STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF WEB-BASED TUTORIALS

AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELF REGULATED

LEARNING AND LEARNING PERFORMANCE

USING WEB-BASED TUTORIALS

Swati Nere and Eugenia Fernandez

Purdue School of Engineering & Technology, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis

799 W. Michigan St., ET 301, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.

Keywords: Self-efficacy for Self regulated Learning, Web-based Tutorials, Learning Styles.

Abstract: This study was designed to examine the effectiveness of Web Based Tutorials (WBTs) and the correlation

between students’ self efficacy score for self regulated learning and their learning performance using WBTs.

Participants were graduate students (N = 14) enrolled in a statistics course during a single semester. The

results of this study showed that WBTs were effective for learning statistics concepts. However, there was

no correlation between students’ self efficacy score for self regulated learning and their learning

performance using WBTs. Additional investigation showed that the classroom instruction mode was more

effective than the WBT instruction.

1 INTRODUCTION

Distance education is a rapidly growing medium that

is used in almost every field for training and

education. This is due to its basic advantages,

namely convenience, learning at one’s own pace,

and around-the-clock online accessibility. Web-

based tutorials (WBTs) have become an important

and integral part of distance education (Davidson-

Shivers & Rasmussen, 2006).

Research has shown that effective use of WBT

and multimedia can increase student learning

(Forsyth & Archer, 1997; Kazmerski & Blasko,

1999; Liu, 2004; Mackey & Jinwon, 2008) and help

students to understand complex concepts that

sometimes are difficult to understand in a face-to-

face class setting due to time limitations. Thus, it is

clear that computer-based demonstrations and

tutorials may prove beneficial to students’ learning

in a course.

Students’ academic success is also related to

their use of self-regulation strategies. In educational

literature, it is often referred to as Self-Efficacy for

Self-Regulated Learning (SESRL, henceforth

referred as SRL). It is a relatively new area in social

cognitive learning theory. SRL is a comprehensive

construct that focuses on students’ performance and

achievement of learning processes in educational

settings by focusing on how students motivate, plan,

monitor, and evaluate personal progress

(Zimmerman, 1989).

This research investigates the effectiveness of

WBTs and the relationship between students’ self-

regulation strategies and their learning through

WBTs.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

In face-to-face class instruction, it can become

difficult for students to learn complex concepts due

to time limitations. Statistics is an example of a

course that involves learning many complex

concepts and procedures. In such cases, WBTs can

be used as an supplemental tool, providing out-of-

classroom instruction to enhance conceptual

learning.

Despite the many advantages web-based tutorials

offer, they can pose problems associated with a lack

of SRL skills. SRL skills include goal setting, self-

monitoring, self evaluation, use of learning

strategies, help seeking, and time planning and

19

Nere S. and Fernandez E. (2010).

STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF WEB-BASED TUTORIALS AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELF REGULATED LEARNING AND

LEARNING PERFORMANCE USING WEB-BASED TUTORIALS.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 19-26

DOI: 10.5220/0002774800190026

Copyright

c

SciTePress

management (Zimmerman, 2008). Learning through

WBTs is student-centered in that students must

practice self-regulatory skills to accomplish their

learning goals (Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2003). It is

expected that experienced students regulate their

own learning skilfully. However, many often stick to

high school or grade school learning strategies that

prove to be insufficient to the college environment

(Hofer, Yu, & Pintrinch, 1998).

Secondly, although online classes and web-based

tutorials are part of distance education, they have

some differences. Online classes make use of

synchronous/asynchronous communication tools like

chat, email, and forums. On the other hand, web-

based tutorials typically involve one shot exposure,

require shorter learning span, and don’t have

facilities where students can participate in

synchronous/asynchronous communication.

Lastly, while there is an ample research on SRL,

less research (Beile & Boote, 2004) has been done in

relation to WBTs. In view of this, research is

necessary to determine if WBTs are effective in

students’ understanding of higher level concepts and

whether students’ performance in WBT learning is

related to their self-regulation strategies.

The research on the effectiveness of WBTs

shows that students are satisfied with learning

through WBTs (Aberson, Berger, Emerson, &

Romero, 1997, 2007; Bliwise, 2005; Buzzell,

Chamberlain, & Pintauro, 2002; Daeid, 2001;

Donovan & Nakhleh, 2007; Michel, 2001; Nedic &

Machotka, 2006; Wilson & Harris, 2002;). Belawati

(2005) found that students’ participation in online

tutorials improves course completion rates and

achievement. In view of this, the outcome of this

study will be helpful in the design of more WBTs for

conceptual learning of the difficult topics in

statistics. With the knowledge construction provided

through WBTs, classroom time can effectively be

used on the application of the concepts.

Student self-efficacy for self-regulated learning

is becoming an interesting area of research in

educational literature. Zimmerman (1994) has

shown that self-regulation is a reliable predictor of

academic performance. According to Zimmerman

(1990), self-regulated learning theories of academic

achievement are distinct from other means of

learning due to two main reasons, namely how

students select, organize, or create beneficial

learning environments for themselves, and how they

plan and control the form and amount of their own

instructions. Zimmerman (1990) has concluded in

his overview study of SRL and academic

achievement that systematic efforts can be launched

to teach self-regulation to students who approach

learning passively. According to Zimmerman

(1990), “A self-regulated learning perspective on

students’ learning and achievement is not only

distinctive, but it has profound implications for the

way teachers should interact with students and the

manner in which schools should be organized (p.4).

Accordingly, it is important to know the relationship

between SRL and students’ learning performance

using WBTs.

The main purpose of this study is to determine

the effectiveness of web-based tutorials for

understanding statistical concepts and examine the

relationship between students’ SRL and their

learning performance using WBTs. More

specifically, the objective of the study is to seek

answers to the following research questions:

1. Is a web-based tutorial effective in helping

students understand difficult concepts in

statistics?

2. Is there any difference between students’

learning using WBT instruction and classroom

instruction mode?

3. Is there any relationship between students’ SRL

and their WBT learning performance?

4. Are students’ SRL independent of their learning

style?

5. How satisfied are students with learning using

WBTs?

By participating in this study, students will

increase their awareness of their SRL strategies.

Results of the study will provide insight to both

students and teachers on how to improve and

stimulate SRL strategies respectively.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

A growing body of research exists on the

effectiveness of learning and teaching through

WBTs. Most of these studies compare online and

face-to-face learning approaches. Some of this

research shows that WBTs are more effective than

classroom instruction while others show that WBTs

are as effective as classroom instruction. For

example, researchers (Aivazids, Lazaridou, &

Hellden, 2006; Day, Raven, Newman, 1998; Melara,

1996) found that web-based tutorials can accelerate

the learning process with the same level of

achievement as a classroom lecture. O’Neal, Jones,

Miller, Campbell, and Pierce (2007) showed that

web based instruction is as effective as traditional

teaching for disseminating special education course

content to pre-service teachers. Fernandez (1999)

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

20

found no significant difference in learning through a

classroom lecture and using a web-based tutorial.

Similar results were found in a study by Nichols,

Shaffer, and Shockey (2003) which compared

student learning through an online tutorial to a

traditional lecture and also found that students were

satisfied with online instructions. Belawati (2005)

found that students’ participation in online tutorials

improves course completion rates and achievement.

Sweeney, O’Donoghue and Whitehead (2004)

suggested that a balance is needed between face-to-

face and web-based tutorial learning approaches.

The effectiveness of WBTs has been investigated

in almost every subject, for example, chemistry

(Donovan & Nakhleh , 2007), engineering (Nedic &

Machotka, 2006), library sciences (Michel, 2001),

forensic science (Daeid, 2001), medical science

(Buzzell, Chamberlain, & Pintauro, 2002), and

psychology (Wilson & Harris, 2002). All of these

studies found that WBTs are as effective as

classroom instruction.

Aberson, Berger, Emerson, and Romero (1997,

2007), and Bliwise (2005) explored the effectiveness

of WBTs for difficult to understand statistics

concepts. All these researchers found that students

were more satisfied with WBT learning and hence

attempts were made to improve the learning through

the design of more WBTs.

Recent research related to SRL shows that SRL

is one of the reliable factors that can be linked to

personal and academic achievement of students.

Zimmerman and Martinez-Pons (1988) developed a

structured interview procedure that involved a

number of contexts or descriptions of instructional

problems that students often encounter. In analysis,

the researchers identified 14 self-regulated learning

strategies, namely self evaluation, organization and

transformation, goal setting and planning,

information seeking, record keeping, self-

monitoring, environmental structuring, giving self-

consequences, rehearsing and memorizing, seeking

social assistance, and reviewing (notes, books or

tests). After studying the responses of 40 students

from advanced academic track and 40 students from

lower academic track, the researchers found that

students’ use of self-regulated learning strategies

was strongly associated with their superior academic

functioning.

SRL has been validated by Usher and Pajares

(2006) in which Bandura’s Children Self-Efficacy

Scale was assessed on a sample of 3,760 students

from grade 4 to 11. The scale formed a one-

dimensional construct and demonstrated an

equivalent structure for boys and for girls, and for

elementary, middle, and high school students. Thus,

the scale provided a sound measure with which

researchers can continue to assess students’ beliefs

about their self-regulatory capabilities.

Although, there is ample research on self-

efficacy and SESRL, less research has been done in

relation with WBTs (Beile & Boote, 2004). Dabbagh

and Kitsantas (2004) point out that Web-based

learning approaches are students-centered and web-

based learning tools like emails, forums and chat can

support students’ development of self-regulatory

skills that are essential for success in student-

centered web-based learning environments.

The area of learning styles (the way a person

takes in, understands, expresses and remembers

information) has also been largely explored by

educational researchers. For example, Marrison and

Frick (1994) showed that academic achievement is

affected by one’s learning style. Diaz and Cartnal

(1999) found that online students were more

independent and on-campus students were more

dependent in their styles as learners.

Mupinga,

Nora, and Yaw (2006) suggest that the design of

online learning activities should strive to

accommodate multiple learning styles. Garland and

Martin (2005) examined the differences between the

learning styles of 168 students in online and

traditional face to face courses and found a

significant difference: “the learning style of the

online student as a group was assimilating, while the

learning style of the face-to-face student as a group

was diverging” (p. 73). They also found a

significant relationship between male students with

an Abstract Conceptualization learning mode and

student engagement. The authors concluded that the

learning style and gender of all students must be

considered when designing online courses. In view

of this, the present paper also investigates the

relationship between students’ SRL and their

learning style.

4 ASSUMPTIONS &

DELIMITATIONS

This study assumed that all participants were able to

navigate through course management systems, and a

Windows-based operating system, and had a basic

knowledge of how to navigate a WBT.

The scope of this study was limited to the

learning of four statistics concepts taught in a single

graduate class, namely z test for single group, chi-

square, independent samples t-test, and correlated

samples t-test.

STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF WEB-BASED TUTORIALS AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELF

REGULATED LEARNING AND LEARNING PERFORMANCE USING WEB-BASED TUTORIALS

21

5 METHODOLOGY

The participants in this study consisted of graduate

students enrolled in a semester long graduate

research methods and statistics course at a large

Midwestern public university. Students were

informed of the purpose of the study and completed

an informed consent agreement.

This study used a single group pre-test post-test

repeated measures quasi-experimental design to

(1) evaluate the effectiveness of web-based tutorials

for learning statistical concepts using classroom

teaching as a control group, and (2) to investigate the

relationship between students’ learning performance

using WBT and their SRL.

Two pairs of related statistical concepts were

selected – z test/Chi square goodness of fit test and

independent-groups/correlated-groups t tests. WBTs

were designed for two of these statistical concepts:

z-test for single group and t- test for independent

groups, referred to as WBT-1 and WBT-2

respectively. The two WBTs can be viewed at

https://dnet.cit.iupui.edu/wbt1/index.htm and

https://dnet.cit.iupui.edu/wbt2/index.htm

respectively. The other two concepts (Chi-square

and t-test for correlated groups) were taught using

classroom instruction. These two topics were used as

a control group for the related experimental

components.

Gagné and Briggs (1979) have emphasized that

in order to implement an effective learning process,

it is important to evaluate students’ understanding of

the concepts as well as to get the feedback from

students during evaluation. In view of these

suggestions, a pre-test was administered prior to the

start of each concept mentioned above. Due to the

timing of the concepts in the course, the pre-tests for

the z test and Chi square were combined as were the

pre-tests for the independent-groups and correlated-

groups t tests. After each concept’s learning

exposure, a post-test was administered. A

difference score (post-test – pre-test) was then

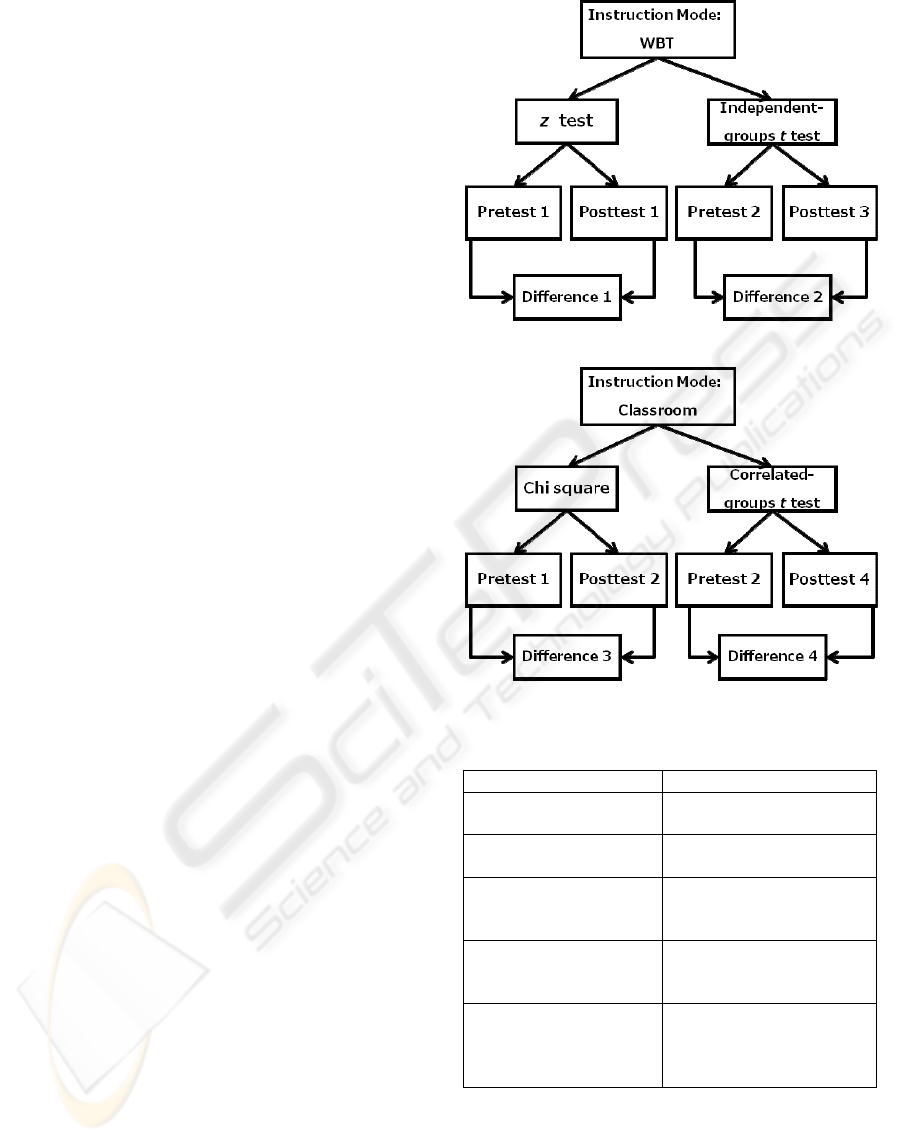

computed for each concept. Figure 1 provides a

graphical representation of this procedure. Table 1

shows how each change score was used.

Riel and Harasim (1994) have suggested that

user feedback is one way of examining if the

learning environment is successful in meeting

learning outcomes. In view of this, a tutorial

satisfaction questionnaire was used at the end of the

two post-tests for topics taught using WBTs.

Student’s learning style was determined by

administering one of the most widely used online

questionnaires, Keirsey Temperament Sorter II

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the methodology.

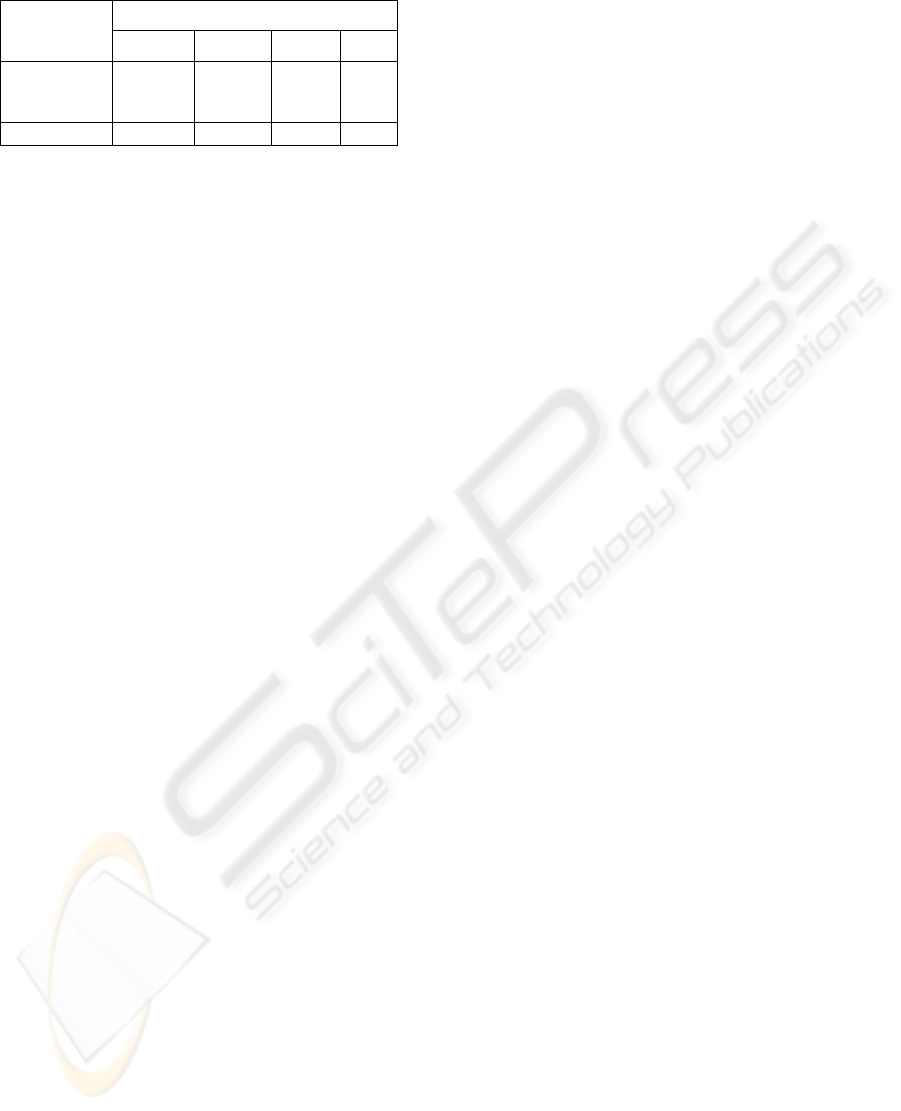

Table 1: Use of change scores.

Measure Used to Evaluate

Difference 1

Effectiveness of WBT on

z test

Difference 2

Effectiveness of WBT on

independent-groups t test

Difference 3

Effectiveness of

classroom instruction on

Chi square goodness of fit

Difference 4

Effectiveness of

classroom instruction on

correlated-groups t test

Difference 1 –

Difference 3 and

Difference 2 –

Difference 4

Effectiveness of WBT vs.

classroom instruction

(Keirsey, n.d). The learning style, demographic

survey, and students’ SRL scale were administered

prior to the start of any experimental components.

The students’ self regulation strategies were

evaluated using one subscale from the Children’s

Multidimensional Self-Efficacy Scales, namely self-

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

22

efficacy for self- regulated learning. The scale

included 11 items that measures students’ perceived

capability to use a variety of self-regulated learning

strategies. Students’ responses were recorded

according to a 7-point scale ranging from not well at

all for a rating of 0, not too well for 3, pretty well for

5, and very well for 7. Students’ SRL was calculated

by adding the score of 11 items for each students and

then taking an average of that score, as has been

done in other studies (Carroll & Garavalia, 2002;

Inzlicht, McKay, & Aronson, 2006). As discussed

in the literature review, the SRL scale has been

validated by Usher and Pajares (2006).

6 RESULTS

Of the 19 students enrolled in the course, 14 (57%

male, 43% female) usable responses were obtained.

Students who participated in the study but didn’t

complete both pairs of pre-tests and post tests were

excluded from the data analysis. The majority of the

students (50%) were of age group 25-34 years old

followed by age group of 45 and over. 36% of the

participants were full time students while 64% were

part time students.

6.1 Hypothesis 1

Is a WBT effective in helping students understand

the concepts in statistics?

A paired-samples t test was calculated to

compare the mean pre-test score before the exposure

to learning through WBT-1 to the mean post-test

score after the WBT-1 learning. The mean on the

pre-test was 24% (sd =11.87), and the mean on the

post-test was 67% (sd = 23.60). A significant

increase from pre-test to post-test was found (t (8) =

5.768, p < .001).

A paired samples t test was calculated to

compare the mean pre-test score before the exposure

to the learning through WBT-2 to the mean post-test

score after the WBT-2 learning. The mean on the

pre-test was 10% (sd =20.69), and the mean on the

post-test was 65% (sd = 18.57). A significant

increase from pre-test to post-test was found (t (8) =

6.805, p < .001).

6.2 Hypothesis 2

Is there any difference between students’ change in

knowledge after WBT learning and classroom

learning?

A paired-samples t test was calculated to

compare the mean change in knowledge after

learning through WBT-1 to the mean change in

knowledge after classroom instruction on Chi

square. The mean change in knowledge after

learning through WBT-1 was 46% (sd =21.26), and

the mean change in knowledge after classroom

instruction was 77% (sd = 19.80). A significant

difference was found (t (7) = -3.037, p < .05).

Students learned more after classroom instruction

than using the WBT-1.

A paired-samples t test was calculated to

compare the mean of change in knowledge after

learning through WBT-2 to the mean change in

knowledge after classroom instruction. The mean

change in knowledge after learning through WBT-2

was 45% (sd =31.38), and the mean change in

knowledge after classroom instruction was 65% (sd

= 20.18). A significant difference was found (t (10)

= -2.541, p < .05). Students learned more after

classroom instruction than using the WBT-2.

6.3 Hypothesis 3

Is there any correlation between students’ SRL and

their WBT performance?

A Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated

for the relationship between students’ SRL and their

WBT-1 performance. A moderate correlation that

was not significant was found (r (7) = .441, p > .05).

Students’ SRL was not strongly related to their

WBT-1 performance.

A Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated

for the relationship between students’ SRL and their

WBT-2 performance. A moderate correlation that

was not significant was found (r (9) = .027, p > .05).

Students’ SRL was not strongly related to their

WBT-2 performance.

6.4 Hypothesis 4

Are students’ SRL independent of their learning

style?

Only 11 of the 14 students completed the Kiersey

Temperament Sorter, with 8 of the 11 falling into the

Guardian temperament. Because of this clustering,

an ANOVA comparing students’ SRL by

temperament type was not possible. For reporting

purposes the SRL scores were divided into three

categories: high (SRL > 4), medium (SRL =4) and

low (SRL < 4). Table 2 shows the cross tabulation

between SRL level and students’ Keirsey

temperament.

STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF WEB-BASED TUTORIALS AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELF

REGULATED LEARNING AND LEARNING PERFORMANCE USING WEB-BASED TUTORIALS

23

Table 2: Count of SRL by Temperament.

Temperament

Guardian Rational Idealist Total

SRL

Med. 1 0 0 1

High 8 1 1 10

Total 9 1 1 11

6.5 WBT Satisfaction

How satisfied are students with their change in

knowledge using WBTs?

11 out of 14 participants responded to the

satisfaction questionnaire. 45% of the students were

‘somewhat satisfied’ with WBTs while 36% were

neutral about it. Two participants were dissatisfied

with the tutorial. Satisfied students liked the

content/information presented in the WBT while the

dissatisfied students reported lack of interactive

features and necessity of more illustrative examples.

A total of 60% of the respondents said they would be

‘likely’ to study similar tutorials. None of the

students reviewed any other resources on the topic

taught using WBT-1 and WBT-2.

7 LIMITATIONS

No web-tracking software was used so the time

spent studying the tutorial was not measured.

However, the students were asked in the feedback

questionnaire about how much time they spent

studying the tutorial. A survey method was used to

determine the students’ satisfaction about their

change in knowledge after learning through the web-

based tutorial. A major limitation of the survey

method is that it relies on a self-report method of

data collection. In addition, factors like poor

memory, intentional deception, or misunderstanding

of the question may all contribute to inaccuracies in

the data. Some of the responses for the tutorial

satisfaction questionnaire were inconsistent. The

pre-test and post-tests questions were not face

validated. The small sample size in this study is an

obstruction to the issue of generalizing the findings

to larger populations. And hence the results of this

study cannot be generalized.

8 CONCLUSIONS

The result for the first hypothesis, which

investigated the effectiveness of WBTs for

understanding statistics concepts, showed that there

was a significant increase in students’ change in

knowledge using WBT learning. This result is

consistent with the literature that shows WBTs are

just as effective a learning medium as classroom

instruction (Buzzell, Chamberlain, & Pintauro, 2002;

Daeid, 2001; Donovan & Nakhleh , 2007;

Fernandez, 1999; Michel, 2001; Nedic & Machotka,

2006; Wilson & Harris, 2002). More specifically, it

confirms that WBTs were effective for learning

statistics concepts, similar to studies by Aberson,

Berger, Emerson, and Romero (1997, 2007), and

Bliwise (2005). However, our results were

influenced by the uncontrollable confound of

students reading the textbook chapter before the

WBT exposure. 64% (7/11) and 67% (8/12) students

read/skimmed through the textbook chapter before

they studied WBT-1 and WBT-2 respectively.

The outcome of the second hypothesis, which

examined the learning differences between WBTs

classroom instruction, showed that the classroom

instruction was more effective than WBT

instruction. This is probably due to the fact that the

pair of topics taught through WBTs and classroom

instructions were comparable. In both situations, the

WBT topic was introduced first and then the related

topic was taught using classroom instruction. This

design might have prepared the students’ mindset

first through the WBT and repetition may have

helped them understand the second topic in the

classroom setting more easily. In view of this, future

studies should investigate the change in knowledge

by reversing this sequence. However, coupled with

the results of the first hypothesis, it is safe to say that

this research validates the use of WBTs as a

supplemental method of instruction. By moving

some of the instruction out of the classroom, it could

free classroom time for the practical applications of

those concepts.

The consequence of the correlation test between

SRL and WBT performance was interesting. In the

present study, the majority of the students were of

age 25-34 and above 45. Generally, this group is

considered as experienced students and hence

exhibited high SRL score. However, their WBT

performance didn’t indicate a proportional increase,

demonstrating no correlation between SRL and

WBT performance. This may be attributed to no

face validation of the test questions or possible

reluctance or lack of motivation to learn using WBT

as the participants were from an on-campus class.

Some students reported that they didn’t study the

tutorial (27% and 33% students did not study WBT-

1 and WBT-2 respectively), which may indicate

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

24

their lack of motivation to learn using WBT and

respond to related post-tests as compared to their

class work. In future replication of such study, due

consideration may be given to add students’ post-test

score to their final course grade in order to motivate

students so as to improve the response rate. Some

students reported that the WBTs lacked interactive

features. In view of this, in the future replication of

such a study, it would be helpful to determine what

interactive features are desirable and then design the

WBTs accordingly.

The sample size in the present study was small

and the participants were graduate students who

exhibited high SRL score. Undergraduate students

are more likely to stick to their high school learning

strategies which are not sufficient for the college

learning. It would be interesting to replicate this

study with undergraduate students enrolled in on

campus and online classes and give WBT learning

treatment to both groups.

Student satisfaction with the WBTs was mild due

to their desire for more interactive features and

illustrative examples. This speaks to the high level

of expectations on the part of the students for online

materials. Thus, this research has shown that WBTs

do have value and can be used as a supplement to

classroom teaching, but they should be designed to

include interaction.

REFERENCES

Aberson, C. L., Berger, D. E., Emerson, E. P., & Romero,

V. L. (1997). WISE: Web interface for statistics

education. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments,

& Computers, 29(2), 217-221.

Aberson, C. L., Berger, D. E., Emerson, E. P., & Romero,

V. L. (2007). Evaluation of an interactive tutorial for

teaching hypothesis testing concepts. Teaching of

Psychology, 30(1), 75-78.

Aivazids, C., Lazaridou, M., & Hellden, G.F. (2006). A

comparison between a traditional and an online

environmental educational program. The Journal of

Environmental Education, 34(4), 45-54.

Beile, P. M., & Boote, D. N. (2004). Does the medium

matter? A comparison of a web-based tutorial with

face-to-face library instruction on education students'

self efficacy levels and learning outcomes. Research

Strategies, 20(1-2), 57-68.

Belawati, T. (2005). The impact of online tutorials on

course completion rates and student achievement.

Learning, Media and Technology, 30(1), 15–25.

Bliwise, N. G. (2005). Web-based tutorials for teaching

introductory statistics. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 33(3), 309-325.

Buzzell, P. R., Chamberlain, V. M., & Pintauro, S. J.

(2002). The effectiveness of web-based, multimedia

tutorials for teaching methods of human body

composition analysis. Advances in Physiology

Education, 26, 21-29.

Carroll, C. A, & Garavalia, L.S. (2002). Gender and racial

differences in select determinants of student success.

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 66,

382-387.

Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (2003). Do web-based

pedagogical tools support self-regulatory processes in

distributed learning environments? Paper presented in

American Educational Research Association (AERA),

Chicago, Illinois.

Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (January-March, 2004).

Supporting self-regulation in a student-centered Web-

based learning environments. International Journal of

E-Learning, 40-47.

Daeid, N. N. (2001). The development of interactive

World Wide Web based teaching material in forensic

science. British Journal of Educational Technology,

32(1), 105-108.

Davidson-Shivers, G. V., & Rasmussen, K. L. (2006).

Web-based learning design, implementation and

evaluation. N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Day, T. M., Raven, M. R., & Newman, M. E. (1998). The

effects of World Wide Web instruction and traditional

instruction and learning styles on achievement and

change in student attitudes in a technical writing in an

agricommunication course. Journal of Agricultural

Education, 39(4), 65-75.

Diaz, D. P., & Cartnal. R. B. (1999). Students' learning

styles in two classes: Online distance learning and

equivalent on-campus. College Teaching, 47

(4), 130-

135.

Donovan, W., & Nakhleh, M. (2007). Student use of web-

based tutorial materials and understanding of

chemistry concepts. The Journal of Computers in

Mathematics and Science Teaching, 26(4), 291-327.

Fernandez, E. (1999). The effectiveness of Web-based

tutorials. Proceedings of the Sixteenth International

Conference on Technology and Education, Edinburgh,

Scotland, March 28-31, 268-270.

Forsyth, D. R., & Archer, C. R. (1997). Technologically

assisted instruction and student, mastery, motivation,

and matriculation. Teaching of Psychology, 24, 207-

212.

Gagné, R. M., & Briggs, L. J. (1979). Principles of

Instructional Design (2

nd

ed.). New York, NY: Holt,

Rinehart and Winston.

Garland, D., & Martin, B. N. (2005). Do gender and

learning style play a role in how online courses should

be designed? Journal of Interactive Online Learning,

4(2), 67-81.

Hofer, B. K., Yu, S. L., & Pintrinch, P. R. (1998).

Teaching college students to be self-regulated learners.

In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Self-

regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective

practice (pp. 57-85). New York: Guilford.

STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF WEB-BASED TUTORIALS AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELF

REGULATED LEARNING AND LEARNING PERFORMANCE USING WEB-BASED TUTORIALS

25

Inzlicht, M., McKay, L., & Aronson, J. (2006). Stigma as

ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice

affects self-control. Association for Psychological

Science 17(3), 262-269.

Kazmerski, V. A., & Blasko, D. G. (1999). Teaching

observational research in introductory psychology:

Computerized and lecture-based methods. Teaching of

Psychology, 26, 295-298.

Keirsey, D (n.d.). Keirsey.com Retrieved July 22, 2008

from http://www.keirsey.com/

Liu, L. (2004). Web-based resources and applications:

Quality and influence. Computers in the Schools,

21(3/4), 131-47.

Mackey, T. P., & Jinwon, H. (2008). Exploring the

relationships between Web usability and students'

perceived learning in Web-based multimedia

(WBMM) tutorials. Computers & Education, 50(1),

386-409.

Marrison, D. L., & Frick, M. J. (1994). The effects of

agricultural students’ learning styles on academic

achievement and their perception of two methods of

instruction. Journal of Agricultural Education, 35(1),

26-30.

Melara, G. E. (1996). Investigating learning styles on

different hypertext environments: Hierarchical-like

and network-like structures. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 14(4), 313-328.

Michel, S. (2001). What do they really think? Assessing

student and faculty perspectives of a Web-based

tutorial to library research. College & Research

Libraries, 62(4), 317-332.

Mupinga, D. M., Nora. R.T., & Yaw, D. C. (2006). The

learning styles, expectations, and needs of online

students. College Teaching, 54(1), 185-194

Nedic, Z., & Machotka, J. (2006). Interactive electronic

tutorials and web based approach in engineering

courses. Proceedings of the 5th IASTED international

conference on Web-based education Puerto Vallarta,

Mexico, 243-248

Nichols, J., Shaffer, B., & Shockey, K. (2003). Changing

the face of instruction: Is online or in-class more

effective? College & Research Libraries, 64(5), 378-

388.

O’Neal, K., Jones, W. P., Miller, S. P., Campbell, P., &

Pierce, T. (2007). Comparing Web-based to traditional

instruction for teaching special education content.

Teacher Education and Special Education, 30(1), 34-

41.

Riel, M., & Harasim, L. (994). Research perspectives on

network learning. Machine-Mediated Learning, 4(2-3),

91-113.

Sweeney, J., O’Donoghue, T., & Whitehead, C. (2004).

Traditional face-to-face and web-based tutorials: A

study of university students’ perspectives on the roles

of tutorial participants. Teaching in Higher Education,

9(3), 311-323.

Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Self-efficacy for self-

regulated learning: A validation study. Educational

and Psychological Measurement, 68(3), 443-463.

Wilson, S. P., & Harris, A. (2002) Evaluation of the

Psychology Place: a Web-based instructional tool for

psychology courses. Teaching of Psychology, 29(2),

165-168

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-

regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 81, 329-339.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and

Academic achievement: An overview. Educational

Psychologist, 25(1), 3-17.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1994). Dimensions of academic self-

regulation: A conceptual framework for education. In

D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Self-

regulation of learning and performance: Issues and

educational applications (pp. 3-21). Hillside, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation

and motivation: Historical background,

methodological development, and future prospects.

American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166-

183.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1988). Construct

validation of a strategy model of student self-regulated

learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 284-

290.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

26