MODELLING COGNITIVE TRANSACTIONS FOR ECONOMIC

AND ACCOUNTING ANALYSIS

Ettore Bolisani

DTG, University of Padua, Stradella San Nicola 3, Vicenza, Italy

Keywords: Knowledge exchange, Economic transactions, Cognitive transactions, Abstract modelling.

Abstract: When knowledge is treated as a fundamental factor of economic activity, the development of methods

for assessing its economic value becomes essential. This issue has often been discussed both in the

scientific literature and for the managerial practice, but with controversial results. This position paper

argues that there is need to reflect on the foundational aspects of the problem, and suggests looking at

the way the exchange of knowledge between traders underpins economic transactions and enables the

production of economic value. A model of cognitive transaction, representing the way knowledge

exchanges have an economic significance per se, is proposed as a starting point of future research on

this issue. The critical and open questions of the application of this model, as well as the points of a

research agenda, are illustrated.

1 INTRODUCTION

A puzzling problem brought about by the so-called

knowledge economy is the need to assess the

economic value of knowledge. When knowledge is

considered a key resource of people, companies and

nations, it becomes essential to evaluate its

contribution to the production and accumulation of

value. This issue has been the subject of intense

research, but with controversial results. At a macro

level, international institutions have analysed the

possibility to measure the contribution of

knowledge and knowledge workers to the wealth of

nations (WBI, 2008). At a company’s level, there

have been efforts to value the intellectual capital

embedded in staff, organisational routines, or

artefacts (Hand and Lev, 2003). More recently, the

Knowledge Management (KM) field has given

birth to approaches to assessing knowledge in KM

practices (Kankahalli & Tan, 2004). However, a

clear consensus on a specific method or conceptual

approach has not been reached (Grossman, 2006).

In this position paper it is argued that there is the

need to go back to the roots of the problem, with an

in-depth reflection on the mechanisms by which

knowledge generates economic value for companies,

and on the possible ways of modelling these

mechanisms.

2 FOUNDATIONS

Here, it is proposed to consider the issue from a

micro perspective. As is assumed by the traditional

accounting approaches, an economic player (i.e. a

company) can be seen as a system of stocks and

flows. Stocks refer to wealth (cash, real estate,

accounts receivable, etc.) and flows refer to

expenditures or receipts between two specific

points in time. These two elements are observed

and recorded into the accounting charts, i.e. stocks

are shown on a balance sheet, and flows on an

income statement. The creation of economic value

– and its measurement – is therefore connected to

two main activities: a) the production of value by

means of operative activities over time (producing

goods, selling, delivering, etc.); and b) the

accumulation of value in appropriate repositories

(e.g.: goods bought; financial assets, etc.).

In addition, from an accounting perspective a

firm is not considered per se, for two main reasons:

first, it produces value by interacting with other

economic players (e.g. by trading with others);

second, the value of assets has a meaning that

depends on the external conditions, namely markets,

trading rules, etc. (Bolisani & Oltramari, 2009). In

practice, the economic value can be associated to the

economic transactions occurring between traders.

242

Bolisani E. (2009).

MODELLING COGNITIVE TRANSACTIONS FOR ECONOMIC AND ACCOUNTING ANALYSIS.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, pages 242-247

DOI: 10.5220/0002332502420247

Copyright

c

SciTePress

The notion of economic transaction is the

elementary element of many theories explaining the

functioning of markets, the inter-firm co-ordination

mechanisms, etc. An economic transaction is

defined as the activity of exchange between a seller

and a buyer: the seller transfers the property or

control of a physical object to the buyer, and obtains

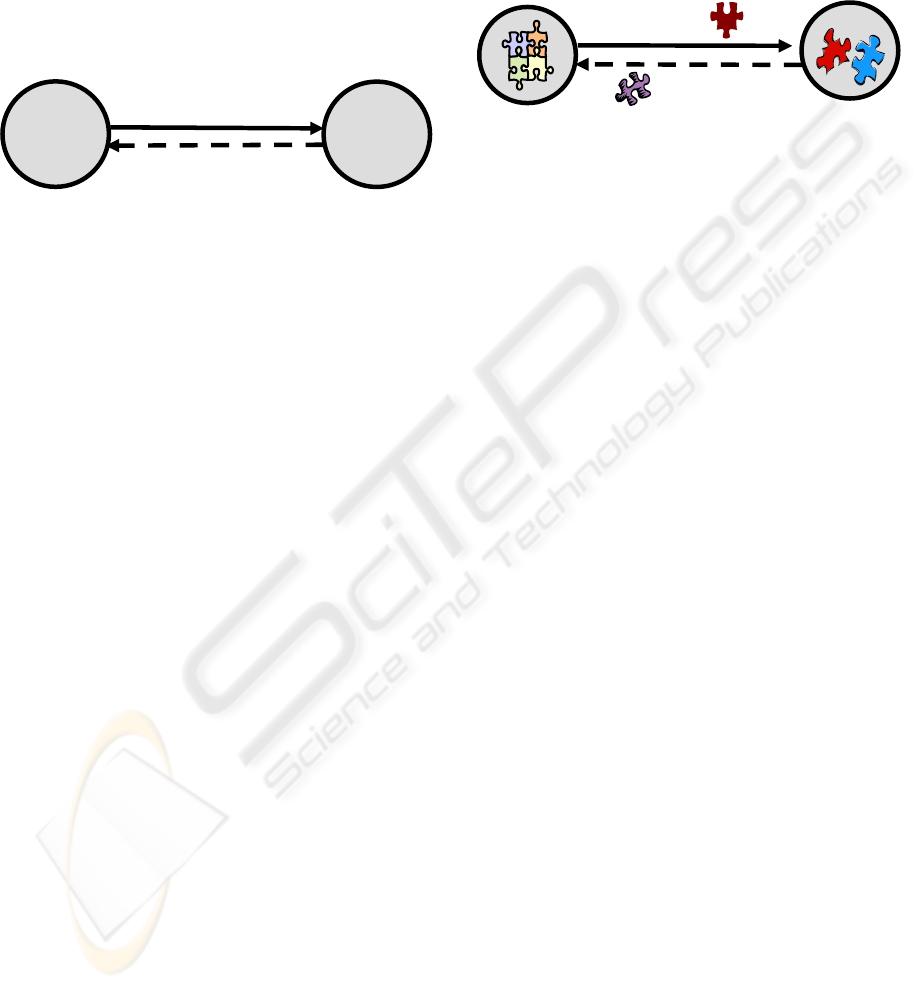

a payment (fig. 1). A transaction involving the

supply of services can be defined in a similar way.

Figure 1: Economic transaction.

Although the act of exchange can be sometimes

treated as an indivisible activity, there are several

situations in which a transaction needs analysing in

terms of its elementary parts, for practical or

analytical purposes (Gebauer & Scharl, 1999; Sarkar

et al., 1995). There are two crucial aspects here:

a) trading is not only a flow of goods/services

and a flow of payments: there is a third important

flow, a flow of communications: To define the

trading conditions and execute the material transfers,

the parties need to exchange several messages;

b) a transaction can be split into subsequent steps

(for instance: initial contact, negotiation, contract,

and material execution of exchanges). Each step

involves different actions and decisions, and requires

the exchange of various messages.

Here, it is argued that these messages carry

valuable knowledge, which is transferred between

seller and buyer. Modelling these exchanges and

assessing their value can shed some light into the

meaning of knowledge as an economic resource.

3 COGNITIVE TRANSACTIONS

A cognitive transaction is here intended as an

exchange of valuable knowledge between two

traders: these exchanges occur several times during

an economic transaction, and they are an essential

ingredient of it. As is well known, economic

transactions occur in an economy where each

player specialises in a particular activity. In a barter

market, the payment is another piece of goods or

service: the buyer needs a particular item or service

that she/he can not make on her/his own and vice

versa. When the payment is in the form of money

(which is, of course, the general situation), the

seller can use the received money to buy other

items or services from other sellers. The transaction

has an economic significance when the parties are

willing to accept the exchange because they expect

to gain an economic value or a personal utility.

Figure 2: Cognitive transaction.

By exploiting an analogy with this concept, a

cognitive transaction is defined as the act of

exchanging valuable pieces of knowledge (fig. 2): a

player “A”, that possesses some kind of knowledge,

transfers a piece of this knowledge to a player “B”,

and, as a payback, obtains another piece of

knowledge from B. Assuming that a player gives out

a piece of knowledge in the hope of receiving back

another one that she/he needs but does not possess

(for instance: something that completes the

understanding of a phenomenon, of the functioning

of a device, etc.), the situation becomes similar to

the classic notion of economic transaction

mentioned above, and especially a sort of barter

exchange of knowledge.

A cognitive transaction can be seen as kind of

communication, but with special characteristics

compared to other models proposed in the literature.

On the one hand, although the importance of

communication processes between traders has

already been highlighted by some economic theories

(just to recall some authoritative references, see e.g.

the theory of lemon markets Akerlof, 1970, or the

agency theory – Spence, 1973, and others), their

cognitive implications have often been neglected.

On the other hand, the notion of cognitive

transaction differs from that of “message

communication” or “information transfer” often

used in the Information Systems literature, or from

that of knowledge transfer usually defined in KM

(Boyd et al., 2007): in the model of cognitive

transaction there is an emphasis on the economic

value associated to the knowledge exchanged.

This also recalls a traditional distinction made in

the KM literature (Boisot, 1998): while data just

refer to measures of “facts” and phenomena, and

information is the meaning ascribed to those data,

we can talk of knowledge as data and information

Seller

Goods or services

Pa

y

ment

Buyer

knowled

g

e

knowled

g

e

A

A

B

MODELLING COGNITIVE TRANSACTIONS FOR ECONOMIC AND ACCOUNTING ANALYSIS

243

which have value for taking decisions or performing

actions. Therefore, the exchange of knowledge is

linked to the purposes and intentions that the players

have. When it comes to trading, since this activity

requires the willing to exchange something with the

purpose to achieve some goal, the economic

evaluation of this goal implies a cognitive process

and not simply an exchange of “pure” information or

“simple” data. In other words, although the

communication process between traders is still based

on some form of messages that contain data and

information, the act of trading is not just the

automatic consequence of these messages, but is

mediated by a cognitive process that enables the

traders to evaluate the economic significance of

those messages. This is what a cognitive transaction

is intended to model.

4 ILLUSTRATORY EXAMPLES

To summarise, any economic transaction is not an

atomic and indivisible activity, but also implies a

number of communication processes before,

during, and after the material exchange. These

communications involve processes of knowledge

exchange that, in turn, imply economic evaluations.

It is easy to recognise that a number of cognitive

transactions occur even in the simplest economic

transaction. To explain the concept, we can apply it

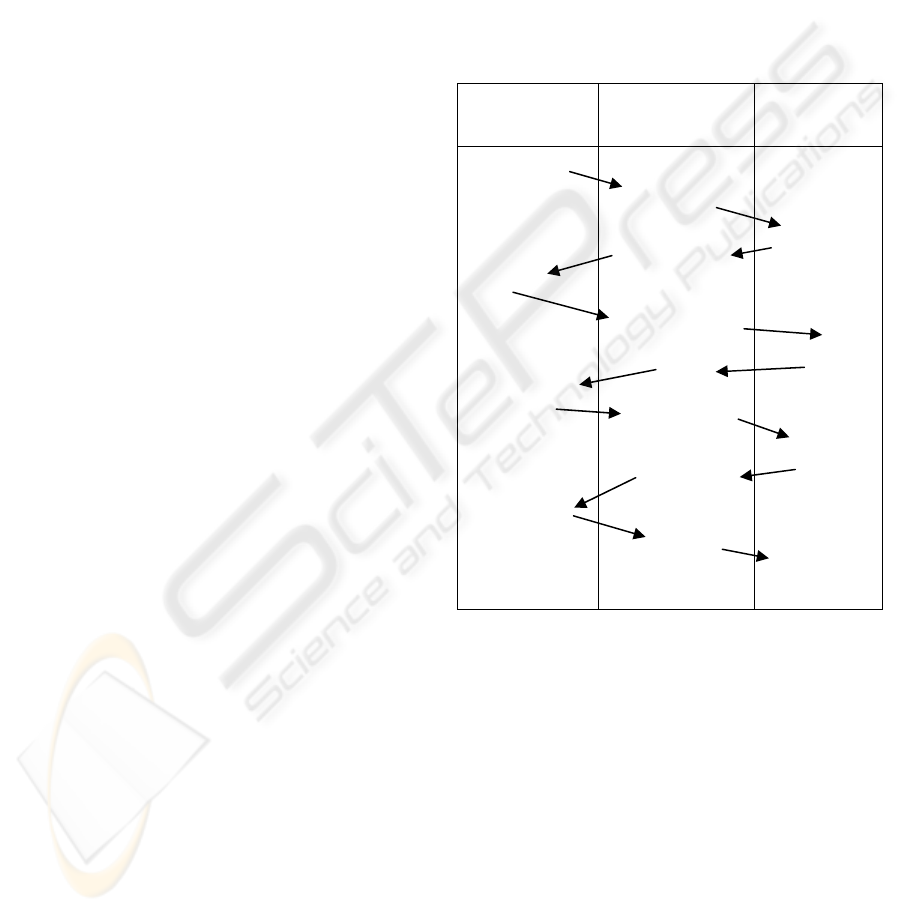

to an exemplary situation (fig 3).

Let A be a potential seller of some kind of goods

(for instance, bread), and B a possible buyer (willing

to buy some bread). In traditional terms (fig. 1) the

interaction would be modelled just as a material

exchange of a quantity of bread from A to B, and a

sum of money from B to A. When we analyse the

interactions between the two traders, we can identify

the occurrence of a number of cognitive

transactions, as described below.

1 - Before B passes by the shop, the baker has

already hung a “bakery” sign out of the door, which

is indeed the first part of a cognitive transaction: B

passing by the shop can read the sign and de-code

the message, learning that there is a shop selling

bread. Supposing that B is looking for some bread,

this piece of knowledge has a value for B.

2 - Entering the shop, B asks for some kind of

bread. This is a piece of valuable knowledge flowing

from B to A, who can now learn that a) there is a

potential customer in the shop, and b) that customer

likes some kind of bread. In turn, A re-pays B by

picking an item from her/his knowledge (i.e. the

knowledge of the available bread and its price) and

gives it to B, who now learns that there is something

that may be worth buying; B can use this fresh

knowledge to decide whether or not to carry on the

transaction; again, the piece of knowledge

exchanged has a value for B;

3 - B informs A about the intention to buy the

bread, and communicates the quantity; this message

is useful knowledge for A, who can start the

practical actions to carry out the material transaction

(i.e. taking the bread, wrapping it, etc.); A then

calculates the total price and communicates it to the

buyer; this piece of knowledge is necessary to carry

out the payment, etc.

SELLER’S

ACTIONS

(A)

Piece of knowledge

exchanged

BUYER’S

ACTIONS

(B)

Makes and hangs

up a sign

Checks available

bread and

price

Picks up and

wraps bread;

calculates price

Checks payment;

hands over

bread

A seller

is available

A potential

customer is looking

for a product

Kinds of product

and prices

Order

Price to be paid

Quantity of

money paid

product

Reads sign;

decides to get

into shop; asks

for bread

Decides

to buy

some bread

Collects and

hands over

money

Checks product;

Gets out from

shop

Figure 3: Example of cognitive transactions.

The representation of this process can continue,

but what described is enough to make some

important points. First, every communication in this

process has a cognitive implication, which requires

reflecting on the way each message is produced,

received, and used: The delivery of any message

implies a selection and codification of knowledge,

and its reception involves a learning activity.

Secondly, each transfer of knowledge involves an

economic value. As the example illustrates, A and B

carefully select the knowledge that they want to give

or take, based on personal value judgements.

Thirdly, to serve its purpose, the exchange is bi-

directional: to complete the trading activity, A needs

to give some valuable piece of knowledge (e.g. who

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

244

A is, what bread sells, at what price, etc.) and B

repays this knowledge with other valuable contents

(i.e.: what B likes, what price B can afford, etc.).

Finally, we can say that the exchanges of knowledge

have a value before and even regardless that the

material transaction is finally carried out.

This last point is of special importance, because

we can consequently argue that a cognitive

transaction has an economic value itself: indeed, the

knowledge received by one of the players can be

used in other circumstances. It is therefore important

to represent and study the cognitive transactions as a

separate process from the material exchanges.

This can be clearer if we mention other

situations, beside the hypothetical and simple

example described before. Let us consider a firm

whose job consists of carrying out projects for other

companies (for instance: the implementation of a

new plant). This activity implies a complex

economic transaction, whose significance can’t be

restricted to the activity of delivering a product and

getting a payment. The seller and the buyer need to

exchange several valuable pieces of knowledge well

before the material exchange is performed:

customer’s requirements, technical specifications,

design proposals, bids, etc. These pieces of

knowledge have great value for the two companies.

For the seller, the experience made with a customer

can be of use for future projects or to design new

products, and this can happen even regardless that

this specific transaction will be completed.

Similarly, the buyer may use the knowledge

acquired in the initial stages of the interaction to

compare the offers of other suppliers. Again, we can

claim that knowledge exchanges have themselves a

value.

5 ANALYSING COGNITIVE

TRANSACTIONS: CRITICAL

ISSUES

A cognitive transaction can become the foundation

of a method for assessing the economic value of the

knowledge exchanged by traders. However, to

achieve this goal, there is the need to clarify some

open questions that derive from the recent

literature.

5.1 Accounting Knowledge Flows and

Stocks

A possible reference for evaluating knowledge can

be the traditional accounting methods. As

mentioned before, accounting assumes a view of

the firm as a system of stocks and flows, that are

observed and recorded into the main accounting

charts. When a company trades with another one,

the accounting charts of the two companies

represent the effects of trade in terms of ongoing an

incoming flows of value, and of changes in the

companies’ stocks of value due to those flows. This

sufficiently well founded in the case of

manufacturing activities and trade of physical

goods.

Based on these assumptions, a first important

point in the development of the model of cognitive

transaction can be the exploration of the conditions

under which it this stock-and-flow model can be

transferred to the case of knowledge exchanged. To

do that, we need: a) to define the notions of

knowledge stock and knowledge flow; b) to clarify

their mutual relationship, and their link with the

notion of cognitive transaction, and c) to explore the

application of an accounting method similar to that

applied in traditional charts.

5.2 Economic Nature of Knowledge

Exchanged

A second important point is that, when we treat

knowledge as the matter of an economic exchange,

this requires new concepts and analytical tools, and

fresh managerial models as well. As mentioned,

although this issue is still puzzling, some recent

advancements in the studies of KM and knowledge

economy (KE) provide fresh perspectives that can be

of help for understanding how a cognitive

transaction works.

To evaluate the knowledge flowing from two

traders it is roughly possible to distinguish between

two kinds of situations: a) knowledge which is itself

the matter of an economic transaction (i.e.: a

company that provides training services or

consulting activities, a media company, etc.): in this

case, what is sold is directly knowledge; and b)

knowledge which is transferred before, during and

after the exchange of other goods, services, or

payments. A thorough analysis of this distinction is

important

Although it is the latter case that better

corresponds to the notion of cognitive transaction

previously illustrated, it is the former case which has

MODELLING COGNITIVE TRANSACTIONS FOR ECONOMIC AND ACCOUNTING ANALYSIS

245

been analysed more thoroughly in the KM and KE

literature. With regard to this, let’s briefly examine

some important findings of this research. In the

economic view, knowledge has often been

considered as a product of the R&D departments or

of other activities, products that can assume tangible

aspects (e.g. patents) or are incorporated into an

artefact which is then sold (e.g. a software code, a

research report, etc.). In such cases, some of the

economic characteristics that knowledge assumes

have been identified (cfr. Lev, 2001). For instance,

the notion of replicability and increasing returns:

when a company acquires a valuable “piece of

knowledge” from an external source (for instance, a

report from a consulting company), this knowledge

becomes part of the “buyer’s property”, but does not

necessarily mean that the source has a “lower

quantity” of that particular knowledge. In these

specific cases, knowledge is something that can be

replicated and then delivered at low or zero cost, and

is not simply something whose property passes from

a seller to a buyer, but it may be difficult to impede

the copy or imitation by others.

Related to these issues is the important

distinction between public and private knowledge.

Once knowledge is discovered, coded and published,

it becomes a piece of public goods, whose use does

not consume it (Foray, 2004): there is essentially

zero marginal cost to adding more users, which,

therefore, do not have to compete for the use of it.

The attempts to exchange this kind of knowledge in

a market are problematic because, in accordance to

the classic economic models, its price (i.e.: its

market value) should be equal to zero. On the

contrary, it is the private (i.e.: appropriable) use of

knowledge that has a value, because it allows its

owner to have a competitive use of it. In summary,

the more a piece of knowledge is private at

appropriable, the more has a value, but at the same

time it is difficult to trade it because in doing this

knowledge tends to become public and then loses its

value. This can have implications for the modelling

of a cognitive transaction.

The aforesaid findings have improved our

understanding of knowledge as a matter of economic

exchange, but as Foray (2004) argues, they also

represent an attempt of economists to remain in a

“comfortable world” for their analysis, while the

reality is much more complex. For instance, their

view requires that it is possible to identify single

knowledge objects passing from a player to another,

but as Iandoli & Zollo (2007) argue, knowledge can

be intended as an object but also as a process. In the

former case, we have pieces of knowledge that can

be detached from the people that process them. In

the latter case, knowledge has no meaning when

detached from the individuals that process it. In the

former case, the identification and valuation of

knowledge assumes an objective nature. But in the

latter case, knowledge has no meaning when

detached from the individuals that process it.

Therefore, the focus necessarily shifts: measuring

the value of knowledge can require to measure the

effects on the people that process them (for instance:

the results of learning), which gives a subjective

meaning to both the process of measurement and the

value measured. Consequently, knowledge has only

a partial and incomplete tradability and it would be

difficult to ascribe a value to it without considering

its effect on the experiences

of the individuals (see

e.g. the notion of experience goods - Nelson, 1970).

The reflection on the real nature of knowledge

recalls the well known classification of explicit vs.

tacit knowledge (Polanyi 1967): the former is the

component of knowledge that can be more easily

codified and detached from its creator, the latter is

the component which can not be coded, and is

mostly embedded in people. As the KM literature

clearly shows, this concept is associated with the

degree of difficulty of knowledge transfer and the

possible tools (and even technologies) that can be

used for this: tacit knowledge, being embedded in

the mind of people and therefore less easy to transfer

as an independent object. It also tends to be more

appropriable and, consequently, more valuable for

the owner. Conversely, explicit knowledge is more

easy to transfer but, for this reason, can more easily

become public and therefore less valuable (or, at

least, less valuable in competitive terms). The notion

of cognitive transaction should take into account

these points.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this position paper the notion of cognitive

transaction is proposed as a fundamental element of

economic transactions. According to this model, an

economic transaction is seen as (and requires) a

series of knowledge exchanges. Two traders need

to exchange pieces of knowledge, which implies an

exchange of economic value per se. Understanding

the value of the exchanged knowledge helps to see

the nature of economic transactions from a new

perspective, and can shed light on the cognitive

implications of economic activities.

The application of this concept needs a number

of advancements that, in turn, can represent the

KMIS 2009 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

246

points of a future research agenda. In particular, the

achievements of the studies of KM and KE about the

mechanisms of knowledge transfer and the nature of

knowledge as economic resource need to be

systematised to be fruitfully applied to this notion.

Here, some important issues have been

pinpointed. First, the nature of knowledge as the

matter of an exchange, which implies a reflection on

the ways the value of knowledge can be intended

and measured. This is also associated with the

identification of the different manifestations of

knowledge (for instance: knowledge as object or

process, tacit vs. explicit components, public or

private nature, etc.), the practical tools that can be

used to perform its transfer, and the way all these

influence the mechanism of a cognitive transaction.

Secondly, since the notion of cognitive transaction is

applied to the economic exchanges between firms

and, more generally, economic players, a more

direct connection with the functioning of markets

and with the nature of economic exchanges as they

are studied in the economic literature or considered

in the accounting practices is essential.

Another important point is directly associated

with the way the notion of cognitive transaction has

been explained here. In the example illustrated in

section 4, this notion was applied to individuals. In

that case, there is a perfect overlapping between

those who exchange knowledge and those who

trade. In practical situation, this may or may not

happen. For instance, in the economic models the

majority of business transactions are intended (and

modelled) as being performed between entire firms,

or at least parts of a company (for instance, the Sales

department, the procurement office, etc.). This

requires a reflection about the different subjects (or

levels) to which the notion of cognitive transaction

should be applied. Also, an identification of the

various cases of cognitive transactions that may

occur in the distinct cases is necessary.

All this gives the opportunity to draw an agenda

for future studies, which may include:

- the application of the notion of cognitive

transactions in distinct theoretical cases, to test its

validity and utility;

- the validation of the notion with specific empirical

situations, to test its plausibility as a model of

reality;

- a more thorough analysis of the utility of the notion

as a descriptive or prescriptive tool for the economic

or managerial studies. It should be therefore

explored what the understanding of the functioning

of cognitive transactions can really add to our

representations of economic activities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper contributes to a FIRB 2003 project

funded by the Italian Ministry of University and

Research.

REFERENCES

Akerlof, G.A., 1970. The Markets for “Lemons”: Quality

Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism, Quarterly

Journal of Economics, August, pp. 488-500

Boisot M., 1998, Knowledge Assets: Securing Competitive

Advantage in the Information Economy. Oxford:

Oxford University Press

Bolisani E., & Oltramari A., 2009, Capitalizing flows of

knowledge: models and accounting perspectives.

IFKAD Conference, University of Glasgow, 17-18

February

Boyd, J., Ragsdell, G., & Oppenheim, C. , 2007,

Knowledge Transfer Mechanisms: A Case Study from

Manufacturing. 8

th

European Coference on Knowledge

Management, Barcelona, 6-7 September

Foray D., 2004, The Economics of Knowledge. Boston:

MIT Press.

Gebauer J., & Scharl A., 1999, Between Flexibility and

Automation: An Evaluation of Web Technology from

a Business Process Perspective, Journal of Computer

Mediated Communication, 5(2)

Grossman, M., 2006. An Overview of Knowledge

Management Assessment Approaches. The Journal of

American Academy of Business, 8(2), 242-247

Hand J. & Lev B. (eds), 2003. Intangible Assets. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Iandoli L., & Zollo G., 2007. Organizational Cognition

and Learning. Hershey PA: IGI Publishing

Kankanhalli, A., & Tan, B.C.Y., 2004. A Review of

Metrics for Knowledge Management Systems and

Knowledge Management Initiatives. 37

th

Hawaii

International Conference on Systems Sciences

(HICSS) (pp.238-245). Computer Society Press

Lev B., 2001. Intangibles. Management, Measurement,

and Reporting. Washington: Brookings Institution

Press

Nelson P., 1970. Information and Consumer Behavior.

Journal of Political Economy, 78(2)

Polanyi, M. 1967. The Tacit Dimension. Garden City

(NY): Doubleday Anchor,

Sarkar, M.B., Butler, B., & Steinfield, C., 1995.

“Intermediaries and Cybermediaries: A Continuing

Role for Mediating Players in the Electronic

Marketplace. Journal of Computer Mediated

Communication, 1(3)

Spence M., 1973. Job Marketing Signals. The Quarterly

Journal of Economics, 87.

WBI, 2008, Measuring Knowledge in the World’s

Economies. [Online] World Bank. Available at

siteresources.worldbank.org/INTUNIKAM/Resources/

KAM_v4.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2009]

MODELLING COGNITIVE TRANSACTIONS FOR ECONOMIC AND ACCOUNTING ANALYSIS

247