COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE AND THE CHALLENGE OF

MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

Eric Bun, Pieter de Vries

Verdonck, Klooster and Associates, Delft University of Technology

Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Department of Systems Engineering, The Netherlands

Gwendolyn Kolfschoten, Wim Veen

Delft University of Technology - Faculty of Technology

Policy and Management, Department of Systems Engineering, The Netherlands

Keywords: Communities of Practice, Management Paradox, Management Support, Support Tool, Case Study.

Abstract: Communities of Practice (CoP) are a strategic asset for innovative organisations. However, managers have

problems to manage and facilitate CoPs, and therewith to harvest the benefits of these communities for the

organisation. The goal of this research is to supply managers with a support framework to facilitate the

development of CoPs, the CoP activities, and their contribution to the organisation. A design science study

is conducted, which comprises of a literature research to develop a knowledge base and a study of cases to

develop an environment base. Combined these sources are used to create a support tool, which was then

evaluated by an expert panel.

1 INTRODUCTION

A community of practice (CoP) offers participants a

social platform to develop, share, store and elaborate

on knowledge in an effective way. CoPs generate

innovative products and services and therefore

contribute to organisational performance. While

CoPs mostly spontaneously emerge, managers

generally feel the urge to support and encourage the

development and activities of CoPs in order to create

an innovative climate in the organisation. However,

management involvement is likely to suffer from the

management paradox; as traditional management

strategies tend to conflict with the core values of a

CoP (Wenger and Snyder, 2000).

Using design science as a research approach, we

present a tool to support the management and

facilitation of CoPs. To this end, findings of a case

study at an international consultancy firm will be

presented in combination with a literature study on

CoP evolvement.

First, the literature study focused on several CoP

evolvement models. The model of Gongla and

Rizzuto (2001) is used as a basis for a general notion

on CoP management and extended with additional

practices from (e.g Wenger and McDermott, 2002;

Brown and Duguid, 1991; Sunassee and Sewry,

2002 and Tremblay, 2004). The extended model is

further used to structure this paper.

Second, interviews and an expert panel were

used to identify and validate additional promising

practices on CoP management. Both the literature

and the lessons learned were then used to develop a

tool that can serve as a support framework for CoPs

in different phases of their lifecycle.

The support framework for managing CoPs

presented in this paper offers new insights for both

business managers and scientists. For managers, the

paper offers a set of guidelines from literature and

practice, which can be used in their daily

considerations regarding CoP support. For research

the paper offers a framework for the facilitation and

management of CoPs that can be used for further

research on the use of CoPs to improve the

innovative capacity of organisations. Such a

framework can be used to:

1. Gain insight in what management interventions

to use in which context to support CoPs

2. Develop best practices and techniques to support

CoPs in creating innovative solutions for an

186

Bun E., Vries P., Kolfschoten G. and Veen W. (2009).

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE AND THE CHALLENGE OF MANAGEMENT SUPPORT.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, pages 186-193

DOI: 10.5220/0002305801860193

Copyright

c

SciTePress

organisation

3. Further develop tools to support the activities of

CoPs and to further harvest their value for the

organisation.

The focus in this study is on issue one. Further

research is needed to deal with the other issues

moving towards a framework that helps to decide

about the productivity of these CoPs for the

organisation.

2 COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

The ‘Community of Practice-concept’ is an

approach to generate knowledge by means of social

interactions in a human network. In principle, CoPs

have been used for centuries, but the concept has

only recently been labelled (Lave and Wenger,

1991). Within this research the following definition

is used (Wenger et al, 2002):

“Communities of Practice are groups of people

who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion

about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and

expertise in this area through interaction at an

ongoing basis”

There are four main types of CoPs (Vestal, 2003):

1. Innovation community; cross-functional in

nature, works together to figure out new

solutions through the knowledge they already

have.

2. Helping community; focuses on helping people.

3. Best-practice community; concerned with

attaining, validating and disseminating

information.

4. Knowledge-stewarding community; focuses on

connecting people and connecting and

organizing information and knowledge across

the organisation.

2.1 Management of CoPs

For CoPs to be effective participants need to have a

shared interest, form a community and exchange

knowledge within the community on a regular basis.

CoP members thus need to have time and means to

communicate with one another. Since shared interest

is all that is needed to join a CoP, CoPs are

considered different from traditional team work

approaches (Bryan et al, 2004) and comprise

different features including variety, identity,

significance, autonomy and feedback (Bryan et al,

2004).

We can look at management interventions to

cultivate and support CoPs in their activities on three

different levels; Strategic, Tactical and Operational.

In this paper we will focus on the way business

managers have a direct influence on the in- and

output of community processes on the tactical level

by providing, for instance, (financial) rewards, time

and resources. The tactical level is the most

appropriate to influence an organisation’s

management style to improve CoPs support.

Management involvement on the three levels must

be aligned with the stages of development of a CoP

to correspond with for instance the stage of mutual

trust and openness between members, the level of

energy within the CoP and the maturity of

supporting tools and methods.

2.2 CoP Evolvement within

Organisations

CoPs do not simply emerge; they grow, split up,

grow further, evolve and might eventually die.

There are three evolvement theories: the evolution

model of Gongla and Rizzuto (2001), the life-cycle

model of Wenger (1998) and the life-cycle model of

McDermott (2000).

The research elaborates on the model proposed

by Gongla and Rizzuto (2001), because their model

is founded on many case studies and extensively

discusses organisational involvement in the different

stages of development. CoPs evolvement can be

described in five stages (2001):

1. Potential stage; individuals find out that they

have something in common and group in order

to gain insights in the benefits of a community.

2. Building stage; the community defines itself

further, creates an identity and etiquette.

3. Engaged stage; all internal processes are now

aligned to a common purpose.

4. Active stage; communities’ value becomes

essential to engaged participants and the

nurturing organisation.

5. Adaptive stage; the community starts to adapt to

changing environments and deploys new

communities themselves.

Tarmizi and Vreede (2005) integrate these stages

with the evolution models of Wenger (1998) and

McDermott (2000). Gongla and Rizzuto’s (2001)

model differs in stage 4 and 5 because they consider

CoPs’ level of energy and visibility to grow even

further. At the same time this development model

envisages the possibility that CoPs could suddenly

fall apart after each stage. To gain insights in the

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE AND THE CHALLENGE OF MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

187

type of management support to use in what context,

it is preferable to use a descriptive model with

limited stages. In other words, stages that could

either end or continue as being described by Gongla

and Rizzuto (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A visual representation of the different

evolvement models.

In this paper the adaptive stage 5 will not be

considered, because Gongla and Rizzuto (2001)

consider a community in the adaptive stage as part

of the existing organisational processes. In fact,

CoPs in this stage become totally self-organising and

self-supporting and they might even create charters

for new communities (Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001).

Therefore discussing organisational or management

requirements for this stage is not very useful for the

scope case of this paper.

2.3 The Management Paradox in

Support of CoPs

Deploying and managing CoPs in the context of

existing business processes is likely to result in the

management paradox (based on Wenger and Snyder,

2000):

Business managers are able to cultivate cops by

providing the right support (e.g. financial support,

resources, knowledge), but managers could rather

easily destroy the value of communities by imposing

too much or applying counter productive

management efforts. Managers are used to carry out

‘classical’ management strategies which do not

seem to fit these very personal, collaborative,

informal and spontaneous working formats

(processes).

Moreover, the management paradox describes

the conflicts resulting from management efforts to

stimulate performance and productivity on the one

hand and the community core values and

spontaneous developing nature on the other hand.

Classical management styles do not seem to fit new

organisational formats, such as CoPs. Consequently,

the organisations’ ability to actively facilitate and

support the development of such communities

remains uncertain (Thompson, 2005).

3 RESEARCH APPROACH

The goal of this study was to increase our

knowledge on the management issue while

developing a tool to support CoPs development.

This design science approach proposes design as a

research strategy to gain knowledge and

understanding about the object under construction.

Design science can be used to research not just

instantiations (prototypes or systems) but also

models (frameworks and representations) and

methods (algorithms and practices) (Hevner et al,

2004). Design science advocates learning from a

knowledge base and an environment base to

establish rigor and relevance in a design effort with

the intention to create new insights and

understanding through design, and the evaluation of

design (Hevner et al, 2004).

In this study, the object of design is a ‘support

tool’, a framework in which techniques to support

CoP development are captured. Such a framework

helps to address the problem of a management

paradox with respect to CoPs. The research

contribution of this paper is therefore to present an

overview of effective management support

interventions, linked to the different development

phases and organisational levels in the CoP’s life

cycle.

4 GUIDELINES FROM THE

LITERATURE

Various search engines and a snowball method was

used to gather information on guidelines for the

management support of CoPs that form the

knowledge base of this design study. In this section,

the tactical practices identified in the literature are

ordered along the five stages of a CoP’s lifecycle.

Furthermore we added some generic guidelines for

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

188

CoP management on the strategic and operational

level.

4.1 Level 1: Strategic

From a strategic perspective it is of great importance

that an organisation considers itself as a community-

of-communities symbolized as a pile of intertwined

communities (Brown and Duguid, 1991). In other

words, an organisation should accept that they way

people actually work differs fundamentally from the

ways this is described by the organisation in

manuals, programs, charts and others (Brown and

Duguid, 1991). Therefore, knowledge management

should be approached from a community perspective

that connects to corresponding working practices. .

4.2 Level 2: Tactical

In this research we focussed on the tactical level,

because the management paradox is likely to

manifest itself predominantly on this level. A

selected set of the most important success factors are

described here.

Stage 1: Potential Stage

First, a manager should engage an “energiser”, a

person who actively helps to locate and link

individuals. An energiser within an organisation

should identify existing informal groups and

uncover cross-departmental challenges or problems

(Wenger et al, 2002). The appointed ‘energiser’

should have the skills to lower the thresholds for

networking. “Human intermediaries can be quite

valuable in helping connect individuals to other

community members” (Lesser and Storck, 2001:

84).

Second, managers should lower the threshold for

networking by encouraging and supporting face-to-

face events (Tremblay, 2004), common education

and development processes (Gongla and Rizzuto,

2001), corporate universities, libraries, sporting and

diner activities (Wenger, 1998).

Stage 2: Building Stage

In the building stage, managers should consider

whether or not they want to support a community. If

they decide to, they can carry out several

management practices in this stage.

First, a rather trivial management practice is the

provision of time to participate in CoPs (Wenger et

al, 2002). Because community involvement should

not be jeopardized by working activities, people

should feel that they have some time available to

steward a forming community. However, when

business managers provide time, they usually want

to assess the value of a community. Managers

should use non-traditional methods to measure

value, by for instance, listening to members’ stories.

Members’ stories clarify the complex relationships

among activities, knowledge and performance

(Wenger et al, 2002). The non-traditional methods

should be integrated in existing performance

assessment arrangements. People that contribute to

knowledge management initiatives should be

rewarded (Sunassee and Sewry, 2002).

Second, managers can help to define the scope

and type of the memberships and determine ways in

which to identify, attract, or recruit new members

(Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001).

Stage 3: Engaged Stage

In this stage, a community should focus or expand.

Success factors are related to the inner relationships

between community members.

Because a community at this stage becomes

important for the nurturing organisation, managers

should set up regular interactions wherein they keep

track of the activities and outcomes of a community

(Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001). However, a business

manager should acknowledge the values of a

community and could only attempt to redefine

scope, mission or mode of operation, or support

growth (Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001).

Furthermore, in this stage, it becomes important

that communities’ effectiveness is measured and

reflected to community participants. It enables them

“to learn about themselves and improve internal

operations” (Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001: 851).

Stage 4: Active Stage

A community that arrives at this stage needs

management that really coordinates multiple work

groups and teams (Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001).

Business managers should integrate feedback

mechanisms with organisational processes and

report needs. In this way, the essential self-learning

activities of a CoP could be further enhanced

(Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001).

4.3 Level 3: Operational

Tools should be flexible and customisable (Simons,

2000). Tools will be used for both directive (e.g.

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE AND THE CHALLENGE OF MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

189

chat, phone calls and virtual meetings) and

nondirective (electronic messaging systems, forums

and) collaboration (Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001) and

knowledge organisation (e.g. collaborative tagging)

(Macgregor and McCulloch, 2006). The last

important functionality of tools should be the

support of Social Network Analysis (SNA), which is

valuable for both managers as well as participants to

uncover interpersonal relationships and potential

CoPs (Cross et al, 2004).

5 CASE STUDY

In addition to the knowledge base the environment

and context in which CoPs evolve was analyzed. For

this purpose a case study was carried out at a large

international IT consultancy firm. Eight semi-

structured interviews were conducted with four

business managers and four CoP participants on how

the consultancy firm manages CoPs in practice. The

aim of the semi-structured interviews was to obtain a

rather holistic view on the way the IT consultancy

firm dealt with CoPs and therefore both managers

and CoP participants were engaged.

Moreover an expert panel session was conducted

in a Group Decision Room (GDR). A GDR provides

electronic meeting facilities and yields additional

benefits over other workshop formats, such as

parallel and autonomous brainstorming, automatic

generated reports and quick results. Two business

managers, four CoP participants and two CoP

experts participated in the expert panel which lasted

four hours. The aim of the panel was twofold:

validating the results of the interviews and

brainstorming on new practices.

Practices were validated by raising statements

which were ranked by the participants. They could

indicate to what extent the statements hold true in

their daily business and community face-off.

Correspondingly, promising tactical management

practices were uncovered by utilising the free format

brainstorming techniques covered in the GDR.

Participants could raise new practices anonymously

which were ranked and prioritised by the group

accordingly.

From the case study, we can conclude and

confirm the following guidelines on a tactical level:

Appoint ‘Energisers’ (e.g. highly dedicated and

passionate CoP evangelists) in each

department;

Asses individual employees on how they share

their knowledge throughout the company and

provide rewards (e.g. knowledge sharing

award’);

Lower the thresholds to constitute CoPs; make

resources widely and easily available for CoP

support ;

Obligate employees to store ‘lessons learned’

after each project has been finished;

Utilise ‘intervision’ (exchanging perspectives

and lessons learned about a practice or role) as

a problem solving technique, instruct managers

on how to use it and focus on the autonomy of

the professional;

Empower employees; design an environment

where people are able to steward the

evolvement of the community.

The utmost important tactical management practices,

as denoted in the case study are summarised in table

1. The table categorises these general practices from

the different stakeholder perspectives.

Table 1: Summary of the major tactical management

practices from the different stakeholder perspectives.

CoP participant CoP manager Expert panel

CoP #1

Provide a new

‘channel’ to

influence

business

decision making

Influence the

emergence of a \CoP

by involving CoP

experts and potential

community members

• Appoint

energizer

• Assess

individuals

• Lower

thresholds

• Store lessons

learned

• Utilise

‘intervision’

• Empower

employees

CoP #2

Evangelise the

CoP and

encourage

potential

members to join

Provide room and

create a culture that

encourage employees

to take initiatives

CoP #3

Empower the

‘emerging

leader’ to free up

resources

Community

interaction through

the ‘emerging leader’

6 A SUPPORT TOOL TO

MANAGE AND FACILITATE

CoPS

The outcome of the literature research and the

results of the case study practices are bundled in a

‘support tool’ for CoP management that is presented

along the three levels of organisational involvement.

In line with the research scope, the tactical level of

organisational involvement is specified along the

four stages of community evolvement. The ‘tool’

consists of a framework (see figure 2) helps

managers to identify managerial interventions that

support the development and success of the CoP at

the different stages of its life cycle.

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

190

6.1 Level 1: Strategic

From a strategic level, the case study discovered the

lack of a uniform approach on CoP management at

the IT consultancy firm. Consequently, CoP support

heavily depends on the particular individual

management style of a business manager. One of the

key consequences of the reliance of an individual

management style is that some employees feel that

they have to put great efforts before they get any

support where others are actively encouraged to

attend various KM development and collaboration

programs. An external knowledge management

(KM) task force, which engage KM experts,

business managers, and various employees of the

consultancy firm, has to overcome problems raised

by developing such a uniform approach.

6.2 Level 2: Tactical

The case study resulted in several findings on how

managers at the IT consultancy firm can support

CoPs in their different stages of evolvement. The

practices uncovered in the interviews and expert

panel add up to the practices denoted in the literature

(section 3).

Stage 1: Potential Stage

In order to link potential community members,

business managers could assume two different

approaches on CoP management. In the first place,

business managers carry out ‘general’ practices

which support on their own accord emerging CoPs

by making, for instance, ‘account-meetings’ more

accessible so employees get a better understanding

of the company’s main concerns.

In the second place, managers take the lead by

making an attempt to link potential community

members before any community has been formed.

One successful CoP at the IT consultancy firm was,

in fact, planned by a manager. He engaged potential

members, experienced KM experts and encouraged

members to form a community. However, the way

the CoP subsequently emerged was barely

influenced by the manager.

Stage 2: Building Stage

Managers can influence CoP building by

encouraging employees to store ‘lessons learned’.

Storing lessons learned helps to activate the reuse of

knowledge in later projects. Therefore, by

committing employees to store their lessons learned,

reuse of their knowledge is likely to improve the

knowledge level in similar or related projects.

The idea of engaging ‘energisers’ was well

conceived in the interviews and expert-panel. At the

IT consultancy firm, energisers could overcome

organisational structures by encouraging

collaboration between departments in mini KM task

forces.

Lastly, business managers should be instructed

(by the KM task force) on how to further encourage

CoP building. Managers should utilise intervision as

a method to solve problems thoroughly. Briefly,

intervision is a problem solving technique in which

participants discuss about the context of a problem

and not about the solutions. Intervision enhances

self-reflection and collective capability development

and can therefore encourage CoP forming.

Stage 3: Engaged Stage

In the engaged stage, both managers and CoP

participants have knowledge about how community

effectiveness could be measured. In this stage, a

knowledge-sharing award could further help to

emphasise the importance of knowledge sharing.

Business managers should acknowledge and

eventually reward individuals on the extent they

share their knowledge throughout the company.

Second, because community’s value becomes

more visible, managers should also be assessed on

how their team shares its knowledge throughout the

company. This is of main importance in order to

stimulate cross-departmental knowledge sharing.

Stage 4: Active Stage

The management constituted successful CoP

reemphasised the practices found in the literature

including the need for management to integrate

feedback mechanisms with organisational processes

and report needs. In order to do so, the particular

manager intertwined community outcomes in

strategic decision processes. Members indeed

experienced this as a way to improve self-learning

activities when their community outcomes where

reflected in strategic decisions. Besides the

confirmation of this management practice, no

additional practices were uncovered for this stage.

6.3 Level 3: Operational

On an operational level, a few promising practices

were discovered. First, employees denoted the need

for visualising existing (tacit) knowledge maps in

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE AND THE CHALLENGE OF MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

191

order to be able to search for knowledge instead of

information. Therefore, Social Network Analysis

(SNA) functionalities should be extended with a

voting systems.

Second, tools should provide opportunities to

store and utilise lessons learned in an effective way.

6.4 The Support Tool

The objective of the study was to gain insight in

what management interventions to use and in which

context to support CoPs. This is the first issue in a

prospective management support framework that

eventually should deal with the productivity of CoPs

for the organisation. The outcome of this research is

a conceptual management support tool for CoP on

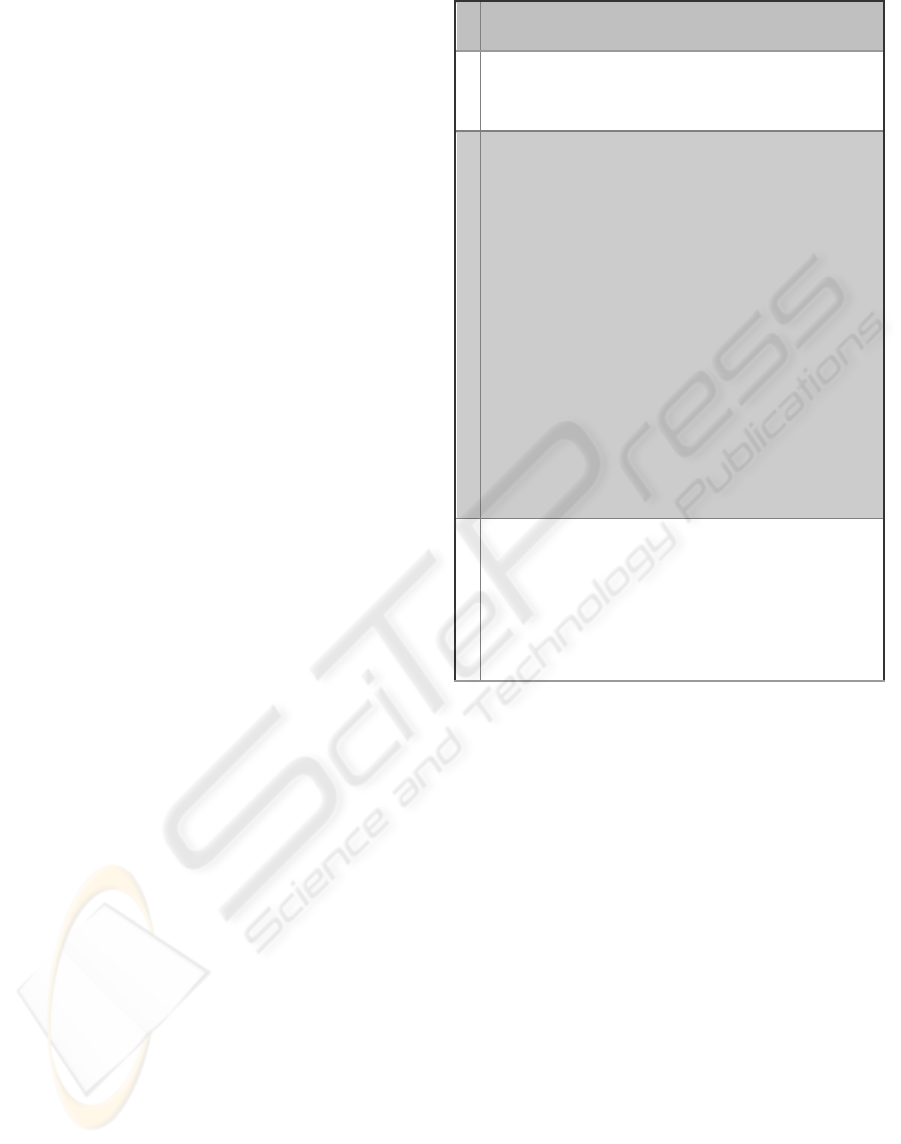

primarily the tactical level. Figure 2 provides an

overview of the practices identified in the literature,

interviews and expert panel. The practices indicated

with ‘new’ were uncovered in the case study.

The support tool provides management guidance

on a tactical level per evolvement stage. However,

CoP support cannot be limited to the static context

of stages. The growth of CoPs through the stages is

required as well and managing this transition

between the stages is therefore of great importance.

The case study found three major influence areas to

guide a CoP through the transition of stages:

1. Roles and responsibilities; when communities

evolve the role of the community initiator can

move from a rather directing to a more

facilitating role. Managers can support in the

transition with coaching members and

uncovering lessons learned from former

communities.

2. Funding and sponsorship; an evolving

community needs (financial) support. Managers

can support in the transition by providing time,

money and freeing up resources.

3. Awareness and visibility; a community needs

interaction with the environment to grow and

evolve. Therefore, managers can support a

transition by promoting CoPs in and outside the

organisation.

A seamless intertwinement of the management

support tool and transition management is essential

for the first issue in a prospective management

support framework.

Stage 1:

Potential

stage

Stage 2: Building stage Stage 3:

Engaged stage

Stage 4:

Active stage

Strategic

Organisation as a community-of-communities

Engage an external KM task force (new)

Reserve a central KM budget (new)

Tactical

•

Engage

“energisers

”

• Stimulate

common

activities

• Stimulate

face-to-

face

meetings

• Allow

natural

community

forming

• Make

‘account-

meetings’

more

accessible

(new)

•

Provide time

• Use non-traditional

methods to measure

value

• Help to plan growth

and operation

• Obligate employees to

store ‘lessons learned’

(new)

• Engage mini task

forces over divisional

boundaries in order to

share knowledge

between departments

(new)

• Make managers and

employees familiar

with ‘intervision

creation’ (new)

• Try to be

engaged in

community’s

processes to

keep on track

• Measure

effectiveness

• Promote self-

learning

• Introduce a

knowledge-

sharing award

(new)

• Assess

business

managers on

how their team

share their

knowledge

(new)

• Integrate

community

feedback

loops with

organisation

al processes

and reports

Operational

Implement easy portals

Directive and non-directive collaboration tools

Utilise tools that enable sharing tacit knowledge

Deploy customisable tools & methods

Utilise Social Network Analysis

Support self-learning activities by tools and methods

Visualise (tacit) knowledge maps (new)

Develop methods & tools to store ‘lessons learned’ (new)

Figure 2: A support tool for managing CoPs.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The goal of this research was to develop a support

tool for managers in facilitating the development of

CoPs. Along the community evolution model of

Gongla and Rizzuto, guidelines from the literature

were added with promising practices from our

knowledge and environment base. The practices

were subsequently evaluated by an expert panel.

Based on the results, a support tool for managing

CoPs was built.

The research is based on a study of several cases

at (or linked to) the large international IT

consultancy firm which makes it on the one hand

extensive, profound and detailed but on the other

hand the research could be extended by more case

studies at other business and in other industries.

Further research should therefore focus on the

management paradox and management practices in

other industries in order to extend this first

framework for management support. Besides the

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

192

transition management concept needs more

elaboration on how to flow through the stages. In

other words, how to select the most appropriate

practices in which stage and context to catalyse the

emergence of a CoP.

Another important area for further research is the

measurement of the effectiveness of different

management styles on CoPs, and the measurement

of CoP’s successfulness in general. Such metrics can

be based on research on knowledge management

effectiveness related to management styles. The

Knowledge Governance Framework might be a

good starting point in this respect (Smits and Moor,

2005). However, the success and impact of CoPs

will remain difficult to measure and assess,

consequently making them vulnerable for the

management paradox. Solving this issue will

therefore require a way to better assess the impact of

CoPs on knowledge activation and use in the

organisation. The more explicit the value of CoPs

the easier it will be to avoid the management

paradox and facilitate the cultivation of CoPs.

REFERENCES

Brown, J.S., Duguid, P., 1991. Organizational Learning

and Communities of Practice: Toward a Unified View

of Working, Learning, and Innovation, Organization

Science 2 (1), pp. 40-57.

Bryan, L., Steve, C., Elayne, C. and Gillian, J., 2004.

Beyond Knowledge Management. Idea Group

Publishing.

Cross, R., Borgatti, S.P., Parker, A., 2004. Making

Invisible Work Visible: Using Social Network

Analysis to Support Strategic Collaboration, Creating

Value with Knowledge, January (22), pp. 82-103.

Hevner, A., March, S., Park, J., and Rahm, S., 2004.

Design Science Research in Information Systems.

Management Information Systems Quarterly, 28, 1,

75-105.

Gongla, P., Rizzuto, C.R., 2001. Evolving Communities of

Practice: IBM Global Services experience, IBM

Systems Journal 40 (4), IBM, California, pp. 842-862.

Lave, J., Wenger, E.C., 1991. Situated Learning:

Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Lesser, E.L, Storck, J., 2001. Communities of practice and

organizational performance, IBM Systems Journal 40

(4), 831-841.

Macgregor, G., McCulloch, E., 2006. Collaborative

tagging as a knowledge organisation and resource

discovery tool. Library review 55 (5), pp. 291 – 300.

McDermott, R., 2000. Community Development as a

Natural Step: Five Stages of Community

Development, KM Review 3 (5), pp. 16-19.

Simons, P.R.J., Admiraal, W., Akkerman, S., Groep J. and

Laat, M. D., 2000. How people in virtual groups and

communities (fail to) interact, The biannual

conference of the European Association for Research

on Learning and Instruction, August 26-31, Padua,

Italy, Centre for ICT in Education, Utrecht University.

Smits, M., Moor, A., 2005. Measuring Knowledge

Management Effectiveness in Communities of

Practice, Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences number 37.

Sunassee, N., Sewry, D., 2002. A Theoretical Framework

for Knowledge Management, Proceedings of SAICSIT.

Tarmizi, H., Vreede, G.J., 2005. A facilitation Task

Taxonomy for Communities of Practice, Eleventh

Americas Conference on Information Systems, Omaha,

August 11th – 14th.

Tremblay, D.G., 2004. Communities of Practice: Are the

conditions for implementation the same as for a virtual

multi organisation community, Canada research chair

on the socio economic challenges of the knowledge

economy, Université du Québec.

Vestal, W., 2003. Ten Traits for a Succesful Community

of Practice. Knowledge Management Review,

January/February (5).

Wenger, E.C., 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning as

a social system, Systems Thinker 9 (5), pp. 2-3.

Wenger, E.C., Snyder, W.M., 2000. Communities of

Practice: The Organizational Frontier, Harvard

Business Review, January/February, pp. 139-145.

Wenger, E.C., McDermott, R., Snyder, W.M., 2002.

Cultivating Communities of Practice, Harvard

Business School Press, Boston.

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE AND THE CHALLENGE OF MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

193