ONTOTERMINOLOGY

A New Paradigm for Terminology

Christophe Roche

1

, Marie Calberg-Challot

2

, Luc Damas

1

and Philippe Rouard

3

1

Condillac “Knowledge Engineering” Research Group – LISTIC Lab.

University of Savoie – Campus Scientifique, F – 73 376 Le Bourget du Lac cedex, France

2

Ontologos corp. P.A.E. du Levray, 6 Route de Nanfray, F – 74960 Cran Gevrier, France

3

EDF CIH, Bâtiment Euclide, Savoie Technolac, F – 73373 Le Bourget du Lac cedex, France

Keywords: Ontology, Terminology, Ontoterminology, Knowledge representation, Term definition, Concept definition,

Hyper schema.

Abstract: Today, collaboration and the exchange of information are increasing steadily and players need to agree on

the meaning of words. The first task is therefore to define the domain’s terminology. However, terminology

building remains a demanding and time-consuming task, even in specialised domains where standards

already exist. While reaching a consensus on the definition of terms written in natural language remains

difficult, we have observed that in specialised technical domains, experts agree on the domain

conceptualisation when it is defined in a formal language. Based on this observation, we have introduced a

new paradigm for terminology called ontoterminology. The main idea is to separate the linguistic dimension

from the conceptual dimension of terminology and establish relationships between them. The linguistic

component consists of terms (both normalised and non-normalised specialised words) linked by linguistic

relationships such as hyponymy and synonymy. The term definition, written in natural-language, is

considered a linguistic explanation. The conceptual component is a formal ontology whose concepts are

linked by conceptual relationships like the is-a (kind of) and part-of relations. The concept definition,

written in a formal language, is viewed as logical specification. An ontoterminology enables us to link these

two non-isomorphic networks in a global and coherent system.

1 INTRODUCTION

Building terminology is a demanding and expensive

task. Writing definitions taking into account the

different meanings remains difficult, even in

technical domains where standards already exist.

We have observed that although experts share

the same domain conceptualisation, they do not

necessarily agree on the definition of terms when

written in natural language – we should bear in mind

that from the terminology point of view, a term is a

“specialised linguistic unit” which denotes a concept

of the domain called the meaning of the term. We

have also observed that each time communication

problems occur experts refer mainly to technical

diagrams or formulas rather than texts or standards.

In fact, experts agree on concept definitions when

they are written in a formal (logical) or semi-formal

(e.g. conceptual graph) language. These definitions

are objective since their interpretation is ruled by a

formal system.

The main contribution of this article is to claim

that in terminology (especially for technical

domains), terms i.e. the “verbal definition of a

concept” (ISO 1087) need to be separated from

concept names since they belong to two different

semiotic systems. The first is a linguistic system

while the second is conceptual. Similarly, term

definitions written in natural language need to be

separated from concept definitions written in a

formal language. The former are viewed as linguistic

explanations while the latter are considered logical

specifications of concept. The result is a new kind

of terminology called ontoterminology (since the

meaning of terms relies on a formal ontology) which

brings these two non-isomorphic systems together

into a coherent, global one.

321

Roche C., Calberg-Challot M., Damas L. and Rouard P. (2009).

ONTOTERMINOLOGY - A New Paradigm for Terminology.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development, pages 321-326

DOI: 10.5220/0002330803210326

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 ONTOTERMINOLOGY

Separating the linguistic dimension of terminology

from its conceptual dimension has led us to

introducing a new paradigm for terminology called

ontoterminology. This implies that terms should be

separated from concepts as well as term definitions

from concept definitions.

Although in the General Theory of Terminology

the meaning of a term is a concept, the main goal of

terminology is not to represent concepts in order to

manipulate them (as in artificial intelligence) but to

define a common vocabulary we hope is consensual.

The concept in terminology does not exist in itself. It

exists through the definition of the term written in

natural language.

On the other hand, conceptualisation is the

central issue in specialised domains. It is built

according to a given theory using a formal (or semi-

formal) language following the epistemological

principles of formal language. This means that

conceptualisation does not belong to natural

language. The logical specification of the concept is

identified to the concept itself on which experts

agree and to which they refer when ambiguities

occur. From this point of view, one could say that

the definition of the term paraphrases the formal

definition of the concept denoted by the term. The

definition of the term written in natural language is

then a linguistic explanation of the concept which

also describes the linguistic usage of the term.

Conceptualisation is the concern of knowledge

engineering. It is for this reason that we claim that

ontology (Staab et al. 2004), (Gomez-Perez et al.

2004), (Roche 2003) represents one of the most

promising ways forward for terminology. In point of

fact, ontology and terminology share the same goal:

“An [explicit] ontology may take a variety of forms,

but necessarily it will include a vocabulary of terms

and some specification of their meaning (i.e.

definitions)” (Ushold et al. 1996). Nevertheless, we

have to bear in mind that an ontology, defined as a

“specification of a conceptualisation”, is primarily

“a description (like a formal specification of a

program) of the concepts and relationships that can

exist” (Gruber et al. 1993). Therefore, an ontology is

not a terminology. The linguistic dimension of

terminology, sometimes confused with the LSP

(language for special purpose) lexicon, has to be

taken into account. Terms can not be reduced to

arbitrary words or labels stuck onto concepts. Terms

of usage, normalised terms, lexical forms (including

terminological variations and reductions, rhetorical

figures like ellipsis, etc.) as well as linguistic

relationships are central features in terminology.

2.1 Saying is Not Modelling

Terminology relies on two kinds of related but

separate systems. The linguistic system is directly

linked to specialised speech and text while the

conceptual system is the concern of domain

modelling. Writing specialised text is different from

conceptualisation. Even if one can extract some

useful information from text (Buitelaar et al. 2005),

(Daille et al. 2004), saying is not modelling (Roche

2007). The lexical structure (the network of terms

linked by linguistic relationships such as hyponymy

or synonymy) is not isomorphic with the conceptual

structure (the network of concepts linked by

conceptual relationships such as ‘a kind of’ or ‘part

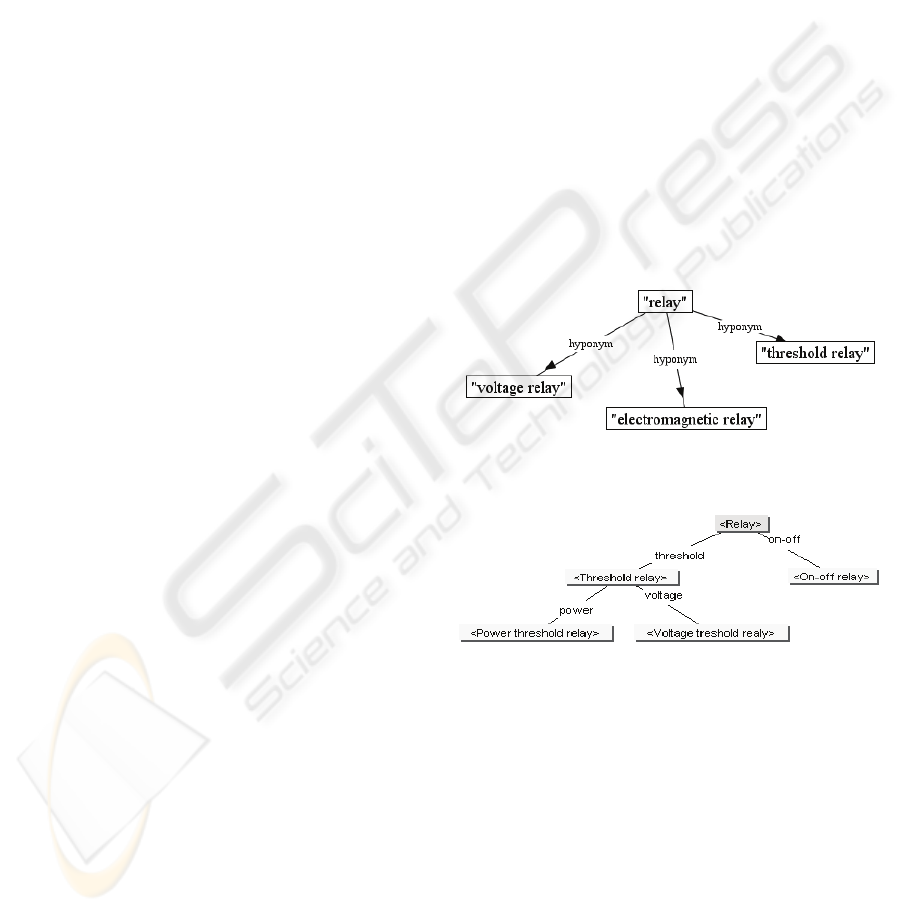

of’) as illustrated by the following simple example

(figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The lexical structure of terms.

Figure 2: The ontology of relay.

In fact we need to bear in mind that writing

documents is the concern of textual linguistics, one

of whose principles is the incompleteness of text.

Whereas building ontology, viewed as task-

independent knowledge, is the concern of modelling

based on formal (and not natural) languages. We

should also bear in mind that using rhetorical figures

like ellipsis in writing text modifies the perception

of any concepts we may have. In the previous

example (figures 1 and 2) the term “voltage relay”

does not denote a <Voltage relay> concept which

would be a sub-concept of <Relay>. It denotes the

<Voltage threshold relay> concept which is a sub-

concept of <Threshold relay>. Let us notice that the

KEOD 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

322

linguistic expression “voltage threshold relay” is not

in usage, but can be defined as a normalised term.

Although we can extract some useful information

from texts, ontology cannot be built directly from

them since we need ontology for understanding text

(understanding text requires extra-linguistic

knowledge which by definition is not included in the

corpus).

This is why we have introduced the new

paradigm of ontoterminology (Roche 2007) to take

into account these two different activities –

conceptualisation and writing text – and to focus on

conceptualisation. The main goal of terminology is

first to understand and conceptualise the world and

then to name it. Ontoterminology allows building a

new kind of terminology in which the concept plays

a central role. An ontoterminology is a terminology

whose terms, either of usage or normalised, are

related to concepts defined in a formal ontology.

This makes it possible to manage the linguistic and

conceptual dimensions of terminology and provide

two kinds of definition: the first formally defines the

concept whereas the second explains the term and its

usage from a linguistic point of view.

2.2 Term and Concept

Concepts in ontoterminology exist in their own

right. Thus, ontoterminology manages terms as well

as concepts; both are entries in this new kind of

terminology. It also means that term and concept

definitions are separate but connected since the

meaning of a term is related to a concept. In the

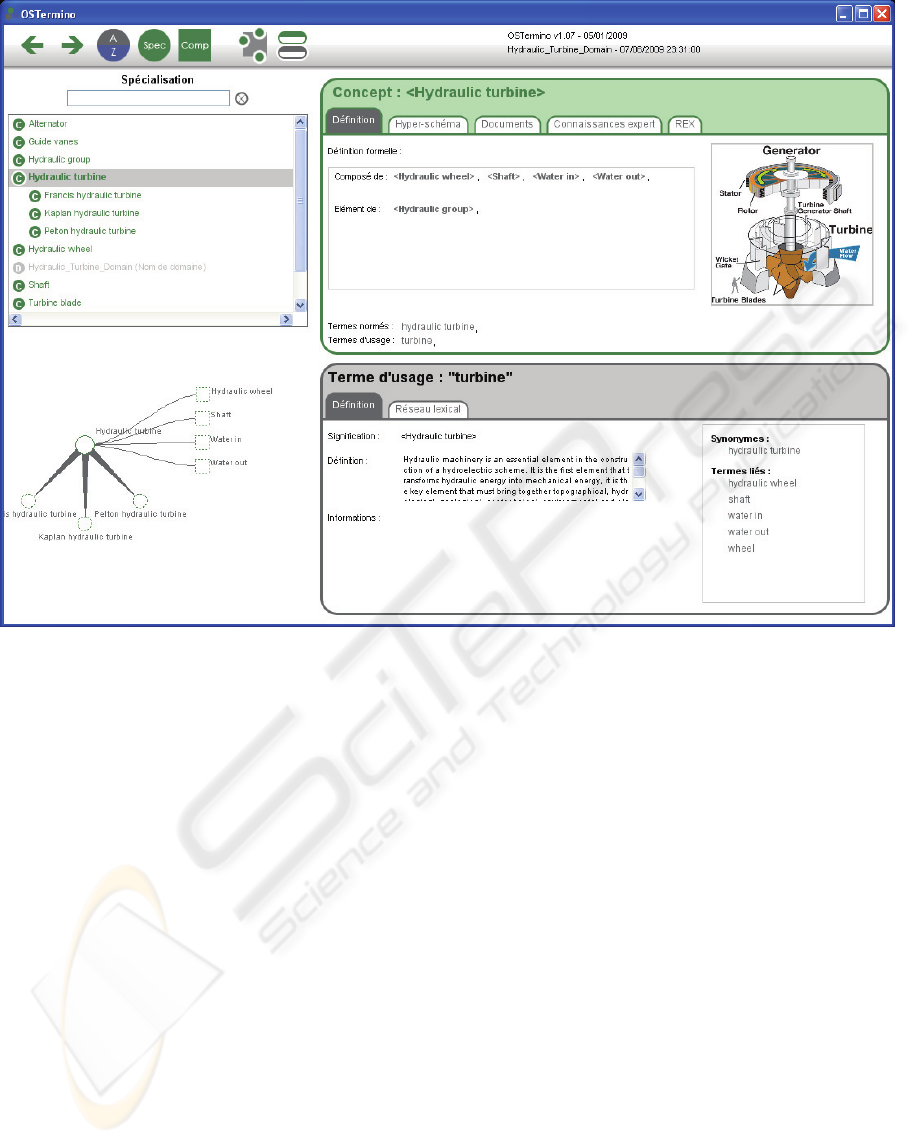

example below (see figure 3), these definitions

appear in two different cards, one for the concept

and another for the term.

Ontoterminology enables focusing on the

conceptual and linguistic dimensions of

terminology. Terms and concepts belong to different

and non-isomorphic semiotic systems. In order to

show such a difference, terms, as linguistic

expressions, are written between quotation marks

e.g. “turbine”, while concepts, as entities of a formal

system, are written between chevrons and start with

an upper case e.g. < Hydraulic turbine>.

If ontoterminology enables normalisation of

language, unlike classical terminology it also

enables preserving the diversity of language between

different communities of practice since they share

the same domain conceptualisation. In point of fact,

two different terms can denote the same concept

whose name should be written so that we understand

the right place of the concept in the ontology. Such

concept names define normalised terms which

cannot be used in text (e.g. because they are too

long) but are necessary for term meaning and

understanding. For example “voltage relay” in

English and “relais de tension” in French denote the

same concept of <Voltage threshold relay>.

2.3 Conceptual Structure

The conceptual relationships are used for structuring

entries. In figure 3 the concepts are listed in

alphabetical order combined with either the “is-a” or

the “part-of” relationship. These conceptual

relationships are also used for building the lexical

structure which is automatically updated each time

the conceptualisation is modified.

Words and linguistic relationships are no longer

the only means to access information in

terminology. Associating information to concepts,

e.g term definitions, documents, returns on

experience, etc., amounts to classifying expert

knowledge in the terminology.

It is also possible to define new paradigms of

navigation based on the domain ontology. Ontology

can be viewed as a conceptual map (Tricot et al.

2005) in which the experts navigate along the “is-a”

and “part-of” relationships in order to access

information connected to concepts (figures 3, 4 and

5).

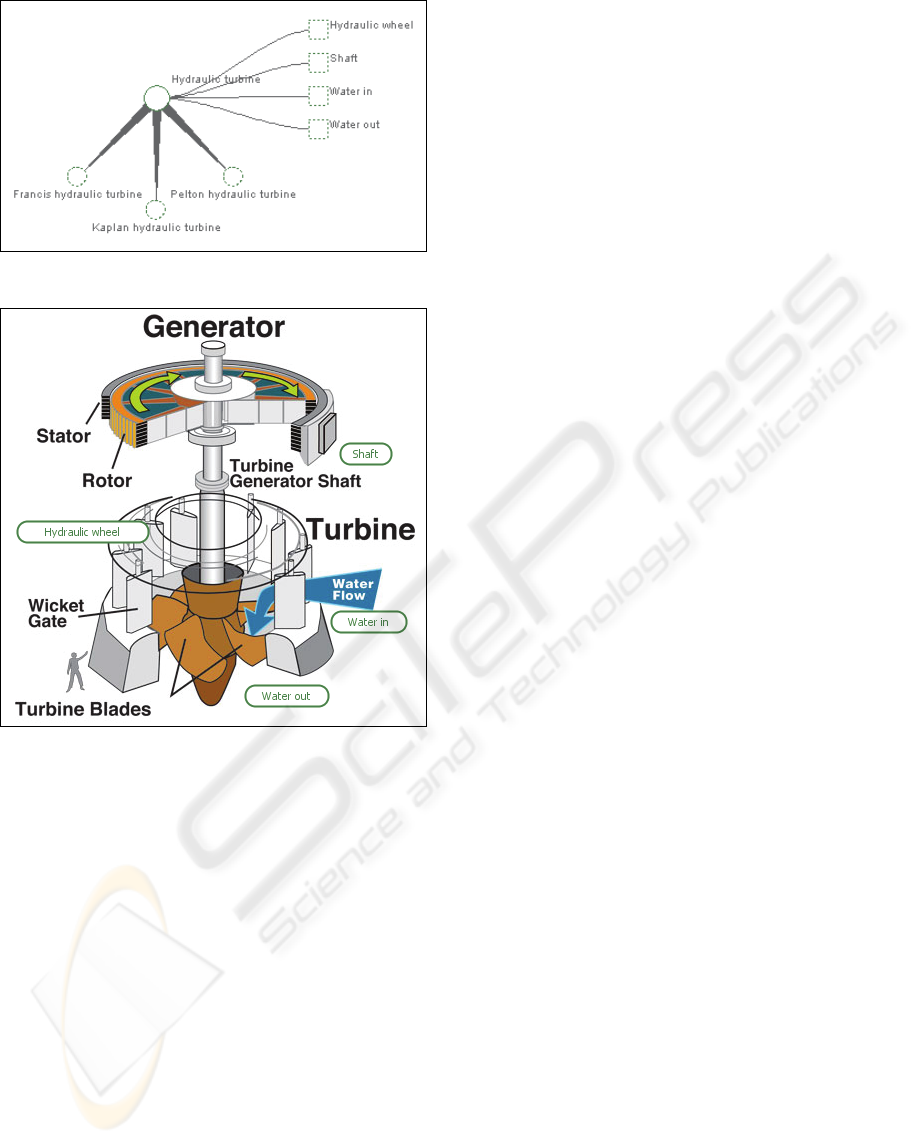

Schemas play a key role in technical domains.

From the conceptual point of view, they represent

one of the most important references. Experts agree

on this kind of independent natural language

knowledge, easier to understand and more

consensual than texts. They refer to schemas every

time a communication problem occurs or when an

explanation is required. A schema describes a

physical entity and the parts which make up it. Each

of these parts is also described by its own schema.

Entities and components are modelled by concepts

linked by the part-of relationship. These concepts

create a network of part-of linked concepts which

allows users to browse from a schema describing the

current concept to a more detailed or global schema

associated to one of its part-of concepts. Just as

hypertext has defined a new method of corpus

navigation using textual links, hyper schema defines

a new method of knowledge base navigation

attached to the domain ontology using conceptual

links (see figures 4 and 5).

ONTOTERMINOLOGY - A New Paradigm for Terminology

323

Figure 3: The ontoterminology of hydraulic turbines.

3 METHODOLOGY

Unlike textual terminology’s semasiological

approach which relies essentially on texts for

specialised vocabulary extraction (Buitelaar et al.

2005), (Daille et al. 2004), ontoterminology is based

on an onomasiological approach. It consists in first

defining the domain ontology and then identifying

the most suitable terms to denote the concepts (if

necessary, new normalised terms are proposed). Our

intention is not to compare the two approaches, their

goals remain different: the former focuses on

specialised vocabulary whereas the latter focuses on

conceptualisation. We should just bear in mind that

the lexical structure extracted from a corpus does not

match the conceptual structure directly defined by

experts using a formal language: “saying is not

modelling” (Roche 2007) (figures 1 and 2).

Building ontoterminology requires a dedicated

methodology from concept to term. Experts play a

key role for each step of the Ousia method

developed by the University of Savoie and

Ontologos corp. They began by identifying

concepts and their relationships. The result is a semi-

formal conceptual network where the part-of and is-

a relationships play a central role. This conceptual

network is defined using the SNCW tool (Semantic

Network Craft Workbench). There are few

constraints on the conceptual graph as a semi-formal

representation. It remains to formally define

concepts in an ontology. This step is performed

using the OCW environment (Ontology Craft

workbench). OCW is a software for building

ontology defined by specific differentiation (see

figure 2) (Roche 2001). The next step is to identify

the “specialised linguistic units” – which can be

extracted automatically from texts – and to define

them in natural language. The final step consists in

associating the terms with the concepts previously

defined.

KEOD 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

324

Figure 4: The conceptual structure of a turbine.

Figure 5: A hyper schema.

4 VALIDATION

Ontoterminology is currently used in different

technical domains. One of them concerns a common

vocabulary defined for maintenance applications in

hydraulic installations for EDF’s CIH group.

The EDF (Electricité de France) Group is a

leading player in the European energy industry. It is

present in all areas of the electricity value chain,

from generation to trading. Leader on the French

electricity market, EDF is also solidly implanted in

the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy.

The CIH (Centre d’Ingénierie Hydraulique)

group is in charge of hydraulic installations.

Hydraulic installations are complex structures where

many different technical domains have to be taken

into account: hydraulic turbines, alternators,

transformers, gates, regulation, etc.

One of the first tasks to perform was to define a

common dictionary. Each community of practice

speaks its own language but has to communicate and

exchange information with other communities

sharing the same environment and the same domain

conceptualisation. Ontoterminology enabled linking

the different vocabularies to the same

conceptualisation. It then became possible to

associate different terms belonging to different

communities to the same concept and vice versa, so

that the different ways of referring to a given

concept were known for each of them. It was also

possible to attach information to concepts, such as

reference documents (e.g. standards, schemas),

returns of experience, expert lists, etc. The result is a

software environment which is also used for learning

and knowledge capitalisation. Access information

relies on the domain ontology and provides new

ways of interactive navigation like hyper schemas.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Experts require terminology which clearly defines

terms in relation to the domain conceptualisation.

Even if term definitions written in natural language

are useful, they are not always consensual unlike

domain conceptualisation. Experts also require a

terminology which is able to manage and preserve

the diversity of language, for instance the capability

to use different words to denote the same concept.

We have introduced the paradigm of

ontoterminology, a terminology whose conceptual

model is a formal ontology, in order to separate the

definition of term (viewed as a linguistic

explanation) from the definition of concept

(considered as a logical specification). This implies

that a concept is neither a term nor a definition of a

term. The structure of ontology-oriented

terminology relies on the conceptual relationships

from which linguistic relationships can be built.

Furthermore, with such an approach new navigation

methods for browsing the knowledge base attached

to the terminology become possible. Ontology can in

fact be viewed as a conceptual map in which experts

navigate along the “is-a” and “part-of” relationships

in order to access to information attached to

concepts.

REFERENCES

Alexeeva, L.M. 2006. Interaction between Terminology

and Philosophy. Theoretical Foundations of

ONTOTERMINOLOGY - A New Paradigm for Terminology

325

Terminology Comparison between Eastern Europe and

WesternCountries. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag

Budin, G. 2001. “A critical evaluation of the state-of-the-

art of Terminology Theory”. ITTF Journal,12. Vienna:

TermNet

Buitelaar, P., Cimiano P., Magnini B. (2005), Ontology

Learning from Text: Methods, Evaluation and

Applications (Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and

Applications, Vol. 123). P. Buitelaar (Editor) Ios Press

Publication (July 1, 2005)

Cabré T. Theories in terminology. In Terminology 9:2

(2003), pp 163-199.

Daille B., Kageura K., Nakagawa H. and Chien

L.F. (2004), Recent Trends in Computational

Terminology, Special issue of Terminology 10:1

(Benjamins publishing company).

Gomez-Perez, A., Corcho. O., Fernandez-Lopez, M.

(2004), Ontological Engineering : with examples from

the areas of Knowledge Management, e-Commerce

and the Semantic Web. Asuncion Gomez-Perez, Oscar

Corcho, Mariano Fernandez-Lopez, Springer 2004

Gruber, T. (1993), A Translation Approach to Portable

Ontology Specifications. Knowledge Systems

Laboratory September 1992 - Technical Report KSL

92-71 Revised April 1993. Appeared in Knowledge

Acquisition, 5(2):199-220, 199

ISO 1087-1:2000. Terminology work-Vocabulary-Part1:

Theory and application. International Organization for

Standardization.

ISO 704:2000. Terminology work - Principles and

methods. International Organization for

Standardization.

Madsen, Bodil Nistrup & Hanne Erdman Thomsen. 2008.

“Terminological Principles Used for Ontologies.”

Managing ontologies and lexical resources. TKE 2008.

Copenhagen:ISV

Roche C. (2001). The “specific-difference” principle: a

methodology for building consensual and coherent

ontologies. IC-AI 2001, Las Vegas USA, June 25-28

2001

Roche, C. (2003), Ontology: a Survey. 8th Symposium on

Automated Systems Based on Human Skill and

Knowledge IFAC, September 22-24 2003, Göteborg,

Sweden

Roche, C. (2007), “Saying is not modelling”, NLPCS

2007 (Natural Language Processing and Cognitive

Science); pp 47 – 56. ICEIS 2007, Funchal, Portugal,

June 2007.

Sager, J. (1990), “A Practical Course in Terminology

Processing”, John Benjamins Publishing Company

Staab, S., Studer, R.: Handbook on Ontologies. Steffen

Staab (Editor), Rudi Studer (Editor), Springer 2004

Temmerman R. (2000), Towards New Ways of

Terminological Description. The Sociocognitive

approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Tricot C., Roche C. (2005), "Visual Information

Exploration: A Return on Experience in Knowledge

Base Management," in ICAI'05 - The 2005

International Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Las

Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2005.

Ushold, M., Gruninger, M. (1996), Ontologies: Principles,

Methods and Applications. Knowledge Engineering

Review, Vol. 11, n° 2, June 1996. Also available from

AIAI as AIAI-TR-191

Wright, S.E., Budin, G. (1997), “Handbook of

Terminology Management”, volume 1 and 2, John

Benjamins Publishing Company

KEOD 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

326