TOWARDS FULLY AUTOMATED PSYCHOTHERAPY

FOR ADULTS

BAS - Behavioral Activation Scheduling Via Web and Mobile Phone

Fiemke Both

1

, Pim Cuijpers

2

, Mark Hoogendoorn

1

and Michel Klein

1

1

Dept. of Artificial Intelligence, VU University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1081a, 1081HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2

Dept. of Clinical Psychology, VU University Amsterdam, van Boechorststraat 1, 1081 BT Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Keywords: Automated psychotherapy, Agent model.

Abstract: Behavioural activation treatment has been found to be an effective psychological treatment for depression,

also if delivered as self-administered psychotherapy via the internet. However, the role of supporting

professionals remains important for successful application of the therapy. In this paper a system is presented

that delivers automated behavioural activation therapy via both a mobile phone and a personal website. The

system motivates the client to continue with the treatment and helps him/her through the different

procedures of the treatment. The architecture of the system follows a generic ambient agent architecture. A

first pilot study of the system indicates that it is technically feasible and perceived as useful.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dozens of well-designed studies and meta-analyses

have shown that psychological interventions are

effective in the treatment of depressive disorders in

adults (Cuijpers et al., 2007; Churchill et al., 2001;

Leichsenring, 2001; Gloaguen et al., 1998). There is

also a growing number of studies showing that self-

administered psychotherapies are effective in the

treatment of depression. In such a therapy, a patient

can read in a book or on a website step-by-step what

he can do to apply a generally accepted

psychological treatment to himself.

Although self-administered treatments are

mainly conducted by clients themselves, the role of

supporting professionals remains important for

successful application of the therapy (Spek et al.,

2007a). In general it is assumed, that professional

support is needed to motivate the client to continue

with the treatment and to help him/her through the

different procedures of the treatment.

It would be attractive to develop a psychological

treatment that does not need a professional therapist,

but still has some automated actor involved to

interact frequently with the client. The current

project addresses the development of an automated

interactive psychotherapy for depression: BAS

(behavioural activation scheduling). The core is a

systematic internet intervention in which the patient

plans her daily activity (based on the principles of

behavioural activation therapy, see below). The

patients use a mobile phone which will help them

during the day to work through the behavioural

activation treatment. This daily support (through the

mobile phone) is fully automated.

In this paper, the design of the BAS automated

psychotherapeutic system as instantiation of

intelligent ambient agent system is presented

(Section 3) and first experiences within a pilot study

are reported (Section 4). First the psychological

intervention activity scheduling that is the basis of

the current project is described in Section 2. Finally,

the paper is concluded with a discussion.

2 ACTIVITY SCHEDULING

Activity scheduling (AS, also called behavioural

activation) is an intervention for clinical depression

based on a theory by Lewinsohn, Youngren &

Grosscop (1979) who say that a low rate of

behaviour (often caused by inadequate social skills)

is the essence of a depression and the cause of all

other symptoms. Part of his theory is the hypothesis

that there is a causal relationship between lack of

positive reinforcement from the environment and the

depression. A depression can be treated by

increasing the positive reinforcement through

375

Both F., Cuijpers P., Hoogendoorn M. and Klein M. (2010).

TOWARDS FULLY AUTOMATED PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR ADULTS - BAS - Behavioral Activation Scheduling Via Web and Mobile Phone.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 375-380

DOI: 10.5220/0002688503750380

Copyright

c

SciTePress

increasing the quantity and quality of (social)

activities. Many studies have shown that this type of

intervention works just as well as or even better than

other popular treatments (Dimidjian et al, 2006;

Jacobson et al, 1996). Recently, it is shown that

interventions of this type offered via the internet are

very effective (Christensen et al, 2004; Andersson et

al, 2005, Spek et al, 2007b).

There are two stages in AS treatment: the first

stage is observing that pleasant activities and a good

mood come together by writing down all pleasant

activities and mood level. The second stage is

changing the activity schedule so that the patient

participates in more pleasant activities with the goal

of increasing the mood level. The mood increases on

a short term, and by learning that pleasant activities

influence mood level positively, patients are more

capable of dealing with future situations.

For the BAS intervention, this intervention as

been implemented in a five-step plan: 1) rating the

mood via a mobile phone or via a website; 2)

registering their current pleasant activities and rate

them; 3) actively planning more pleasant activities

and setting a goal for the desired mood level at the

end of the intervention; 4) encouraging to keep

doing more pleasant by giving automated weekly

feedback; 5) continue scheduling pleasant activities.

In addition, a plan for the future can be made to help

prevent relapse and reoccurrence of depression.

3 AGENT MODEL

Automated psychotherapy via website and mobile

phone can be seen as an instance of Ambient

Intelligence applications, where software has

knowledge about human behaviours and states, and

(re)acts on these accordingly (

Aarts et. al., 2003). For

this class of applications an agent-based generic

model has been developed (Bosse et. al., 2009). This

model can be instantiated by case-specific

knowledge to obtain a specific model in the form of

executable specifications that can be used for

simulation and analysis. In this section, the

automated psychotherapeutic intervention will be

described using this generic framework.

3.1 Generic Framework for Human

Ambience applications

For the global structure of the generic model for

human ambient applications, first a distinction is

made between those components that are the subject

of the system (e.g., a patient to be taken care of), and

those that are ambient, supporting components.

Moreover, from an agent-based perspective, a

distinction is made between active, agent

components (human or artificial), and passive, world

components (e.g., part of the physical world or a

database).

Second, interactions between model elements are

defined. An interaction between two agents may be

communication or bodily interaction, for example,

fighting. An interaction between an agent and a

world component can be either observation or action

performance. An action is generated by an agent,

and transfers to a world component to have its effect

there. An observation results in transfer of

knowledge from the world component to the agent.

Combinations of interactions are possible, such as

performing an action and observing the effect of the

action afterwards.

Finally, ambient agents are assumed to maintain

knowledge about certain aspects of human

functioning in the form of internally represented

dynamic models, and information about the current

state and history of the world and other agents.

Based on this knowledge they are able to have a

more in-depth understanding of the human

processes, and can behave accordingly.

3.2 Agent System Overview

Figure 1 gives an overview of the different

components in the ambient agent model. In the

remainder of this section, the components and their

specific interactions are described. In Section 3.3,

the internal knowledge of the specific agents is

given.

Figure 1: Components in the ambient agent model.

The subject components are the following:

Subject agents: participant suffering from a

depression.

Subject world components: mobile phone of the

participant, computer of the participant with a

dedicated website.

The subject interactions:

AMA

mobile phone website

PA FBA

PAA

subject agent (patient)

subject

world components

ambient agents

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

376

Observations and actions by subject agents:

Participant inputs information requested for therapy

into either the mobile phone or the website via a

computer. This includes:

Mobile phone actions by participant:

• Mood rating (number between 1 and 10)

• Activity rating (number between 1 and 10)

• Request advice

Mobile phone observations by participant:

• Activity schedule

• Tips

Web site actions:

• Planning activities

• Planning rewards

• Adding possible activities to a list

• Setting goals for the week

Web site observations

• Information about therapy, explanation

• Outcome of all actions performed (see above)

The ambient components are the following:

Ambient agents: activity monitoring agent (AMA),

patient assessment agent (PAA), feedback agent

(FBA), activity planning agent (APA)

The following ambient interactions are

distinguished:

Communication between ambient agents: the

AMA sends the information about the monitoring

and rating of activities to the PAA, APA sends

schedule and information to the PAA, PAA sends

feedback to the FBA.

And finally, the following interactions between

subjects and the ambient components:

Reminders

• Planned activities (AMA – mobile phone)

• Rating of mood (AMA – mobile phone)

• Rating of performed activities (AMA – mobile phone)

Reporting about ratings and activities

• Rating of mood (website / mobile phone – AMA)

• Rating of performed activities (website / mobile phone

– AMA)

• Planned activities (website – APA)

Feedback

• Motivational remarks (FBA – website / mobile

phone)

• Weekly feedback (FBA – website / mobile phone)

o Plots of mood versus number of activities

and rating of activities

o Remarks about mood during week

o Remarks about activities during week

o Remarks about combination of mood and

activities

o Feedback on targets set for week

3.3 Individual Agents

AMA: Activity Monitoring Agent

This agent is responsible for monitoring which

activities have been performed by the patient and

what the mood of the patient was at different

moments (specifically after doing activities).

Maintenance of Agent Information. Maintain the

ratings of the mood and the list of performed

activities. Maintain preferences concerning how

frequent reminders should be sent and the reminders

that have already been sent.

Agent Specific Task. Based upon the information

present: derive reminders. There are two types of

reminders, namely (1) reminding the participant of

the planned activities, and (2) reminding the

participant to rate the activity and the mood.

Reminders for planned activities

The agent sends out such a reminder in case:

1. The participant requested a reminder (by indicated it

in the activity schedule).

2. In case of a pattern of missed activities:

a. If the participant has missed a specific activity 2

times in a row, or 2 out of 3 times. The reminder

is then sent half an hour before the activity is

planned.

b. If the participant has missed two activities in

general on a particular part of the day (e.g. never

performs activities in the morning). Again the

reminder is sent half an hour before the activity

has been planned.

Reminders for mood and activity rating

Next to the monitoring of activities being followed,

reminders of the rating of these activities are also

sent. This is done when during the past three days

less than 50% of the planned activities have been

rated. Reminders for mood rating are sent based on

the following mood rating frequency settings.

World Interaction Management. Process the

information about performed activities, ratings and

mood inserted into the mobile phone or via the

website. Send reminders to the mobile phone (i.e.

the patient).

Agent Interaction Management. Communicate the

fact that ratings have been given to the PAA.

APA: Activity Planning Agent

The APA keeps track of the planned activities and

reports this to the PAA.

Maintenance of Agent Information. Maintain

information about the activities that are planned by

the patient.

Agent Specific Task. Based upon the information

provided by the user and the options in the phase of

TOWARDS FULLY AUTOMATED PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR ADULTS - BAS - Behavioral Activation Scheduling Via

Web and Mobile Phone

377

Table 1: Reminder frequency for mood rating.

Mood rating

setting

First

reminder

Second reminder

(email)

Contact care

taker

3 times per day

After four

misses,

afternoon of

day 2

After a full day

without response

upon first reminder

After a full day

without

response on the

second

reminder

1 time per day

After one

miss, evening

of day 2

After a full day

without response

upon first reminder

After a full day

without

response on the

second

reminder

1 time per 2

days

After one

miss, end of

day 3

After a full day

without response

upon first reminder

After a full

day without

response on

the second

reminder

the therapy: maintain a schedule of activities.

World Interaction Management. Process the

information inserted into the website.

Agent Interaction Management. Communicate the

schedule on request to the PAA.

FBA: FeedBack Agent

The role of this agent is to communicate information

via either the mobile phone or the website based on

the analyses of the PAA. This can be weekly

feedback, daily motivational remarks or general

conclusions about the progress of the therapy

derived by the PAA.

Maintenance of Agent Information. Maintain

preferences with respect to the media that is

preferred (and suited) for specific type of feedback,

and keep track of the feedback that has been sent.

Agent Specific Task. Triggered by the PAA:

generate weekly feedback, select motivational

messages, or forward analysis from PAA to the

patient.

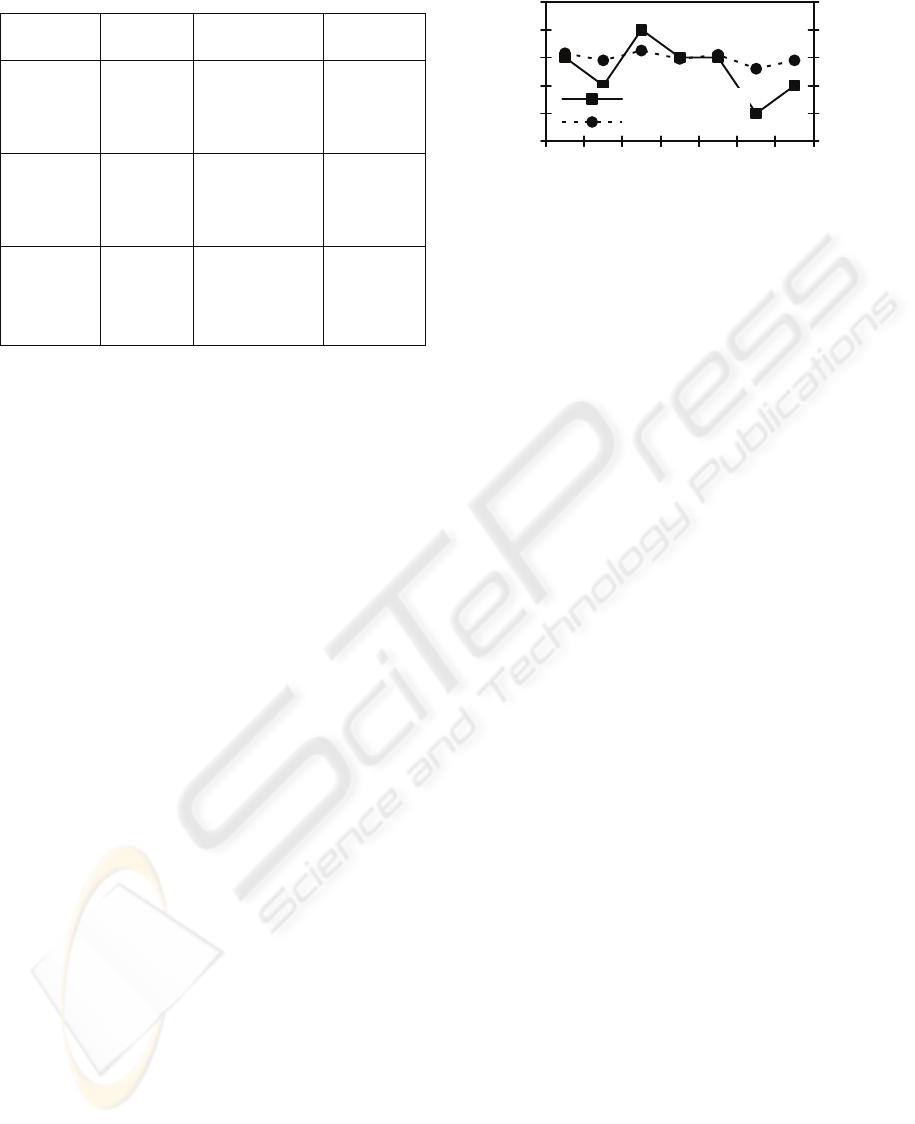

Weekly feedback

The weekly feedback is meant to create awareness

of the participant that there is a relationship between

mood and the activities being performed. First of all,

in week one and two of the therapy overviews are

given of the number of activities in relation with the

mood (see Figure 2) as well as a similar figure

showing the relation between the rating of the

activities and mood.

Motivational remarks

Furthermore, also motivational remarks are sent; this

is triggered by the PAA when it receives information

from the AMA that the patient has rated either

his/her mood or activities. Maximum of one

message per day:

0

1

2

3

4

5

mon tue wed thu fri sat sun

# activities

0

2

4

6

8

10

avg. mood rating

# activities

avg. mood rating

Figure 2: Number of activities and mood rating per day.

1. Communicate the highest mood of the past three days

if this is higher than ‘6’, also communicate the

activities during that particular day: “Your highest

mood during the last three days was on X: a Y! That

day you performed the following activities: [list of

activities and rating].

2. Communicate an encouraging message in case the

rating for mood just inputted was ‘6’: “You rated

your mood at X now, how nice!”. In case it was ‘7’:

“You rated your mood at X now, that’s really nice!”.

Or in case of an ‘8’ or higher: “You rated your mood

X, that’s excellent!”.

3. Communicate the percentage of tasks that have been

performed, given that during the last 3 days at least 2

activities have been performed. In case more that

70% of the activities have been performed: “The last

three days your adherence to the planning was very

good, you performed X activities, which is Y% of the

scheduled activities”. In case less than 50% has been

performed: “You did not adhere that well to the

planning during the last 3 days, you performed X% of

the activities, which totals to Y activities. Try to

adhere to your agenda somewhat better”. In all other

cases: “During the last 3 days you performed X% of

your planned activities”.

4. If the average mood of day 4 of the week is at most

0.5 of the goal mood (in case applicable in the stage

the participant is in): “Your average mood this week

is X, you’ve almost achieved your goal. Keep this up

till the end of the week! Thereafter you can reward

yourself with Y”. Note that the last part of the remark

is only communicated in case specific rewards have

been specified.

In case none of the above hold or are sent on the

current day a tip is sent (from a list of expert tips).

World Interaction Management. Sends messages

to the website or the mobile phone.

PAA: Patient Assessment Agent

The task of the PAA is to assess the status of the

patient and to guide which feedback is given at what

moment to the patient via the FBA.

Maintenance of Agent Information. Maintain

information about the history of the patient, in terms

of prior mood ratings, activities performed, and

ratings for the activities. Maintain information

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

378

about the phase of the therapy.

Maintenance of World Information. Keep track of

the time.

Agent Specific Task. Based upon the information

present: derive conclusions about the performed

activities and ratings in the past week. When

considering the reported mood of the patient and the

performed activities, the following abstracted

remarks can be generated and sent to the FBA:

• Mood: “Your average mood during this week was A,

on day C your mood was lowest, namely B”.

• Activities: “You performed E fun activities this week,

on average this is D fun activities per day”.

• Mood in combination with activities: “Your low

mood on day C corresponds with few pleasant

activities, namely F. This shows that doing less fun

activities can decrease your mood level”.

After the two week period more elaborate

conclusion are generated. For the sake of brevity,

these rules are not shown.

Agent Interaction Management. Send messages to

be communicated to the patient to the FBA.

4 PILOT STUDY

4.1 Participants and Method

A total of nine participants joined the pilot study for

the system, all students at the VU University

Amsterdam, age ranging between 18 and 24

(average 21.2). They followed the intervention

during three weeks after a start-up meeting. During

that meeting, they received a Sony Ericsson M600i

mobile phone, a link to the website and a brief

explanation of the intervention. All participants were

instructed to follow all assignments and to test the

system. In addition, they were asked to describe any

technical errors in detail. After every week the

participants provided feedback about the

intervention. These interviews were semi-structured,

The questions were structured in five groups: look

and feel, technical, textual, reminders and weekly

feedback. In the end, the participants handed over

their phones and received €100 participation fee and

an online questionnaire was filled in.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Weekly Feedback Sessions

Look and Feel. Most comments on the look and feel

of both the website and the application on the phone

were made after the first week. Negative comments

were about broken and illogically placed links, the

layout of the menu and the font size of some of the

forms. Four of the nine participants complained

about the simple agenda feature: they would have

liked to see more functionality such as a week

overview, setting an end time for activities and a

warning message when two activities are planned at

the same time. Remarks about the mobile phone

application were about functionalities people

missed, such as changing the comments about a

mood rating after saving the rating and adding or

changing agenda activities. Some participants had

difficulties interacting with the mobile phone itself.

Technical. The participants did not find many

technical problems with both applications. Some

complaints: the option ‘I did not do this activity’ was

missing, and it was possible to give a mood rating of

days in the future. Two participants received an error

message on their phone after saving a mood or

activity rating; this had to do with the motivational

remark that was shown afterwards.

Textual. Apart from some spelling and grammar

mistakes, the texts on the website were found very

clear. However, more explanation about the mobile

phone application and about when reminders could

be expected was required according to most

participants. In addition, no information about the

transition between steps was provided and some

participants were surprised when they automatically

started with the next step.

Reminders. The reminders for rating mood and

activities were judged as useful but the frequency

(see Table 1) could be improved. Some participants

found that the first reminder came too soon; others

found that it came not soon enough.

Reminders before a planned activity also showed

a pattern, although none of the participants noticed

it. They all said these reminders seemed random, but

were useful despite the randomness.

Weekly Feedback. Eight out of nine participants

said that they enjoyed reading the weekly feedback

and that the content matched their own experience

during that week. A few of the automatically

generated sentences needed more explanation, and

the percentages should be rounded.

4.2.2 Evaluation Questionnaire

The results of the final evaluation questionnaire

about how much the course was enjoyed are shown

in Table 2. To the question ‘how useful was the

course for you’ only one participant answered no,

six answered a little and two answered a lot. A

surprising result since none of the participants was

diagnosed with depression. Apart from the

TOWARDS FULLY AUTOMATED PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR ADULTS - BAS - Behavioral Activation Scheduling Via

Web and Mobile Phone

379

complaints about the frequency, the reminders that

the participants received on their phone were judged

as very useful. In general, the participants found

using the mobile phone for mood rating a nice

functionality, mostly because a mobile phone made

it easier to rate mood several times a day compared

with using a computer. The participants were also

asked to score the overall intervention on a scale of

1 to 10: the mean score was 7.1.

Table 2: Results of the evaluation, the scale is from 1

(totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Question Mean answer

the information was new 2.7

I enjoyed viewing the website 3.8

I enjoyed working with the phone 3.8

the course was interesting 4.3

5 DISCUSSION

Based on the results of the pilot study, some changes

have been made in a new version of the BAS

system. The few technical issues are solved and

some texts were revised. Based upon the critic of the

participants on the weekly feedback and the

unexpected evolving to the next step, three new

general messages have been added. Furthermore,

the agenda functionality on the website is extended.

The rating system on the mobile phone is changed

slightly, so that people can edit the comment field

after saving the rating. The final adjustment is made

in the reminder system: besides the mood rating

setting (see Table 1), there is also a reminder

frequency setting with the options low, medium and

high. A combination of the two settings determines

when a reminder is sent. When the reminder

frequency is set to high, the participant receives a

reminder after missing two rating moments, when

set to medium, a reminder is sent after three missed

rating moments and when set to low after four

missed rating moments.

The pilot study indicates that advanced support

via a website and mobile phone during activity

scheduling intervention is technically feasible and

perceived as useful. In the near future, a second pilot

study will be conducted with between five and ten

participants who suffer from a depression. The

participants will be questioned in the same manner

as described in this paper. After processing the

results, an efficacy study will be performed with

around 100 participants with a depression to

determine whether their depression is lessened by

the BAS intervention system.

REFERENCES

Aarts, E.; Collier, R.; van Loenen, E.; Ruyter, B. de (eds.)

(2003). Ambient Intelligence. Proc. of the First

European Symposium, EUSAI 2003. LNCS, vol. 2875.

Springer Verlag, 2003, pp. 432.

Andersson, G., J. Bergstrom, F. Hollandare, P. Carlbring,

V. Kaldo & L. Ekselius (2005). Internet-based self-

help for depression: randomised controlled trial.

British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 456-461.

Bosse, T., Hoogendoorn, M., Klein, M.C.A., and Treur, J.,

A Generic Architecture for Human-Aware Ambient

Computing. In: Mangina, E., Carbo, J., and Molina,

J.M. (eds.), Agent-Based Ubiquitous Comp. Amb. and

Perv. Int. book series., pp. 35-62, Atlantis Press, 2009.

Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R, Knapp M, McGuire H,

Tylee A, Wessely S. (2001) A systematic review of

controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-

effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for

depression. Health Technol Assess, 2001; 5: 35.

Cuijpers P, van Straten A & Warmerdam L. (2007)

Behavioral treatment of depression: A meta-analysis

of activity scheduling. Clin Psychol Rev; 27: 318-326.

Dimidjian, S. et al., Randomized trial of behavioral

activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant

medication in the acute treatment of adults with major

depression, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74 (2006), pp.

658–670.

Gloaguen V, Cottrauxa J, Cucherata M & Blackburn IM.

(1998) A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive

therapy in depressed patients. J Affect Dis; 49: 59-72.

Jacobson, N.S., Dobson, K.S., Truax, P.A., Addis, M.E.,

Koerner, K., Gollan, J.K., Gortner, E., & Prince, S.E.

(1996). A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral

treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 62, 295-304.

Lewinsohn, P.M., Youngren, M.A., & Grosscup, S.J.

(1979). Reinforcement and depression. In R. A. Dupue

(Ed.), The psychobiology of depressive disorders:

Implications for the effects of stress (pp. 291-316).

New York: Academic Press.

Leichsenring F. (2001) Comparative effects of short-term

psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-

behavioral therapy in depression: A meta-analytic

approach. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21: 401-419.

Spek, V.R.M., Nyklicek, I., Smits, N., Cuijpers, P., Riper,

H., Keyzer, J.J., & Pop, V.J.M. (2007a). Internet-based

cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold

depression in people over 50 years old: A randomized

controlled clinical trial. Psy. Med., 37(12), 1797-1806.

Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklíček I, Riper H, Keyzer J & Pop

V. (2007b) Internet-based cognitive Behavioral

Therapy for mood and anxiety disorders, a meta-

analysis. Psy. Med. 2007; 37: 319-328.

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

380