HUMAN STRESS ONTOLOGY

Multiple Applications and Implications of an Ontology Framework in the Mental

Health Domain

Ehsan Nasiri Khoozani and Maja Hadzic

Digital Ecosystems and Business Intelligence Institute (DEBII),Curtin University of Technology

De Laeter Way, Technology Park, Perth, Australia

Keywords: Human Stress, Ontology, Human Stress Ontology (HSO).

Abstract: A large number of articles exist that discuss and define various concepts, terms, and theories relating to

human stress. The heterogeneous and dynamic nature of this knowledge, and the growing research,

highlight the need and significance of designing a coherent and sharable ontology framework for human

stress domain. In response to this need, we design Human Stress Ontology (HSO) to capture stress-related

concepts and their relationships in an agreed and machine readable framework. This ontology is organized

according to the following five sub-ontologies: causes, mediators, effects, treatments and measurements.

Development of an ontology in this field will facilitate interoperability between different information

systems and enable the design of ontology-driven software programs tools and semantic web engines for

intelligent access, management, retrieval and analysis of stress-related information. The derived knowledge

will help identify important relationships between different concepts, and facilitate invention of more valid

and consensual psychological tests and development of effective prevention and treatment strategies.

1 INTRODUCTION AND

MOTIVATION

In a recent Newspoll Omnibus Survey, about 91% of

adult Australians reported feelings of stress in at

least one significant aspect of their lives. In this

study, worries about work, finances, future, health,

and personal relationships have been identified as

the main stressors (Lifeline Australia, 2008).

Stress can engage a wide range of psychological

and physiological mechanisms and have transient or

lasting effects on different cognitive, emotional or

physiological functions. The detrimental effects of

chronic and intense stress on physical and mental

health have been demonstrated in various studies

(Harris, 1991). For example, it can interfere with the

secretion of insulin resulting in susceptibility to

diabetes. Stress also underpins the hypersensitivity

of the limbic system resulting in subsequent arousal

disorders (Everly and Lating, 2002).

Various theories have been proposed and

experiments have been conducted in order to study

the effects of stress as a main or mediating factor in

different mental, neurophysiological, or

physiological conditions. A huge range of

information and data about such theories and their

relevant diverse studies are stored in various data

resources, yet there are ongoing controversies and

arguments over conceptualization, measurement

(Monroe, 2008), and classification of stress-related

phenomena.

An extended range of concepts, categories,

theories, and findings from stress-related studies can

be found in different texts and electronic journals

across various information resources. However,

there are a number of issues and problems regarding

effective analysis, integration, retrieval, and

application of these data.

Firstly, there is a lack of shared, consensual, and

precise definitions of stress-related terms and

concepts in some cases which have resulted in the

same concepts having different meanings in

different studies, or one concept being represented

by different terms across various research works.

For instance, the lack of a uniform definition of the

stress concept has made it difficult to integrate

stress-related findings and results. There are even

studies where researchers have equated stress with

specific emotional states such as anxiety, fear, or

anger (Lobel and Duknel-Schetter, 1990). Such

228

Nasiri Khoozani E. and Hadzic M. (2010).

HUMAN STRESS ONTOLOGY - Multiple Applications and Implications of an Ontology Framework in the Mental Health Domain.

In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 228-234

DOI: 10.5220/0002710402280234

Copyright

c

SciTePress

inconsistencies in the definition of stress have

culminated in ambiguous and inconsistent results in

terms of measurement of stress causes and effects, as

different researchers have adopted different

definitions for stress (Monroe, 2008). Therefore,

there is a fundamental need to clearly define

differential components of each definition within

their specified contexts and reach a consensual

conceptualization for stress-related concepts and

terms.

Secondly, there is a need to obtain a

comprehensive and cohesive view of all related

phenomena within our specified domain of

knowledge i.e. human stress, so that we can obtain a

better understanding of this phenomenon as well as a

perspective of gaps and issues observed in its

research field.

Thirdly, most current information resources

function autonomously. It means that contents in

certain information resources are developed, stored

and processed independently of other information

resources, making it difficult to elicit, in a precise

and integrative manner, all desirable information

embedded within various databases. Hence, there is

a need for the information resources to be equipped

with search engines with the capacity to look for the

meaning of information, and not merely be limited

to the appearance of a specific word in the text.

Current search engines perform keyword-based

searches which make the process of information

retrieval difficult and hinder the establishment of a

comprehensive and inclusive view of all related

phenomena within our specified domain of

knowledge. For example, a search for the term stress

theories in OvidSP database brings up more than

12900 results. This enormous number of results may

also include a large amount of data about unrelated

works and studies. Such a scattered collection of

data about stress theories would by no means offer

associations, interrelations, similarities, and

differences of related concepts and theories despite

the fact that all studies have elaborated on the same

phenomenon, have adopted or borrowed many

theory elements from one another, or are

explanatory, or contradictory to each other. In order

to introduce meaning and context into our search, we

firstly need to design an ontology. The search engine

will then use this ontology to provide meaning and

context for its searches.

Despite such issues and problems within its

research field, to the best of our knowledge, there is

no established ontology or ontology-based search

engine for the topic of human stress and its related

concepts. In this paper, we put forward the

significance of establishing Human Stress Ontology

(HSO) as a potential tool to address the

abovementioned issues. We will present a top-layer

model for the HSO which aims to capture and

represent all information related to stress, its causes,

mediators, effects, treatments, and measurements.

2 CHOICE OF THE ONTOLOGY

DESIGN METHODOLOGY

Ontology is defined as the formal and explicit

specification of a domain conceptualization (Gruber,

1993). In an ontology framework, formal refers to

knowledge representation that is mathematically

described and machine readable. A domain

conceptualization is an abstract model of a

phenomenon, i.e. an abstract view of domain

concepts and relationships among them, and explicit

expresses clear and precise definitions of concepts

and their relationships.

Ontologies were basically designed to facilitate

communication and interoperation between different

information systems by providing a formal, agreed

and shared framework for semantics of knowledge

domains used by those systems. The application of

ontologies within various communities such as

health and biomedical areas has proved effective and

operational (Ceusters et al., 2001).

It has been suggested that ontology building is

more a craft than a strict engineering design (Beck

and Pinto, 2002). There are different ontology

building methods which can be adopted for solving

different data management problems.

For the design of the HSO, we have chosen the

DOGMA method. The DOGMA methodology

(Spyns et al., 2008) represents a special paradigm

for separating the domain axiomatization (the

ontology base) from the application axiomatization

(the commitment layer) in order to solve the trade-

off problem observed between the usability and

reusability of an ontology. The DOGMA tool has the

capability to store basic concepts and their

application-specific constraints in two separate

layers: the ontology base and the commitment layer.

By means of the DOGMA tool, we will be able to

convert the elementary facts of concepts and their

relationships into the lexons which will be placed in

the ontology base. Lexons are formal binary facts

with the formal description of <Y: trem1 role1 co-

role2 term2>. The ontology commitment layer will

contain additional rules, restrictions and constraints

specified for the defined lexons. This advantage in

HUMAN STRESS ONTOLOGY - Multiple Applications and Implications of an Ontology Framework in the Mental Health

Domain

229

DOGMA allows domain experts and users to have

multiple views and requirements for different

applications while using the same stored meaning-

independent conceptualization (Spyns et al., 2008).

The DOGMA also offers the notion of the context as

an identifier to confine the interpretation of each

term to certain concepts within the context of that

term (Jarrar and Meersman, 2008).

The notion of context is of significance

particularly with regards to the maintenance of rules

and lexons. It has been argued that in the

maintenance phase of expert systems, the context

influences the rules provided by the experts. For

example, in the cases where there are inconsistent

interpretations of a set of data, it is the existence of

different rules in different contexts that create such

inconsistencies. Respectively, the context defines to

a large extent the way we answer a particular

question. This statement derives from the notion that

knowledge cannot be separated from the context and

efforts to reach context-free fundamentals of

knowledge are philosophically implausible

(Compton and Jansen, 1990).

However, there are some opposite views

maintaining that concepts should correspond to

reality and ontology relations such as Is-a or Part-of

can be established in a way that introduce real

physical relations in reality. According to this view,

high-quality ontologies are representations of reality

and they must incorporate universals that exist in the

real world of space and time (Smith, 2004).

This perspective though might be applicable in

scientific domains such as physics and biology

(where there are established scientific laws) its

application in abstract domains such as human stress

seems not to be realistic. In our work, we face a big

variety of theory-based definitions and explanations

for similar concepts where the extent to which they

represent real entities in the world is unknown and

arguable. For example, there are different theories to

explain how stressful life events contribute to states

of depression or other mental disorders, each

highlighting one particular aspect of those

phenomena. Or, it has been shown that during

different stages of development, the individual is

challenged by different types of stressors (Seiffge-

Krenke et al., 2009).

For this reason we have selected the DOGMA

methodology as it is important to provide a context

for the HSO concepts and their relationships. This

will be particularly appropriate for resolving the

abovementioned inconsistencies by classifying

concepts within the context of their relevant

theories, where a specified context identifier can

represent specific theories or explanations of the

same concepts. For example, stressful life events can

be classified according to the different contexts of

childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and elderly,

where each context is characterized by its own

instances of stressful life events.

3 THE HSO STRUCTURE

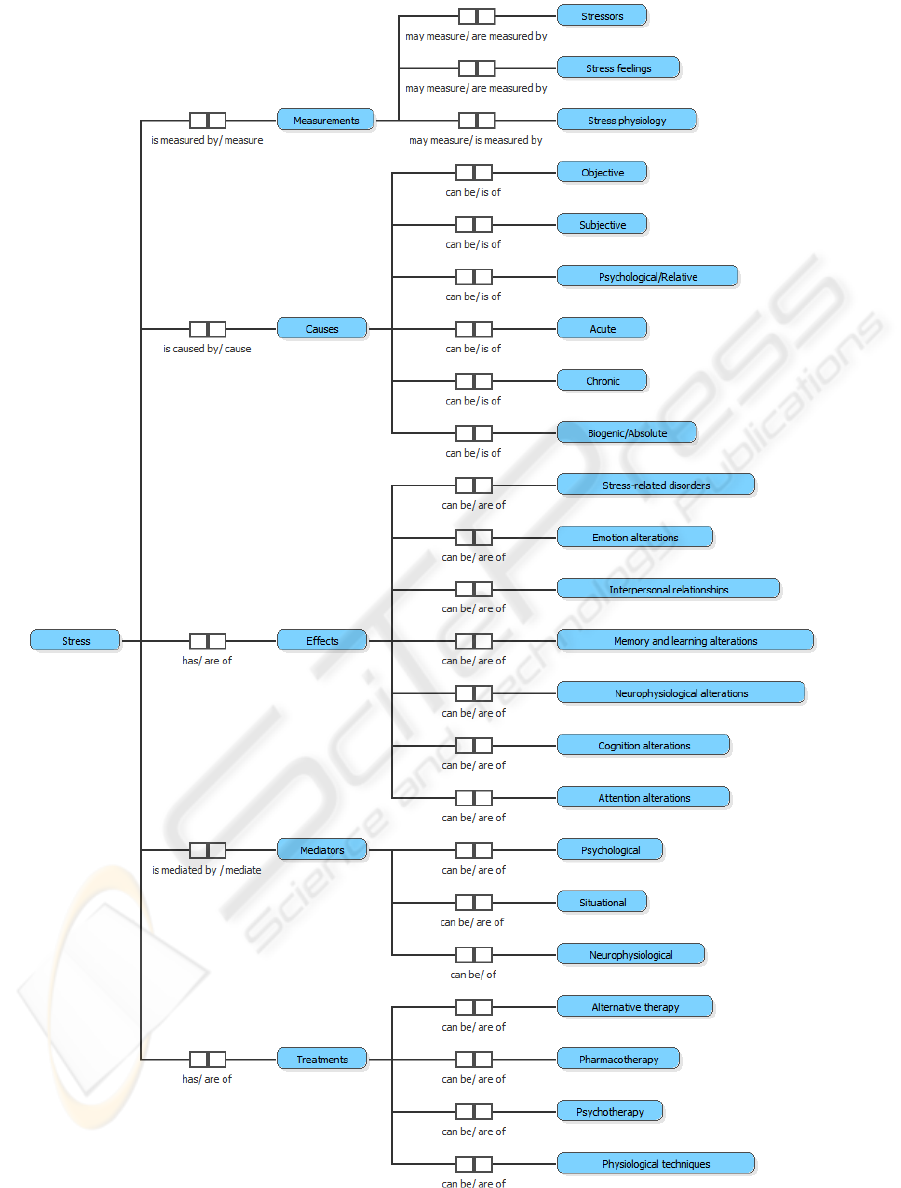

In this section, we present a graphical illustration of

the top-layer structure of the HSO plus a brief

explanation of its sub-ontologies and the observable

interrelationships existing among them.

The HSO consists of five sub-ontologies

including: 1. Stress Causes, 2. Stress Mediators, 3.

Stress Effects, 4. Stress Treatments, and 5. Stress

Measurements. All concepts which can be found

within the domain knowledge of human stress will

be placed under their related categories which fall

under the above sub-ontologies. Each sub-ontology

encapsulates its related categories and concepts;

however, the categories and concepts are not

mutually exclusive and there might be some

interrelations among them in certain contexts in

which they appear. Following, is a brief explanation

of each sub-ontology branch and some of their

defined categories. We will extend this ontology

model to incorporate all stress-related concepts and

theories.

3.1 Stress Causes (Stressors)

Overall, there are three general classifications for

stress-inducing factors regarding their relativity,

objectivity, and duration:

I. One classification system (Lupien et al., 2007)

classifies stressors into two groups based on their

relativity: a) Psychological (relative), and b)

Biogenic (absolute).

II. Another classification system (Pervin, 1978)

classifies stressors into two groups based on their

objectivity: a) Objective, and b) Subjective.

III. In one more popular division (Baum, 1990)

stressors are categorized into two groups according

to their duration: a) Acute, and b) Chronic.

3.2 Stress Mediators

The path from exposure to the stressor to stress

experience is not a direct path. In fact, a combination

of neurophysiological, psychological, and situational

factors mediates the link between stress causes stress

feelings, and consequent stress effects. We,

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

230

Figure 1: The top-level hierarchy of Human Stress Ontology (HSO) and its five sub-ontologies.

HUMAN STRESS ONTOLOGY - Multiple Applications and Implications of an Ontology Framework in the Mental Health

Domain

231

classify the stress mediators into the following three

categories with their corresponding sub-concepts:

I. Psychological mediators: a) Coping patterns,

b) Personality factors, c) Developmental factors, d)

Gender-related factors (Seiffge-Krenke et al., 2009),

and e) Cognitive factors (Sarafino, 1998).

II. Neurophysiological mediators: a) The HPA

axis, b) Limbic system reactions, c) Stress

hormones, and d) Stress-hormone receptors (Lupien

et al., 2007).

III. Situational mediators: a) Socioeconomic

factors, b) Cultural factors (Kopp et al., 1998a).

3.3 Stress Effects

The HSO classifies all functional and structural

stress-related alterations in the organism under seven

subclasses of: a) Stress-related disorders, b)

Neurophysiological alterations, c) Cognition

alterations, d) Emotion alterations (Lupien et al.,

2007), e) Learning and Memory (working,

declarative, emotional, long-term) alterations

(Lupein and McEwen, 1997), f) Attention alterations

(Ritter et al., 2007), and g) Effects on Interpersonal

relationships (Lindy, 1985).

3.4 Stress Treatments

Treatment of stress-related disorders draws on many

psychotherapy techniques, psychiatric interventions,

physiological techniques, and a wide range of

complementary therapies. These include: a)

Psychotherapy, b) Pharmacotherapy, c)

Physiological techniques, and d) Alternative

therapies (Everly and Lating, 2002).

3.5 Stress Measurements

If we are to effectively evaluate stress and its effects

on health, we need to correctly define the

fundamental variables of stress. Definition and

designation of such variables, as well as

experimental research on stress, necessitate the

design or creation of efficient measurement tools.

However, due to the existence of various

definitions for stress, inconsistent and superfluous

measurement tools for quantification of this

phenomenon have been created that consequently

resulted in phenomenological and methodological

mistakes. For example, some frequently used

instruments such as The Life Stressor Checklist-

Revised (Wolfe and Kimerling, 1998) focus more on

evaluating the stressors, not specifically addressing

other mediating factors which might affect the stress

response. Therefore, such measures do not measure

the stress response accurately (Everly and Lating,

2002).

In general, stress measurement tools can be

classified into three categories: a) Measurement of

stressors, b) Measurement of stress feelings, and c)

Measurement of physiology of stress response

(Everly and Lating, 2002).

4 EVALUATION OF THE HSO

For the evaluation of the HSO we will use the

conceptual coverage technique (Hartmann et al.,

2005) as follows: a test set (for example a set of 30

article abstracts randomly selected from various

psychology databases) will be used to evaluate the

designed ontology. The knowledge abstracted from

this test set will be encoded by means of the

designed ontology. Then, we will calculate the

percentage of sentences within this test set that can

be represented by the developed ontology.

Depending on the percentage of the covered text,

new concepts will be added and the created concepts

then will be further refined to ensure the HSO meet

criteria such as consistency, coherence, and

correctness.

Additionally, we have mapped the HSO to the

MeSH (Medical Subject Headings, 2008), the

National Library of Medicine's controlled

vocabulary thesaurus, to examine the degree to

which concepts in the HSO match the MeSH’s

stress-related concepts. Our mapping evaluation

demonstrated that for most concepts in the HSO,

there is no equal or even synonymous concept in the

MeSH as the MeSH is a generic medical thesaurus

and is not detailed enough to capture specific

knowledge domains such as human stress.

5 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE HSO

The HSO sub-ontologies have the potential to offer a

cohesive and coherent view of various stress-related

concepts. By considering the illustrated HSO figure,

some formerly unseen relationships among different

aspects of this phenomenon may be revealed,

motivating researchers to carry out additional studies

on these interesting and important topics.

Researchers can observe the interconnectedness of

different categories of stressors with multiple

aspects of stress response or stress mediators. For

example, the HSO suggests that there can be specific

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

232

links between biogenic stressors and cognitive

alterations which might be different from

associations between psychological stressors and

subsequent cognitive processes.

The HSO will potentially help identify and unify

the existing differences observed in definitions of

stress-related terms and concepts, representing

formal, elaborated, precise, and consensual

definitions for them, and thereby, facilitating

communication and interoperation across different

applications.

It will have the potential to provide an overview

of prominent research subjects such that different

subjects and concepts can be placed under their

appropriate categories and viewed as interrelated

and interwoven manifestations of one phenomenon,

i.e. human stress. Therefore, through the cohesive

and coherent structure of the HSO, some hitherto

unseen relationships among different aspects of

human stress may be revealed, motivating

researchers to carry out additional studies on

perceived gaps or other latent issues across entities

and theories. The HSO will also be a motivation for

the establishment of other ontologies in psychology

and psychiatry.

The HSO can be used to integrate heterogonous

information resources within the human stress

domain and manage contents of different databases

in relation to each other. It will facilitate

interoperability between different information

systems and enable the design of ontology-driven

software programs tools and semantic web engines

for intelligent access, management, retrieval, and

analysis of stress-related information.

The subsequently derived knowledge may also

help in the development of effective prevention and

intervention strategies in the field of mental heath.

Representation and description of various stress

causes, mediators, and their mechanisms in the form

of classified binary facts can facilitate the process of

formulating more evidence-based and effective

intervention strategies. Experts can store and

organize knowledge and scientific explanations of

the factors and mechanisms contributing to

causation and precipitation of stress-related

disorders in distinctive contexts according to their

underling theories. Different intervention and

treatment strategies, therefore, in the same fashion,

can be structured in their relevant contexts where

links between them, their underpinning theories, and

related pathological explanations can be

recognizable in an effective way. Given that

intervention strategies apply their effects differently

from situation to situation and individual to

individual, an HSO-based agent system is likely to

play an important role in defining the best treatment

technique for a specific situation or individual. This

will be possible by considering different situations

or personality characteristics as distinctive contexts

for which there are suggested or prescribed

treatment techniques available.

Another intriguing application of the HSO in the

mental health domain relates to its potential for

facilitating the establishment and implementation of

various stress-related psychometric tests and

inventories. By obtaining consensual and shared

definitions of stress-related concepts and terms,

researchers and clinicians will gain a more coherent

and realistic understanding of what exactly they aim

to measure. For example, current differences and

disagreements on whether a certain test measures

stress responses, stress feelings, or stress-inducing

factors are likely to be resolved by linking each item

of the test to their relevant conceptualizations

embedded in the ontology framework. The context-

based binary facts in the HSO can be used as a basis

for development of more valid stress-related

psychological tests and inventories. For example,

test inventors aiming to capture specific test-items

for measurement of stress-response will acquire a

more accurate and consensual view of relevant items

by mapping those items to their formal definitions in

their related contexts within the HSO. In this way,

obscure, intrusive, or irrelevant items such as stress-

stimuli measuring items can be recognized and

separated out by juxtaposing them with items in

targeted contexts. This application of the HSO can

be an intriguing progress in the process of test

invention and validation in psychology, psychiatry,

and mental health domains in general. On this

ground, we will also be able to develop specific

intelligent agents to practise the process of test

invention and validation in an automated way. For

instance, an automated agent as such may have the

potential to help researchers calculate the degree to

which a certain test is related to a specified concept.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we explained the significance, possible

applications, and implications of the Human Stress

Ontology (HSO) for the mental health domain. The

HSO will facilitate intelligent retrieval and analysis

of stress-related information. This ontology

framework is likely to help researchers increase their

understanding of the related concepts, their

definitions and possible associations in various areas

HUMAN STRESS ONTOLOGY - Multiple Applications and Implications of an Ontology Framework in the Mental Health

Domain

233

of stress-related research by discovering some

formerly unseen relationships among different

aspects of this phenomenon.

We also highlighted the significant role of

context-based conceptualization and classification of

stress-related phenomena for various psychological

test invention and validation purposes, as well as

intervention and prevention strategies. It was

suggested that the notion of context in the HSO

framework may resolve the problem of having

different theories, definitions, and explanations for

similar concepts within the domain of human stress.

We are in the process of introducing ontology as

an auxiliary and complementary method to mental

health research and study. The HSO project can be

considered as the emergence of a new method in

psychology and psychiatry research, inspiring

researchers to consider ontology as an effective tool

for studying various topics of those areas of science

and art. Our future work on the application of the

HSO in psychometrics and intervention strategies is

expected to have significant implications for mental

health researchers and clinicians.

REFERENCES

Baum, A. (1990). Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic

distress. Health Psychology, 9(6), 653-75.

Beck, H., and Pinto, H. S., (2002). Overview of

approaches, methodologies, standards and tools for

ontologies. The agricultural ontology service.

Ceusters, W., Martens, P., Dhaen, C., and Terzic, B.

(2001). LinkFactory: an advanced formal ontology

management system. Proceedings of Interactive Tools

for Knowledge Capture Workshop, Canada. KCAP.

Compton, P., and Jansen, R. (1990). A philosophical basis

for knowledge acquisition. Knowledge Acquisition, 2,

241-257.

Everly, G. S., Jr. and Lating, J. M. (2002). A clinical guide

to the treatment of the human stress response (2

nd

edition). Plenum publishers.

Gruber, T. R. (1993). A translation approach to portable

ontology specifications. Knowledge acquisition, 5,

199-220.

Harris, T. (1991). Life stress and illness: The question of

specificity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 211-

219.

Hartmann, J., Spyns, P., Giboin, A., Maynard, D., Cuel,

R., Carmen Suarez-Figueroa, M., and Sure, Y. (2005).

D1.2.3 Methods for Ontology Evaluation. Knowledge

Web Consortium.

Jarrar, M., and Meersman, R. (2008). Ontology

Engineering - The DOGMA Approach. In Chang, E.,

Dillon, T., Meersman, R., and Sycara, K.(Eds),

Advances in Web Semantic, A state-of-the Art

Semantic Web Advances in Web Semantics IFIP2.12.

Chapter 3. Springer.

Kopp, M. S., Skrabski, Á., and Szedmák, S. (1998a).

Socioeconomic differences and psychosocial aspects

of stress in a changing society. Annals of the New York

Academy of Science, 851, 538-543.

Lifeline Australia. (2008). Retrieved 25 April 2009, from

http://www.lifeline.org.au/learn_more/media_centre/m

edia_releases/2008/stressed_out_australia_-

_survey_sparks_call_for_urgent_change.

Lindy, J. D. (1985). The trauma membrane and other

clinical concepts derived from psychotherapeutic work

with survivors of natural disasters. Psychiatric Annals,

15, 153-160.

Lobel, M., and Dunkel-Schetter, C. (1990).

Conceptualizing stress to study effects on health:

environmental, perceptual, and emotional components.

Anxiety Research, 3, 213-230.

Lupien, S. J., Maheu, F., Tu, M., Fiocco, A., and

Schramek, T. E. (2007). The effects of stress and

stress hormones on human cognition: Implications for

the field of brain and cognition. Brain and Cognition,

65, 209-237.

Lupein, S. J., and McEwen, B. S. (1997). The acute effects

of corticosteroids on cognition: Integration of animal

and human model studies. Brain Research Reviews,

24(1), 1-27.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). (2008). Accessed on

the 20

th

of August 2009 from

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/.

Monroe, S. M. (2008). Modern approaches to

conceptualizing and measuring human life stress,

Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 33–52.

Pervin, L. A. (1978). Definitions, measurements, and

classifications of stimuli, situations, and environments.

Human Ecology, 6, 71-105.

Ritter, F. E., Reifers, A. L., Klein, A. C. and Schoelles, M.

J. (2007). Lessons from defining theories of stress. In

Gray, W. (Ed.) Integrated Models of Cognitive

Systems. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sarafino, E. P. (1998). Health psychology:

Biopsychosocial interactions (3

rd

ed). New York:

Wiley.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., Aunola, K., and Nurmi, J. (2009).

Changes in stress perception and coping during

adolescence: The role of situational and personal

factors. Child Development, 80(1), 259-279.

Smith, B. (2004). Beyond concepts: ontology as reality

representation, In Formal Ontology and Information

Systems, Amsterdam: IOS Press, 73-84.

Spyns, P., Tang, Y., and Meersman, R. (2008). An

ontology engineering methodology for DOGMA.

Journal of Applied Ontology, 1-2 (3), 13-39.

Wolfe, J., and Kimerling, R. (1998). Assessment of PTSD

and gender. In Wilson, J., and Keene, T. M., (Eds).

Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New

York: Plenum.

HEALTHINF 2010 - International Conference on Health Informatics

234