006. Does

training in a virtual reality simulator improve surgical

performance? Surg. Endosc.16;126–129.

Ahlberg, G., Kruuna, O., Leijonmarck, C., Ovaska, J.,

Rosseland, A., Sandbu, R., Strömberg, C., Arvidsson,

D. 2005. Is the learning curve for laparoscopic

fundoplication determined by the teacher or the pupil?

The Am.J Surg. 189; 184-189.

Berguer, R., Forkey, D. L., Smith, W. D. 2000. The effect

of laparoscopic instrument working angle on surgeons'

upper extremity workload. Surg. Endosc. 15; 1027–

1029.

Brydges, R., Carnahan, H., Dubrowski, A. 2005. Surface

exploration using laparoscopic surgical instruments:

The perception of surface roughness. Ergonomics, 48;

874-894.

Cosman, P.H., Cregan, P.C., Martin, C.J., Cartmill, J.A.

2002. Virtual reality simulators: Current status in

acquisition and assessment of surgical skills. ANZ

Journal of Surgery. 72;30-34.

Conrad, J., Shah, A.H., Divino, C.M., Schluender, S.,

Gurland, B., Shlasko, E., Szold, A. 2006. The role of

mental rotation and memory scanning on the

performance of laparoscopic skills. Surg. Endosc.

20;504-510.

Feldman, L. 2004. Using simulators to assess laparoscopic

competence: ready for widespread use? Surgery.

135;28 – 42.

Gallagher, A.G., Satava, R.M. 2002.Virtual reality as a

metric for the assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor

skills. Surg. Endosc. 16;1746-1752.

Jordan, J.A., Gallagher, A.G., McGuigan, J., McClure, N.

2000. Virtual reality training leads to faster adaptation

to the novel psychomotor restrictions encountered by

laparoscopic surgeons. Surg. Endosc. 15;1080-1084.

Kneebone, R. 2003. Simulation in surgical training:

educational issues and practical implications. Med.

Educ. 37:267-277.

Madan, A. K., Frantzides, C. T., Park, W. C., Tebbit, C.

L., Kumari, N. V. A., O Leary, P. J. 2005. Predicting

baseline laparoscopic surgery skills. Surg.

Endosc.19;101–104.

Poulin, E.C., Gagne, J.P., Boushey, R.P. 2006. Advanced

laparoscopic skills acquisition: The case of

laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Clin N Am.

86;987-1004.

Reznick, K. & MacRae, H. 2006. Teaching surgical skills

–Changes in the Wind. NEJM. 355;2664-2669.

Soper, N, J., Brunt, L. M., Kerbl, K. 1994. Laparoscopic

General Surgery. NEJM. 6;409-419.

Schjiven, M.P., Jakimowicz, J.J., Broeders, I.A., Tseng,

L.N. 2005. The Eindhoven laparoscopic

cholecystectomy training course-improving operating

room performance using virtual reality training. Surg.

Endosc.19;1220-1226.

Ström, P., Kjellin, A., Hedman, L., Johnson, E.,

Wredmark, T., Felländer-Tsai, L. 2002. Validation

and learning in the Procedius KSA virtual reality

surgical simulator: Implementing a new safety culture

in medical school. Surg. Endosc.17;227-231.

Villegas, L., Schneider, B.E., Callery, M.P., Jones, D.B.

2003. Laparoscopic skills training. Surg. Endosc. 17;

1879–1888.

CSEDU 2009 - International Conference on Computer Supported Education

284