FACET AND PRISM BASED MODEL FOR PEDAGOGICAL

INDEXATION OF TEXTS FOR LANGUAGE LEARNING

The Consequences of the Notion of Pedagogical Context

Mathieu Loiseau, Georges Antoniadis and Claude Ponton

LIDILEM, Universit Stendhal Grenoble 3, Grenoble, France

Keywords:

Pedagogical indexation, Computer assisted language learning, Natural language processing, Modeling, Meta-

data.

Abstract:

In this article, we discuss the problem of pedagogical indexation of texts for language learning and address it

under the scope of the notion of “pedagogical context”. This prompts us to propose a new version of a model

based on a couple formed of two entities : prisms and facets.

We first evoke the importance of material selection in the task of planing a language class in order to introduce

our point of view of Yinger’s model of planing applied to language teacher’s search of texts. This is closely

intermingled with the elaboration of the notion of pedagogical context from which our model stem. This

version though in a way similar to our first attempt provides sounder notions on which to build on.

1 PEDAGOGICAL INDEXATION

1.1 The MIRTO Project

The MIRTO project, started in 2001, stemmed from

the observation of various recurrent issues in Com-

puter Assisted Language Learning (CALL) systems:

rigidity, inability to adapt the learning sequences to

the learners and the necessary adaptation of teachers

who are not provided with means to manipulate con-

cepts pertaining to their field of expertise (language

didactics) (Antoniadis et al., 2004). The aim of Multi-

apprentissages Interactifs par des Recherches sur des

Textes et l’Oral (MIRTO) was to promote the use of

Natural Language Processing (NLP) in order to ad-

dress those problems by adding an abstraction layer

between the user and the material he/she manipulates.

Indeed, they consider that to allow teachers to formu-

late their problems in didactics relevant terms, lan-

guage should not be handled as character sequences

but as a system of forms and concepts (Antoniadis

et al., 2005). In order to do so, MIRTO proposes to

separate treatments (e.g. gap-filling exercise genera-

tion script) and the data on which they are to be ap-

plied (a text in this case).

1.2 Definition and Objectives

This made evident the need for a text base, which,

for consistency’s sake, would have to allow user’s to

perform language teaching driven queries. In other

words, a subpart of the problem was the conception

of a system that could perform pedagogical indexa-

tion of texts. In this work we defined pedagogical in-

dexation as “an indexation performed according to a

documentary language that allows users to query for

objects in order to use them for teaching” (Loiseau,

2009). Considering the aforementioned context, we

are therefore working towards pedagogical indexation

of texts for language learning.

Indeed, a study of the literature concerning the

most often used language teaching methods and a

series of interviews with some language teachers

prompted us not only to consider this problem in the

context of the future use of the text in a CALL activ-

ity, but to try to consider the problem globally: few

of the teachers we had interviewed were really com-

puter savvy, all the same, they all underlined the im-

portance of text search in their practices. We later got

confirmation of this nature of things by a larger scale

study, which established text search as a common task

in language teaching (Loiseau, 2009).

Having modified the scope of our work – with-

out completely cutting ties with MIRTO, for integra-

tion remained a perspective – into the conception of

413

Loiseau M., Antoniadis G. and Ponton C. (2010).

FACET AND PRISM BASED MODEL FOR PEDAGOGICAL INDEXATION OF TEXTS FOR LANGUAGE LEARNING - The Consequences of the Notion

of Pedagogical Context.

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Software and Data Technologies, pages 413-422

DOI: 10.5220/0003015504130422

Copyright

c

SciTePress

a model for pedagogical indexation of texts for lan-

guage teaching, we started to consider the existing

means to achieve it.

1.3 Learning Resource Description

Standards

A wide array of research tackles the definition and

use of learning resource description standards. The

principal standards we analyzed were Learning Ob-

ject Metadata (LOM) (IEEE, 2002), Sharable Con-

tent Object Reference Model (SCORM) (SCORM,

2006) and some teaching oriented application pro-

files of the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI)

(GEM, 2004; edna, 2006). As for providing a so-

lution to our problem, all the standards we stud-

ied came with the same flaws, most of which come

from the fact that these standards try to integrate in

the same model, entities of very different conceptual

level: the ressources used to set up activities (low ag-

gregation level in the LOM terminology) and the ac-

tivities themselves (higher aggregation level) (Pernin,

2006). Balatsoukas et al. take the analysis a little bit

further in pointing out that the lower the aggregation

level of the learning object the broader its spectrum

(i.e. the range of activities that can be performed with

it) (Balatsoukas et al., 2008). Indeed, in the particu-

lar case of texts (raw resources), the descriptors pro-

vided by the standards seem, at best, difficult to use:

how does one assign a “Description” (“Comments on

how this learning object is to be used” (IEEE, 2002))

when the resource potentially could be used in differ-

ent contexts.

The approach advocated by Recker & Wiley pro-

poses to treat differently what they call intrinsic

(“derivable by simply having the resource at hand”)

and extrinsic properties (which “describe the context

in which the resource is used”) (Recker & Wiley,

2001). All the same, their analysis cannot be directly

transposed to our problem, for their aim is to provide

a collaborative resource description system in which

authoritative and non-authoritative annotation coex-

ist. On the other hand our aim is, in the first place,

to provide a model that would allow a system to auto-

mate as much as possible the pedagogical indexation

of texts. User annotation is, in this context, more a

potential extension of the system than a core feature.

There was therefore at this point no clear cut direction

in which to go: the pedagogical properties seemed to

constitute extrinsic properties for the raw resources

that are texts, thus potentially discarding educational

metadata as a solution. We therefore decided to resort

to an empirical study to confirm this hypothesis and

get a grasp of teachers practices regarding text search.

2 PEDAGOGICAL CONTEXT

2.1 Empirical Study

Our empirical study took the form of a survey, which

built on a series of interview and an exploration of

the literature, part of which we have just summed up

above. Beyond the confirmation of the hypothesis of

the multiple uses texts can have in language teaching,

we aimed at obtaining a first look into the process of

text search. We meant our point of view to be as gen-

eral as can be, in the hope to extract invariants, that

would remain unaffected by variables such as the lan-

guage taught, the country in which it is taught or to

whom. The study was mostly filled online, but also

in paper form, both medium adding up to 130 testi-

monies. Beside confirming unequivocally that texts

can be used in various language teaching situations

1

,

the survey allowed us to extract a (non necessarily ex-

haustive) list of four practices that lead to texts being

used in language learning: search for a text to use

in a precise activity, writing the text, text encounter

during personal readings and texts on a syllabus (of

any form). We will focus here on the provenance that

is closest to the role of a pedagogically indexed text

base, i.e. the search for a text in order to use it in a

specific activity, which also happens to be the most

widely represented practice (concerning nearly 97%

of the teachers answering the survey).

2.2 Adaptation of Yinger’s Model

To describe the task of searching for a text for a

given activity we resorted to using Yinger’s model

of planification (Yinger, 1978) or more precisely part

of it. Yinger defines planing as a three stage pro-

cess: problem finding, problem formulation/solution

and finally implementation, evaluation, routinization

(Yinger, 1978). In our task, the problem is already

found (the teacher has an activity in mind) and the

search is supposed to provide a text to actually use

in class and thus precedes implementation. We fo-

cus here on the problem formulation/solution, which

according to Yinger is an “helicoidal” repetition of

three phases: elaboration, investigation and adapta-

tion (Yinger, 1978), which we adapt to our problem

under the labels selection, evaluation and transforma-

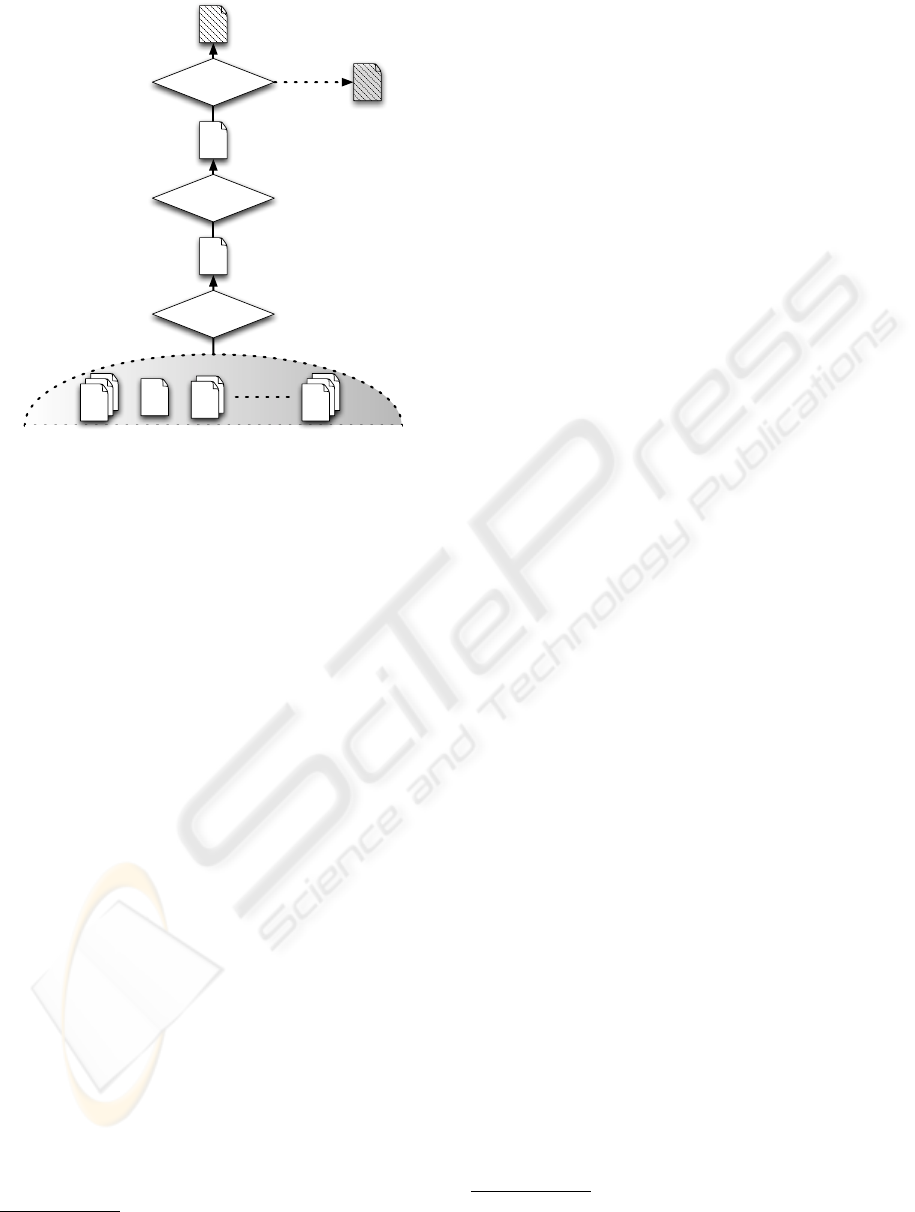

tion (cf. figure 1 p. 3) (Loiseau, 2009).

The dashed semi-ovoid at the bottom of figure1

contains a set of texts the teacher has access to. The

1

97,3% of the teachers who answered the question de-

clare they consider that a given text can be used with vari-

ous goals in different contexts and 94,5% of them (92% of

our the sample) declare having done so.

ICSOFT 2010 - 5th International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

414

Transformation

Evaluation

Selection

+ Evaluated properties

+ Projected properties

Figure 1: Yinger’s model adapted to text search.

intensity of the gray inside the form represent to

which extent they are pedagogically “connoted”. For

instance a text taken straight from a newspaper and

that has never been used in teaching (to the knowl-

edge of the teacher) is not connoted, whereas a text

recommended by peers or found inside a textbook has

some sort of pedagogical connotation. The aim is not

to evaluate this “connotation” or even theorize it, but

to acknowledge that the teacher can resort to sources

with different statuses.

The selection phase consists in the teacher relying

on his necessary preconceptions

2

projecting onto the

text properties linked in a way or another to the activ-

ity they are planning. An example of such a behav-

ior would be a teacher choosing an author based on

some properties they attribute to their writing: “Roald

Dahl, [...] all his short stories are packed with these

verbs [...] for emotion and gestures [...], that in French

[require] a whole phrase [...].” (testimony from our

study).

Once the text is selected based on the properties

that the teacher has attributed a priori to the text, the

text is actually in the hands of the teacher (or virtu-

ally so) for the first time in this planning sequence

and they can now attribute a new set of properties to

the text. They are no longer projected properties, they

constitute the teacher’s actual perspective on the re-

source based on the activity they want to set up with

it. This set of properties can confirm or invalidate the

ones that have been assigned during the first phase

or concern totally different aspect of the text. For in-

2

Without preconceptions this phase would consist in a

random selection of texts.

stance, it is completely imaginable that the teacher we

quoted above should confirm her hypothesis, but con-

clude that the short story can turn out to be difficult

for her learners, which brings us to the last phase: tak-

ing action upon the evaluated properties. The action

transforms the text status-wise, there are three alter-

natives:

• the text is assigned a use context corresponding

the teacher’s current search and is transformed

into actual teaching material (solid arrow in fig-

ure 1);

• the text, though considered unfit for this particular

activity, is deemed useable in another context and

can be kept for future use in a personal repository:

it is transformed into potential teaching material

(dotted arrow in figure 1);

• the text is not relevant from the teacher’s point of

view and is just discarded (not represented).

2.3 First Definition

The description of these three phases allowed us to

precise the role of a pedagogically indexed text base:

it is meant to assist the teacher in the selection phase

and possibly allow him to perform it according to

less instinctive criteria when applicable (for example

concerning the linguistic content of the text), but it

also allowed us to introduce the notion of Pedagogi-

cal Context (PC)

3

as: “set of features which describe

the teaching situation” (Loiseau, 2009). This notion

is especially useful in order to describe the process of

text search and its integration in a learning sequence

for the various iterations of the above scenario corre-

spond to a gradual definition of the PC: the material is

a component of the teaching situation (Charlier, 1989)

thus influencing it and at the same time its choice is

influence by the other components of the PC since the

search is performed for a given activity. In order to

achieve pedagogical indexation of texts for language

learning, it seems necessary to be able to take into ac-

count the PC, which means studying the link between

components of the PC and the actual properties of the

text.

3 PC AS AN INFLUENCE CAST

ON TEXT PROPERTIES

Among our objectives with our second survey was

trying to establish relations between properties of the

3

In order to avoid exceedingly numerous repetitions, we

will either refer to it using “PC” or its complete form “Ped-

agogical Context”.

FACET AND PRISM BASED MODEL FOR PEDAGOGICAL INDEXATION OF TEXTS FOR LANGUAGE

LEARNING - The Consequences of the Notion of Pedagogical Context

415

PC and properties of the text. We cross-examined:

• the activity type (gap-filling exercise – 3 types –,

comprehension activity, introduction of new no-

tions – vocabulary or syntax –) with the size of

text, the number of representative elements of a

notion (if the notion is the preterit this will be

the number of preterit conjugated verbs of the

text, and the tolerance to newness (vocabulary and

grammar-wise);

• the learners’ first language and tolerance to new-

ness ;

• the learners’ level and tolerance to newness.

The length of the text and the number of represen-

tative elements were numerical variables and asked

for each activity type. In this case, the tolerance to

newness was evaluated using two separate categori-

cal variables, one concerning new vocabulary (other

than the object of the lesson) and the other concern-

ing new grammatical structures (other than the object

of the lesson). Both variables could take their values

between “proscribed”, “tolerated” and “sought”. For

each activity type used, we asked the teachers to rate

their tolerance to newness using this scale for both

variables.

When crossed with the learners’ level and first lan-

guage, the tolerance to newness was also the object of

a closed-ended question. These questions allow the

teacher to state that the criteria is not relevant or can

decide not to answer. The other two possibilities de-

pended on the question and do not distinguish vocab-

ulary and grammar:

• first language: the more similar the mother tongue

and the learned language, [the more/the less] one

will accept unknown grammatical structures or

vocabulary;

• level: the higher the level, [the more/the less] one

will accept unknown grammatical structures or

vocabulary.

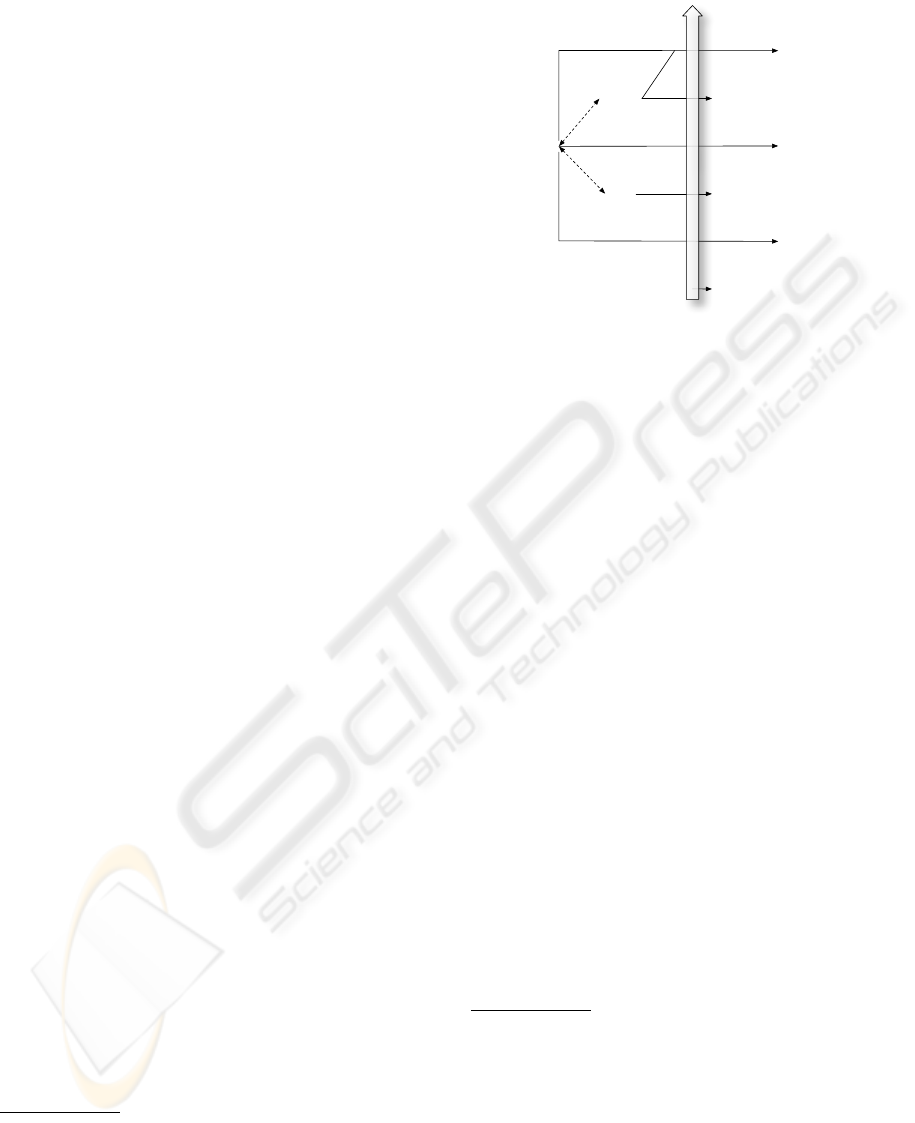

The results can be summed up by figure 2

4

.

Properties such as the length of a given text are to-

tally independent from the Pedagogical Context and

thus do not need it to be computed, but our study

showed that the activity type had an effect on text

length

5

, which means that depending on the activity

type, teachers will be looking for texts of different

4

Due to room restrictions we cannot include detailed

statistics in this paper, they are available in section 5.3

(pp. 231–245) of (Loiseau, 2009) though.

5

ANOVA: F(143) = 3, 362 ; p <, 01. Post-hoc tests are

significant when comparing “comprehension activity” with

the various forms of “gap-filling exercises” (Loiseau, 2009).

Text

Properties

Pedagogical

Context

Text length

Goals

Audience :

- Level

- L1

Activity

Decision

Number of representative

elements

Unknown vocabulary

and structures

Decision

Decision

System

text

description

Sequence for a given text

Figure 2: Influence of the pedagogical context on the attri-

bution of text properties.

lengths. A text property such as the number of repre-

sentative elements of a notion obviously depends on

the notion, which in turn is a direct consequence of the

pedagogical goals of the teachers. Likewise, the num-

ber of representative elements of a notion that is con-

sidered appropriate by the teacher will depend on the

activity type (e.g. 4 or 5 occurrences might be enough

to introduce a notion, whereas to practice it under the

form of a gap-filling exercise teachers seek an aver-

age of 11 occurrences)

6

. Finally, if the amount of un-

known vocabulary/structures is a property of the text,

it cannot be evaluated unless we link it with the au-

dience with whom the activity is going to be used. It

directly depends on the level of the students, which is

also used differently afterwards to take a decision on

whether or not to use the text: the higher the students’

level the more tolerant the teachers will be regarding

the presence of new vocabulary or structures (other

than the object of the lesson). The activity type

7

and

the proximity between the learners’ language and the

one that is taught also seem to have a significant effect

on the tolerance to “newness”

8

.

The various tests we have performed on the above

series of variables tend to show that the Pedagog-

ical Context indeed influences text properties. We

lack data to precisely characterize the relations be-

6

ANOVA: F(127) = 4, 739 ; p <, 005. Post-hoc tests are

significant when comparing “introduction of a new notion”

with “comprehension gap-filling exercise” and “introduc-

tion of a new syntactic notion” with “form aimed gap-filling

exercises” (Loiseau, 2009).

7

χ

2

(10) = 32, 2 ; p <, 001 (Loiseau, 2009).

8

81.3% of teachers taking into account their learners

first language considered that closer languages allow more

tolerance (Loiseau, 2009) and 71.4% consider that the

higher the level of the learners the more unknown vocab-

ulary/structures they will accept (Loiseau, 2009).

ICSOFT 2010 - 5th International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

416

tween text properties and the PC, but we have been

able to demonstrate their existence. The fragmen-

tary knowledge we have come to gather have yet al-

lowed us to explore examples of ways to take into ac-

count these concurrent influences that the Pedagogi-

cal Context has on text properties or on the way to

act upon them. Interestingly, they all follow the same

pattern, the properties which depend on the PC repre-

sent a sort of point of view of the text reflecting the

problem of the teacher in his search. The Pedagogical

Context, despite still representing the same entities in

the real world, has become, thanks to a switch of fo-

cus, “a paradigm casting its influence on the texts’

properties”.

4 PRISM-FACET BASED MODEL

The following model aims at taking into account the

role of the Pedagogical Context in the evaluation of

text properties, in order to propose help to the user

in his selection task. It is a second version of the

model which has been introduced in (Loiseau et al.,

2008). We will first describe this new version of the

model, before we conclude by explaining the main

differences between the two versions.

4.1 Recursive Definitions

The model is articulated around a couple of two indis-

sociable notions: prism and facet. The prism insures

that the properties are coherent in the way they are

computed: “a prism is a mechanism – computerizable

or not – associated to a property defined considering

the texts’ later exploitation in teaching, which allows

to assign a value to this property for all text depending

on a given pedagogical context”

9

.

This definition allows us to highlight the link with

pedagogical indexation: the definition of the prism

depends on the needs of the teachers. This definition

revolves around the difference between the concep-

tual level of the properties (class of properties) and

their value (after instantiation). It is the essence of the

prism which is the procedure which allows to make

the transition from the first to the latter, when apply-

ing the concept to a given object (a text).

This leads us to the formalization of the property

and like the prism depends on the property it is meant

to describe depends on its alter ego: “a text facet is a

property of the text, which was defined with a view to

its pedagogical exploitation in laguage teaching and

9

Translation of the definitions page 257 of (Loiseau,

2009).

for which an evaluation procedure can be defined and

applied to any given couple (text, PC)”

9

.

4.2 Facet and Facet-Value

Before we go on and explore the consequences of the

above definitions, we shall enter a terminological is-

sue. Like the term “property”, the word “facet” is, as

we use it, polysemic. It can, depending on the context,

designate either the concept or the attribute. For in-

stance, “parallelism” is a property (concept) which is

applicable to a certain type of object, and two planes

(for instance the ground and a shelf) can have the

property to be parallels. In the case of facets, we

might use the word to designate either the property in

its conceptual form – facet F

i

, text facet or just facet

with no other precision – or its value for a given cou-

ple (text, PC) – a given text’s facet, F

i[CP]

(T ) –.

4.3 Constant Facets

From the point of view of the task of selection, the

facet is the central entity on the conceptual level: in

the planning process, the facets represent the notions

upon which the teachers base their reasoning. A ped-

agogically indexed text base will not be able to take

into account every teacher’s individual point of view

of every facet presented to them (or not in the near

future), the usability of such a system therefore relies

on the prisms, which offer consistency through their

mechanical, systematic, nature.

Going through some of the properties represented

in figure 2 will allow us to explain further the model.

Text

T

F

author

(T)

=Андрей

Курков

P

wrdCount

P

author

F

wrdCount

(T)

=1101

Figure 3: Prism examples and values for the corresponding

facets (independent from PC).

In figure 3, we indicate two examples of facets.

The word count (F

wrdCount

), which is exactly the same

as the property in figure 2 and F

author

corresponding

to the author of the text. The diagram also presents

the values of these facet for a given text T . We intro-

duce a functional notation based on the facets, even

though strictly speaking the application that allows

the computation of the values is defined inside the

FACET AND PRISM BASED MODEL FOR PEDAGOGICAL INDEXATION OF TEXTS FOR LANGUAGE

LEARNING - The Consequences of the Notion of Pedagogical Context

417

prisms (P

wrdCount

and P

author

, here), which precise the

status of both entities:

• the prism is a tool, materializing a process;

• the facet is a concept, a text property which has a

value for every couple (text, PC).

4.4 The Pedagogical Context in the

Model

In these first examples, the Pedagogical Context does

not influence the value of the facet, which remains

constant for a given text T for any PC. The aim of

the model is to represent more complex properties. In

figure 2, the number of representative elements is an

example of such a facet. We represent it in figure 4.

In this figure, a sole prism (P

repE

t

) is shown revealing

F

repE

t

[Pretérito]

(T

1

)=0

F

repE

t

[haber* que +

inf]

(T

2

)=2

F

repE

t

[haber* que +

inf]

(T

1

)=4

F

repE

t

[Pretérito]

(T

2

)=3

Text

T

1

Text

T

2

P

repE

t

PC

2

PC

1

pretérito indefinido

haber* que + inf

Figure 4: Prism examples and corresponding facets for 4

different (text, PC) couples.

two facets for each text. Each of the two facets of T

1

and T

2

corresponds to a different Pedagogical Context

for which both text could be compared to come to a

decision. In the example of figure 4, the T

1

contains 4

occurrence of haber que structures

10

and no preterit,

while T

2

contains 2 occurrences of haber que struc-

tures and 3 occurrences of preterit. Figure 4 also rep-

resents the metaphor behind the name of prism and

facets. In this metaphor the Pedagogical Context is

a light cast on a text through a prism, thus revealing

one of its facets. Consistently with its optical counter-

part the prism divides the ray of the PC to keep only

the components (frequencies) which are necessary to

compute the value of the facet. Applied to a system

which would assist the user in its selection task, the

choice of prisms would have an expressive function:

the user would only be asked of the PC components

10

Used to express duty in Spanish: Para soar hay que

dormir (to dream, one has to sleep), Habr que resistir un

tiempo ms (One will have to go on resisting for a while).

required by the prisms selected, thus providing them

with means to describe the features of the teaching sit-

uation which are relevant for their search (figure 5).

T

PC

P

n

P

i

P

1

Figure 5: Expressive function of the prisms.

The notation introduced in figure 4 is meant to

render the difference of status that exist in the model

between the PC and the texts. This difference comes

from the function of the model, namely to provide

a framework for the implementation of a system of

pedagogical indexation of texts for language learn-

ing. When performing a given iteration of the cycle

described in 1, the PC is constant. Of course, for a

task of text search to yield a text that is actually used

in language learning, the Pedagogical Context might

evolve during the various iterations of the cycle, but

the PC will be constant inside a given selection sub-

task (for which a system is supposed to provide assis-

tance) of a given cycle. Yet, each prism is evidently

meant to be reusable from one cycle to the other and,

by definition, has to be able to compute values of its

associated facet for all PC

11

, hence the notation.

4.5 Prisms as a Mean of Selection

By definition, indexation is essentially a description

task (Bertrand et al., 1996), yet its aimed at allow-

ing users to easily spot the texts that satisfy their

needs, an objective of discrimination. In our case,

part of the discrimination task, will not be automat-

able (e.g. based on interestingness or on the ability

to give rise to a debate), the other part will mostly

rely on constraining the tolerated values of facets. We

have concluded that the better way to model that kind

11

The implementation of certain facets, such as the num-

ber of occurrences of a given type of reported speech (direct,

indirect, free indirect) would require manual intervention.

All the same a mechanism can be defined in order for a hu-

man to annotate it (making it a facet). In a system, such a

facet could be implemented on a set of texts. To make such

texts coexist in a system with not annotated texts (treating it

as a subcorpus), not applicable has to be an accepted value

of a facet for a text in a certain pedagogical context.

ICSOFT 2010 - 5th International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

418

of constraint is to integrate it inside the Pedagogical

Context and thus to take it into account in the value

of the facets. A constrained version of a facet just

add a phase to the mechanism associated to its com-

putation: after the value of the non-constrained avatar

of the facet is computed a simple test instruction can

be added, to return false if the constraint is not met

and the value computed otherwise. In the constrained

facet obtained, the expression of the constraint is part

of the Pedagogical Context. Indeed, it is relevant to

the problem of the teacher to decide, depending on

the situation they want to use the text in, to exclude

texts based on the value of facets such as its length.

We have been convinced of that when trying to

consider higher level facets. For instance, one can

imagine developing a prism which would allow to

take into account the information we have gathered in

our study regarding the activity type

12

: let F

AN

be the

facet associated to this prism. F

AN

could be a boolean

property telling whether a text is potentially suitable

for an activity. The PC components used would be

the activity type and the notion on which to work.

The treatment would rely on the facets we have called

F

wrdCount

and F

repE

t

, fixing threshold values for each

activity type (for instance a gap-filling exercise could

not be longer than n words and could not contain less

than, say, 5 occurrences of the notion. The constraint

of F

wrdCount

and F

repE

t

is directly derivable from the

PC of F

AN

, which is a clue in the direction of our so-

lution. But the decisive element is the fact that the

threshold values that could be defined based on our

study, despite lacking precision, come from teacher

declarations. They were given the possibility to con-

sider the criteria not pertinent, which means that it

is very likely that it corresponds to a conscious fea-

ture expected in the text (if not explicitly evaluated)

and thus qualify as a component of the Pedagogical

Context. We do not consider this the only solution,

but find it a consistent and practical one.

4.6 Facet vs Metadata

The notions of facet and prism allow to:

• associate the concept (facet) and its modeling,

making explicit the sense of the concept handled

by the tool (prism);

• model the influence of the Pedagogical Context on

the properties of the objects (texts).

These two characteristics distinguish facets from

metadata. According to Bourda, metadata is informa-

12

The actual implementation of such a facet would re-

quire much more experimentation: we only have declared

practices, which would lack precision.

tion on objects which can be understood by humans

and processed by software (Bourda, 2002). Both

facets and metadata are therefore meant to propose

a global point of view of an object rather than high-

light information contained in the document (for in-

stance F

repE

t

means to provide a unique value asso-

ciated to a structure, not to list all the occurrences of

the structure). This similarity in the object of both

notions is especially conspicuous for constant facets

(cf. figure 3), which could be treated with metadata.

But in the same way that constant functionals such as

f (x) → 0 are a particular case of functionals, constant

facets are only a particular case of a generic notion,

which cannot be efficiently modeled with metadata.

This can be shown with the example of F

repE

t

.

In order to implement comparable description with

metadata one would need to anticipate any possible

request made by teachers. The text “Rabbits run.”

would require a descriptor saying it contains one oc-

currence of the form “rabbits” but also one occurrence

of a form the lemma of which is “rabbit”. The text

should also be found if the teacher is looking for the

form “run”, but also if they are looking for a text con-

taining occurrence of the present simple of the verb to

run. We already have 4 descriptors indicating one oc-

currence of a given structure. But it might also be

pertinent to know that the text contains one occur-

rence of “rabbits run”, one of a form whose lemma

is “rabbit” with the verb run, one occurrence of the

form run associated to a plural subject, etc. And this

only concerns a 2 word text.

When the Pedagogical Context offers a certain va-

riety of potential values – each of which should be

associated with a value for each text – the fixedness

of metadata requires to anticipate every single one of

them, making it potentially hazardous or inefficient

as far as storage is concerned (in our example, despite

not being exhaustive, we have found 7 descriptors for

a single facet and a two word text). Facets and prisms,

by associating a property and a means to compute it

introduce flexibility and dynamicity in the description

of resources, which seem necessary to handle the no-

tion of Pedagogical Context.

5 TOWARDS IMPLEMENTATION

The example of F

repE

t

leads to considering implemen-

tation options. Indeed, in order to introduce flexibility

and to make computation of facet values possible, the

information on the text provided by F

repE

t

relies on

information of the text. The computation of values

of F

repE

t

could be handled first by performing mor-

phological analysis of the text, before using regular

FACET AND PRISM BASED MODEL FOR PEDAGOGICAL INDEXATION OF TEXTS FOR LANGUAGE

LEARNING - The Consequences of the Notion of Pedagogical Context

419

expressions on the resulting annotated version of the

text. We will refer to the information of the text added

by the first part of the process as underlying proper-

ties of the text. They are to be analyzed to provided

information on the text, namely facet values.

When implementing this sequence of treatments

in the perspective of indexing them, the addition

of underlying properties (morphological analysis for

F

repE

t

), which will be referred to as pre-processing,

should be performed once and for all, when the text

is added to the system. On the other hand, in order

to introduce the dynamicity that metadata lacks, the

computation of facet values, which we will refer to

as computation, need to be performed when the user

queries the system.

5.1 Prisms and Functions

This decomposition of the prism’s mechanism as a se-

quence of treatments decomposed into pre-processing

and computation allows us to answer the question

asked by note

11

p 6. When implementing a facet

based system, a prism mechanism can require human

pre-processing but computation needs to be fully au-

tomatable.

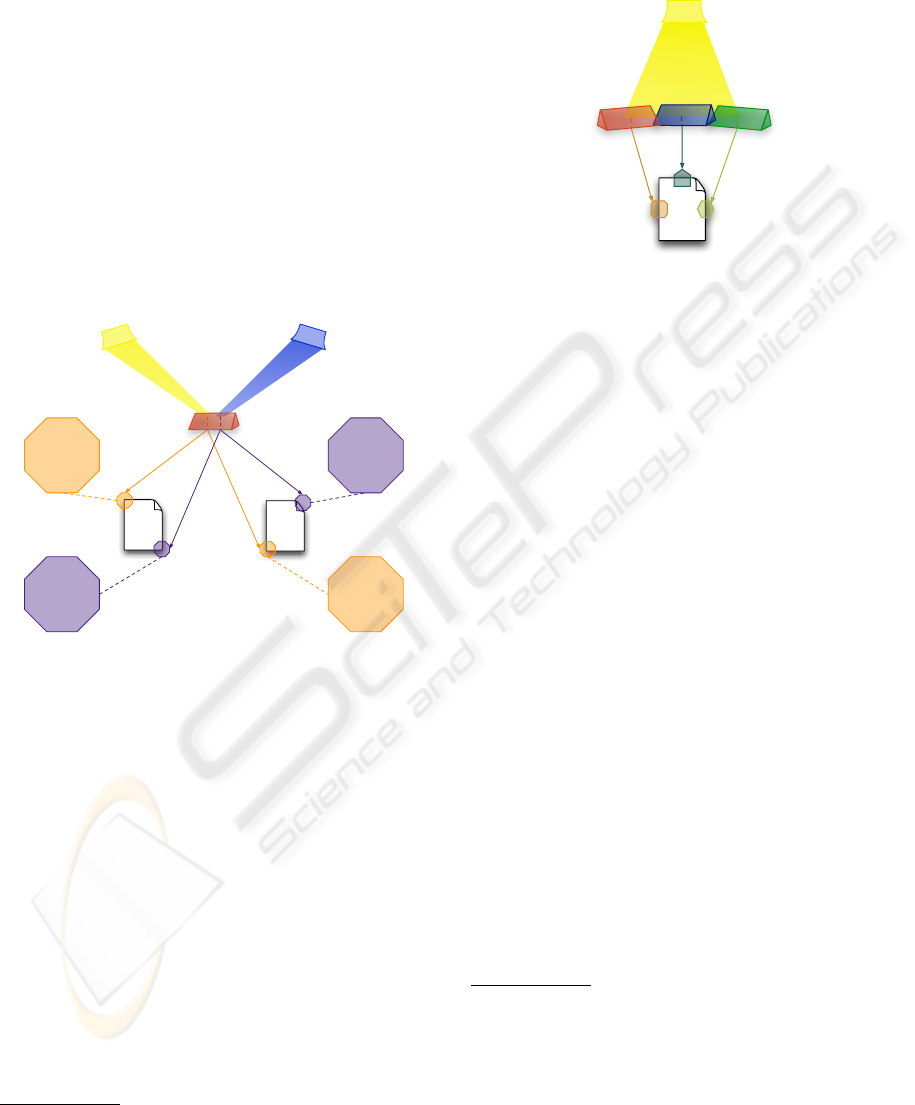

As far as implementing prisms, to provide evolu-

tivity and take advantage of already developed tools

(especially NLP procedures), we recommend reusing

the concept of function as defined in MIRTO (Anto-

niadis et al., 2004). According to this point of view

a prism is linked to a facet and composed of two se-

quences of functions: pre-processing and computa-

tion (cf. figure 6).

Fn

4

Fn

2

Fn

3

Fn

n

Fn

i

Fn

1

Interface

Coordination module

Language

teacher

Text

collection

Pre-processing

Computation

Views

FunctionsScripts

Prisms

Selection

Evaluation

Figure 6: Proposed general architecture for a facet based

system.

5.2 Views

In figure 6 prisms are not the only entity composed

of functions. As an extension of the indexation sys-

tem and a means for the user to interact with the sys-

tem we introduce the notion of views. Considering

the complexity of certain properties which intervene

in the process of searching for a text to use in lan-

guage teaching and the difficulty to achieve reliability

in NLP when moving away from the form, a realist

approach needs to acknowledge the amount of work

left to the user during the phase of evaluation. Among

other considerations, the fact that “100% reliability

is, and may stay in the future, an unattainable goal.

Therefore it is more realistic to stress on ‘assisted’

rather than ‘fully automated’ approaches” (Blanchard

et al., 2009) is at the origin of their “didactic trian-

gulation strategy”. Adapting it to our problem, views

come as a mean to assist language teacher in the eval-

uation phase. They are meant to allow the user to ac-

cess to some of the underlying information, in order

to help them in their evaluation, adopting a qualita-

tive point of view where prisms are quantitative. For

instance in figure 7.

Preterit verbs

Views

Pipepline (8)Pixies (5) 3 bears (13)

The Story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears

tasted (3)

was (2)

answered

came

explained

knocked

said

walked

went

were

Text

List

Preterit verbs

Pipepline (8)Pixies (5)

3 bears (13)

Views

The Story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears

Once upon a time, there was a little girl named

Goldilocks. She went for a walk in the forest.

Pretty soon, she came upon a house. She

knocked and, when no one answered, she

walked right in. At the table in the kitchen, there

were three bowls of porridge. Goldilocks was

hungry. She tasted the porridge from the first

bowl. "This porridge is too hot!" she explained.

So, she tasted the porridge from the second

bowl. "This porridge is too cold," she said. So,

she tasted the last bowl of porridge.

Text

List

Figure 7: Example of views linked to F

repE

t

for PC preterit.

A user looking for a text to have their learners

work a structural exercise on the preterit tense in En-

glish, might want a text with at least 7 occurrences of

the tense. They might want to make sure that the text

contains irregular verbs including “to be”. To discard

a text the list view would be sufficient and might be

more convenient than the highlighted view (see fig-

ure 7), which would offer to the teacher an in context

glimpse at the verbs, that might be preferable to make

sure that the resulting activity would not prove too

difficult (or easy) for the learners.

The notion of view has not been fully formalized

yet. The link with facets has to be specified further:

are some of the views completely independent from

ICSOFT 2010 - 5th International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

420

any facet (and thus prism), relying on their own pre-

processing or should they all be linked to a facet the

way the views in figure 7 are to F

repE

t

? Should the

ones that are linked to specific facets solely be linked

to them by their common pre-processing or should

they before all be linked to a prism ?

6 CONCLUSIONS

We introduced this model as a second version of a pre-

vious work (Loiseau et al., 2008). This new version is

not only justified by a concerned to make it clearer:

despite being similar in philosophy, it comes after

the theorization of the notion of Pedagogical Context.

Even though present in the first version of the model,

PC was roughly defined. The work on the notion has

allowed us to build on sounder basis the notions of

facet and prism, which have be subject to semanti-

cal alteration. The prism was in the first version a

global module of the system handling all processes

and which is now explicitly linked to a facet, thus un-

derlying the tight link between the two of them.

Despite its simplicity, prism P

wrdCount

exemplifies

this relation, the kind of approximation inherent to the

task at hand and the usefulness of NLP in the imple-

mentation of such a system. Depending on the capac-

ities of the pre-processing

13

the definition of the facet

can be altered (or the other way around). The word

count can be based on a list of separators between

which lie the words to be counted. But in this case the

French “chou-fleur” could be two words, while it ac-

tually designate a precise object (cauliflower)

14

. The

decision of which kind of treatment to use can come

from a didactic question: one wants to evaluate the

length of the text, in order to provide an idea of size

of the text, considering compounds as separate words

might not be a problem. But one might consider that

the word count should be as consistent with the lin-

guistic definition of word as possible. But what in-

terest teachers could actually be to consider as words

only non function words in order to get a better grasp

at the quantity of vocabulary necessary to understand

the text. On the other hand the choice of what the

facet actually means might come from purely practi-

cal reasons: the available word count function works

with no dictionary whatsoever and cannot distinguish

function words from others or even identify a com-

13

In this case the pre-processing actually could evaluate

the property, due to its independence from the PC.

14

’-’ should be a separator in French since it is added

when the verb and subject are inverted to form a question:

Dort-elle ? Oui, elle dort comme une masse. (Is she sleep-

ing? Yes she is sleeping like a log)

pound. In both, case the link between the concept be-

hind the facet and the prism should remain unaltered,

might it mean modifying the prism, the facet or both...

The meaning of view has also changed (the view

of this version of the model corresponds more or less

to the visualization of the former) leading to alter-

ation of the implementation. The questions raised in

the previous section by this extension to the evalua-

tion task are among the various implementation ques-

tions at hand. We are implementing a prototype of

this version of the model. It will undoubtedly raise

more questions, such as the definition of a framework

for prisms in order to make their integration and de-

velopment easier.

Such a definition could also lead us to consider the

problem of the system’s adaptation to its users up to

allowing them to create their own prisms and facets.

Indeed we have seen with F

AN

that a new prism could

with didactic added value could be implemented with

very little treatment (threshold values definition) be-

yond the grouping of two existing prisms. Careful

analysis and specification of implementation conse-

quences of the properties of prisms might constitute a

viable path toward end-user programming functional-

ities (Nardi, 1993) through the creation of compound

prisms.

REFERENCES

Antoniadis, G.,

´

Echinard, S., Kraif, O., Lebarb

´

e, T.,

Loiseau, M., & Ponton, C. (2004). NLP-based script-

ing for CALL activities. In Lemnitzer, E. H. L., edi-

tor, COLING 2004 eLearning for Computational Lin-

guistics and Computational Linguistics for eLearn-

ing, pages 18–25, Gen

`

eve. COLING. Available from:

http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00190373/fr/.

Antoniadis, G.,

´

Echinard, S., Kraif, O., Lebarb

´

e, T., &

Ponton, C. (2005). Mod

´

elisation de l’int

´

egration de

ressources TAL pour l’apprentissage des langues :

la plateforme MIRTO. ALSIC, 8(Num

´

ero sp

´

ecial

TALAL):65–79. Available from: http://alsic.u-

strasbg.fr/v08/antoniadis/alsic v08 04-rec4.htm.

Balatsoukas, P., Morris, A., & O’Brien, A. (2008). Learn-

ing objects update: Review and critical approach to

content aggregation. Journal of Educational Tech-

nology & Society, 11(2):119–130. Available from:

http://www.ifets.info/journals/11 2/11.pdf.

Bertrand, A., Cellier, J.-M., & Giroux, L. (1996). Ex-

pertise and strategies for the identification of the

main ideas in document indexing. Applied Cogni-

tive Psychology, 10(5):419–433. Available from:

http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/21437/

abstract.

edna, edna resources - metadata application

profile [online]. (2006). Available from:

http://www.edna.edu.au/edna/webdav/site/myjahiasite

/shared/edna resources metadata 1.0.pdf.

FACET AND PRISM BASED MODEL FOR PEDAGOGICAL INDEXATION OF TEXTS FOR LANGUAGE

LEARNING - The Consequences of the Notion of Pedagogical Context

421

GEM. Listing of GEM 2.0 top-level ele-

ments [online]. (2004). Available from:

http://www.thegateway.org/about/documentation/

metadataElements/index html.

Blanchard, A., Kraif, O., & Ponton, C. (2009). Mastering

noise and silence in learner answers processing: sim-

ple techniques for analysis and diagnosis. CALICO

Journal. Available from: http://tr.im/calicoabokcp.

Bourda, Y. (2002). Des objets p

´

edagogiques aux

dossiers p

´

edagogiques (via l’indexation). Docu-

ment num

´

erique, 6(1-2):115–128. Available from:

http://www.cairn.info/revue-document-numerique-

2002-1-page-115.htm.

Charlier,

´

E. (1989). Planifier un cours, c’est prendre des

d

´

ecisions. P

´

edagogies en d

´

eveloppement. S

´

erie 5,

Nouvelles pratiques de formation. De Boeck Univer-

sit

´

e, Bruxelles ; Paris.

IEEE (2002). Final 1484.12.1 LOM draft standard

document. Technical report, IEEE LTSC WG12.

Available from: http://ltsc.ieee.org/wg12/files/

LOM 1484 12 1 v1 Final Draft.pdf.

Loiseau, M. (2009).

´

Elaboration d’un mod

`

ele pour

une base de textes index

´

ee p

´

edagogiquement pour

l’enseignement des langues. PhD thesis, Uni-

versit

´

e Stendhal Grenoble 3. Available from:

http://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00440460/fr/.

Loiseau, M., Antoniadis, G., & Ponton, C. (2008).

Model for pedagogical indexation of texts for

language teaching. In Cordeiro, J., Shishkov,

B., Ranchordas, A., & Helfert, M., editors, IC-

SOFT (ISDM/ABF), volume ISDM/ABF, pages

212–217. INSTICC Press. Available from:

http://mathieu.loiseau.free.fr/bdtip/fichiers/articles/

icsoft-2008.pdf.

Nardi, B. A. (1993). A Small Matter of Programming: Per-

spectives On End User Computing. MIT Press, second

printing (1995) edition.

Pernin, J.-P. (2006). Normes et standards pour la concep-

tion, la production et l’exploitation des EIAH. In

Grandbastien, M. & Labat, J.-M., editors, Environ-

nements informatiques pour l’apprentissage humain,

pages 201–222. Herm

`

es et Lavoisier, Paris.

Recker, M. M. & Wiley, D. A. (2001). A non-

authoritative educational metadata ontology for

filtering and recommending learning objects. In-

teractive Learning Environments, 9(3):255–271.

Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/ lo-

gin.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=5848430&site

=ehost-live.

SCORM (2006). SCORM overview. Sp

´

ecification SCORM

2004 3rd Edition Content Aggregation Model Version

1.0, Advance Distributed Learning. Available from:

http://tr.im/scorm2004 3.

Yinger, R. J. (1978). A study of teacher planning: De-

scription and a model of preactive decision mak-

ing. East Lansing, MI. Michigan State Univer-

sity, Institute for Research on Teaching. Avail-

able from: http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/

detail?accno=ED152747.

APPENDIX: ACRONYMS

CALL Computer Assisted Language Learning

DCMI Dublin Core Metadata Initiative

edna Educational Network of Australia

EIAH Environnements Informatiques pour

l’Apprentissage Humain

GEM the Getaway to Educational Material

LOM Learning Object Metadata

MIRTO Multi-apprentissages Interactifs par des

Recherches sur des Textes et l’Oral

NLP Natural Language Processing

PC Pedagogical Context

SCORM Sharable Content Object Reference

Model

TAL Traitement Automatique des Langues

ICSOFT 2010 - 5th International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

422