RISK ANALYSIS FOR INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROLS

Joris Hulstijn

IT Audit, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Jaap Gordijn

Faculty of Sciences, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Keywords:

Governance and control, Risk, Value modeling.

Abstract:

Existing early requirements engineering methods for dealing with governance and control issues do not ex-

plicitly support comparison of alternative solutions and have no clear semantics for the notion of a control

problem. In this paper we present a risk analysis method for inter-organizational business models, which

is based on value modeling. A risk is the likelihood of a negative event multiplied by its impact. In value

modeling, the impact of a control problem is given by the missing value. The likelihood can be estimated

based on assumptions about trust and about the underlying coordination model. This allows us to model the

expected value of a transaction. The approach is illustrated by a comparison of the risks of different electronic

commerce scenarios for delivery and payment.

1 INTRODUCTION

New business models are often based on coopera-

tion among companies in a network organization,

made possible by information technology (Tapscott

et al., 2000). For the development of business mod-

els and the subsequent design and implementation of

inter-organizational information systems, practition-

ers need a good understanding of the governance and

control of the network. What is the risk that an-

other participant will default? How can we make

sure that participants, on whom the joint success de-

pends, will behave as agreed? When participants who

do not know each other need to collaborate, initially

lack of trust is likely (Gambetta, 1988). To overcome

the initial lack of trust, inter-organizational control

measures are needed (Williamson, 1979; Bons et al.,

1998). Such measures can take the shape of contrac-

tual arrangements or supervision by a trusted third

party. Governance and control measures affect sys-

tem requirements and need to be designed and agreed

on explicitly. That means that governance and control

issues should be addressed during early requirements

engineering (Yu, 1997; Mylopoulos et al., 1997).

A recently developed method for modeling inter-

organizational control problems and their solutions is

e3-control (Kartseva, 2008; Kartseva et al., 2005).

The e3-control method is based on e3-value, a tech-

nique for representing and reasoning about networked

business models with the perspective of economic

value (Gordijn and Akkermans, 2003). Networks

should respect the principle of economic reciprocity:

for all services or goods delivered to the network, the

network should provide services or goods of equal

value in return. The e3-value method is supported

by a graphical modeling tool with some reasoning

capabilities to determine well-formedness. An al-

ternative would be dependency graphs, as in i* (Yu,

1997). Value models can be translated into depen-

dency graphs (Gordijn et al., 2006).

However, current conceptual modeling tools have

several limitations:

1. There are usually many different ways to deal

with governance and control. Current conceptual

modeling tools offer no support for prioritizing or

selecting among those alternative scenarios.

2. The conceptual modeling tools should help to

identify governance and control problems (threats

or vulnerabilities), represented in e3-control by a

dashed arrow. Currently, the notion of a control

problem does not have a precise semantics.

We address these limitations by extending the value

modeling framework with risk analysis. Generally,

risk is modeled as the product of the likelihood and

the impact of an event on the proper functioning of

314

Hulstijn J. and Gordijn J. (2010).

RISK ANALYSIS FOR INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROLS.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Information Systems Analysis and Specification, pages

314-320

DOI: 10.5220/0002964603140320

Copyright

c

SciTePress

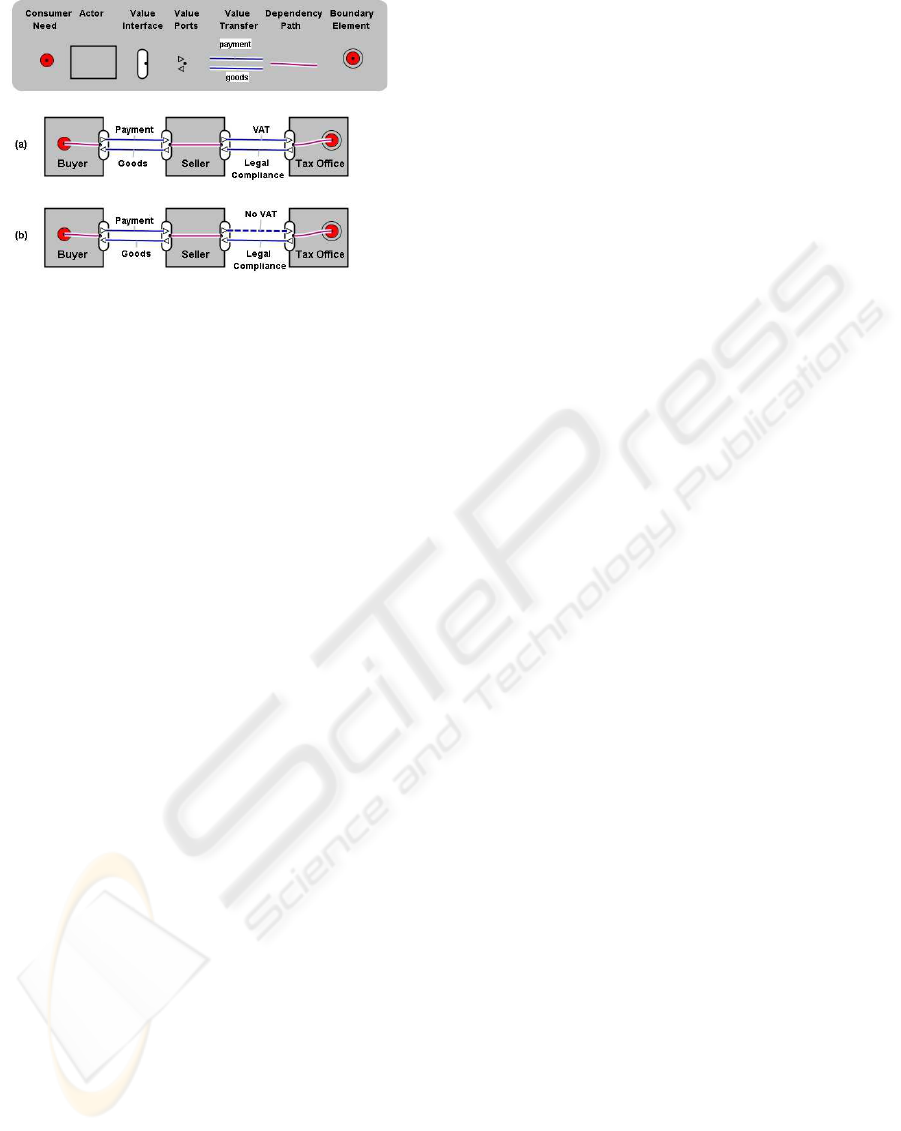

Figure 1: Example of an e3-value model of a purchase with tax payment: (a) ideal situation (b) sub-ideal situation with a

control problem (dashed arrow).

do not need to come from the same actor, but

they must be connected by a single value inter-

face: only when the incoming value is guaranteed,

the outgoing value be transferred.

R2. A dependency path may not contain any cycles,

so formally it is a directed acyclic graph. Cycles

would be meaningless; it would imply that a seller

would (indirectly) buy its own products.

A tool allows analysts to draw value networks and

perform validity checks (www.e3value.com). The

tool can generate so net value flow sheets, listing the

incoming and outgoing value flows, as a first indica-

tion of the economic feasibility of a network. The

tool can sum the net value flows of all actors in a

market segment. It can also concatenate a time se-

ries of value models, adding all the net value flows

over a certain period, using discounted net present

value (Derzsi et al., 2007).

2.2 Modeling Control Problems

In e3-value it is assumed that value transfers are

‘ideal’: they take place according to the agreements

between network participants, and norms and regula-

tions. But reality may be sub-ideal: actors commit

fraud or make unintentional errors, e.g. participants

will not pay, or will not deliver the (right) goods. Of-

ten, but not always, this implies that participants do

not respect the principle of economic reciprocity R1),

or that dependency paths contain loops (R2). All in-

valid e3-value models indicate a sub-ideal situation,

but not all sub-ideal situations correspond to an in-

valid model: a control problem may be hidden on the

coordination level. The specific value transfer which

is compromised by a sub-ideal situation is graphically

represented by a dashed arrow. By analogy, such a

transfer is called a sub-ideal value transfer. For ex-

ample, Figure 1(b) shows a sub-ideal value transfer in

which the seller does not pay VAT tax.

In the current interpretation of e3-control, dashed

arrows are only a notational convention. They denote

a value transfer that leads to a value leak: a situation

in which there is insufficient incoming value for an ac-

tor to compensate the outgoing value. The implemen-

tation of one value transfer may require several op-

erational and communication activities (Weigand and

de Moor, 2003). Value models abstract away from the

coordination aspect of such activities, but the order

in which activities take place, and the choice of actor

performing the activities, forms a crucial part of many

control mechanisms (Romney and Steinbart, 2006).

So in addition to value models, we need process mod-

els and coordination models (Wieringa, 2008). In this

paper, we use UML interaction diagrams to represent

interaction sequences (Rumbaugh et al., 1999) .

Figure 1: Example of an e3-value model of a purchase with

tax payment: (a) ideal situation (b) sub-ideal situation.

an organization: risk = likelihood × impact. In our

case, the impact of a missing value transfer is al-

ready given by the value model. The likelihood is

much harder to identify. We propose to apply existing

risk frameworks (e.g. NIST 800-30; ISO/IEC 27005),

and organize identified threats and vulnerabilities into

a Bayesian network, based on the dependencies im-

plicit in the value model, as well as assumptions about

the domain, the participants and the presence or ab-

sence of specific control measures. The main contri-

bution of the paper is a re-interpretation of value mod-

els, where value transfers are understood as expected

value transfers. Risk estimates provide a semantics

for control problems, and can be used to select or pri-

oritize among control scenarios.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 de-

scribes e3-value and e3-control. Section 3 presents

illustrative scenarios for delivery and payment. Sec-

tion 4 describes the risk analysis method.

2 VALUE AND CONTROL

An e3-value model provides a conceptual model of

the value transfers in a business network, encoded

in the e3-value ontology (Gordijn and Akkermans,

2003). Initially we apply the e3-value ontology for

the description of organizations that behave in com-

pliance with procedures and regulations. This is

called an ideal situation. Sub-ideal situations result-

ing from threats or vulnerabilities can be expressed

using e3-control, a modification of the e3-value on-

tology (Kartseva et al., 2005).

The e3-value constructs have a graphical notation.

Figure 1(a) shows an example of a buyer who obtains

goods from a seller and offers a payment in return.

The seller is obliged to pay value-added tax (VAT).

This can be conceptualized by the following e3-value

constructs (in bold). Actors, such as the buyer, seller,

and the tax office are economically independent enti-

ties. Actors transfer value objects (payment, goods,

VAT) by means of value transfers, depicted by labeled

arrows. A value interface models the principle of

economic reciprocity: actors are only willing to trans-

fer a value in return for some other value object. A

value interface consists of value ports, to for offer-

ing and requesting value objects. Actors may have

a consumer need, which, following a dependency

path will result in the transfer of value objects. Trans-

fers are either dependent on other transfers, or lead

to a boundary element. Dependency paths can be

connected by a choice fork (triangle) or parallel ex-

ecution (bar). Monetary values can be assigned to

value transfers, in order to evaluate the relative prof-

itability of a business idea. A tool allows analysts

to draw value networks and perform validity checks

(www.e3value.com). We consider two requirements

for internal validity: (R1) A value interface should

have at least one ingoing and at least one outgoing

value port. This corresponds to the principle of eco-

nomic reciprocity. (R2) A dependency path may not

contain any cycles.

In e3-value value transfers are assumed to be

‘ideal’, but reality may be sub-ideal: actors commit

fraud or make unintentional errors, e.g. participants

will not pay, or will not deliver the (right) goods. Of-

ten, but not always, this implies violation of the prin-

ciple of economic reciprocity. All invalid e3-value

models indicate a sub-ideal situation, but not all sub-

ideal situations correspond to an invalid model: a con-

trol problem may be hidden on the coordination level.

The specific value transfer which is compromised by

a sub-ideal situation – a ‘value leak’ – is graphically

represented by a dashed arrow. For example, Fig-

ure 1(b) shows a sub-ideal value transfer in which the

seller does not pay VAT tax. Currently, dashed arrows

are only a notational convention.

The implementation of one value transfer may re-

quire several operational and communication activi-

ties (Weigand and de Moor, 2003). Value models ab-

stract over the coordination aspects, but the order in

which activities take place and the choice of actor per-

forming the activities, forms a crucial part of many

control mechanisms (Romney and Steinbart, 2006).

So in addition to value models, we need process and

coordination models (Wieringa, 2008). We use UML

interaction diagrams for this purpose.

3 E-COMMERCE EXAMPLE

The example is concerned with a simple transaction,

shown in Figure 2: a buyer and a seller are exchanging

RISK ANALYSIS FOR INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROLS

315

money in return for goods. Think of a transaction ini-

tiated by eBay or some other electronic marketplace.

Delivery will take some time, so at least one of the

parties will depend on the other. We assume that par-

ticipants do not know each other, and have no other

reasons to trust one another. Moreover, we assume

that initially no additional control measures, such as

eBay’s reputation mechanism, are in place. Similar

scenarios are discussed in the literature on transaction

costs and electronic marketplaces (Williamson, 1979;

Hu et al., 2004). See (Wieringa, 2008) for coordina-

tion models of a similar scenario.

The e3-control method prescribes that the design

of controls proceeds according to the following three

steps (Kartseva et al., 2005):

1. Identify an ideal configuration of value transfers

in a network.

2. By analyzing coordination models and incen-

tives, identify a possible sub-ideal situation (threat

and/or vulnerability), with opportunities for er-

rors, opportunistic behavior or fraud. These in-

dicate the presence of a control problem.

3. For each identified sub-ideal situation, construct a

solution, i.e., a set of control measures to mitigate

the control problem.

The result of step 3 is a repaired configuration of value

transfers. Newly introduced controls may for example

trigger new value transfers, which also need to be con-

trolled. Therefore steps 1 until 3 should be repeated

for as many sub-ideal situations (threats or vulnera-

bilities) as are deemed relevant for the sustainability

of a business model. After such an exercise, the ana-

lyst is left with a set of possible scenarios for dealing

with the control problem. In this paper we intend to

provide a risk estimate, which will allow one to make

a selection or to prioritize among those alternative so-

lutions. We will first give an extensive example.

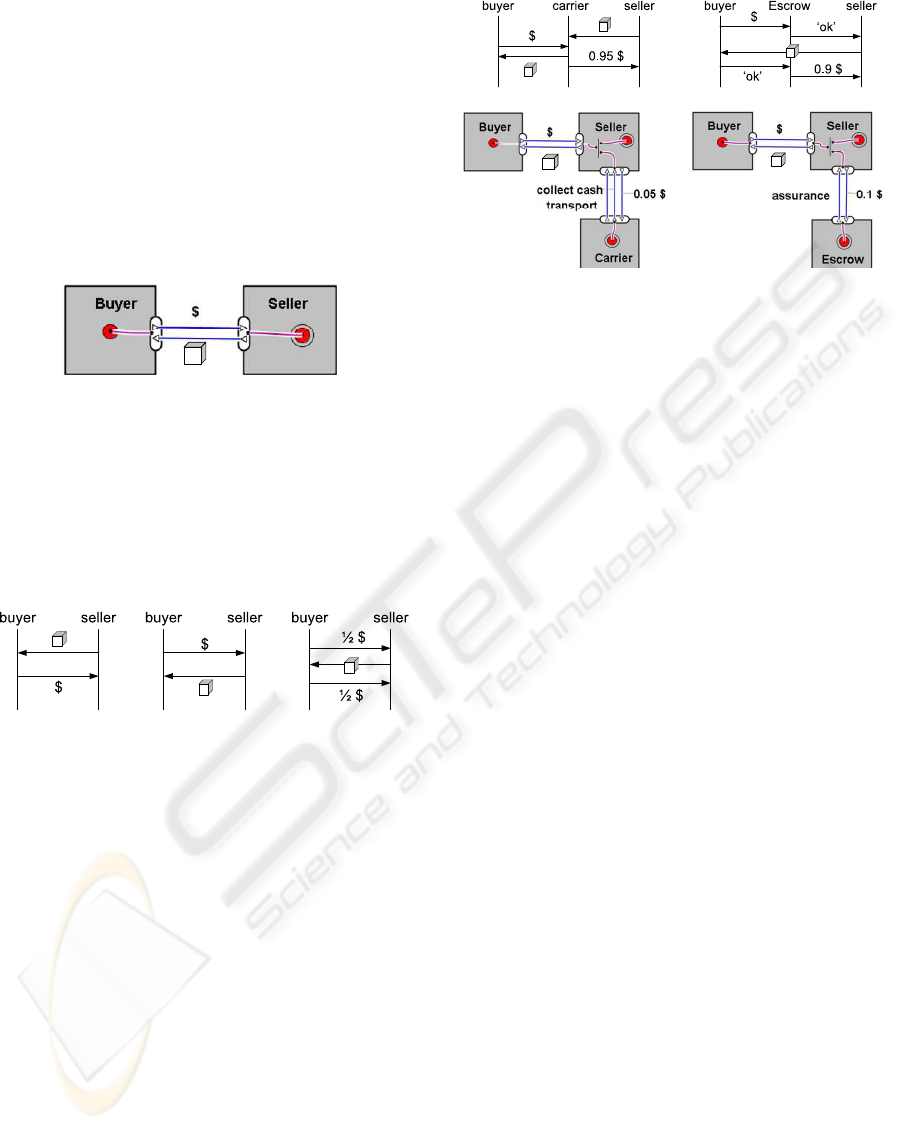

3 EXAMPLE: TRANSACTION

RISKS IN E-COMMERCE

The example is concerned with a simple transaction,

shown in Figure 2: a buyer and a seller are exchang-

ing money in return for goods, in some e-commerce

setting. Think of a transaction initiated by eBay or

some other electronic marketplace. This means that

delivery will take some time, so at least one of the

parties will depend on the other, without being able to

control the other party. We assume that participants

do not know each other, and have no other reasons

to trust one another. Moreover, we assume that ini-

tially no additional control measures, such as eBay’s

reputation mechanism, are in place. Similar scenarios

are discussed in the literature on transaction costs and

electronic marketplaces (Williamson, 1979; Hu et al.,

2004). See (Wieringa, 2008) for more elaborate coor-

dination models of a similar scenario.

A mutual value transfer often consists of several

operational activities, which are treated in e3-value as

an inseparable transaction, similar to e.g. transactions

in a database. By varying the order in which opera-

tional activities take place we get different scenarios,

with different risks for the participants (Figure 3). The

Figure 2: Value model of a generic e-commerce setting

Scenario 1: Scenario 2: Scenario 3:

pay before delivery deliver before paying down payment

Figure 3: Scenarios for delivery and payment.

example shows that coordination models are indeed

necessary to deal with control issues.

3.1 Scenario’s for delivery and payment

Which control scenario is selected, generally depends

on a multi-party negotiation process. We can expect

that a ‘dominant player’ in the market will be able

to impose his or her preferred scenario on the other

participants. In some cases, no player will be able to

impose their preferred option, so some form of com-

promise must be reached. First we consider scenarios

that do not involve external parties.

1. Pay before delivery. Suppose that the buyer must

pay before the seller will deliver the goods. This is

the preferred option for the seller. The buyer however

runs the risk that the goods will not be delivered, and

that the money cannot be recovered. This situation

is common in a market where sellers are dominant

enough to dictate the conditions of trade.

2. Deliver before paying. Suppose that the seller

must deliver the goods, before the buyer will be will-

ing to pay. This option is preferred by the buyer. The

seller now runs the risk that the goods will not be paid

for. This situation is common when the buyer can dic-

tate the conditions of trade.

3. Down payment. If neither the buyer nor the seller

is willing to ‘go first’, a compromise may be reached

in the form of a down payment: the buyer will pay for

example 50% of the agreed price beforehand. This

reduces the risk of the seller of not being paid at all.

The additional 50% will be paid after delivery, reduc-

ing the risk of the buyer that the goods will not be

delivered. Depending on the value, the delay between

ordering and delivery, and the relative dominance of

the players, other percentages may be used.

Next we consider two scenarios where external

parties help to solve participants’ control problems.

Figure 2: Value model of a generic e-commerce setting

A transaction often consists of several operational

activities. By varying the order in which operational

activities take place we get different scenarios, with

different risks for the participants (Figure 3). Which

control scenario is selected, generally depends on a

multi-party negotiation process.

The e3-control method prescribes that the design

of controls proceeds according to the following three

steps (Kartseva et al., 2005):

1. Identify an ideal configuration of value transfers

in a network.

2. By analyzing coordination models and incen-

tives, identify a possible sub-ideal situation (threat

and/or vulnerability), with opportunities for er-

rors, opportunistic behavior or fraud. These in-

dicate the presence of a control problem.

3. For each identified sub-ideal situation, construct a

solution, i.e., a set of control measures to mitigate

the control problem.

The result of step 3 is a repaired configuration of value

transfers. Newly introduced controls may for example

trigger new value transfers, which also need to be con-

trolled. Therefore steps 1 until 3 should be repeated

for as many sub-ideal situations (threats or vulnera-

bilities) as are deemed relevant for the sustainability

of a business model. After such an exercise, the ana-

lyst is left with a set of possible scenarios for dealing

with the control problem. In this paper we intend to

provide a risk estimate, which will allow one to make

a selection or to prioritize among those alternative so-

lutions. We will first give an extensive example.

3 EXAMPLE: TRANSACTION

RISKS IN E-COMMERCE

The example is concerned with a simple transaction,

shown in Figure 2: a buyer and a seller are exchang-

ing money in return for goods, in some e-commerce

setting. Think of a transaction initiated by eBay or

some other electronic marketplace. This means that

delivery will take some time, so at least one of the

parties will depend on the other, without being able to

control the other party. We assume that participants

do not know each other, and have no other reasons

to trust one another. Moreover, we assume that ini-

tially no additional control measures, such as eBay’s

reputation mechanism, are in place. Similar scenarios

are discussed in the literature on transaction costs and

electronic marketplaces (Williamson, 1979; Hu et al.,

2004). See (Wieringa, 2008) for more elaborate coor-

dination models of a similar scenario.

A mutual value transfer often consists of several

operational activities, which are treated in e3-value as

an inseparable transaction, similar to e.g. transactions

in a database. By varying the order in which opera-

tional activities take place we get different scenarios,

with different risks for the participants (Figure 3). The

Figure 2: Value model of a generic e-commerce setting

Scenario 1: Scenario 2: Scenario 3:

pay before delivery deliver before paying down payment

Figure 3: Scenarios for delivery and payment.

example shows that coordination models are indeed

necessary to deal with control issues.

3.1 Scenario’s for delivery and payment

Which control scenario is selected, generally depends

on a multi-party negotiation process. We can expect

that a ‘dominant player’ in the market will be able

to impose his or her preferred scenario on the other

participants. In some cases, no player will be able to

impose their preferred option, so some form of com-

promise must be reached. First we consider scenarios

that do not involve external parties.

1. Pay before delivery. Suppose that the buyer must

pay before the seller will deliver the goods. This is

the preferred option for the seller. The buyer however

runs the risk that the goods will not be delivered, and

that the money cannot be recovered. This situation

is common in a market where sellers are dominant

enough to dictate the conditions of trade.

2. Deliver before paying. Suppose that the seller

must deliver the goods, before the buyer will be will-

ing to pay. This option is preferred by the buyer. The

seller now runs the risk that the goods will not be paid

for. This situation is common when the buyer can dic-

tate the conditions of trade.

3. Down payment. If neither the buyer nor the seller

is willing to ‘go first’, a compromise may be reached

in the form of a down payment: the buyer will pay for

example 50% of the agreed price beforehand. This

reduces the risk of the seller of not being paid at all.

The additional 50% will be paid after delivery, reduc-

ing the risk of the buyer that the goods will not be

delivered. Depending on the value, the delay between

ordering and delivery, and the relative dominance of

the players, other percentages may be used.

Next we consider two scenarios where external

parties help to solve participants’ control problems.

Figure 3: Scenarios for delivery and payment.

1. Pay before Delivery. The buyer must pay before

the seller will deliver the goods. This is the preferred

option for the seller. The buyer runs the risk that the

goods will not be delivered and that the money cannot

be recovered.

2. Deliver before Paying. The seller must deliver the

goods, before the buyer will pay. This option is pre-

ferred by the buyer. The seller runs the risk that the

goods will not be paid.

3. Down Payment. A compromise may be reached in

the form of a down payment: the buyer will pay for

example 50% of the agreed price beforehand. This

reduces the risk of the seller of not being paid at all.

The additional 50% will be paid after delivery, reduc-

ing the risk of the buyer that the goods will not be

delivered. Other percentages may be used.

4. Cash on Delivery. The goods are paid to the car-

Scenario 4: Scenario 5:

cash on delivery Escrow

Figure 4: Scenarios for delivery and payment with the help

of third parties.

4. Cash on Delivery. In this scenario the goods are

paid to the carrier who delivers the goods. The buyer

can inspect the goods before paying, reducing her

risks. The carrier acts as a payment guarantee, re-

duces the risks for the seller. This ‘cash collection’

can be seen as an additional service, in return for a

fee. In this version, the service is paid for by the

seller. Here we assume the seller will trust the car-

rier. In practice, the seller will often take additional

control measures to ensure the carrier will not pocket

the money. Think of a receipt signed by the buyer,

which must be shown by the carrier afterwards.

5. Escrow. In this scenario, participants may hire a

trusted third party to ensure both delivery and pay-

ment. This party acts as an Escrow: a controlled cus-

todian. The procedure runs as follows. First the buyer

pays the agreed sum to the Escrow. The Escrow no-

tifies the seller that payment has arrived. The seller

subsequently delivers the goods. Now the buyer no-

tifies the Escrow of delivery, and thereby releases the

payment, with a certain percentage deducted as a fee.

The service delivered by the Escrow may be termed

‘assurance’. The party mostly in need of assurance

will pay the fees. Here we assume the seller will pay.

3.2 Ranking and Negotiating Scenarios

Now we will try to make some comparisons between

scenarios. We start from the point of view of the

seller. Suppose p

b

represents the seller’s estimate of

the likelihood that the buyer will pay beforehand, with

0 < p

b

< 1. This represents the initial trust the seller

has in the buyer’s willingness to pay, without any ad-

ditional control measures. When buyers are from a

trustworthy community p

b

will be relatively high, for

example 0.6. But on the internet, p

b

could be as low

as 0.3. Suppose furthermore that the seller’s value for

the goods is v

s

, their price, with v

s

> 0, and that the

fraction paid beforehand as down payment is a, with

0 < a < 1. For example, the down payment could be

50%. Moreover, we assume the seller himself is hon-

est, and that the buyer really wants to have the goods.

Now we can put estimates on the scenarios as follows.

Seller’s expected value:

Scenario 1: v

s

,

because payment before delivery is certain.

Scenario 2: p

b

v

s

,

because the likelihood of payment is p

b

.

Scenario 3: av

s

+ p

b

(1 − a)v

s

,

because after the first instalment (av

s

), the

likelihood of the second instalment is p

b

.

It follows that regardless of the values of v

s

, p

b

and

a, we have the following ranking: Scenario 1 > Sce-

nario 3 > Scenario 2. So when entering negotiations,

the seller will prefer to get ‘payment before deliv-

ery’. When that proves impossible, he will try to get

the buyer to make a down payment, one that is large

enough to keep the buyer from getting the product

elsewhere and canceling the order. This negotiation

depends on the seller’s knowledge about the buyer’s

preferences, so about p

b

. When the buyer is unwilling

to make any down payment, the seller may consider

the services of a third party, like a carrier or Escrow.

How much he is willing to pay for such services de-

pends on the value of the transaction for the seller:

how badly does he need the business? For now as-

sume that both the scenarios ‘cash on delivery’ and

Escrow guarantee the desired outcome. In practice,

an Escrow is probably more certain. We also ignore

for now the problem whether to trust the third party.

Seller’s expected value:

Scenario 4: v

s

− f ,

where f represents the carrier’s fixed fee.

Scenario 5: v

s

− ev

s

,

where e represents the Escrow fee %.

The ranking of Scenario 4 and 5 relative to each other

and to Scenario 1, 2 and 3 depends on v

s

, p

b

,a, f and

e. Now suppose v

s

= 1.0, p

b

= 0.6, a = 0.5, f = 0.05

and e = 0.1. In that case: pay before delivery (1)

> cash on delivery (0.95) > Escrow (0.9) > down

payment (0.8) > deliver before paying (0.6), from the

seller’s point of view.

We can make a similar calculation for the buyer.

Let p

s

be the buyer’s estimate of the likelihood that

the seller will deliver, without any control measure.

Assume the seller has a reputation to loose, so p

s

is

relatively high: 0.9. Similarly v

b

is the value of the

goods for the buyer. The price is agreed beforehand,

Figure 4: Delivery and payment scenarios with third parties.

rier who delivers the goods. The buyer can inspect

the goods before paying, reducing her risks. The car-

rier acts as a payment guarantee, reducing the risks

for the seller. This ‘cash collection’ can be seen as an

additional service. In this version, the service is paid

for by the seller. Here we assume the seller will trust

the carrier. In practice, the seller will often take ad-

ditional measures to control the carrier. Think of an

obligatory receipt signed by the buyer.

5. Escrow. Participants hire a trusted third party (the

Escrow) to ensure delivery and payment. First the

buyer pays the agreed sum to the Escrow. The Escrow

notifies the seller that payment has arrived. The seller

subsequently delivers the goods. Now the buyer no-

tifies the Escrow of delivery, and thereby releases the

payment, with a certain percentage deducted as a fee.

The Escrow service may be termed ‘assurance’.

Now we will compare the scenarios. We start from

the point of view of the seller. Suppose p

b

represents

the seller’s estimate of the likelihood that the buyer

will pay beforehand, with 0 < p

b

< 1. This repre-

sents the initial trust of the seller in the buyer. When

buyers are from a trustworthy community p

b

will be

relatively high, for example 0.6. But on the internet,

p

b

could be as low as 0.3. Suppose furthermore that

the seller’s value for the goods is v

s

, with v

s

> 0, and

that the down payment fraction is a, with 0 < a < 1.

Seller’s expected value:

S1: v

s

, the agreed price

S2: p

b

v

s

, where p

b

is the initial trust

S3: av

s

+ p

b

(1 − a)v

s

, for 1st and 2nd payment.

S4: v

s

− f , where f is the carrier’s fixed fee.

S5: v

s

− ev

s

, where e is the Escrow fee %.

Regardless of v

s

, p

b

and a, we have the following

ranking: S1 > S3 > S2. So when entering negotia-

tions, the seller will prefer ‘payment before delivery’.

When that proves impossible, he will try to get the

buyer to make a down payment. When the buyer is

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

316

unwilling to make any down payment, the seller may

consider the services of a third party, like a carrier

or Escrow. We assume that S4 and S5 guarantee the

desired outcome. In practice, an Escrow is probably

more certain, but also more expensive. The ranking

for S4 and S5 depends on the values for v

s

, p

b

,a, f

and e. Suppose v

s

= 1.0, p

b

= 0.6,a = 0.5, f = 0.05

and e = 0.1. In that case: S1 (1) > S4 (0.95) > S5

(0.9) > S3 (0.8) > S2 (0.6).

We can make a similar calculation for the buyer.

Let p

s

be the buyer’s initial trust in the seller. Assume

the seller has a reputation to loose, so p

s

is 0.9. The

price is agreed beforehand, so the buyer’s value v

b

=

v

s

. The other values remain the same.

Buyer’s expected value:

S1: p

s

v

b

S2: v

b

= 1,

S3: v

b

− (1 − p

s

)av

b

S4: v

b

= 1

S5: v

b

= 1.

We get the following (partial) ranking for the buyer:

{S2 (1), S4 (1), S5 (1)} > S3 (0.95) > S1 (0.9).

Clearly, the first choices do not match. The second

choices are closer. What decides the outcome of such

a negotiation? Until now we have only made assump-

tions about trust. But some scenarios will never be

the outcome of a negotiation, given the relative domi-

nance of players on the market. Suppose that there are

many sellers, who compete ferociously. Buyers have

a choice, so they can set the trade conditions. In such

a market, the cash for delivery scenario is more likely.

When there are few sellers, the seller can set the trade

conditions. In such cases a down payment scenario is

more likely. This kind of setting is traditionally an-

alyzed with game theoretic techniques. For example

(Hu et al., 2004) calculate the optimal fee for an Es-

crow service. Here we do not need full-blown game

theory. Crucial is that the assumptions are derived

from the scenario and market conditions.

4 VALUE MODELS AND RISK

In this section we describe how to re-interpret value

transfers under risk. The general idea is to label value

transfers with a probability. To reason with probabili-

ties one often has to make the assumption that they are

independent. However, value transfers are usually de-

pendent, because of the principle of reciprocity and

the dependency paths. Reciprocity means that one

transfer may only take place provided that the other

transfer has also taken or will also take place, and

vice versa. This is modeled as a mutual conditional

probability. For example, the mutual dependency of

payment on delivery in Figure 2 should ideally come

out as follows: P(pay|deliver) = P(deliver|pay) = 1

and P(pay|¬deliver) = P(deliver|¬pay) = 0.

In practice, also control measures are faulty.

How much investment in controls is acceptable?

By combining the two variables we get four pos-

sible outcomes, which can be ordered according

to their relative acceptability. In general, stake

holders tend to prefer a deal to no deal, and pre-

fer no deal to a violation of the principle of reci-

procity: (pay ∧ deliver) > (¬pay ∧ ¬deliver) >

{(pay ∧ ¬deliver),(¬pay ∧ deliver)}.

The probability that a complete transaction will

occur, is a summation of the probabilities for each

of the execution paths made possible by the coordi-

nation model. We must realize that – by definition

– these probabilities are not independent, we can-

not simply add or multiply the probabilities. Instead

we should use conditional probabilities, using Bayes’

rule: P(a|b) = P(b|a)P(a)/P(b).

Interestingly, in e3-value dependency paths are

defined as directed acyclic graphs, which model the

dependencies between events: one value transfer may

only occur provided another value transfer has oc-

curred. We suggest to use these dependency paths

to derive a Bayesian Network. Formally, a Bayesian

Network is also a directed acyclic graph, where nodes

correspond to events, and links represent causal de-

pendencies between events (Pearl, 1986). Uncon-

nected nodes are considered to be independent. This

reduces the space of possible combinations to con-

sider. Attached to each node is a conditional prob-

ability table, which gives the relative strength of the

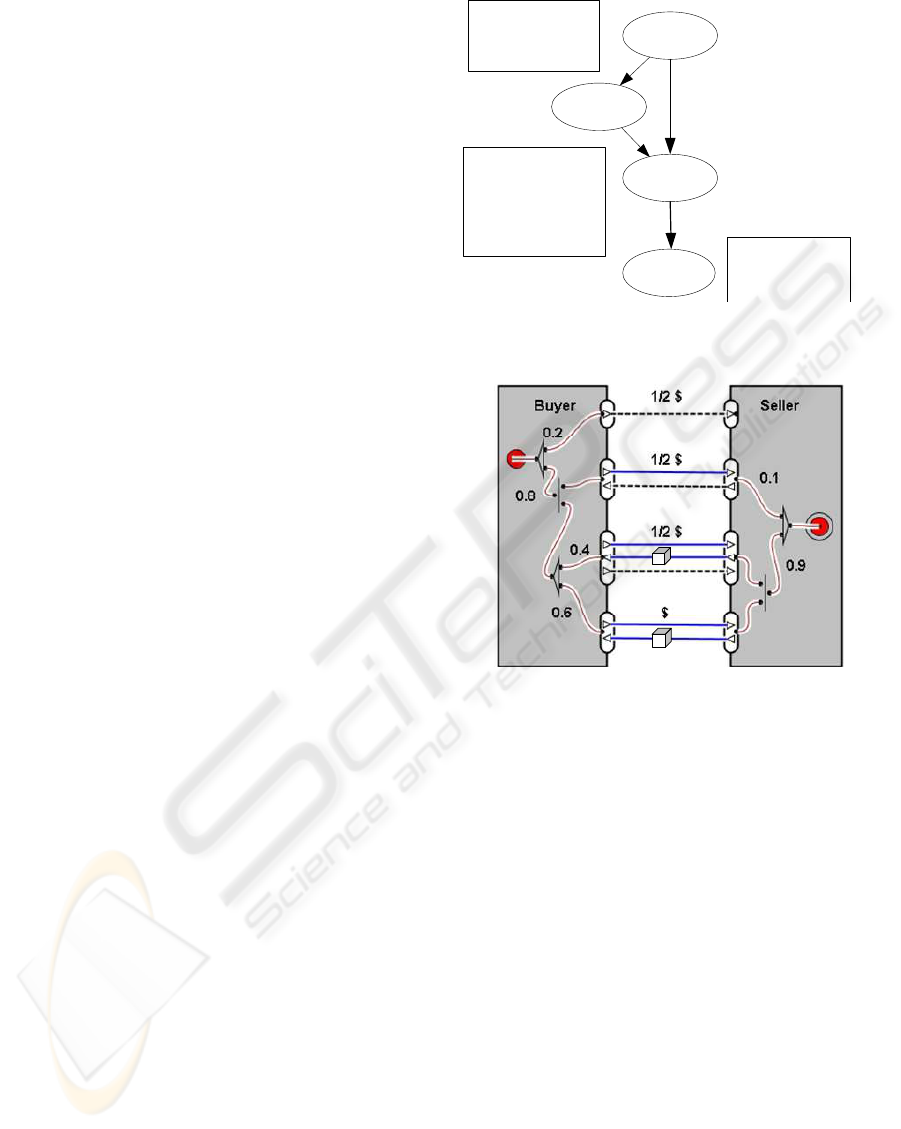

dependency (Figure 5).

Where do we get the data for ‘filling’ the condi-

tional probability tables? Well, businesses can mon-

itor the business partners and make risk estimates

based on historical experience. However, when a

new business model is set up, no such data is usu-

ally available. This need not be a problem. The point

of the example in Section 3 was to show that con-

ditional probabilities can in fact be estimated, given

general assumptions about participants and market

conditions. Think of assumptions like: ‘buyer wants

goods’, ‘seller has a reputation to loose’. In addition,

we need the relative strength of the control measures

in the coordination model, but such estimates should

be available during the design phase.

Starting from an e3-value model we can systemat-

ically explore transaction risks, using the dependency

paths, assumptions about participants, and the under-

lying coordination models as a guideline. The method

can be summarized as follows.

1. Start with an ideal value model.

RISK ANALYSIS FOR INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROLS

317

2. Start with the consumer need. Follow the depen-

dency path to the boundary element. Generate the

skeleton of a Bayesian network, using the value

model and dependency path as a guideline.

3. For each value transaction, generate a choice-fork

with two (or more) options:

– agent a goes first, followed by agent b,

– agent b goes first, followed by agent a,

– either a or b splits the value transfer,

– either a or b makes use of a third party.

4. Evaluate the value and likelihood of each of these

‘forks’ given existing agreements about control

measures in the coordination model, and general

assumptions about the domain. Now set risk =

value × likelihood.

5. To get the risk of a scenario, sum the risk over all

choice-forks.

To illustrate the method, we consider the example of

down payment (S3). First, we assume participants

agree on the down payment interaction protocol. Sec-

ond, we split the value transfer, and follow the steps

in the coordination model (Figure 3), adding non-

payment and non-delivery explicitly as events. This

would produce a game-tree, with the pay-offs (im-

pact) and likelihoods for each agent based on the as-

sumption from Section 3.

Instead of a game-tree, we can also immediately

generate the underlying Bayesian network, as we have

done here (Figure 5). The Bayesian network shows

that the conditional probabilities are very simple: here

they are only based on initial trust, and on the out-

come of the previous step in the interaction protocol.

We believe this limited complexity is a general prop-

erty of the e-commerce domain. Otherwise, the ef-

fects of interaction protocols could not be explained

to practitioners. In the last step, the trust of the seller

in the buyer (p

b

) is 0.6 without control measures, see

the argumentation in Section 3. Similarly, the initial

trust of the buyer in the seller (p

s

) is 0.9, which de-

termines the second step. There is also a chance that,

even after agreeing on the protocol, the buyer does

not want to go along with the deal after all, say 0.2.

In that case, the seller runs only a little risk, because

no goods are being shipped.

Finally, to link these probability estimates to the

impact of the various events, we can put the Bayesian

Network as it were ‘on top of’ the e3-control model.

This produces a diagram as in Figure 6. In this model,

we see the usual dependency paths of e3-value and

e3-control, but now annotated with their relative like-

lihoods. Both the likelihood and impact of the various

‘negative events’ (buyer does not pay first instalment,

seller does not deliver, buyer does not pay the second

Buyer

pays 1st

Agree on

downpayment

Seller

delivers

Buyer

pays 2nd

B pays 1st

Agr down T F

T 0.8 0.2

F 0.0 1.0

B pays Agr S delivers

1st, down T F

T T 0.9 0.1

T F 0.0 1.0

F T 0.0 1.0

F F 0.0 1.0

B pays 2nd

S delivers T F

T 0.6 0.4

F 0.0 1.0

Figure 6: Bayesian Network for Scenario 3 down payment,

with conditional probability tables

difference is that in a game-tree the positive and neg-

ative outcomes of an event are modeled as separate

events; in Bayesian networks these events become a

single node. In an interactive domain, we find that a

game-tree representation is closer to the UML inter-

action diagram, so first deriving a game-tree makes

deriving the Bayesian network conceptually easier.

The Bayesian network shows that the conditional

probabilities are very simple: here they are only based

on initial trust, and on the outcome of the previ-

ous step in the interaction protocol. We believe this

limited complexity is a general property of the e-

commerce domain. Otherwise, the effects of interac-

tion protocols could not be explained to practitioners.

In the last step, the trust of the seller in the buyer (p

b

)

is 0.6 without control measures, see the argumenta-

tion in Section 3.2. Similarly, the initial trust of the

buyer in the seller (p

s

) is 0.9, which determines the

second step. There is also a chance that, even after

agreeing on the protocol, the buyer does not want to

go along with the deal after all, say 0.2. In that case,

the seller runs only a little risk, because no goods are

being shipped, so there is no lost value.

4.2 Bayesian e3-control Models

Finally, to link these probability estimates to the im-

pact of the various events, we can put the Bayesian

Network as it were ‘on top of’ the e3-control model.

This produces a diagram as in Figure 7. In this model,

we see the usual dependency paths of e3-value and

e3-control, but now annotated with their relative like-

lihoods. Both the likelihood and impact of the various

‘negative events’ (buyer does not pay first instalment,

seller does not deliver, buyer does not pay the second

instalment) can now be estimated. In other words, the

dashed lines, which until now only indicated a control

problem, have been given a proper semantics. The

Figure 7: e3-control model with likelihood estimates for

scenario 3 down payment

meaning of a ‘sub-ideal’ dashed line, like that of an

‘ideal’ value transfer, is the relative size of the risk

associated with it. This solves the second limitation

of current conceptual modeling techniques like e3-

control. Such risk estimates can be made for all pos-

sible control solutions, such as the various scenarios

discussed here. This makes it possible to compare and

prioritize the scenario’s. Given assumption about the

relative preferences of the participants, we can predict

what the most probably outcome of the negotiation

about control measures will be. This solves the first

limitation of current conceptual modeling techniques.

4.3 Research Limitations

The research reported here is – like most research in

value modeling – meant as a conceptual modeling tool

to assist human designers and analysts. The qual-

ity of the outcomes crucially depends on the quality

of the input data and assumptions. Based on a sin-

gle example, we showed that our approach is feasible.

However, we cannot say anything about scalability or

portability to other domains. Typically, tool support

becomes really necessary for complex applications, in

which a human analyst with pencil and paper would

loose track. Future research will have to point out

whether our approach would be helpful for such com-

plex applications.

5 RELATED RESEARCH

There has been a lot of interest in value modeling,

which has lead to various extensions of e3-value. One

particular line of research concerns the translation of

the relatively abstract value models to more opera-

tional process models and coordination models. Here

we mention (Derzsi et al., 2007), as well as the work

Figure 5: Bayesian Network for Scenario 3 down payment,

with conditional probability tables.

Figure 6: e3-control model with likelihood estimates for

scenario 3 down payment

instalment) can now be estimated. In other words, the

dashed lines, which until now only indicated a control

problem, have been given a proper semantics. The

meaning of a ‘sub-ideal’ dashed line, like that of an

‘ideal’ value transfer, is the relative size of the risk

associated with it. This solves the second limitation

of current conceptual modeling techniques like e3-

control. Such risk estimates can be made for all pos-

sible control solutions, such as the various scenarios

discussed here. This makes it possible to compare and

prioritize the scenario’s. Given assumption about the

relative preferences of the participants, we can predict

what the most probably outcome of the negotiation

about control measures will be. This solves the first

limitation of current conceptual modeling techniques.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Governance and control issues of a network organiza-

tion, determine the design of inter-organizational sys-

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

318

tems in a business relation. There are various concep-

tual modeling tools for network organizations. Some

model the transfer of objects of value between ac-

tors (Gordijn and Akkermans, 2003), whereas others

model the dependencies between goals of actors (Yu,

1997). In this paper we extend one of these methods,

namely e3-control (Kartseva et al., 2005), with risks.

Risk estimates are needed to make informed decisions

about implementation of a control measure. A rep-

resentation of the relative effectiveness of alternative

control scenarios should facilitate the negotiation pro-

cess between network participants.

We propose to replace the meaning of a value

transfer by the expected value: the probability of the

value transfer succeeding, multiplied by the value it-

self. The risk then becomes the probability of the

value transfer not succeeding, multiplied by the miss-

ing value. Using an example of different interaction

protocols in an e-commerce setting, we have argued

that it is feasible to make estimates of such probabil-

ities, based on general assumptions about the partici-

pants and the domain.

Moreover, we present a systematic method for

generating a Bayesian Network, based on the value

model and the execution paths allowed by the under-

lying coordination model. The Bayesian network pro-

vides conditional probabilities for each of the value

transfers or dependency paths. The example shows

that reasonable conditional probabilities can in fact be

estimated, based on available design knowledge and

general assumptions.

Extending value models with probabilities solves

two limitations of current conceptual modeling tools

for dealing with governance and control. First, calcu-

lating the net expected value for each scenario, which

includes the probability of lost value, provides a nice

measure for prioritizing or selecting control scenar-

ios. Second, sub-ideal value transfers (dashed arrows)

which represent a control problem, are now provided

with a proper semantics. The risk exposure is exactly

the meaning of a sub-ideal value transfer.

There is some related research. Asnar et al use an

extension of TROPOS with risk assessment, to com-

pare alternative business solutions in a network orga-

nization (Asnar et al., 2008). Their work is similar

to us, because it uses dependencies to model the net-

work. However, they cannot express the impact of a

control problem in terms of the lost value.

Our research has limitations. We showed that our

approach is feasible using an example, but we cannot

say much about scalability or portability to other do-

mains. Tool support only becomes necessary for com-

plex applications. Future research will have to point

out whether our approach is helpful for large cases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Vera Kartseva and Yao-Hua

Tan for their contributions.

REFERENCES

Asnar, Y., Moretti, R., Sebastianis, M., and Zannone, N.

(2008). Risk as dependability metrics for the evalua-

tion of business solutions: A model-driven approach.

In Agent-Oriented Software Engineering VII (ARES

2008), pages 1240–1247. Springer Verlag.

Bons, R. W. H., Lee, R. M., and Wagenaar, R. W. (1998).

Designing trustworthy interorganizational trade pro-

cedures for open electronic commerce. International

Journal of Electronic Commerce, 2(3):61–83.

Gambetta, D. (1988). Trust, chapter Can we trust trust?,

pages 213–237. Basil Blackwell, New York.

Gordijn, J. and Akkermans, J. (2003). Value-based require-

ments engineering: Exploring innovative e-commerce

ideas. Requirements Engineering, 8(2):114–134.

Gordijn, J., Yu, E., and van der Raadt, B. (2006). E-service

design using i* and e3-value modeling. IEEE Soft-

ware, 23(3):26–33.

Hu, X., Lin, Z., Whinston, A., and Zhang, H. (2004). Hope

or hype: On the viability of Escrow services as trusted

third parties in online auction environments. Informa-

tion Systems Research, 15(3):236–249.

Kartseva, V. (2008). Designing Controls for Network

Organization: A Value-Based Approach. PhD

thesis, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Available at

http://docs.e3value.com/bibtex/pdf/Kartseva2008.pdf.

Kartseva, V., Gordijn, J., and Tan, Y.-H. (2005). Towards

a modelling tool for designing control mechanisms in

network organisations. International Journal of Elec-

tronic Commerce, 10(2):57–84.

Mylopoulos, J., Borgida, A., and Yu, E. (1997). Repre-

senting software engineering knowledge. Automated

Software Engineering, 4(3):291–317.

Pearl, J. (1986). Fusion, propagation, and structuring in be-

lief networks. Artificial Intelligence, 29(3):241–288.

Romney, M. and Steinbart, P. (2006). Accounting Informa-

tion Systems, 10e. Prentice Hall, NJ.

Tapscott, D., Lowy, A., and Ticoll, D. (2000). Harnessing

the Power of Business Webs. Harvard Business School

Press, Boston, MA.

Weigand, H. and de Moor, A. (2003). Workflow analysis

with communication norms. Data and Knowledge En-

gineering, 47(3):349–369.

Wieringa, R. (2008). Operational business-it alignment in

value webs. In Kaschek, R., Kop, C., Steinberger,

C., and Fliedl, G., editors, Information Systems and

e-Business Technologies (UNISCON 2008), LNBIP 5,

pages 371–378. Springer Verlag.

RISK ANALYSIS FOR INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROLS

319

Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction cost economics: The

governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law

and Economics, 22:3–61.

Yu, E. (1997). Towards modelling and reasoning support for

early-phase requirements engineering. In Proceedings

of the 3rd IEEE International Symposium on Require-

ments Engineering (RE’1997), pages 226–235. IEEE

CS Press.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

320