ON COLLABORATIVE SOFTWARE FOR WEB COMMUNITIES

EVALUATION

A Case study

Laura S. Garc´ıa, Dayane F. Machado, Juliano Duarte, Alexandre I. Direne

Marcos S. Sunye, Marcos A. Castilho, Luis C. E. de Bona and Fabiano Silva

Departament of Computer Science – Universidade Federal do Paran´a – UFPR

Caixa Postal 19.081, Curitiba – PR, Brazil

Keywords:

Collaborative Systems, Evaluation of Interfaces, Check Consistency, Orkut

R

, Web applications.

Abstract:

Collaborative software, and more specifically social software, must provide its users with not only a good

application interface, but also - and more importantly - with easy and direct contact with other users. Within

the field of collaborative software, we chose Orkut

R

as our object of evaluation, particularly in terms of the

following communication tools: communities, messages and scrapbook. The research consisted, initially,

of the evaluation of the abovementioned tools and, secondly, of the assessment of our method itself and its

ability to appraise the inherent features of this kind of software. In the present paper we will introduce and

describe the method upon which we based our assessment. In addition to that, we will justify the choice of

this particular method and discuss the results obtained.

1 INTRODUCTION

Thanks to the technological advances in Computer

Science and Telecommunications, collaborative soft-

ware (or Computer Supported Cooperative Work) en-

ables people to interact. Indeed, the interface environ-

ments based on collaborative software must provide

its users with not only a good application interface,

but also - and more importantly - with easy and direct

contact with other users. (Winogradand Flores, 1987;

Ackerman, 2000; Dourish, 2001; Nicolaci-Da-Costa,

2000; deSouza, 2005; Barbosa and Furtado, 2008),

amongst others, have been emphasising both the so-

cial potentiality of these applications, as well of the

consequent need for designers to become more aware

of the potential social impact of their design choices.

Only then will designers be capable of responsibly

and consciously assisting in the development of this

sort of interface, turning themselves into innovation

agents.

Within the field of collaborative software, we

chose Orkut as our object of evaluation, particularly

in terms of the following communication tools: com-

munities, messages and scrapbook.

Our main objective is, initially, the evaluation of

the abovementioned tools and, secondly, the evalua-

tion of our method itself and its ability to appraise the

inherent features of this kind of software.

In the present paper we will introduce and de-

scribe the method upon which we based our assess-

ment. In addition to that, we will justify the choice

of this particular method and discuss the results ob-

tained. Finally, we will sketch our final conclusions

and point towards future work.

2 METHOD AND

JUSTIFICATION

The method chosen for the present research was Con-

sistency Inspection (CI).

The choice of a rather theoretical method can be

justified as follows. Methods based upon theory,

amongst which CI is an example (Polson et al., 1992;

Wharton et al., 1994), enable not only the analysis of

the interface characteristics (as does Heuristic Analy-

sis - HA), but also - and more importantly - the identi-

fication of task-related problems. Moreover, one such

identification does not take individual procedures into

account, but rather oversees each procedurewithin the

patterns and logic that pervade the entire application.

61

S. García L., F. Machado D., Duar te J., I. Direne A., S. Sunye M., A. Castilho M., C. E. de Bona L. and Silva F. (2009).

ON COLLABORATIVE SOFTWARE FOR WEB COMMUNITIES EVALUATION - A Case study.

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Human-Computer Interaction, pages 61-65

DOI: 10.5220/0001987500610065

Copyright

c

SciTePress

We opted for Consistency Inspection because we see

consistency as one of the paramount characteristics

of any user-interface environment. After all, a lack of

consistency compromises the quality of the interface

regardless of the kind of application.

3 EVALUATION PROCESS

In the present section we will describe the method we

used in the evaluation process of the environment in

question.

(Rocha and Baranauskas, 2003, page 169), de-

scribe Consistency Inspection as follows: ”The eval-

uator checks the consistency within a software inter-

face in terms of terminology, colours, layout, formats,

as well as other interface components. The training

and help materials available online are also evalu-

ated”.

Based upon the general characterization described

above, we added more precision to our evaluation

method by incorporating the analogy introduced by

(Payne and Green, 1987) for interface languages,

which in turn refersto the threelevels in which natural

languages can be analysed, namely semantic, syntac-

tic and lexical levels. Both the semantic and the syn-

tactic level address the inherent properties of the lan-

guage itself. In terms of evaluation, these two levels

are responsible for determining whether the language

fulfils the requirementsthe languageitself establishes.

These requirements basically refer to whether the lan-

guage is regular enough to enable users to correctly

foresee the effects and purposes of certain design fea-

tures within the environment. The semantic level is

subdivided into expressivecompleteness and properly

called consistency. While the former concerns the se-

mantic power, the latter refers to the regularity and ac-

curacy of the language itself, i.e. to whether the very

same icons or labels trigger identical actions through-

out the application, be it in different contexts or in as-

sociation with different objects. Finally, the syntactic

level concerns the composition rules of the system’s

demands, and the lexical level refers to the proximity

between the most basic languagecomponents(such as

button labels, menu options, icons, amongst others)

and the users’ expectations. These components are

appraised according to their inherent concept, their

external appearance and their interpretation expecta-

tion (i.e. the meaning attributed to them by the de-

signer), thus pointing towards the continuity between

the application and the users’ model of the system.

For our research, we haveexpandedthe list of con-

sistency levels so as to incorporate an additional con-

tinuity axis between the design model and the users’

model (Norman and Draper, 1986), namely the dis-

cursive or structural level. This fourth level concerns

the conformity between display (organization) of the

application’s tools and tasks and the users’ expec-

tation about what the application will provide - i.e.

which useful tasks, for instance, will solve their prob-

lems in the real world. In other words, the idea is that

the structure and potential of the tools must meet the

users’ expectations about the application.

In order to expand the evaluation method even fur-

ther, we propose the extension of the analogy to the

social realm. This way, we can take advantage of the

great contributions made by the Speech Acts (Searle,

1969; Searle, 1979) and the Cooperativity Principles

(Grice, 1975), which in turn refer to the speaker’s un-

derlying intentions in human communication and to

the cooperative utterances, respectively. These contri-

butions to collaborative applications and technologi-

cal mediation were used by Winograd in the system

”The Coordinator” (Flores et al., 1988) and later by

(deSouza, 2005) within their theoreticaldiscussion on

the relationship between Pragmatics, Speech Acts and

Culture.

According to (Searle, 1979), there are five kinds

of Speech Acts, as follows: Assertive, Directive,

Declarative, Commissive and Expressive. Assertive

Speech Acts state the truthfulness of what is being ut-

tered; the main purpose of Directive Speech Acts is

to get the listener to fulfil a task; through Declara-

tive Speech Acts there is a change in the state of the

sender’s and the receiver’s world, as well as in the

context of the utterance; Commissive Speech Acts

establish the speaker’s commitment to a future action;

finally, Expressive SpeechActs drawthe listener’s at-

tention towards the speaker’s psychological state or

attitude. Even though each different kind of Speech

Acts has its own expressive features, they may be ex-

pressed indirectly through sentences not necessarily

in the typical linguistic form.

Expressions concerning the rules and terms of use

of a certain system, be it through imperatives or in-

directly, may be perceived as Directive Speech Acts.

Commissive Speech Acts, on the other hand, can be

applied to the system’s commitment to resolving situ-

ations of abuse and ill use.

The Cooperativity Maxims devised by (Grice,

1975) seem particularly relevant to hypothetical con-

texts because they portray the basic principles of

”good communication” amongst human beings, prin-

ciples which are necessary in the transposition to

technology-mediated communication. In this con-

text, Grice came up with four maxims, namely Quan-

tity, Quality, Relevance and Manner. The Quantity

maxim refers to the fact that participants must make

their contributions to the conversation as informative

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

62

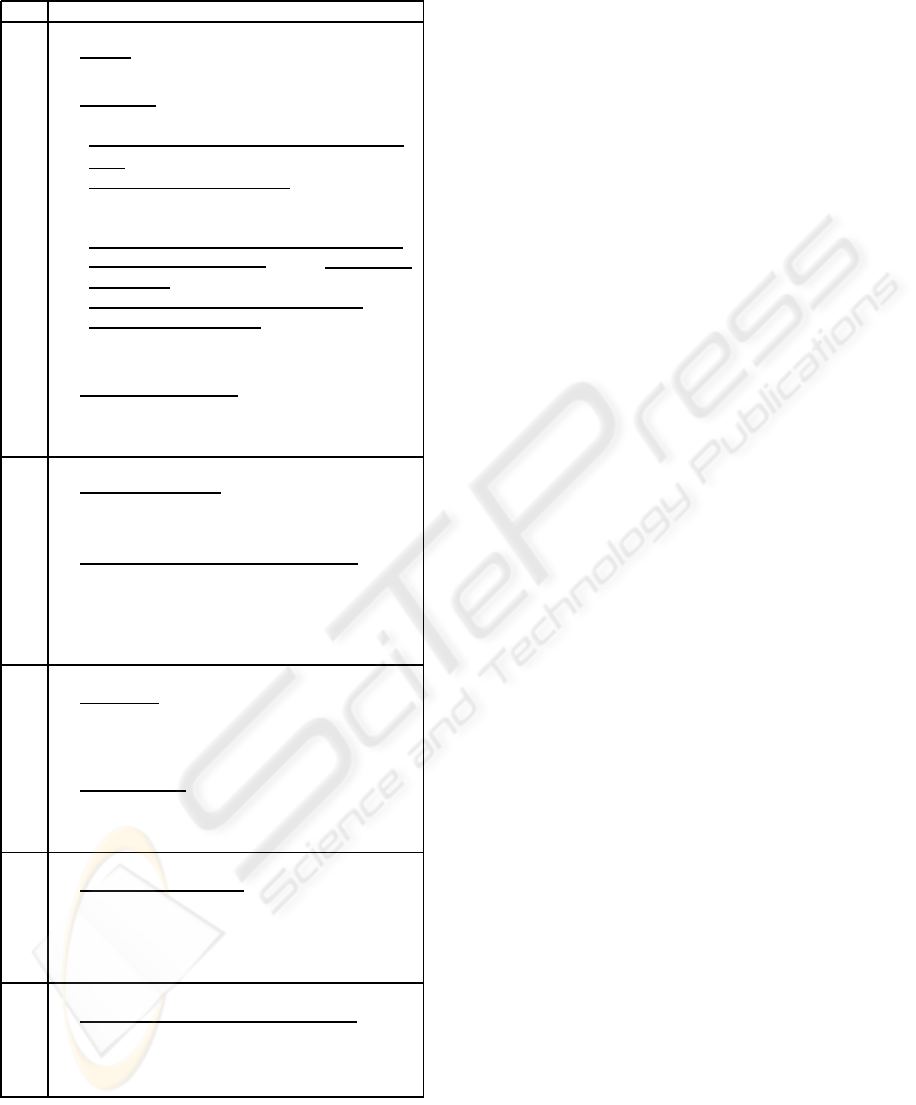

Table 1: Tool proposed for Consistency Inspection - CI.

Level Aspects

PRAGMATIC

1. Intention When a user accesses a collaborative system, it

must reveal the application’s intention;

2. Terms of Use The system must also make its Terms of

Use available. It must make the following items clear:

the extent to which the users’ contributions can be made

public – which ranges from private to universal; the

level of formality required/accepted – including the pos-

sibility of using both figures of speech, such as irony, and

bad language, comprising thus ethical issues in general;

the extent to which the system can ensure the adherence

to these terms of use, as well as punish possible

transgressions. Additionally, the system must reveal

possible hierarchical relationships amongst users, such as

possible autonomy restrictions amongst members of the

same community. This item concerns Grice’s ”Manner”

maxim;

3. ”Pragmatic Expressiveness” The language must be expres-

sive enough to reveal specific moods and personality traits

through emoticons, for instance.

DISCURSIV

4. The set of tasks available in the application must be com-

patible with theset of tasks expected by users in analogous

situations in the real world;

5. The organization of menus and content in general must be

natural for the user; in other words, the sequence of ac-

tions required for carrying out a task must make sense for

the user, which demands that the content itself must be

clearly presented.

SEMANTIC

6. Completeness particularly in terms of the regularity of in-

herently communicative action pairs, among which are

question and answer, request and help, and statement and

comment;

7. Actual consistency the same labels/icons must trigger the

very same actions, be it in different moments of the inter-

action or in correlation with different objects.

SYNTACTIC

8. Rules for action specificationeven in graphic environments,

taking widgets as language elements.

LEXICAL

9. Labels/icons semantically and articulatorily close to the

users’ expectations about the object and its display.

as necessary (neither more nor less). The Quality

maxim asserts that participantsshould only contribute

with pieces of information whose truthfulness they

cannot ensure (that includes avoiding hesitating infor-

mation and lies). The Relevance maxim urges that

participants contribute with information which is rel-

evant to the current conversation. Last but not least,

the Manner maxim asserts that participants must ex-

press their ideas clearly, avoiding ambiguity.

Regarding collaborative software, we can make

use of the quality maxim to complement the direc-

tive Speech Acts. In this sense, quality may help to

uncover both those aspects over which the system has

control, as well as those aspects over which it has lim-

ited control, such as the content of the participants’

contributions - in terms of the text’s inherent charac-

teristics, comprising Grice’s four maxims.

Based upon these premises we devised our assess-

ment tool, described in Table 1.

4 RESULTS

In the present section, we will present the results of

the application of Consistency Inspection to Orkut’s

communities, scrapbooks and messages Table 2, in

addition to an analysis of the results obtained.

According to the methodology described in the

present paper, the process of Consistency Inspection

has proven to be useful for identifying consistency

flaws on lexical, syntactic and semantic levels, hence

providing relevant insight on how to improve the en-

vironment.

Having expanded the analogy introduced by

(Payne and Green, 1987) within the context of Task-

Action Grammars (TAGs) so as to appraise additional

levels of the interactive language, and having drawn

inspiration from the Speech Acts (Searle, 1969) and

from the Cooperative Principle (Grice, 1975) so as to

specify the items to be evaluated pragmatically, the

process of Consistency Inspection described here was

partially successful in terms of grasping the commu-

nicative abilities of the environment in question, par-

ticularly regardingthe system’s explicitness of the so-

cial potential of the application, as well as of the un-

derlying rules of mediated communication.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORKS

Even though the evaluation method applied to this

particular case study has proven to be fruitful - espe-

cially when one takes the initial objectives into con-

sideration -, a few issues within the investigation pro-

cess must be pointed out.

ON COLLABORATIVE SOFTWARE FOR WEB COMMUNITIES EVALUATION - A Case study

63

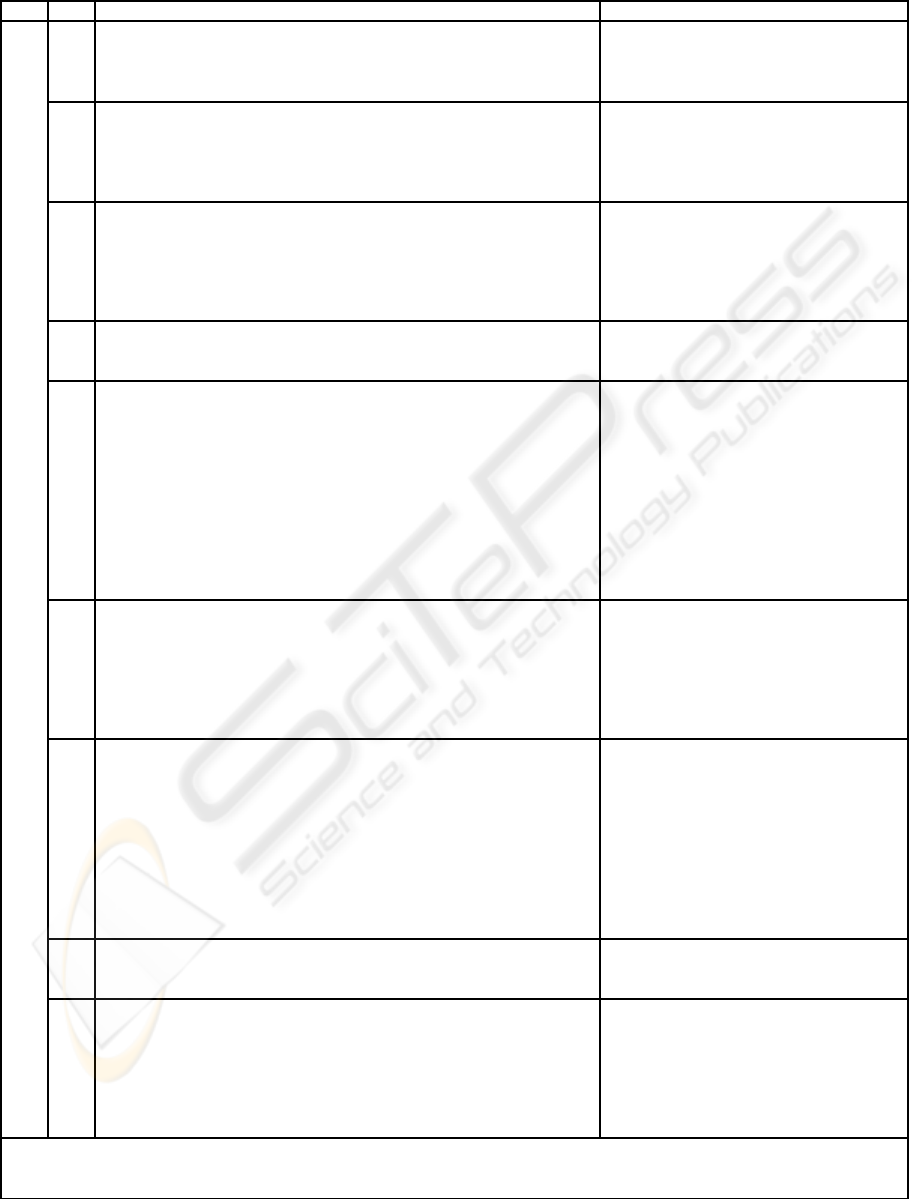

Table 2: Consistency Inspection in Communities, Scrapbooks and Messages.

Hypothetical cause of the problem (Re)design alternative to solve it

ASPECTS

1 There is no visible description of the environment’s objectives. In the initialisation

screen there is a description of some of the benefits with which the environment pro-

vides its users, and after login there is a link ”about Orkut”, which offers more details.

Insert a clearly visible link entitled ”Learn more

about Orkut”. Display concise descriptions of each

of the many tasks and tools offered by the environ-

ment.

2 The environment does not mention which kinds of objects are allowed, nor does it

reveal the appropriate level of formality required. Privacy terms are explicitly stated

and their fulfilment is assured. The environment exempts itself from any responsibility

concerning its content, claiming that any cases of misbehaviourshall be fully and solely

attributed to the users.

Describe the kinds of objects that are allowed,

along with the register that should be used in mes-

sages.

3 The application enables the use of emoticons within the scrapbook environment, but

not in other contexts in which they would also be pertinent. However, because the

messages, scrapbook posts and other means of communication make use of the users’

natural languages (including freedom of speech and the use of abbreviations, usually

not accepted in the standard language), one can express different moods and personality

traits.

Enable the access to emoticons in all contexts in

which they are relevant.

4 Both the top menu bar and the left-hand menu (for online users) refer to objects (scrap-

book, messages, communities, photos, videos, amongst others) and not to the main

actions that the system offers.

Display menu options (including all possible ac-

tions) associatedto the object over which the cursor

is placed (contextual help).

5 The organization of the menus into successive submenus is relatively satisfactory, de-

spite the fact that there are problems. The context line underneath the title of the

main window is not displayed in all situations where it would be pertinent. Within

the community environment, when the user is the manager of the community, the op-

tion ”Delete community” is hidden below the option ”Edit profile”, which may cause

the user to think it does not exist. In most analogous environments, this option is placed

amongst the others in the left-hand menu. Similarly, within the ”Friends” environment

the option ”Add friend” is the first option of the left-hand menu, whereas the action

”Remove friend” is ”hidden” somewhere within the ”More” link. Within the scrap-

book and message environments, items are displayed in list fashion, whereas the topics

are displayed in line.

Display context line in all pertinent situations. Sub-

stitute top bar labels by the same labels preceded by

the first person singular possessive adjective ”my”.

Shift the option ”Remove friend” onto the same po-

sition as the option ”Add friend”.

6 Even though users can make use of emoticons within the message environment, they

cannot use them in other situations where they would be pertinent (though we have al-

ready pointed it out in item 3 above, under Pragmatic Expressiveness) Although users

can visualise the text to be posted within scrapbook and topic environments, they can-

not see it within the message environment. Within the forms under ”Edit profile”,

standard icons (i.e. question marks) indicate where help is provided by the application.

However, within other environments help is not provided at all.

7 Though relatively consistent, the system does present significant semantic consistency

flaws. Different labels lead to the same action. ”Delete” and ”Remove”, for instance,

cause the object to which they are associated to disappear. In addition to that, the

recycle bin icon and the ”x” and ”-”symbols trigger the same action. On the other

hand, some of the same labels have different meanings. The ”Messages” designated by

a closed envelope, for example, may refer either to the users’ unread messages (when

located underneath the welcome message), or to the users’ inbox (when located in the

left-hand menu of online users). Actions related to messages can be accessed through

a combo-box, whereas the two possible actions related to scrapbooks are displayed

through command buttons.

8 We detected no concrete problems. Despite that, designs that favour objects over ac-

tions seem to make it more difficult for user to carry out actions. This hypothesis must

be studied further.

9 We detected a few significant lexical inconsistencies. There is a series of arbitrary

icons within the environment, as follows: testimonials are designated by several icons,

including a sun, a medal and a flower; the adjective ”trusty” is represented by a smile,

and ”cool”, a slang word, either by what seem to be ice cubes or by two juxtaposed

leaves; the icon that leads to the profile of a certain community consists of three little

circles; the label ”search this forum” is confusing, as well as the icon designating the

action ”join this community”.

Substitute arbitrary icons by icons with zero se-

mantic and articulatory distance. Substitute the la-

bel ”Search this forum” simply ”Search”. Substi-

tute the chain icon by an icon displaying another

ring being added to a chain.

Key: 1 - Intention; 2 - Terms of Use; 3 - “Pragmatic Expressiveness”; 4 - Set of tasks available at the beginning of the session;

5 - Organisation of the subsequent menus and/or content; 6 - Completeness; 7 - Actual consistency; 8 - Rules for action specification;

9 - Labels/icons semantically and articulatorily close to users’ expectations.

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

64

Lack of consistency concerning the traditional lan-

guage levels (i.e. semantic, syntactic and lexical) of

the interface language of most computational systems

may compromise the quality of collaborative soft-

ware (or the quality of any software, for that mat-

ter). The method of Consistency Inspection provides

a quite satisfactory evaluation of these traditional lev-

els. However, in terms of detecting semantic, syntac-

tic and lexical flaws, the effectiveness of the method

seems to be hindered by the fact that it is rather diffi-

cult to carry out the assessment systemically and ex-

haustively. One such difficulty derives from two dif-

ferent issues. The first one concernsthe complexityof

the application, which in turn makes use of abstract

concepts inherent to intellectual artefacts (deSouza,

2005). Collaborative software may be perceived this

way (i.e. trivially and as constructions) because they

mainly comprise aspects of human communication, a

process whose very foundation lies in a linguistic sys-

tem, in other words, a socio-technological variant of

the users’ mother tongue. The second issue or hin-

drance refers to the withdrawn treatment (from the

users’ point of view) both of the concept of object

(the ”friends”), and of the concept of instance (the se-

lected friend).

In terms of the evaluation of the differential fea-

tures of collaborative software, the performance of

Consistency Inspection is satisfactory since it can as-

sociate social actions to system actions. One such as-

sociation, however, takes place only in terms of the

environment’smeta-communication (deSouza,2005),

in relation to both the design intentions and the code

of conduct that people generally follow.

We strongly believe that we must develop this re-

search further so as to improvethe input instrument to

Consistency Inspection and hence provide a broader

evaluation of the differentials of collaborative soft-

ware. The proposal described here represents the first

step towards this long-term objective.

Moreover, we are confident that technological en-

vironments designed for social purposes still lack

more substantial research on the use of the application

itself (Suchman, 2006). Indeed, most user-interface

evaluation methods(or at least the onedescribedhere)

tend to fail to detect flaws of this type. The methods

derived from Sociology emerge as promising alterna-

tives in the context of the evaluation of both the users’

social behaviour (and not only the system’s communi-

cability in relation to the objectives and action limits)

within the environment, as well of the impact of the

environment on the real world, beyond the applica-

tion.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, M. S. (2000). The intellectual challenge of

cscw: The gap between social requirements and tech-

nical feasibility. Human-Computer Interaction v.15.

n.2.

Barbosa, C. and Furtado, E. (2008). Competio de avaliao

de sistema.

deSouza, C. S. (2005). The Semiotic Engineering of

Human-Computer Interaction (Acting with Technol-

ogy). The MIT Press.

Dourish, P. (2001). Where the action is. MIT Press, Cam-

bridge, MA.

Flores, F., Graves, M., Hartfield, B., and Winograd, T.

(1988). Computer systems and the design of organi-

zational interaction. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst., 6(2):153–

172.

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. Academic,

New York.

Nicolaci-Da-Costa, A. M. (2000). A tecnologia da intimi-

dade. Anais do III Workshop sobre Fatores Humanos

em Sistemas e Computao, IHC 2000.

Norman, D. A. and Draper, S. W. (1986). User Cen-

tered System Design; New Perspectives on Human-

Computer Interaction. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,

Inc., Mahwah, NJ, USA.

Payne, S. J. and Green, T. R. G. (1987). Task-action gram-

mars: A model of the mental representation of task

languages. SIGCHI Bull., 19(1):73.

Polson, P. G., Lewis, C., Rieman, J., and Wharton, C.

(1992). Cognitive walkthroughs: a method for theory-

based evaluation of user interfaces. Int. J. Man-Mach.

Stud., 36(5):741–773.

Rocha, H. V. and Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2003). De-

sign e Avaliao de Interfaces Humano-Computador.

NIED/UNICAMP, Campinas, SP.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech Acts. Cambridge, UK, Cam-

bridge University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1979). Expression and Meaning. Cambridge,

UK, Cambridge University Press.

Suchman, L. A. (2006). Human-Machine Reconfigurations:

Plans and Situated Actions. Cambridge University

Press, New York, NY, USA.

Wharton, C., Rieman, J., Lewis, C., and Polson, P. (1994).

The cognitive walkthrough method: a practitioner’s

guide. pages 105–140.

Winograd, T. and Flores, F. (1987). Understanding Com-

puters and Cognition: A New Foundation for De-

sign. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.,

Boston, MA, USA.

ON COLLABORATIVE SOFTWARE FOR WEB COMMUNITIES EVALUATION - A Case study

65