WEB SITE BRAND ATTRIBUTES AND E-SHOPPER LOYALTY

A Comparative Study of Spain and Scotland

Sandra Loureiro and Silvina Santana

Department of Economy, Management, and Industrial Engineering

Aveiro University, Campus of Santiago, Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Web site brand, Online shopping, B2C, Brand relationship, Brand image, Brand personality, Brand

association, Loyalty, PLS.

Abstract: This study examines the impact of web site brand personality, web site brand association, web site brand

image, and web site brand relationship on e-shopper loyalty to the web site. The model was estimated on

data from consumers of online products in Spain and Scotland using PLS technique. The findings suggest

that web site brand association and web site brand personality are good predictors of web site brand image.

However, web site brand image does not explain the intention of Spanish students to recommend a web site

and to use it to by again.

1 INTRODUCTION

Brands are important sources of competitive

advantage. Therefore, knowing how actual and

potential clients perceive a brand is fundamental

information for its management. In brand theory, a

brand is said to have attributes such as brand

personality, brand association, and brand image to

which brand knowledge is always linked (e.g.,

(Aaker, 1991; Keller, 1993, 1998)). Some authors

defend that consumer-brand relationship depends

largely on the successful establishment of brand

knowledge (Keller, 2003).

Brand knowledge can be formed directly from a

consumer’s experience. Therefore, brand attributes

might be crucial mediators between brand

experience and consumer-brand relationship. If such

a relation proves, understanding the way these

concepts interrelate with each other might be

valuable to inform marketing strategy formulation,

namely, in what concerns brand management.

The main objective of this work is to study the

direct impact of web site brand relationship and web

site brand image on loyalty. In addiction, we also

study the direct effect of web site brand association

and web site brand personality on web site brand

image. The model was estimated on data from 195

consumers of online products from two countries,

Scotland and Spain, using PLS technique.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

time that web site brand knowledge, mediated by

attributes like web site brand association,

personality, image, and relationship, is addressed in

such a way and the study differs from previous work

which has related brand knowledge of goods and

services (Bart, Shankar, Sultan, & Urban, 2005;

Chang & Chieng, 2006), sold through virtual stores

(web site) or physical stores. Secondly, this study

focuses on consumers’ experiences in two European

countries with very different levels of Internet use

for shopping.

Given the paucity of cross-country studies in this

area, using PLS (Partial Least Squares) might prove

to be valuable to considerably advance existing

knowledge and enhance current practices of web use

for retailing.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Constructs Definition

Brand image is defined here as perceptions about a

brand as reflected by the brand associations held in

consumer memory (Keller, 1993).

Brand personality is defined as the set of human

characteristics associated with a brand (Aaker,

1997). It is a comprehensive concept, which includes

257

Loureiro S. and Santana S.

WEB SITE BRAND ATTRIBUTES AND E-SHOPPER LOYALTY - A Comparative Study of Spain and Scotland.

DOI: 10.5220/0002783302570262

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technology (WEBIST 2010), page

ISBN: 978-989-674-025-2

Copyright

c

2010 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

all the tangible and intangible traits of a brand, such

as beliefs, values, prejudices, features, interests, and

heritage. A brand personality makes it unique. Brand

personality is seen as a valuable factor in increasing

brand engagement and brand attachment, in much

the same way as people relate and bind to other

people. Researchers have proposed that brand

personality is an aspect of brand image (Keller,

1993, 1998; Plummer, 2000) and results from

empirical studies indicate that brand personality

have a statistically significant positive influence on

brand image (O'Cass & Lim, 2001).

According to previous studies (Chang & Chieng,

2006; Keller, 1998), brand association is defined as

the information linked to the node in memory. This

information reflects an association between a range

of aspects and the brand in the mind of the

consumer. Brand associations have been presented

as critical components in developing a brand image

(Keller, 1993) and empirical studies have shown that

brands associations lead to the formation of a

distinct brand image in the minds of consumers

(Hsieh, 2002).

In this study brand relationship is defined as the tie

between a person and a brand that is voluntary or is

enforced interdependently between the person and

the brand (Chang & Chieng, 2006). A relationship

between the brand and the consumer results from the

accumulation of consumption experience.

Finally, loyalty is the intention to recommend a

product to other people and to buy it again

(Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996).

In this work, the above concepts are transposed

to the context of web site brand. We postulate that

web site brand personality, web site brand

association, web site brand image, and web site

brand relationship all hold different information that

link to web site brand, as happens with other

products (Aaker, 1991). Furthermore, we defend that

brand personality, brand association, brand image,

and brand relationship are antecedents of loyalty to a

web site brand (Chang & Chieng, 2006; O'Cass &

Lim, 2001).

2.2 Structural Equations Explained

A structural equation model approach using Partial

Least Squares (PLS) (Ringle, Wende, & Will, 2005)

is used to test the hypotheses of this study. PLS is

based on an iterative combination of principal

components analysis and regression, and it aims to

explain the variance of the constructs in the model.

In terms of advantages, PLS simultaneously

estimates all path coefficients and individual item

loadings in the context of a specified model, and as a

result, it enables researchers to avoid biased and

inconsistent parameter estimates. Based on recent

developments (Chin, Marcolin, & Newsted, 2003),

PLS has been found to be an effective analytical tool

to test interactions by reducing type II error. By

creating a latent construct which represents the

interaction term, a PLS approach significantly

reduces this problem by accounting for the error

related to the measures. In fact, PLS models are

based on prediction-oriented measures, not

covariance fit like covariance structure models

developed by Karl Jöreskog, or LISREL program

developed by Jöreskog and Sörborn.

LISREL estimates causal model parameters

aiming at minimizing the discrepancies between the

initial empirical covariance data matrix and the

covariance matrix deduced from the model structure

and the parameter estimates (Barclay, Higgins, &

Thompson, 1995). PLS seeks to maximize variance

explained in constructs and/or variables, depending

on model specification. In addition, LISREL offers a

number of measures of overall model “fit” such as

the χ

2

goodness-of-fit, which are related to the

ability of the model to account for the sample

covariance. PLS does not possess these kind of

overall fit measures, relying instead on variance

explained (i.e., R

2

) as an indicator of how well the

technique has met its objective (Barclay et al.,

1995). In spite of that, there are several fit indices

available on PLS software (Ringle et al., 2005) such

as communality and redundancy measures and

Stone-Geisser’s Q

2

measure, which can be used to

evaluate the predictive power of the model.

As a substitute to parametric global goodness of

fit measures that are used in LISREL technique, the

geometric mean of the average communality (outer

model) and the average R

2

(inner model) (going

from 0 to 1) has been proposed (Tenenhaus, Vinzi,

Chatelin, & Lauro, 2005) as overall goodness of fit

(GoF) measures for PLS (Cross validated PLS GoF),

according to equation (1).

2

.GoF communality R=

(1)

2.3 Hypothesis Proposed

Five hypotheses are formulated in this study and

tested with PLS:

H1: Web site brand personality significantly and

positively influences web site brand image

H2: Web site brand association significantly and

positively influences web site brand image

WEBIST 2010 - 6th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

258

H3: Web site brand image significantly and

positively influences web site brand relationship

H4: Web site brand image significantly and

positively influences consumer loyalty

H5: Web site brand relationship significantly and

positively influences consumer loyalty

3 METHODS

3.1 Participants and Procedure

The surveys were conducted in June 2008 through

face-to-face interviews in universities in Spain and

Scotland. The same two interviewers, specially

trained, were used in the two countries. We choice

Spain and Scotland to consider different cultural

contexts.We collected 95 completed questionnaires

from students in Spain and 100 from students in

Scotland. Each sub-sample has the same average age

of 24 years. The respondents split almost equally in

terms of gender for both countries.

In this study, the web site brands involved

belong to different industry branch, such as: clothes,

books, music, and airlines.

3.2 Measures

Web site brand association was measured using two

dimensions (product and organization) (Barclay et al.,

1995; Carmines & Zeller, 1979)

. Web site brand

personality was operationalized using 5 dimensions

(sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication,

and ruggedness) (Aaker, 1997), web site brand

image with 3 dimensions (function, experience, and

symbolic) (Chang & Chieng, 2006; Keller, 1993),

web site brand relationship with 6 dimensions

(functional, love, commitment, attachment, self-

connection, and partner quality) (Chang & Chieng,

2006), and loyalty with 2 dimensions (recommend

and by again) (Zeithaml et al., 1996). Each statement

of the questionnaire was recorded on a 5-point

Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree).

The instrument was elaborated in English and

translated to Spanish using a dual focus method

(Erkut, Alarcón, Coll, Tropp, & Garcia, March

1999).

3.3 Data Analysis

The PLS model is analyzed and interpreted in two

stages. First, the adequacy of the measures is

assessed by evaluating the reliability of the

individual measures and the discriminant validity of

the constructs (Hulland, 1999). Then, the structural

model is appraised.

Composite reliability is used to analyze the

reliability of the constructs since this has been

considered a more exact measurement than the

Cronbach’s alpha (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). To

determinate convergent validity, we compute the

average variance of manifest variables extracted by

constructs (AVE) that should be at least 0.5,

indicating that more variance is explained than

unexplained in the variables associated with a given

construct. To assess discriminant validity we follow

the rule that the square root of AVE should be

greater than the correlation between the construct

and other constructs in the model (Fornell &

Larcker, 1981).

Bootstrap (a nonparametric approach) is used to

estimate the precision of the PLS estimates and

support the hypotheses. Accordingly, 500 samples

sets were created in order to obtain 500 estimates for

each parameter in the PLS model. Each sample was

obtained by sampling with replacement to the

original data set (Chin, 1998; Fornell & Larcker,

1981).

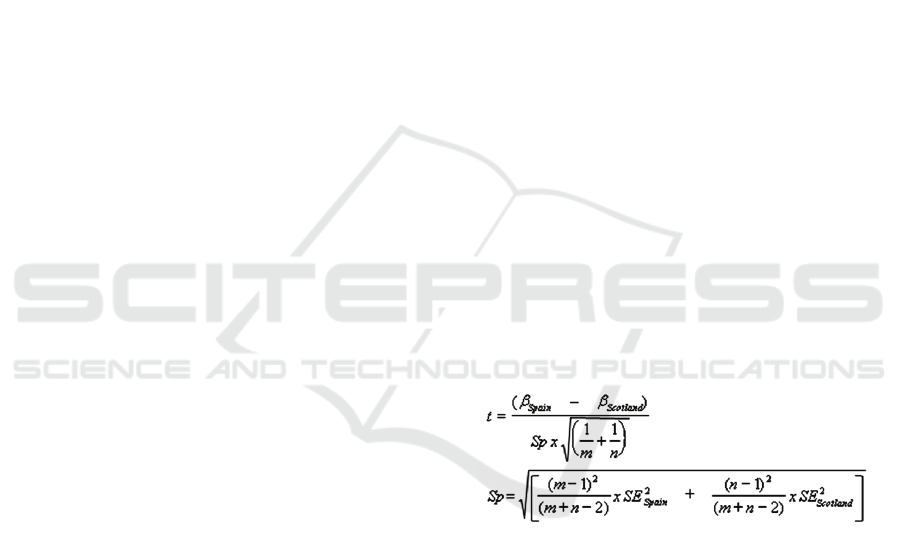

Finally, the differences between the Scottish and

the Spanish samples are compared using a t-test of

m+n+2 degrees of freedom (where m=Spain sample

size and n=Scotland sample size). This test uses the

path coefficients and the standard errors of the two

structural paths calculated by PLS with the samples

of both countries, according to equation (2).

(2)

4 RESULTS

All the loadings of reflective constructs approach or

exceed 0.707 (Table 1), which indicates that more

than 50% of the variance in the manifest variable is

explained by the construct (Carmines & Zeller,

1979), except for the construct brand personality and

brand relationship. Ruggedness, functional,

attachment, self connection and partner quality were

eliminated from the Scottish sample. Results in

Table 1 shows that all constructs are reliable since

the composite reliability values exceed the threshold

of 0.7 and even the strictest one of 0.8 (Nunnally,

1978).

WEB SITE BRAND ATTRIBUTES AND E-SHOPPER LOYALTY - A Comparative Study of Spain and Scotland

259

The measures also demonstrate convergent

validity and discriminant validity (Table 2),

according to the criteria defined in Methods.

The structural results for Spain are presented in

Figure 1. All the path coefficients are found to be

significant at the 0.001 level and all the coefficients’

signs are in the expected direction, excepting for the

causal order between brand image and loyalty.

Multiplication of the Pearson correlation value

for the path coefficient value of each of the two

constructs reveals that 49.4% of the brand image

variability is explained by brand association, 34.1%

of the brand relationship variability is explained by

brand image, and 18.6% of the loyalty variability is

explained by brand relationship.

Brand

Association

Brand

Relationship

R

2

= 34.1 %

Q

2

= 0.190

Brand

Image

R

2

= 68.4 %

Q

2

= 0.474

Brand

Personality

Loyalty

R

2

= 18.3 %

Q

2

= 0.153

0.584***

34.1 %

0.631***

49.4 %

0.308***

19.0 %

-0.011ns

-0.3 %

0.434***

18.6 %

GoF

Spain

= 0.5374

*** p < 0.001 ; ns : n o significant

Figure 1: Structural results for Spain.

Brand

Association

Brand

Relationship

R

2

= 36.0 %

Q

2

= 0.292

Brand

Image

R

2

= 60.6 %

Q

2

= 0.394

Brand

Personality

Loyalty

R

2

= 40.6 %

Q

2

= 0.325

0.600***

36.0 %

0.438***

31.7 %

0.404***

28.9 %

0.430***

25.7 %

0.278**

14.9 %

GoF

Scotland

= 0.5932

*** p < 0.001 ; ** p < 0.01

Figure 2: Structural results for Scotland.

Table 1: Measurement Results.

Variable

LV

Index

Values

Item

Loading

Composite

reliability

AVE

Spain

Brand association

3.5

0.843

0.729

AS1:Product 0.909

AS2:Organization 0.795

Brand personality

3.4

0.901

0.646

PS1:Excitement 0.822

PS2: Sophistication 0.763

PS3: Ruggedness 0.802

RS4:Sincerity 0.793

RS5: Competence 0.836

Brand Image 3.3 0.874

0.698

IS1: Function 0.777

IS2: Experience 0.889

IS3:Symbolic 0.837

Brand Relationship 2.8 0.903 0.609

RS1:Functional 0.710

RS2:Love 0.867

RS3:Commitment 0.833

RS4:Attachment 0.744

RS5:Self Connection 0.727

RS6:Partner quality 0.789

Loyalty 3.8 0.949 0.903

LS1:Recommendation 0.967

LS2:By again 0.933

Scotland

Brand association

3.6

0.954

0.912

ASc1:Product 0.954

ASc2:Organization 0.956

Brand personality

3.3

0.886

0.682

PSc1:Excitement 0.880

PSc2: Sophistication 0.730

PSc3: Sincerity 0.837

PSc4: Competence 0.799

Brand Image 3.2 0.867

0.686

ISc1: Function 0.781

ISc2: Experience 0.837

ISc3:Symbolic 0.864

Brand Relationship 2.8 0.902 0.821

RSc1:Love 0.891

RSc2:Commitment 0.927

Loyalty 3.6 0.868 0.768

LSc1:Recommendation 0.921

LSc2:By again 0.830

The structural results for Scotland are presented in

Figure 2. All the path coefficients are significant at

the 0.001 level and all the coefficients’ signs are also

in the expected direction, excepting for the causal

order between brand relationship and loyalty which

is significant at the 0.01 level. As in the Spanish

sample, the Bootstrap approach with n = 500 was

used and all the hypothesized relations were

supported. Multiplication of the Pearson correlation

value for the path coefficient value of each of the

two constructs reveals that 31.7% of the brand image

variability is explained by brand association, 36.0%

of the brand relationship variability is explained by

WEBIST 2010 - 6th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

260

Table 2: Discriminant validity: square root of AVE and

correlations of constructs.

Correlations of constructs

Construct

Brand

associati

on

Brand

image

Brand

perso

nality

Brand

relations

hip

Loyalty

Spain

AVE

1/2

0.96 0.83 0.81 0.91 0.88

Brand

association 1.00 0.72 0.71 0.47 0.50

Brand image

0.72 1.00 0.71 0.60 0.60

Brand

personality 0.71 0.71 1.00 0.55 0.54

Brand

relationship 0.47 0.60 0.55 1.00 0.54

Loyalty 0.50 0.60 0.54 0.54 1.00

Scotland

AVE

1/2

0.85 0.84 0.80 0.78 0.95

Brand

association 1.00 0.78 0.49 0.43 0.31

Brand image

0.78 1.00 0.62 0.58 0.24

Brand

personality 0.49 0.62 1.00 0.60 0.46

Brand

relationship 0.43 0.58 0.60 1.00 0.43

Loyalty 0.31 0.24 0.46 0.43 1.00

brand image, and 25.7% of the loyalty variability is

explained by brand image.

The results of t-test (Table 3) show that there are

not statistically significant differences between the

two countries in any of the two structural paths (at

critical t-value=|1.960|), excepting for the causal

order between brand image and loyalty.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study represents the first attempt to considerer

the web site brand in a structural model using the

PLS approach, which analyzes simultaneously the

causal orders among web site brand association, web

site brand image, web site brand personality, web

site brand relationship, and loyalty.

The results show that web site brand association

and web site brand personality are good predictors

of web site brand image and that the hypotheses H1

and H2 are confirmed for the Scottish and the

Spanish samples. Hypotheses H3 and H5 are also

supported, but the hypothesis H4 is not supported by

the Spanish sample. Thus, web site brand

relationship seems to be more important than brand

image in explaining the intention to recommend the

web site and to buy again. The Scottish students give

more importance to web site brand image than the

Spanish students. However, web site brand

Table 3: Results of multi-group analysis: Spain and

Scotland.

Structural

paths

Standard

error

Spain

Standard

error

Scotland

Sp

1

β

Spain

-

β

Scotland

t-test

Brand

association

→ Brand

image

0.098 0.095 0.950 0.192 1.414

Brand

personality

→ Brand

image

0.090 0.097 0.921 -0.097

-

0.733

Brand

image →

Brand

relationship

0.091 0.060 0.749 -0.016

-

0.147

Brand

image →

Loyalty

0.132 0.098 1.137 -0.441

-

2.709

Brand

relationship

→ Loyalty

0.115 0.099 1.048 0.157 1.044

1 Unbiased estimator of average error standard variance

association exercises a stronger effect on web site

brand image than the web site brand personality, for

the two groups of students in the different countries.

Traditionally, brand image and brand personality

are different constructs. However, the PLS technique

seems to give evidence of some correlation between

the competence (eliminated in this analyze) of brand

personality and the symbolic part of brand image.

Further directions for future work have been

indicated by this first study of web site brand

knowledge. The model is being redesigned to

include other constructs and we are planning to

extend our research to other countries, such as

Brazil, USA, Germany, Portugal and Poland. With a

cross-country approach we will be able to analyze

the impact of culture on consumers’ perception and

test the effect of globalization, advancing existing

knowledge and generating valuable information for

decision makers, marketers and web designers.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on

the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press.

Aaker, J. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality.

Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 347-356.

Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson. (1995). The partial

least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling,

personal computer adoption and use as an illustration.

Technology Studies, 2, 285-309.

WEB SITE BRAND ATTRIBUTES AND E-SHOPPER LOYALTY - A Comparative Study of Spain and Scotland

261

Bart, Y., Shankar, V., Sultan, F., & Urban, G. (2005). Are

the drivers and the role of online trust the same for all

web sites and consumers? A large-scale exploratory

empirical study. Journal of Marketing, 69, 133-152.

Carmines, E., & Zeller, R. (1979). Reliability and Validity

Assessment. London: Ed. Sage Publications, Inc.

Chang, P.-L., & Chieng, M.-H. (2006). Building

consumer-brand relationship: A cross-cultural

experential view. Psychology and Marketing, 23(11),

927-959.

Chin, W. (1998). The Partial Least Squares approach to

structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides

(Ed.), Modern Methods for Business Research (pp.

295-336). NJ: Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Publisher.

Chin, W., Marcolin, B., & Newsted, B. (2003). A partial

least squares latent variable modelling approach for

measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte

Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail emotion/

adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2),

189-217.

Erkut, S., Alarcón, O., Coll, C., Tropp, L., & Garcia, H. A.

V. (March 1999). The dual-focus approach to creating

bilingual measures. Journal of Cross-Cultural

Psychology, 30(2), 206-218.

Fornell, & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural

models with unobservables variables and measurement

error. Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 39-50.

Hsieh, M. (2002). Identifying brand image dimensionality

and measuring the degrees of brand globalization: A

cross-nation study. Journal of International

Marketing, 10, 46-67.

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in

strategic management research: a review of four recent

studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195-

204.

Keller, K. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring,, and

managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of

Marketing, 57, 1-22.

Keller, K. (1998). Strategic brand management: Building,

measuring and managing brand equity. New York:

Prentice Hall.

Keller, K. (2003). Brand synthesis: the

multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of

Consumer Research, 29(4), 595-600.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric Theory (2nd ed.). New

York: McGraw-Hill.

O'Cass, A., & Lim, K. (2001). The influence of brand

association on brand preference and purchase

intention: As Asia perspective on brand association.

Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 14, 41-

71.

Plummer, J. (2000). How personality makes a difference.

Journal of Advertising Research, 40(6), 79-83.

Ringle, C., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2005). SmartPLS 2.0

(beta). from www.smartpls.de

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, E., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C.

(2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics

& Data Analysis, 48, 159-205.

Zeithaml, V., Berry, L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The

behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of

Marketing, 60(2), 31-46.

WEBIST 2010 - 6th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

262