A TAXONOMY SCHEMA FOR WEB 2.0

AND MOBILE 2.0 APPLICATIONS

Marcelo Cortimiglia, Filippo Renga and Andrea Rangone

Department of Management, Economics & Industrial Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Via Colombo 40, Milan, Italy

Keywords: Web 2.0, Mobile 2.0, Application taxonomy schema.

Abstract: In recent times, much attention has been given to the Web 2.0 phenomenon and related notions such as

Social Computing, Social Media and User-Generated Media. However, whenever Web 2.0 is mentioned, it

is usually surrounded by vague and ambiguous concepts and definitions, mostly a complex mixture of

technical and business aspects. This paper proposes to shed a light in such a fuzzy environment by

proposing a taxonomy schema for Web 2.0 applications using as main categorizing criteria the type and

characteristics of interaction permitted or facilitated by the applications. The proposed taxonomy schema is

then extended to the Mobile 2.0 scenario by discussing the possible implications of mobility applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent times, a number of trends in information

and communications technology led to the

emergence of a phenomenon commonly referred to

as Web 2.0. A consensus on how to precisely name

and define the phenomenon is still far away – and

given the numerous aspects it encompasses, maybe

it will never be achieved. Even so, these terms are

commonly employed as catch-all expressions for a

myriad of interactive applications that support and

facilitate collaboration, community formation,

content production and sharing by users, and social

interaction. Examples include blogs, forums, content

aggregators, social networks, and content

communities (Constantinides & Fountain, 2008).

In addition to the lack of consensus on definition,

there is also much confusion about the underlying

characteristics of the Web 2.0 phenomenon and how

to categorize its applications. Indeed, much of the

published research on the topic has to do with

specific and single practical applications, without a

great concern for the larger picture or for how

applications relate to each other.

The situation is even more chaotic when

considering the extension of the Web 2.0

phenomenon to the wireless technological domain.

Not only there are less articulated efforts to define

and understand Mobile 2.0, but also systematic

research about its applications is scarce.

In light of these considerations, the objective of

this paper is to propose a taxonomy schema for Web

and Mobile Social Computing applications that uses

as main categorizing construct the type of interaction

permitted of facilitated by the applications.

2 WEB 2.0

Recent years witnessed an undoubted paradigmatic

shift in the Web: from a linear structure of one-to-

many content production, distribution and

consumption to a participatory structure based on

open, inclusive, collaborative and customizable

applications that allow users to collectively create,

share, evaluate and use digital content. This change

was enabled by the wide availability of broadband

Internet connectivity, including continuous

connectivity through wireless channels, and the

increase on processing power and memory capacity

in personal computing devices, including mobile

handsets (Parameswaran & Whinston, 2006).

The result of this paradigmatic shift is a complex

and multi-faceted phenomenon, frequently called

Web 2.0 (O'Reilly, 2005; Oberhelman, 2007; Levy,

2009), but also known as social computing

(Parameswaran & Whinston, 2006), Social Media

(Constantinides & Fountain, 2008) or even User-

Generated Media (Shao, 2009). The multi-faceted

nature of this phenomenon become evident when

one considers these varied nomenclatures as efforts

to highlight the multiple aspects of the phenomenon

69

Cortimiglia M., Renga F. and Rangone A. (2009).

A TAXONOMY SCHEMA FOR WEB 2.0 AND MOBILE 2.0 APPLICATIONS.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 69-76

DOI: 10.5220/0002234200690076

Copyright

c

SciTePress

at hand. Similarly, the fact that many sources define

Web 2.0 by examples of applications (Oberhelman,

2007; Cox, 2008) is evidence of its complexity.

2.1 Technological Approach

A frequent common ground in attempts to

understand Web 2.0 and its impacts is O'Reilly's

(2005) set of principles. Firstly, O'Reilley (2005)

proclaims that the web should be viewed as a

platform to develop services. He states that the web

should be understood simply as a channel for the

services, as content become central in giving

services a competitive edge.

Services, on the other hand, should be designed

so they can be openly mixed and assembled, in a

culture of constant experimentation. This is reflected

also in the “permanent beta” motto, meaning

constant and continuous improvement and dynamic

change (based above all on user feedback). Still

regarding service design, O'Reilley (2005) posits

that it should focus on delivering a rich user

experience, a clear reference to user empowerment.

Furthermore, services have to be designed in a

way that their performance – and consequent value –

improve automatically the more it is used,

capitalizing on data access and network effect. This

requires, understandably, intense and active user

participation in the form of a collective intelligence,

and the emphasis of individual, unsegmented

consumers described by Anderson (2006).

At the same time, this means Web 2.0 users are

considered content producers themselves. This is the

reasoning behind the emergence of interest in User-

Generated Content (UGC), that is, content publicly

accessible, resulting from a reasonable amount of

creative effort and generated outside the traditional

and professional practices (Wunsch-Vincent &

Vickery, 2007).

Following O'Reilley's (2005) line of reasoning, it

is natural to view applications as the fundamental

constructs of Web 2.0. This is, after all, a very

practical solution for the problem of defining such a

complex and multi-faceted phenomenon, with so

many real-world implications. Indeed, many works

on Web 2.0 involve the study of single applications

(Barsky & Purdon, 2006a, 2006b; Eijkman, 2008;

Fu et al., 2008; Parker, 2008; Scale, 2008; Wyld,

2008; Hearn et al., 2009).

According to Shao (2009), two important

common characteristics of Web 2.0 applications

make them specially appealing. Firstly, they are easy

to use, having great usability, requiring little input

and generating significant gratification. Secondly,

they allow users to be in control by being highly

customizable and allowing interaction without time

and space constraints.

For the purposes of this paper, a comprehensive

but non exhaustive list of Web 2.0 technologies

drawn from Anderson (2007), Levy (2007), and

Parameswaran & Whinston (2006) includes: blogs,

wikis, RSS, social bookmarking, content tagging,

social networks, content sharing, syndication and/or

aggregation, and thematic communities.

2.2 Social Approach

As Hendler & Golbeck (2007) note, O'Reilley's

(2005) view of Web 2.0 is strongly biased towards

technology, putting services and UGC on its core.

Another approach would be to consider the social

aspect of the phenomenon (Parameswaran &

Whinston, 2006; Constantinides & Fountain, 2007;

Shao, 2009), a notion whose roots can be traced

back to views about the Web itself: “more a social

creation than a technical one” (Berners-Lee, 1999, p.

123). This supports the observation that the Web 2.0

movement is not based on fundamentally innovative

technologies, but on the innovative way user

interaction is allowed by these technologies

(Constantinides & Fountain, 2007).

In this sense, the fundamental construct of the

Web 2.0 become the users themselves and, more

importantly, the relationships and interactions

among them. As Barsky & Purdon (2006a) put it:

“Web 1.0 was almost all about commerce, Web 2.0

is almost all about people”.

Nevertheless, these two approaches should not

be seen as contrasting. Indeed, a common feature of

both is the strong and decisive focus on interaction.

After all, as Shao (2009) pointed out, the

participatory culture characteristic of Web 2.0 means

that users do not only consume content, they directly

interact with and enrich it.

On the other hand, users directly interact with

other users in a much larger scale than before, to the

point of constructing and maintaining social

relationships and, in the process, coming up with

new and innovative content.

3 WEB 2.0 APPLICATIONS

TAXONOMY SCHEMA

If the defining concept for Web 2.0 is interaction, it

is then only natural to use it as a categorizing

construct for a taxonomy schema involving Web 2.0

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

70

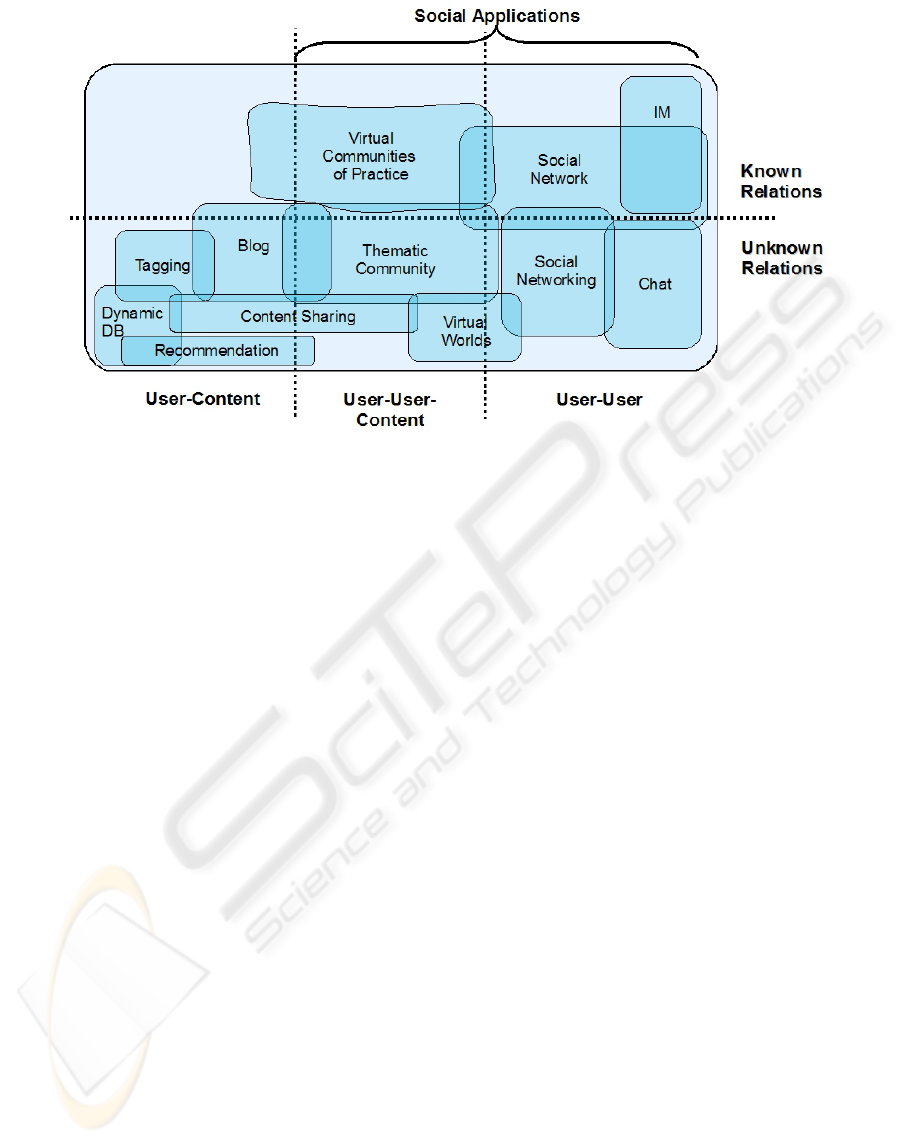

Figure 1: Visual representation of the proposed taxonomy schema.

applications. Interaction is a wide concept, though,

so it is necessary to specify which aspects of

interaction are relevant for classification purposes.

The first one is the main interaction focus.

Evidently, the centre of the interaction is always the

user. In the Web 2.0 paradigm, user interactions can

be focused on digital content (user-content), other

users (user-user) or content and other users

simultaneously (user-user-content).

User-content interaction can be distinguished

between passive and active. While the former means

basically passive consumption of pre-generated

content (usually from professional or semi-

professional sources), the latter involves direct

involvement with the so-called dynamic content, i.e.,

content created and/or augmented by users. Active

user-content interaction is a fundamental

characteristic of Web 2.0 applications.

Similarly, user-user interaction can be further

distinguished by interaction continuity and user

familiarity. Interaction between users can be

expected to be continuous and sustained or

instantaneous and transient. While the former is a

precondition to maintain social relationships, the

latter is characteristic of practical communication

interactions. Moreover, users involved in interaction

can previously know each other or not, determining

the type of user familiarity and, of course, the

purposes and characteristics of the interaction itself.

The proposed taxonomy schema for Web 2.0

applications uses as its main categorizing criteria the

type and characteristics of interaction permitted or

facilitated by the applications.

Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the

proposed taxonomy schema. The horizontal axis

shows the three types of interaction focus considered

(user-content, user-user-content, and user-user),

while the vertical axis shows the two possibilities of

user familiarity. The fact that application types

overlap in the visual representation is an indication

that real-world applications usually mix and share

characteristics of more than one application type, as

prescribed by O'Reilley's (2005) Web 2.0 principles.

3.1 Dynamic Content Applications

Dynamic Content Applications (DCA) permit or

facilitate interaction between user and content.

However, contrary to the traditional web user-

content interaction paradigm where users passively

consumed content pre-generated, Web 2.0 content

applications are focused on the active aspect of the

interaction and the dynamic aspect of content. In this

approach, users are more than content consumers, as

they actively interact with content in order to

transform and enrich it.

However, using DCA, users usually transform

and enrich content in relative autonomy and

isolation. The resulting dynamic content is then

consequence of indirect interaction by many

individual users, not a direct collaborative effort.

This is not to say that there can be no user-user

direct interaction, only that it is much less

emphasized than user-content interaction, and tends

to be mostly indirect, like rating a news piece of

commenting on someone else's blog post.

A TAXONOMY SCHEMA FOR WEB 2.0 AND MOBILE 2.0 APPLICATIONS

71

According to the proposed taxonomy schema,

the following applications can be classified as DCA:

tagging applications (also known as social

bookmarking, such as Digg and Delicious); dynamic

databases (Google Maps, housingmaps.com and

iGoggle, for instance); recommendation systems

(like Amazon and Netflix); content aggregation and

sharing (such as YouTube and Flickr), and blogs

(e.g., Blogger or LiveJournal).

Interaction focus centered on dynamic content

instead of social interactions is evident in Cox's

(2008) analysis of Flickr, one of the most

representative and popular DCA. He points out that

although Flickr has elements of social network site,

such as profiling and group membership, “in general

Flickr is not very interactive – not very social”.

3.2 Social Content Applications

Social Content Applications (SCA) differ from DCA

in the sense that users do not actively interact only

with dynamic content, but also with each other

during the process of content transformation and

enrichment. Thus, the focus here is on the social

content, i.e., content collectively produced, shared

and/or transformed by users' interactions. Regarding

interaction continuity, a defining characteristic of

SCA is that they may allow for sustained user-user

interactions. This means that some level of

community formation is supported. However, the

main objective of these communities of users is not

to foster social relationships, but to promote

collaborative production, use and sharing of content.

Thus, sustained interactions are not a required

characteristic of these applications.

In fact, SCA can be further detailed considering

user familiarity and interaction continuity.

Groupware (including Virtual Communities of

Practice and Virtual Learning Systems) involve

mostly known users and sustained interactions,

usually in work or learning-related contexts, while

Thematic Communities centered on specific topics

of interest involve mostly unknown users and spot

interactions. Finally, a specific type of SCA emerged

in the form of Virtual Worlds, the most famous of

these being Second Life, but also including

massively multiplayer online games such as the

popular World of Warcraft (Ducheneaut & Yee,

2009). In Virtual Worlds, the main interaction focus

can be said to be evenly distributed between social

content (the interactive world, in the case of Second

Live, the game itself, in the case of World of

Warcraft) and social interactions, as usually there

are present features that allow for sustained user-

user interaction such as profiles and list of friends.

3.3 Communication Applications

These are applications focused on user-user transient

interactions. In this category are included e-mail,

forums, bulletin boards, newsgroups, mailing lists,

chat and instant private messaging, which were

already fully developed well before Web 2.0 drivers

prompted the surge of user-user interaction (Herring,

2002). Now, these tools can be found incorporated

in or complementing other Web 2.0 application

types, or even used as is to improve communication

efficiency (Hearn et al., 2009; Zimmerman & Bar-

Ilan, 2009). A few specific communication

technologies however, are typical of the Web 2.0

phenomenon, such as RSS feeds (Wusteman, 2004)

and public messages exchanged by members of

social network sites (Thelwall, 2009).

Specific Communication Applications are

appropriate according to different types of user

familiarity. While instant private messaging is

mostly used for keeping in contact with known

relations, chat rooms are commonly used by users

that do not know each other beforehand. Similarly,

Social Communication Applications could be further

categorized according to aspects like synchronicity,

persistence of transcript and participation structure

(Herring, 2007), but it does not add value to the

proposed taxonomy schema.

3.4 Social Network Applications

In a certain way, these are the most complete Web 2.0

application type, as they usually integrate many

functionalities present in other types of applications.

The main focus of Social Network Applications

(SNA) is social interactions, i.e., user-user sustained

interactions, allowing for – even encouraging – the

formation and maintenance of persistent relationships.

Boyd & Ellison (2008) defined SNA as “web-

based services that allow individuals to (1) construct

a public or semi-public profile within a bounded

system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom

they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse

their list of connections and those made by others

within the system.”

Specifically regarding the social connections

represented in the list of linked users displayed in

profiles, Boyd & Ellison (2008) argue that a

distinctive characteristic of SNA is the fact that they

are not aimed primarily at building new relationships

(what would be understood as “networking”), but at

representing and allowing communication within

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

72

their existing social networks – usually based on

offline connections (Subrahmanyam et al., 2008).

While most SNA provide options for

communication among users (personal and public

messaging tools are almost standard nowadays),

privacy, access control and profile visibility settings

are among the technical characteristics that vary the

most among SNA.

3.5 Social Networking Applications

Applications in this category are very similar to SNA,

as their main focus is also user-user sustained

interactions. They also share many of SNA's defining

characteristics, such as profiles (usually highly

detailed) and list of connections (when present,

normally closed). The defining difference is that these

applications are used to initiate social interactions

with previously unknown users. In other words, they

are focused on networking, (Boyd & Ellison, 2008).

The most representative Social Networking

Application is the dating website (Bishop, 2009), and

its distinct features is user search based on profile

matching.

4 MOBILE 2.0

The Web 2.0 phenomenon attracted significant

interest from the scientific community in the last few

years, but the same can not be said about Mobile 2.0.

Indeed, it is currently more an industry-related

hyped buzzword than an actual well established

construct.

Among the few attempts to analyse the Mobile

2.0 concept, some authors state that Mobile 2.0 is

the next generation of mobile data services (Jaokar

& Fish, 2006). A more prosaic – and perhaps

practical – definition would be the extension of Web

2.0 services and applications to the mobile and

wireless technological domain (Burns et al., 2007;

Griswold, 2007). In this way, most of the

considerations made for the Web 2.0 phenomenon

are valid for Mobile 2.0.

For instance, it is interesting to note that

technical and social approaches to define Web 2.0

are in a certain way replicated when Mobile 2.0 is

considered. That is the case for Lugano's (2007)

definition of Mobile Social Software (MoSoSo):

“mobile applications whose scope is to support

social interaction among interconnected

individuals”, a software typically open and focused

on the user.

Similarly, Jeon & Lee (2008) listed a series of

technical trends considered by them as distinct traits

of Mobile 2.0 concept. These include full browsing

capabilities (implying search and advertising-based

business models and flat data rate connections) on

smartphones and other powerful computing mobile

devices, standard and Mobile AJAX-enabled

dynamic content, mixed and assembled open

applications, navigation enhanced with RFID and

barcode, and emergence of mobile UGC and mobile

social networks. Notably, these trends resemble

various drivers and characteristics of Web 2.0

already discussed.

However, as Holmquist (2007) and Lugano

(2007) point out, Mobile 2.0 applications can not be

a simple transposition of their Web 2.0 equivalents;

they must exploit the unique characteristics of

mobility and mobile devices.

Clarke (2001) mentions four mobile value

proposition attributes: ubiquity, convenience,

localization and personalization. By ubiquity, he

indicates the fact that most mobile devices are

constantly connected to the network, resulting in

availability at virtually “any time and everywhere”.

Similarly, convenience means that mobile users are

not restricted by usual time and place constraints,

while the localization attribute indicates the ability

to easily locate and identify the mobile user. Finally,

by personalization Clarke (2001) means the fact that

mobile devices are extremely personal, usually

directly linked to only one user, with his own

preferences and desires for self-expression.

It is clear that these mobile value proposition

attributes are aligned with many of the Web 2.0

principles. Localization and personalization, for

instance, can be seen as potentially enhancing the user

empowerment effect, one of the most innovative

aspects of the Web 2.0 phenomenon. Furthermore, the

ample diffusion of mobile devices with multimedia

capability can intensify the user tendency to create,

diffuse and share (Perey, 2008).

5 MOBILE 2.0 APPLICATIONS

TAXONOMY SCHEMA

As it was for the Web 2.0 paradigm, interaction can

be seen as one of the fundamental characteristics of

the Mobile 2.0 phenomenon. Thus, it remains the

categorizing construct for the Web 2.0 applications'

taxonomy schema translation into mobility. Picking

up on the interaction focus considered in section 3,

Clarke's (2001) mobile value propositions will be

A TAXONOMY SCHEMA FOR WEB 2.0 AND MOBILE 2.0 APPLICATIONS

73

analysed in order to draw insights for Mobile 2.0.

First of all, it must be considered that the

cellphone is an user-user interaction device by

nature, be it through traditional voice and video

calls, text messaging or instant messaging. These

user-user interactions can be further enhanced by

mutual awareness provided by localization systems.

Regarding user-content interaction, Lugano

(2007) mentions that Mobile 2.0 applications tend to

be heavily customizable. Indeed, this Web 2.0

tendency is intensified by the personalization

attribute of mobility mentioned by Clarke (2001):

mobile devices are extremely personal, and so must

be the applications used through them. Adding to

that is the fact that many Mobile 2.0 applications

may integrate personal information about user

identity and address book, rendering these

applications extremely personal.

Also the limitations of mobile devices should be

considered when examining interaction in the

Mobile 2.0 context. Screens and keyboards' small

size and the pattern of use of mobile devices, which

imply frequent interruptions, can render difficult the

tasks of reading and inputting text (Holmquist, 2007;

Lugano, 2007). As mentioned by Perey (2008),

navigation behaviour in mobile devices is therefore

concentrated more on images and keywords and less

on browsing, writing and reading. At the same time,

limited processing power and battery life are usually

mentioned as additional device limitations that may

impair user enjoyment, specially when dealing with

multimedia content (Holmquist, 2007).

Overall, considering the effects of mobility and

mobile device attributes on interaction focus, one

may argue that Mobile 2.0 applications tend to

emphasize more user-content and user-user-content

interactions than user-user interactions (Lugano,

2007). The formers take the form of direct

consumption and sharing of multimedia content,

taking advantage of mobile devices' multimedia

capture capabilities and usually conducted through

dedicated keyboard commands. On the other hand,

user-user interaction is based on mobile device's

natural communication features and can be enhanced

by localization and awareness capabilities, although

text reading and inputting may be somewhat limited.

5.1 Social Networking Applications

Analogue to Web 2.0 DCA, these applications focus

on user-content interaction. However, given the

limitations on content creating and editing related to

mobile device characteristics, mostly are not pure

Mobile 2.0, but hybrid mobile-web applications.

Representative subcategories of Mobile DCA are

Mobile Blogging and Mobile Content Sharing. Both

benefit from multimedia capture capabilities of

contemporary mobile devices. For instance, most

web-based blog management systems and content

sharing websites can be accessed by mobile

applications that allows users to upload multimedia

content and even to create and edit blog posts.

Additionally, DCA that make use of aggregated

data indirectly collected from mobile users, such as

Recommendation Systems and Dynamic Databases,

benefit from the integration of data related to user

location and identity. Google Latitude, for instance,

is an example of such an hybrid mobile-web DCA.

5.2 Mobile Social Content

These are the equivalent of Web 2.0 SCA, the main

example being the Mobile Thematic Communities.

Characteristic features of Mobile Social Content

Applications include the user-content interaction

focus, usually with the objective of exchanging

knowledge or informative content related to a

specific shared thematic subject. User-user

interactions are mediated by the content itself in the

form of content-related comments, ratings or public

messaging/forum, as user profiles and list of

connections, which are typical user-user interaction

enabling features, are present only in limited form.

However, this type of application tends to provide

good usability when content upload and

consumption is involved.

Groupware and Virtual Worlds are not yet

diffuse on the mobile environment, mainly because

of device limitations: computing power and screen

size (which hinder mostly Virtual World-type

applications) and keyboard and screen size (mostly

affecting Groupware and other collaborative

technologies ). However, there are success cases of

integrated use of mobile and web-based systems for

mobile workforce and collaborative learning systems

(Holmquist, 2007; Griswold, 2007).

5.3 Mobile Communication

Just like their Web 2.0 counterparts, these

applications focus on permitting and facilitating

user-user interactions, specially the immediate type,

both between previous known and unknown users.

Most one-to-one tools, such as e-mail and private

messaging, are aimed at keeping in touch with

known relations, while one-to-many tools, like chat

and public messaging, are mainly used for

communicating with new or unknown relations.

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

74

These mobile applications are mostly adaptations

of existing web-based communications platforms for

the mobile technological domain. For example, there

are mobile applications that permit the user to access

a traditional web-based e-mail or private messaging

client, modified to cope with device limitations.

Localization, presence and awareness features

may add value to communication applications by

augmenting the usual status (such as “busy” or

“away”) and mood indicators (Perey, 2008) with

real-time indication of a friend's location and

availability. Perey (2008) raises an important point

about status indicators in Mobile Communication

applications: given the fact that multi-tasking is

much more difficult in the limited-screen mobile

device, visual indicators for a user's availability to

engage in interaction becomes even more important

than in web applications. Moreover, traditional

mobile communication channels like SMS, MMS,

voice and video-calls may be integrated in order to

increment communication efficiency.

5.4 Mobile Social Network

In the words of Humphreys (2008), mobile social

network applications that “purport to allow people to

create, develop, and strengthen social ties” are

“much like social network sites on the Internet”.

Using the interaction construct, it means that Mobile

SNA is aimed at the same interaction focus than

Web 2.0 SNA: user-user interactions.

However, a pure transposition may be too

simplistic. Humphreys (2008) himself reports

differences in structure and use between Dodgeball,

a mobile SNA enhanced with localization features,

and typical Web 2.0 SNA. Dodgeball is heavily

dependent on location-based information, allowing

the articulation of social networks around places, not

content or people. Similarly, it is interesting to see

how users understand the system: “Dodgeball differs

from Friendster in that it involves 'real world

interactions'”. In other words, according to the users,

the location-based component of the Mobile SNA

truly facilitates face-to-face interactions, as opposed

to virtual interactions that characterizes online SNA.

This may be interpreted as an indication of how

mobility can impact use and design of Mobile SNA.

Perey (2008), on the other hand, indicates that

Mobile SNA interaction focus may be dislocated in

the direction of user-user-content interactions. She

argues that, given mobile device's characteristics,

collective UGC share and consumption tend to be

more relevant than social relationships.

5.5 Mobile Social Networking

As with other application categories, also Web 2.0

Social Networking may be enhanced with mobility.

All Mobile Social Network applications share the

basic characteristics of user-user interaction focus

aimed at making new acquaintances and are

supported by communication tools. However, the

most sophisticated ones build up on detailed profile,

closed list of connections and profile matching, and

its implementation may be enhanced by localization,

presence and awareness features. On the other hand,

the most simple and archaic ones are basically just

chat rooms, usually with little or no profiling, where

interaction may be restricted to as little as text-only

communication (Perey, 2008).

6 CONCLUSIONS

In the context of the recent attention given to the

Web 2.0 phenomenon and the ambiguousness that

characterises it, this paper analyses published

research about Web 2.0 in order to identify

interaction as a common construct among the

diverse definition approaches. A taxonomy schema

for Web 2.0 applications is then proposed, based on

interaction as the categorizing construct. Finally, the

concept of Mobile 2.0 is discussed, and the

taxonomy schema is extended to Mobile 2.0

applications. Furthermore, some considerations

about the implications of mobility characteristics are

presented.

The proposed taxonomy schema may be used as

a reference framework for empirical studies

involving Web 2.0 or Mobile 2.0 applications. It

may be particularly useful when comparing

applications from both technology domains.

Exploratory and descriptive studies are needed to

validate the schema, to draw additional insight about

using interaction as the classificatory construct, and

to test the boundaries of the proposed category

types.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C., 2006. The Long Tail: Why the future of

business is selling less for more, Hyperion, New York.

Anderson, P., 2007. What is Web 2.0? Ideas, technologies

and implications for education, JISC Technology and

Standards Watch, available at http://www.jisc.ac.uk/

media/documents/techwatch/tsw0701b.pdf (accessed 2

March 2009).

A TAXONOMY SCHEMA FOR WEB 2.0 AND MOBILE 2.0 APPLICATIONS

75

Barsky, E., Purdon, M., 2006a. Introducing Web 2.0:

social networking and social bookmarking for health

librarians, Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries

Association, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 65-67.

Barsky, E., Purdon, M., 2006b. Introducing Web 2.0:

weblogs and podcasting for health librarians, Journal

of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, Vol.

27, No. 2, pp. 33-34.

Berners-Lee, T., 1999. Weaving the Web, Harper, San

Francisco.

Bishop, J., 2009. Understanding and Facilitating the

Development of Social Networks in Online Dating

Communities: A Case Study and Model. In: Romm, C.

& Setzekorn, K., Social Networking Communities and

E-Dating Services – Concepts and Implications, IGI

Global, Hershey.

Boyd, D. M., Ellison, N.B., 2008. Social Network Sites:

Definition, History, and Scholarship, Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 13, No. 1,

pp. 210-230.

Clarke, I., 2001. Emerging value propositions for m-

commerce, Journal of Business Strategies, Vol. 18, No. 2,

pp. 133-148.

Constantinides, E., Fountain, S.J., 2008. Web 2.0:

Conceptual foundation and marketing issues, Journal

of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, Vol.

9, No. 3, pp. 231-244.

Cox, A. M., 2008. Flickr: a case study of Web 2.0, Aslib

Proceedings: New Information Perspectives, Vol. 60,

No. 5, pp. 493-516.

Ducheneaut, N., Yee, N., 2009. Collective Solitude and

Social Networks in World of Warcraft. In: Romm, C.

& Setzekorn, K., Social Networking Communities and

E-Dating Services – Concepts and Implications, IGI

Global, Hershey.

Eijkman, H., 2008. Web 2.0 as a non-foundational

network-centric learning space, Campus-Wide

Information Systems, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 93-104.

Fu, F., Liu, L., Wang, L., 2008. Empirical analysis of

online social networks in the age of Web 2.0, Physica

A, Vol. 387, No. 2-3, pp. 675-684.

Griswold, W.G., 2007. Five Enablers for Mobile 2.0,

Computer, Vol. 40, No. 10, pp. 96-98.

Hearn, G., Foth, M., Gray, H., 2009. Applications and

implementations of new media in corporate

communications – An action research approach,

Corporate Communications: An International Journal,

Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 49-61.

Hendler, J., Golbeck, J., 2007. Metcalfe's law, Web 2.0,

and the Semantic Web, Web Semantics: Science,

Services and Agents on the World Wide Web, Vol. 6,

No. 1, pp. 14-20.

Humphreys, L., 2008. Mobile Social Networks and Social

Practice: A Case Study of Dodgeball, Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 13, No. 1,

pp. 341-360.

Jaokar, A., Fish, T., 2006. Mobile Web 2.0: The innovator's

guide to developing and marketing next generation

wireless/mobile applications, Futuretext, London.

Jeon, J., Lee, S., 2008. Technical Trends of Mobile Web

2.0: What Next? In WWW 2008, 17

th

International

World Wide Web Conference, Beijing (China).

Levy, M., 2009. WEB 2.0 implications on knowledge

management, Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 120-134.

Lugano, G., 2007. Mobile Social Software: Definition,

Scope and Applications. In eChallenges 2007

Conference. The Hague (Netherlands), pp. 1434-1441.

Oberhelman, D. D., 2007. Coming to terms with Web 2.0,

Reference Reviews, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 5-6.

O'Reilly, T., 2005. What is Web 2.0? Design patterns and

business models for the next generation of software,

available at http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly

/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-isweb-20.html (accessed 2

March 2009).

Parameswaran, M., Whinston, A.B., 2006. Social

Computing: An Overview, The Communications of the

Association for Information Systems, Vol. 19, Article

37, pp. 762-780-

Parker, L., 2008. Second Life: the seventh face of the

library?, Program: electronic library and information

systems, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 232-242.

Perey, C., 2008. Mobile Social Networking: Communities

and Content on the Move, Informa UK Ltd London.

Scale, M., 2008. Facebook as a social searchengine and

the implications for libraries in the twenty-first

century, Library Hi Tech, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 540.556.

Subrahmanyam, K., Reich, S.M., Waechter, N., Espinoza,

G., 2008. Online and offline social networks: Use of

social networking sites by emerging adults, Journal of

Applied Developmental Psychology, Vol. 29, No. 6,

pp. 420-433.

Thelwall, M., 2009. MySpace comments, Online

Information Review, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 58-76.

Wunsch-Vincent, S., Vickery, G., 2007. Participative

Web: User-Created Content, available at http://www.

oecd.org/dataoecd/57/14/38393115.pdf (accessed 2

March 2009).

Wusteman, J., 2004. RSS: the latest feed, Library Hi Tech,

Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 404-413-

Wyld, D.C., 2008. Management 2.0: a primer on blogging

for executives, Management Research News, Vol. 31,

No. 6, pp. 448-483.

Zimmerman, E., Bar-Ilan, J., 2009. PIM @ academia: how

e-mail is used by scholars, Online Information Review,

Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 22-42.

ICE-B 2009 - International Conference on E-business

76