REHEARSING FOR THE FUTURE

Scenarios as an Enabler and a Product of Organizational Knowledge Creation

Hannu Kivijärvi

Department of Information Systems, Helsinki School of Economics, P.O. Box 1210, 00101 Helsinki, Finland

Kalle Piirainen, Markku Tuominen

Department of Industrial Management, Lappeeranta University of Technology, P.O. Box 20, 53851 Lappeenranta, Finland

Keywords: Personal knowledge, Organizational knowledge, Communities of practice, Virtual communities, Scenarios,

Scenario planning.

Abstract: This paper discusses conceptual basis for facilitating knowledge creation through the rehearsal of plausible

futures in the scenario process. We discuss the foundations for creating knowledge in an organizational

context and propose a concrete context that supports and stimulates the conversion of personal knowledge

organizational knowledge and decisions. Based on the discussion and our experiences with the scenario

process, we argue that the scenario process facilitates creation of organizational knowledge. We propose

that the scenario process acts as a vehicle for exploring and creating organizational knowledge.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge and knowledge sharing are important to

any modern organization. The quality of decision

making depends on creation, transformation and

integration of knowledge across individuals and

organizational groupings. Knowledge enables

effective decision making and management. As

organizations have become larger and more

diversified, and as individual roles and tasks have

become more specialized, there is a growing need to

convert personal knowledge to common usage.

Every decision situation in organizational

decision making involves a decision maker or

decision makers, desired outcomes or objectives and

goals, at least two decision alternatives, and an

environment or a context. In addition, an implicit

assumption of every decision situation is the future

oriented conception of time; decisions are

meaningful only with reference to the future. They

are made for future not for past or present.

The rapid rate of technological, economic and

social changes that have an effect on organizational

environment has increased the need for foresight.

Because the future in absolute term is always at least

partly unknown, it cannot be predicted exactly. The

external environment is not under the control of the

organization and therefore the environment is a

source of uncertainty. Still, every organization can

practise foresight. The ability to see in advance is

rooted in present knowledge and in partially

unchanging routines and processes within an

organization. The quality of attempts to foresee is

finally grounded on our knowledge and ability to

understand deeply enough the present position.

A class of such foresight action is the process

aiming to produce plots that tie together the driving

forces and key actors of the organizational

environment (Schwartz, 1996), i.e. scenarios.

Although future oriented, scenarios are also

projections of the known, extensions of the present

situation over into the unknown future.

Nevertheless, even if scenarios are projections of the

known, they still have value as representations of

organizational knowledge.

Concepts like the community of practice (Lave

and Wenger, 1991) and networks of practice (Brown

and Duguid, 2001a) are used to explain the

organizational conditions favoring knowledge

creation and sharing and innovation. The most

favorable contents of these arrangements certainly

depend on factors such as the organizational context,

the experiences and other capabilities of the

members, and management style.

This paper discusses the theoretical basis for

creating conditions to support formation of a

community to enable knowledge sharing and goes

46

Kivijärvi H., Piirainen K. and Tuominen M. (2009).

REHEARSING FOR THE FUTURE - Scenarios as an Enabler and a Product of Organizational Knowledge Creation.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, pages 46-54

DOI: 10.5220/0002297700460054

Copyright

c

SciTePress

on to propose such a condition or an artifact. The

paper presents a possible means to support

knowledge transfer and creation through the

scenario process. We argue that the electronically

mediated scenario process can act as a community

and enable the participants to share their knowledge

while exploring the future. In this paper, the

potential value of the proposed approach is

evaluated mainly by epistemological criteria.

The question to which we seek answer is: ‘What

kind of organizational arrangements are capable to

increase organizational knowledge creation?’ and

also more specifically ‘Can the scenario process

support organizations in their strive towards

knowledge creation?’.

The remainder of the paper is organized as

follows. The second section discusses knowledge

and its creation in organizational contexts. The third

section presents the scenario process and discusses

its properties as a venue for knowledge creation. The

fourth and last section discusses the results and

presents conclusions at theoretical and practical

levels.

2 CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Knowledge and Knowing

Knowledge is traditionally interpreted as a singular,

independent object. Another, procedural

interpretation of knowledge is to see it as a path of

related steps (Carlile and Rebentisch, 2003). When

defining knowledge, Tsoukas and Vladimirouv

(2001, p. 979) relate knowledge to a person’s ability

to draw distinctions: “Knowledge is the individual

ability to draw distinctions, within a collective

domain of action, based on an appreciation of

context or theory, or both.” According to this

definition, a person who can draw finer distinctions

is more knowledgeable. Making distinctions and

judgments, classifying, structuring, placing order to

chaos, are capabilities of an expert who has

knowledge.

If decision making is not a synonym for

management, as Simon (1960) has argued, decision

making is still undoubtedly at the core of all

managerial functions. When a decision is made, the

epistemic work has been done and the physical work

to implement the decision can start. The value of

knowledge and information is ultimately evaluated

by the quality of the decisions made. Making

decisions involves also making distinctions,

categorizations and judgments – we need to search

for and structure alternatives. According to Emery

(1969, p. 67) information has value only if it

changes our view of the world, if our decisions are

sensitive to such a change, and if our utility is

sensitive to difference in decisions. Thus,

information is valued through decisions and because

information and knowledge are relative, the same

logic can be used to value knowledge, too. Kivijärvi

(2008) has elaborated the characterization of

knowledge further and defines knowledge as the

individual or organizational ability to make

decisions; all actions are consequences of decisions.

Also Jennex and Olfman (2006, p. 53) note that

“...decision making is the ultimate application of

knowledge”.

When Polanyi (1966) talks of knowledge in his

later works, especially when discussing tacit

knowledge, he actually refers to a process rather

than objects. Consequently, we should pay more

attention to tacit knowing rather than tacit

knowledge. Zeleny (2005) characterizes the

relationship of explicit and tacit knowledge much in

the same way as Polanyi. He (Zeleny, 2005) sees

that knowledge is embedded in the process of

‘knowing’, in the routines and actions that come

naturally for a person who knows. Cook and Brown

(1999) also emphasize that knowing is an important

aspect of all actions, and that tacit knowledge most

easily becomes evident when it is used, that is, it

will manifest itself during the knowing process.

Polanyi (1962) tied personal dimension to all

knowledge and his master-dichotomy between tacit

and explicit knowledge has shaped practically all

epistemological discussion in knowledge

management field. According to Polanyi tacit

knowledge has the two ingredients, subsidiary

particulars and focal target (proximal and distal,

Polanyi, 1966, p. 10). Subsidiary particulars are

instrumental in the sense that they are not explicitly

known by the knower during the knowing process

and therefore they remain tacit. Thus, “we can know

more than we can tell” (Polanyi, 1966, p. 4) or even

“we can often know more than we can realise”

(Leonard and Sensiper, 1998, p. 114) and we cannot

directly convert tacit knowledge to explicit

knowledge.

Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001, p. 981) write

“Organizational knowledge is the set of collective

understanding embedded in a firm”. It is “the

capability the members of an organization have

developed to draw distinctions in the process of

carrying out their work, in particular concrete

contexts, by enacting sets of generalizations

(propositional statements) whose application

depends on historically evolved collective

REHEARSING FOR THE FUTURE - Scenarios as an Enabler and a Product of Organizational Knowledge Creation

47

understandings and experiences” (Tsoukas and

Vladimirou, 2001, p. 983). Similar to the way the

definition of personal knowledge was extended, the

above definition of organizational knowledge has

been extended as the capability the members of an

organization have developed to make decisions in

the process of carrying out their work in

organizational contexts (Kivijärvi, 2008).

2.2 Contexts for Knowledge Creation

and Sharing

Lave and Wenger (1991, p. 98) introduced the

concept of community of practice and regarded it as

“an intrinsic condition for the existence of

knowledge”. Communities of practice have been

identified as critical conditions for learning and

innovation in organizations, and they are formed

spontaneously by work communities without the

constraints of formal organizations. According to

Lesser and Everest (2001, p. 41) “Communities of

practice help foster an environment in which

knowledge can be created and shared and, most

importantly, used to improve effectiveness,

efficiency and innovation”. In other words, a

community of practice can form the shared context,

which supports the recipient decoding a received

message with the same meaning the sender has

coded it (Gammelgaard and Ritter, 2008). Although

the communities develop informally and

spontaneously, the spontaneity can be structured in

some cases (Brown and Duguid, 2001b).

When people are working together in

communities, knowledge sharing is seen as a social

process, where the members participate in

communal learning at different levels and create a

kind of ‘community knowledge’. According to the

studies on communities of practice, new members

learn from the older ones by being allowed to

participate first in certain ‘peripheral’ tasks of the

community. Later the new members are approved to

move to full participation. After the original

launching of the concept of community of practice, a

number of attempts have been made to apply the

concept to business organizations and managerial

problems (Brown and Duguid, 1996). Recent studies

on communities of practice have paid special

attention to the manageability of the communities

(Swan, Scarbrough, Robertson, 2002), alignment of

different communities, and the role of virtual

communities (Kimble, Hildreth, Wright, 2001).

Gammelgaard and Ritter (2008), for example,

propagate virtual communities of practice, with

certain reservations, for knowledge transfer in

multinational companies.

To sum up, the general requirements for a

community are a common interest, a strong shared

context including own jargon, habit, routines, and

informal ad hoc relations in problem solving and

other communication (Amin and Roberts, 2008). An

important facet of a community of practice is that

the community is emergent, and is formed by

individuals who are motivated to contribute by a

common interest and sense of purpose. A cautious

researcher might be inclined to use the term quasi-

community or some similar expression in the case of

artificial set-ups, but in the interest of being

succinct, we use the word community in this paper

also for non-emergent teams.

2.3 Scenarios and the Scenario Process

Kahn and Wiener (1967, p. 33) define scenarios as

“Hypothetical sequences of events constructed for

the purpose of focusing attention to causal processes

and decision points”, with the addition that the

development of each situation is mapped step by

step, and the decision options of each actor are

considered along the way. The aim is to answer the

questions “What kind of chain of events leads to a

certain event or state?” and “How can each actor

influence the chain of events at each time?” This

definition has similar features as Carlile and

Rebentisch’s (2003) definition of knowledge as a

series of steps as discussed above.

Schwartz (1996) describes scenarios as plots that

tie together the driving forces and key actors of the

environment. In Schwartz’ view the story gives a

meaning to the events, and helps the strategists to

see the trend behind seemingly unconnected events

or developments. The concept of ‘drivers of change’

is often used to describe forces such as influential

interest groups, nations, large organizations and

trends, which shape the operational environment of

organizations (Schwartz, 1996; Blanning and Reinig,

2005). We interpret that the drivers create movement

in the operational field, which can be reduced to a

chain of related events. These chains of events are in

turn labeled as scenarios, leading from the present

status quo to the defined end state during the time

span of the respective scenarios.

The scenario process is often considered as a

means for learning or reinforcing learning, as

discussed by Bergman (2005), or a tool to enhance

decision making capability (Chermack, 2004).

Chermack and van der Merwe (2003) have proposed

that often participation in the process of creating

scenarios is valuable in its own right. In their view

(Chermack and van der Merwe, 2003) one major

product in successful scenarios is a change in the

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

48

participants view to the world and the subject area of

the scenarios. This is another feature that has echoes

in knowledge management field, as Emery (1969)

proposed that one of the conditions information has

to fulfill to have value, is that it changes our

worldview, and here Chermack and van der Merwe

(2003) argue that participation in scenario process

will potentially change the participants worldview.

They argue further that even the most important aim

of scenario process is to challenge the participants’

assumptions of the future and let them to re-examine

their assumptions analytically. In short, they argue

that a learning process enables the participants to

examine their assumptions and views, challenges

them and as a result, improve the existing mental

structures.

When we contrast these properties of scenarios

as a product and a process to the discussion about

knowledge, we will notice that knowledge is

manifested in knowing, decision making and action.

Scenarios on the other hand enable simulation of

action, through analysis of the current situation and

analytical projections from the assumptions. So we

can propose that scenarios 1) as a process can be a

learning experience, but scenarios 2) as projections

of future can be manifestations of knowledge about

the present and future, and lastly scenarios 3) as

stories of plausible futures can act as a rehearsal for

the future, testing of present knowledge and routines

in different environments.

To put these proposition to plain terms: Firstly,

the process forces the participants to think about the

present, the drivers of the situation and where does it

evolve, and through critical discussion in the group

the process guides the participants to critically

examine their mental models and to converge toward

a commonly agreed statement of futures. Secondly,

the scenarios as a product codify and make the

assumptions explicit and illustrate the created

knowledge of the future at that given point of time.

And thirdly, when the group creates plausible stories

of the world of tomorrow, they can be used as a

framework for reflecting existing knowledge and

mental models, and their fitness to the new

situations.

2.4 Linking the Conceptual Elements

We proposed that in its deepest sense knowledge is

and manifests as capability to make decisions.

Scenarios, as discussed above, can be linked to

organizational learning and knowledge on multiple

levels. Scenarios aim to increase the organizational

capability to make decisions and are thus, by

definition, a type of organizational knowledge and

most of all projections of present knowledge.

Knowledge is also tied to action and scenarios are a

kind of ‘quasi-action’ where knowledge items can be

tested in relation to other items.

In addition to the scenarios, the process of

creating them helps the members of the community

to use their deepest, subsidiary awareness of the

future. All foresights have a tacit, hidden dimension,

which is like all tacit knowledge partly consciously

known, whereas the other part is instrumental and is

known only at the subsidiary level. Subsidiary

awareness forms a background or context for

considering the future. It is a part of our foresights

that cannot be directly articulated in explicit form

but when those foresights are used in the knowing

process their content will be manifested. Thus, the

scenario process is a foreseeing process where the

subsidiary awareness of each participant is

transformed into organizational scenarios. The final

measure of scenarios is how well the subsidiary and

focal awareness of the community members are

stimulated. Organizational scenarios are a future

oriented type of organizational knowledge grown

from the individual as well as organizational

knowledge concerning the past and present.

If we accept these premises, we can argue that

scenarios enable ‘rehearsing for the future’ and

presenting knowledge of the present as well as

future. The remaining question is then how to

manage the process effectively to organize and

transform available knowledge to logical scenarios.

One question is whether the process satisfies the

conditions of being a community, and if the

community in the case is not emergent, but

purposefully set up, is still a community? The

answer of Amin and Roberts (2008) would most

likely be ‘yes and no’, and the short-lived

community this paper presents would be classified

as a ‘creative community’, where the base of trust is

professional and the purpose is to solve a problem

together.

The experimental community we propose in this

study is a group support system facility, which is

used to mediate the interaction and to support the

community in the task of composing scenarios. The

method adopted in this study is the intuitive

decision-oriented scenario method, which uses

Groups Support Systems (GSS) to mediate group

work in the process. The method is introduced by

Kivijärvi, Piirainen, Tuominen, Kortelainen and

Elfvengren (2008) and later labeled the IDEAS

method (Piirainen, Kortelainen, Elfvengren,

Tuominen, 2010).

REHEARSING FOR THE FUTURE - Scenarios as an Enabler and a Product of Organizational Knowledge Creation

49

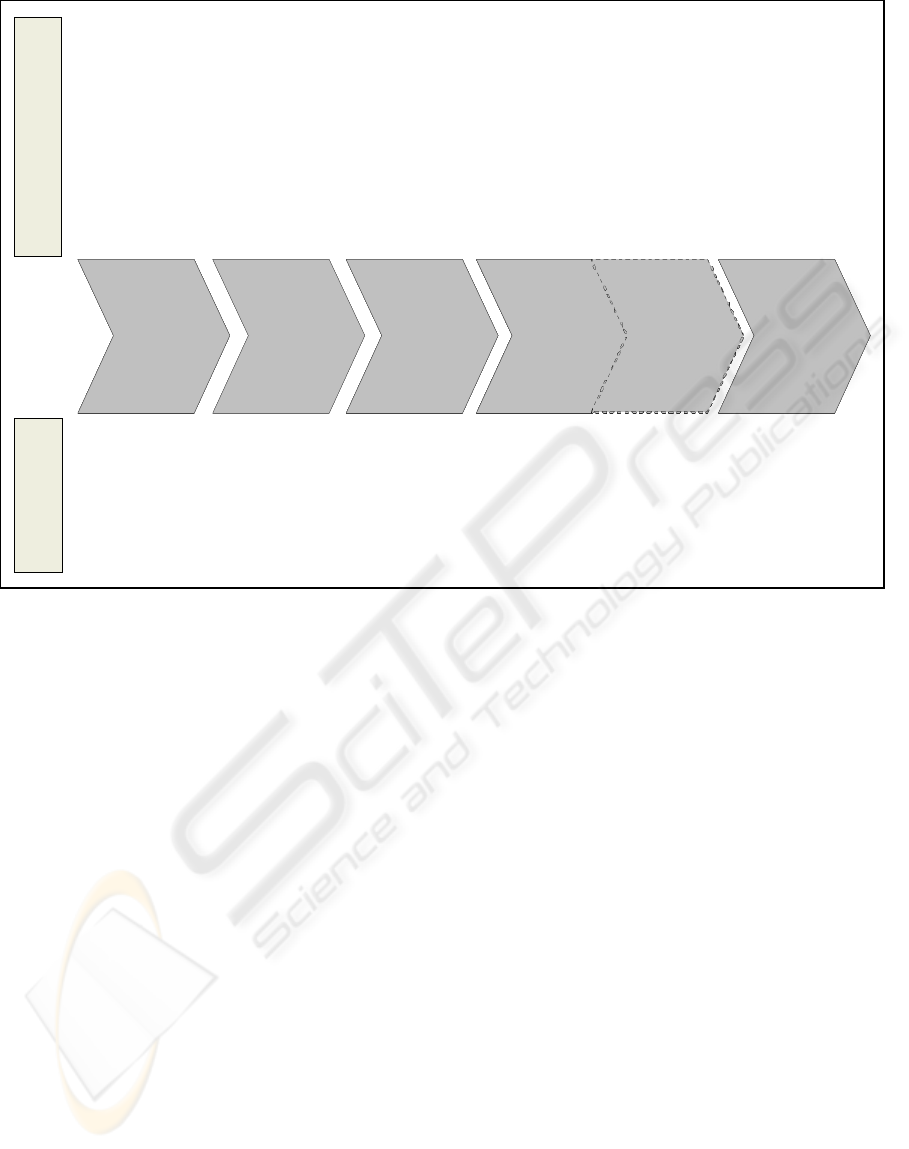

PRE-PHASE

OBJECTIVE

DEFINITION

PREPARATIONS

(PRE-MEETING)

POST-PHASE

FORMING OF THE

FINAL SCENARIOS

IMPLEMENTATION

TO USE

I S

PROCESS PHASES

AA

PHASE IV

REVIEW OF THE RESULTS

ITERATION IF NEEDED

ED

PHASE III

EVALUATIONS OF THE EVENTS

GROUPING THE EVENTS TO

SCENARIO SETS

PHASE I

IDENTIFICATION

OF THE

DRIVERS OF

CHANG E

PHASE II

IDENTIFICATION

OF PROBABLE

EVENTS

(BASED ON THE

DRIVERS)

PRE-PHASE

OBJECTIVE

DEFINITION

PREPARATIONS

(PRE-MEETING)

POST-PHASE

FORMING OF THE

FINAL SCENARIOS

IMPLEMENTATION

TO USE

I S

PROCESS PHASES

AA

PHASE IV

REVIEW OF THE RESULTS

ITERATION IF NEEDED

E

PHASE III

EVALUATIONS OF THE EVENTS

GROUPING THE EVENTS TO

SCENARIO SETS

PHASE I

IDENTIFICATION

OF THE

DRIVERS OF

CHANG E

PHASE II

IDENTIFICATION

OF PROBABLE

EVENTS

(BASED ON THE

DRIVERS)

TOOLS

GROUP

SUPPORT

SYSTEM

GROUP

SU P P OR T

SYSTEM

GROUP

SUPPORT

SYSTEM

CONC EPT UAL

MAPS

GROUP

SUPPORT

SYSTEM

CONCEPTUAL

MAPS

Figure 1: The IDEAS scenario process and support tools (adapted from Lindqvist, Piirainen, Tuominen, 2008).

3 KNOWLEDGE CREATION IN

THE SCENARIO PROCESS

The discussion above presented the argument that

scenarios can enable knowledge creation and storing

it. We already referred to the IDEAS method which

has been developed to enable efficient scenario

creation with electronic mediation. The method uses

a group support system to facilitate group work and

to enhance interaction.

The often cited benefits of using a GSS are

reduction of individual domineering, efficient

parallel working, democratic discussion and decision

making through anonymity on-line and voting tools

(e.g. Kivijärvi et al., 2008; Fjermestad and Hiltz,

2001; Nunamaker, Briggs, Mittleman, Vogel,

Balthazard, 1997). These features are important

features where the subjects may be sensitive or

controversial to some of the participants. The

mechanical details of the process has been described

and discussed in detail in previous publications

(Piirainen, Tuominen, Elfvengren, Kortelainen,

Niemistö, 2007; Kivijärvi et al., 2008).

3.1 The Scenario Process

To illustrate how the scenario process works, we

walk through the main tasks. The phases are also

illustrated in Figure 1.

The phases I-IV are completed in a group

session under electronic mediation, preceded by

common preparations and after the session the

collected data is transformed to the final scenarios.

The phases from III-post-phase can be also

supported by mapping tools beside GSS.

The first main task during the process is to identify

the drivers of change, the most influential players,

change processes and other factors, which constrain

and drive the development of the present. The

second is to identify events, these drivers will trigger

during the time span of the scenarios. As a third

task, the group will assign an impact measure on the

events based on how much they think the event will

affect the organization or entity from whose point of

view the scenarios look upon the future, and a

probability measure to tell how probable the

realization of each event is. These measures are used

to group the events to sets as the fourth task, which

make the scenarios. The grouping is inspected and

discussed in the session and consistency of the

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

50

events is inspected. The event and drivers will act as

a base for the final scenario stories that will be

written outside the session.

When we compare the process to the discussion

about learning process and knowledge presented

above, we learn that the process follows the formula

where the participants articulate their assumption

when generating the drivers that change the world.

The subsequent discussion will subject the

assumptions to scrutiny and the group mover toward

new critically chosen set of assumptions when they

vote for the most important drivers. Then they

extrapolate assumptions when identifying the future

events and when evaluating the events the

participants effectively have to picture plausible

actions and their effects. This makes for two of the

three suggested uses of scenarios. The final

scenarios are presented outside the session.

3.2 Cases

The conceptual discussion above presented the

premises for the argument that using a scenario

process would form a community that encourages

knowledge creation and sharing within an

organization. To pave the way for the evaluation of

our argument, we preset two concise case

descriptions to illustrate the process. The first case

focuses on strategic planning and positioning in a

university (Piirainen et al., 2007). The second case is

taken from a project where the objective was to

develop measures to identify and assess business

opportunities at an intersection of industries

(Piirainen et al., 2010). The cases both use the same

process context although the communities are

different.

The members of the semi-virtual community in

the first case hold personal knowledge and

experience in a number of areas such as research,

teaching, and administration in different departments

and in the administration of the whole university.

The purpose was to discover new opportunities for

the future position and operational environment of

the university over the following ten years. The

community was composed of individuals most of

whom had met but who were not very familiar with

each other. Thus, the most apparent link between

most of the individuals was the presented problem of

creating scenarios for the organization.

After the preparation, definition, and briefing of

the problem, the actual work within the community

started by brainstorming the key external

uncertainties and drivers of change. The drivers

form the backbone of the scenarios. This phase

comprised an idea generation with a brainstorming

tool, followed by a period for writing comments

about the ideas and clarification of the proposed

drivers. The discovered events they were grouped

into initial scenarios by qualitative graphical

clustering and discussed during the meeting. The

GSS-workshop phase of the process ended in the

evaluation of the events and graphical grouping,

from which the data was moved to the remainder of

the process.

The authors of the scenarios reflected on the

cause and effect between drivers and events inside

the scenario through systems thinking. Using

systems analogy, the drivers of the scenarios form a

system with feed-back relations, and the event are

triggered by the interaction and feedback between

the drivers. After mapping the drivers and the data

cleanup, the events were organized into a concept

map and tied together as logical chains with

appropriate linking phrases; these described the

connection and transition between the events. The

names for the scenarios were picked after examining

the general theme in the scenarios. In this case, in

order to test the reactions and validate the logical

structure of the maps, after the initial maps were

drawn they were presented to some of the closer

colleagues familiar with the sessions in the form of a

focus group interview.

The final scenario stories were written around

the logic of the concept maps. Other than some

minor adjustment to the maps, the writing was a

straightforward process of tying the events together

as a logical story, from the present to a defined state

in the future. The process might be characterized as

iterative, a resonance between the drivers and the

scenario maps conducted by the writer.

The purpose of the second case was to discover

new opportunities at the intersection of a

manufacturing and a complementary industry. For

this case, the members of the semi-virtual

community were selected from each industry, as

well as from academics and general experts in the

field. The working process followed the same

outline as the previous case described above. The

process outline was similar and the community was

able to produce plausible scenarios also in the

second case. Regarding this paper, the contribution

of the second case was to confirm the observations

together with the first case, following the replication

logic.

REHEARSING FOR THE FUTURE - Scenarios as an Enabler and a Product of Organizational Knowledge Creation

51

Table 1: Epistemological criteria for evaluating scenario processes.

Theoretical concept Evaluation criteria for the support system

Personal knowledge The support system has to

1. Object

Support in making categories and distinctions and organizing primary knowledge elements

from the huge mass of knowledge and information overflow.

2. Path Support creation of procedural knowledge by related steps.

3. Network

Help to create new relations between the knowledge elements and to relate participants over

organization.

4. Tacit

Stimulate sharing and usage of tacit knowledge by providing a shared context for social

processes; accepts personal experience.

5. Explicit Support codification and sharing/diffusing of explicit knowledge assets.

6. Knowing

Integrates subjective, social, and physical dimensions of knowledge in the epistemic process of

knowing. Support the interplay between the different types of knowledge and knowing.

Organizational knowledge

1. Knowledge

Support creating organizational knowledge within the organization and with value chain

partners.

2. Knowing Support organizational decision making by applying organizational rules of actions.

Context

1. Participation Allow equal opportunity for participation.

2. Spontaneity Diminish bureaucracy but allow to structure spontaneity. Keep the feeling of voluntarity.

3. Self-motivation

Support self-determination of goals and objectives. Allow the possibility to choose the time of

participation. Explicate clear causality between personal efforts, group outcomes and personal

outcomes.

4. Freedom from

organizational

constraints

Manage participants from different organizational units at various organizational levels.

5. Networking

Allow traditional face to face communication to promote mutual assurance between

participants. Allows freedom of expression, verbal and non-verbal communication. Maintain

social networking among participants.

Scenario

1. Subsidiary

awareness

Engage subsidiary and focal awareness of the past and future.

2. Focal awareness

3. Foreseeing Support the continuous process to integrate past, present and future.

4. Driver Enable electronic discussion voting tools to identify of important drivers.

5. Event Enable discussion and voting tools.

6. Chains of events

Provide maps and other representations to organize the knowledge of future drivers and events

to scenarios.

7. Phases of the

process

Accumulate information about the future and converge toward shared knowledge toward the

end of the process.

3.3 Evaluating the Proposed Approach

Reportedly, the presented scenario method has

served adequately in each context. The participants

of the sessions have generally reported the approach

as a viable tool for large and important decisions,

even with its flaws. In addition to the concrete

scenarios, some interviewees also saw the process as

a kind of learning experience, promoting open-

minded consideration of different options and ideas,

and as a possibility to create consensus on large

issues and goals in a large heterogeneous

organization. However, the knowledge production

properties have not been explicitly investigated in

the reported cases.

The answer to the question of whether

knowledge has been created is not straightforward.

One factor influencing the outcome was that the

definition of ‘knowledge’ or knowledge creation

was none too familiar to the subjects and the

definitions were somewhat equivocal. In any case,

the results still point to the fact that the subjects in

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

52

the sessions were forming a community, exchanged

and diffused knowledge through the system, which

in effect supports the argument in the paper. If we

accept that conceptually scenarios are an

embodiment of organizational knowledge, then a

process which produces scenarios successfully

indeed does create knowledge. Together with the

fact that the reported satisfaction to the results and

general buy-in to the scenarios is high, we can at

least suggest that the scenarios done with the IDEAS

method do have properties of organizational

knowledge.

The results may also apply to other scenario

methods, as long as there is a group of people who

actively participate in creating the scenarios, so that

the conditions for community and knowledge can be

satisfied. IDEAS is in that sense a well

representative example, because the main substance

in the scenarios is essentially a product of group

discussion, where the group expresses their views,

discusses and reiterates the scenario material

towards a consensus where they can agree upon the

drivers and sets of events.

Table 1 summarizes the evaluation of the

scenario process by epistemological criteria

discussed in section 2. Generally, the properties of

the semi-virtual community and the scenario process

meet the conceptual criteria set up for the scenario

process The GSS in general and also reportedly in

this case allows democratic participation to the

process and enables people to share their knowledge.

The properties of GSS also support transfer of the

input to the rest of the process quite conveniently.

The properties of GSS as a tool for the scenario

process are discussed in the cited cases and the

system has been evaluated as suitable.

Here we would like to conclude that the

properties of the IDEAS-method as a community

will also facilitate knowledge creation. However, we

must leave a reservation that these conclusions are

based on theoretical reasoning and two cases, and

thus our results serve to highlight an interesting

direction for further research in scenarios as both as

a product and enabler of knowledge creation in

organizations.

4 DISCUSSIONS

We started the paper by arguing that scenarios are a

piece of organizational knowledge and can be linked

to knowledge creation in different levels. The main

premise was that knowledge is capability to make

decisions. A further premise is that the shared

context can be provided in a community of practice,

or in the absence of a community of practice, in a

semi-virtual facilitated community. We also

presented a method to create scenarios and examined

a case study which offers some support to our

argument. Generally, proposed approach fits to the

conceptual requirements and the empirical

experiences with the system suggest that the process

is able to promote knowledge creation, sharing.

Examination of the results suggested that the

cases supported the theoretical propositions about

supporting the semi-virtual community. In the light

of the results, it seems that the concept of utilizing

the supported scenario process to create actionable

knowledge is feasible. Nevertheless, we would like

to be cautious about drawing definite conclusions,

but instead we would like to encourage further

research in to knowledge creation in the scenario

process and scenarios as a product of knowledge

creation.

In the academic arena, the paper has contributed

to the discussion about communities of practice and

tested the use of communities for promoting

knowledge creation. As for practical implications,

the results suggest that the scenario process can

facilitate integration and embodiment of

organizational knowledge otherwise left tacit.

The subject of scenarios as an embodiment of

organizational knowledge can be studied further in a

variety of directions. One interesting question is that

how much we can in fact know about the future, and

how much scenarios are representations of current

knowledge. Also the properties of scenarios as a way

to rehearse for future actions would be an interesting

subject for further study.

To conclude the paper, we propose that as far as

knowledge is capability to make decisions, managers

can raise their knowledge and capability to make

decisions by undertaking the scenario process.

Altogether, the case experiences suggest that the

approach was at least partially able to engage the

group in a semi-virtual community and to facilitate

knowledge creation in the organizational context.

The proposed scenario process seems to be a

feasible way to integrate multidisciplinary groups to

create knowledge in the form of the scenarios, which

can be used to promote knowing future opportunities

and decision options. The properties of scenarios

promote and even require open minded

consideration of the plausible beside the known and

probable, which raises situation awareness and

improves ability to act. With these conclusions, we

would like to encourage further study into scenarios

as a product and enabler of organizational

knowledge creation.

REHEARSING FOR THE FUTURE - Scenarios as an Enabler and a Product of Organizational Knowledge Creation

53

REFERENCES

Amin, A., Roberts, J., 2008. Knowing in action, beyond

communities of practice. Research Policy, 37, 353-

369.

Bergman, J-P., 2005. Supporting Knowledge Creation and

Sharing in the Early Phases of the Strategic

Innovation Process. Acta Universitatis

Lappeenrantaesis 212. Lappeenranta University of

Technology. Lappeenranta FI.

Blanning R. W., Reinig, B. A., 2005. A Framework for

Conducting Political Event Analysis Using Group

Support Systems. Decision Support Systems, 38, 511-

527.

Brown, J.S., Duguid, P., 1996. Organizational Learning

and Communities-of-Practice: Toward a Unified View

of Working, Learning, and Innovation. In Cohen, M.

D., Sproull, L. S. eds. Organizational Learning, 58-82,

Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, CA.

Brown J. S., Duguid, P., 2001a. Knowledge and

organization: A social-practice perspective.

Organization science, 12(2), 198-213.

Brown, J. S., Duguid, P., 2001b. Structure and

Spontaneity: Knowledge and Organization. In:

Nonaka I. Teece, D. eds. Managing Industrial

Knowledge, 44-67, Sage. London.

Carlile P., Rebentisch, E. S. 2003. Into the Black Box: The

Knowledge Transformation Cycle. Management

Science, 49(9), 1180-1195.

Chermack, T. J., 2004. Improving Decision-Making with

Scenario Planning. Futures, 36, 295-309

Chermack, T. J., van der Merwe, L., 2003. The role of

constructivist learning in scenario planning. Futures,

35, 445-460.

Cook, S. D. N., Brown, J. S., 1999. Bridging

Epistemologies: The Generative Dance Between

Organizational Knowledge and Organizational

Knowing. Organization Science, 10(4), 381-400.

Emery, J. C. 1969. Organizational Planning and Control

Systems, Theory and Technology, Macmillan

Publishing Co. Inc. New York, NY.

Fjermestad, J., Hiltz, S. R., 2001. Group Support Systems:

A Descriptive Evaluation of Case and Field Studies.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 17(3),

115-159.

Gammelgaard, J., Ritter, T., 2008. Virtual Communities of

Practice: A Mechanism for Efficient Knowledge

Retrieval in MNCs. International Journal of

Knowledge Management, 4(2), 46-51.

Jennex, M. E., Olfman, L., 2006. A Model of Knowledge

Management Success. International Journal of

Knowledge Management, 2(3), 51-68.

Kahn H., Wiener, A. J., 1967. The Year 2000: A

Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three

Years, Collier-Macmillan Ltd. London, UK.

Kimble, C., Hildred, P., Wright, P., 2001. Communities of

Practice: Going Virtual. In Malhotra, Y. Knowledge

Management and Business Model Innovation, 220-

234, Idea Group Inc. Hershey, PA.

Kivijärvi, H. 2008. Aligning Knowledge and Business

Strategies within an Artificial Ba. In El-Sayed Abou-

Zeid ed. Knowledge Management and Business

Strategies: Theoretical Frameworks and Empirical

Research

, Idea Group Inc. Hershey, PA.

Kivijärvi, H., Piirainen, K., Tuominen, M.,. Elfvengren,

K., Kortelainen, S., 2008. A Support System for the

Strategic Scenario Process. In Adam, F., Humphreys,

P. eds. Encyclopedia of Decision Making and

Decision Support Technologies, Idea Group Inc.

Hershey, PA.

Lave, J., Wenger, E., 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate

peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

New York, NY.

Lesser, E., Everest, K., 2001. Using Communities of

Practice to manage Intellectual Capital. Ivey Business

Journal, March/April.

Leonard, D., Sensiper, S., 1998. The Role of Tacit

Knowledge in Group Innovation. California

Management Review, 40(3), 112-132.

Lindqvist, A., Piirainen, K.., Tuominen, M., 2008.

Utilising group innovation to enhance business

foresight for capital-intensive manufacturing

industries. In the Proceedings of the 1st ISPIM

Innovation Symposium, Singapore.

Nunamaker, J. F. Jr., Briggs, R. O., Mittleman D. D.,

Vogel, D. R., Balthazard, P. A., 1997. Lessons from a

Dozen Years of Group Support Systems Research: A

Discussion of Lab and Field Findings. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 13(3), 163-207.

Piirainen, K., Tuominen, M., Elfvengren, K., Kortelainen,

S., Niemistö, V.-P., 2007. Developing Support for

Scenario Process: A Scenario Study on Lappeenranta

University of Technology from 2006 to 2016, Research

report, no. 182, Lappeenranta University of

Technology. Lappeenranta, FI. Available at:

http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-214-369-3

Piirainen K., Kortelainen S., Elfvengren K., Tuominen M.,

2010. A scenario approach for assessing new business

concepts. Management Research News, 32(7) – in

press

Polanyi, M., 1962. Personal Knowledge, University of the

Chicago Press. Chicago, IL.

Polanyi, M., 1966. The Tacit Dimension, Doubleday &

Company Inc., Reprinted Peter Smith. Gloucester,

MA.

Schwartz, P., 1996. The Art of the Long View: Planning

for the Future in an Uncertain World, Doubleday Dell

Publishing Inc. New York, NY.

Simon, H. A., 1960. The New Science of Management

Decisions, Harper Brothers. New York, NY.

Swan, J., Scarborough, H., Robertson, M., 2002. The

Construction of `Communities of Practice' in the

Management of Innovation. Management Learning,

33(4), 477-496.

Tsoukas, H., Vladimirou, E., 2001. What is Organizational

Knowledge? Journal of Management Studies, 38(7),

973-993.

Zeleny, M., 2005. Human Systems Management:

Integrating Knowledge, Management and Systems,

World Scientific Publishing.

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

54