UNDERSTANDING CHANGES IN HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE

Can We Provide Tools & Methods for Visual Reasoning?

I. Dudek and J. Y. Blaise

UMR CNRS/MCC 694 MAP, 184 Av. de Luminy, 13 288 Marseille Cedex 09, France

Keywords: Architectural Heritage, Knowledge Modelling, Visual Reasoning, Spatio-temporal Data.

Abstract: When studying heritage architecture, and trying to represent and understand the development of artefacts,

one should not only examine key moments in their evolution, but describe the whole process of their

transformation - thereby correlating contextual causes and architectural consequences. In this contribution,

we introduce a methodological framework of description of architectural changes, the corresponding visual

tools, and finally present elements of evaluation. The results we report show the description framework

favours information discovery: cross-examination of cases, analysis of causal relations, patterns of change,

etc.

1 INTRODUCTION

Historic artefacts are today widely regarded as

landmarks in our cities: physical landmarks as well

as symbolic ones. They act as tangible traces of a

broad, conceptual notion: time passing by, and the

metamorphosis of societies and cultures. And so

when wanting to actually analyse and understand

those artefacts, it is important to figure out that we

deal with history as well as with architecture.

Artefacts tell us how we became who we are, with

successive, wanted or unwanted, transformations

and influences. A scientist’s view over historic

artefacts thereby necessarily integrates

heterogeneous information sets with a strong

predominance of issues typically found in historical

sciences - uncertainties, incompleteness, long ranges

of time, unevenly distributed physical and temporal

stratification.

So the key point here is how can we better link

the objects we study, architectural artefacts, with the

information needed to understand their changes.

Let’s take a quick example: in 1367 a major fire

bursts out in the city of Krakow (Poland), spreads

from roof to roof and causes huge degradations. As a

consequence, a new law is adopted that states a high

wall should from then on separate each dwelling

from the neighbouring edifices so as to avoid “fast

fire propagation through roofs” (Fig. 1a).

As a consequence, the outlook of urban blocks

dramatically changes. Fire walls are built between

edifices, roof slopes are inverted – from outbound to

inbound - with a central gutter for rainwater (Fig 1b)

hidden by a high decorative wall along the street

called attic (Fig 1c).

With time passing by, the wiklerz 1367 rule is

abandoned, but the image of attics remains as a

cultural landmark. New edifices continue to be

designed with high attics although no constructive or

legal reason subsists. So how can we today explain

the presence of attics in Krakow’s cityscape, if not

by mentioning the notion of “fire”, if not by linking

architectural consequences with their historical

causes?

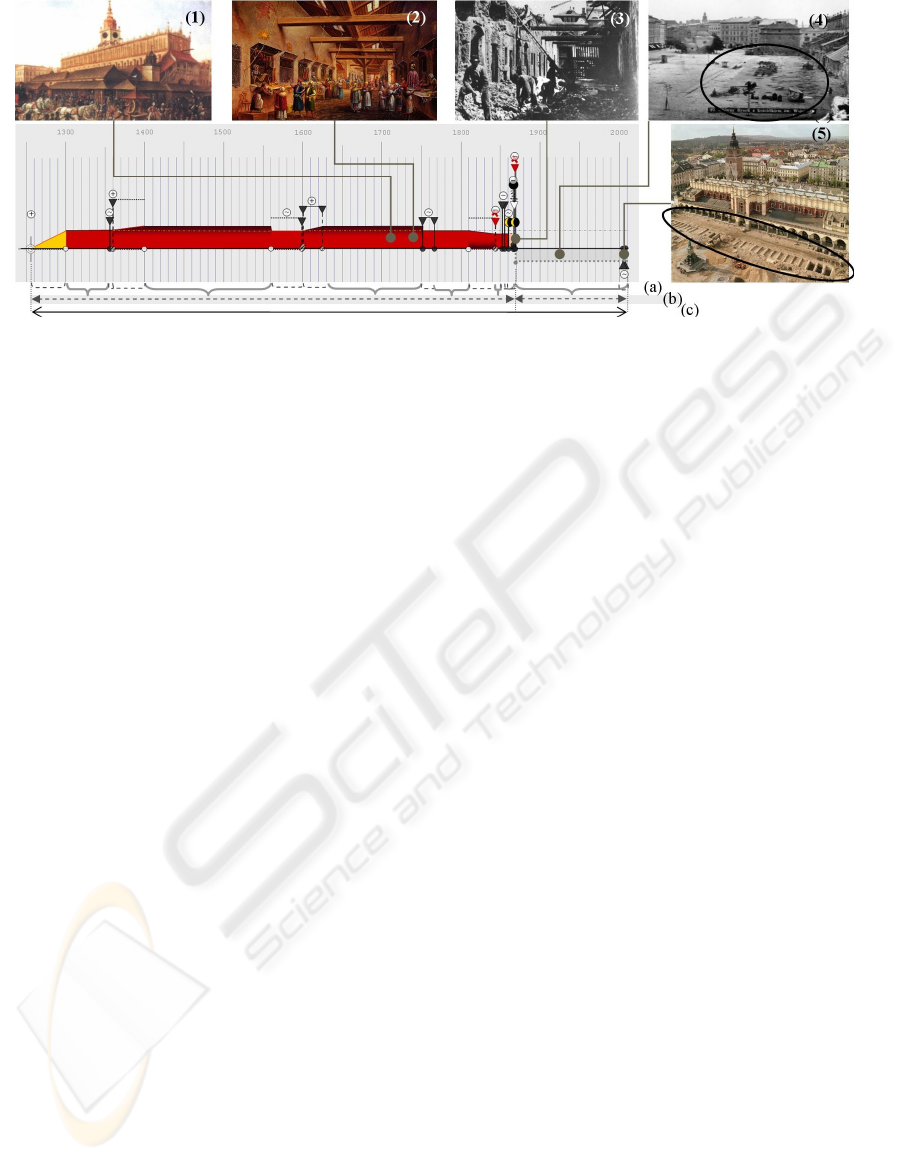

Figure 1: (a) a fire occurring in the first artefact spreads to

others through roofs. (b) new law promotes fire walls in

between dwellings (black) to prevent fires - roofs are

reversed with gutters (blue dot) in the middle of the

façade. (c) in order to hide the new fire roofs decorative

attics are built which remain until now (d).

The idea that artefacts are tangible education is

not new. XIXth century pioneer of architectural

conservation Viollet Le Duc wrote a famous book in

which he uses an imaginary city to recount the

evolution of rules and customs of urban societies

since the end of the Roman Empire.

He thereby underlines how the successive

transformations of artefacts are inherent

consequences of events, trends, facts – i.e. of a

91

Dudek I. and Blaise J. (2010).

UNDERSTANDING CHANGES IN HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE - Can We Provide Tools & Methods for Visual Reasoning?.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Imaging Theory and Applications and International Conference on Information Visualization Theory

and Applications, pages 91-100

DOI: 10.5220/0002826000910100

Copyright

c

SciTePress

context. The context does not necessarily explain the

architectural solution itself, (like in any art-related

practice) but it helps understanding what causes led

to wanting a new architectural solution.

Our contribution can be seen as an application of

Viollet Le Duc’s vision: we propose a

methodological framework aimed at identifying and

describing causes the consequences of which can be

read on the artefact itself. More precisely, the

lifetime of an artefact is considered as a continuous

chain along which two types of links alternate:

transitions (changes) and states (periods of stability).

In a previous contribution (Dudek and Blaise,

2008a), we introduced this research’s scientific

background, our early ideas on the description of

artefact changes. In this paper, we will first take a

broader but brief look on the scientific background,

and present key aspects of the description grid. We

will then detail how we completed the

methodological framework, its visual tools, and

finally present and discuss the evaluation procedure.

2 BACKGROUND AND

OBJECTIVE

Providing models to handle the dynamics of change

has been, and remains, a hot research topic in

geography or geospatial sciences. Applications

range for instance from the analysis of human

movements (Zhao, 2008) to the visualisation of

physical phenomena (Knopf, 2002). A set of

examples well-known to SVG developers is the

carto.net repository - with for example the classic

Choroplethe map “social patterns of Vienna” by

A.Neumann (Neumann 2005). However these

applications focus on the modelling of dynamics that

have little to do with the very nature of data sets

handled in historic sciences (uncertainties,

incompleteness, varying credibility of sources, etc.).

Furthermore, even when dealing with urban changes

- see for instance (Hagen-Zanker, 2008) - most

approaches use a systematic spatial clustering that

cannot be transferred (without losses in semantics)

to ill-defined architectural spaces. The issue we were

facing when starting this research resembles what

(Hagen-Zanker) identifies as the drawback of

“descriptive models [...] based on static situation”: a

weak understanding of processes and of causal

relations. As mentioned in (Dudek and Blaise,

2008a), little has specifically been done, in the field

of the architectural heritage, in order to describe and

represent visually the time-chain between successive

states or moments in the evolution of artefacts. A.

Renolen’s graphs (Renolen, 1997), where changes in

land areas are visually assessed through synthetic

diagrams, can however be quoted.

Renolen describes and represents territorial

changes: he isolates states and defines events

causing changes – notions that we do implement.

However, his field of application is land areas as

seen by a geographer, and the graphs proposed are

far from being applicable to architectural changes.

Nevertheless his point is a vital one : on one hand he

develops a theoretical model of a dynamic spatial

phenomenon, on the other hand he develops a visual

“language” using metaphors and/or formalisms used

in visualising temporal data (although in a rather

straightforward manner, notably without assessing

duration and intensities, as defined in (Sabol and

Scharl, 2008) or (Blaise and Dudek, 2008b).

Accordingly, our objective ultimately meets two

complementary issues:

describing architectural transformations (i.e. a

knowledge modelling issue),

reasoning visually about those changes on real

cases (i.e. an infovis issue).

Given a robust methodological framework, and

efficient diagrammatic representations as means to

visualise this framework, we expect graphics to help

amplify cognition (Kienreich, 2006) over artefact

changes by uncovering patterns of evolution within a

site or across sites, by underlining uncertainties or

exceptions (“documentary gaps”), by raising

questions about the relative evolution of families of

artefacts (urban houses in this or that quarter of the

city, churches across the city, etc.). In other words,

we intend to try and apply, in what we view as a

visual assessment of architectural changes, E.R

Tufte’s “first principle for the analysis and

presentation of data : show comparisons, contrasts,

differences” (Tufte, 2006).

3 THE DESCRIPTION GRID

We introduced in (Dudek and Blaise, 2008a) a

theoretical description identifying an artefact’s life

cycles as sums of states and transitions. Broadly

speaking, the description grid’s objective is to give

professionals the means to describe, date (with

uncertainty assessment), and order meaningful

events, facts, and elements of context (meaningful -

i.e. needed to understand the artefact’s changes).

This selection of events/facts/elements of context is

our a priori modelling bias (Francis, 1999), based

here on an intersubjective analyses of sources.

We sum up principles, findings and recent

developments of this first step in section 3, before

detailing in sections 4, 6, and 7 the framework’s

IVAPP 2010 - International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

92

Figure 2: Description grid illustrated on Kramy Bogate (rich stalls), an edifice demolished in the second half of the XIXth

century but with important remains (a whole storey in fact) under the level of the actual market square. Top, (1) to (5),

archival material documenting states and the demolition transition (3). Bottom, (a) states and transitions - (b) life cycles -

and (c) evolution.

completion, evaluation and analysis.

The description grid poses three principles:

Transitions ≠ states - Transitions identify

changes of the artefact - they act as causes. States

correspond to time slots during which no major

transformation occurs.

Evolution = ∑ (life cycles) – An artefact’s

evolution encloses all transitions and states

occurring during its lifetime. But an artefact may

be transformed to the extent that it only remains

as an underground, buried structure. Thus

transitions and states can be grouped into periods

of visible or of concealed existence that we call

life cycles. (Accordingly an artefact’s evolution

may contain several life cycles - think of

Pompeii, once a Roman city, then buried under

ashes, and now living a third life cycle as tourist

sites).

Artefact = ∑ (portions) – Divisibility of an

artefact when it is transformed (an artefact may

be subdivided into portions that live

autonomously).

The proposed description grid identifies seven

transitions and states occurring within a life cycle

(abandon, decay, annexation, demolition,

modification, secession and segmental anaesthesia);

as well as 8 transitions and states starting or ending a

life cycle (creation, extinction, hibernation,

internment, merge, reincarnation, split and

translocation). Tags used to denote these transitions

and states have been chosen as illustrative enough to

let the reader grab their semantics. However, tags

use ethnic languages, and thereby remain somehow

ambiguous, with possible misinterpretations of

notions like hibernation. Accordingly, each

transition / state is denoted by a tag, for

communication purposes, and also defined by non-

ambiguous properties that help the analysts choose

the one transition or state that best fits his needs.

We do not detail this aspect since this paper does

not focus on modelling problems but readers may

find an abstract of these definitions in (Dudek and

Blaise, 2008a). Let’s still give an example: we

define internment as the “Building of a new artefact

over a previous one, the latter remaining underneath

as an inactive, inaccessible portion called a segment,

Internment may be deliberate (ex. preventive

archaeological bury) or unintentional”. In that case

an artefact A is buried underneath a new,

independent artefact called B. Internment requires

that A becomes an inactive and inaccessible portion,

with no physical or functional continuity with B.

3.1 Reasoning Visually about Changes

Basing on the above framework, two linear

diagrammatic representations are proposed, called

diachrograms and variograms. They can be

combined with one another and displayed along with

a time scale that matches the artefact’s evolution.

Diachrograms present the evolution of an artefact

along a time axis. They are composed of a set of

visual indicators representing successive transitions

and states combined into life cycles. They rely on

the classic concept of timeline (Blaise and Dudek,

2008b), with markers that position transitions, states,

and causality assessments along the time scale. It has

to be said that a diachrogram represent an expert’s

view of the artefact: different analyses of the

information gathered on an artefact may lead experts

to propose different chronologies - the diachrogram

then acts as a comparative tool.

Variograms further detail the nature of the

artefact’s transformation by combining in a parallel

UNDERSTANDING CHANGES IN HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE - Can We Provide Tools & Methods for Visual

Reasoning?

93

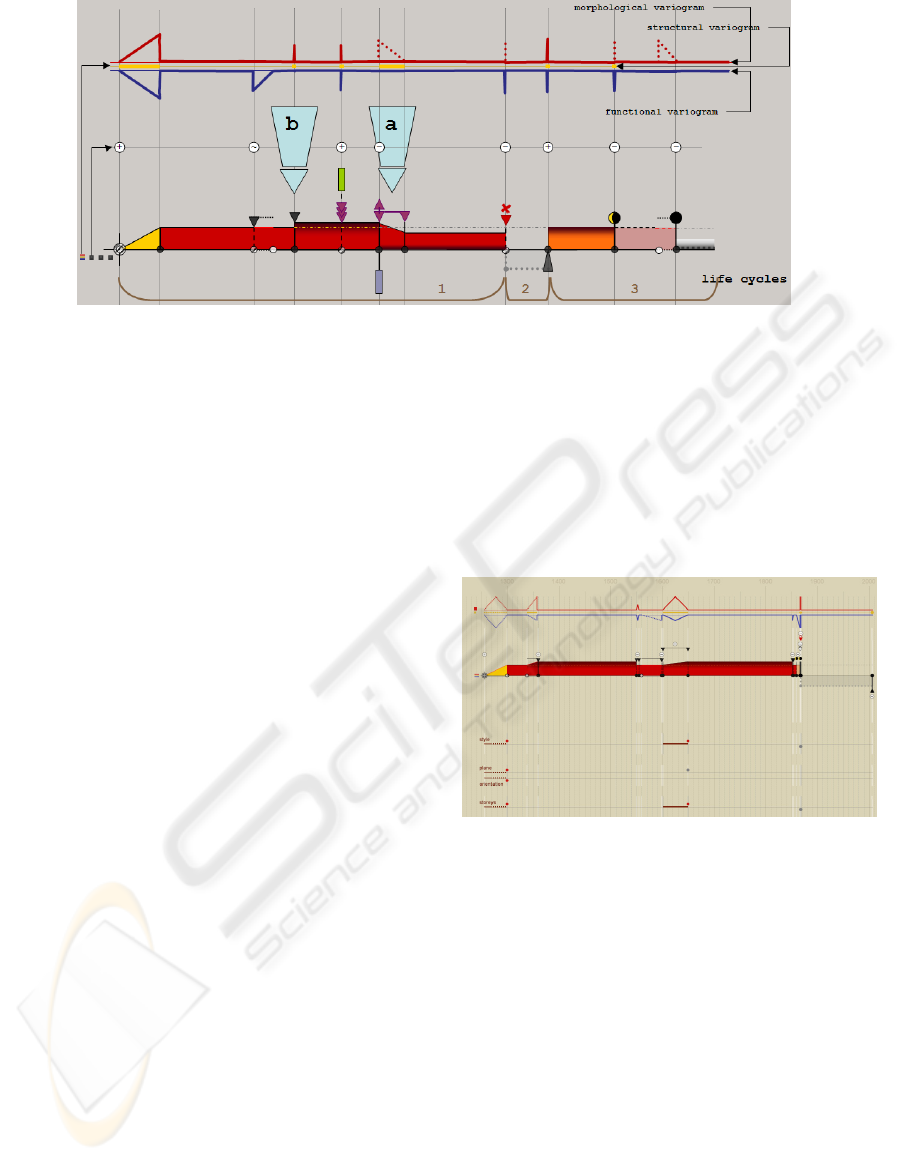

Figure 3: Top: variogram – movements and magnitude indicate periods of morphological, structural or functional changes

and their intensity. Bottom, diachrogram sums up visually life cycles, transitions and states. Beginnning and end of

transformations are marked by a circle (filling identifies certainty of the underlying information). Transformation types are

represented by symbols situated over the dating circles along a vertical line. (a) lasting transition – two dates needed to spot

the period of changes, (b) sudden transition – one date only.

visualisation three categories of changes:

morphological transformation (formal changes

such as stylistic refurbishing, decoration, or

changes in surface, volume),

structural changes (technical changes such as

change of roof material, replacement of sub-

elements such as floors),

functional changes (significant switches in use or

owners).

Variograms help underlining visually coinciding

changes, and stress possible links between these

three aspects. Durations (with their uncertainties) are

visualised, as well as intensity (Fig. 3).

4 VISUALISING CHANGES OF

INDIVIDUAL FEATURES

The evaluation of the variogram + diachrogram

disposal showed its efficiency in underlining and

ordering changes: the disposal gave a good global

vision on successive transition and states (see Dudek

and Blaise, 2008a). However it gave only a global

view: it showed for instance that “a fire occurs at

period p” but did not detail its actual consequences

on the various features of the artefact. We therefore

completed the description grid in order to allow the

visualisation of consequences events have on the

artefact’s individual features (change in size, in

style, in construction material, in owner).

For each category of changes a specific list of

features is proposed, with varying variable types.

For instance, the number of storeys can be given by

an Integer, whereas the stylistic changes require

lexical scales. Visualisation of each feature’s

chronology is combined with variograms and

diachrograms in a linear, timeline-like disposal. The

visual solution, inspired by E.R Tufte “data-ink ratio

principle” (Tufte, 2006), combines a limited number

of elements: lines, dots, colours (Fig. 4,5,6,7).

Figure 4: features chronology (bottom, partial view)

combined with diachrograms and variograms in the SVG

implementation of the framework.

Features we handle are represented by different

variable types. A consistent, easy to read,

visualisation features variations was therefore a

challenge (comparing visually increase in number of

storeys - an integer, and style - a closed lexical

scale,and with owners - an open lexical scale, may

lead to noisy effects such as over-emphasising a

feature because of the lexical scale’s size).

As an answer, we chose to produce for each

feature two different graphics, an activity indicator

that only says “this particular feature changes at

period p” and a feature readout that details the

change. On dynamic loading of the graphics only the

former is displayed. Selecting it commands the opening of

the second (see Fig. 5).

IVAPP 2010 - International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

94

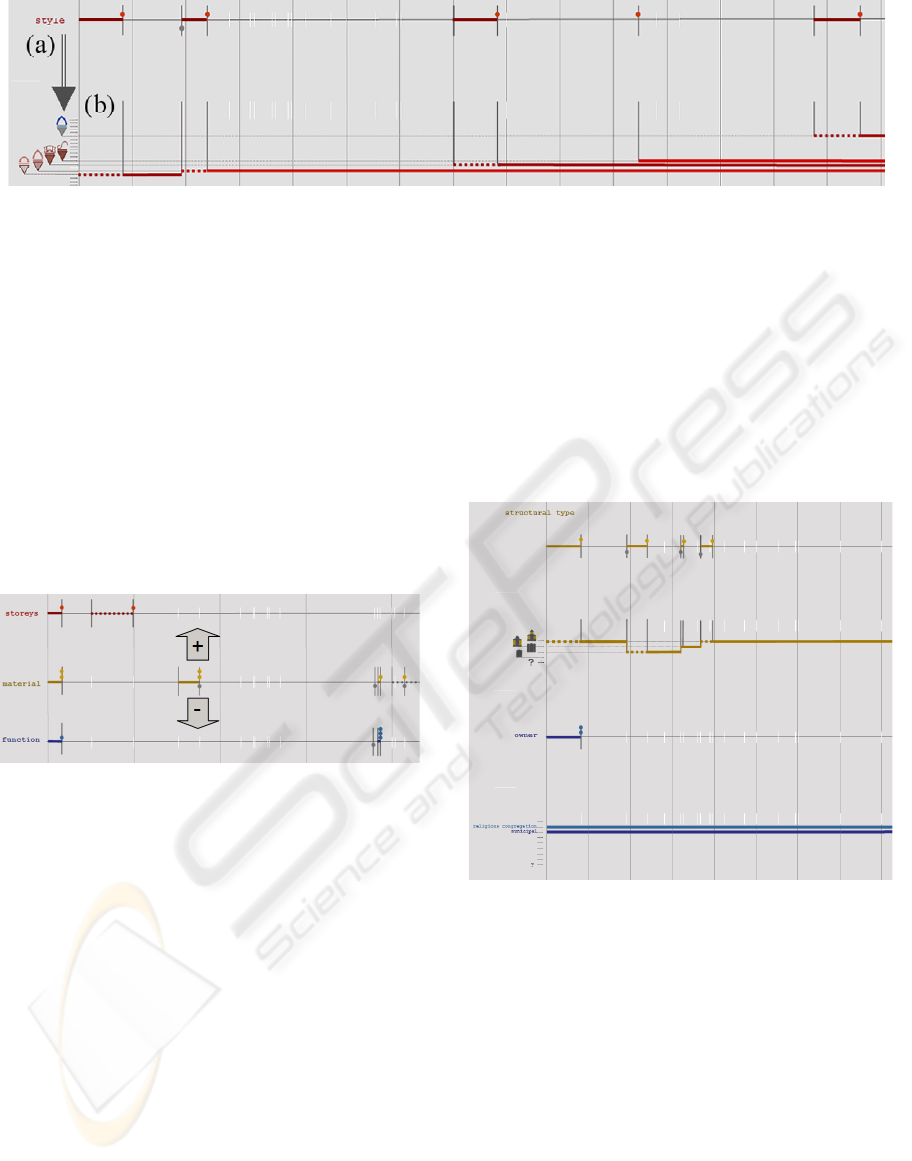

Figure 5: (a) - activity indicator for feature “style”– when selected by the user opens (b) - feature readout (here stylistic

affiliations represented by icons – Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and neoGothic elements successively appear

during the evolution of the artefact). Thick lines on the activity indicator identify periods when the feature appears. The

continuous lines in the feature readout indicate the feature persists in time (note here that the bottom line – Romanesque

stylistic affiliation – ends with the appearance of gothic elements, a visual indication that the initial structure is not

complemented but replaced).

The activity indicator is displayed first. Its role

is to position changes (with their intensity) along the

timeline, in the most “economic” way possible.

Since variation assessment is represented by an

integer, its visual marker can then be the same for

each feature. Colours indicate the category of

changes to which the properties correspond

(morphological, structural or functional), dots over

the timeline indicate additions and dots under the

timeline indicate losses.

Figure 6: activity indicator – examples for the three

categories of changes. Plus and minus signs indicate here

“’two materials added to the artefacts and one withdrawn”.

As can be noticed on this example, changes in material

reported here had no correlated consequences on number

of storeys or function.

Once an activity is reported by the above activity

indicator, more can be learnt on its nature from the

feature readout. It details the architectural

consequences of changes. Feature readouts have

visual markers that match the specificity of the

underlying variables and - although we tried to keep

a visual consistency by privileging simple lines -

their visual “weight” varies. Legend of the readouts

can use either icons or tags, depending on whether

the lexical scale is closed or not.

The full visualisation of the completed

description grid in definitive combines three tools

for reasoning - diachrograms and variograms that

allow a global view on changes, and features

visualisation disposals that foster comparisons

across features. The whole disposal is designed to

combine vertical readings - “what precisely happens

at period p” – and horizontal readings “ how does a

feature change with time” (Fig. 8). In that sense, the

disposal matches Bertin’s view of graphics as

“visual answer to a question” (Bertin , 1998).

Figure 7: Two feature readouts (example of a church): the

top one uses a list of icons corresponding to canonical

structural types for churches (hall, basilical, pseudo-

basilical), the bottom one a list of tags for the owners.

Note that if the artefact’s structural type does change with

time; its owner remains here the same – a typical pattern

for this family of artefacts.

5 IMPLEMENTATION

This development complements previous works on

the same test field - the medieval heart of Kraków -

presented for instance in (Blaise and Dudek, 2005)

or (Blaise and Dudek, 2007). Accordingly, the

technical platform is here the same:

a description of artefacts as instances of a hierar-

UNDERSTANDING CHANGES IN HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE - Can We Provide Tools & Methods for Visual

Reasoning?

95

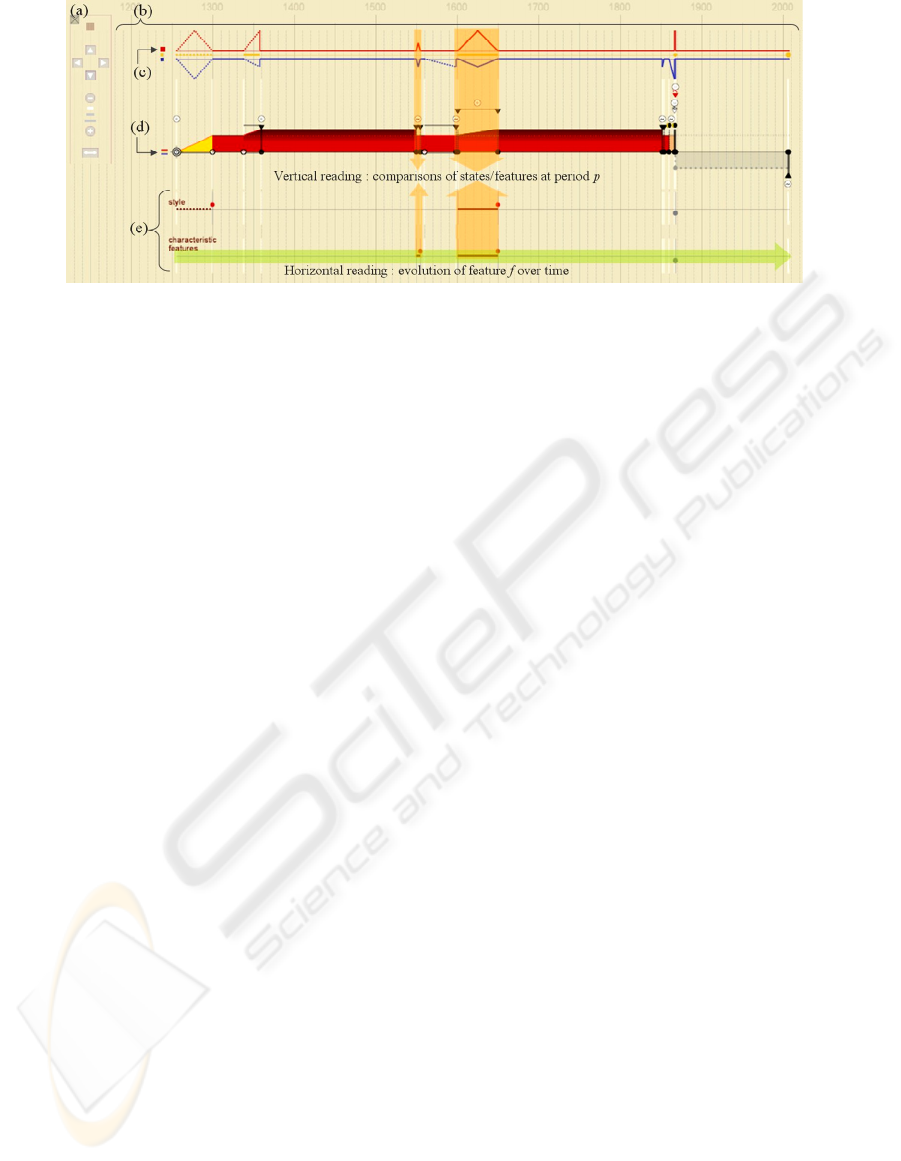

Figure 8: (a) Jscript nested interactive commands (zoom, pan, etc.), (b) time grid, (c) features visualisation open/close

buttons, (d) variogram open/close button (e) feature activity indicators (partial view) - SVG implementation of the

framework.

chy of classes (in the sense of OOP), with

persistence enabled through RDBMS structures,

outputs (may they be visual outputs – 3D VRML

or 2D SVG- or textual outputs –XML) produced

by Perl scripts,

interfaces produced by Perl scripts either as

XHTML (in our first experiments) or as

XML/XSLT datasheets,

Both the evolution of architectural and urban

elements (341 objects, 885 phases studied) and

historical sources used during the investigation (791

sources) have been described. Graphics are dynamic

SVG outputs (see Rathert, 2005). The whole system

is flexible to incremental data update.

6 EVALUATION

In a preliminary evaluation (Dudek and Blaise,

2008a), experts of architectural conservation

working on our field of experimentation considered

that the notions we introduce (i.e. the knowledge

modelling level) are relevant. Still their opinion

could be seen as biased on two aspects: they know

very well the artefacts we have described, and

moreover they know us … It was therefore

important, before trying to conclude on the possible

benefits of the methodological framework, to carry

out a more open evaluation. Is the whole disposal

workable for non-experts? Do non-experts learn

anything about an artefact when handling the

disposal? Do they learn more about how artefacts

change with time by the cross-examination of cases?

Unlike in (Dudek and Blaise, 2008a) where the

focus was put on knowledge modelling issues, we

here focused on understanding to which extent the

tools and method do help reasoning visually about

artefact changes. Accordingly, both the graphics and

the underlying semantics are concerned, with a

series of tests shortly described hereafter.

6.1 The Evaluation Procedure

The evaluation was carried out with two groups:

four students in mechanical engineering (no

background at all in architecture or architectural

conservation), and five students in digital

architecture (PhDs dealing with survey issues

mainly - background in architecture, art or civil

engineering but not in architectural conservation,

with two of them having a background as

archaeologists). The numbers of testers is extremely

limited, and the evaluation therefore does not claim

more than giving us hints on where to go next. The

groups also differ in cultural background (five

nations, from China to Morocco). We gave them a

45‘ introduction to the methodological framework.

We then proposed three successive series of tests:

Memorisation and Reproducibility Tests. We here

tried to evaluate with 14 questions “to which extent

the visual solution is readable” (weight of graphics,

efficiency of the colourisation, readability of the

transition/state successions, etc.). Diachrograms,

variograms and feature visualisation disposals were

projected on a screen for 30 seconds, and then

replaced by a specific question on the graphics’

content (“how many life cycles did you see”, “any

differences between blue and red line of the

variogram”, “redraw the profile of a diachrogram”).

Time was not counted.

Clarification Tests. The disposal uses visual

formalisms that may lead to possible ambiguities:

icons and multilayer feature readouts in particular.

In a short questionnaire (4 questions) groups were

asked to match either icons or sections of feature

readouts with pictures or schemas (see Fig. 9).

IVAPP 2010 - International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

96

Figure 9: Groups were asked to say which of the three

schemas on the left (1,2,3) does not correspond to section

of the storeys readout (marked here by green arrows).

Exactness, Efficiency and Discovery Tests. We

here tried to evaluate (20 questions) “to which extent

the disposal is workable”. This time each member of

the groups was given a complete real case example

presented as printed material. Questions were

projected on the screen that required testers to

actually read specific information on the graphics

with time counted.

The exactness test questions required only a

good understanding of the disposal, but no

interpretation capacities (questions like “longest

transition”, “number of transition types” are

straightforward once the mechanics of

horizontal/vertical reading is understood). The

efficiency tests required limited interpretation

capacities - properties needed to be cross-examined,

like “find consequences of event E” or “compare

number of changes of features plan and style”.

Finally, the discovery tests questions clearly stepped

out the reading of values and required analytical

reasoning over features and cases (“what relation

can you find between number of storeys and number

of functions?” or “point out and explain a non-

regular functional behaviour among cases”). For this

last test the groups were allowed to compare cases.

6.2 Analysis of the Outputs

Memorisation and Reproducibility Tests. We ana-

lysed the answers with regards to three criteria –

layering and separation (typically necessary to

distinguish transitions and states); reading of values

(such as dates or transition types), identification of

profile (global view on the artefact’s evolution). One

has to keep in mind that testers had to answer

questions using their visual memory. Results in

Table 1 show the percentage of testers who could

give answers.

Table 1: Percentage of testers who gave answers.

criterion 1

s

t

group 2

n

d

group

layering and separation 85,8 % 80,6%

reading of values 73,25 % 71,25%

Identification /

reproduction of profile

69,3% 81,3%

Considering the narrow number of testers,

significant differences between the two groups are

only visible on the last criterion. The first group

(mechanical engineers) shows weaker capacity to

identify and reproduce profiles of diachrograms and

variograms, and was not sensitive to differences in

the weight of graphics. This may be due to

differences in education: the second group practices

drawing on an every day basis. Both groups found

the test equally difficult, and declared a same level

of familiarity with memorisation tests. On the

overall, results show the visual solution is rather

easy to understand and memorise. The readability of

sequences (cause/consequences) is particularly eased

(“layering and separation” criterion) with over 80 %

of testers in both groups that become able to date,

order and reproduce from memory an artefact’s

transformations (new to them, naturally) after having

seen our visualisations on a screen for 30 seconds.

Clarification Tests. Surprisingly (when considering

they declared they know very little about the

architectural heritage), the group of mechanical

engineers has higher overall results (80% vs 61%)

notably on matching styles and their icons (81 % vs

45%), although the other group better identifies

styles on images (80% vs 62 %). It is possible that

this is because mechanical engineers had little

aprioristic knowledge on architectural heritage, and

therefore did not compare icons with previous

images they had.

It is important to also consider here the cultural

diversity of the group, which probably weakens the

tests. Inside each group, results of individuals vary

strongly. In conclusion, these clarification tests lead

to a rather consensual observation: when the

semantics behind graphics is strongly domain-

dependant, one can hardly escape from providing a

good legend.

Exactness, Efficiency and Discovery Tests. With

only three wrong answers out of 90, exactness tests

show that even with a rather short introduction to the

disposal, both groups could rapidly grab its logics.

However testers were asked to show their answers to

monitors before validating them, and so three wrong

answers means here “testers who never could find

the correct answer”.

Monitors counted retries, which average at 0.52

per person and question. The average value however

gives an unfair view: if taking the six best, average

is 0.18 per person and question. This shows some

testers had clearly more difficulties than others, a

problem that may be connected with fluency in

language, but that in all case would require more

investigation.

UNDERSTANDING CHANGES IN HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE - Can We Provide Tools & Methods for Visual

Reasoning?

97

Figure 10: (a) Two diachrograms projected for 30 seconds.

(b), (c) these diachrograms redrawn from memory by

testers (b least performing tester, c best performing one) –

the readability of sequences and their memorisation

appears quite convincing. Time slots are respected, the

nature and duration of changes as well, and in (c) the state

of hibernation of these two examples duly noticed.

In the efficiency tests we added a time

constraint. Results are this time of two wrong

answers out of 90, and the average retry rate falls to

0.26 – 0.11 for the six best. Under time constraint,

testers perform better, which seems to indicate that

although complex at start, the disposal has a fast

learning curve.

The two groups however performed differently

as far as time is concerned: whereas for the first

group answers required for 85 % between 1 and 2

minutes, only 18% of answers required more than 30

seconds in the second group. At this stage it is

reasonable to consider this as a bias in the

monitoring of the tests.

Finally, in the discovery test we allowed no retry.

Wrong answers (including “no answers”) remain at a

reasonable 9 % rate. Furthermore, in 73 % of cases

testers could uncover by themselves a causal relation

or a specific pattern ( topological relation of objects

by observing consequences of fires, horizontal

functional variogram for churches, etc..)

Figure 11: Observing resemblance of the three variograms

above, testers could uncover by themselves the functional

variogram pattern for churches.

7 BENEFITS & LIMITS

Benefits of the method, and here we mean of the

modelling bias itself, and of the visual tools

developed, can be shortly summed up:

Allows performing reasoning tasks on the

evolution of an artefact as a whole.

Allows performing reasoning tasks on feature

changes inside the artefact, and on relation they

may have to the evolution of the artefact as a

whole.

Allows comparing changes on an artefact to the

evolution of neighbouring ones (in space, in

history, in function).

Helps performing reasoning tasks on the

evolution of artefacts even when only qualitative

information are available on their morphology.

Allows non-ordered integration of new pieces of

information.

Does not imply a strong competence in computer

solutions.

Helps to uncover causal relations.

Fosters cross-examination of divergent interpre-

tations (and thereby discussions on how to

interpret historical evidence).

Figure 12: Top line, diachrogram for St Mary’s basilica

seen as a whole and underneath, diachrograms for each of

its sub-parts. Note, vertically, and underlined by a greyish

background under arrow a), how the neo-gothisation

change does not propagate in b) (the two already gothic

towers) and in c) (the baroque portal): artefact changes

must be read at different scales.

Helps underlining tendencies, patterns,

exceptions – in variations of individual features

IVAPP 2010 - International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

98

of artefacts, in variations of types of artefacts, in

variations of artefacts at a given time slot, or in a

given geographical area.

Uncovers lacking, inconsistent, contradictory

pieces of information.

Can be adapted to various spatial granularity.

What the artefact is, as a whole, is NOT the sum

of what its parts are, accordingly artefact changes

must be read at different scales, each of them

corresponding to alternative sets of information

(Fig12).

It is clear that a number of limits also need to be

quoted, starting with technical ones. Our

implementation is fundamentally a simple one. More

needs to be done in order to implement the context +

focus principle – at this stage basically a zoom+pan

solution. Comparison mechanisms, and switches

between spatial granularities also require further

developments.

But beyond these technical limits, it is important

to mention more fundamental issues, on which our

attention is today drawing:

The time granularity issue – Our unit at this stage

is a year, which is a rather thick granularity. But

the real problem is not to go down to a

granularity of for instance a day: the problem is

that the dating of historical events varies in

nature and in precision. The initial indication we

handle may for instance be “autumn of year

YY”, “first quarter of century CC”, or “morning

of day DD”. Two challenges are therefore

opened: on one hand developing a description

model that would help us give more precision

when possible, but that would also handle

fuzziness; and on the other hand finding a visual

solution that would remain consistent and yet

offer alternative encoding depending on the

nature of the initial indication.

The context assessment issue – performing

reasoning tasks about how artefact changes

implies cross-examining sets of possible causes

that would participate in the emergence of

architectural consequences. A certain number of

these causes have been identified and are already

visualised. But a number of patterns of evolution

are connected to the emergence of a more

general “context” – cultural influences, wanted

or unwanted presence of foreign powers for

instance (Fig. 13). This general context may help

underlining patterns, but it may also help

rethinking the initial data set, with for instance

the nomination of a new Bishop helping to date

with more precision changes on a church for

which we have poorly defined temporal

information.

In addition, the evaluation procedure we have

carried out is undoubtedly a limited one.

Accordingly, future works will focus on evaluating

the framework through more cases and granularity,

on developing better context + focus mechanisms,

and on time granularity / context assessment issues.

Figure 13: Context assessment helps decoding patterns –

vertical arrow a) corresponds to the Czech presence in

Cracow: a period of development of public edifices (four

bottom lines. Vertical arrow b) corresponds to the

Austrian occupation of southern Poland – a period of

massive extinction on the main square. In c), period

corresponding to a German presence in Poland, a portion

of the town hall’s unused underground structures

(segmental anaesthesia – visible on the diachrogram under

the time axis) is destroyed in order to build an

underground cistern.

8 CONCLUSIONS

Observing that solutions lack when one wants to

recount and sum up the evolution of historic

artefacts (lacks in terms of method of description as

well as of visualisation), we propose and apply a

methodological framework dedicated at a diachronic

reading of architectural changes. The framework

meets two principles for the analysis and

presentation of data quoted by (Tufte, 2006): show

causality, mechanism, explanation, systematic

structure and integrate evidence. The evaluation,

although limited, does provide useful indications:

The framework is usable by non-specialists, with

a fast learning curve,

UNDERSTANDING CHANGES IN HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE - Can We Provide Tools & Methods for Visual

Reasoning?

99

It allows information uncovering and delivers

domain-specific notions (uncertainty for

instance).

It will however be necessary to try out the

framework at other scales before concluding on its

possible extension. Beyond limits reported in section

7, the framework also has more general limits,

inherent to the modelling choices made:

Requires a good analysis of the artefacts before

making any sense, implies to thoroughly describe

the evidence (including by uncertainty

“measurement”) and therefore is of little support

in the early phases of investigations.

Assesses causal relations, it orders in time

sequences, events, consequences, but it only does

that. The disposal is a one-dimensional narrative

disposal: it does not replace spatially and

dimensionally determined disposals, as

mentioned in (Dudek and Blaise, 2008) and

experimented in years (see for instance Blaise,

and Dudek, 2007). Our contribution should not

be seen as an end, but “yet another mean to

perform reasoning tasks” about a data set.

Given these precautions, the results we report

show that visual thinking can fruitfully apply to the

assessment of architectural changes. They also

underline an ongoing research issue in most

historical sciences: the necessity to better combine

space-oriented visual disposals (cartography, 3D

models, etc.) and time-oriented graphics (timelines,

ribbon maps, etc.).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank W. Komorowski and T.

Węcławowicz for their feedback and suggestions.

REFERENCES

Bertin, J., 1967-98 Sémiologie graphique; Editions

EHESS, Paris, 2

nd

edition.

Blaise J.Y., Dudek I., 2005. From artefact representation

to information visualisation: genesis of informative

modelling. In SmartGraphics International

Conference, LNCS Volume 3638/2005.

Dudek I., Blaise J.Y., 2007. Visual tools decipher historic

artefacts documentation, In I-KNOW 07, 7

th

International Conference on Knowledge Management,

JUCS (Journal of Universal Computer Science).

Dudek I., Blaise J.Y., 2008a. Visual assessment of

heritage architecture life cycles. In I-KNOW 08, 8

th

International Conference on Knowledge Management,

JUCS (Journal of Universal Computer Science).

Blaise J.Y., Dudek, I., 2008b. Experimenting timelines for

artefacts analysis: from time distribution to

information visualisation. In VSMM 2008, 14

th

International Conference on Virtual Systems and

Multimedia, Digital Heritage, Archeolingua.

Francis, S., 1999. The importance of being abstract. In

ECAADE 1999 Liverpool UK.

Hagen-Zanker, A., 2008. Visualization and classification

of urban change patterns on the basis of state-space

transitions. In 11th International Conference on

Geographic Information Science (AGILE-2008),

ttp://geoanalytics.net/geovis08/a17.pdf.

Kienreich, W., 2006. Information and Knowledge

Visualisation: an oblique view. In MIA Journal Vol0

Numb.1.

Knopf, G.K et al., 2002. Representing high-dimensional

data sets as closed surfaces. In Information

visualization Volume 1 N° 2, Palgrave.

Neumann., A., 2005. Vienna - Social patterns and

structures. From carto.net repository

http://www.carto.net/papers/svg/samples/wien.shtml

(accessed 03 09).

Rathert, N.A., 2005. Knowledge visualisation using

dynamic SVG Charts, In Geroimenko, V., Chen C

(Eds).: Visualizing information using SVG and X3D

Springer.

Renolen, A., 1997. Conceptual modelling and

spatiotemporal information systems : how to model

the real world. In ScanGIS 97.

Sabol, V., Scharl, A., 2008. Visualizing Temporal-

Semantic Relations in Dynamic Information

Landscapes. In 11th International Conference on

Geographic Information Science (AGILE-2008),

Semantic Web Meets Geospatial Applications

Workshop.

Tufte, E.R., 1990-2001. Envisioning information.

Graphics Press, Cheshire.

Tufte, E.R., 2006. Beautiful evidence, Graphics Press,

Cheshire.

Viollet Le Duc, 1878/1978. Histoire d’un hôtel de ville et

d’une cathédrale. Mardaga, Bruxelles.

Zhao, J. et al., 2008. Activities, ringmaps and

geovisualization of large human movement fields. In

Information visualization Volume 7 N°3, Palgrave.

IVAPP 2010 - International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications

100