Knowledge Management in a Multinational Context:

Aligning Nature of Knowledge and Technology

Cataldo Dino Ruta and Ubaldo Macchitella

Department of Management, Bocconi University

Via Roentgen 1, 20136 Milan, Italy

Abstract. Aim of this paper is to show the importance of understanding the

nature of both the technology and knowledge when promoting knowledge

sharing through knowledge management (KM) portals. This paper investigate

knowledge sharing and the “fit” between the nature of knowledge to be shared

and the nature of the technological tools that are used. Technology intended as

technical instrument could result in an empty box, and knowledge management

initiatives could not be effective and lead to a sustainable competitive

advantage. By means of an in-depth case study of a major consulting firm, the

study discusses and answer the research question. Results show that knowledge

areas with high level of codifiability can be effectively shared by using low

collaborativity and low multimodality tools. Knowledge areas with a high level

of epistemic complexity can be effectively shared by using high collaborativity

and high multimodality tools. Knowledge areas with a high level of task

dependence can be effectively shared by using low collaborativity and

intermediate multimodality tools.

1 Introduction

In the last decade knowledge management (KM) received much attention from both

practitioners and theorists. Interest in knowledge management issues was significantly

boosted by the rapid evolution of information systems [15]. The new features

introduced by innovative technological tools, like the possibility to share information

on real-time and get in touch with people around the world, has led many companies

to imagine a new world of leveraged knowledge [12].

Knowledge management systems are very often embedded in more

comprehensive technological infrastructures such as Human Resource (HR) portals

[2] and represent an invaluable instrument to foster the intellectual capital of an

organization.The goal of this paper is to investigate the relation between the nature of

knowledge and technology in order to have an effective KM system.

Ruta C. and Macchitella U. (2009).

Knowledge Management in a Multinational Context: Aligning Nature of Knowledge and Technology.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Human Resource Information Systems, pages 129-138

DOI: 10.5220/0002211001290138

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 Theory

2.1 The Relevance of Knowledge Management for Sustainable Competitive

Advantage

Organizational knowledge, and therefore knowledge management, are key in

sustaining competitive advantage over time. Grant [7] develops a knowledge-based

theory of organizations. He affirms that knowledge is the most important strategic

resource for a firm. It resides in specialized form among individual organizational

members and the essence of organizations is its ability to integrate the specialized

knowledge of individuals.

However, even if originating from different fields and perspectives, these

contributions present some aspects in common. In first place, they underline the

relevance of knowledge for competitive advantage. With more or less emphasis, they

refer to knowledge management mechanisms as a key element in developing

capabilities that allow a sustainable, high performance. A second common feature

across these contributions is the strict linked between knowledge and technologies. In

some contributions technology is seen as a technical support for knowledge transfer

that favours the construction of organizational capabilities [11], [5], [18], [14].

According to other authors [7], [13], [1] technology not only concurs to the process of

developing capabilities but also embodies knowledge and capabilities in itself.

Summarizing, from the analysis of the literature emerges that: 1) knowledge and

its management are issues relevant to the construction of organizational capabilities

and that 2) the nature of both knowledge and technology should be taken into

consideration. Therefore, in the next section we present a model linking knowledge

and technology that can be applied to knowledge management projects.

2.2 The Effectiveness of HR Portals: The Match between Technology and

Knowledge

HR portals are vehicles through which HR information and applications can be

channelled effectively and efficiently [2]. HR portals have technical characteristics

that support employees contribution and participation in knowledge management

systems: employees’ personalization through information profiling, relevance of

information and customized single user interface. HR portals present several tools that

support knowledge sharing, from document repositories to more interactive tools like

forums, chat or blogs, the so called KM portals. In order to unfold their beneficial

effects on knowledge management, employees should adopt these instruments and use

the in their everyday working life. The adoption and use of technologies from the

users is an issue that has been extensively investigated within the Information System

Management literature. An established theoretical framework is the one of task-

technology Fit [4]. According to this model, a “fit” between the nature of technology

and the task to be executed should exist in order to perform the task effectively. We

apply the same idea to the knowledge management context. Considering knowledge

sharing as the “task” that should be carried out, we propose a model of “knowledge-

technology fit”, linking the nature of knowledge to be shared to the characteristics of

130

technological tools used to share it. We investigate this “fit” according to some

dimensions derived from the literature that we present in next sections. We’ll consider

the case of a world-wide consulting group. By the analysis of this case study we can

test our theoretical framework and formulate our research propositions.

Knowledge Dimensions. Knowledge has been already measured and described

according to different dimension in previous studies. Zander and Kogut [17]define

codifiability, teachability, system dependence and product observability as the four

charachterisitcs influencing the speed of transfer of organizational capabilities and,

consequently, determining the capability to imitate internal managerial practices. In

particular, these authors find out that the level of codifiability and the easiness of

teachability have a significant influence on the transfer process speed. Grandori [6]

points out three main characteristics: tacitness, computational complexity and

epistemic complexity. These knowledge dimensions influence the choice of

organization and inter-organization coordination mechanisms. Hansen [8] focuses on

codifiability and system dependence as the two main characteristics that can help to

explain difficulties in the transfer of a practice. Knowledge with a higher level of

codifiability and a lower degree of dependence will be easy to transfer. In our study,

the phemomenon of knowledge sharing, and particualrly the decision process in the

choice of KM tools, is presentend from a contingency perspective. Referring to

previous studies, we indicate four main dimensions of a knowledge area as

influencing its degree of transferability: codifiability, epistemic complexity, task

dependence and knowledge comeptitiveness.

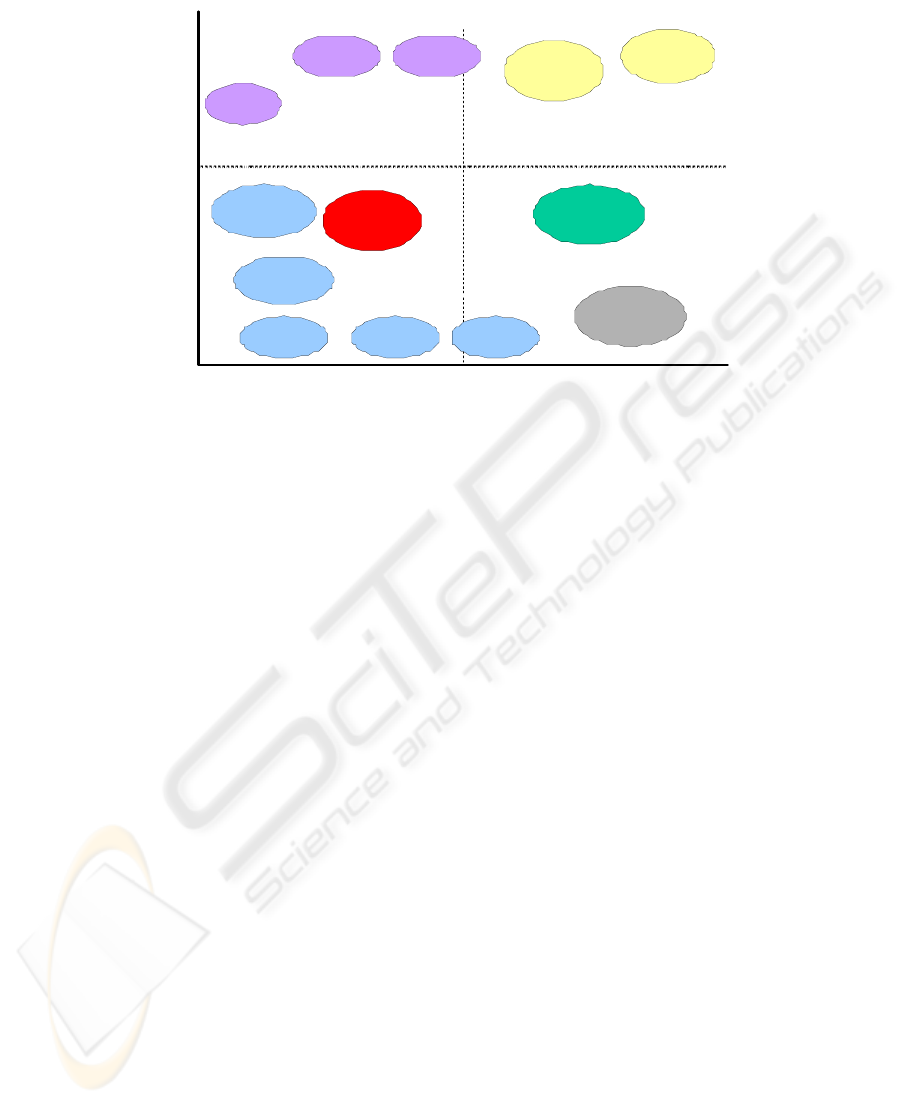

Technologies for Knowledge Management. Drawing on the classifications of

technology suggested by the theories referring to task-technology fit, we now propose

a model for the analysis of technologies for knowledge management based on two

main dimensions. The first dimension of our model is collaborativity. Technologies

for KM enable people geographically dispersed to work jointly and to exchange

knowledge by direct interaction. Typically, these tools make possible the

collaboration among people working on the same task, or support experiences of

distribute learning [16].

The concept of “collaborativity” is also at the heart of Fulk et al. [3] studies, that

define the distinction between communality and connectivity. Tools oriented to

collaboration are the ones that present a higher level of connectivity, intended as the

ability of the tool to create connections between people.

The second characteristic by which we classify instruments for knowledge

management is multimodality. We define multimedia as “the seamless integration of

two or more media” by supporting two or more channels like text, graphic, sound and

motion, expressed in an increasingly complex order [9].

The following table presents the synthesis of the most used KM applications

(email, audio-conference, video-conference, groupware, online meeting spaces, online

discussion spaces, personal directories, text databases, intelligent data operating layer,

audio databases, video databases, multimedia simulations, multimedia encyclopaedia)

with specific levels of collaborativity and multimodality.

131

On - li n e

discussion

spaces

HIGHHIGHLOWLOW

MULTIMODALITY

COLLABORATIVITY

L

O

W

L

O

W

HIGHHIGH

Human-to-human

H u m a n- t o- n on - h um a n

On-line

me et ing sp ac es

Groupware

A u di o- co n f er en ce Video-conference

E-mail

M u lt im ed ia

simulations

Intelligent data

operatinglayer

“Mu ltim edia

en cycl op a ed ia”

Personal

Directories

Text Database A u di o D at ab ase Video Database

I

IIIII

IV

Fig. 1. A classification of instruments for Knowledge Management.

Therefore, based on these theories, we expect a relation between the nature of the

knowledge that is shared within the company and the KM tools hosted by the HR

portals.

We investigate this relation in Martinelli consulting (fantasy name). In the next

section we present the methods we used to carry out our investigation. Further, we

presents the results of our case study and discuss them in the light of the theoretical

framework we used.

3 Methods

Data and information on the KM applications of experts and users were collected,

selecting the most common applications and defining a script for each of them, in

order to have clear data on functionalities and multiple possible usages. 5 KM experts

and 5 users were asked to read these scripts and to grade the KM applications on

collaborativity and multimodality based on their characteristics from 0 to 9. Questions

about collaborativity were oriented to assess if the KM application is able to connect

and involve a great number of people, human-to-human, from one-to-one to one-to-

many. Compared to a low level of collaborativity when the KM application facilitates

interaction between human and non-human actors (i.e. databases). Questions bout

multimodality were oriented to assess if the KM application offers two or more media

(text, graphics, audio, animation, etc) in an integrated way for communicating among

people. Finally, the 10 values for each application were averaged, asking them to

decide the final value in cases of fragmented numbers (i.e. 6.5)

Knowledge dimensions could represent an important predictor in the choice of

tools (in terms of collaborativity and multimodality) for knowledge sharing. The

132

model we defined has been examinated by the analysis of a case study in order to

further investigate the ideas suggested by the theory. The research method we used is

the one of the case study as suggested by Yin [19]. This method has been selected as a

consequence of the exploratory purpose of our paper. Our analysis has been

conducted in the Italian office of Martinelli Consultants, one of the leading groups

worldwide in organization and technology consulting.

We used three techniques for data collection, so respecting the principle of

triangulation: participant-observation, qualitative interview and document analysis.

Participant-observation took place for a period of more than six months, during

which one of the authors joined the Italy Knowledge Management team of Martinelli

Consulting. In this period the researcher has been equiparated to the other members of

the team, carrying out the same activities, having the same working instruments than

his colleagues (desk, laptop, corporate e-mail, telephone), sharing the same working

spaces, and participating to all the events of the team life (meetings, work-in-

progress, training courses, presentations and so on). This helped to avoid the

“observer paradox” described by Labov [10], making the behavior of the observed

people not reactive.

A significant part of the data collection has been developed by carrying out

qualitative semi-structured interviews we made to 52 consultants in Martinelli. The

choice of the people and the groups to be interviewed was made following a

systematic approach in order to have a good representation of the entire Martinelli.

With the help of the Head of Knowledge Management Office we selected eight

groups working on the typical Martinelli business, and we intervewed people

covering all the organizational positions and different roles within the workgroups.

The contents of our interviews were related first of all to the composition of the

workgroup, to better interpret the information we obtained. A second section of the

interview protocol referred to the five or six macro tasks that the workgroup carried

out. In the same section was asked to specify the knowledge areas used to execute the

tasks that had been indicated. In the third section of the interview protocol we

investigated the four characteristics of codifiability, epistemic complexity, task

dependence and organizational competitiveness of the knowledge areas indicated by

the respondents, using the following scale: 1-3 (low), 4-6 (intermediate), 7-9 (high).

The scales were taken from Zander and Kogut’s [17] work on practices and their

transfer, and were adapted to the concept of knowledge areas that were critical in this

study. While the “codificability” construct was quite well-defined and applicable to

our context, some adaptations were necessary to measure “complexity.” We

considered “teachability” and “output observability” as part of a more expanded

knowledge complexity construct. Indeed, in this study the ease of defining cause-and-

effect relationships, and the variety of problems and solutions, are also part of the

complexity measure. Questions related to codifiability: Existing work manuals and

operating procedures describe precisely what people working in this knowledge area

actually do; most of the solutions to the problems related to this knowledge area are

described in written manuals; the outputs related to this knowledge area are well

documented. Questions related to epistemic complexity: a competitor can easily learn

how we produce outputs related to this knowledge area by analysing carefully all the

related resources used and produced for these outputs; the quality of the output

depends more on the judgment of the experts than on well defined rules; within the

practice of this knowledge area, a given action has a known outcome; the problems

133

related to this knowledge area are always different. It is not convenient to collect and

store them.

Questions related to task dependence: indicate the degree to which each

knowledge area is needed to complete each task (previously identified in the group

project). Questions related to organizational competitiveness: this knowledge area is

crucial for the success of the firm; we cannot allow that this knowledge is accessed by

external people or competitors.

The last section of the protocol was about the use of technology tools for the

working activities and the use of the corporate portal. In particular, we examined

which kinds of knowledge area were retrieved and contributed from the portal and

which ones, instead, had the project leader as an important link to external sources.

We attempted to map the habits in the acquisition and contribution of information, in

terms of “problems” and “solutions” related to a particular knowledge area.

The technique of document analysis has been adopted with the aim of

investigating the use of KM tools that consultants have at their disposal. By

classifying the documents that are on the Martinelli KM Portal it has been possible to

understand how technology supports the sharing of the different knowledge areas in

Martinelli. To operate this classification we performed a document analysis on a

sample of the documents contained in Martinelli KM portal. We analyzed 2850

documents on a total of about 8000 documents referred to the Martinelli Italian

Region. These documents have been extracted from the two most representative

sections of Martinelli KM Portal: the Global Container (fantasy name) and the

Management Section (fantasy name). The Global Container is the Martinelli general

knowledge repository, while the Management Sections is a best practice database. Of

these document we counted the frequency of appearance.

4 Findings

4.1 Knowledge Areas in use in Martinelli Consulting

From the analysis of the knowledge areas emerged by the interviews, it has been

possible to define three macro-classes of knowledge areas (KA).

A first class of knowledge area is represented by managerial knowledge areas.

This macro-class is made up of all the group management methodologies, the ability

to organize one’s work in coordination with other team members, the rules for the

interaction with other colleagues, the ability to use all the tools required by the

workgroup activities and so on.

A second macro-category of knowledge areas is represented by technological

knowledge. Seven out of the eight workgroups we examined heavily relied on this

kind of knowledge. Technological knowledge typically consists of programming

languages (ADA, C++,…), operating system source-codes, web design architectures,

technological platforms and so on.

Finally, the third knowledge macro-class coming out from the interviews is the

one of process/market knowledge. Process knowledge is intended as all the

knowledge areas that must be managed in order to implement the service to the client.

These knowledge areas can be related to the specific nature of the client or to the

134

particular kind of job delivered to it. For example, an ERP implementation will

require different knowledge areas than an Application Maintenance service.

Market knowledge, instead, is simply the information related to the specific sector

in which the client operates.

The level of organizational competitiveness for the three macro-classes was the

same. All the respondents, in fact, considered equally important the different

knowledge areas and said that not particular tensions generated when sharing any

kind of knowledge.

Far less homogeneous is the situation for codifiability. Managerial knowledge

areas, in fact, showed a high level of codifiability; technological knowledge, instead,

showed a low level of codifiability. An intermediate level of codifiability was

obtained by market/process knowledge. From the aspect of epistemic complexity, we

noticed a low level for managerial knowledge areas, an high level for technological

knowledge area and an intermediate level for market/process knowledge areas.

Finally, task dependence resulted intermediate for managerial and technological

knowledge areas, while it was very high for market/process knowledge. The results of

this assessment are reported in table 2.

Table 1. Assessment of knowledge areas.

Codifiability Epistemic complexity Task Dependence

Managerial K.A.

HIGH LOW INTERMEDIATE

Technological K.A.

LOW HIGH INTERMEDIATE

Market/process K.A.

INTERMEDIATE INTERMEDIATE HIGH

4.2 KM Tools in Martinelli and their Utilization

We analysed the main tools of the HR Portal available to the consultants for

knowledge sharing. These tools can be conducted to the general type of instruments

that we defined as repositories, that support knowledge sharing following a

distributive logic.

The document analysis conducted on the Global Container and Management

Section of Martinelli KM Portal shows the documents that more frequently appear are

the ones related to market/process knowledge areas (64%), followed by the the ones

related to managerial knowledge areas (35%). Document pertaining technological

matters, are instead totally absent, even in the three technological Boxes.

A similar composition of documents has been found in the Management Section:

also in this repository the mainly represented macro-class of knowledge is

market/process (81%), followed by managerial knowledge (19%). Documents related

to technological knowledge areas do not appear.

From the analysis of the Global Container and Management Section emerges the

complete absence of technological knowledge. This could sound quite strange in a

company that makes technology consulting its core business. This situation is

confirmed by the words of the project leader of group number five: “whenever I have

a problem related to technology I’m sure I cannot rely on the portal! Probably,

programming languages and other technological stuff are too specific to be usefully

135

shared on the portal; problems are always different and it’s not convenient to store

them. So, I usually take the telephone and make a call to a colleague expert on that

domain of knowledge”.

5 Findings

From the analysis of the Martinelli case we obtain the following findings. In first

place, we notice how the tools available on the Martinelli KM Portal can be

reconducted to only one of the four categories of KM tools we defined in our model:

the ones with low collaborativity and low multimodality. On the base of our study,

besides, we also found that, of the three knowledge areas identified, only two are

effectively shared by using the these tools. Technological knowledge, in fact, is not

available at all on Martinelli KM Portal. This suggests the presence of a relation

between knowledge dimensions and the characteristics of the technological tool used

to transfer knowledge. As a consequence of the existence of this relation, some

knowledge areas can be shared by a particular means, while others cannot. Drawing

on this we can deepen the general model of task-technology fit. In particular, within

the relation between knowledge and technology, we can observe the following

relations.

5.1 The Relation between Codifiability and KM Tools

The presence on the Martinelli KM Portal of managerial and market/process

knowledge areas reveals how a high level of codifiability requires the use of a low

collaborativity and low multimodality tools, such as the Global Container and the

Management Section.

Proposition 1

: Knowledge areas with a high level of codifiability can be effectively

shared by using low collaborativity and low multimodality tools

.

5.2 The Relation between Epistemic Complexity and KM Tools

The complete absence of technological knowledge areas on Martinelli KM Portal

shows how knowledge area. with a high level of epistemic complexity cannot be

shared by using low collaborativity and low multimodality KM tools.

On the contrary, tools with a high level of collaborativity and high level of

multimodality are indicated for this kind of knowledge.

Proposition 2

: Knowledge areas with a high level of episteimc complexity can be

effectively shared by using high collaborativity and high multimodality tools.

136

5.3 The Relation between Task Dependence and KM Tools

From the analysis developed in Martinelli Consulting we found out as knowledge

areas with a high level of task dependence can effectively be shared by using tools

with a low level of collaborativity and a low level of multimodality. Market/process

knowledge area were widely present on Martinelli KM Portal. This shows that the

“repository” logic is suitable when dealing with knowledge with a high level of task

dependence.

Proposition 3

: Knowledge areas with a high level of task dependence can be

effectively shared by using low collaborativity and intermediate multimodality tools.

6 Conclusions

Our experience shows that knowledge management initiatives can fail if they are not

included in the wider context of organizational capabilities. As Teece et al. [15] warn,

the ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to

address rapidly changing environments is a matter of dynamic capabilities.

Knowledge management tools and techniques are only a partial aspect of these

mechanisms and cannot assure by themselves a sustained competitive advantage.

Our results indicate that the implementation of technologies for KM should be

accompanied by a deep understanding of the nature of the knowledge that is going to

be shared and of technology used to share it. Our paper, however, presents some

points that need to be developed. Further research could be addressed to carefully

define which is the “dominant” dimension within a knowledge area. In other words,

the three characteristics of codifiability, epistemic complexity and task dependence

could be present in the same knowledge area. It would be critical, therefore, to define

which one, of this three knowledge dimensions, has the major influence in the

decision process underlying the selection of the appropriate tool for knowledge

sharing.

Another point to be addressed by further research, could be testing these

propositions in other contexts, in order to reach a god level of statistical

generalization. What we primarily aimed in this paper has been, instead, a sound level

of theoretical generalization, consistently with the qualitative techniques we used.

References

1. Capron L. and W. Mitchell. How elephants learn new tricks: internal and external

capability sourcing in the European telecommunication industry. Academy of management

best conference paper 204 BPS: M5. (2004).

2. Firestone, J. M.. Enterprise information portals and knowledge management. Boston:

Butterworth- Heinemann. (2003).

3. Fulk, J., A. J. Flanagin, M. E. Kalman, P.R. Monge and T. Ryan. Connective and

commnunal public goods in interactive comunication systems. Communication Theory,

pp.60-87. (1996).

137

4. Goodhue, D.L. and R.L. Thompson. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS

Quarterly, June. (1995).

5. Gold A., A. Malhotra and A. Segars. Knowledge management, an organizational

capabilities perspective. Journal of management information systems 18:1. (2001).

6. Grandori, A. Organization Networks and Knowledge Networks. Paper presented at 16

th

Egos Colloquium, Helsinki. (1999).

7. Grant R.. Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments : organizational capability

as knowledge integration. Organization science 7:4. (1996).

8. Hansen, M. T.. The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge

across organization subunits. Administration Science Quarterly 44 (1) 82-111. (1999).

9. Heller, R.S. and C.D. Martin,. A Media taxonomy. IEEE MultiMedia, 2, 4, 36-45. (1995).

10. Labov, W. Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. (1972).

11. Lei D., Hitt M. and Bettis R. Dynamic core competences through meta-learning and

strategic context. Journal of management 22:4. (1996).

12. McDermott R. Why information technology inspired but cannot deliver knowledge

management. California Management Review 41:40. (1999).

13. Ranft A. and M. Lord. Acquiring new technologies and capabilities: a grounded model of

acquisition implementation. Organization science 13:4. (2002).

14. Sher P. and V. Lee. Information technology as a facilitator for enhancing dynamic

capabilities through knowledge management. Information and management 41, pagg. 933-

945. (2004).

15. Teece, D.J., G. Pisano and A. Shuen. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management.

Strategic Management Journal 18: 509-553. (1997).

16. Zack, M. Knowledge management and collaboration technologies. White Paper, The Lotus

Institute, Lotus Development Corporation, July. (1996).

17. Zander, U. & Kogut, B. Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of

organizational capabilities: an empirical test, Organization Science, 6: 76-92. (1995)

18. Zollo M. and S. Winter. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities.

Organization science 13:3. (2002).

19. Yin, R. K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Vol. 5. Applied Social Research

Methods, ed. Leonard Bickman. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. (1984).

138