ON THE IMPROVEMENT OF MOTIVATION IN USING A

BLENDED LEARNING APPROACH

A Success Case

Diana Perez-Marin

1

and Ismael Pascual-Nieto

2

1

Computing Languages and Systems I Department, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Móstoles, Madrid, Spain

2

Computing Science Department, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Keywords: Motivation, Blended Learning, Assessment Methods, Technology Enhanced Learning.

Abstract: Blended Learning approaches combine face-to-face instruction with some type of computer-based

education. In this paper, the proposed combination is teaching in class and reviewing after class using an on-

line free-text scoring assessment system. In our first experiments with non Computer Science university

students, we asked their teachers to motivate them with the possibility of getting more training for the final

exam. However, only 5 students (11% of the class) reviewed with the computer after class on a regular

basis. Therefore, we studied and applied a set of principles to improve the motivation of using the Blended

Learning approach, and to get more students to review after class. After applying these principles 78% of

the non Computer Science university students reviewed with the computer on a regular basis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Blended Learning (BL) approaches combine face-to-

face instruction with some type of computer-based

education (Graham, 2005). In this way, it is possible

to combine the advantages of traditional face-to-face

instruction and computer-based education while

minimising the negative features of each (Klein et al.

2006).

Some advantages reported for traditional face-to-

face instruction are keeping the contact with the

teacher and thus, having immediate answers to

doubts and questions; and removing the isolation

feeling reported when using on-line education

(McElrath & McDowell, 2008).

Some advantages reported for computer-based

education are: temporal and spatial flexibility

because students can use the computer application

from any place and at any time; the possibility of

getting adaptive and personalised training; and,

allowing students to review at their own rhythm.

Furthermore, there are benefits inherent to the

use of BL approaches such as the ones reported by

Singh (2003) and Kim (2007): to reach more

students; to increase the learning efficiency; to

reduce costs; to improve the teaching methodology;

and, to have better logistics.

The literature on BL has focused on the

description of BL systems and methodologies.

However, up to our knowledge, little work has been

published assessing the relationship between

blended learning and motivation to learn.

In our previous experiments (Pérez-Marín et al.

2007), we have observed that Computer Science

Students are eager to use computer applications as a

complement to their traditional lessons.

However, non Computer Science students, albeit

not having technical difficulties in using computer

applications, are not so eager to use BL systems

without external motivation.

In this paper, several principles to improve the

motivation of non Computer Science students to use

the BL system to review after class are gathered. An

experiment in which these principles were used is

also described. We consider it a success case

because when the principles were applied the

percentage of students using the BL system was

increased from 11% up to 78%.

The organisation of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 briefly reviews the related work; Section 3

provides our proposed list of principles; Section 4

describes the experiment; and, finally Section 5 ends

with the main conclusions and lines of future work.

84

Perez-Marin D. and Pascual-Nieto I. (2010).

ON THE IMPROVEMENT OF MOTIVATION IN USING A BLENDED LEARNING APPROACH - A Success Case.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 84-89

DOI: 10.5220/0002775700840089

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 BRIEF REVIEW OF THE

LITERATURE IN MOTIVATION

Motivation in the educational field can be defined as

the attention and effort required to completing a

learning task (Moshinskie, 2001).

Motivation is a key factor for learning,

irrespectively of the nature of the learning process:

traditional learning, e-learning, b-learning, m-

learning, etc. (Wlodkowski, 1985; Dick & Carey,

1996; Hodges, 2004; Lynch & Dembo, 2004; Klein

et al. 2006; Keller, 2008).

According to Ryan & Deci (2000), two

important variables have to be distinguished in

relation to the motivation: the level of motivation

(i.e. how much motivation), and the type of

motivation (i.e. the orientation of the motivation).

The level of motivation is difficult to assess

given its subjective nature. Nevertheless, it is

possible to use questionnaires (Keller, 2008).

Regarding the type of motivation, at least three

different theories and two models can be

distinguished (Hodges, 2004), as it is reviewed in

the rest of this section.

The attribution theory holds that learners can

find controllable or uncontrollable reasons when

trying to explain their successes and failures. The

motivation stops when the reasons found are

uncontrollable. It is because students believe that

they are unable to perform the task.

Therefore, instructors should make an effort

to help learners to attribute the learning

outcomes to controllable reasons, and thus to

increase the motivation of the students.

The expectancy-value theory holds that students

expect certain results for their behaviour. The

motivation stops when the students stop thinking

that they are going to achieve the expected results.

Therefore, the bigger the likelihood perceived

by the students of getting the expected results is,

the bigger their motivation to work in the task is.

The goal theory holds that establishing goals is

the key to keep motivation in the time. In fact,

Beatty-Guenter (2001) identified goal orientation as

a significant attribute of those learners who

completed their distance course; and, Thompson

(1998) noted that learners who set clear goals

perform better.

Several types of goals can be distinguished. For

instance, proximal goals can be achieved in short

time, whereas distal goals are to be achieved in a

longer future. Furthermore, it should be explained

how to achieve the goals. The motivation stops when

there are not goals established, there are only distal

goals, or students do not know how to achieve the

established goals.

Therefore, several proximal goals regarded by

the students as feasible should be established

during the course.

It can be observed that these theories are quite

similar. In fact, they share some common underlying

concepts, such as the intrinsic/extrinsic nature of

motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to doing

something because it is inherently interesting or

enjoyable. Extrinsic motivation refers to doing

something because it leads to a separable outcome.

Student with intrinsic motivation can learn in any

situation, therefore the focus should be placed on

students who need extrinsic motivation.

Regarding the models, the Time Continuum

(TC) Model, proposed by Wlodkowski in 1985,

claims that the motivation is crucial in three critical

points of the learning process: at the beginning

(attitude and needs), at the middle (stimulation and

affect) and at the end (competence and

reinforcement).

The ARCS model, firstly proposed by Keller in

1987 and studied since then (Keller, 2008), claims

that 6 categories has to be reviewed.

The first four categories are the original that

gave the name to the model: Attention, Relevance,

Confidence and Satisfaction. The last two added

categories are: volition (Kuhl, 1987) and self-

regulation (Zimmerman, 1998).

3 SOME PRINCIPLES OF

MOTIVATION

3.1 Explanatory Notes

Students with intrinsic motivation usually do not

have difficulties in any learning situation. Therefore,

the principles gathered in this chapter are mainly

devised for students who need extrinsic motivation.

In order to make the reading of these principles

easier, they are presented ordered by its source,

according to the previous section. For instance,

principles related to the theories are presented before

than principles related to the models.

If the same principle is related to more than one

theory or model then it is just mentioned the first

time that it appears.

It is out of the scope of this paper to create a

complete list of principles for improving the

motivation, as the focus is on the relevant principles

to improve the motivation in Blended Learning

approaches.

ON THE IMPROVEMENT OF MOTIVATION IN USING A BLENDED LEARNING APPROACH - A Success Case

85

3.2 List of Principles

1. Learners should attribute the learning outcomes

to controllable reasons (attribution theory).

2. Students should believe that they will get the

expected results (expectancy-value theory).

3. Several proximal goals should be established

during the course (goal theory).

4. The needs of the students should be reviewed

before the course starts (TC model).

5. The goals of the course should be clearly stated

at the beginning (TC model, ARCS model).

6. The activities provided to the student should be

varied (TC model, ARCS model).

7. Immediate and adaptive feedback should be

provided during and at the end of the course (TC

model, ARCS model).

8. The curiosity of the students should be aroused

and sustained (ARCS model – attention).

9. The instruction should be perceived as relevant

to the personal values to the students or

instrumental to accomplish the expected goals

(ARCS model – relevance).

10. Students should have the personal conviction

that they will be able to succeed in mastering the

learning task (ARCS model – confidence).

11. Students should anticipate and experience

satisfying outcomes to a learning task (ARCS

model – satisfaction).

12. Students should be helped in applying volitional

(self-regulatory) strategies to protect their

intentions (new ARCS model – volition and self-

regulation).

4 EXPERIMENT

4.1 Settings

In the courses 2007/2008 and 2008/2009, 45

students of the English Studies degree were asked to

participate in an experience of using a Blended

Learning approach for their Pragmatic course

(Pérez-Marín et al. 2007).

The goal was to study the impact of using a

Blended Learning approach in a non-technical

domain with non Computer Science students. The

BL approach was as follows: students could keep

attending to their traditional lessons with their

teacher, while they would also have the possibility

of reviewing after class from any computer

connected to Internet at any time.

However, it was decided that the first session of

using the BL system would be in class. It is because

we wanted to check whether non Computer Science

students found any difficulty in using the system.

The mean age range of the students was 22 years

old with 1 year deviation, except for the 2007/2008

course in which one student was 45 years old.

The participation in both experiences was

voluntary. Students were initially motivated by their

teachers in class. The teachers told them that

although the use of the BL approach would not have

a percentage in the final score of the course, it would

help to solve difficult cases (e.g. students with a near

pass score who would pass the course).

After that initial motivation was told in the first

class of using the BL system, no more reinforcement

messages were given to follow the BL approach.

4.2 Application of the Principles

The list principles presented in Section 3.2 was used

as the starting point to choose which principles

could be applied for our BL approach.

The application of the principles for the

2007/2008 and 2008/2009 courses is shown in Table

1.

4.3 Results

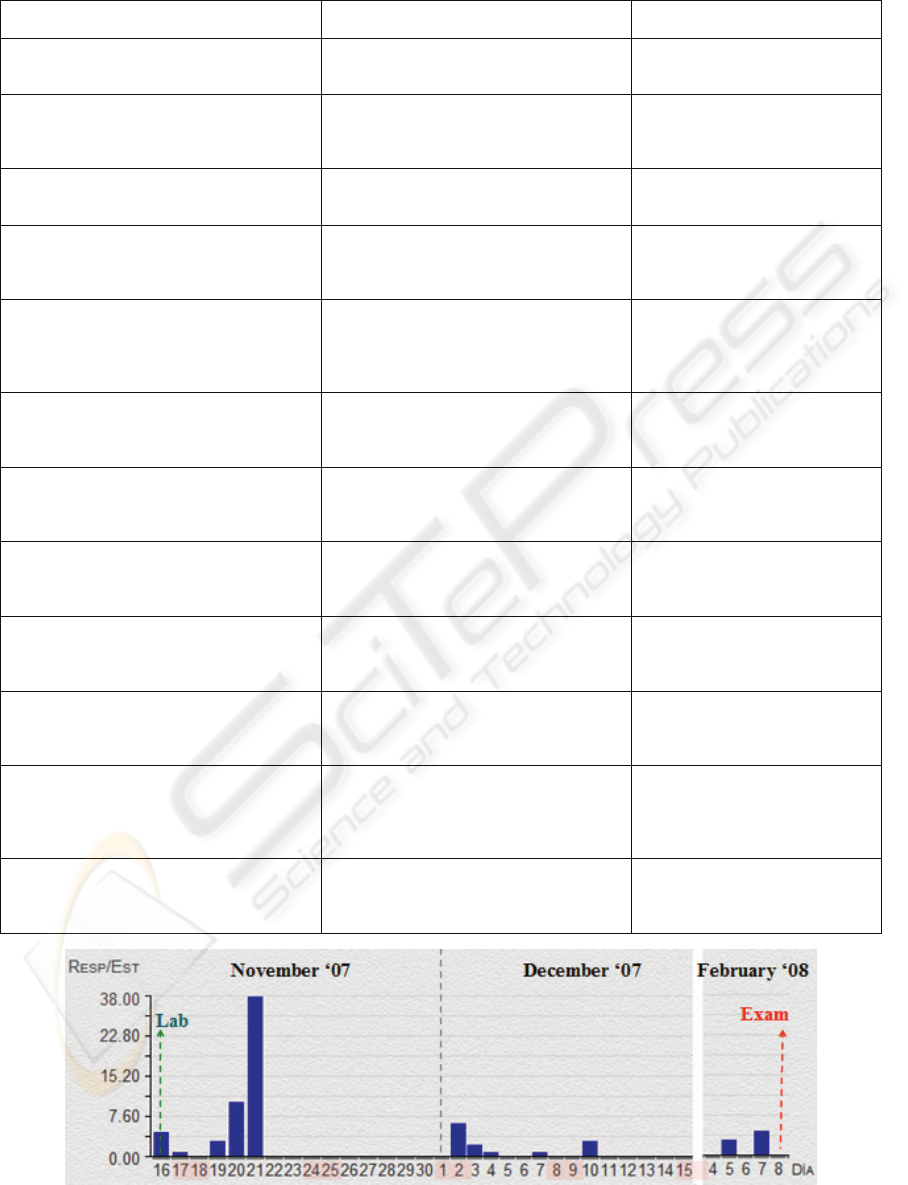

In the 2007/2008 course, 22 students (49% of the

total class) attended to the first session of using the

BL system in class. Figure 1 shows a histogram

representing the frequency of use of the BL system.

In the histogram, each bar represents the number

of questions answered each day. As can be seen,

after the first days in which the system was used up

to the point of answering 38 questions in one day,

the frequency of use decreases until stopping at all.

In general, only 5 students (11% of the class)

used regularly the BL system during the course to

review after class. The rest of the students claimed

that they had too much compulsory work to devote

time to voluntary activities.

Nevertheless, we thought that it could also be

due to the fact that more than half of the principles

gathered from the motivation in learning literature

were not applied (as shown in Table 1).

Furthermore, we wanted to test if the next year

we would obtain the same results. Therefore, we

asked the teachers of the course just to make the

necessary modifications to apply the rest of the

principles, except the last one that is kept as future

work (as shown in Table1).

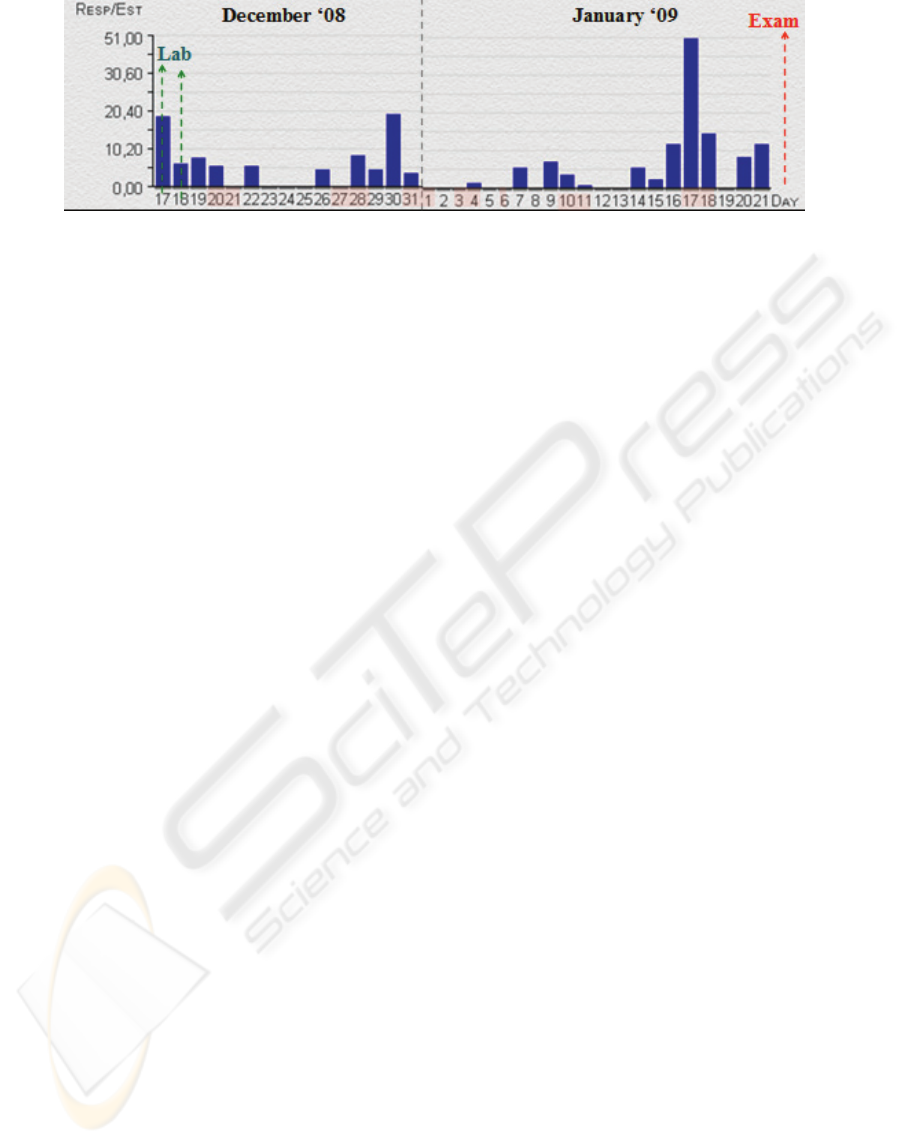

The use of the BL system changed as

represented in Figure 2. As can be seen, and

although still not all the students used the system

regularly, in the 2008/2009, 35 students (78% of the

class) used it on a more regular basis.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

86

Table 1: Application of motivation principles in the 2007/2008 and 2008/2009 BL experiments.

Principle

Application in 2007/2008 Application in 2008/2009

Learners should attribute the outcomes to

controllable reasons.

Students were told that using the BL system

to review is a matter of practise.

Same than 2007/2008

Students should believe that they will get the

expected results.

This principle was not applied.

Students were told that more

exercises would appear if they

keep using the BL system.

Several proximal goals should be established

during the course.

Students could follow their progress in the

BL system.

Same than 2007/2008

The needs of the students should be reviewed

before the course starts.

This principle was not applied. In fact, the

course was created without knowing the

students and their needs.

The teachers of the students who

knew their needs and the lessons

created the course.

The goals of the course should be clearly

stated at the beginning.

Students were told that in order to consider

that they have passed the course in the BL

system, at least half of the questions have to

be answered.

Same than 2007/2008

The activities provided to the student should

be varied.

This principle was not applied. In fact, many

of the questions ask for a definition of a

concept.

Although the BL system keeps

asking only questions, their type

changed (comparison,...)

Immediate and adaptive feedback should be

provided in the course.

A model of each student is kept, so that for

each question, immediate and adaptive

feedback can be provided.

Same than 2007/2008

The curiosity of the students should be

aroused and sustained.

This principle was not applied.

Each two weeks new questions

were introduced into the course to

keep the students’ attention.

The instruction should be perceived as

relevant and useful.

This principle was not applied.

Given that their teachers have

created the course, it was more

related to the lessons in class.

Students should have the conviction that they

will be able to succeed.

This principle was not applied.

In the first session in class, we

assured that all students felt that

they could use the system.

Students should anticipate and experience

satisfying outcomes.

Students could observe how they progressed

in the course in relation to the rest of their

colleagues.

As well as the feedback that

students could see, their teachers

answered more mails and followed

their evolution.

Students should be helped in applying

volitional strategies.

This principle was not applied.

This principle was not applied.

Figure 1: Frequency of use of the BL system during the 2007/2008 course.

ON THE IMPROVEMENT OF MOTIVATION IN USING A BLENDED LEARNING APPROACH - A Success Case

87

Figure 2: Frequency of use of the BL system during the 2008/2009 course.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Blended Learning combines the traditional face-to-

face instruction with computer-based education. In

this way, it combines the advantages of both

instructional methods, while minimising their

disadvantages.

Many BL experiments have been performed by

Computer Science teachers to Computer Science

students. Those students are usually eager to use

computer applications.

On the other hand, non Computer Science

students may feel disoriented without knowing how

to organise their time to study or how to navigate in

the system. Thus, they may stop using the BL

system altogether.

Motivation is a key factor for learning in general,

and for computer-based education is particularly

relevant.

Several types of motivation can be distinguished.

For instance, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

should be differentiated. Ideally, all students could

be intrinsically motivated. It would help them to take

full advantage of any learning situation.

However, it is not usually the case. Therefore,

principles should be applied to provide extrinsic

motivation to students.

The review of the literature of motivation in

learning provides several theories and models, from

which 12 principles can be gathered.

In particular, it was our hypothesis that by

applying these principles, there would be an

improvement in using a BL approach in which

students attend to traditional lessons to learn, and

use the BL system to review after class.

An experiment performed during the 2007/2008

and 2008/2009 courses with English Studies

university students has provided evidence to support

that hypothesis.

While in 2007/2008, from the 45 students

enrolled in the course, only 5 students (11% of the

class) regularly used the BL system when it was

offered as voluntary. In the 2008/2009, 35 students

(78% of the class) regularly used the BL system also

being a voluntary activity.

It is our belief that the improvement of the

motivation was due to the application of the

principles. In fact, while in the first year, only 5

principles were applied, in the second year 11

principles (more than the double) were applied.

In particular, the 5 principles applied in

2007/2008 were: learners should attribute the

outcomes to controllable reasons, several proximal

goals should be established during the course, the

goals of the course should be clearly stated at the

beginning, immediate and adaptive feedback should

be provided in the course, and students should

anticipate and experience satisfying outcomes.

The new 6 principles applied in 2008/2009 were:

students should believe that they will get the

expected results, the needs of the students should be

reviewed before the course starts, the activities

provided to the student should be varied, the

curiosity of the students should be aroused and

sustained, the instruction should be perceived as

relevant and useful, students should have the

conviction that they will be able to succeed, and the

principle indicating that students should anticipate

and experience satisfying outcomes was improved.

It has been particularly relevant the introduction

of the ARCS model with the principles of the

2008/2009 year. For instance, the progressive

introduction of the course in the BL system to keep

the attention of the students, and the increase of the

relevance feeling as the course was more related to

the lessons in class.

As future work, we plan to also apply the last

principle (Students should be helped in applying

volitional strategies) to incorporate the volition and

self-regulatory categories of motivation.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

88

A possible strategy to incorporate that principle

and keep improving the motivation of using the BL

system could be the use of an animated pedagogical

conversational agent (Keller, 2008).

The agent could be a student companion in the

computer application. Students could ask for their

help when they have some doubt, and/or the agent

could also recommend some actions to the students

when they seem disoriented, or it has been detected

that they are having difficulties in completing some

tasks in the system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been sponsored by Spanish Ministry

of Science and Technology, project TIN2007-64718.

REFERENCES

Beatty-Guenter, P. 2001. Distance education: does access

override success? Paper presented Canadian

Institutional Research and Planning Association 2001

conference. Victoria, British Columbia.

Dick, W., Carey, L., 1996. The systematic design of

instruction (4th ed.). New York: Longman.

Graham, C.R., 2005. Blended Learning Systems:

Definition, Current Trends, and Future Directions,

Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives,

local designs, Pfeiffer Publishing, 3-21.

Hodges, C.B., 2004. Designing to Motivate: Motivational

Techniques to Incorporate in E-Learning Experiences.

The Journal of Interactive Online Learning 2(3).

Keller, J., 2008. First principles of motivation to learn and

e

3

-learning. Distance Education journal, Academic

Research Library, 29(2), 175-185.

Keller, J. M., 1987. Development and use of the ARCS

model of instructional design. Journal of Instructional

Development, 10(3), 2-10.

Kim, W., 2007. Towards a Definition and Methodology

for Blended Learning, Blended Learning, Prentice

Hall, Pearson Education, 1-8.

Klein, H., Noe R., Wang, C., 2006. Motivation to learn

and course outcomes: the impact of delivery mode,

learning goal orientation, and perceived barriers and

enablers. Personnel Psychology journal, 59, 665-702.

Kuhl, J., 1987. Action control: the maintenance of

motivational states. In F. Holisch & J. Kuhl (Eds.)

Motivation, intention and volition, Springer, 279-291.

Lynch, R., Dembo, M., 2004. The Relationship between

Self-Regulation and Online Learning in a Blended

Learning Context. International Review of Research

in Open and Distance Learning, 5 (2).

McElrath, E., McDowell, K., 2008. Pedagogical strategies

for building community in graduate level distance

education courses, Journal of Online Learning and

Teaching 4(1).

Moshinskie, J., 2001. How to keep e-learners from e-

scaping. Performance Improvement, 40(6), 28-35.

Pérez-Marín, D., Pascual Nieto, I., Alfonseca, E.,

Anguiano, E., Rodríguez, P., 2007. A study on the

impact of the use of an automatic and adaptive free-

text assessment system during a university course,

Blended Learning, Pearson, Prentice Hall, 186-195.

Ryan, R.M., Deci, E.L., 2000. Intrinsic and Extrinsic

Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions.

Contemporary Educational Psychology 25, 54–67.

Singh, H., 2003. Building effective blended learning

programs, Educational Technology Magazine,

Educational Technology Publications, 43(6), 51-54.

Thompson, M. M., 1998. Distance learners in higher

education. In C. C. Gibson (Ed.) Distance Learners in

Higher Education: Institutional responses for quality

outcomes, Madison, WI.: Atwood Publishing, 9-24.

Wlodkowski, R.J., 1985. Enhancing adult motivation to

learn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Zimmerman, B.J., 1998. Academic studying and the

development of personal skill: a self-regulatory

perspective. Educational Psychologist, 33 (2/3), 73-

86.

ON THE IMPROVEMENT OF MOTIVATION IN USING A BLENDED LEARNING APPROACH - A Success Case

89