THE NEED FOR SPECIAL GAMES

FOR GAMERS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Andrea Hofmann, Imke Hoppe and Klaus P. Jantke

Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology IDMT, Children’s Media 99084 Erfurt, Germany

Keywords: Serious games, Intellectual disabilities, Observatory research, Requirement specification, Game design.

Abstract: People with intellectual disabilities are a part of our society, but unfortunately, they are often excluded.

Their assistance includes everything they need in their lives. The work in the various workshops for people

with disabilities often gives them the feeling that they are needed, but few can find access to an independent

life by further developing and training of themselves. The pleasure of (digital) game playing and learning

with a game is not yet considered a standard constituent of leisure time activities in sheltered workshops for

people with an intellectual disability. Qualitative studies with off-the-shelf digital games have demonstrated

enormous potentials of game playing for the assistance of people with an intellectual disability. However,

conventional off-the-shelf digital games have severe limitations. The authors’ qualitative studies lead (i) to a

requirement specification and (ii) to the design and implementation of a completely new digital game

meeting essential needs of people with an intellectual disability. The present publication surveys the results

of the qualitative observations and leads to the recently completed game design.

1 INTRODUCTION

The authors’ main motivation is to contribute to the

quality of the life of people with intellectual

disabilities, who work regularly in sheltered

workshops.

An intellectual disability is impaired if cognitive

and partially physical abilities are permanently

limited and when help is needed to participate in

everyday life and work. The intellectual disability

and the intended help by others should not lead into

negative consequences concerning the personality,

family and the attendance in public life (World

Health Organization, 2001), (Bundesregierung,

2004), (Cloerkes, 1988).

Contributions to the peoples’ life quality may

become part of a systematic assistance. The present

work focuses on the usage of digital games.

Which role do digital games play in the current

assistance of people with an intellectual disability, in

general, and in their supervised leisure time, in

particular? In case game playing is not just fun,

which other effects (maybe educational, e.g.) may be

observed? What about the potentials of off-the-shelf

commercial games? Do we need ad hoc game

designs and implementations?

Beyond the contribution to those peoples’

quality of life, the authors are focussing training and

learning. It is the authors’ strong belief that people

with an intellectual disability do need more support

in daily life, in particularly in playful learning and

training.

The authors want to clarify that the issue of

accessibility is certainly one of the main require-

ments of the special education. In the case of games,

the following study indicated that there are some

special needs which can be supported individually

and personalized by ‘special games’. Technology-

enhanced approaches are probably quite promising,

but seem to be much underrepresented in the

scientific discourse, in general, and on leading

conferences such as CSEDU, in particular, at least

for adults with intellectual disabilities.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

An enormous number of authors have investigated

the challenge of getting computer systems engaged

for educational purposes including the special needs

of persons with an intellectual disability. An

overwhelming majority of publications ranging from

(Gresham and Elliott, 1987) to (McCray, Vaughn

220

Hofmann A., Hoppe I. and Jantke K. (2010).

THE NEED FOR SPECIAL GAMES FOR GAMERS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 220-225

DOI: 10.5220/0002781102200225

Copyright

c

SciTePress

and Neal, 2001), (Sullivan, Lautz and Zirkel, 2000),

(Deeney, Wolf and O’Rourke, 2001), (Weiss and

Lloyd, 2003), (Frederickson and Turner, 2003),

(Fuchs and Fuchs, 2005), and (Graham and Harris,

2005), are focusing children and school problems. In

contrast, the present approach is addressing the

needs of adults.

Furthermore it is stated as an important target of

special education to support the computer literacy,

because the use of computers became central in

everyday life and the employment market

(Sonderschul-net.de, 1997). Usability and regular

feedbacks were stated as main requirements of

software programs for people with special needs. In

a majority of publications such as (Cosden et al.,

1987), (MacArthur et al., 1986), (Rieth et al., 1988),

authors have complemented the potentials by

varying hints to the limitations of information and

communication technologies.

It is only natural that a larger number of authors’

response is the dedicated ad hoc development of

special purpose approaches as surveyed in (Riva,

1997). There is the particularly important aspect that

“any educational innovation is filtered through

teachers as they modify instructional activities to fit

their beliefs and the instructional and management

routines in their classrooms” (MacArthur and

Malouf, 1991).

Corresponding to the results of the literature

review on the game market we mainly found games

for children with intellectual and physical dis-

abilities. Most recent games offer a training of single

cognitive skills and tasks, like counting. Some

representatives for the development of specific

hardware and software for children with disabilities

are “World of Genesis” (Genesis, 2008), “LifeTool”

(Clevy, 2008), “Läramera” (LäraMera Program AB,

2009) and “Inclusive Technology” (Inclusive

Technology, 2008). The dedicated hardware can be

used by adults, while the software has been

developed almost exclusively for children with

disabilities.

The conducted study deals with the question

which learning effect can be achieved by people

with intellectual disabilities while playing

educational games. In addition to this question it

should be clarified to what extent playing and

learning can be useful to this target group.

3 METHOD

As empirical method we choose a case study,

because we wanted to analyse how digital games

could be integrated into the daily life of the sheltered

workshops and how they affect the people working

there.

So the study was conducted in a sheltered

workshop (Germany/Thuringia) for adults with

intellectual disabilities who have completed their

compulsory education. The workshop is divided into

different areas, including the five workspaces wood,

metal, installation, kitchen and vocational training.

The study used a mixed-method-design and

integrates qualitative as well as quantitative

methods. The quantitative approach was needed to

answer certain predefined research questions and to

follow the duration of the analysed game, which

consists of 28 game units. The qualitative approach

was used to clarify the key dimensions of how

learning was enhanced by digital games and to reach

an in-depth understanding of these processes.

Therefore a longitudinal participant observation

(10/2008-01/2009) was chosen as main research

instrument. Within the observation a protocol was

used which integrated open plus well-structured

criteria to realise the qualitative and the quantitative

approaches. The structured, quantitative elements in

the protocol used scales ranging from 1 to 5 (Likert-

Scale).

Because in Germany there are no digital games

for adults with intellectual disabilities available, we

used the preschool games “Janosch – meine große

Vorschulbox”, “Lauras Vorschule” and “Die Mini-

Mäuse” as test objects. With these serious games the

main research questions could be analysed, because

they provide the requirements the supervisors of the

sheltered workshop defined and reach the target

group.

The sampling is characterised by the qualitative

approach taking very different people and their

varying computer literacy into account. The chosen

persons A (Age 40, female), B (Age 28, female) and

D (Age 25, female) have only a slight computer

literacy. Person C (Age 21, male) has basic

knowledge about using the computer.

These games were played over a period of 14

weeks with 2 game units per week, each lasting 45

Minutes. The structure of the participant observation

was to set up a scenario in which the participants

were asked to play the game while the observer sits

aside.

The results of the empirical study will be

outlined as requirements in chapter 4 and should

serve as guidelines for designing and programming a

digital learning game (see chapter 5).

THE NEED FOR SPECIAL GAMES FOR GAMERS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

221

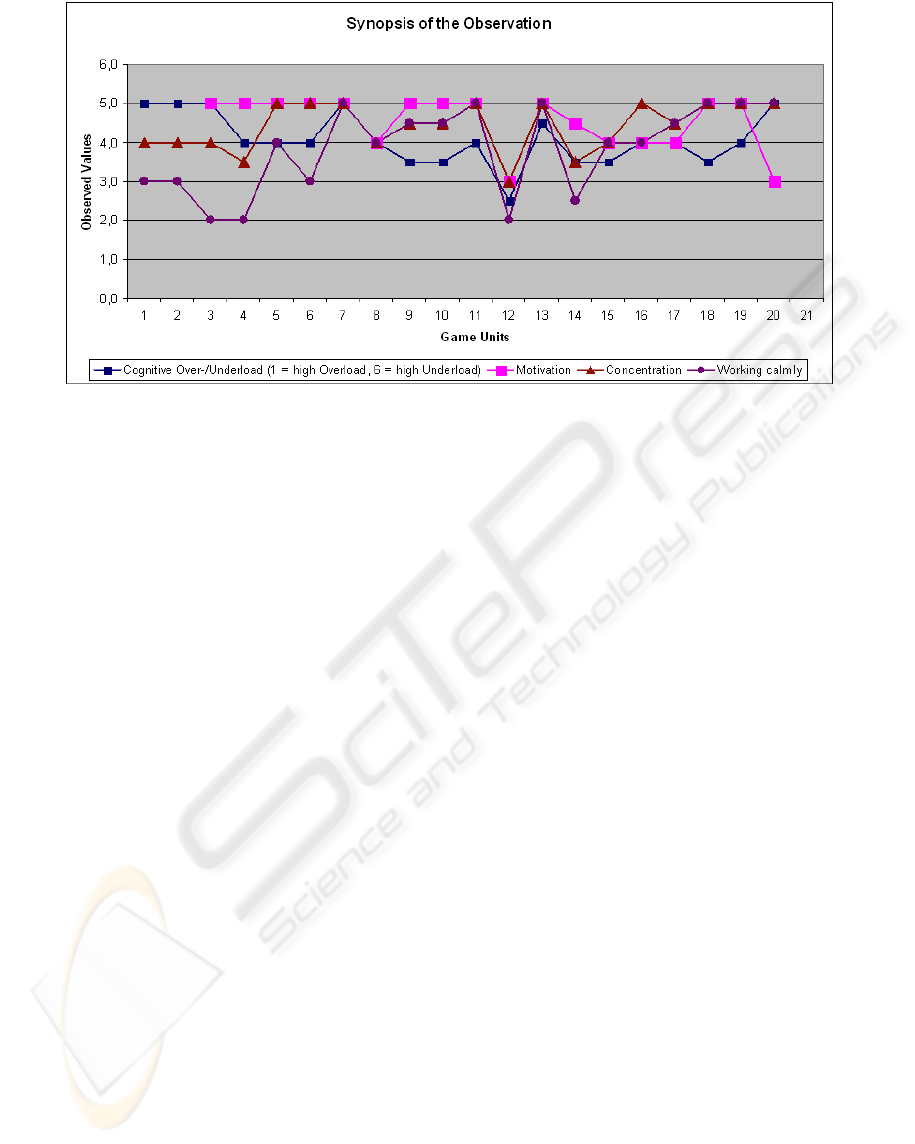

Figure 1: Selected results of participant C concerning the quantitative part of the observation.

4 RESULTS

The results showed both positive effects on learning

and negative aspects of game usage.

The main positive effects on the learning

process are characterised by improvements

concerning the computer literacy, for example

handling the input devices. The observation

protocols indicated increasing concentration,

perseverance and patience as well as an

improvement in working very calmly and precisely

concerning playing the game and solving the tasks.

Figure 1 shows a clear correlation between an

adequate difficulty and a high motivation (game

units 9-10).

An increase of competences and knowledge

regarding the daily-life topics was ascertained, e.g.

nutrition, traffic rules, and dealing with money.

Regarding the motor skills while handling the

computer we found an improvement in the ability to

react, the eye-hand-coordination and the orientation

in virtual rooms.

Also some negative aspects of game usage were

analysed. The learning topics within the chosen

games do not concern aspects of the reality of the

participants. All tested games communicate the

instructions and explanations either through an

acoustic or a written mode, which was problematic

for those, who are not able to read.

As mentioned earlier the concentration decreases

if the game levels are either too easy or too

complicated (see figure 1, e.g. game units 11-13). In

the tested games there were only a few possibilities

to modify the navigation tools. Only one game

offered the option of printing out a certificate about

the achieved score, a detail which was very much

appreciated by all participants of the study.

Because of the fixed order of the given answers,

the participants recognised response patterns, which

were often experienced as negative.

Summarising, the results of the study show a

strong interest and motivation in playing digital

games across all participants, e.g. participant B said:

“That’s why I’m here: to learn something, finally!”

(“Dafür bin ich ja da, um was zu lernen, endlich!”);

participant D claimed: „Please, remember me that

we train calculation next week!” (“Erinner’ mich

nächste Woche daran, dass wir Rechnen üben!“).

Moreover, they affirmed that playing digital

games challenged them in a positive manner and

varied their daily life routines within the sheltered

workshop. During the study this interest decreased a

little, especially when the participants felt

unchallenged by the game. Participant C showed this

significantly: “Today, I have no passion to play this

game, it is always the same.” (“Darauf habe ich

heute keine Lust, das ist ja immer wieder das

Gleiche”). This perceived cognitive underload

differed from person to person, depending on their

knowledge, motivation and computer skills. As a

main intervening variable on learning processes the

ever-changing disposition and concentration were

analysed. One of the most striking results is the huge

interest in computer-related knowledge, e.g. to get to

know how a computer works. However, only a few

changes in the social behaviour of the participants

have been observed, e.g. one participant became

more outgoing, as the supervisors told us.

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

222

Even more, the supervisors reported that the

game showed the participant’s skills more detailed

than they expected.

5 REQUIREMENT ANALYSIS

Based on these empirical results a requirement

analysis was outlined. The requirement analysis

provides a first step to encourage the development of

„special games“ for adults. The main concept to

realise the requirements through a digital game is

adaptivity, which affects several requirements.

5.1 Basic Framework Requirements

One of the major requirements is drawn from the

literature (see chapter 2) and claims to stage the

game closely to the reality of the players, e.g.

using symbols (words, pictures) which are well

understandable and commonly known. The content

should display the every-day life of the participants

so that the lessons learned during the game can be

easily transferred and put into practice. Therefore

the game designers should clarify beforehand which

learning areas should be enhanced. We suggest

using mini-games with single delimitable steps to

avoid a cognitive overload and to allow individual

interruptions without loosing the game. Regarding

the instructions we argue for using all possible

perceptional modes (oral, written,...) at the same

time, so that the user (or their supervisors) can

choose how the instructions should be

communicated. Thereby a wide range of intellectual

disabilities are taken into account. The possibility of

an individual key assignment is considered as very

helpful. Furthermore the possibility of choosing and

combining different input devices, like the mouse

and keyboard, should be given. This demand is

caused in disabilities, which do not allow writing or

reading. Since some users are not able to insert a

CD-ROM into the drive due to their limited physical

abilities, the game should be playable without a

CD-ROM or other additional preparations. In

general it should be possible to play the game

autonomously so that the need of permanent

assistance can be avoided. Hence an excellent and

invisible help function is needed. It should be

prevented to give monotone answers and feedback

patterns, because this seems to be exhausting,

especially for people with intellectual disabilities. A

simple graphic design with high-contrast colours

will encourage the visual perception and support the

orientation within the game. The menu’s structure

should be as simple as possible, so that the main

functionalities like saving the game are easy to find.

The menu should also integrate a button to print

documents, like the certificate with the reached high

score. For supervisors as well as for parents it is

helpful to have a game protocol, which should be as

well available though the menu.

5.2 Didactical Requirements

One of the major didactical principles is to support

and to challenge the learner individually. So there

is a need for a well-adjusted balance (Mortimore,

1999). Thereby a cognitive overload as well as a

cognitive underload should be avoided. To impede

an overload of the participants, e.g. the possibility to

repeat tasks and levels is needed. To impede

underload new stimuli can be given through regular

updates of certain tasks, levels or mini-games.

Additionally a motivating, friendly and varying

feedback will create a supporting learning

environment. For the supervisors it would be a

benefit to be able to assess the skills and knowledge

of new participants by the digital game.

It would be an engaging tool to create a

competitive atmosphere for those players, who seek

for some challenges. This can be reached by offering

a game level with a high score.

5.3 Adaptivity as Main Requirement

Adaptivity is a key feature of modern information

and communication systems offering added value to

literally all users or customers through the system’s

ability to adapt to individual needs and desires.

A certain system’s adaptivity, naturally, requires

the system “to know” something about the user for

being able to offer varying services to different users

(Popescu et al., 2007). Therefore, adaptivity requires

user modelling, a key issue not to be discussed here

in more depth.

To many people, adaptivity is a nice feature that

makes products and services more attractive and,

perhaps, more useful. To producers and service

providers, adaptivity is a nice feature that helps to

gain advantage over competitors.

To people with intellectual disabilities, the

adaptivity of the given system is not only nice to

have, but a feature of decisive relevance. The

authors’ results (see section 4.2 above) exhibit that

people with intellectual disabilities are not very

much tolerant to deviations from their needs and

requirements. If a system such as a game does not

closely enough fit their individual needs, it is very

THE NEED FOR SPECIAL GAMES FOR GAMERS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

223

likely to fail in general.

Research into the adaptivity of digital games is a

current field of endeavours. Although there are

recent results of great interest (Charles et al., 2005),

(Torrente et al., 2008), these recent research

activities do not take into account the special needs

of people with intellectual disabilities.

Further work will have to weight the

requirements and to structure them regarding the

production process.

6 PROTOTYPING & OUTLOOK

Based on the requirements mentioned above the

authors are in the process of developing a game as

prototype for people with intellectual disabilities.

The prototype implements the most of the

requirements displayed in chapter 5.

To develop a realistic game environment, we

basically created a virtual copy of the sheltered

workshop, in which the study was conducted. The

images below show the main corridor of that

institution.

Figure 2: The virtual and the real sheltered workshop.

But because the game should not be exclusively

created for one single workshop, we decided to

design a holistic framework, in which different

ground plans of different sheltered workshops can be

depicted and staged as basic virtual game

environment (see figure 3).

As a side effect the content of the game as well

as the learning tasks are very comparable to the real-

life sheltered workshop so that possibilities of

knowledge transfer are given. It is even conceivable

that this has a positive impact on the individual

working performance.

Another learning objective is the expansion of

existing knowledge, as well as daily life oriented

skills, such as learning to read the clock and to use

money. Apart from this learning effect, people with

intellectual disabilities can hereby be encouraged

playfully to reach a more independent lifestyle.

The creation of a system that imparts learning

content playfully is one of the central objectives of

designing a computer game for people with

intellectual disabilities.

As an additional side effect, the target group is

engaged to use the computer as a learning medium

and instrument even for other contexts than games.

An anxiety-free use of new technologies on the one

hand and with the computer in particular is striven

here. Computer competences improve the chances to

be integrated into the employment market.

Figure 3: Ground plan of the virtual workshop.

The game will also provide the training of

various skills, such as the responsiveness,

concentration, endurance and patience. At least the

game should be funny and motivating.

For those reasons we chose mini-games,

especially to train certain skills selectively and for

doing this in an entertaining way. At the present

moment four mini-games are directly available

through the game environment and already

implemented. They train the visual perception,

orientation in rooms, handling of input devices,

counting, spelling and reading the time.

A main focus of the prototype is to implement

the adaptivity. This will be realised by an

incorporating user model. Within this user model all

relevant data about the individual users will be

stored. Because of this information the system

knows to what extent help and assistance are needed.

After finishing the prototype an evaluation will

be conducted. Using a similar research setting in the

same institution will make the results of the other

tested games comparable with the results of the

prototype. Moreover, we can analyse whether

positive learning effects and an entertaining

experience will occur and if these learning effects

are transferable to the daily-life reality of the

participants. The empirical research should as well

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

224

extend the evidence base concerning the usability in

general and especially in navigation. The results of

the empirical study will influence the redesign of the

prototype.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The present research and development has been

partially supported by the Thuringian Ministry for

Culture (TKM) within the project iCycle under

contract PE-004-2-1.

REFERENCES

Bundesregierung (2004). Sozialgesetzbuch. Rehabilitation

und Teilhabe behinderter Menschen.

Charles, D., Kerr, A., McAlister, M., McNeill, M.,

Kücklich, J., & Black, M. M., et al. (2005). Player-

Centred Games Design: Player Modelling and

Adaptive Digital Games. In Digital Games Research

Conference 2005, Changing Views: Worlds in Play,

June 16-20, 2005, Vancouver, British Columbia,

Canada .

Cosden, M. A., Gerber, M. M. and Semmel, D. S. (1987).

Microcomputer use within micro-educational

environments. Exceptional Children, 53:399–409.

Clevy (2008). Großtastatur. http://www.computer-fuer-

behinderte.de/produkte/2tast-grosstastatur.htm

Cloerkes, G. (1988). Behinderung in der Gesellschaft:

Ökologische Aspekte und Integration. In U. Koch

(Ed.), Handbuch der Rehabilitationspsychologie, 86–

100. Berlin: Springer.

Deeney, T.,Wolf, M., and O’Rourke, A. G. (2001). “I like

to take my own sweet time”: Case study of a child with

naming-speed deficits and reading disabilities. The

Journal of Special Education, 36(3):145–155.

Frederickson, N. and Turner, J. (2003). Utilizing the

classroom peer group to address children’s social

needs: An evaluation of the circle of friends

intervention approach. The Journal of Special

Education, 36(4):234– 245.

Fuchs, D. and Fuchs, L. S. (2005). Peer-assisted learning

strategies: Promoting word recognition, fluency, and

reading comprehension in young children. The Journal

of Special Education, 39(1):34–44.

Genesis (2008). Was steckt hinter Genesis? from

http://www.efi.fh-nuernberg.de/genesis/index.php?op

tion=com_content&view=article&id=45&Itemid=2.

Graham, S. and Harris, K. R. (2005). Improving the

writing performance of young struggling writers:

Theoretical and programmatic research from the

center on accelerating student learning. The Journal

of Special Education, 39(1):19–33.

Gresham, F. M. and Elliott, S. N. (1987). The Relationship

between Adaptive Behavior and Social Skills: Issues in

Definition and Assessment. The Journal of Special

Education, 21(1), 167-181.

Inclusive Technology (2008). Coping with Chaos, http://

www.inclusive.co.uk/catalogue/acatalog/coping_with_ch

aos.html

LäraMera Program AB (2009). Educational software for

children in pre-school age and up. http://

www.laramera.se/indexEng.htm

MacArthur, C. A. and Malouf David B. (1991). Teachers‘

Beliefs, Plans, and Decisions About Computer-based

Instruction. The Journal of Special Education, 25(5),

44-72.

MacArthur, C. A., Haynes, J. A., & Malouf, D. (1986).

Learning disabled students' engaged time and

classroom interaction: The impact of computer

assisted instruction. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 2, 189-198.

McCray, A. D., Vaughn, S., and Neal, L. V. I. (2001). Not

all students learn to read by third grade: Middle

school students speak out about their reading

disabilities. The Journal of Special Education,

36(1):17–30.

Mortimore, P. (1999). Understanding pedagogy and its

impact on learning. London: Chapman.

Popescu, E., Trigano, P., and Badica, C. (2007). Adaptive

Educational Hypermedia Systems: A Focus on

Learning Styles. In EUROCON: The International

Conference on “Computer as a Tool"‘: Warsaw,

September 9-12, 2473–2478. Warsaw.

Rieth, H. J., Bahr, C. M., Okolo, C. M., Polsgrove, L., and

Eckert, R. (1988). An analysis of the impact of

microcomputers on the secondary special education

classroom ecology. Journal of Educational Computing

Research, 4:425–442.

Riva, G. and Melis, L. (1997). Virtual reality for the

treatment of body image disturbances. In Riva, G.,

editor, Virtual Reality in Neuro-Psycho-Physiology.

Amsterdam: ios Press.

Sonderschul-net.de (1997): Zum Einsatz des Computers in

der Schule für Geistigbehinderte (Sonderschule) mit

dem Schwerpunkt: Erstellung von

Übungsprogrammen mit Autorensystemen

einschließlich eines praktischen Beispiels, http://www.

foerderschwerpunkt.de/download/examen/ComputerSf

G.pdf.

Sullivan, K. A., Lantz, P. J., and Zirkel, P. A. (2000).

Leveling the playing field or leveling the players?:

Section 504, the americans with disabilities act, and

interscholastic sports. The Journal of Special

Education, 33(4):114–126.

Torrente, J., Moreno-Ger, P., and Fernandez-Manjon, B.

(2008). Learning Models for the Integration of

Adaptive Educational Games in Virtual Learning

Environments. In Edutainment, LNCS 5093, 463–474.

Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Weiss, M. P. and Lloyd, J. W. (2003). Congruence

between roles and actions of secondary special

educators in cotaught and special education settings.

The Journal of Special Education, 36(4):58–68.

World Health Organization (2001). International

Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health,

http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

THE NEED FOR SPECIAL GAMES FOR GAMERS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

225