FROM DIGITAL ARCHIVES TO E-BUSINESS

A Case Study on Turning “Art” into “Business”

Rungtai Lin and Chih-Long Lin

Graduate School of Creative Industry Design, National Taiwan University of Arts, Taichung County, Taiwan

Keywords: e-Business, Digital archive, Cross cultural product design, Cultural difference.

Abstract: Along with Information Technology progress, E-business is becoming a key concept in the Internet and

electronic commerce world. However, in today’s intensely competitive business climate, innovative

products become central to E-business development. Furthermore, changes in consumer perceptions

regarding innovation are also important in E-business. Recently, creative industries are continually

emerging in electronic commerce and have the potential to become a key trend in E-business.

Understanding the E-business models for creative industries and helping designers to design “culture” into

products are important research issues, and issues not yet well covered. Therefore, this paper proposes an

ABCDE approach to illustrate how to transform “Archive” into “E-business”. In order to turn “Archive”

into “Business”, we first need “Creativity” and “Design”; only then can we transform innovative products

into “E-business.” Results presented herein create an interface for looking at the way E-business crosses

over cultures, and illustrate the interwoven experience of E-business and cultural creativity in the innovation

design process and electronic commerce world.

1 INTRODUCTION

Along with the progress of Information Technology,

E-business has become a common concept in the

Internet and electronic commerce world. However,

in today’s intensely competitive business climate,

innovative products become central in E-business

development (Amit & Zott, 2001; Ben Lagha,

Osterwalder & Pigneyr, 2001). To be successful,

innovative products must have a clear and

significant difference that is related to a market

place need. Furthermore, changes in consumer

perceptions regarding innovation are also important

in E-business. In addition, “Culture” plays an

important role in the design field, and “cross cultural

design” will be a key design evaluation point in the

future (Lin, 2007; Lin et al., 2007). Designing

“culture” into modern product will be a design trend

in the global market. E-business is considered to be

one of the pivotal components in cultural and

creative design industries, and this will have a

significant impact on consumer perception of

innovation.

In the global market - local design era,

connections between culture and E-business have

become increasingly close. For E-business, cultural

value-adding creates the core of product value. It’s

the same for culture; E-business is the motivation for

pushing the development of cultural and creative

industries forward. Recently, creative industries

have been continually emerging in electronic

commerce and can become a key trend in E-business.

Obviously, we need a better understanding of E-

business in cultural and creative design industries,

and not only for the global market but also for local

design. While cross-cultural factors become

important issues for product design in the global

economy, the intersection of E-business and creative

industries becomes a key issue making both local

design and the global market worthy of further in-

depth study (Dubosson, Osterwalder & Pigneyr,

2002; Osterwalder & Pigneyr, 2002)..

The importance of studying E-business has been

shown repeatedly in several studies in various areas

of the design field (Amit & Zott, 2001; Ben Lagha,

Osterwalder & Pigneyr, 2001). Despite the

recognized importance of E-business in cultural and

creative design industries, industries lack a

systematic approach to E-business. Understanding

the E-business models for creative industries and

turning “arts” into “business” for designers are

important research issues, and until now these topics

47

Lin R. and Lin C. (2010).

FROM DIGITAL ARCHIVES TO E-BUSINESS - A Case Study on Turning “Art” into “Business”.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 47-54

DOI: 10.5220/0002928200470054

Copyright

c

SciTePress

have not been well covered. In order to transform

“Archive” into “Business”, we first need

“Creativity” and “Design”, only then can results be

transformed into “E-business.” (Ko et al., 2009).

Therefore, this paper proposes an ABCDE approach

for illustrating how to transform “Archive” into “E-

business”. The ABCDE approach integrates the

difference between products and services of cultural

and creative design industries into the E-business

activities of current service development practice.

The ABCDE model provided illustrates how the

National Taiwan University of Arts (NTUA) has

established a link between E-business and cultural

and creative industries through Our Museum, Our

Studio and Our Factory respectively. Through the E-

business approach, we have been able to merge

design, culture, creativities and economy. The

approach also further illustrates some other

implications of the approach through the cultural

perspective. Results presented herein create an

interface for looking at the way E-business crosses

over cultures, and illustrates the interwoven

experience of E-business and cultural creativity in

the innovation design process and electronic

commerce world.

2 FROM OEM TO OBM

Taiwan’s industrial design is developing along with

its economic development. The design development

could be represented as a smile face, proposed by

the former ACER president Shi, from OEM

(Original Equipment Manufacture), ODM (Original

Design Manufacture), to OBM (Original Brand

Manufacture) as shown in Figure 1 (Lin et al., 2007).

Design for Innovation

OEM

ODM

OBM

Designing

Marketing

Branding

R & D

Manufacturing

Value-added By Design

Product

Standard

Product

Identity

Product

System

Product

Personality

Product

Integrity

Design for manufacturing Design for Service

Desi

g

n T

yp

es

Service Innovation Design & e Business Model

Innovation Design Business Model

Figure 1: From OEM to OBM in e Business.

Before 1980, OEM vendors in Taiwan reduced

costs to produce “cheap, high quality” products as a

strategy to become successful in the global

manufacturing industry. With the OEM style of

having “cost” but without a concept of “ price” in

mind, or just by knowing “cost down” but not

knowing “ value up”, these vendors created Taiwan’s

economic miracle by earning a low profit from

manufacturing. Those dependent upon hard-working

patterns from the OEM pattern became obstacles in

developing their own design. These vendors were

extremely busy producing products to meet

manufacturing deadlines; there was no time to

develop design capabilities, so that the environment

could not nurture design talents (Lin, 2007; Lin et al.,

2007).

After 1980, Taiwan enterprises began to develop

ODM patterns to extend their advantages in OEM

manufacturing. Taiwan’s government addressed a

series of measures to stimulate the nation’s

economic growth, including the “Production

Automation Skill Guidance Plan”, and the

“Assisting Domestic Traditional Industrial Skill

Plan”. These plans were to guide vendors to make

production improvements, to lower costs and to

increase competition. Starting from 1989, the

industry Bureau pushed the “Plan for Total

Upgrading of Industrial Design Capability” over

three consecutive five-year plans. The scheme

established working models by experienced design

scholars and students from universities for the

purpose of working on design. The design students

worked with the enterprises on specific projects to

set up a working pattern of industrial design based

on enterprises’ real needs (Lin, 2007;Lin et al.,

2007). Recently, product design in Taiwan has

stepped into the OBM era. In addition, cultural and

creative industries have already been incorporated

into the “National Development Grand Plan”,

demonstrating the government’s eagerness to

transform Taiwan’s economic development by

“Branding Taiwan” using “Taiwan Design” based on

Taiwanese culture (Lin, 2007; Lin et al., 2007).

There has been a recent shift from technological

innovation to E-business based on discovering new

opportunities in the marketplace. Companies are

more focused on adapting new technologies and

combining them in ways that create new experiences

and value for customers. With the development of

industrial trend, most companies gradually realized

that the keys to product innovation are not only

aspects of market and technology but also service

innovation design (Baxter, 1995; Zhang et al., 2003).

Ulrich and Pearson (1998) point out that service

design has received increased attention in the

academic and business communities over the past

ICE-B 2010 - International Conference on e-Business

48

decade. Both academics and practitioners

emphasized that the role of service design in

innovative product development relates not only to

aesthetics, but also to aspects such as ergonomics,

user-friendliness, efficient use of materials, and

functional performance (Gemser & Leenders, 2001).

However, we now live in a small world with a

large global market. While the market heads toward

“globalization”, design tends toward “localization.”

So we must “think globally” for the market, but “act

locally” for design. While E-business is under tough

competitive pressure from the developing global

market, it seems that the local design should be

focused on E-business in order to adapt innovation

to product design (Gregoire & Schmitt, 2006).

3 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

After reviewing the development of Taiwan’s

industrial design, it is clear that E-business is the

force pushing cultural and creative industries

development forward. The main purpose of this

paper is to study factors affecting the E-business

model. These factors are discussed in order to

understand E-business in cultural and creative

design industries. Then, a conceptual framework is

proposed for defining, classifying, assessing, and

modeling the E-business model for the cultural and

creative industries.

Cultural Objects

Design Information

Design Elements Creative Product

Identification

Translation Implementation

Investigation

Set a Scenario

Interaction

Tell a Story

Development

Write a Script

Implement

Design a Product

Cultural features Cultural productsDesign model

Conceptual Model

Digital Archive

Design Process

Information Value-Added Knowledge Value-Added Creativity Value-Added

Digital Archive Database

Design Knowledgebase

E-Learning

CAI System

Creative Product Design

CAD System

DesignerLearning Designing

Figure 2: The conceptual framework .

The conceptual framework in Figure 2 consists

of three main phases; conceptual model, digital

archive method, and design process. The conceptual

model focuses on how to extract cultural features

from cultural objects and then transfer these features

to the design model. The digital archive method

consists of three phases; identification (extract

cultural features from original cultural objects),

translation (transfer them to design information and

design elements) and implementation in the final

design of a cultural product (Lin, 2007; Lin et al.,

2009).

3.1 Conceptual Model

The conceptual model is shown in the top of Figure

2 and includes three stages: identifying cultural

features, building the design model and designing

cultural products. To accomplish the goal, there are

four steps including: selecting cultural objects,

transforming design information, extracting design

elements, and designing creative design products.

Then, implementation of the goal is broken into

three phases: identification, translation and

implementation which are described as follows (Lin,

2007; Lin et al., 2009):

Identification phase: the cultural features are

identified from original cultural objects including

the outer level of colors, texture, and pattern, the

mid level of function, usability, and safety (

Holzinger,

2005)

, and the inner level of emotion, cultural

meaning, and stories

(Heimgärtner, Holzinger & Adams,

2008). The designer uses the scientific method and

other methods of inquiry and hence is able to obtain,

evaluate, and utilize design information from the

cultural objects.

Translation phase: the translation phase

translates the design information to design

knowledge within a chosen cultural object. The

designer achieves some depth and experience of

practice in these design features and at the same time

is able to relate this design knowledge to design

problems in modern society. This produces an

appreciation for the interaction between culture,

technology, and society.

Implementation phase: the implementation phase

expresses the design knowledge associated with the

cultural features, the meaning of culture, an aesthetic

sensibility, and the flexibility to adapt to various

designs. At this time, the designer gains knowledge

of cultural objects and an understanding of the

spectrum of culture and value related to the cultural

object. The designer combines this knowledge with

his strong sense of design to deal with design issues

and to employ all of the cultural features in

designing a cultural product.

3.2 Digital Archives Database

How to build a digital archive database is shown in

the middle of Figure 2 and includes information

value-added, knowledge value-added, and creativity

value-added. The application of cultural features is a

FROM DIGITAL ARCHIVES TO E-BUSINESS - A Case Study on Turning "Art" into "Business"

49

powerful and meaningful approach to product

design. Consumers nowadays require a design which

is not only functional and ergonomic, but which also

stimulates emotional pleasure. Lin (2007) took a

cultural object called the Linnak as the example to

build a digital archive database for learning culture

through the internet and e-learning environment. The

data collected after studying its appearance,

usability, and cultural meaning is shown in Table 1.

A design-related format was used to match the

different items based on tribe, name of object, type,

image, material, color, appearance, usability, pattern,

form grammar, form structure, form style, inner

content, and original resource. These items covered

three levels of cultural characteristics and basic

information such as imagery icon, tribe, and name.

We propose that this information will serve as a

reference for designers during the product design

phase (2005; Hsu, 2004; Lin, Cheng & Sun, 2007).

Table 1: The format of the cultural features of Linnak.

1. The long- hooded pit viper or ancient figure pattern on the cup enhances the value of cup.

2. The twin-cup was mostly used in festival ceremonies to demonstrate a warm and harmonious spirit.

3. To drink with the twin cup represented the commitment in love between a male and female.

4. Drinking together represents eternal friendship.

Cultural

content

1. Single cup is created only for the chief to drink liquid in the Paiwan tribe. Sometimes it was used to

contain rice alcohol and to reward a hunting hero for demonstrating valor.

2. The twin -cup was created for use in wedding ceremonies where the bride and groom were required to

drink alcohol together.

3. The Tri-cup was created for the groom and bride and chief (a witness), who stands between groom and

bride to drink alcohol together which represents the greatest honor and wish for the couple.

Using

Scenario

Two drinkers are required to hold the handles with left and right hand on each when drinking alcohol.

Operation

Twin-cup, Single-cup and Tri-cup.

Classification

1. Embossment on handles with a variety of patterns.

2. Total length from 43cm to 91cm, pitch from 29cm to 42cm, and cup capacity from 300 to 600c.c.

3. Single cup with a rectangular column shape and handle on both sides.

4.The Linnak contains two rectangular cups, a beam bridge in between and a handle on both sides.

Principle of

formation

Figure, human-head, long-hooded pit viper pattern, Deer pattern

Pattern

Natural wood color or painting with colors

Color

Wood

Material

Picture

Paiwan, Rukai

Tribe

Drinking container

Type

Linnak or twin cup

Object

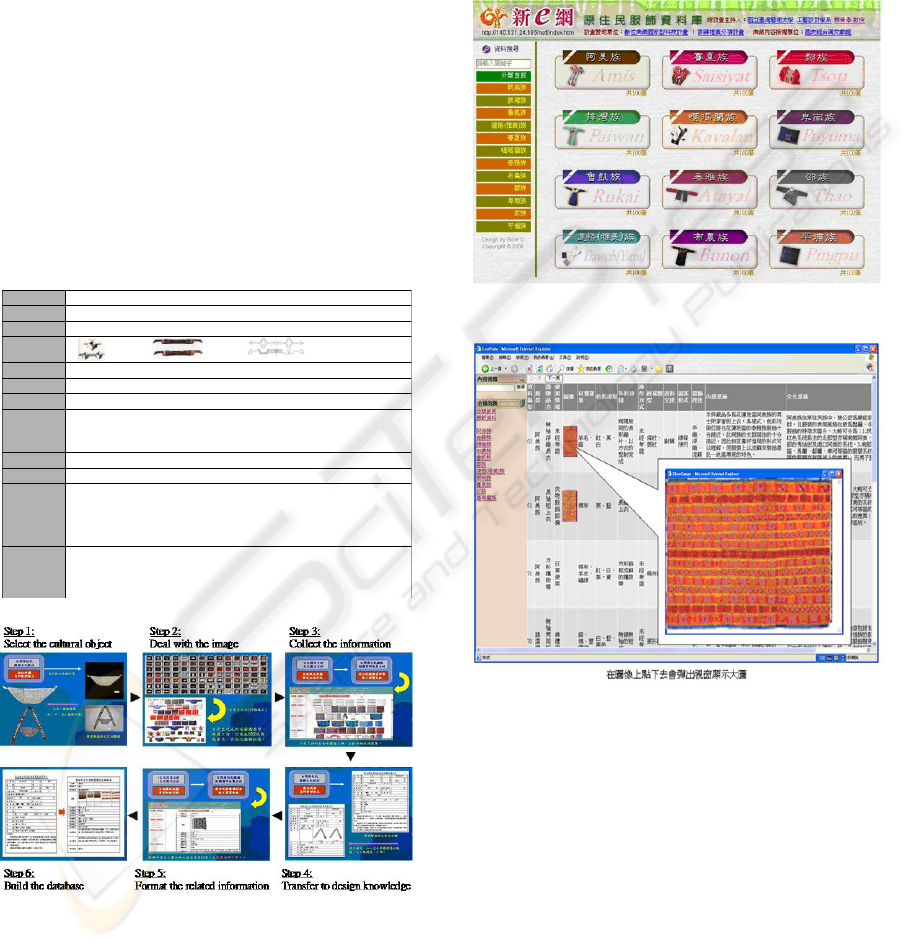

Figure 3: Process of building the database.

According to Table 1, a digital archive database

was built to help to understand both the hard and

soft contents of the cultural object. A process of

building a digital archive database included six steps

(Figure 3): (1) select the cultural object, (2) deal

with the image, (3) collect the information, (4)

transfer the information to design knowledge, (5)

format the related information, and (6) build the

database. In addition, a friendly interface was

provided to the designer for accessing the database

easily as shown in Figure 4 and 5 (Hsu, 2004; Lin,

Cheng & Sun, 2007).

Figure 4: Interface of the database.

Figure 5: Interface for referring the pattern.

3.3 Design Process

Based on the cultural product design model, the

cultural product is designed using scenario and

story-telling approaches. In a practical design

process, four steps are used to design a cultural

product: investigation (set a scenario), interaction

(tell a story), development (write a script), and

implementation (design a product) as shown in the

bottom of Figure 2 (Hekkert, 2003; Leong & Clark,

2003).

The four steps of the cultural product design

process are described as follows:

Step 1 / Investigation / Set a scenario: The first

ICE-B 2010 - International Conference on e-Business

50

step is to find the key cultural features in the original

cultural object and to set a scenario to fit the three

levels: the outer ‘tangible’ level, the mid ‘behavioral’

level, and the inner ‘intangible’ level. Based on the

cultural features, the scenario should consider the

overall environment such as economic issues, social

culture, and technology applications. This step seeks

to analyze the cultural features in order to determine

the key cultural features to represent the product.

Step 2 / Interaction / Tell a story: Based on the

previous scenario, this step focuses on a user-based

observation to explore the social cultural

environment in order to define a product with

cultural meaning and style derived from the original

cultural object. Therefore, some interactions should

be explored in this step, including interaction

between culture and technology, dialogue between

users and designers, and understanding the user’s

needs and cultural environment. According to the

interaction, a user-centered approach is used to

describe the user need and the features of the

product by story-telling.

Step 3 / Development / Write a script: This step

addresses concept development and design

realization. The purpose of this step is to develop an

idea sketch in text and pictograph form based on the

developed scenario and story. During this step, the

scenario and story might require modification in

order to transform the cultural meaning into a

logically sound cultural product. This step provides

a means to confirm or clarify the reason why a

consumer needs the product and rationale of how to

design the product to fulfill the users’ needs.

Step 4 / Implementation / Design a product: This

step deals with previously identified cultural features

and the context of the cultural products. At this point,

all cultural features should be listed in a matrix table

which will help designers check the cultural features

in the design process. In addition, the designer needs

to evaluate the product features, product meaning,

and the appropriateness of the product. The designer

may make changes to the prototype based on results

from the evaluation, and implement the prototype

and conduct further evaluations.

Based on the cultural product design model,

Figure 6 shows how to transfer the original object --

‘Pottery-pot’ from the Paiwan tribe into a design for

a modern bag. Different cultures use textile

containers designed for their own storage and

transportation needs. Unlike bags or containers made

from rigid materials such as clay or glass, textile

containers offer flexibility of use by adapting to

whatever item they are carrying. they also have the

great advantages of being non-breakable and easy to

store. Figure 7 shows how to use the Taiwan

aboriginal garments as the original cultural objects

to design modern bags. In addition, Figure 8

demonstrates the cultural features extracted from

Taiwan aboriginal garment culture and then

transformed into modern bag design.

Figure 6: The modern bag designed from a pottery pot.

Figure 7: The process of designing modern bags from

cultural objects.

Figure 8: Various bags from the Taiwan aboriginal

garment culture.

4 E-BUSINESS MODEL

After explaining why business executives and

academics should consider a rigorous approach to E-

business models, we introduce a new E-business

FROM DIGITAL ARCHIVES TO E-BUSINESS - A Case Study on Turning "Art" into "Business"

51

Model for the cultural and creative industries. The

new model is called “ABCDE Plan” which shows

that to turn “Art” into “Business”, we need

“Creativity” and “Design”, which allows the creative

products to be transformed into “E-business” as

shown in Figure 9.

OUR MUSEUM

OUR STUDIO

OUR FACTORY

Crafts

Innovation

BusinessDesign Service

Designing Marketing BrandingR & D

Manufacturing

Information

Intelligence

Innovation

Culture

Difference

Cultural

Features

Creative

Products

Value-added By Design

Design Types

Our Museum

NTUA Art Museum

Our Studio

NTUA Design Studio

Our Factory

NTUA Idea Factory

Innovation

E-Business

Art

Business

Design

Creativity

E - Business

Figure 9: The concept of e-Business model.

To implement the ABCDE plan, National

Taiwan University of Arts (NTUA) established an

art museum, known as “Our Museum”, in 2007 for

the purpose of linking professional teaching with the

museum’s research, education, and display

functions. At the same time the museum would

present cultural and aesthetic ideas about art and

artifacts to the public. Developing craftsmanship and

creativity as well as competences related to the arts

are of strategic importance to NTUA. Therefore, a

design studio, known as “Our Studio”, was

subsequently set up in the College of Design in

NTUA with the purpose of providing innovative

products. NTUA is located in the Taipei

metropolitan area, one of the most competitive

regions in Taiwan. This area contains a significant

concentration of craftsmanship and research

establishments, linked by various formal and

informal networks. Due to the challenging nature of

the cultural and creative industries, NTUA is

devoted to developing its regional and international

networks by operating a cultural and creative

industry park, known as “Our Factory.” NTUA has

established the link between “Art” and “Business”

and has combined “Creativity” and “Design”

through Our Museum, Our Studio and Our Factory

respectively. It is a new approach that integrates

design, culture, artistic craftsmanship, creativities

and service innovation design in cultural and

creative design industries (Roy & Riedel, 1976;

Stevens, Burley & Divine, 1999).

With the increasing globalization of the economy,

rapidly developing information technology, rapidly

growing market competition, shortening life cycles

of products and services, and increasing customer

demands, companies and public sector actors will

find it increasingly difficult to survive based on their

past operating models. Therefore, based on the

previous review of service design change, we

propose a conceptual framework to innovation

service design of cultural and creative design

industries by using the smile paradigm as shown in

Figure 10 (Ko et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009).

OUR MUSEUM

OUR STUDIO

OUR FACTORY

Crafts

Innovation

BusinessDesign Service

Designing Marketing BrandingR & D

Manufacturing

Information

Intelligence

Innovation

Culture

Difference

Cultural

Features

Creative

Products

Value-added By Design

Design Types

Our Museum

NTUA Art Museum

Our Studio

NTUA Design Studio

Our Factory

NTUA Idea Factory

Innovation

E-Business

Figure 10: e-Business for creative industries.

According to the smile paradigm, craftsmanship is

a part of Cultural creativity, and like the mouth in

the smile face, it must still go up through innovation

design and branding before it can become a

“business”. However, craftsmanship is not the

entirety of culture, nor is creativity the whole of

business; good craftsmanship at best earns

outsourcing money, like an OEM vendor. The key to

innovation design is to blend craftsmanship,

creativity and service design, and “branding” is the

key to any business (Ravasi & Lojacono, 2005).

In general, craftsmanship is the use of local

materials to develop localized skills; localization is

an important force behind the globalization of any

international conglomerate, especially in the

employment of cultural creativity. Crafted products

produced in small volume seek to represent the spirit

of “attention to details”, and are a demand on the

person, a representation of the person, an expression

by the person, and a story from the person.

Craftsmanship plumbs the depth of skills, while

creativity seeks the height of impression, and

branding asks for the width of acceptance. Only

through culture and creativity, by allowing

craftsmanship and creativity to facilitate branding,

ICE-B 2010 - International Conference on e-Business

52

can one makes one’s way in this field (Yair et al.,

1999, 2001;Veryzer, 1998; Voss & Zomerdijk,

2007).

The goal of the cultural and creative park is to

combine artistic craftsmanship and economy with

service design, and ultimately establish NTUA as a

distinctive trademark associated with the park. To

accomplish this goal, NTUA aims to combine

artistic craftsmanship from “Our Museum” with

cultural creativities from “Our Studio” in order to

result in aesthetics in business for “Our Factory”.

Creativity and business are the elements for reaching

an aesthetic economy. It is the concept of “Think

Globally - Act Locally” to process the “Digital

Archive” of Our Museum through the cultural

creativities of Our Studio, producing cultural

products in Our Factory in order to establish a local

industry making aesthetic and economical products

(Ko et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009).

The current development of the Cultural Creative

Park at NTUA is based on creative knowledge of

crafts elements and materials from Our Museum and

Our Studio. This cultural information is then

transferred into the creative industry. In the near

future, we will further implement this distinctive

mode of cultural creative production to promote the

concept of “Savoring Culture” which has the

potential to become a “Taiwan industry concept”.

We are encouraging more and more creative

products which contain colourful Taiwanese culture

and styles. By supporting the development of

cultural creative industry of NTUA, we can enjoy

the fruitful success of an aesthetic culture in the

creative industry (Lin et al., 2009).

5 CONCLUSIONS

With increasing global competition, E-business in

service innovation design is not merely desirable for

a company; it is a necessity. The importance of

studying E-business as part of service innovation

design has been shown repeatedly. However, there is

no systematic approach that covers E-business in

cultural and creative design industries. Therefore, a

new approach was proposed by applying E-business

in service innovation design in the domain of

cultural and creative design industries. The E-

business in service innovation design model is

presented herein to provide designers with a

valuable reference for designing “service” into a

successful cross-cultural product. The purpose of

this paper is to fulfill the aesthetic experience by

connecting design and culture. This is turn will

synthesize technology, humanity, cultural

creativities. Finally, we will achieve the aim of

promoting service design amongst the general

public.

For future studies, we need a better understanding

of the acculturation process not only for the E-

business in service design, but also for innovative

product design. While cultural features become

important issues in the interactive experiences of

users, the acculturation process between human and

culture becomes a key issue in cultural product

design and worthy of further in-depth study.

However, the effectiveness of using E-business in

cultural and creative industries can be further

enhanced. This can be done by incorporating more

information of best practice in service industries into

E-business in cultural and creative design industries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper based on the author’s recent paper (Lin,

2007, 2009). I gratefully acknowledge the support

for this research provided by the National Science

Council under Grant No. NSC-98-2410-H-144-009,

and NSC-98-2410-H-144-010. The author wishes to

thank the various students who have designed the

products presented in this paper, especially, C.H.

Hsu, H. Cheng, M.X. Sun, E.T., Kuo, and colleagues

who have contributed to this study over the years,

specially, Dr. J. G. Kreifeldt and Mr. T.U. Wu.

REFERENCES

Amit, R. and Zott, C., 2001. Value Creation in E-business.

Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22, No. 6/7,

Special Issue: Strategic Entrepreneurship:

Entrepreneurial Strategies for Wealth Creation (Jun. -

Jul., 2001), 493-520.

Ben Lagha, S., Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., 2001.

Modeling E-business with eBML, 5e Conférence

International de Management des Réseaux

d’Entreprises, Mahdia, October 25-26.

Berkley, B.J., 1996. Designing services with function

analysis. Hospitality Research Journal, Vol. 20, No.1,

73-100.

Baxter M. 1995. Product design: a practical guide to

systematic methods of new product development.

Chapman & Hall, London, UK.

Dubosson, M, Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y., 2002.

eBusiness Model Design, Classification and

Measurements, Preprint on an article accepted for

publication in Thunderbird International Business

Review, January 2002, vol. 44, no. 1: 5-23

FROM DIGITAL ARCHIVES TO E-BUSINESS - A Case Study on Turning "Art" into "Business"

53

Grégoire, B. & Schmitt, M., 2006. Business service

network design: from business model to an integrated

multi-partner business transaction. Proceedings of the

8th IEEE International Conference on E-Commerce

Technology and the 3rd IEEE, International

Conference on Enterprise Computing, E-Commerce,

and E-Services (CEC/EEE’06)

Gemser G., & Leenders M., 2001. How integrating

industrial design in the product development process

impacts on company performance. The Journal of

Product Innovation Management 18, 28-38.

Hekkert, P., Snelders, D., & van W ieringen, P. C. W.,

2003. Most advanced, yet acceptable: Typicality and

novelty as joint predictors of aesthetic preference in

industrial design. British Journal of Psychology, 94(1),

111-124.

Holzinger, A. (2005). Usability Engineering for Software

Developers. Communications of the ACM,48,1, 71-74.

Heimgärtner, R., Holzinger, A., Adams, R. (2008). From

Cultural to Individual Adaptive End-User Interfaces:

Helping People with Special Needs. In: Lecture Notes

in Computer Science (LNCS 5105), (pp. 82–89).

Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

Hsu, C.H., 2004. An application and case studies

of Taiwanese aboriginal material civilization confer to

cultural product design. Unpublished master’s thesis,

Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Ko, Y.Y., Lin, P.H. & Lin, R., 2009. A Study of Service

Innovation Design in Cultural and Creative Industry.

HCI (14) 2009: 376-385.

Leong, D. & Clark, H.. 2003. Culture -based knowledge

towards new design thinking and practice - A dialogue.

Design Issues, 19(3), 48-58.

Lin, R., & Kreifeldt, J. G., 2001. Ergonomics in Wearable

Computer. International Journal of Industrial

Ergonomics 27, Special Issue : Ergonomics in Product

Design, 259-269.

Lin, R., 2007. Transforming Taiwan Aboriginal Cultural

Features Into Modern Product Design-A Case Study

of Cross Cultural Product Design Model. International

Journal of Design, 1(2), 45-53.

Lin, R., Cheng, R., & Sun, M. X., 2007. Digital Archive

Database for cultural product design. HCI

International 2007, 22-27 July, Beijing, P.R. China.

paper- ID:825, Proceedings Volume 10, LNCS_4559,

ISBN: 978-3-540-73286-0.

Lin, R., Sun, M.X., Chang, Y.P., Chan,Y.C., Hsieh,Y.C.,

& Huang,Y.C., 2007. Designing “Culture” into

Modern Product --A Case study of Cultural Product

Design. HCI International 2007, 22-27 July, Beijing,

P.R. China. Paper-ID:2467, Proceedings Volume 10,

LNCS_4559, ISBN: 978-3-540-73286-0.

Lin, R., Lin, P.B., Shiao, W.S. & Lin, S.H., 2009. Cultural

Aspect of Interaction Design beyond Human-

Computer Interaction. HCI (14) 2009: 49-58.

Martin, C.R. & Horne, D.A., 1993. Services innovation:

Successful versus unsuccessful firms. International

Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 4, No.

1, 49-65

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y., 2002. An E-business

Model Ontology for Modeling E-business. 15th Bled

Electronic Commerce Conference e-Reality:

Constructing the e-Economy, Bled, Slovenia, June 17

- 19, 2002.

Ravasi, D., & Lojacono, G., 2005. Managing design and

designers for strategic renewal. Long range planning,

38, 51-77.

Roy R., & Riedel J., 1997. Design and innovation in

successful product competition. Technovation 17,

537-548.

Stevens, G., Burley, J., & Divine, R., 1999. Creativity +

business disciplines = higher profits faster from new

product development. Journal of Product Innovation

Management 16, 455-468.

Ulrich, K. T., & Pearson, S., 1998. Assessing the

importance of design through product archaeology.

Management Science 44, 352-369.

Veryzer, R. W., 1998. Discontinuous innovation and the

new product development process. Journal of Product

Innovation Management 15, 304-321.

Voss, C. & Zomerdijk, L., 2007. “Innovation in

Experiential Services – An Empirical View”. In: DTI

(ed). Innovation in Services. London: DTI. pp.97-134.

Wu, T.Y., Hsu, C.H., and Lin, R., 2004. The study of

Taiwan aboriginal culture on product design, In

Redmond, J., Durling, D. & De Bono, A. (Eds.),

Proceedings of Design Research Society International

Conference. Paper #238, DRS Futureground, Monash

University, Australia.

Yair, K., Press, M. & Tomes A., 2001. Crafting

competitive advantage: crafts knowledge as a strategic

resource. Design Studies, 22, 377-394.

Yair, K., Tomes, A. & Press, M., 1999. Design

through marking- crafts knowledge as facilitator to

collaborative new product development, Design

Studies, 20(6), 495-515.

Zhang, J., Tan, K.C., & Chai, K.H., 2003. Systematic

Innovation in Service Design Through TRIZ. In the

Proceedings of the EurOMA-POMS 2003 Annual

Conference, Cernobbio, Lake Como, Italy, June 16th -

18th, 2003, Vol 1, pp. 1013-1022.

ICE-B 2010 - International Conference on e-Business

54