WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM BASED ON

A CONTEXT SENSITIVE VARIANT DICTIONARY

Aya Nishikawa, Ryo Nishimura, Yasuhiko Watanabe, Yoshihiro Okada

Ryukoku University, Dep. of Media Informatics, Seta, Otsu, Shiga, Japan

Masaki Murata

NICT, Seika-cho, Soraku-gun, Kyoto, Japan

Keywords:

Writing support system, Notational variant, Context suitable variant, Context sensitive dictionary.

Abstract:

In Japanese, it is difficult to learn which variant is suitable for various contexts in official, business, and

technical documents because there are a large number of notational variants of Japanese words and Japanese

writing rules have many exceptions. From the viewpoint of information retrieval, a considerable number of

studies have been made on notational variants, however, previous Japanese writing support systems were not

concerned with them sufficiently. To solve this problem, we developed a writing support system which detects

notational variants unsuitable for the contexts in students’ reports and shows suitable ones to the students.

This system is based on the idea that context suitable variants are used dominantly in the context of official,

business, and technical documents. In this study, we first show the diversity of notational variants of Japanese

words and how to develop a context sensitive variant dictionary by which our system determines which variant

is suitable for the contexts in official, business, and technical documents. Finally, we conducted a control

experiment and show the effectiveness of our system.

1 INTRODUCTION

In English, there are few words which are spelled in

several different ways, such as, color and colour. In

contrast, in Japanese, there are a large number of no-

tational variants of words. This is because Japanese

words are written in three kinds of characters:

• kanji (Chinese) characters,

• hiragara letters, and

• katakana letters.

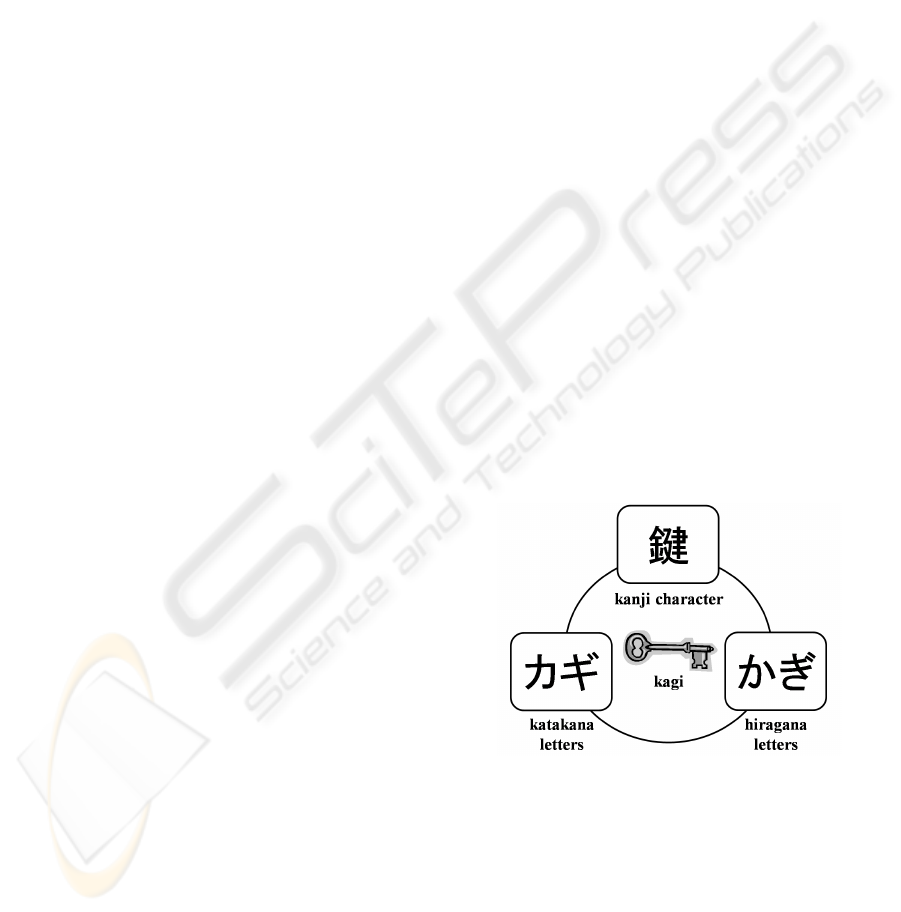

For example, kagi [key] is written in three ways, as

shown in Figure 1. Basic rules of Japanese writing

are announced by the Cabinet, and Japanese students

study them in school for many years. However, it is

difficult to learn the rules because they have many

exceptions. In fact, we often find the confusion of

variant selection in Japanese university students’ re-

ports, including unsuitable notational variants for of-

ficial, business, and technical documents. As a result,

it is important for students to learn which notational

variant is suitable for official, business, and techni-

cal documents. To solve this problem, (Nishikawa

Figure 1: Notational variants of “kagi [key]”.

09a) developed a writing support system which de-

tects unsuitable notational variants in students’ re-

ports and shows suitable ones to the students. This

system is based on the assumption that suitable vari-

ants are used dominantly in official, business, and

technical documents. If the assumption is proper, un-

suitable notational variants can be detected by con-

firming whether they are used dominantly in official,

business, and technical documents. We think the sys-

251

Nishikawa A., Nishimura R., Watanabe Y., Okada Y. and Murata M. (2010).

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM BASED ON A CONTEXT SENSITIVE VARIANT DICTIONARY.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education, pages 251-256

DOI: 10.5220/0002789702510256

Copyright

c

SciTePress

hiragana katakana kanji

kagi

[key] 1 279 198

Figure 2: The frequencies of notational variants of noun

“kagi [key]” in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspaper

(January 2006 – June 2006)].

hiragana katakana kanji

kagi

[key] 0 10 64

Figure 3: The frequencies of notational variants of noun

“kagi [key]” in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspaper

(2005 – 2007)] in the case that the word is used with “kakeru

[lock]”.

tem of (Nishikawa 09a) is promising, however, it has

a problem: The system was based on a context free

variant dictionary. As a result, it is possible that the

system lets users select variants which are most fre-

quent but unsuitable for the contexts. Take kagi [key]

for example. As shown in Figure 2, in newspaper ar-

ticles, kagi is dominantly written in katakana letters.

However, as shown in Figure 3, kagi is dominantly

written in a kanji character when it is used with kakeru

[lock]. As a result, it is important that writing sup-

port systems show variant information of Figure 3,

not Figure 2, when kagi [key] and kakeru [lock] are

used together. To solve this problem, we developed

a writing support system based on a context sensitive

variant dictionary.

Our system shows the frequencies of notational

variants to students because they are objective and

concrete measures. As a result, the system gives stu-

dents chances to consider the reasons why they used

variants unsuitable for the contexts. There are two

reasons why our system does not replace unsuitable

variants to context suitable ones automatically.

• it is not appropriate to restrict the use of various

variants because it is one of the sources of the

richness of Japanese expressions.

• it is important to consider the reasons why they

used variants unsuitable for the contexts and

choose context suitable ones, especially, in edu-

cational institutions.

From the viewpoint of information retrieval, a

considerable number of studies have been made

on notational variants (Kubomura 03) (Kouda 06)

(Bamba 08), however, spell checkers in Japanese

word processor, such as Microsoft word 2007, and

previous Japanese writing support systems were not

concerned with notational variants sufficiently (Shi-

momura 92) (Araki 93) (Murata 01). This is because

their main purposes were misspelling detection. Stu-

dents often use variants which are not misspelling,

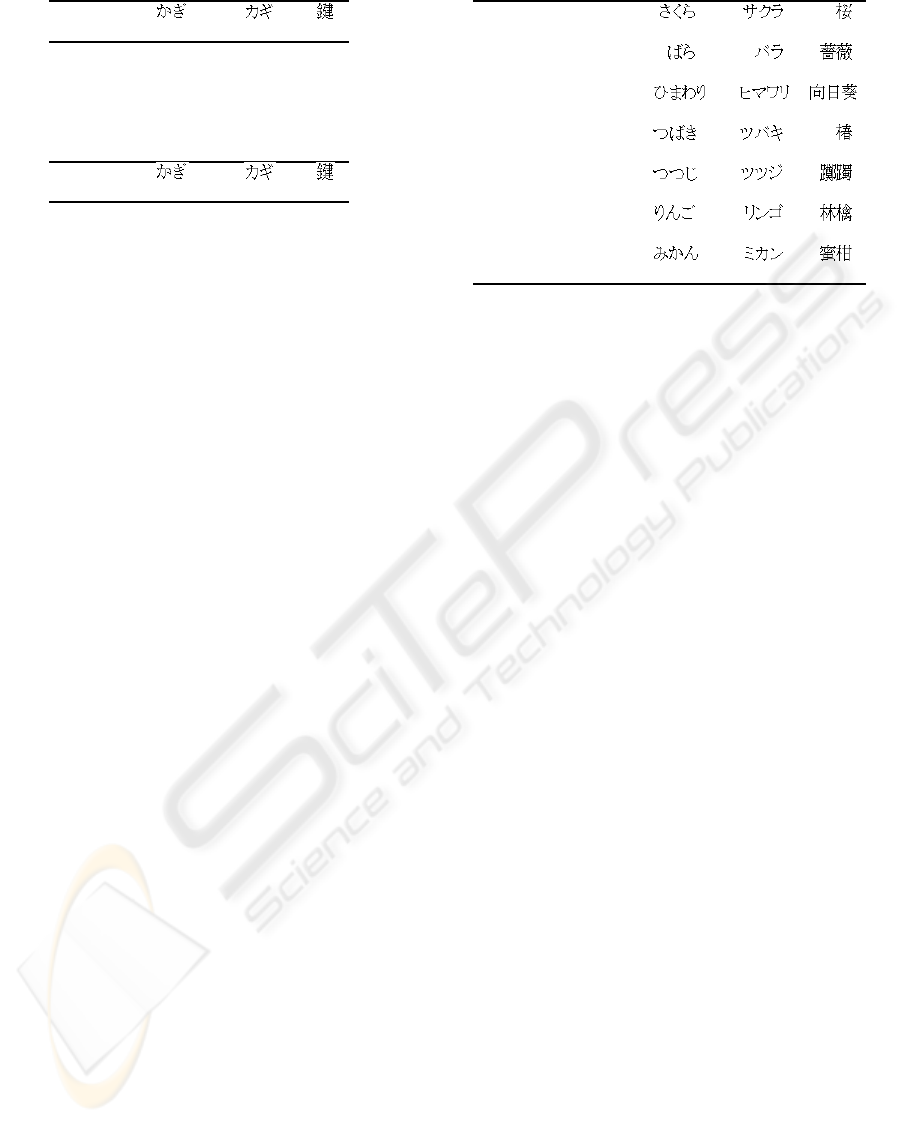

names of plants hiragana katakana kanji

sakura

[cherry blossom] 184 39 736

bara

[rose] 0 217 0

himawari

[sun flower] 42 8 0

tsubaki

[camellia] 9 25 83

tsutsuji

[azalea] 5 15 0

ringo

[apple] 8 71 10

mikan

[orange] 66 37 2

Figure 4: The frequencies of notational variants of nouns

(plant names) in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspa-

per (January 2006 – June 2006)].

however, unsuitable for the contexts in official, busi-

ness, or technical documents. In contrast, Yokoyama

dealt with variants of kanji characters (Yokoyama06),

but not with variants of words. Furthermore, he did

not consider this variant problem from the viewpoint

of contexts.

In this study, we first show the diversity of no-

tational variants of Japanese words and how to de-

velop a context sensitive variant dictionary by which

our system determines which variant is suitable for

the context in official, business, and technical docu-

ments. Finally, we conducted a control experiment

and show the effectiveness of our system.

2 NOTATIONAL VARIANTS OF

JAPANESE WORDS

In this section, we show the diversity and exceptions

of notational variants of Japanese words.

First, we show the diversity and exceptions of no-

tational variants of Japanese nouns. We have shown

an example of notational variants of Japanese nouns,

kagi [key], in section 1. Furthermore, Figure 4 shows

the frequencies of notational variants of plant names

in the Mainichi newspaper articles (January 2006 –

June 2006). As shown in Figure 4, dominant ways

of writing plant names are inconsistent. In this study,

we will use the term dominant variant of a word to

refer to the most frequent variant of the word, as

(Nishikawa 09a) did. One of the reasons of this in-

consistent is that writers choose variants considering

the contexts.

Next, we show the diversity and exceptions of no-

tational variants of Japanese declinable words. Figure

5 shows the frequencies of notational variants of hiki-

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

252

hiragana kanji+(1) kanji+(2) kanji+(3)

hikiageru

[pull up] 1 4 774 146

Figure 5: The frequencies of notational variants of verb

“hikiageru [pull up]” in the newspaper articles [Mainichi

Newspaper (January 2006 – June 2006)].

hiragana kanji+(1) kanji+(2) kanji+(3)

hikiageru

[pull up] 0 0 2 15

Figure 6: The frequencies of notational variants of verb

“hikiageru [pull up]” in the newspaper articles [Mainichi

Newspaper (2005 – 2007)] in the case that the word is used

with “toushi [investment]”.

ageru [pull up] in the Mainichi newspaper articles. As

shown in Figure 5, is the dominant variant

of hikiageru [pull up]. However, as shown in Fig-

ure 6, a nondominant variant of hikiageru, ,

is used dominantly when hikiageru is used with tou-

shi [investment]. This kind of exceptions often con-

fuse learners of Japanese, not only foreign students

but Japanese students. In fact, the authors are often

confronted with the confusion of variant selection in

their reports.

3 WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM

BASED ON A CONTEXT

SENSITIVE VARIANT

DICTIONARY

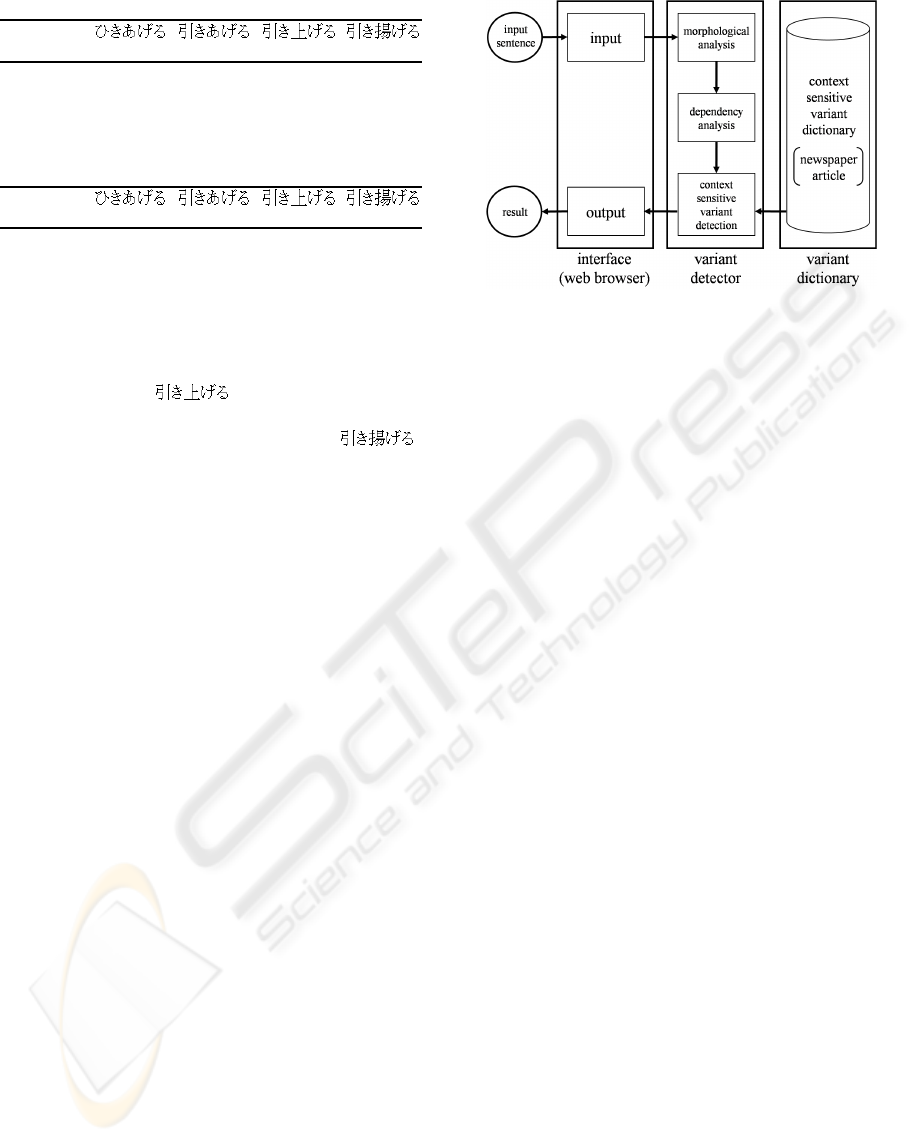

3.1 System Overview

Figure 7 shows the overview of our system based on

a context sensitive variant dictionary. Figure 8 shows

an example of how to use our writing support sys-

tem. As shown in Figure 7, users can access and send

input sentences to the system via web browsers by

using CGI based HTML forms. Input sentences are

segmented into words by using a Japanese morpho-

logical analyzer, JUMAN (JUMAN 05). Then, the

dependency relations between the words were ana-

lyzed by using a Japanese parser, KNP(KNP 05). Fi-

nally, by using the context sensitive variant dictionary,

the system confirms whether variants are suitable for

the contexts in official, business, and technical docu-

ments. When the system detects a variant unsuitable

for the context in an input sentence, the system un-

derlines and turns it red, shows the frequency infor-

mation of the variant in the context, and gives users

chances to consider the reasons why they used the

Figure 7: System overview.

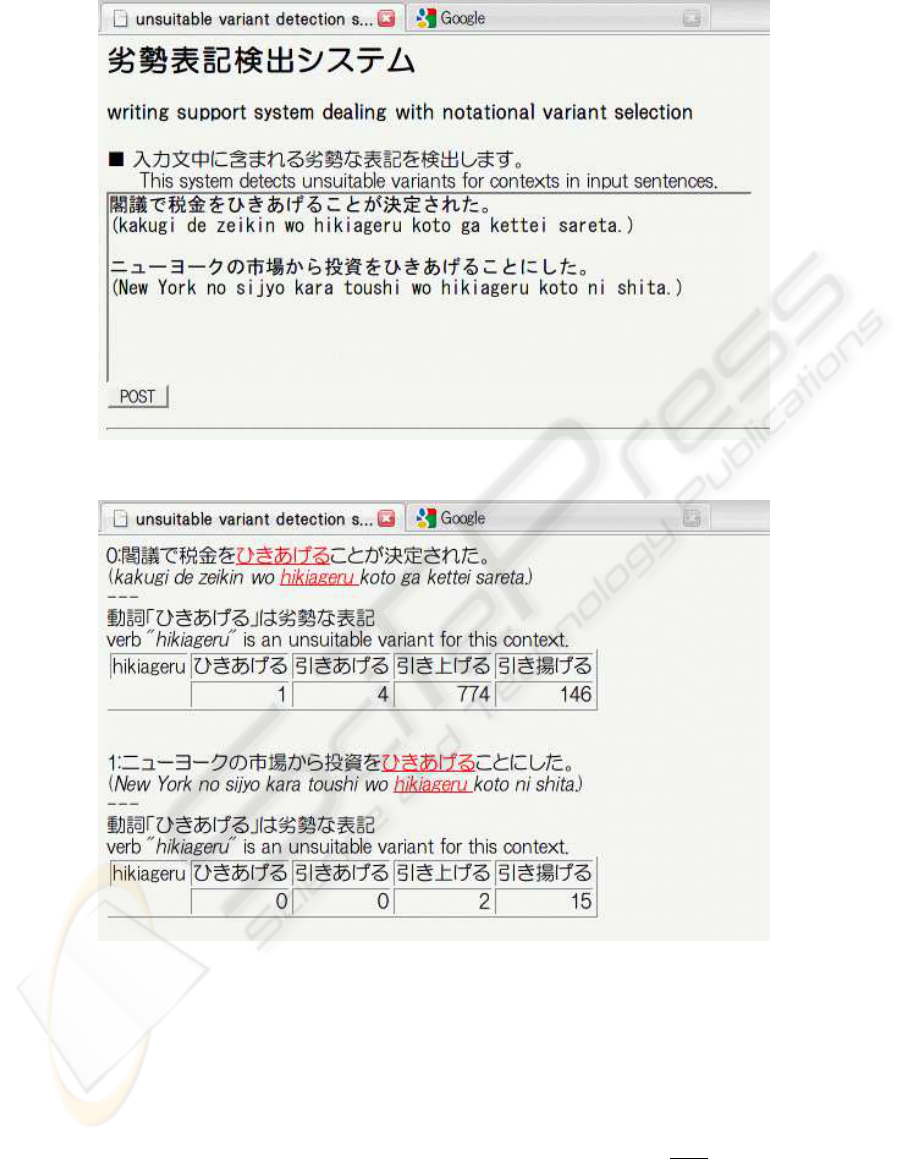

variant. In Figure 8 (a), a user gives the following

two input sentences to the system.

• kakugi de zeikin wo hikiageru koto ga kettei sareta

[the plan to raise taxes was approved by the Cabi-

net]

• New York no sijyo kara toushi wo hikiageru koto

ni shita [we decided to withdraw our investments

from the New York market]

Then, as shown in Figure 8 (b), the system detects that

variants of hikiageru in both input sentences are un-

suitable for the contexts. In each sentence, the variant

of hikiageru is underlined and turns red, and the con-

text sensitive frequency information of the variant is

shown. In this way, the key to detecting variants un-

suitable for the contexts is a context sensitive variant

dictionary. In section 3.2, we show how to develop a

context sensitive variant dictionary.

3.2 Context Sensitive Variant

Dictionary

In order to develop a context sensitive variant dic-

tionary, we expand a context free variant dictionary

by adding information of context suitable variants

and the contexts. The context free variant dictionary

(Nishikawa 09b), which we used and expanded in

this study, contains dominant variants of 20929 words

which were extracted from 296364 articles published

in the Mainichi Newspaper from January 2006 to June

2006 (Mainichi 06-08) credibly by using binomial

tests. These words can be classified into two types:

TYPE I a word of this type has actually two or more

variants, however, only one of them was found in

the newspaper articles. 14659 TYPE I words were

extracted from the Mainichi Newspaper (January

2006 – June 2006).

TYPE II a word of this type has two or more vari-

ants found in the newspaper articles. 6270 TYPE

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM BASED ON A CONTEXT SENSITIVE VARIANT DICTIONARY

253

(a) two input sentences, both of which include “hikiageru [pull up]”, are given to the system.

(b) the system detects unsuitable variants of “hikiageru [pull up]” for the contexts in the input sentences

and shows the context sensitive frequency information of the variants.

Figure 8: An example of how to use our writing support system. English system messages are inserted ad hoc for convenience

of non-Japanese readers of this paper.

II words were extracted from the Mainichi News-

paper (January 2006 – June 2006). Words which

have context suitable variants are classified into

TYPE II words.

In order to show how much the dominant variant of a

word is used dominantly, (Nishikawa 09b) introduced

dominant degree. Suppose that a word has variant i

(∈ I) and the utilization rate of variant i is calculated

as follows:

u

i

=

f

i

∑

i∈I

f

i

where u

i

and f

i

is the utilization rate and frequency

of variant i, respectively. The dominant degree of the

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

254

0

20

40

60

80

100

0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

word frequency

dominant degree

TYPE II words (extracted by binomial test)

TYPE II words (all)

Figure 9: The histograms of the dominant degrees of TYPE

II words in the newspaper articles [Mainichi Newspaper

(January 2006 – June 2006)].

word is calculated as follows:

d = max

i∈I

u

i

where d is the dominant degree of the word. Figure

9 shows the histograms of the dominant degrees of

TYPE II words extracted from the Mainichi Newspa-

per (January 2006 – June 2006). The broken line in

Figure 9 shows the histogram of the dominant degrees

of all the TYPE II words extracted from the Mainichi

Newspaper (January 2006 – June 2006). On the other

hand, the thick line shows the histogram of the domi-

nant degrees of TYPE II words the variants of which

were extracted credibly by using binomial tests from

the Mainichi Newspaper (January 2006 – June 2006).

We expanded this variant dictionary by adding the fol-

lowing kinds of information

• context suitable variants and

• the contexts where the variants are used domi-

nantly.

The information was extracted in the next way.

Suppose that word A has a variant which is a non-

dominant variant of word A but is used dominantly in

the context that word A is used with B. We extracted

• the context suitable variant of word A and

• the context that word A is used with word B

in the next steps.

Step 1 apply Japanese morphological analysis and

dependency analysis to newspaper articles. In

this study, we used a Japanese morphological an-

alyzer, JUMAN (JUMAN 05) and a Japanese

parser, KNP(KNP 05).

Step 2 From the results of the analyses, extract vari-

ants of word A which have the dependency rela-

tion to word B. In the morphological analysis, JU-

MAN gives variant labels to variants. Variants of

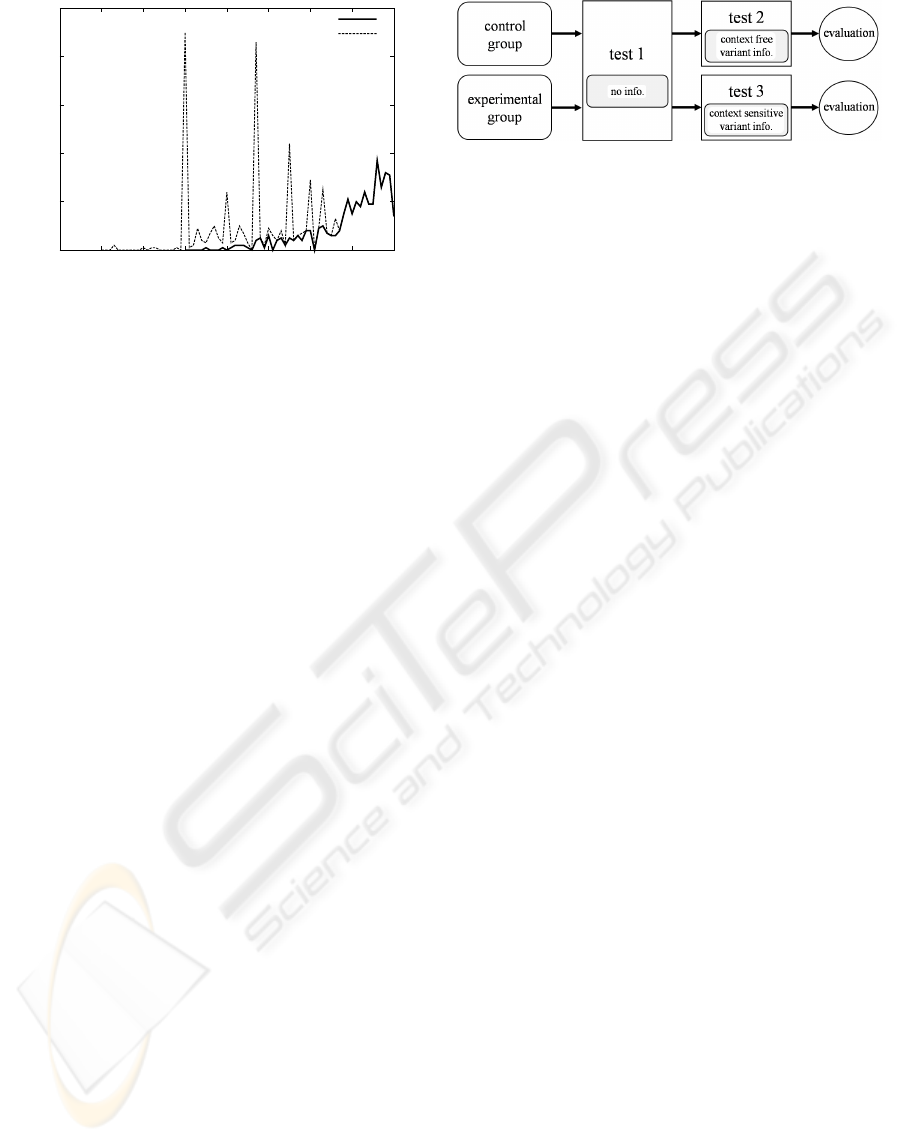

Figure 10: The outline of the experiment.

a certain word can be detected because JUMAN

gives the same variant label to them.

Step 3 determine which variant of word A is used

dominantly in the context that word A is used with

word B. If the variant is not the dominant variant

of word A, go step 4. Otherwise, terminate the

process. The dominant variant of word A is regis-

tered in the variant dictionary (Nishikawa 09b).

Step 4 In order to confirm that the variant is a cred-

ible context suitable variant, measure the credi-

bility of the context suitable variant by using bi-

nomial tests: the variant is regarded as a credi-

ble context suitable variant, when the lower limits

of one-sided 95% binomial confidence interval of

the utilization rates of the variant in the context is

more than 0.5.

In this study, we extracted 3598 context suitable

variant and the contexts from 1786752 articles pub-

lished in the Mainichi Newspaper from 2005 to 2007

(Mainichi 06-08).

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

To evaluate our method, we conducted a control ex-

periment. Figure 10 shows the outline of the ex-

periment. 20 subjects, university students in com-

puter science, were classified into two groups: control

group and experimental group. As shown in Figure

10, we conducted test 1 and 2 to the control group,

and test 1 and 3 to the experimental group. In these

three tests, we gave the same five problems of variant

selection with the following kinds of information:

test 1 no information

test 2 context free variant information

test 3 context sensitive variant information

Each problem consisted of two sentences, one word

of which was underlined, and variant choices of the

word. From the variant choices of the underlined

word, the subjects were requested to choose one vari-

ant which seemed to be suitable for the contexts in

official, business, and technical documents. One sen-

tence in each problem had a context for which the

WRITING SUPPORT SYSTEM BASED ON A CONTEXT SENSITIVE VARIANT DICTIONARY

255

Table 1: The choosing rate of variants suitable for the con-

texts.

group test 1 test 2 / 3

control 68% 77%

experimental 73% 81%

dominant variant was suitable. The other had a con-

text for which the dominant variant was not suitable.

For example, the following two sentences were used

in a problem of the experiment.

Problem 1(a) kakugi de zeikin wo hikiageru koto ga

kettei sareta [the plan to raise taxes was approved

by the Cabinet]

Problem 1(b) New York no sijyo kara toushi wo

hikiageru koto ni shita [we decided to withdraw

our investments from the New York market]

The dominant variant of hikiageru [pull up] is suitable

for the context of problem 1(a), on the other hand, un-

suitable for the context of problem 1(b) because hiki-

ageru was used with toushi [investment]. When sub-

jects in the control group tried to solve problem 1(a)

and 1(b) in test 2, they received the frequency infor-

mation which is shown in Figure 5 and unsuitable for

the context of problem 1(b). On the other hand, sub-

jects in the experimental group received context sen-

sitive frequency information which

• is shown in Figure 5 when they tried to solve prob-

lem 1(a) in test 3

• is shown in Figure 6 when they tried to solve prob-

lem 1(b) in test 3

In other words, subjects in the experimental group re-

ceived the same context sensitive frequency informa-

tion which our system gives to users. Figure 8 (b)

shows the advices of our system when problem 1(a)

and 1(b) are given to the system.

Table 1 shows the choosing rate of variants suit-

able for the contexts in test 1, 2, and 3. Table 1 shows

that the notational variant selection is a serious prob-

lem. In test 1, some subjects chose unsuitable variants

for no particular reason and they were totally unaware

of doing it. However, Table 1 also implies that stu-

dents do not have confidence in their notational vari-

ant selection and flexibly change their decisions when

the reasons are given to them. Actually, in test 3,

five subjects in the experimental group changed their

decisions, and two other subjects did not change but

felt sure of their decisions. Some of them said that

they could obey system’s advices more simply than

teacher’s instructions without concrete evidences. On

the other hand, in test 2, five subjects in the control

group changed their decisions, and two of them se-

lected variants unsuitable for the contexts because of

the context free variant information.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we first proposed a method of devel-

oping a context sensitive variant dictionary by which

our writing support system determines which variant

is suitable for the contexts in official, business, and

technical documents. Then, we conducted a control

experiment and show the effectiveness of our system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been supported partly by the

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) under Grant

No.20500106.

REFERENCES

Nishikawa, Nishimura, Watanabe, and Okada: Writing

Support System Dealing with Notational Variant Se-

lection, CSEDU 2009, (2009).

Nishikawa, Nishimura, Watanabe, Murata, and Okada:

Dominant Variant Dictionaries for Supporting Variant

Selection, IADIS AS 2009, (2009).

Kubomura and Kameda: Information Retrieval System with

Abilities of Processing Katakana-Allographs, Trans.

of IEICE, Vol.J86-D-II, No.3, (2003).

Kouda: Search method of variant notations on a science and

technology document retrieval system, IPSJ SIG NL,

Vol.2006, No.118, (2006).

Bamba, Shinzato, and Kurohashi: Development of a Large-

scale Web Page Clustering System using an Open

Search Engine Infrastructure TSUBAKI, IPSJ SIG

NL, Vol.2008, No.4, (2008).

Shimomura, Namiki, Nakagawa, and Takahashi: A method

for detecting errors in Japanese sentences based

on morphological analysis using minimal cost path

search, Trans. of IPSJ, Vol.33, No.4, (1992).

Araki, Ikehara, and Tukahara: A method for detect-

ing and correcting of characters wrongly substituted,

deleted or inserted in Japanese strings using 2nd-order

Markov model, IPSJ SIG NL, Vol.93, No.79, (1993).

Murata and Isahara: Extraction of negative examples based

on positive examples: automatic detection of mis-

spelled Japanese expressions and relative clauses that

do not have case relations with their heads, IPSJ SIG

NL, Vol.2001, No.69, (2001).

Yokoyama: Can we predict preference for kanji form from

newspaper data on character frequency?, IPSJ SIG

CH, Vol.2006, No.10, (2006).

Kurohashi and Kawahara: JUMAN Manual version 5.1 (in

Japanese), Kyoto University, (2005).

Kurohashi and Kawahara: KNP Manual version 2.0 (in

Japanese), Kyoto University, (2005).

Mainichi Shinbun CD-Rom data set 2005, 2006, and 2007,

Nichigai Associates Co., (2006-2008).

CSEDU 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

256