A MULTISENSORY MULTIMEDIA MODEL TO SUPPORT

DYSLEXIC CHILDREN IN LEARNING

Manjit Singh Sidhu and Eze Manzura

Dept. of Graphics and Multimedia, College of IT, University Tenaga Nasional, Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia

Keywords: Multimedia, Dyslexic, Multisensory, Education.

Abstract: Multimedia has benefited many areas in education and users including disable ones. In this paper we

proposed a new courseware development model specifically for dyslexic children. The model could be used

for developing courwares for dyslexic children. Five essential features are identified to support this model

namely interaction, activities, background colour customization, directional for text reading (left-right)

identification and detail instructions. A prototype courseware was developed and tested with a small sample

size of dyslexic children (selected schools in Malaysia) based on the proposed model. The evaluation

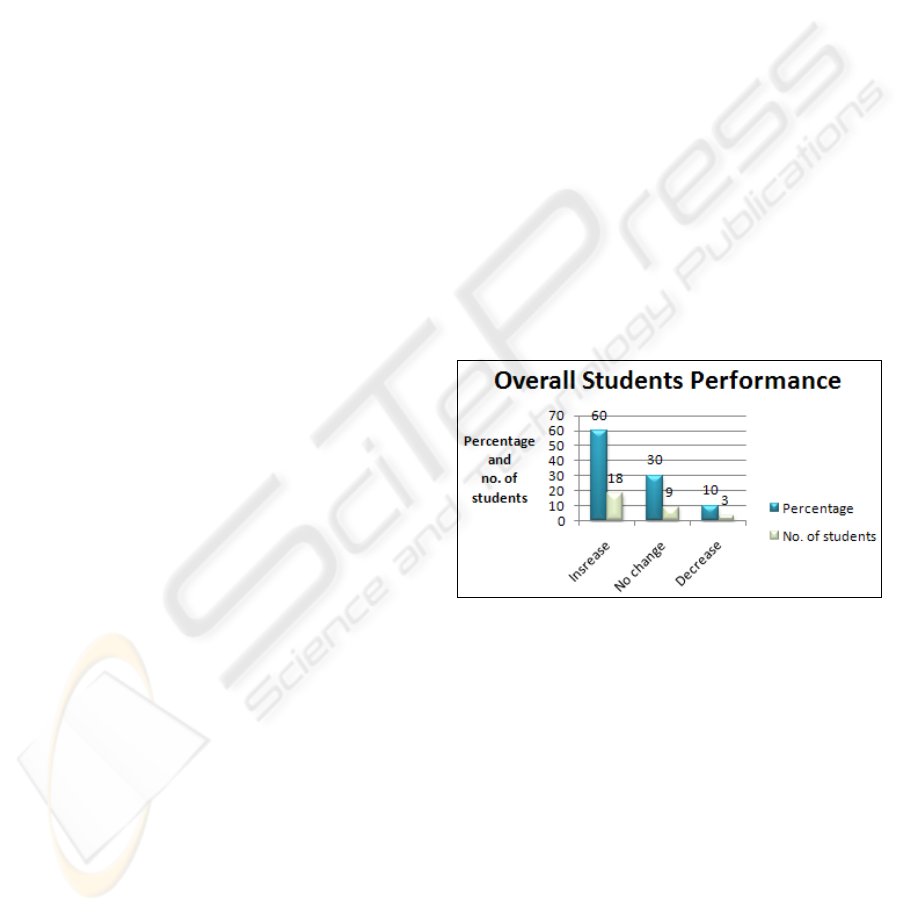

showed positive results in terms of performance whereby 60% of the users showed better improvement in

their performance, 30% unchanged result and 10% with decrement in performance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dyslexia is associated with difficulty or problem

with words specifically in reading, spelling and

expressing thoughts on paper (Greene, 2006).

Dyslexic children are physically and mentally

normal but have unusual difficulties in reading,

spelling and writing. According to a local press the

New Straits Times (2009), it is estimated about 5%

of school going children in Malaysia are dyslexic.

The word dyslexia is derived from the Greek

word “dys” meaning poor or inadequate and “lexis”

means words or language (British Dyslexia

Association, 2008). Along with the difficulties

mentioned above, dyslexia also affects memory,

concentration, sometimes mathematics, music and

self-organization (Hornsby, 1995). According to

some psychologists dyslexia is not a disease (Vicari

et al, 2005; Shaywitz, 2003; Berninger et al., 2008).

This is supported by Sariah Amirin (The Berita

Harian Press, 2009), the President of Dyslexia

Association, Malaysia in the quotation below:

“Dyslexia is not a disease it occurs in

children with normal vision and nothing to

do with the hearing, sight and brain

damage. It happens because the brain lacks

of a function to translate the image seen or

heard into something meaningful.”

Recently, there have been a number of

researchers looking at the benefits of multimedia

educational courseware and addressing various

educational issues in the market. This indicates that

multimedia applications are widely used within the

educational domain. Among others, the use of

multimedia as secondary learning tool could play an

important role to motivate students’ interest hence

improving their performance in learning.

The main objective of this research was to study

the problems faced by dyslexic children and to

evaluate the effectiveness of using multimedia

application as an alternative solution in order to

overcome the problems faced by them.

2 CURRENT STATE OF

EDUCATION FOR DYSLEXIC

CHILDREN IN MALAYSIA

In Malaysia, the dyslexia program was initiated by

the Education Ministry in 2004 where “Sekolah

Kebangsaan Taman Tun Dr. Ismail” was the first

school. At present, it is estimated around 5% or

314,000 of school going children in Malaysia are

dyslexic (New Straits Times, 2009). Even though the

figure is fairly high, the number of schools and

trained personnel addressing the problems are

relatively small; there are only about 30 schools that

193

Singh Sidhu M. and Manzura E. (2010).

A MULTISENSORY MULTIMEDIA MODEL TO SUPPORT DYSLEXIC CHILDREN IN LEARNING.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing and Multimedia Applications, pages 193-202

DOI: 10.5220/0002885901930202

Copyright

c

SciTePress

offer special programs for the dyslexic and 100

trained teachers in this field (Devaraj & Roslan,

2006; New Straits Times, 2009). Moreover, due to

the lack of knowledge, dyslexic children are left

behind and often misjudged as being lazy and slow

learners (low ability children with low IQ).

Based on the above-mentioned limitations,

a study was conducted on the problems faced by

dyslexic children and also the awareness level of this

problem in Malaysia. Based on the results gathered

from readings (journals and articles) and also

interviews (Dyslexic program teachers), it can be

concluded that Malaysia still lacks materials and

experts in the field (Lee, 2008; Devaraj and Roslan,

2006; Gomez, 2004). In a recent work, the causes

and symptoms of dyslexia have been defined

(Eze, 2010).

2.1 Problems Faced by Dyslexic

Children

Dyslexia as mentioned earlier is a specific learning

disability that leads to certain difficulties in the

child’s learning process. It is important for the

people around them (parents, teacher, siblings and

friends) to understand their problems so that they

can get the necessary help. Among those difficulties

as noted by Gross and Voegeli (2007) include:

difficulties in forming associations between letters

and sounds; remembering sequences of letters for

spelling; difficulties in recognizing or confusion

between letters or familiar words;

mispronunciations; difficulty in carrying out

instructions; directional confusion between left and

right; math activities; problems with sequencing;

difficulty organizing work.

All the above-mentioned difficulties have an

impact on the children’s ability to read, write,

navigate, comprehend and recall relevant

information (Rainger, 2003). On the other hand, the

difficulty with visual processing leads to the

problems of delay in visual object recognition and

problems with visual concentration and over

sensitive to light (Rainger, 2003). Additionally,

dyslexic children sometimes see words juggle in a

paragraph or rivers of white space. This problem is

referred to as a scotopic sensitivity (visual

perceptual disorder that affects primarily reading

and writing activities) or also known as Meares Irlen

syndrome (Irlen, 1991) where they might find that

the high contrast is difficult to read, for example

black text on white background (Rainger, 2003).

Besides that, they also have problems called Mirror

opposites or reversal of word and letter (Heymans,

2007). For example, they see letter “p” instead of

letter “q” and the word “saw” instead of the word

“was”.

2.2 The Courseware

The courseware developed for this research is based

on teaching and pronouncing words using the

national language (Bahasa Melayu / Malay

language) and targeted for beginners aged between

5 – 12 years old (teachers and parents may also use

as an additional teaching aid). The courseware

covers the following modules:

• Bahasa Melayu reading for beginners.

• Uses the eclectic-Express reading approach

(e-Xra) a technique that combines the two reading

methods that are phonics and whole word method

(as such we used the reading method i.e. one of

the phonetic reading for Bahasa Melayu).

• 12 syllables that are divided into 6 modules i.e.

module 1: ‘a’ and ‘ba’, module 2: ‘ca’ and ‘da’,

module 3: ‘fa’ and ‘ga’, module 4: ‘ha’ and ‘ja’,

module 5: ‘ka’ and ‘la’, module 6: ‘na’ and ‘ma’.

• Each sub-module is supported with audio and

visual elements as well as hands on practice.

2.3 Learning Styles

In this research we also took into account the

learning styles of the children. Learning styles is

defined as individual’s preferences of acquiring and

using information when learning (Herod, 2002).

Thus the definition shows that different individual

has different learning style. There are three basic

types of learning styles that are very simple and

suitable for children namely visual, auditory, and

kinesthetic (Beatrice, 1994). However each

individual can have more than one learning styles or

preferences because most people learn through a

mixture of all three styles (James, 2009). It is very

important for teachers to deliver their teaching with

the combinations of these three learning styles to

accommodate different learning styles of each

student. This is supported by Reid (2005) where he

suggested that when students are taught using

techniques consistent with their learning styles, they

will learn more easily and efficiently.

Visual learners learn best using images, pictures,

colors, and maps. They can easily visualize objects

(Douglass, 2008). In addition, visual learners prefer

to write things down and they have to see to be able

to understand better. They like to imagine the

information given. This will make them process and

understand information better (Tannahill , 2009). On

SIGMAP 2010 - International Conference on Signal Processing and Multimedia Applications

194

the other hand, auditory learner would prefer to

listen for information. They usually enjoy talking,

talk and read aloud and like explaining things to

others (The Penn State York Nittany Success Center,

2009). Apart from that, they are easily distracted by

background noise and having difficulties following

written instruction (Hutton, 2009). In contrast,

kinesthetic learner is basically a student who learns

most effectively from movement-based or motion-

oriented activities. They love to do hands on tasks,

physical activities and motor skills (Fleming,

2009). Further discussion is given by Manjit (2007)

on learning styles.

It is very important to identify students learning

style in order to accommodate the right teaching

method to enhance their learning performance

(Silver et al., 2000; Cutter, 2009). The learning

styles can be identified through observation or by

answering few questions related to learning styles

(Reid, 1987). There are many questionnaires

designed to identify children’s learning styles such

as:

• Accelerated Learning by Dr. Colin Rose

(Grammatis, 1998).

• Memletics learning styles inventory

(Advanogy.com).

• A Learning Style Survey for College by

Catherine Jester (Jester, 2000)

• Learning style inventory by Jonelle A. Beatrice.

(Union University, 2009).

For this research, we selected the questionnaire

“Learning styles inventory” designed by Jonelle

Beatrice (Union University, 2009) as the questions

provided are simple, straight forward and easy for

the lower primary school students (standard one to

standard 3) to understand.

2.4 The Teaching Technique

The suggested technique to teach dyslexic is by

applying the multisensory method in teaching

(Learning Disabilities Association America, 1998).

This method is proven to be effective method to

teach dyslexic children because it can accommodate

different learning styles (Logsdon, 2008). It is used

in many Special Needs schools and Dyslexia

centers, for example Dyslexia Association

Singapore, British Dyslexic Association, etc.

Research by the National Institute of Child Health

and Human Development (NICHD) reported that,

dyslexic children who were trained in multisensory

intervention program made significant achievement

in their learning skills (International Dyslexia

Association, 2000).

Multisensory teaching involves a simultaneous

links between visual, auditory and kinaesthetic-

tactile pathways to enhance learning and memory

(Marcia, 1998; Logsdon, 2008). In this technique,

children are taught to link the sounds of the letters

with the written symbol. They also have to link the

sound and symbol with how it feels to form the

letter/letters by tracing, copying or writing the letter

while saying the corresponding sound. Further

guidelines of what should be taught in multisensory

method can be found in Dyslexia Association

Singapore (2006) and Cecilia (2004).

2.5 The Malay Language Reading

Method

The first method of teaching beginners or children to

read Malay language is by using the alphabet

method (‘kaedah abjad / alphabet method’ or

‘mengeja / read’). In this method, children have to

spell out the letter names of segmented syllables

followed by sounding out the syllables then blending

up the syllables to form words. For example to read

the word ‘bola’ (which means ball), children have to

say the letter name of the first syllable (b + o) and

sound out as ‘bo’ and followed with the second

syllable (l + a) sound out as ‘la’. Finally they will

combine the sounds of those two syllables as ‘bola’

(Elias, 1998). To be able to use this method, children

have to remember the name of all letters and the

sound of combined letters. However it will take

much longer duration for children to read fluently

(Ahmad, 2004). Figure 1 illustrates the step by step

process in reading using the Alphabet Method.

Figure 1: Reading strategy using the alphabet method.

The second method is the whole word or sight

word method. This method is similar to the look and

sees method. In this method, children will be

introduced to meaningful words using flashcards

with picture and associated word representing the

picture.

A MULTISENSORY MULTIMEDIA MODEL TO SUPPORT DYSLEXIC CHILDREN IN LEARNING

195

The third method is the phonics method. This

method concentrates on the sound of letter and

sound of combined letters. Recently, the use of

phonics approach has been increasing especially in

pre-school. It shows significant improvement in

reading ability not only of the normal children but

also of dyslexic children (Ahmad, 2004). Due to its

benefit for dyslexic children as reported by

Hollowell (2009), Blevins (2003) and Ahmad

(2004), the phonics method was selected to be the

reading method in this research. Figure 2 shows the

steps in teaching Bahasa Melayu reading using

phonics method.

Figure 2: Phonic method in teaching Bahasa Melayu /

Malay language reading.

2.6 Dyslexia and Multimedia

With the problems faced by dyslexic children as

stated earlier, it is clear that dyslexic children need

additional aids as compared to normal children

(Shaywitz, 2005). In addition to the traditional super

visionary learning environment, dyslexic children

should be given the opportunity to explore reading

on their own, as it is indeed a good way to improve

their reading skills (Devaraju et al., 2006). Adopting

a computer aided learning (CAL) environment

would be an alternative as it could give flexibility to

the dyslexic children in terms of what to study and

when to study. Multimedia as mentioned by

Singleton (2006) is one of the aids to promote a

CAL environment since it has the potential to reduce

most of the problems faced by dyslexic children. For

example, Beacham (2007) in his article has

mentioned that learning materials containing text

can be supplemented with graphical and auditory

forms as dyslexic children are able to comprehend

meaning better in that format.

Multimedia has the potential to improve reading

ability as it provides large amounts of practice that

promotes the drill and practice concepts (Lundberg,

1992.). This is supported by Karsh (1992) in his

report where substantial gains were made by

dyslexic children in word reading fluency using

‘Construct a Word’ program. This program provided

drill and practice in forming real words by matching

consonants with word endings.

Lundberg (1992) in his research noted that

students who enjoyed the benefits of computer

training with speech feedback gained more in

reading and spelling performance compared to

students who had access to conventional special

education.

Singleton (2006) reported five principle

advantages of computer assisted instruction for

dyslexic children as following:

• Increase motivational value

• Individualized instruction

• Informative feedback

• Promotes active learning environment.

• Customization feature

With all the benefits stated above, multimedia

has opened up a completely new world to dyslexic

students, one that could help them in their learning

process.

Multimedia presentation techniques do have a

potential in providing outstanding support for

dyslexic children (Heymans, 2007).

Based on the details discussed earlier, a

courseware was developed to assist dyslexic

children in reading Bahasa Melayu. The method of

teaching that was integrated into the courseware is

the multisensory method as it has been

recommended as the best method to teach dyslexic

children (International Dyslexia Association, 2000;

Marcia, 2000) at present. Besides the multisensory

method, the phonetics method was also used as a

reading technique in this research.

The courseware developed was tested to evaluate

its effectiveness as well as to identify the best

features or elements that should be incorporated into

the courseware to ensure that it will give full benefit

to dyslexic children. As a result a new courseware

development model especially for dyslexic children

was proposed. This is discussed in the next section.

3 DYSLEXIA COURSEWARE

DEVELOPMENT

This section briefly describes the courseware

developed to help dyslexic children in their learning.

The multisensory method as discussed earlier

suggests that the subject or course to be divided or

structured into modules and the organization of the

materials should follow the logical order of

SIGMAP 2010 - International Conference on Signal Processing and Multimedia Applications

196

language. The content structure was based on these

guidelines. The content covers twelve sub modules

selected from a book (see sample content structure

in Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Content structure of the courseware.

Each of the sub modules contains five pages

where the first two pages introduce the user to the

new syllable together with the previous syllables. As

an example, in sub module ‘ba’, the first two pages

will show the ‘ba’ syllable with the associate sound

of ‘ba’ together with the previous syllable (‘a’) that

has been introduced before. The ‘ba’ (new syllable)

is represented in blue colored text while the previous

syllable (‘a’) is represented in black colored text.

The third page shows the word or sentence that can

be made by combining the current syllable (‘ba’)

and syllables from previous sub modules. The forth

page is where the student can see the associated

pictures of animals, things or people where the first

syllable starts with the current syllable (‘ba’) for

example ‘basikal’ (bicycle). The associated picture

with sound is to help children remember the sound

of the syllable better. The last page is where the user

can practice writing the letters using the mouse. This

gives the user the feeling of how to write the letter

and further on, easier for them to remember the

letters.

For ease of interaction with all the modules, the

courseware is equipped with a menu that allows the

user to access any module that they want. Based on

the structure of the content as shown in Figure 3, the

navigational structure for the courseware was

designed. The navigational structure summarizes the

overall flow of the courseware. There are several

navigational structures such as linear, hierarchical,

non-linear and composite (Vaughan, 1996). The

navigational structure for this courseware is based

on the composite structure that combines the three

navigational structures that are linear, hierarchical

and non-linear structure. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate

the navigational structure for this courseware.

Figure 4: Courseware navigational structure.

From the main menu, the user can choose any

module(s) that they wish to explore. Figure 4 shows

the courseware navigational structure where from

the main menu, the user can click on any of the

module(s) button, i.e. the help button or the exit

button to exit from the courseware.

The navigational structure within each module as

illustrated in Figure 5 was designed to give

flexibility to the user in exploring the content and at

the same time bonded to certain limitation or

constraint. The limitation or constraint was that the

user had to wait till the whole contents of each page

were presented before the user could navigate to the

next page, previous page or repeating the same page.

The implementation of this concept was targeted to

force user to finish the module without clicking

unnecessary icons and be lost in the modules. In

addition, the user could also try to read the content

of each page their self. In a condition where they are

not sure with the sound associated with the syllable,

they can click on the syllable to listen to its

pronunciation. This feature is available once the

whole contents of the current page had been

displayed.

On the last page of each sub module, the user can

click on the pencil icon which directs them to the

page where they can practice writing up the

letters/syllable while watching the animation on how

to write those letters/syllable. Once they had

finished this module, they can go back to the current

sub modules and later advance to the next sub

modules or go back to main menu to choose other

module.

A MULTISENSORY MULTIMEDIA MODEL TO SUPPORT DYSLEXIC CHILDREN IN LEARNING

197

Figure 5: Navigation within module.

Careful consideration was also taken in

designing the user interface design. We considered

the following six principles in designing the user

interface design: 1. Sufficient contrast between

foreground and background; 2. User control button

or navigation; 3. Provide sufficient white space so

that the information can be absorbed properly

(Hutton, 2009); 4. Fonts should be easy to read and

have clear spacing between letters; 5. Avoid using

blinking or moving text as this is hard for dyslexic

user to read and it will distract them; 6. Provide the

audio feature (narration) as this will help dyslexic

user.

The interface design for this courseware can be

divided into: Main page, Help page, Content/module

page and Writing Page. The main page was design

as simple and straight forward as possible

appropriate with its function as the first page of the

courseware. The page acts as an interactive table of

content or index page for the courseware. It has

menu buttons that will direct user to the modules in

the courseware. “Lady Bugs” were chosen as the

icons for the modules. The use of these icons was to

attract the user and make the page livelier. When the

user moves the mouse over the button, the ‘lady

bugs’ will stretch its wings. Tool tips are provided

for all the buttons together with the narration when

the mouse is moved over the button. This will help

dyslexic children understand the use of buttons

better. In total, there are six ‘lady bugs’ in this

courseware. Each ‘lady bug’ represents two sub

modules. Figure 6 shows the screen snap for main

menu.

Figure 6: Screen snap for the main menu.

As mentioned earlier, the content of this

courseware was adopted from the e-Xra technique.

With reference to the e-Xra book, we divided each

syllable as a sub module for example ‘a’, ‘ba’, ‘ca’

and others. Each module contains a combination of

two sub modules. All the sub-modules have the

same design in terms of the arrangement of

buttons/icons, colors and layout. This was to avoid

confusion and aligned with the interface design’s

principal that suggested a consistent design. Also

mentioned earlier, there is a directional confusion

among dyslexic children. The conventional way of

solving the directional confusion was by wearing a

bracelet on the left hand so the children will

remember that the hand with bracelet is the left hand

(Dyslexia Association of Scotland, 2008). In order to

cater this problem, the courseware is also equipped

with a left marker throughout the content page as

shown in Figure 7 label (a).

Figure 7: Screen snap for content page for sub-module ‘a’.

The left marker is represented using the hand

image which is located at the upper left corner of the

page. The use of the left marker is to assist dyslexic

children on identifying the left side of the page as

they always confused between left and right and

sometimes ends up reading from the right (Gross &

Voegeli, 2007). Besides the use of the marker,

another method was applied to help dyslexic

SIGMAP 2010 - International Conference on Signal Processing and Multimedia Applications

198

children to overcome the directional confusion. The

method was implemented by showing the syllables

one by one from left on the screen. This means, at

the beginning of each content page, the letters or

syllables will be displayed one by one from left to

right. The process will continue on each new page.

This will indirectly help dyslexic children to read

from left. All screen for the alphabets have the same

design and layout. On the upper right corner of each

content page, the page number for example page 1

out of 4 pages as illustrated in Figure 7 label (b).

Page numbers will help user keep tracks of his/her

visited page.

Additionally, the courseware also offers a

background customization feature that will give

flexibility for the dyslexic children to choose the

background color that best suited them. The choices

of colors are represented with a color palette on the

top left corner of the courseware as shown in Figure

7 label (c). The main intention of this feature was to

lessen the scotopic sensitivity or Meares-Irlen

syndrome.

Besides the text and icons that represent the

visual features of the courseware, the courseware

was also equipped with pictures to support the

learning process. These pictures were used to signify

the syllables. Example is the use of “chicken

picture” that symbolizes the syllable ‘a’ in the Malay

language as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Screen snap for content page for sub-module ‘a’.

On top of the visual layout of the content, the

courseware also offers the audio feature in term of

narration or the sound of each syllable. The sound of

syllable can be heard when the syllable appears on

the screen. The feature is tally with the multisensory

guidelines that has been discussed earlier. Moreover,

the user can also click on the syllable if they are not

sure of the sound. This can only be done when the

whole content of the current page has appeared. This

facility is hoped to help dyslexic children remember

the sound associated with each syllable better.

At the end of each sub module, the courseware is

equipped with the pencil button that will direct the

user to the writing page. The button is shown in

Figure 8 label (a) while Figure 9 shows the writing

page. This page is to compliment the kinaesthetic

feature suggested in multisensory method. The user

can try or practice to write the syllable as many

times as they wish and can click on the erase button

as shown Figure 9 label (a) to erase the writing and

try again. At the beginning of this page there will be

a voice narration that explains the steps that should

be taken for the activity (writing). On completion of

the text, the user could do some exercises provided

in the courseware to gauge their understanding.

Figure 9: Screen snap for writing page.

4 THE COURSEWARE MODEL

Based on the current structure and contents of the

courseware, a model is proposed (Figure 10) that can

be used as guidelines for the development of

multimedia courseware for dyslexic children.

Figure 10: Courseware development model.

According to Figure 10, there are three

components that represent the overall courseware

model as in the box labelled A. These components

A MULTISENSORY MULTIMEDIA MODEL TO SUPPORT DYSLEXIC CHILDREN IN LEARNING

199

are the interrelated modules, i.e. the left marker and

the color palette for background.

The left marker was used to indicate the left side

of the courseware. The idea of having the left

marker was to reduce the problem faced by dyslexic

children who always gets confused between right

and left. This confusion may result in reading from

right. As such it was significant to have the left

marker displayed on the screen as this was found to

be suitable for a more advance courseware such as

for reading and comprehension. Besides that the user

can customize the background color using an in-built

color palette. This customization feature is essential

especially to reduce the scotopic sensitivity or

Meares-Irlen syndrome as explained earlier in the

literature.

Besides the three components explained above,

the courseware is bounded to the elements that

support the multisensory teaching as depicted in

Figure 10, box ‘B: The Elements’. These elements

are visual, audio and kinaesthetic content. These

elements are aligned with the multisensory concept

that has been discussed earlier. The kinaesthetic

elements for this courseware include the two way

interaction between the user and the courseware

where user can click the buttons, the syllable and

also changing the background color. In addition to

the above, the user can also practice writing the

syllable using the mouse.

The box labelled C: in Figure 10 represents the

interaction between the user and the courseware.

The two headed arrow symbolizes the two ways or

interactive communication between the user and the

courseware. The interactive communication between

user and the courseware was possible with the used

of buttons where user can control the flow of the

courseware that suited them.

5 COURSEWARE EVALUATION

In this research two evaluations were conducted

namely formative evaluation and summative

evaluation.

a. The formative evaluation was done among

normal children ages from 6 to 10. There were

six children involved in this evaluation. The

result from this evaluation is further discussed

in section 5.1.

b. The summative evaluations were conducted in

few schools that offer dyslexia intervention

class such as “Sekolah Kebangsaan Taman Tun

Dr. Ismail (2)” and also “Sekolah Kebangsaan

Taman Maluri.” This evaluation involved

dyslexic children and also teachers who are

teaching dyslexic children. However in this

paper only the overall performance statistical

experimental results are shown and discussed.

Complete results on pre and post test,

observation and interviews are discussed in

details in (Eze, 2010).

5.1 Results and Discussion

The overall performance statistical experimental

results are shown in Figure 11. The Figure shows

that 60% of the students who participated in the

experiment demonstrated a slight improvement in

their result. Another 30% of the students got the

same score for both pre-test and post-test. Most of

the students with the same result are in fact those

with a good score or the students who scored full

marks. Hence the use of the courseware did not

actually affect their performance for the reason that

they do not actually have problems in reading basic

Bahasa Melayu / Malay language. Figure 11 also

shows that 10% of the students had a slight drop in

their score. This might be due to carelessness or

difficulty to stay focus during the session.

Figure 11: Overall students performance.

Referring to the result and analysis discussed in

this section, it can be concluded that the courseware

developed based on the proposed model discussed in

section 4, benefited the dyslexic children especially

for those who are still in the beginning stage of

learning to read. It can be envisaged that the

performance might increase significantly if the

students were given more time to use the courseware

as their learning aid.

6 CONCLUSIONS

There are limited teaching and learning resources for

dyslexic children especially for Malay language. In

SIGMAP 2010 - International Conference on Signal Processing and Multimedia Applications

200

this paper, a preliminary courseware model that

could assist the courseware developer in developing

effective courseware for dyslexic children was

proposed. A prototype courseware was developed

and tested. In general the evaluation results showed

positive results whereby the students reading

performance of the Bahasa Melayu / Malay language

improved. It is believed that the courseware is being

well received by the children who took part in the

evaluation process. However further work is in

progress to revise and improve the proposed model

further.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to

UNITEN for the support provided and Dr.

Kirandeep Kaur Sidhu for her comments and proof

reading this paper. Special thanks is also due to

Sekolah Kebangsaan Taman Tun Dr. Ismail for

granting us the permission to conduct the

experiments and evaluation of this work at the

school.

REFERENCES

Advanogy. Learning Styles. Retrieved May 2009 from

http://www.learning-styles-online.com/inventory/

Memletics-Learning-Styles-Inventory.pdf

Ahmad, M. S., 2004. Managing Children with disabilities

to learn. PTS Professional Publishing Sdn. Bhd.

Malaysia.

Beachem, N., The potential of multimedia to enhance

learning for students with Dyslexia? Retrieved March

2008 from http://www.skillforaccess.org.uk/articles

Beatrice, J. A., 1994. Learning to study through critical

thinking? Retrieved March 2009 from

http://www.uu.edu./programs/tesl/ElementarySchool/l

earningstylesinventory.htm

Berninger, V. W., Raskind, W., Richards, Abbott, R.,

Stock, P. 2008. A Multidisciplinary Approach to

Understanding Development Dyslexia within

Working-Memory Architecture: Genotypes,

Phenotypes, Brain and Instruction. Development

Neuropsychology, Vol. 33, Issue 6, pp. 707 – 744.

Berita Harian Press, 2009. Dyslexia is it a Disease?

Newspaper Article.

Blevins, W. 2003. Phonics and the Beginning Reader.

Scholastic Professional Paper.

British Dyslexic Association, 2008. About Dyslexic.

Retrieved Mac 2008 from

http://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/about-dyslexia.html

Cecilia, S. L., Adam, T., Juliana, S., 2004. User Interface

Design for Developing Software for Handicapped

Children. 8

th

ERCIM Workshop, User Interface for all.

Vienna Austria.

Cutter, D., 2009. Identifying primary learning styles can

benefit children with special needs. Retrieved

November 2009 from http://www.ezineararticles.com/

Devaraj, S., Roslan, S., 2006. What is Dyslexia? A Guide

for Parents, teachers and counsellors. PTS

Professional Publishing Sdn. Bhd. Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia.

Devaraju, A., Techanamurthy, U. Zakaria, M. H.,

Zearatul, I., 2006. Development of a Multimedia

courseware with children with Dyslexia? A paper

presented at UPSI regional seminar & Exhibition

Research, Malaysia.

Douglas, S., 2008. What it means to be a visual learner.

Retrieved Mac 2009 from

http://www.education.com/magazine/Ed_Could_You_

Write_Down/

Dyslexia Association of Scotland. Dyslexia: A brief Guide

for Parents. Retrieved October 2008 from http://

www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk

Dyslexia Association of Singapore. The Orthon

Gillingham Multisensory Method. Retrieved March

2008 from http:// www.das.org.sg/malay/malay.htm

Elias, N., 1998. Why still use alphabets concept? National

issues seminar. UKM, Malaysia.

Eze, M., 2010. Adopting a Multisensory Method in

Modelling a Multimedia courseware to support

dyslexic children in learning to read Bahasa Melayu.

Master Thesis, University Tenaga Nasional, Malaysia.

Fleming, G., Tactile learning people who learn by doing.

Retrieved March 2009 from

http://www.homeworktips.about.com/od/homeworkpla

ce/a/tactile.htm

Grammatis, Y., Learning Styles.

Retrieved May 2009 from

http://www.chaminade.org/inspire/learnstl.htm

Green, C., N, 2006. Computer Assisted Learning for

Dyslexic Learners. Research paper in Dublin City

University, Ireland.

Gross, M., Voegeli, C., 2007. A multimedia framework

for effective language training. Elsevier Science

Journal: Computers and Graphics (31), pp. 761 – 777.

Gomez, C., 2004. Dyslexia in Malaysia. Supplementary

materials of the international book of dyslexia: Aguie

to practice and resources. Retrieved August 2008 from

http://www.wiley.com/legacy/wileychi/dyslexia/supp/

Malaysia.pdf

International Dyslexia Association. Multisensory

Teaching.

Retrieved May 2008 from http://www.interdys.org

James, B., 2009. What’s your learning style?

Retrieved March 2009 from

http://www.people.usd.edu/~bwjames/tut/learning-

style/

Karsh, K. G., 1992. Computer Aided Instruction: Potential

and reality. Springer-Verlang pp. 452 – 477.

Jester, C. 2000. Introduction to the DVC learning style

survey for college.

Retrieved May 2009 from

http://www.metamath.com/Isweb/dvclearn.com.htm

A MULTISENSORY MULTIMEDIA MODEL TO SUPPORT DYSLEXIC CHILDREN IN LEARNING

201

Lee, L., W, 2008. Development and validation of a

reading related assessment battery in Malay for the

purpose of dyslexia assessment. Annals of Dyslexia.

Retrieved February 2009 from http://www.findarticles

.com./p/articles/mi_qa3809/is_200806

Logsdon, A. Multisensory Techniques – Make

Multisensory teaching materials.

Retrieved October 2008 from

http://www.learningdisbalirties.about.com/od/instructi

onalmaterials/p/multisensory.htm

Learning Disabilities Association of America. 1998.

Learning Methods and Learning Disabilities.

Retrieved February 2008 from http://www.Idantl

.org/aboutId/teachers/teachers_reading/reading_metho

ds.asp

Lundberg, 1992. The computer as a tool to remediation in

the education with students with disabilities. Learning

disability quarterly (18), pp. 89 – 99.

Manjit, S. S. (2007). Development and Applications of

Technology Assisted Problem Solving Packages for

Engineering. PhD Thesis, University Malaya,

Malaysia.

Marcia, H. K., 1998. Structured, sequential, multisensory

teching: The Orton legacy. Annals of Dyslexia.

Retrieved March 2008 from http://

www.encyclopedia.com/doc1P3.html

New Straits Times, 2009. They Overcome Dyslexic. Can

Our Children? Newspaper Article.

Herod, L., 2002. Adult learning: From theory to practice.

Retrieved March 2009 from http://

www.nald.ca/adultlearningcourse/glossary.htm

Heymans, Y., 2007. Dyslexia. Retrieved March

2008 from http:// www.etni

.org.il/etninews/inter2d.htm

Hollowell, K. How to teach Phonics Reading. Retrieved

March 2008 from http://www.ehow.com/how.html

Hornsby, B., 1995. Overcoming Dyslexic: A straight-

forward guide for families and teachers. Vermilion

London.

Hutton, S., Helping auditory learners succeed. Retrieved

May 2009 from

http://www.education.com/magazine/article/auditory/l

earners

Irlen, H., 1991. Reading by colors. Overcoming dyslexia

and other raeding disabilities through the Irlen method.

Avery publishing group Inc. Garden City Park, New

York.

Rainger, R., 2003. A Dyslexic perspective on e-content

accessibility. TechDis Retrieved Mac 2009 from

http://www.new.techdis.ac.uk

Reid, J. M., 1987. The Learning style preferences of ESL

Students. TESOL quarterly.

Shaywitz, S., 2003. Overcoming Dyslexic: A New and

complete science based program for reading problems

at any level. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Silver, H. F., Strong, R. W., Perini, M. J. 2000. So each

may learn: Integrating learning styles and multiple

intelligence. Alexandria, VA.

Singleton, C., 2006. Computer and Dyslexia: Implications

for policies and practice. Computer resource centre.

University of Hull.

Tannahill, R., 2009. Strategies for Teaching Visual

Learners in the Classroom. Retrieved Mac 2009 from

http://www.tipstraining.suite101/article.cfm/visual_lea

rning_style

The Penn State York Nittany Success Centre. Auditory

Learners TechDis Retrieved Mac 2009 from

http://www.yk.psu.edu/learncenter/acskills/auditory.ht

ml

Union University Tennessee. Learning Styles Inventory.

Retrieved May 2009 from

http://www.uu.edu.programs/tesl/elementarySchool/le

arningstyleinventory.htm

Vaughan, T., 1996. Multimedia: Making it Work. Mc-

Graw-Hill Osborne, New York.

Vicari, S., Finzi. A., Menghini. A., Marotta. L., Baldi. S.,

Petrosini, L., 2005. Do children with development

Dyslexia have an implicit learning deficit? Journal of

Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 2005, (76) pp. 1392-

1397.

SIGMAP 2010 - International Conference on Signal Processing and Multimedia Applications

202